Is Neck Pain Associated with Worse Health-related

Quality of Life 6 Months Later?

A Population-based Cohort StudyThis section was compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Spine J. 2015 (Apr 1); 15 (4): 675684 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Paul S. Nolet, DC, MS, MPHa, Pierre Cote, DC, PhD, Vicki L. Kristman, PhD, Mana Rezai, DC, MHS, Linda J. Carroll, PhD, J. David Cassidy, DC, PhD, DrMedSc

Department of Graduate Education and Research,

Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College,

6100 Leslie Street,

North York, Ontario, Canada. M2H 3J1.

BACKGROUND CONTEXT: Current evidence suggests that neck pain is negatively associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL). However, these studies are cross-sectional and do not inform the association between neck pain and future HRQoL.

PURPOSE: The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between increasing grades of neck pain severity and HRQoL 6 months later. In addition, this longitudinal study examines the crude association between the course of neck pain and HRQoL.

STUDY DESIGN: This is a population-based cohort study.

PATIENT SAMPLE: Eleven hundred randomly sampled Saskatchewan adults were included.

OUTCOME MEASURES: Outcome measures were the mental component summary (MCS) and physical component summary (PCS) of the Short-Form-36 (SF-36) questionnaire.

METHODS: We formed a cohort of 1,100 randomly sampled Saskatchewan adults in September 1995. We used the Chronic Pain Questionnaire to measure neck pain and its related disability. The SF-36 questionnaire was used to measure physical and mental HRQoL 6 months later. Multivariable linear regression was used to measure the association between graded neck pain and HRQoL while controlling for confounding. Analysis of variance and t tests were used to measure the crude association among four possible courses of neck pain and HRQoL at 6 months. The neck pain trajectories over 6 months were no or mild neck pain, improving neck pain, worsening neck pain, and persistent neck pain. Finally, analysis of variance was used to examine changes in baseline to 6-month PCS and MCS scores among the four neck pain trajectory groups.

RESULTS: The 6-month follow-up rate was 74.9%. We found an exposure-response relationship between neck pain and physical HRQoL after adjusting for age, education, arthritis, low back pain, and depressive symptomatology. Compared with participants without neck pain at baseline, those with mild (β=1.53, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.83, 0.24), intense (β=3.60, 95% CI=5.76, 1.44), or disabling (β=8.55, 95% CI=11.68, 5.42) neck pain had worse physical HRQoL 6 months later. We did not find an association between neck pain and mental HRQoL. A worsening course of neck pain and persistent neck pain were associated with worse physical HRQoL.

CONCLUSIONS: We found that neck pain was negatively associated with physical but not mental HRQoL. Our analysis suggests that neck pain may be a contributor of future poor physical HRQoL in the population. Raising awareness of the possible future impact of neck pain on physical HRQoL is important for health-care providers and policy makers with respect to the management of neck pain in populations.

KEYWORDS: Cohort study; Disability; Epidemiology; Health-related quality of life; Neck pain; Risk

Evidence & Methods Context

Prior research has demonstrated a negative association between chronic neck pain and Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL). The studys authors sought to examine this fact in a more robust fashion, using a longitudinal study involving a population of patients in Saskatchewan, Canada.

Contribution

The authors maintain that chronic neck pain is associated with worse physical HRQoL but not mental HRQoL. The authors postulate that chronic neck pain may be a contributor to poor physical HRQoL in the population.

Implications

As the authors correctly recognize, a degree of response bias may be impacting their findings. Furthermore, although prior work was largely cross-sectional, the follow-up in this analysis was limited to only six months. The temporality of the data may also be a concern and the fact that the study was conducted in Sakatchewan could also impair the generalizability of the results. Cultural, demographic and socioeconomic factors unique to the Canadian province may be qualitatively and quantitatively different from other populations in Canada and elsewhere. These factors could alter the extent to which neck pain is perceived, reported and considered to impact HRQoL.The Editors

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Over the past two decades, neck pain has become the fourth leading worldwide cause of years lived with disability [1]. Neck pain is common in the general population affecting 71% of adults during their lifetime [2, 3]. The 12-month prevalence of neck pain in adults varies from 30% to 50% [3]. Neck pain is commonly associated with activity limitations and disability [36]. The prevalence of neck pain peaks in middle-aged groups during the most productive years of a persons life. The annual incidence of neck pain in the general population varies depending on the definition of neck pain used. In Saskatchewan, Canada, neck pain had an annual incidence of 146 per 1,000 subjects. In South Manchester, UK, the reported annual neck pain incidence was 179 per 1,000 subjects [3]. Neck pain has a chronic recurrent course with more than one-third of the population suffering from persistent neck pain annually [4].

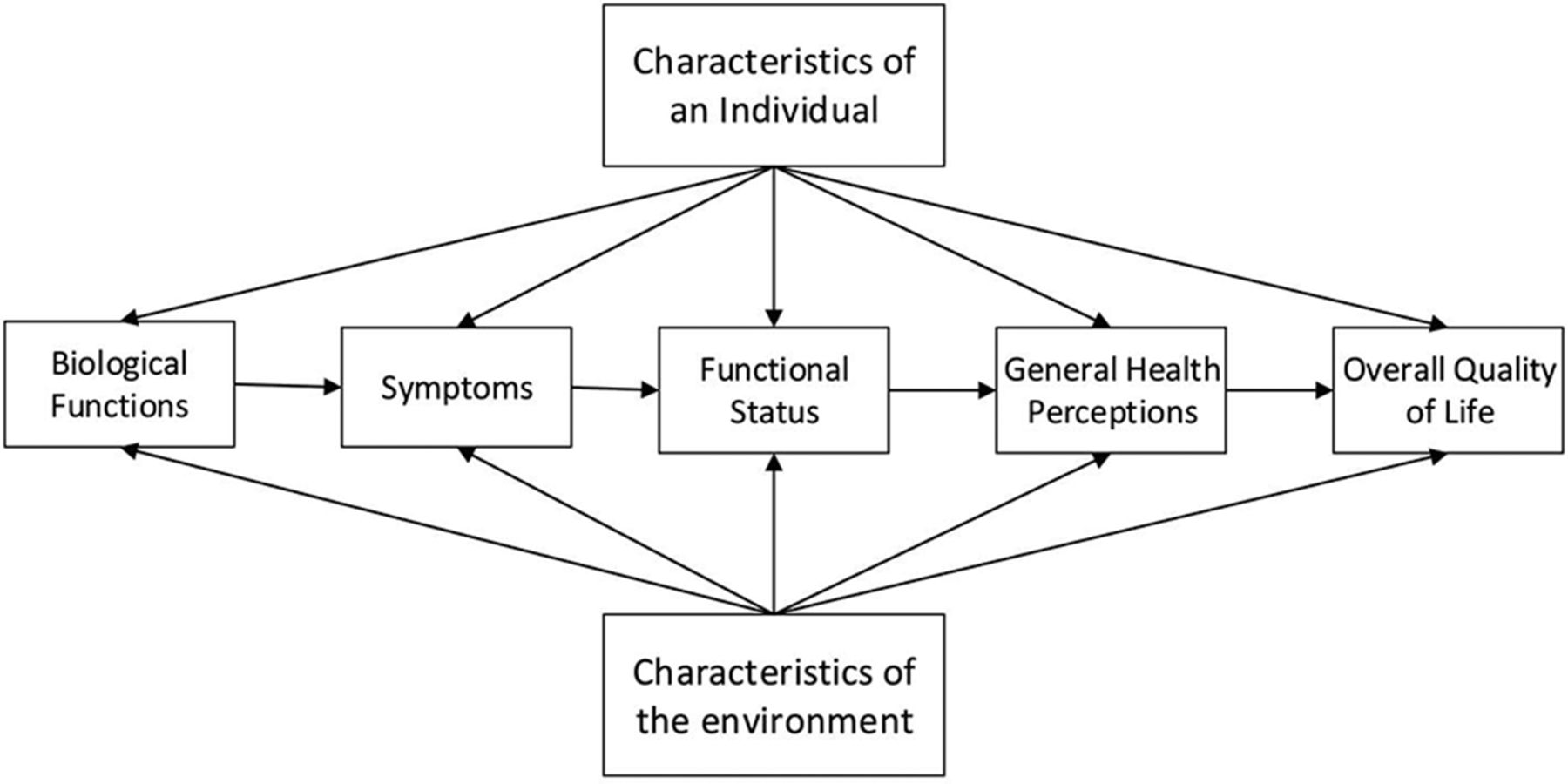

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a concept used in the health research to determine the impact of a disease on individuals and can help inform researchers, clinicians, and health policy makers. Health-related quality of life incorporates physical, mental, and social well-being rather than just defining health as the absence of disease [7]. Findings from a cross-sectional analysis of the Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey suggest that neck pain was weakly associated with worse physical HRQoL and not associated with mental HRQoL [8]. However, it remains unclear whether neck pain is a risk factor or an outcome of poor HRQoL. To our knowledge, only one study has reported that incident musculoskeletal disorders may have a negative effect on future physical HRQoL [9]. However, this association has not been examined prospectively in individuals with neck pain. The primary goal of our study was to determine whether neck pain is associated with worse HRQoL at follow-up in a general population cohort of adults from Saskatchewan. In addition, the crude association between the course of neck pain and the change in HRQoL between baseline and 6 months was examined.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to measure the association between neck pain and future HRQoL. Our results suggest that neck pain is associated with physical HRQoL and that the association follows a negative gradient from no neck pain to intense disabling neck pain. Controlling for baseline PCS HRQoL reduced this association. These results add to the findings of a previously published cross-sectional study from the Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey and confirm the presence of an association between neck pain and physical HRQoL [8]. The magnitude of the negative association between neck pain and physical HRQoL is larger in the cohort than previously reported in the cross-sectional analysis. This is likely because of the prevalence-incidence bias present in the cross-sectional analysis. Furthermore, the cross-sectional analysis reported comorbid conditions as potential confounders [8]. In our prospective cohort, musculoskeletal comorbidities and depression were the most important confounders of the association between graded neck pain and future physical HRQoL.

Our analysis supports the findings by Roux et al. [9] who found that incident musculoskeletal disorders were associated with reduced physical HRQoL compared with ageand sex-matched controls. Most importantly, our final model shows a clinically significant relationship between graded neck pain and physical HRQoL at 6 months. The difference in PCS scores from having no neck pain to severe neck pain (grades IIIIV) is of similar magnitude to substantial clinically important differences for both neck and arm pain after surgery [24] and arthritis after treatment [33].

Although there was a substantial crude relationship between neck pain severity and mental HRQoL, we did not find an association after adjusting for digestive problems, headaches, low back pain, and depressive symptomatology. This is in contrast with the findings of Roux et al. [9] of a weak association with mental HRQoL, although they did not adjust for depression. In our final model, depressive symptomatology was a substantial confounder, that is, it explained much of the association between crude neck pain severity and mental HRQoL. However, it should be noted that there is some reason to believe that depressive symptomatology may be a mediator rather than a confounder of the neck pain and/or mental HRQoL association. Depressive symptomatology has been shown to have a bidirectional relationship with neck pain [34, 35]. Thus, to the extent that depressive symptomatology is a risk factor for onset of neck pain, it could be considered as a confounding variable, as it was in the current analysis. However, there is also a strong theoretical and empirical knowledge base that depression is a consequence of pain [34, 36].

Thus, an alternative view would be that, rather than being a confounder of the neck pain and/or HRQoL association, depressive symptomatology actually serves as a mediator of that association. With depressive symptomatology as a mediator, the effect of neck pain severity on mental HRQoL would be through neck pains effect on depression. If this is the case, and depressive symptomatology is actually on the causal pathway between neck pain and HRQoL, adjusting for depression would have introduced rather than reduced bias, thus masking a true association [37]. Because of the theoretical and empirical justifications for both views (depressive symptomatology as a confounder or as a mediator), we chose the more conservative analysis strategy of adjusting for confounding, thus opting to err on the side of underestimating the association. In reality, depressive symptomatology is likely to be a confounder and a mediator. Therefore, the true impact of neck pain on mental HRQoL likely lies between our crude and adjusted estimates.

Controlling for baseline PCS in the final PCS model reduced the association with neck pain grade by improving PCS scores by 5.39 points in grades III to IV neck pain and 1.73 points in Grade II neck pain. In the PCS final model, adjusting for baseline differences in PCS may have led to overadjustment because of baseline PCS being on the causal pathway between graded neck pain and 6-month PCS [37]. Baseline PCS may mediate the association between baseline graded neck pain and 6-month PCS based on the measures used. Baseline graded neck pain was measured in the CPQ by asking seven questions; six of the questions asked about neck pain in the last 6 months. In the SF-36 PCS, questions relate to HRQoL at present and over the previous 4 weeks. If baseline PCS is a mediator, then it should not be adjusted for confounding influences. On the other hand, not controlling for baseline differences in PCS may cause us to overestimate our results if there is little mediation of the association. The true association likely lies somewhere between the final model including baseline PCS and the final model without baseline PCS.

Neck pain was the independent variable used in the multiple linear regression models of this study and includes everyone answering the baseline CPQ question on neck pain. Because we did not start with a population at risk of developing neck pain (incidence study), it was important to look at the course or trajectories of neck pain between the baseline and the 6-month survey. There was a crude association between the neck pain trajectories and both PCS and MCS scores at 6 months. PCS and/or MCS scores at baseline also predicted the course of neck pain in crude analyses. It is possible that HRQoL could be both a mediator and confounder of this association. Neck pain trajectories were also examined for changes in PCS and MCS scores over the 6 months of the study. The neck pain trajectory with persistent troublesome neck pain and the trajectory with worsening neck pain had worsening PCS change scores over the 6 months of the study (4.3 and 6.8 points, respectively). No changes in PCS scores were seen in the neck pain trajectory that improved over 6 months. It is possible that PCS HRQoL gets worse with the onset of neck pain and continues to get worse in subjects with ongoing persistent neck pain. Once neck pain improves, it may take a longer period of time to see improvements in physical HRQoL.

Our study has limitations. First, 55% of the invited study population participated in the survey. Therefore, it is possible that our results were influenced by selection bias. However, we are confident that our exposure was representative of the distribution in the study population [2]. Moreover, a previous analysis by Rezai et al. [8] suggests that missing baseline data did not lead to bias in this dataset. Second, it is possible that selection bias was introduced through loss to follow-up. Nonresponders to the 6-month follow-up survey questionnaire were younger, less educated, and had lower income than responders. However, their baseline PCS and MCS scores were similar, which suggest that attrition was not because of baseline HRQoL. Third, the SF-36 is known to be more responsive to lumbar spine and lower extremity function than to the upper extremity and the cervical spine function [7]. Therefore, the instrument may not have fully captured the impact of neck pain on physical HRQoL. Finally, our analysis of the MCS scores may have been overadjusted for depressive symptomatology, which may be both a mediator and a confounder of the association between neck pain and HRQoL [34]. As mentioned previously, viewing depressive symptomatology as a confounder of the association between neck pain and HRQoL may have led to an underestimation of the true effect.

Our results indicate that neck pain can affect the future physical health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of individuals. This impact was worse in individuals with worsening or persistent neck pain. These results emphasize the importance for health-care providers and policy makers to manage neck pain with early effective interventions to minimize the long-term impact on physical HRQoL. Future research needs to examine the course of neck pain on HRQoL while controlling for the confounding effects of socioeconomic, lifestyle, and comorbidities. Further research is also needed to examine the mediating and confounding effects of depression on the association between neck pain and mental HRQoL.

References:

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, et al.:

Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) for 1160 Sequelae of 289 Diseases and Injuries 1990-2010:

A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

Lancet. 2012 (Dec 15); 380 (9859): 21632196Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L.

The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey.

The Prevalence of Neck Pain and Related Disability in Saskatchewan Adults

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 (Aug 1); 23 (15): 16891698Hogg-Johnson, S., van der Velde, G., Carroll, L. J. et al (2008).

The Burden and Determinants of Neck Pain in the General Population:

Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 20002010 Task Force

on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S3951Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Kristman V.

The annual incidence and course of neck pain in the general population:

a population-based cohort study.

Pain 2004;112:26773.Cote P, van der Velde G, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Holm LW, et al.

The Burden and Determinants of Neck Pain in Workers: Results of the Bone and Joint Decade

20002010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S60-74Cote P, Kristman V, Vidmar M, Van Eerd D, Hogg-Johnson S, Beaton D, et al.

The prevalence and incidence of work absenteeism involving neck pain, a cohort

of Ontario lost-time claimants.

Spine 2008;33(4 Suppl):S1928.Carlesso LC, Walton DM, MacDermid JC.

Reflecting on whiplash associated disorders through a QoL lens: an option to advance

practice and research.

Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:11319.Rezai M, Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ.

The association between prevalent neck pain and health-related quality of life:

a crosssectional analysis.

Eur Spine J 2009;18:37181.Roux CH, Guillemin F, Boini S, Longuetaud F, Arnault N, Hercberg S, et al.

Impact of musculoskeletal disorders on quality of life: an inception cohort study.

Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:60611.Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ.

Is a lifetime history of neck injury in a traffic collision associated with

prevalent neck pain, headache and depressive symptomatology?

Accid Anal Prev 2000;32:1519.Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L.

The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey.

The Prevalence of Neck Pain and Related Disability in Saskatchewan Adults

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 (Aug 1); 23 (15): 16891698von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF.

Grading the severity of chronic pain.

Pain 1992;50:13349.Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, Le Resche L.

Graded chronic pain status: an epidemiologic evaluation.

Pain 1992;40:27991.Guzman J, Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, et al.

Clinical Practice Implications of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010

Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders:

From Concepts and Findings to Recommendations

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S199S212Nolet PS, Cτtι P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ.

The Association Between a Lifetime History of a Neck Injury in a Motor Vehicle Collision

and Future Neck Pain: A Population-based Cohort Study

European Spine Journal 2010 (Jun); 19 (6): 972981Nolet PS, Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ.

The association between a lifetime history of a work-related neck injury and

future neck pain: a population based cohort study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2011;34: 34855.Elliott AM, Smith BH, Smith WC, Chambers WA.

Changes in chronic pain severity over time: the Chronic Pain Grade as a valid measure.

Pain 2000;88:3038.Smith BH, Penny KI, Purves AM, Munro C, Wilson B, Grimshaw J, et al.

The chronic pain grade questionnaire: validation and reliability in postal research.

Pain 1997;71:1417.Ware JE Jr, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B.

SF-36 health survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide.

Boston, MA: The Health Institute,

New England Medical Center, 1993.Brazier J, Harper R, Jones SN.

Validating the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire:

New Outcome Measure for Primary Care

British Medical Journal 1992 (Jul 18); 305 (6846): 160-164Beaton DC, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C.

Evaluating changes in health status: reliability and responsiveness of five generic

health status measures in workers with musculoskeletal disorders.

J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:7993.Ware JE, Gandek B.

Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the International Quality of Life

Assessment (IQOLA) Project.

J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:90312.Ware JE.

SF-36 health survey update.

Spine 2000;25:31309.Carreon LY, Glassman SD, Campbell MJ, Anderson PA.

Neck disability index, short form-36 physical component summary, and pain scales

for neck and arm pain: the minimum clinically important difference and substantial

clinical benefit after cervical spine fusion.

Spine J 2010;10:46974.Geisser ME, Roth RS, Robinson ME.

Assessing depression among persons with chronic pain using the Center for

Epidemiological StudiesDepression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory:

a comparative analysis.

Clin J Pain 1997;13:16370.Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Tilburg W.

Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D):

results from a community-based sample of older participants in the Netherlands.

Psychol Med 1997;27:2315.Radloff LS. The

CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population.

Appl Psychol Meas 1997;1:385401.Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, Myers JK.

Screening for depression in a community sample.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39: 11952000.Devins GM, Orme CM, Costello CG, Minik YM, Frizzell B, Stam HJ, et al.

Measuring depressive symptoms in illness populations: psychiatric properties of

the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale.

Psychol Health 1988;2:13956.Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ.

Factorial and discriminant validity of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies

Depression (CES-D) Scale.

J Clin Psychol 1986;42:2833.Rothman KJ.

Epidemiology, an introduction.

New York: Oxford University Press, 2002:1937.IBM SPSS statistics, version 20.

New York: IBM Inc., 2011.Kosinski M, Zhao SZ, Dedhiya S, Osterhaus JT, Ware JE.

Determining minimally important changes in generic and disease-specific health-related

quality of life questionnaires in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis.

Arthritis Rheum 2000;47:147888.Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Cote P.

Factors associated with the onset of an episode of depressive symptoms in the general population.

J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:6518.Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Cote P.

Depression as a risk factor for onset of an episode of troublesome neck and low back pain.

Pain 2004;107: 1349.Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Cote P.

Frequency, timing, and course of depressive symptomatology after whiplash.

Spine 2006;31: ESS16.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW.

Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies.

Epidemiology 2009;20:48895.

Return to CHRONIC NECK PAIN

Since 10-15-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |