The Global Spine Care Initiative:

Classification System for Spine-related ConcernsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 889–900 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Scott Haldeman, Claire D. Johnson, Roger Chou, Margareta Nordin, Pierre Côté, Eric L. Hurwitz, et al.

Department of Epidemiology,

School of Public Health,

University of California Los Angeles,

Los Angeles, CA, USA

PURPOSE: The purpose of this report is to describe the development of a classification system that would apply to anyone with a spine-related concern and that can be used in an evidence-based spine care pathway.

METHODS: Existing classification systems for spinal disorders were assembled. A seed document was developed through round-table discussions followed by a modified Delphi process. International and interprofessional clinicians and scientists with expertise in spine-related conditions were invited to participate.

RESULTS: Thirty-six experts from 15 countries participated. After the second round, there was 95% agreement of the proposed classification system. The six major classifications included: no or minimal symptoms (class 0); mild symptoms (i.e., neck or back pain) but no interference with activities (class I); moderate or severe symptoms with interference of activities (class II); spine-related neurological signs or symptoms (class III); severe bony spine deformity, trauma or pathology (class IV); and spine-related symptoms or destructive lesions associated with systemic pathology (class V). Subclasses for each major class included chronicity and severity when different interventions were anticipated or recommended.

CONCLUSIONS: An international and interprofessional group developed a comprehensive classification system for all potential presentations of people who may seek care or advice at a spine care program. This classification can be used in the development of a spine care pathway, in clinical practice, and for research purposes. This classification needs to be tested for validity, reliability, and consistency among clinicians from different specialties and in different communities and cultures. These slides can be retrieved under Electronic Supplementary Material.

KEYWORDS: Back pain; Critical pathways; Delphi technique; Neck pain; Spinal diseases

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Spine-related pain and symptoms are ubiquitous in societies across the globe [1, 2]. People with spinal disorders commonly present to clinicians and spine clinics with neck, mid back, or low back pain. However, people may also present with complaints that are more serious than localized spine pain including deformity, inflammatory, infectious, or neoplastic disorders. Furthermore, clinicians who manage spinal disorders may be approached with concerns about structural spine pathology found incidentally in a diagnostic imaging study or with an observed deformity, such as scoliosis. Family, friends, and employers may rely on spine care providers and programs for information and answers to questions about prevention or prognosis of spinal disorders and related disability.

World Spine Care is a multinational, not-for-profit, charitable organization founded in 2008 [3]. It was launched to fill the gap in the evidence-based treatment of spinal conditions found in underserved areas around the world. World Spine Care developed the Global Spine Care Initiative (GSCI) to reduce the global burden of disease and disability by bringing together leading health care scientists and specialists, government agencies, and other stakeholders to transform the delivery of spine care worldwide but especially in underserved and low- and middle-income countries. The mission of the GSCI is to develop an evidence-informed, practical, and sustainable, care pathway and spine health care model for communities with various levels of resources around the world [4–6].

A successful care pathway requires the ability to categorize individuals who present with concerns for triage and management. To satisfy the GSCI mission, the classification must address anyone presenting with a spine concern. Therefore, it is not sufficient to consider a system limited to one area of the spine, one pathological process, non-specific spine pain, or only those people who may be concerned about disability. The classification system must include all possible patient presentations, including common and uncommon spinal symptoms and diagnoses. The system must be able to identify individuals whose symptoms have strong psychological or social components and those that are associated with systemic disorders or comorbidities. In addition, the system must be adaptable or responsive to different cultures and traditions and be flexible to accommodate differing levels of available resources. The purpose of this paper is to present a classification system for spine-related concerns that would apply to all persons with spine-related concerns and that can be used in an evidence-based spine care pathway.

Methods

Overview

The GSCI Principal Investigator (SH) and Scientific Secretaries (MN, RC, PC, EH) invited internationally recognized, interprofessional authors, policy and opinion leaders, scientists, and clinicians with expertise and interest in spinal disorders to participate in the GSCI classification development process. After the initial list of invitees was developed, the experts were asked for additional participant recommendations. During this initial process, GSCI Principal Investigators focused on including representatives from a broad range of disciplines and nations. Criteria for the classification system were developed to meet the mission of the GSCI (see Online Resource Figure 1 for criteria for the development of the classification system for spine-related concerns).

Review of spine classification systems

Table 1 A search of the literature was performed and input from the members of the GSCI was collected to identify classification systems that could meet the criteria for the development of the care pathway and implementable model of care. The literature search revealed many papers classifying the severity of specific spine pathologies such as vertebral body fractures, scoliosis, disk herniation or degeneration but failed to identify classification systems that would apply more generally to people with spine-related symptoms or concerns. Members of the GSCI then identified 10 extant spinal disorders classification systems that were widely used or proposed for clinical guideline or research considerations and that addressed people presenting with spine-related symptoms (Table 1) [7–17].

One of the most widely used classification systems to differentiate spinal disorders by clinicians and payers in high-resource countries is the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) developed by World Health Organization (WHO) [7]. The ICD-10 lists over 300 diagnostic codes which could apply to people who present with spinal symptoms or diagnoses. The use of the ICD requires a specific, often pathological diagnosis. Most of the ICD codes focus on an exclusive biomedical approach to spinal disorders [7]. This classification, although helpful in tracking diagnoses, does not apply well to implementation in a care pathway since they include over 300 diagnostic codes and do not take into account psychosocial factors.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) also developed by the WHO focuses on function [8]. The ICF describes function as “an umbrella term for body functions, body structures, activities and participation.” [18] The ICF is a general description of function that, if used in isolation, does not discuss a pathological diagnosis or intervention. To achieve this goal, it should be linked to ICD codes. The ICF and ICD are important in defining diagnoses and disability. However, these classification systems are complex, detailed and are difficult to use outside of a comprehensive high-resource health care setting with extensive administrative resources.

Several task forces have been convened to address spine conditions or symptoms, review the evidence for interventions, and make classification recommendations. The Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders divided neck pain into five groups [9]. This classification, however, only addressed whiplash injuries to the neck, mostly from motor vehicle crashes. The Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders recommended differentiating spine-related disorders into groups based on symptoms, clinical, and neurological findings [10]. It focuses on symptoms and pathology and requires the user to differentiate 11 classes, which mostly relate to pathology. The Bone and Joint Decade Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders used the Quebec Whiplash Classification system as a foundation and defined groups based on activity interference due to neck pain and the presence or absence of radiculopathy [17]. Serious pathology was defined as group IV in this classification, and conditions in this group were not addressed further. The National Institute of Health Back Pain Standards (NIHBPS) mirrors the criteria of the Neck Pain Task Force (NPTF) focusing on symptoms and disability for low back pain but, in addition, differentiated classes based on chronicity and severity of impact or impairment [12].

The NPTF and NIHBPS classification systems have been valuable in the discussion of the evidence for effectiveness of interventions and have led to more reasonable and logical approaches to patients, especially those with incapacitating low back and neck pain. These efforts have resulted in a greater focus on interventions that are supported by available evidence. They have stressed the importance of psychosocial factors and the reduction of the use of interventions with little supporting evidence. However, they address a limited number of symptoms such as low back, neck pain, or whiplash-associated symptoms. Therefore, they are not suitable for use in a setting that applies to people with spine symptoms or concerns irrespective of the nature of the symptom, spine region, severity, chronicity, and potential pathologies that a general spine care pathway needs to address.

Work-related disabilities were addressed in several classifications. The South Australia Work Cover Corporation Classification System was developed to determine legal impairment and focuses primarily on differentiating patients with non-specific pain from those with a pathological diagnosis [14]. The AMA Guide to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 5th edition is widely used in the USA as a means of establishing compensation for spine-related disability [19]. This system is based on clinical findings (e.g., muscle spasm or range of motion), the presence of radiculopathy, and loss of structural integrity. The 6th edition of the AMA Guides has similar goals but focuses on symptoms and impairment of activities caused by the symptoms [16]. These classification systems are used to determine legal impairment and should only be applied when a patient reaches the point of maximum medical improvement and therefore do not apply to people who are seeking care.

After deliberation, the panelists felt that any classification system should be compatible with survey instruments such as those developed by the Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health, so it would be relatively easy to translate the results of surveys into the implementation of a care pathway [20]. The classification panel recognized that none of the available and widely used classification systems presented above can guide clinicians to care for people who present with all possible forms of spine symptoms, concerns, or pathologies. It became evident that the panel needed to develop a comprehensive classification system to address all spine care concerns before a care pathway could be considered. The classification must include any person who might present to a spine program. The panel recognized that in some low-resource communities there may be presentations other than primary neck or low back pain, which may not be adequately addressed in the classic evidence-based guidelines that were established in high-income settings. In many global spine care programs, people may have concerns about minor irritating symptoms, prevention, and risk factors, but also pain that is in multiple spine regions, neurological symptoms and deformities, in addition to serious systemic pathology. Thus, the classification system must be created to address all presentations.

Seed document

Several meetings were held to refine the classification system. An initial draft that incorporated applicable principles of existing classification systems was presented to the GSCI workgroup. The participants wanted the classification to be compatible with other spine classification systems, relatively simple to use, and applicable to first-contact, health care specialties or professions. Refinements of the document were made through 4 round-table group discussions and multiple meetings among the executive and members of the classification panel. This process yielded an initial seed classification system (see Online Resource Figure 2).

Modified Delphi process

A modified Delphi process was performed to gain further input on the classification system and to obtain consensus from an interprofessional, international panel of spine care clinicians, researchers, and other stakeholders [21–23]. The modified Delphi process was selected because it allowed all participants to have an equal voice in the discussion and reduced the potential for bias or intimidation by senior researchers [21–23]. Throughout the process, comments were blinded so that the participants’ identities were not tied to comments when being reviewed by the principal investigators (SH, CJ). Comments were opened by the principal investigators only after all participants had responded. The participants gave informed consent that the GSCI research papers would be published with information including participant names, information from surveys/emails, and relevant conflict of interest information for purposes of transparency. Participants were given the right to refuse or withdraw without penalty at any time. This project was approved by National University of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (#H-1503). All participants were informed about the nature of the study and the modified Delphi process and gave written consent by completing the electronic questionnaire. Surveys were distributed using an online survey program (SurveyMonkey Inc, SurveyMonkey.com, San Mateo, California, USA).

The seed document was provided as the starting document. The first Delphi survey asked participants for their level of agreement on the overall classification, on each individual class, and gave the respondent the opportunity to provide comments. The first survey also included questions about demographics and their views and beliefs about health care. The first Delphi survey responses were collected and were matched to the relevant class. Each comment was considered and addressed by the GSCI Principal Investigators (SH, CJ) and the Executive Team (RC, PC, EH, MN) in a response report, which included recommended changes in the initial proposal with explanations and clarifications to address comments and concerns. Examples of patient presentations for each class were provided to clarify use of the classification (see supplemental file Appendix A).

All 43 participants from the first survey were invited to participate in the second round and were given the full response report in advance. The second Delphi survey asked participants to state their overall agreement, agreement with minor changes, or disagreement with the updated draft and to include any comments about the updated classification system. Consensus for the second survey was defined a priori as 80% agreement. The responses and comments were collected from the second survey. Since there was high agreement (95% of participants supported the updated classification), a third survey was not undertaken. Based upon feedback from the second survey, minor changes were made to the classification system, which included corrections to grammar and congruence. Following this, all participants were asked to review the manuscript draft, provide additional input, and invited to join as coauthors. (see Online Resource Figure 3 for the steps in the consensus process.)

Results

Invitations for the first modified Delphi survey were sent to 59 participants. Of the 59 invited, 14 (24%) did not reply or indicated that they did not wish to participate. Participants represented a wide variety of health and research disciplines and represented 15 countries (Australia, Botswana, Cameroon, Canada, Chile, Denmark, France, India, Iran, Kenya, Morocco, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, and USA).

In the first survey, several participants pointed out areas where they suggested a modification or expressed concerns. Concerns were addressed by modification to the seed document or with a response by the principal investigator. All comments were shared with all participants. The following is a summary of the primary concerns and explanations for modifications resulting from both survey rounds.

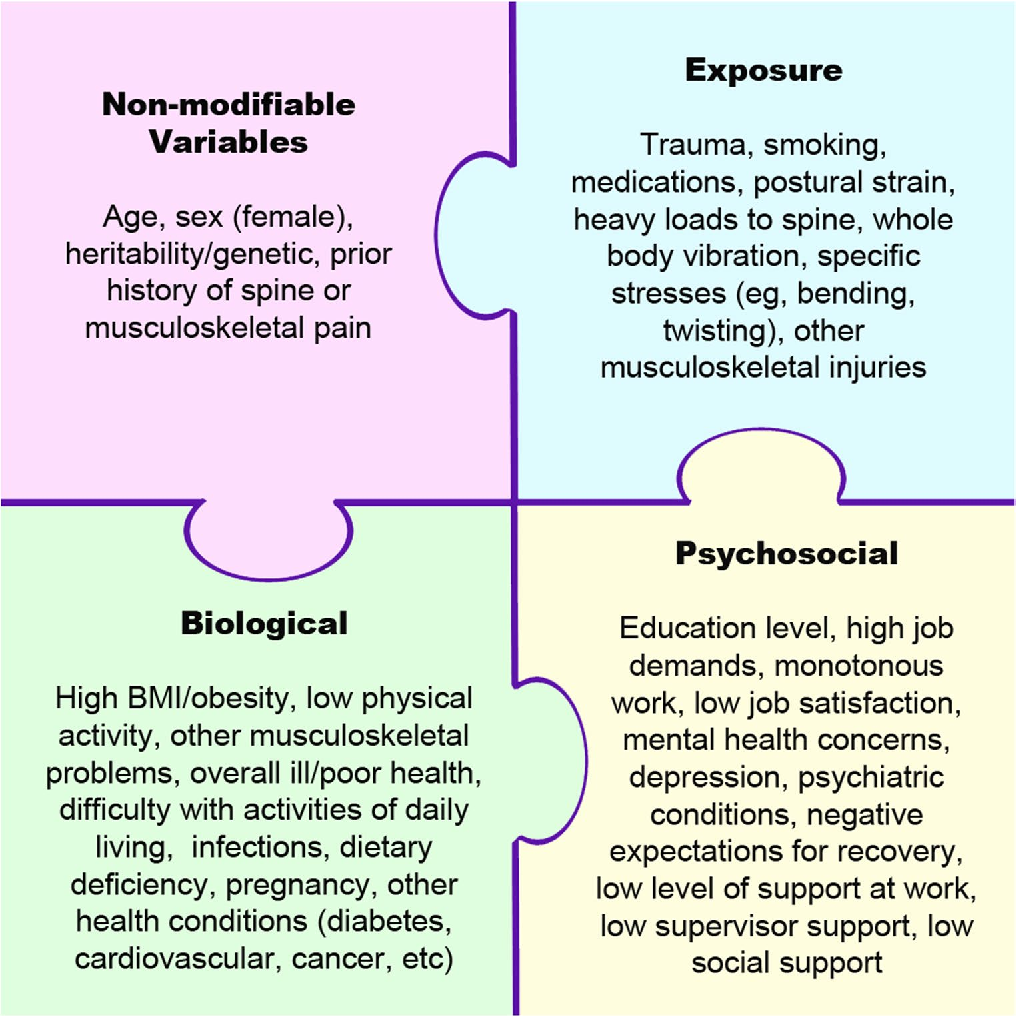

Summary of comments, responses, and modifications for each classClass 0 = no or minimal spine symptoms, may have risk factors In the second Delphi survey, a few participants questioned the purpose of this class. One person felt that a new classification system was not necessary and 2 expressed concern about the potential for over-medicalizing minor discomfort. Some spine care providers do not see people who have minimal pain, especially medical specialists who manage people with chronic and disabling pain. Clinicians in general practice see people with minor symptoms or concerns who either may seek advice for prevention or may be seeking care for another complaint. It was recommended that any model of care should include guidance on current evidence as defined in the GSCI papers concerning prevention including risk factors, comorbidities, and the importance of psychosocial concerns that could lead to over-medicalization [24–30].

Primary and secondary prevention measures, whether applied at a population or individual level, could potentially reduce further the burden of spine disorders when applied to the specific needs of any given community [28, 30]. These goals are consistent with WHO global strategy on integrated people-centered health services 2016–2026 that state “Reorienting the model of care … requires investment in holistic and comprehensive care, including health promotion and ill-health prevention strategies that support people’s health and well-being.” [31] For Class 0, we agreed that any of the classes could be considered as an option and that the health care provider may choose to use or not use any class depending on the social, or environmental situation, level of resources, or clinical setting in which they practice.

Class I = mild symptoms, no interference with function or activities of daily living, no neurologic deficits and Class II = moderate or severe symptoms, interference with function or activities of daily living, no neurologic deficits A few participants asked if there should be greater emphasis on diagnosis for Classes I and II, such as degeneration, discogenic pain, or muscle strain. Current evidence shows that findings from clinical examination (e.g., local tenderness, decreased range of motion) or radiographic imaging (e.g., degenerative findings) are common in asymptomatic people and do not have sufficient sensitivity and specificity to impact a decision concerning recommended interventions required in the development of a care pathway [29]. Therefore, specific diagnoses were not included in Class I or II.

Class III = neurological signs/symptoms originating from spinal pathology Participants discussed if Class III should have diagnostic subclasses that would accommodate diagnoses such as radiculopathy, myelopathy, or cauda equina syndrome. Participants agreed that this differentiation complicated the classification and that imaging and interventions would not vary markedly between these 3 diagnoses. However, interventions are different for patients with acute and progressive neurological deficits that may require emergency care or for those with chronic, stable or unchanging neurological symptoms. Therefore, the subcategories were modified to acute/mild, acute/progressive, and chronic/stable.

Class IV = severe spinal bone deformity, trauma, or pathology Some participants suggested the term “severe pathology” should have a more precise definition. There was also concern this class might be used by some people to justify surgical interventions for findings on imaging that have not been confirmed by the evidence to be a source of pain. The consensus was that Class IV differentiates the growing literature on the indications for spine surgery when welldefined spinal structural pathology, such as when congenital or developmental deformity, fracture, or disabling unstable spondylolisthesis are present [24, 32]. It was agreed that it is not the role of this classification system to define when surgical intervention is indicated. Instead, the GSCI systematic literature reviews and guidelines should be used to address the indications for surgery or other interventions.

Class V = spine*related symptoms associated with systemic or destructive pathology A few people questioned whether Class V was necessary. The Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders [9] and the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders [17] addressed this issue by calling all red flags for serious systemic pathology “Group IV” and elected not to make any recommendations for this group of patients. Not having this class may be reasonable in high-income settings where referral for advanced medical specialty care is readily available. However, in communities without these resources, spine care providers must triage a wide array of problems and make referral decisions. Therefore, the majority of participants agreed that guidance on presentations found in Class V should be included in a care pathway. This class helps to triage patients requiring care for acute emergency or life-threatening pathologies from those with chronic spine pathology that can be managed on a non-emergent basis. The inclusion of spinal symptoms originating from systemic, non-spinal tissues, and organ systems was questioned by a few participants, but the majority felt that this subclass was necessary to remind clinicians that not all spine-related symptoms originate from the spine and that these patients should be referred appropriately.GSCI spinal disorders classification

Table 2 We took all the ratings and comments into consideration and refined the classification by reducing the subclasses and rearranging the higher classes. The revision process after the first survey included the standardization of the taxonomy for each class, and a legend was added to help clarify terms [33]. The order of classes was rearranged and simplified to assist with use in the clinical setting. In the second survey, 95% of participants agreed with this statement “Do you agree that all possible presentations of a person to a spine clinician or clinic could be included in this classification system?” The final version of the GSCI classification is represented in Table 2. For examples of each class, see Online Resource Appendix A.

The GSCI classification system for spine-related concerns was then compared with the classes outlined in the review of other classifications. The comparison confirmed that the other broadly used classification systems could easily work in conjunction with the proposed GSCI classification system (see Online Resource Appendix B).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first interprofessional and international attempt to provide a comprehensive classification that reflects all potential presentations of people who may seek care or advice from a health care provider for spinerelated symptoms or concerns. The proposed classification system may be easily taught to clinicians and stakeholders, such as through visual educational tools (e.g., chart or flashcards), and may be easily adapted into electronic medical record software. This classification includes presentations of pain and disability, spine-related neurological symptoms, structural bony pathology, deformities, and serious systemic disease but, at the same time includes people who may benefit from primary or secondary prevention programs. Thus, this classification helps to fulfill the WHO strategies of reorienting models of care [31] to include all people who have or are at risk for specific health problems. This classification also accommodates a person who may present with multiple spine-related concerns. Therefore, a person with multiple concerns may be classified in more than one class (e.g., one class for neck pain and a different class for low back pain). If a patient presents with diffuse non-focal pain, the area would be noted and the classification compatible with its severity, chronicity, and functional interference would be assigned.

This classification was not developed to replace other spinal disorders classification systems. Instead, it incorporates most other attempts at categorizing spinal disorders and, at the same time, addresses all people with spine-related symptoms or concerns. Depending upon the social and environmental situation, level of resources, or clinical setting, any of the classes could be considered, included, or removed. Thus, it can be adapted to different environments in clinical, research, or policy development settings. A clinician or researcher who elects to follow the Quebec Whiplash or Bone and Joint Decade Task Force recommendations may choose to limit their consideration to Classes I, II, III and elect not to include the other classes or subclasses.

A clinician or researcher whose primary concern is non-specific low back pain may focus on the NIH Research Standards as noted in Classes I and II and include the subclasses addressing pain severity and chronicity. Surgical considerations would likely focus on patients in Classes III, IV, and V who might reasonably be considered candidates for surgery. A population-based primary prevention program would likely focus on Class 0. A rheumatologist or infectious disease specialist would likely focus on Class V presentations. The comprehensive spine care pathway could reasonably be implemented in communities with limited resources and therefore may incorporate the entire classification system. This classification allows for the determination of which individuals can reasonably be served at different levels of resources.

This spinal classification has language that can be used by any discipline and is simple enough to be easily taught to clinicians or stakeholders irrespective of their training or experience. The classification can differentiate people with spine-related symptoms that would likely require a different clinical decision or intervention pathway. Due to its design, it can match population needs where there are limited resources and therefore avoid over-medicalization of spine pain by avoiding the recommendation for a pathological diagnosis for most people who present with spine pain and disability but no red flags for serious pathology. Furthermore, it also accommodates the small number of people who may present with red flags for neurological deficits or serious pathology that may require emergency, surgical, or advanced pharmaceutical interventions.

The GSCI classification is consistent with most current survey and classifications systems. The classification has been informed by individuals participating in the modified Delphi processes as well as the systematic reviews and other articles being produced as part of the GSCI [1–6, 24–29, 32, 34]. It forms the basic framework for the GSCI care pathway and recommendations for implementation of a model of care. The classification is linked to systematic reviews of the scientific literature for public health, assessment, noninvasive as well as invasive interventions so that it may be useful in the clinical setting. The review of the evidence provides the basis for determining the indications and contraindications for each of the multiple interventions that may be considered for people who fall into one or more of these classifications.

The classification is flexible in that it can be used to address the entire spine or can be applied separately to different spine regions or pathological processes. An individual could be classified into one or more class at the same point in time. For example, a person could be in Class I for low back pain and Class II for neck pain. Therefore, a patient with a combination of spinal regions, symptoms, or pathological states may be accommodated in this classification.

This classification is person-centered and can accommodate individuals with spine symptoms that vary over time and have different levels of severity and chronicity. It allows an individual with spine symptoms to be assigned to more than one class; thus, classes are not mutually exclusive. The classification may be applied to a person entering or re-entering the system with symptoms suggestive of the same or a different class of spinal disorder, thus allowing for the realities of practice. At the same time, when matched with intervention guidelines and epidemiologic research it can be used by clinicians to inform their patients about diagnoses, intervention considerations, and prognoses. For the purposes of the GSCI, this document has informed the development of the care pathway and model of care.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this project include the large number of participants from multiple countries representing both highincome/ resource and low-income/resource communities. The participants represent a majority of scientific, policy, and clinical disciplines with an interest in spinal disorders. The number of comments after the first survey round and reaching 95% consensus after the second round confirms that the panelists were committed to the process. The fact that there were many comments and answers to the survey which were not in perfect agreement confirms that participants did not merely endorse opinions or recommendations of the principal investigators or executive team. Other strengths include that the classification is compatible with other available classification systems. It also has not been defined exclusively for clinical intervention purposes and can be used in research and policy development.

Limitations of this process were that 24% of the spine experts and patient advocates that we invited were not available to participate. Because they did not participate, the classification did not benefit from their input and if they had, the results may have been different. The list of participants did not include many lay people or patients who may have looked at this classification with different priorities. There was also no input from traditional or lay healers who are often the only health care practitioners in many communities. Some of these issues will be addressed in the readiness and implementation phases. This classification needs to be tested for validity, reliability, and consistency among clinicians from different specialties and in different communities and cultures.

Conclusion

This paper describes the first interprofessional and international attempt to provide a comprehensive classification for all potential presentations of people who may seek care or advice for spine-related symptoms or concerns. This classification system is sufficiently comprehensive to advise the development of a care pathway and sustainable model of care for spinal disorders. The classification system has been developed in a simplified manner so that it may be easily taught to clinicians and stakeholders. At present, the validity and reliability of the classification are not yet known. It will need to be field-tested to determine whether stakeholders, such as patients, policymakers, and clinicians in active practice, find it valuable.

Funding

The Global Spine Care Initiative and this study were funded by grants from the Skoll Foundation and NCMIC Foundation. World Spine Care provided financial management for this project. The funders had no role in study design, analysis, or preparation of this paper.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creat iveco mmons .org/licen ses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

References:

Hurwitz EL, Randhawa K, Yu H, Cote P, Haldeman S (2018)

The Global Spine Care Initiative: A Summary of the

Global Burden of Low Back and Neck Pain Studies

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 796–801Hurwitz EL, Randhawa K, Torres P, Yu H, Verville L, Hartvigsen J et al (2017)

The Global Spine Care Initiative: a systematic review of individual

and community-based burden of spinal disorders in rural

populations in low- and middle-income communities.

Eur Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5393-zHaldeman S, Nordin M, Chou R, Côté P, Hurwitz EL, Johnson CD, Randhawa K et al

The Global Spine Care Initiative: World Spine Care

Executive Summary on Reducing Spine-related Disability in

Low- and Middle-income Communities

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 776-785Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, Nordin M, Côté P, Hurwitz EL et al.

The Global Spine Care Initiative:

Care Pathway for People With Spine-related Concerns

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 901–914Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Chou R, Nordin M, Green BN, Côté P, Hurwitz EL et al (2018)

The Global Spine Care Initiative:

Model of Care and Implementation

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 925–945Kopansky-Giles D, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Chou R, Côté P, Green BN, Nordin M et al (2018)

The Global Spine Care Initiative:

Resources to Implement a Spine Care Program

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 915–924WHO (2004)

International statistical classification of diseases

and health related problems (The) ICD-10.

World Health Organization, GenevaWHO (2001)

International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF.

World Health Organization, GenevaSpitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, Cassidy JD, Duranceau J, Suissa S, Zeiss E.

Scientific Monograph of the Quebec Task Force on

Whiplash-Associated Disorders:

Redefining Whiplash and its Management

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 (Apr 15); 20 (8 Suppl): S1-S73Spitzer WO (1987)

Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-related spinal disorders.

A monograph for clinicians.

Report of the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders.

Spine 12(7 Suppl):S1–S59Guzman J, Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, et al.

Clinical Practice Implications of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010

Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders:

From Concepts and Findings to Recommendations

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S199–S212Deyo R, Dworkin S, Amtmann D, Andersson G, Partap Khalsa D, Loeser J et al (2013)

Report of the Task Force on Research.

Standards for chronic low-back pain.

National Institutes of Health, BethesdaR.A. Deyo, S.F. Dworkin, D. Amtmann, G. Andersson, et al.,

Report of the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for

Chronic Low Back Pain

Journal of Pain 2014 (Jun); 15 (6): 569–585Steven I (1993)

Guidelines for the management of back-injured employees.

South Australia Workcover Corporation, AdelaideDoege TC, Association AM, Houston TP (1993)

Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment.

Amer Medical Assn, ChicagoRondinelli RD, Genovese E, Brigham CR (2008)

Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment.

American Medical Association, ChicagoGuzman J, Haldeman S, Carroll LJ, et al.

Clinical Practice Implications of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010

Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders:

From Concepts and Findings to Recommendations

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S199–S212WHO (2013)

How to use the ICF. A practical manual for using the

international classification of functioning disability.

Health GenevaCocchiarella L, Andersson G, American Medical Association (2001)

Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment, 5th edn.

American Medical Association, Chicago, vol xxii, 613 ppDecade GAfMHotBaJ.

MSK Survey Module http://bjdonline.org/msk-survey-module/Dalkey NC (1967)

Delphi. RAND Corporation, Santa MonicaHsu C-C, Sandford BA (2007)

The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus.

Pract Assess Res Eval 12(10):1–8Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna HP (2001)

A critical review of the Delphi technique as a

research methodology for nursing.

Int J Nurs Stud 38(2):195–200Acaroglu E, Nordin M, Randhawa K, Chou R, Cote P, Mmopelwa T et al (2018)

The Global Spine Care Initiative: A Summary of Guidelines on

Invasive

Interventions for the Management of Persistent and Disabling

Spinal Pain in Low- and Middle-income Communities

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 870–878Ameis A, Randhawa K, Yu H, Cote P, Haldeman S, Chou R et al (2017)

The Global Spine Care Initiative: a review of reviews and recommendations

for the non-invasive management of acute osteoporotic vertebral compression

fracture pain in low- and middle-income communities

Eur Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5273-6Chou R, Baisden J, Carragee EJ, Resnick DK, Shaffer WO, Loeser JD (2009)

The Global Spine Care Initiative: A Narrative Review of Psychological

and Social Issues in Back Pain in Low- and Middle-income Communities

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 823–837Chou R, Cote P, Randhawa K, Torres P, Yu H, Nordin M et al (2017)

The Global Spine Care Initiative: Applying Evidence-based Guidelines

on the Non-invasive Management of Back and Neck Pain to Low-

and Middle-income Communities

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 851–860Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Kane EJ, Clay MB, Griffith E et al (2018)

The Global Spine Care Initiative: Public Health and Prevention Interventions

for Common Spine Disorders in Low- and Middle-income Communities

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 838–850Nordin M, Randhawa K, Torres P, Yu H, Haldeman S, Brady O et al (2018)

The Global Spine Care Initiative: A Systematic Review for the Assessment

of Spine-related Complaints in Populations with Limited Resources

and in Low- and Middle-income Communities

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 816–827Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Griffith E, Clay MB, Kane EJ et al (2018)

A Scoping Review of Biopsychosocial Risk Factors and

Co-morbidities for Common Spinal Disorders

PLoS One. 2018 (Jun 1); 13 (6) :e0197987Toro N (2015)

Who global strategy on integrated people-centred health services (IPCHS)/

Estrategia mundial en servicios de salud integrada centrado en las personas (IPCHS).

Int J Integr Care 15(8).

WCIC Conf Suppl; URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-117366Acaroglu E, Mmopelwa T, Yuksel S, Ayhan S, Nordin M, Randhawa K et al (2017)

The Global Spine Care Initiative: a consensus process to develop and

validate a stratification scheme for surgical care of spinal disorders

as a guide for improved resource utilization in low- and middle-income communities.

Eur Spine J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5332-zDeyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, Andersson G, Borenstein D, et al (2014)

Report of the National Institutes of Health task force on

earch standards for chronic low back pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Sep); 37 (7): 449-467Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Nordin M, Chou R, Côté P, Hurwitz EL et al (2018)

The Global Spine Care Initiative:

Methodology, Contributors, and Disclosures

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 786–795

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Return to GLOBAL BURDEN OF DISEASE

Since 5-08-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |