Systematic Review and Synthesis of Mechanism-based

Classification Systems for Pain Experienced

in the Musculoskeletal SystemThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Clinical J Pain 2020 (Oct); 36 (10): 793–812 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Muath A. Shraim, BPhty (Hons), Hugo Massé-Alarie, PhD, Leanne M. Hall, PhD, and Paul W. Hodges, PhD

NHMRC Centre of Clinical Research Excellence in Spinal Pain,

Injury & Health, School of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences,

The University of Queensland,

St Lucia, QLD, Australia.

FROM: J Pain Res. 2021Objectives: Improvements in pain management might be achieved by matching treatment to underlying mechanisms for pain persistence. Many authors argue for a mechanism-based classification of pain, but the field is challenged by the wide variation in the proposed terminology, definitions, and typical characteristics.

This study aimed to(1) systematically review mechanism-based classifications of pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system;

(2) synthesize and thematically analyze classifications, using the International Association for the Study of Pain categories of nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic as an initial foundation; and

(3) identify convergence and divergence between categories, terminology, and descriptions of each mechanism-based pain classification.Materials and methods: Databases were searched for papers that discussed a mechanism-based classification of pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system. Terminology, definitions, underlying neurobiology/pathophysiology, aggravating/easing factors/response to treatment, and pain characteristics were extracted and synthesized on the basis of thematic analysis.

Results: From 224 papers, 174 terms referred to pain mechanisms categories. Data synthesis agreed with the broad classification on the basis of ongoing nociceptive input, neuropathic mechanisms, and nociplastic mechanisms (eg, central sensitization). "Mixed," "other," and the disputed categories of "sympathetic" and "psychogenic" pain were also identified. Thematic analysis revealed convergence and divergence of opinion on the definitions, underlying neurobiology, and characteristics.

Discussion: Some pain categories were defined consistently, and despite the extensive efforts to develop global consensus on pain definitions, disagreement still exists on how each could be defined, subdivided, and their characteristic features that could aid differentiation. These data form a foundation for reaching consensus on classification.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

BACKGROUND

There is no doubt that pain is a major issue. Approximately 10% to 20% of individuals in Western societies experience persistent pain. [1–3] Despite substantial research and developments in management, pain outcomes have improved little. [4–6] An important consideration is that not all pain is the same, and there is growing discussion that pain outcomes might improve if the mechanisms underlying maintenance of pain were considered when tailoring interventions for individuals. [7–10] “Mechanisms” could reflect a vast group of processes within the body. For clarity, we define pain “mechanisms” as the general groupings of neurobiological processes involved in and dominating the pain experience. There is not yet agreement on how different pain mechanisms can be classified and discriminated. [8, 11] This is particularly problematic for pain associated with the musculoskeletal system, where definitive identification of underlying mechanisms for persistence of pain can be difficult because of limitations of diagnostic tests, [10, 11] lack of consensus on the possible mechanisms of pain, [11] and the interaction between biological, psychological, and social features. [12, 13] A first step toward the classification and discrimination of pain mechanisms in pain associated with the musculoskeletal system is to understand the diversity of current opinion.

It is well recognized that the experience of pain does not simply involve transmission of input via a pain pathway. [7, 13, 14] Instead, it involves an array of potential inputs and outputs, with the involvement of diverse biological systems and regions of the nervous system, that are influenced by many factors including emotions and cognitions. [7, 13, 14] Although activation of nociceptive neurons provides one input, particularly in an acute context, many other inputs and mechanisms can interplay to shape the pain experience, and these will differ between individuals. [15] The notion that different mechanisms might respond to different treatments is not new. [15–17] It has been broadly discussed that identification of mechanism and subsequent classification of patients to a pain mechanism category (PMC) may be based on the characteristics of their presentation. [18–21] On this basis, many different groupings have been proposed with a diversity of terminology and proposed features. [11, 15, 18]

Table 1 The expansive research on this issue has resulted in considerable confusion. First, different terminologies are used, [11, 15, 18] and it is often unclear which terms are interchangeable. For instance, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) suggests 3 main PMCs: nociceptive, neuropathic, and the recently proposed nociplastic mechanisms (Table 1). [22] Although the IASP has provided definitions for these 3 groups, multiple other classifications have been proposed that have used different terminology, different definitions, and a variety of presenting features. [23–26] Second, the understanding of underlying mechanisms continues to evolve and some early terminology and groupings that were included in early summaries of terminology appear to have become redundant and are not included in the most recent IASP terminology (eg, sympathetic pain [22]).

Third, some work has focused on specific conditions and developed unique language and interpretation rather than an overarching and generalizable conceptualization (eg, dystonic pain in Parkinson disease [27]). Fourth, because many aspects of the underlying mechanisms are difficult, if not impossible, to directly assess in vivo, [10, 28] validation of methods to differentiate categories has been limited. Fifth, some confusion with interpretation of outcomes is likely to have led to overidentification of some categories (eg, identification of features of sensitivity in some musculoskeletal conditions has been interpreted as evidence of neuropathic pain, [29, 30] when it might be explained by nociplastic mechanisms rather than nerve damage/dysfunction). Finally, mechanisms that underlie pain in an individual can change over time, and multiple mechanisms can occur simultaneously. [16, 31]

OBJECTIVES

This study aimed to(1) systematically review mechanism-based classifications that have been proposed to differentiate pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system;

(2) synthesize and thematically analyze proposed classifications, using the IASP categories of nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain as an initial foundation; and

(3) and identify convergence and divergence between categories, terminology, and descriptions of each mechanism-based pain classification as described by opinions presented in the literature, which could aid differentiation of mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

The literature describing mechanism-based pain classification for pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system was systematically reviewed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. [32] A protocol of this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42018115452). The review was undertaken by 4 reviewers with backgrounds in physiotherapy research and clinical practice (years of experience: M.A.S.—4; H.M.-A.—10; L.M.H.—13; and P.W.H.—28).

Search Strategy and Screening

As the primary objective was to document the breadth of systems used to classify pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system by mechanisms and the opinions on classifications presented in the literature, lenient eligibility criteria were used. Papers of any type were considered and there were no restrictions by publication date or by patient population other than the fact that the pain must be considered to be primarily experienced in the musculoskeletal system and not related to cancer.

The strategy to identify relevant papers included a search of (1) PubMed, EMBASE, and CINAHL databases, (2) reference lists of included papers and relevant previously published reviews, and (3) resources provided by the IASP. A comprehensive search was conducted on November 11, 2018 and updated on December 6, 2019 before the final analyses. A similar search strategy was used for all 3 databases, but was modified where necessary. Search strategies for all databases are presented in Supplemental Digital Content 1 (http://links.lww.com/CJP/A657).

Papers were included if they fulfilled the following criteria:(1) the paper describes a classification of pain, primarily experienced in the musculoskeletal system, on the basis of different underlying mechanisms (eg, physiological/ neurobiological processes),

(2) the classification system must acknowledge > 1 category or mechanism of pain,

(3) the classification system could be either complete (accounting for every possible presentation of pain) or partial (accounting for some but not all possible presentations of pain) within a single condition or multiple conditions,

(4) the paper must include a definition and/or characterization of at least 2 pain categories or mechanisms,

(5) the pain could have any time-course (eg, acute, chronic) and can be either clinical or experimental,

(6) human studies or reviews of pain mechanisms based on animal studies, or

(7) papers or abstracts in English.

Papers were excluded if they(1) described a classification system that was related to pain not primarily experienced in the musculoskeletal system (eg, visceral pain, vascular pain) or pain related to cancer or surgery,

(2) described a classification system that was not related to pain mechanisms (eg, differentiation of groups on the basis of treatment response without consideration of mechanisms; differentiation by disease mechanism rather than pain mechanism; and differentiation between separate clinical conditions, without explicit reference to pain mechanism such as back pain vs. fibromyalgia),

(3) were primary intervention studies (except interventions that include differentiation of pain on the basis of mechanism),

(4) were studies or reviews that refer to a mechanism-based system presented by other authors without provision of information in addition to that provided in the primary sources,

(5) were studies that simply translated questionnaires that aimed to differentiate pain into a second language, or

(6) were primary non-human animal studies.

Data Extraction

All titles and abstracts yielded by the search were screened for eligibility by 1 reviewer (M.A.S.). To control for potential bias, a second reviewer (H.M.-A.) screened a random sample of the papers (3% ~300 papers), and a comparison of included papers was used to test for agreement between the 2 reviewers. Any discrepancies were noted and discussed with a third reviewer (P.W.H.). Once all potential discrepancies were identified and there was minimal disagreement, 1 reviewer (M.A.S.) continued the screening process.

The full-text review and inclusion/exclusion of screened papers was undertaken by 1 reviewer (M.A.S.). The third reviewer (P.W.H.) evaluated a random selection of papers (~30 to 40 papers) to evaluate the accuracy of inclusion and discussed any papers that the first reviewer highlighted as uncertain for inclusion.

All data extraction was undertaken by 1 reviewer (M.A.S.). The third reviewer (P.W.H.) evaluated a random selection of papers (~30 to 40 papers) to evaluate the accuracy of data extraction and discussed any papers highlighted by the first reviewer as requiring clarification for data extraction.

A piloted form was used to extract the following data: participant group, paper type, or method used to derive the definition for the mechanism-based pain classification (eg, systematic review, expert consensus), the group or individuals who contributed to the development/proposal of the pain classification system (data included whether the papers involved a single or multiple authors, and whether a consensus approach was used), the primary purpose of the paper, the categories or mechanisms of pain (this was the terminology used by the authors if a title for the category was provided or keywords from the description if no title was provided), the definition/description of each category or mechanism of pain, and the presenting characteristics/ features of each category or mechanism of pain.

No paper was excluded on the basis of assessment of quality as the purpose of the review was to gain a comprehensive view of the mechanism-based classifications proposed to differentiate pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system. An adapted version of Critical Appraisal of Classification Systems [33] was used to document the comprehensiveness and utility of the proposed classification methods via assessing the following criteria: purpose, content validity, face validity, feasibility, construct validity, and reliability. The Critical Appraisal of Classification Systems was modified where appropriate to fit the purpose of this review. The rubric and scoring system are presented as tables, along with modifications to the tool and the justification for these modifications, in Supplemental Digital Content 2 (http://links.lww.com/CJP/A658).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The primary purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize the definitions and characteristics of different PMCs presented by different authors or groups. The extracted data were qualitatively synthesized via thematic analysis and convergence of terminology.

The first step involved allocation of PMC into groups with similar meaning. Two reviewers (M.A.S. and H.M.-A.) independently allocated all proposed PMC into groups. First, PMCs that used descriptions that were aligned with the current consensus of pain definitions proposed by the IASP as either nociceptive, neuropathic, or nociplastic (Table 1) [22] were allocated to those major categories. Convergence of PMCs into these categories despite different terminology was based on the term, its definition, and the described characteristics or features of the PMC. Subtypes of the 3 major categories, if mentioned by papers, were also allocated. Second, PMCs that could not be categorized to the 3 major categories were allocated to additional groups as follows: PMCs that described “sympathetic pain” and “psychogenic pain” mechanisms were allocated to a “disputed” category. PMCs were allocated to a “mixed” category if it clearly described a mix of separate mechanisms (eg, nociceptive and central mechanisms), without identification of a predominant PMC, and thus could not provide information that would aid differentiation between PMCs. Any individual PMC that did not share similarities with any of the nominated PMC groups was categorized to an “other” category, which included PMCs referring to “idiopathic/unknown” mechanisms, specific diseases or conditions, and “unclear” if insufficient information was provided for allocation. The mixed and other categories were not included in the subsequent thematic analysis (see below).

After independent allocation of PMCs by M.A.S. and H.M.-A., a third reviewer (L.M.H.) compared the allocations and identified differences. Any differences in allocation to groups between reviewers were resolved by discussion with a fourth reviewer (P.W.H.). A table was generated with the diversity of terms used for presentations with a specific PMC. Terms with alternative spelling or prefixes/suffixes (eg, nociceptive and nocioceptive, physiologic, and physiological) were combined. For this step, analysis involved calculation of the number of times that a term was mentioned across papers (frequency) and percentage of papers that used a term relative to all terms used for each PMC.

The second step involved thematic analysis to evaluate the features proposed, by authors of the identified classification systems, to characterize each PMC. After reading through the extracted data, 3 reviewers (M.A.S., H.M.-A., P.W.H.) proposed possible themes that would capture concepts of similar meaning and account for the majority of the extracted data.

After discussion, 3 main topics for organization of the thematic data were proposed: (1) underlying neurobiology/pathology, (2) aggravating factors, easing factors, and response to treatment, and (3) pain characteristics.

Data extracted for each PMC were first organized into major themes within the main topic areas. For instance, within the main topic “underlying neurobiology/pathology,” extracted data were allocated to major themes such as “tissue damage or input,” “nervous system damage,” etc. Once this broad allocation was agreed by the reviewers, data allocated to each major theme was further subdivided into subthemes. For example, the theme “Pain location” was divided into subthemes such as “localized pain,” “diffuse, widespread, generalized pain,” etc. Allocation to subthemes was undertaken by M.A.S. and reviewed by P.W.H. and H.M.-A.

Once all reviewers agreed with the allocation, the subthemes were analyzed to evaluate those that converged within a specific PMC (eg, what are the most commonly reported “pain characteristics” associated with a specific PMC, as reported by authors) and subthemes that diverged (eg, where authors propose contrasting characteristics of pain within a PMC). For this step, analysis involved quantification of the proportion of papers that included a specific subtheme. Tables were generated for each major topic to highlight convergent features that were unique to a PMC, those that overlapped with other PMCs, and features that diverged.

Using this thematic analysis, the description of each PMC category was summarized. In description of the analysis, standard terms are used throughout the text to describe the frequency of reporting of a specific subtheme: “most” discussed by 75% or more papers, “many” for 25% to 74%; “several” for 10% to 24%; “some” for 3% to 10%; and “few” for <3% of papers.

Note that it was originally indicated in the registered study protocol “to propose an overarching mechanism-based classification that takes into account the diverse opinions presented in the literature.” However, as most classifications could be included within the framework proposed by IASP, rather than creating a new classification, we addressed the intention of this aim by focusing the analysis on detailed evaluation of areas of convergence and divergence.

RESULTS

Paper Characteristics and Quality

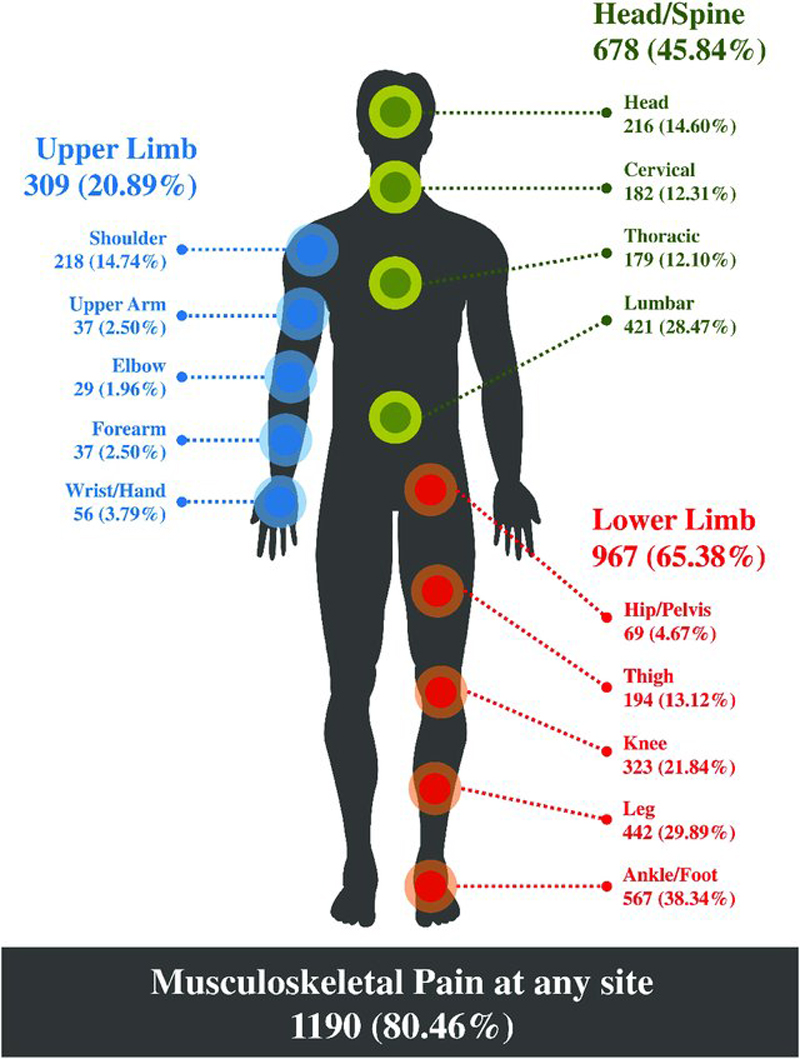

Figure 1

Table 2 The search strategy yielded 11,874 papers from the 3 databases. After removal of duplicates and ineligible papers, and searching the references for eligible papers, 224 papers were included. The number of papers at each step and the reasons for exclusion are presented in Figure 1. A summary of the methods used in each paper to develop the proposed mechanism-based classifications is presented in Table 2.

The evaluation of the included papers according to the Critical Appraisal of Classification Systems is presented as a table in Supplemental Digital Content 3 (http://links.lww.com/ CJP/A659). The critical appraisal tool identified that for content and face validity, many did not address mixed categories (criterion 3a), lacked consensus and/or validation in development of classification (criterion 4), did not propose clear criteria for inclusion into PMCs (criterion 7), and/or did not discuss the validity/reliability of the criteria (criterion 7b). For feasibility, most classifications were not simple to perform in a clinical setting (criteria 11 to 12) because of the requirement for extra resources (eg, skills, training, equipment; criterion 13). For validation and reliability, most papers could not be scored as this was not addressed (criterion 15, 17 to 18). Some of the most developed and highest-scoring classification systems across criteria are those developed by Smart and colleagues, [19–21, 174] Schafer and colleagues, [40–42] and Dewitte and colleagues. [24, 25]

Allocation to Pain Mechanism-based Classification Categories

Table 3

page 5+

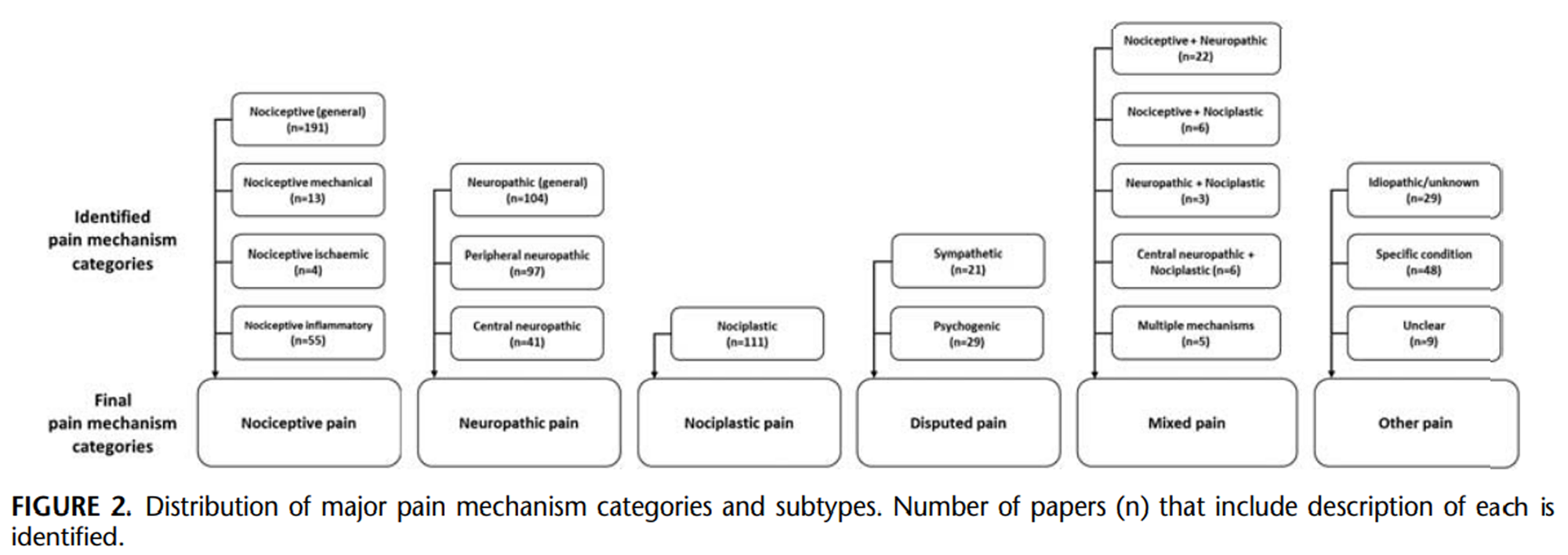

Figure 2 A total of 174 different terms were used to identify PMCs (Table 3). Consensus was reached to converge PMCs to the 6 a priori defined categories (Figure 2). This included the 3 major categories of Nociceptive, Neuropathic, and Nociplastic with 8 subtypes, a Disputed category that included the debated terms of sympathetic and psychogenic pain, and categories that clustered PMCs that were Mixed or Other.

Nociceptive Pain

Of the 224 included papers, 198 papers included 264 PMCs that were identified in the papers to involve nociceptive input from the tissues. Many of these PMCs (44.7%) use the term “nociceptive pain” to describe this mechanism (Table 3). Other terms used to describe nociceptive pain include somatic pain (6.5%) or musculoskeletal pain (8.7%) (Table 3).

Many of the PMCs (72.4%) in this category described nociceptive pain as a single type; others defined subtypes. The 27.6% of PMCs that described subtypes of nociceptive pain used the rationale that these subtypes can be differentiated clinically. [23, 175] Nociceptive mechanical pain was described in 13 PMCs as a subtype. The term used most frequently for this subtype of nociceptive pain was “mechanical pain” (2.7%) (Table 3). Nociceptive ischemic pain was described in 4 PMCs as nociceptive pain induced by ischemia. Nociceptive inflammatory pain was described in 55 PMCs and considered to involve inflammation as the stimulus for nociceptive input. The terms used were “inflammatory” (11.7%), “peripheral sensitization” (1.1%), or “peripheral nerve sensitization” (1.9%). A key area of divergence between papers was some papers consider that the term “nociceptive pain” should be used only for a transient pain that reflects the normal function of the nociceptive pathway; whereas others consider that nociceptive input can be maintained by mechanisms such as inflammation.

Neuropathic Pain

Of the 224 included papers, 182 papers included 242 PMCs that were considered by the authors to involve damage, lesion, or disease to the nervous system as the mechanism to drive or maintain the pain experience. Many papers (42.1%) used the term “neuropathic pain” to describe the single category; few used the terms “neurologic” (0.4%) or “neurogenic pain” (1.2%), but most used terms that identify a specific element of the nervous system (Table 3).

Although many PMCs (43.0%) described neuropathic pain as a single category, others described subtypes (57.0%). Peripheral neuropathic pain was identified in 97 PMCs as pain involving damage, lesion, or disease to the peripheral nervous system. Several PMCs (15.3%) use the term “peripheral neuropathic pain,” whereas several others (10.3%) use this definition for all neuropathic pain. Other terms used are “peripheral neurogenic pain” (5.0%), “deafferentation” (0.8%), “denervation” (2.5%), or “radicular” (2.9%) (Table 3). Central neuropathic pain was identified in 41 PMCs and was considered to involve damage, lesion, or disease to the central nervous system (CNS). Some PMCs (9.1%) use the term “central neuropathic pain,” whereas some (3.7%) used the term “central pain,” which can be confusing, as this term is also used to describe pain that is predominantly maintained by altered nociceptive processing (see next section, Nociplastic Pain).

Nociplastic Pain

Of the 224 included papers, 106 papers included 127 PMCs that were considered by the authors to involve a pain maintained by altered nociceptive processing. [22] Many (37.8%) PMCs use the term “central sensitization” (Table 3). Some (3.6%) PMCs classify this category under neuropathic pain originating from the CNS and use the term “central neuropathic pain,” as they consider that this represents a dysfunction of the nervous system. Other terms used are “central pain” (14.4%), “centralized pain” (7.2%), “functional pain” (16.2%), and “dysfunctional pain” (10.8%). The term “nociplastic pain” was adopted in 2016 by the IASP11 and has been used by some (9.0%) authors since that recommendation.

Disputed Pain Categories

Sympathetic pain was identified by 21 papers and described in 21 PMCs as involving the autonomic nervous system. Although originally described as a separate category of pain, some authors recommend it as a subtype of neuropathic pain. [43, 240–242] Although not all agree, aspects of this PMC are now commonly referred to as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS; type 1 without nerve damage and type 2 with nerve damage). [240] The absence of nerve damage as a criterion for CRPS type 1 differs from the general definition of neuropathic pain, except that several authors highlight evidence for dysfunction of the nervous system [7, 240] and has been argued to involve the nervous system at later stages. [214, 243] Others consider CRPS type 1 to fall under nociplastic pain. [244] Hence, this pain category remains controversial. The most commonly used terms to describe this PMC are “sympathetic pain” (38.1%) or “sympathetically maintained pain” (42.9%; Table 3).

Psychogenic pain was described in 28 papers and included 29 PMCs that were considered by authors to involve pain caused or driven by psychological factors. The mechanism through which psychological issues are believed to mediate the pain experience is generally regarded to involve altered processing of nociception, that is, nociplastic mechanisms. [12, 13] Thus, psychogenic pain might be considered to converge with nociplastic pain. Many (58.6%) PMCs used the term “psychogenic pain” to describe this category, whereas others used “affective pain” (13.8%) and “cognitive pain” (6.9%; Table 3).

Mixed and Other Categories

After classification, 137 PMCs, using 61 unique terms, could not be allocated to the major or disputed categories. Forty-two PMCs used 21 terms to describe mixed pain subtypes (Table 3). As these subtypes refer to a combination of PMCs, they could not be attributed to any 1 of the 3 major categories. They were separately grouped under a mixed pain category (Fig. 2). As expected, by definition, mixed pain subtypes are described to share features or characteristics of 2 or more PMCs. The mixed pain subtypes category was not included in the thematic analysis because this term was generally used without clarification of the specific features that underpin the dual categorization and it does not permit interpretation of features that characterize/ distinguish the main PMC.

Eighty-six PMCs used 41 terms (Table 3) that were identified as other if they referred to pain that was clearly stated to have unknown/idiopathic mechanisms (n= 29), related to a specific disease, and could not be generalized (n= 48; eg, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, and orofacial pain), or unclear (n= 9) if the paper did not provide sufficient description to be allocated. PMCs allocated to the other category were not included in the thematic analysis because most failed to provide details of features of the grouping, and consideration of the conditionspecific PMCs did not serve the overall goal of this review.

Thematic Analysis of PMCs

Table 4–6

page 9+The thematic analyses of the data extracted from each paper for the 3 major pain categories and the 2 disputed pain categories were evaluated according to the 3 main topics of (1) underlying neurobiology/pathology, (2) aggravating factors, easing factors, and response to treatment, and (3) pain characteristics. Summary data are presented in Tables 4–6 and complete data are presented as extensive tables for each of the 3 main topics in Supplemental Digital Contents 4 to 6 (http://links.lww.com/CJP/A660, http://links.lww.com/CJP/A661, http://links.lww.com/CJP/A662). Key findings are summarized below to define and characterize how each major/other PMC and subtype is described in the literature.

Nociceptive Pain

The thematic analysis was carried out on 264 PMCs that were considered by the authors to involve nociceptive input from the tissues. Table 4 summarizes this pain type on the basis of thematic analysis and the main topic areas. Key convergent characteristics of this PMC include pain in response to peripheral noxious stimuli, involves damage to non-neural tissue, is provoked by movement and postures, and is localized. Some areas of divergence were identified. Some authors consider inflammatory and nociceptive pain to be different categories, whereas others consider them to be subtypes of an overarching nociceptive mechanism. Some authors consider that all nociceptive pain is invoked by or involves inflammation. [44, 45] Although most consider nociceptive pain to be characterized by its localization, some describe it as diffuse and hard to localize pain. [46] Many (26.7%) consider this pain to be provoked by movements, postures, etc., but it has also been described as continuous in nature. [237]Subtypes of Nociceptive Pain. Nociceptive mechanical pain was considered by authors to involve a mechanical source of nociceptive input. Nociceptive mechanical pain is characterized, as described by authors, by all features of nociceptive pain described in Table 4, but with an emphasis on mechanical stimuli. Themes described by authors include mechanical peripheral noxious stimulus (30.8%); provoked by movement (30.8%), activity (23.1%), postures (7.7%), or pressure (15.4%); and can be relieved by rest (15.4%).

Nociceptive ischemic pain, as described by authors, is characterized by all features of nociceptive pain, but with evidence or suggestion of a response/nociceptive input secondary to constricted blood flow to the tissue. Nociceptive ischemic pain is believed to be provoked by postures, especially if sustained, and relieved when the provoking posture is changed (75.0%), and unresponsive to anti-inflammatory drugs or application of ice (25.0%).

Nociceptive inflammatory pain, as described by authors, is characterized by all features of nociceptive pain, but the focus is that this subtype is driven by an inflammatory stimulus. Few papers (3.0%) considered all nociceptive pain to involve inflammation and reserved the term “nociceptive pain” for the transient physiological process of nociception, [9, 15, 47–49, 217] with one paper considering all pain to be driven by inflammatory processes. [50, 51] Many (29.1%) suggest that it may involve hyperalgesia/hypersensitivity, or even mechanical and thermal allodynia (10.9% [52–55]). Nociceptive inflammatory pain is described to be provoked by movements (21.8%) and pressures (7.3%) and responsive to anti-inflammatory drugs (12.7%). Signs of inflammation (redness, heat/warmth, and swelling) are highlighted by several papers as a key feature of this PMC (21.8%). An area of divergence is that one author states that inflammatory pain involves diffuse hyperalgesia and/or allodynia, [53] which others would consider to be a feature of nociplastic pain. Several (14.5%) papers suggest that it may involve spontaneous or stimulus-independent pain, which again may not infer nociceptor involvement, whereas others (7.3%) consider it to be stimulus dependent.

Neuropathic Pain

The thematic analysis was carried out on the 242 PMCs that were considered to involve neuropathic mechanisms defined as involving damage, lesion, or disease to the nervous system that is driving or maintaining the pain experience. Table 5 summarizes this pain type on the basis of thematic analysis and the main topic areas. Key characteristics of this PMC, as described by authors, include history or evidence of damage or disease of somatosensory system; pain following a neuroanatomically plausible distribution; with burning or electric-shock-like quality; and associated with paresthesias/sensory deficits. There were some areas of divergence. Several authors considered neuropathic pain to be due to dysfunction or maladaptive processing within the nervous system (18.1%), which is more commonly considered to be a characteristic of nociplastic pain. One author (2.4%) suggests that it can involve permanent and irreversible changes within the CNS. [218] Further, one author exclusively stated that central neuropathic pain is caused by “central sensitization” mechanisms. [232] Another author states that neuropathic pain does not adhere to nerve distributions, [56] which again suggests blurring between neuropathic and nociplastic mechanisms.Subtypes of Neuropathic Pain. Peripheral neuropathic pain is described by authors to be characterized by most features of neuropathic pain, with a history or evidence of damage or lesion to the peripheral nervous system (eg, nerve root) (71.1%). One author suggests Peripheral neuropathic pain can be differentiated from Nociceptive inflammatory pain by the presence of mechanical and/or cold allodynia and/or paresthesias/dysesthesias. [57] Unlike other neuropathic pain, peripheral neuropathic pain is thought to be aggravated by movement and activity that loads the peripheral neural tissue (16.5%).

The authors suggest that Central neuropathic pain is characterized by features similar to the general neuropathic pain category, but involves evidence or history of damage, lesion, or disease to the CNS (68.3%). The authors suggest that the feature that could distinguish central from peripheral neuropathic pain is that the former is continuous/constant (24.4%) and spontaneous/stimulus independent (19.5%), [58] whereas the latter is intermittent/transient (5.2%) and evoked/stimulus dependent (9.3%) [58] (although this diverges from others, who argue that neuropathic pain in general is continuous), and central neuropathic pain is unresponsive to a peripheral nerve block (4.9% [59]).

In Parkinson disease, a CNS disease, central neuropathic pain is described as fluctuating and is relieved by levodopa, has qualities described as formication, scalding, relentless bizarre quality, boring, and ineffable, and involves an urge to move. [60]

Nociplastic Pain

The thematic analysis was carried out on the 111 PMCs that were presumed to be maintained by altered nociceptive processing and generally consistent with the IASP definition for nociplastic pain (Table 1). [22] Table 6 summarizes this pain type on the basis of thematic analysis and the main topic areas. Key characteristics of this PMC, as described by authors, include a state of amplified/increased excitability or neural signaling within the CNS in response to normal or subthreshold afferent input; pain that is disproportionate to the nature of pathologic changes or injury; presence of hyperalgesia, allodynia, and temporal summation; a disproportionate, nonmechanical, unpredictable pattern of pain provocation in response to multiple, nonspecific aggravating, and easing factors; persists beyond the expected tissue or pathology healing time; follows a diffuse, widespread, generalized, poorly localized, or nonanatomic pain distribution; and is constant or unremitting even at rest. This category has been heavily debated in the literature. As mentioned above, some authors consider some of the features of nociplastic pain to infer neuropathic pain. A major divergence is that some consider altered nociceptive processing to potentially have underlying disease or lesion of the CNS and therefore consider it as central neuropathic pain, [232] and others consider “central pain” to be caused by not only dysfunction but also damage or disease of the CNS [219]; however, this is before the redefinition of neuropathic pain. [245, 246]

Disputed Pain Categories

Some authors describe sympathetic pain to be characterized by features that reflect those of neuropathic pain but relate to the autonomic component of the nervous system (38.1%). Many state that a sympathetic block can provide complete or near complete pain relief (33.3%); few (4.8%) state that sympathetic pain can be worsened by cold weather or psychological factors (eg, stress), [61] is independent of movement or position, [44] can be deep, [44] or even initially be confined to a nerve distribution but can spread beyond these confines. [62] Several (19.0%) state that sympathetic pain can involve allodynia or hyperalgesia/hypersensitivity. Some (9.5%) state that it can be boring, ongoing, or persistent, and can involve wind-up pain or hyperpathia (an abnormally painful reaction to a stimulus, especially a repetitive stimulus, and an increased threshold22). Others state that the pain can be burning (14.3%), throbbing (4.8%), or like a lightning/shock (4.8%).

Others state that sympathetic pain may involve vasomotor changes such as temperature (28.6%) and skin color changes (38.1%), sudomotor changes such as swelling (28.6%) and sweating (33.3%), motor/trophic changes (33.3%) such as decreased range of movement, weakness, dystonia, tremor, and skin/hair/nail changes. Paresthesias or dysesthesias (eg, pins and needles, tingling; 9.5%) or hypoalgesia (4.8%) can be present. As previously mentioned, the new terminology of CRPS 1 and 2 highlights divergence of opinion, with features that overlap with different major pain categories. [244]

Psychogenic pain was characterized, as described by authors, by many features of nociplastic pain, but many argue that the primary cause is a psychiatric disease or significant psychological features or turmoil (33.3%). There may have been an initial injury (13.3%) or organic pathology (3.3%). Some consider that the autonomic nervous system may be involved (3.3%). Psychogenic pain, as described by authors, presents with features of acute anxiety (3.3%), affective factors such as emotions and feelings (6.7%), concerns for bodily function (6.7%), and cognitive factors (13.3%; eg, maladaptive behaviors and understanding of pain, and fear-avoidance behaviors). Also, it may be aggravated by significant psychological features such as emotion, anxiety, or depression (16.7%). The authors argue that psychogenic pain does not respond to removal of tissue pathology, if it exists, or to modifying input to CNS (3.3%), but placebo (isotonic saline injection) can lead to complete or long-lasting relief (13.3%). Many features described by authors overlap with nociplastic pain, but with the abnormal processing of pain mediated by primary psychological/psychiatric features.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review aimed to synthesize and summarize the vast literature on descriptions of mechanism-based classifications for pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system as described by authors. On the basis of the definitions and features published in a variety of formats, most PMCs could be broadly aligned with the 3 major groupings proposed by the IASP: nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic (Table 1). [22] We also identified classification on the basis of the disputed pain categories of sympathetic and psychogenic pain, and mixed or other categories. The categories encompassed a multitude of terms and characteristics. Although there was substantial convergence, some important areas of divergence of opinion were identified.

Methods to Develop Mechanism-based Classifications for Pain

A range of methods has been used to develop or propose classifications on the basis of mechanisms. Although consensus is considered important for controversial topics with divergent opinions, [247, 248] a limited number of papers (4.4%) involved a consensus approach (eg, Delphi, expert panel). [8, 18, 24, 63] Few (2.7%) were systematic reviews, which aim to limit bias and consider consistency and heterogeneity to produce robust conclusions. [249, 250] Instead, many classifications were proposed or stated in narrative reviews (64.7%), which are limited by potential bias from selective reporting of the literature, variation in critical appraisal and syntheses, and author opinion. [251] We judged the quality of process undertaken to develop the classifications according to a scale devised to assess classification systems. When assessed in this manner, most classifications received a partial score on the method of development (criterion 4) as they did not involve consensus and/or validation processes (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links. lww.com/CJP/A659), which is unsurprising as many were in the form of narrative review (64.7%).

The present study provides the first comprehensive systematic review of mechanism-based classifications of pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system, presenting the vast convergent and divergent views presented in the literature, which provides a foundation to progress to a consensus approach to refine the clinical classification.

Major Mechanism-based Classification Categories and Areas of ConflictNociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain was agreed by most authors to refer to pain that is evoked and/or maintained by nociceptive input from tissues, which agrees with the IASP definition (Table 1). [22] Some subdivide this classification on the basis of the presumed nociceptive stimulus (eg, mechanical, ischemic, inflammatory).

Some challenges arise for identification of this pain mechanism. First, clinical proof of ongoing nociception is difficult to obtain. Nociceptive neuron discharge can be detected with specialized techniques such as microneurography, [252, 253] but this is not easily implemented and cannot be used for all situations. Although some argue that involvement of nociceptive input has been supported using blinded anesthetic blocks [254]; in some specific cases, this method requires careful control of potential placebo effects. In most cases, clinical identification depends on history, pain characteristics, and aggravating and relieving factors.

Second, opinions diverge on what pain presentations should be included under the umbrella term of nociceptive pain. Some argue that inflammatory pain is distinct to nociceptive pain, [15] whereas others consider it a subtype [255] in which nociceptive input is maintained by an inflammatory process (eg, peripheral sensitization [64]). Others use the term “inflammatory pain” to refer to any noxious input from tissue damage, irrespective of the noxious modality. [9, 15, 47–49] Further, some limit nociceptive pain to reflect the normal transient physiological response to a noxious stimulus (eg, pin-prick) without tissue damage, [9, 15, 47–49, 217] whereas others exclude this transient response from the clinical entity of nociceptive pain. [52, 54, 65, 220] On the basis that nociceptive pain is an experience of pain that is evoked and/or maintained in response to activity of nociceptive neurons, we included both transient pain and pain associated with tissue damage as nociceptive pain. It is noteworthy that many of the mixed pain categories include nociceptive plus either neuropathic or nociplastic mechanisms. This highlights the view of many authors that once persistent, nociceptive pain will be accompanied by other mechanisms. Whether pain can be primarily maintained by nociceptive input is an issue that requires clarification. [256, 257]

Neuropathic Pain

Consistent with the IASP definition (Table 1), [22] neuropathic pain is generally considered by authors to involve damage or dysfunction/disease of the nervous system. Some divide this on the basis of the region of the nervous system (ie, peripheral and central). Whether neuropathic pain should be considered a pain related to the musculoskeletal system requires consideration. Neuropathic pain was included in this review as it is often experienced in the musculoskeletal system and requires differentiation from the other pain mechanisms.

There is disagreement on reference to damage or dysfunction. Some argue that damage must be present [245, 246]; others challenge the definition of dysfunction, [258] which has been removed from the definition in 2011. [245, 246] However, what constitutes dysfunction is sometimes unclear, [24, 66, 67] and in some cases considered to include abnormal processing leading to confusion with nociplastic mechanisms. Divergence of opinion is demonstrated by some who consider that neuropathic pain requires evidence of nerve injury, whereas others consider neural inflammation and sensory changes (eg, paresthesias, allodynia) sufficient. [176, 221] This creates confusion as sensory changes can also be present in other pain types (eg, nociplastic). Compounding this divergence of opinion, others consider that the neuropathophysiological process of central sensitization (defined by the IASP as increased responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the CNS to their normal or subthreshold afferent input [22]) dominates [68] or exclusively causes [221, 232] neuropathic pain, and is, thus, an example of dysfunction of the nervous system on the basis of their definition, again creating overlap with nociplastic pain. Interestingly, some papers have used the term “peripheral sensitization” to describe neuropathic pain, [44, 69] where it has also been used to describe nociceptive pain (Table 3). This term reflects a neurophysiological process defined as the increased responsiveness and reduced threshold of nociceptive neurons in the periphery to the stimulation of their receptive fields, [22] and we recommend that it should be reserved for describing this process rather than a PMC.

There has been specific debate on fibromyalgia; some describe it as neuropathic pain, because it involves nerve damage [68, 70, 232] and changes in the density of small diameter afferents, [259] whereas others refer to nociplastic mechanisms as a basis for this condition, because symptoms are explained by central sensitization. [11] The use of dysfunction in the definition [24, 66, 71, 232, 260] and the fibromyalgia debate suggest that some literature still deviate from the 2011 definition of neuropathic pain, [245, 246] and do not yet consider the recent definition of nociplastic pain. [22]

Nociplastic Pain

Nociplastic pain has recently been defined by the IASP as “pain that arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain.” [22] In this case, pain has been generally considered by authors as being maintained by the altered central processing including central sensitization, hence the alternate terms of “central pain” or “central sensitization pain.”

There has been considerable debate on terminology and characteristics. [11, 22, 261, 262] First, as highlighted in the preceding section, some consider this pain mechanism a subgroup or subset of neuropathic pain as it could be considered to represent dysfunction of the CNS. [68, 232]

Second, some argue against using the term “central sensitization,” [263] as it refers to a neurophysiological mechanism that is inferred from clinical measures (eg, allodynia and hyperalgesia [22]) and cannot generally be measured directly. Central sensitization is also involved in other pain mechanisms (eg, neuropathic pain) as was identified in the numerous references to mixed pain types. Third, others argue that because the cause is unknown, terms such as “unknown pain” and “idiopathic pain” should be used, [11, 72, 73] which suggests overlap between nociplastic and some of the groups that we allocated in the group Other. As these terms provide no insight into the putative underlying mechanisms, there is concern that using such terms may stigmatize many patients, [264, 265] and provides limited guidance for management. [11] The term nociplastic was developed to resolve these and other issues and is derived from “nociceptive plasticity,” which reflects change in the function of nociceptive pathways. [11]

Some challenge the term “nociplastic pain” as there is no specific structural pathology, [11] the term is imprecise and vague, [261, 262] and because most, if not all, cases of persistent pain involve altered central processing and plastic changes. [261] Others argue that commonly used terms that suggest pain origin (eg, centralized pain, central sensitization, central hypersensitivity) should be used. [262] The definition provided by the IASP is also somewhat confusing as it includes reference to “no clear evidence of … threatened tissue damage.” This implies pain without tissue damage and concurs with features described for nociplastic pain. The present review provides a comprehensive summary of the varied terminology, the clinical features that authors attribute to this PMC, and features that may differentiate this PMC from others as described by authors. Although there is some divergence of opinion, we found a high degree of consistency, which should provide a strong foundation to further consider this debate.

Disputed Pain Categories

The allocation of sympathetic pain is not without question as it has been argued that its signs and symptoms are generated by the sympathetic nervous system in response to sensitized input, [7] which implies dysfunction rather than damage to the nervous system. As an alternative to the term, expert consensus developed the term complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) to describe aspects of this presentation, with 2 types — type 1, which involves no nerve damage (which some consider to be nociplastic), [244] and type 2, which involves nerve damage (which would fit into neuropathic pain by definition). [214, 240]

Further discussion is required to resolve whether this presentation of pain should be considered a subclass of neuropathic pain, [43, 240–242] nociplastic pain, [244] a mixed pain state, [266–268] or as a separate entity. [44, 61, 222]

Psychogenic pain is considered to be an outdated term by some [244] and no longer listed in pain terminology by IASP, whereas others argue for it as a unique pain mechanism group. [26, 74, 75] On the basis of the premise that, in psychogenic pain, perhaps psychological and cognitive factors are likely to maintain pain by an impact on nociceptive/pain processing in the CNS [12] and sensitization, [16] it is plausible to consider possible convergence of Psychogenic with the nociplastic pain category. This may not be universally accepted, and the present summary should form a basis for ongoing discussion.

Limitations of Mechanism-based Classifications

Overlap among underlying neurobiological mechanisms is common. Although one mechanism may predominantly contribute to the pain experience, multiple mechanisms will be present for many. Many authors agree that individuals with ongoing nociceptive input will also have central sensitization. [65, 76, 77, 217] Some authors created mixed categories, [71, 78] whereas others advocate attempts to discriminate a predominant/primary mechanism. [7, 8, 23, 24, 63, 177]

The 3 major PMCs proposed by IASP and reinforced by this review provide a general framework to consider differentiation of patients to guide management [8, 220] and prediction of prognosis, etc. As highlighted here, these can be further subdivided, which would be expected to further refine decision-making. However, although the IASP provides definitions for these PMCs, a lack of consensus-driven criteria is a major issue for nociceptive and nociplastic pain. Development of criteria to determine the presence of nociplastic pain is a challenge as it relies, by definition, on the exclusion of nociceptive pain, for which criteria do not exist.

A major objective of this review was to summarize the features proposed by authors (neurobiological features, pain characteristics, aggravating, and easing factors) that characterize each PMC and consider the convergence or divergence of opinion. For each PMC, some features were largely consistent. However, many of these features also overlap among most PMCs, which is expected, as mechanisms could overlap. For this reason, some authors state that pain characteristic features cannot identify mechanisms as they are not specific. [16] Further, many diagnostic tools have poor validity and reliability. [10] A combination of measures is likely to be required and might include objective measures and response to pharmacological agents that target specific neurobiological mechanisms. [16, 17] A major challenge is validation as there is no objective gold standard against which they can be compared. This review provides an overview of potential factors that can inform future work.

Study Limitations

Several limitations required consideration when interpreting the findings of this review. First, defining the term “mechanism” was sometimes challenging. We considered mechanism to refer to the general groupings of neurobiological processes involved in the pain experience and all screened papers were considered with respect to this definition. Some papers that did not express this explicitly may have been excluded. It is important to consider that within the 3 main PMCs, a range of specific neurobiological processes are possible and not yet completely understood.

Second, we aimed to consider “pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system,” but excluded pain related to the viscera, surgery, and cancer. Although these pain groups can be experienced in the musculoskeletal system, they present specific stimuli/pathologies that were beyond the scope of this review.

Third, we only considered studies in English, which may have excluded classifications and opinions in other languages. Fourth, we included studies across a broad range of types that would vary in quality of control of bias. We considered this to be appropriate for this review as we considered it a priority to identify the breadth of views presented in the literature. Quality was difficult to judge with this diversity of methods, and we adapted the Critical Appraisal of Classification Systems tool to provide quantification of key quality aspects that could be used across the diversity of included studies. Fifth, screening and data extraction were undertaken by one reviewer, which may allow potential bias. However, according to the principles expressed in AMSTAR [2, 269] a second reviewer undertook screening and data extraction for a sample of papers and achieved acceptable agreement ( >80%) before completion of the task. Sixth, convergence of PMCs was based on interpretation of descriptions provided by authors. We acknowledge that some ambiguity may have been misinterpreted. All data are presented in the Supplemental Digital Contents 4 to 6 (http://links.lww.com/CJP/A660, http://links.lww.com/CJP/A661, http://links.lww.com/CJP/A662) for readers to consider.

Finally, we did not include details of methods that could be used to discriminate between PMCs (eg, questionnaires— PainDETECT, [270] Central Sensitisation Inventory [178]; clinical tests—quantitative sensory testing [271]). This review aimed to consider the features of each pain group, and separate work should carry out detailed analysis of identification and discrimination of those features.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper describes an extensive systematic review and synthesis of mechanism-based classifications of pain experienced in the musculoskeletal system. We report a convergence, and divergence, of diverse nomenclature, descriptions of neurobiology, pain characteristics, and aggravating/easing factors. There was considerable agreement, but some inconsistency and evolution of terminology. A next step is clarification of models and methods to differentiate pain mechanism categories (PMCs) and reach expert consensus. This review provides a summary of the current state of the literature that can support that process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the valuable contribution of Nathalia da Costa, BSc (Hons), School of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences, The University of Queensland, QLD, Australia, for her assistance in the development of the search strategy.

References

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Since 2-23-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |