Enhancing Comprehensive Primary Care by Integrating

Chiropractic Led Musculoskeletal Care Into

Interprofessional Teams Through Supporting

Education, Competency Attainment, and

Optimizing IntegrationThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Healthc Manage Forum 2024 (Sep); 37 (1_suppl): 55S–61S ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Silvano Mior, DC, FCCS, PhD • Diana De Carvalho, DC, PhD • Jairus Quesnele, DC, FCCS, APP

Sheilah Hogg-Johnson, PhD • Pegah Rahbar, BSc, DC • Megan Logeman, BSc, PMP

Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions are the leading cause of disability, resulting in up to 40% of visits to family physicians. Current primary care workforce shortages in Canada require other providers to maximize scopes of practice. Few MSK providers have been trained in team-based primary care settings. Study objectives included: (1) educating participating primary care teams through synchronous education, (2) educating Canadian primary care providers through asynchronous education, and (3) integrating chiropractors into primary care teams, whilst evaluating team MSK care knowledge/attitudes and integration experience. Results indicated improvements in collaborative competency, improved understanding and attitudes to chiropractic, and the importance of providing MSK care within funded primary care. Teams employed unique approaches to integrating chiropractors and indicated high demand for their services by patients and providers. Provision of MSK care without economic barrier is desirable and highly valued by teams. Chiropractors are well suited to participate in funded primary care teams in Canada.

Keywords:

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions are the leading cause of disability in Canada and a significant burden to people, health systems, and economies. [1] In most Canadian provinces, public funding for MSK care is limited, posing a significant barrier to patient access. In the United States, MSK complaints are the most common reason for primary care appointments, accounting for approximately 40% of encounters, [2] highlighting the importance of strengthening MSK expertise in primary care to impact patient outcomes. One solution is to provide integrated MSK care (embedding MSK care providers such as chiropractors and physiotherapists) as part of comprehensive primary care.

Currently, few MSK health providers have been formally trained in Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC), limiting integration and optimization of team-based patient-centred care. Interprofessional Education (IPE) supports the development of a competent health workforce and helps mitigate the current fragmentation of care in health service delivery. [3] To address this gap, a three-phased project was conducted with the aim of evaluating the feasibility of educating primary care and rehabilitation clinicians on MSK burden in Canada, the essentials of team-based care, interprofessional competencies, and the role of a chiropractor (Phases 1 and 2) and then observing the process of integrating a chiropractor into primary care team settings across Canada (Phase 3).

In Phase 1, the study evaluated the knowledge of interprofessional competencies and attitudes toward chiropractors from five primary care teams who engaged in standardized synchronous educational modules. In Phase 2, asynchronous web-based education was offered to primary care providers interested in MSK health across Canada. Phase 3 involved the embedding of chiropractors into four of the primary care teams and evaluated the teams’ experience with this integration.

This research project hypothesized that providing education focused on team-based care, interprofessional competencies, and the role of a chiropractor on primary care teams, would facilitate successful integration of a chiropractor into these teams, resulting in a collaborative and functional team dynamic that meets patient expectations for seamless care of their MSK conditions.

Methodology

In Phase 1, a pre-post outcome design was used to quantitatively and qualitatively evaluate participant changes to an educational intervention. In Phase 2, participants completed post-module questionnaires. In Phase 3, a mixed methods exploratory design was applied to identify unique and common factors that occurred while integrating chiropractors into the primary care teams.

Table 1 In Phase 1 (Synchronous Education), five primary care teams across Canada including their recruited study chiropractor participated in a one-hour educational webinar. The inclusion criteria required a minimum of three disciplines, including the chiropractor, willing to provide patient care at the site who consented to participating in the educational phase to enter the integration phase. The objective of the webinar was to describe the burden of MSK conditions, describe the interprofessional competencies for effective team-based care, and develop an approach to a funded model of MSK integrated patient care. A summary of synchronous education intervention participation is included in Table 1.

Phase 2 (Asynchronous Web-Based Learning) included a one-hour asynchronous module with similar content and method of post course evaluation as in Phase 1. Individual practitioner participants were recruited through organizations’ newsletters and emails. The objective of this phase was to collect richer data on the impact of the education on interprofessional competencies and attitudes toward chiropractic to inform future teaching methodologies.

Table 2

see p. 3Of the five primary care teams participating in the study, funding only permitted four to proceed to the integration of chiropractic care in Phase 3. Each team completed logs and evaluation forms to document their process. A comprehensive description of the study phases is included in Table 2.

Data collectionPhase 1: Synchronous education – quantitative evaluation

Participants completed pre- and post-education questionnaires evaluating their comfort level in collaborating in practice (Health Professional Collaborative Competency Perception Scale (HPCCPS)), [4] their knowledge and attitudes about chiropractic (Chiropractic Attitudes Questionnaire (CAQ)), and evidence-based management of low back pain (LBP Guidelines Adherence Case Study). Data were collected through Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com) and deidentified. Pre- and post-HPCCPS scores were compared by describing mean and standard deviation and comparing means using independent sample t tests. The questionnaire assessing attitudes and perceptions to chiropractic, adapted from previous work, [5] was administered to participants and descriptively analysed as was the four-item questionnaire evaluating LBP guideline adherence. These analyses were generated using SAS software v9.4 (https://www.sas.com/).

Phase 1: Synchronous education – qualitative evaluation

Qualitative data were obtained in two formats, from open ended questions included in the surveys and from focus groups. We used focus groups to gather data to better understand survey responses and to further explore participants’ attitudes and perspectives of IPC. Focus groups are useful for exploring knowledge and experiences, as they examine not only what people think but how and why they think that way. [6] The moderator’s guide included semi structured and open questions, partly informed by an IPC Competency Framework previously developed by and implemented at Unity Health Toronto.

Phase 2: Asynchronous education

A learning management platform was created to develop five modules using synchronous webinar content, recorded speakers, web site content, and links. The learning platform was embedded on a newly developed web site, TeamMSK.ca, used to inform potential participants about the project. Consenting study participants accessing the modules were asked to complete the same evaluation tools as the synchronous education participants (HPCCPS, CAQ, and LBP Guidelines Adherence Case Study). Quantitative data for the asynchronous modules were collected through Survey Monkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com) and deidentified. Post-module questionnaires were analysed descriptively.

Phase 3: Integration

This phase integrated chiropractors into one of four primary care team sites and evaluated their integration as a new or enhanced MSK provider. Following the integration period, teams were asked to repeat the questionnaires and participate in key informant interviews or focus groups. Qualitative methods were used to explore participants’ experiences, attitudes, and perspectives on the integration of chiropractors in their settings, as well as to gain a deeper understanding of the outcomes of the integration process and the unique models developed at each site.

Results

Phase 1: Education – surveys

Five primary care teams from rural and urban sites across Canada participated in the synchronous education. Pre-module questionnaires were completed between October and November 2023 and involved 5-13 participants at each site (Table 1). The HPCCPS survey was completed by 29 participants from the five primary care teams. Twenty-four completed the post-module survey. Across the eight HPCCPS domains, there was evidence of improvement in self-perception of collaborative competency following the education session.Attitudes to chiropractic

Twenty-eight completed the scale before and 22 after the education module. Again, there was evidence of increased understanding and a positive attitude toward chiropractic post-module.

LBP guidelines case study

Twenty-four completed the pre module case and 22 completed it post-module. Results revealed improvement in the number of correct answers given by participants on the post-module test.

Phase 1: Education – focus groups

Table 3

see p. 4The first focus group was held virtually in February 2024, involving six participants: two family physicians and four chiropractors. During the early stages of project implementation, the emergent themes revolved around the education session, site specific challenges, pre-study questionnaires, and benefits of project (Table 3). Participants felt the pre-study questionnaires seemed disconnected with the content of the educational session and suggested the questions may not be relevant to all their team providers and staff (Table 3: III). The education session provided important material, but many participants indicated they already had adequate knowledge of key principles (Table 3: Ia). Participants felt the guideline specific information was helpful to support the inclusion of multiple team members and define their roles (Table 3: Ib and c). Participants felt the educational content was too theoretical, preferring practical examples of how to integrate (Table 3: Ie). Nevertheless, the content provided a “launch pad” for their team meetings to begin addressing implementation processes for their team (Table 3: Id). Participants described different experiences in approaching project implementation, related to site and organization (Table 3: II). Participants agreed the project would benefit patients, particularly those who would not otherwise access musculoskeletal care because of costs.

Phase 2: Asynchronous web-based education

The asynchronous course enrolled 361 healthcare professionals with representation from all Canadian provinces and territories with 81% completing the research evaluation survey. Individuals from three healthcare disciplines completed the post-module surveys (HPCCPS and LBP guidelines questions) (total N = 293) with almost all being (291) chiropractors. Collaborative care competency was self-rated by participants as “very high” (average over 80%), with majority of respondents answering the LBP guideline questions correctly. Final, detailed analysis of this dataset is currently underway.

Phase 3: Integration

Four primary care teams participated in Phase 3. Three teams had no previous experience with chiropractors integrated in their teams. One team had an embedded chiropractor but felt that this could be significantly enhanced with additional evidence to support expanded provincial funding. Participating teams were from different provinces (British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Newfoundland and Labrador) and in different clinical settings (academic affiliated clinic, inner city community clinic, family health team, and a small hospital clinic) with different government funding models for primary care.

Data collected included review of site logs (in process), focus group, and key informant results and questionnaire results. Chiropractors collected data regarding numbers of patients attending for care. Referrals came from physicians, nurse practitioners, medical residents and clerks, and by patient self-referral. During the study, approximately 600 patient visits were provided. Feedback from the chiropractors indicated that referrals exceeded their capacity to accommodate during their allotted (funded) clinical time. Within the first 2 months, one chiropractor reported they were unable to accommodate new patient referrals for the next 3 months. Similar reports were also provided by chiropractors at the other sites where they were a new member to the team.

At the end of Phase 3, focus group and key informant data reinforced earlier findings, particularly related to the educational sessions (Table 3: B1a-c); however, sites interviewed used the sessions as background to conduct their meetings and address site specific issues (Table 3: B1d, e). Sites faced different challenges, addressed partially or fully by meetings and/or modifying processes (Table 3: BII). Team-based benefits of integration varied; however, positive patient outcomes and demand for services were noted across all sites. (Table 2: BIV).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to educate primary care and rehabilitation providers on MSK burden in Canada, the essentials of team-based care, interprofessional competencies, and the role of a chiropractor (Phases 1 and 2), and then assess the process of integrating a chiropractor into primary care team settings (Phase 3). The study results provide insight into the educational gaps in interprofessional competencies and the benefits of flexible education formats to inform competencies that enhance team-based care. Providing an education foundation prior to clinical integration appears helpful but should be tailored to the specific clinic needs and knowledge of participating providers.

Results from pre-/post-module surveys suggest the IP education improved collaborative competency, understanding and attitudes to chiropractic care, and the importance of addressing musculoskeletal complaints in funded primary care. This type of improvement in collaborative competency was similarly noted in earlier IPE delivery. [7] Evidence from the focus group sessions indicated that much of the educational content may not have been new, but that revisiting content was valuable and set the stage for collaborative discussion and team planning. Participant feedback suggested familiarity with the theoretical basis for integration and collaboration, but a need for further information and training on the practical components required for implementation. This may be even more relevant given that there appeared to be variation in the specific/local organization and system factors existing at different sites contributing to different challenges experienced by the individual groups. This may be an important aspect to consider for future integration programs.

Participants acknowledged the need for MSK expertise within primary care as highly important. Teams expressed that the educational component provided an opportunity for teams to establish their roles and function by learning together from those practicing in existing interprofessional teams. Teams were eager to hear about previous successful models of chiropractic integration to help alleviate this challenge, such as the integration of chiropractors into St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, [8] and chiropractors integrated into Ontario family health teams. [9] As teams uniquely developed their models of care, they were able to offer access to patients through study funding and realize the added value of chiropractors to patient treatment options. Team members and patients expressed the desire to be able to continue to provide and access chiropractic care without economic barrier after the study and were interested in collaboratively seeking sustainable funding opportunities. Clearly, the quantitative and qualitative results suggest that patients benefited from timely access to MSK care, with many team members acknowledging the barriers of cost would otherwise preclude care for many patients. Further, team-based care, that maximizes the scope of all, is the most efficient way to manage MSK cases in primary care.

Despite the sites being located in different provinces, clinical contexts and funding models, each of the teams were able to successfully integrate the chiropractors, using strategies and adapting approaches unique to their context and clinical setting. These results are similar to previous studies [8, 9] and indicate the potential for and feasibility of MSK provider integration across various primary care contexts (scalability) in Canada.

Reflecting on this innovative project (supported by the Team Primary Care initiative), the researchers realized many benefits of this collaboration including access to multiple team-based care resources and a sense of belonging to a greater and broader initiative. The potential partnerships forged with the Team Primary Care leaders will help to define and support future projects.

Limitations

The study length was compressed to 9 months due to time required for recruitment, enrollment, designated educational sessions, and multiple institutional REB submissions. At the time of the invited journal submission, the final round of data had been only recently collected and, while cursory review indicated the same trend in findings, the final data had not yet been fully analyzed. The study sample was limited to five educational sites and four integration sites due to funding limitations despite significant interest demonstrated in many provinces. The scope and timeline also limited this project to focus on chiropractic integration and did not include physiotherapists for this preliminary study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study results indicate that integrating chiropractors as MSK providers within primary care teams across different settings and provincial contexts is feasible and desirable by both patients and provider team members. Integration benefits from provision of team education on optimizing team-based care, understanding interprofessional competencies, and learning from existing similar models of care. The results of this study may be helpful for other teams seeking to model MSK provider integration into funded primary care. The remaining challenge is the lack of prioritization of, and funding for, MSK healthcare within primary care. Thus, a call and action for this is needed amongst policy-makers in Canada.

Acknowledgements

As well as grants from the Canadian Chiropractic Association and the British Columbia Chiropractic Association, in-kind services were provided by the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College and the

Ethical approval

Research Ethics Board approvals were received from Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (REB 2307B01), University of Toronto (REB 45182), Health Research Ethics Board of Newfoundland and Labrador (HREB 2023.161), Laurentian University/NOSM University (REB 6021454), and University of Manitoba. Participants provided written and/or verbal consent to participate in the study.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Team Primary Care was supported by Employment and Social Development Canada through a grant to the Foundation for Advancing Family Medicine, co-lead by the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Canadian Health Workforce Network.

References

Liu S, Wang B, Fan S, Wang Y, Zhan Y, Ye D.

Global burden of musculoskeletal disorders and attributable factors

in 204 countries and territories: a secondary analysis of

the global burden of disease 2019 study.

BMJ Open. 2022;12(6):e062183.Wu V, Goto K, Carek S, et al.

Family medicine musculoskeletal medicine education: a CERA study.

Fam Med. 2022;54(5):369-375.World Health Organization.

Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice

WHO/HRH/HPN/10.3.Kopansky-Giles D.

Development and Evaluation of the Health Professional

Collaborative Competency Perception Scale (HPCCPS).

[Unpublished Masters thesis].

Bournemouth, UK: University of Bournemouth; 2010.Busse JW, Pallapothu S, Vinh B, et al.

Attitudes Towards Chiropractic:

A Repeated Cross-sectional Survey of Canadian Family Physicians

BMC Family Practice 2021 (Sep 15); 22 (1): 188Doody O, Slevin E, Taggart L.

Preparing for and conducting focus groups in nursing research: part 2.

Br J Nurs. 2013;22(3):170-173.Peranson J, Weis CA, Slater M, Plener J, Kopansky-Giles D.

An interprofessional approach to collaborative management of

low-back pain in primary care: a scholarly analysis of a

successful educational module for prelicensure learners.

J Chiropr Educ. 2024;38(1):30-37.Kopansky-Giles D, Vernon H, Boon H, et al.

Inclusion of a CAM Therapy (Chiropractic Care) for the

Management of Musculoskeletal Pain in an Integrative,

Inner City, Hospital-based Primary Care Setting

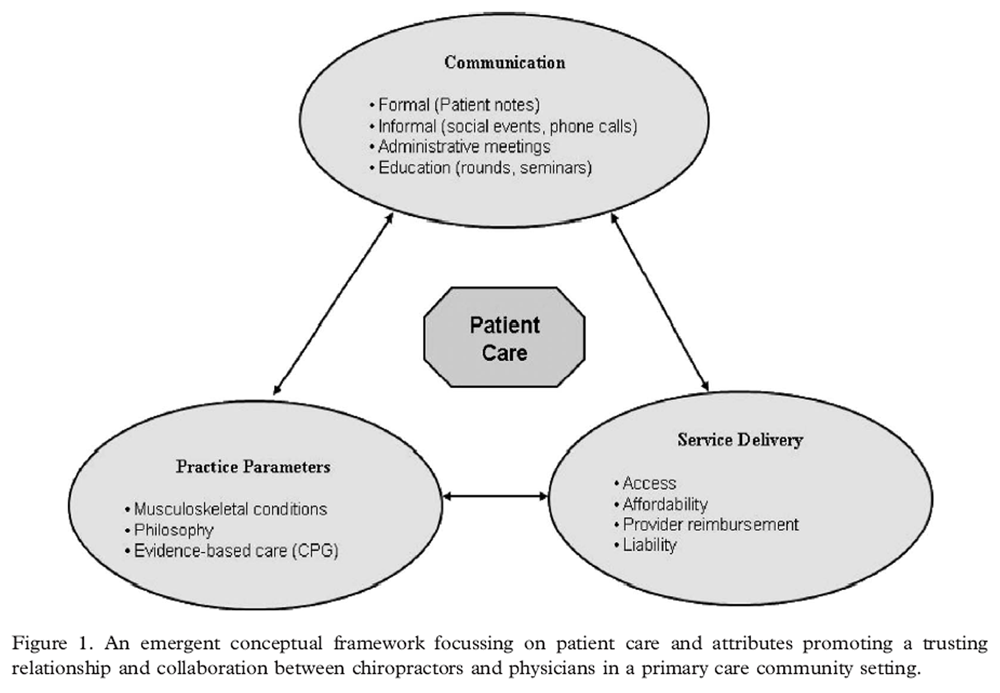

J Alternative Medicine Research 2010 (Dec); 2 (1) 61–74Mior S, Barnsley J, Boon H, Ashbury FD, Haig R.

Designing a Framework for the Delivery of Collaborative

Musculoskeletal Care Involving Chiropractors and

Physicians in Community-based Primary Care

J Interprof Care. 2010 (Nov); 24 (6): 678–689

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Since 9-03-2024

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |