Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Noninvasive Management

of Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review by the Ontario

Protocol for Traffic Injury Management

(OPTIMa) CollaborationThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: European J Pain 2017 (Feb); 21 (2): 201–216 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS J.J. Wong, P. Côté, D.A. Sutton, K. Randhawa, H. Yu, S. Varatharajan, R. Goldgrub,

M. Nordin, D.P. Gross, H.M. Shearer, L.J. Carroll, P.J. Stern, A. Ameis,

D. Southerst, S. Mior, M. Stupar, T. Varatharajan, A. Taylor-Vaisey

UOIT-CMCC Centre for the Study of Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation,

University of Ontario Institute of Technology (UOIT) and

Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (CMCC),

Oshawa, ON, Canada.

jessica.wong@uoit.ca

BACKGROUND: Low back pain (LBP) is a major health problem, having a substantial effect on peoples' quality of life and placing a significant economic burden on healthcare systems and, more broadly, societies. Many interventions to alleviate LBP are available but their cost effectiveness is unclear.

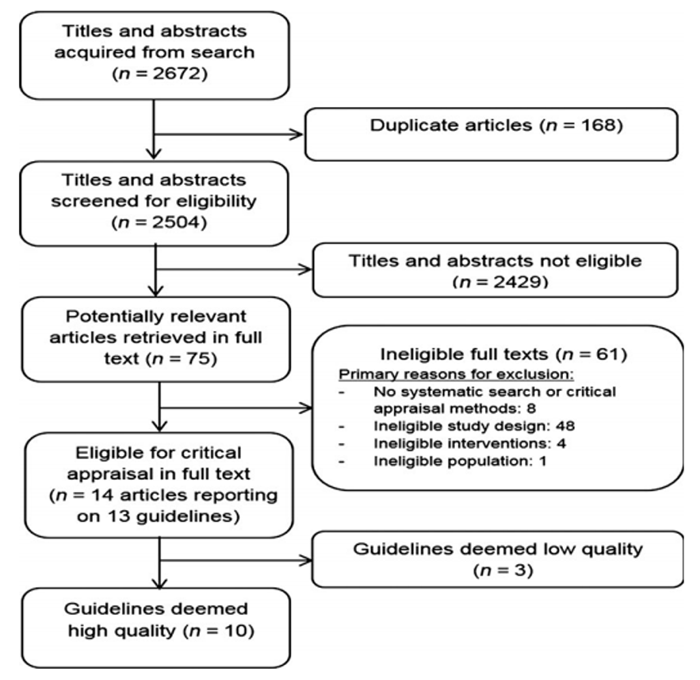

We conducted a systematic review of guidelines on the management of low back pain (LBP) to assess their methodological quality and guide care. We synthesized guidelines on the management of LBP published from 2005 to 2014 following best evidence synthesis principles. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane, DARE, National Health Services Economic Evaluation Database, Health Technology Assessment Database, Index to Chiropractic Literature and grey literature. Independent reviewers critically appraised eligible guidelines using AGREE II criteria. We screened 2504 citations; 13 guidelines were eligible for critical appraisal, and 10 had a low risk of bias.

According to high-quality guidelines:(1) all patients with acute or chronic LBP should receive education, reassurance and instruction on self-management options;

(2) patients with acute LBP should be encouraged to return to activity and may benefit from paracetamol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or spinal manipulation;

(3) the management of chronic LBP may include exercise, paracetamol or NSAIDs, manual therapy, acupuncture, and multimodal rehabilitation (combined physical and psychological treatment); and

(4) patients with lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy may benefit from spinal manipulation.Ten guidelines were of high methodological quality, but updating and some methodological improvements are needed. Overall, most guidelines target nonspecific LBP and recommend education, staying active/exercise, manual therapy, and paracetamol or NSAIDs as first-line treatments. The recommendation to use paracetamol for acute LBP is challenged by recent evidence and needs to be revisited.

SIGNIFICANCE: Most high-quality guidelines recommend education, staying active/exercise, manual therapy and paracetamol/NSAIDs as first-line treatments for LBP. Recommendation of paracetamol for acute LBP is challenged by recent evidence and needs updating.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

More than 80% of people experience at least one episode of back pain during their lifetime (Cassidy et al., 1998; Walker, 2000). Back pain is a common source of disability, whether the pain is attributed to work, traffic collisions, activities of daily living, or insidious onset (Cassidy et al., 1998, 2005; Hincapie et al., 2010). Back pain is costly, accounting for a considerable proportion of work absenteeism and lost productivity (Carey et al., 1995, 1996). Moreover, it is the most common reason for visiting a healthcare provider for musculoskeletal complaints (Cypress, 1983; Cote et al., 2001). Although multiple clinical interventions are available to treat back pain, current evidence suggests that their effects appear small and short term (Haldeman and Dagenais, 2008).

Clinical practice guidelines are systematically developed statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care and improve patients’ health outcomes (Shekelle et al., 1999, 2012; Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, 2011). Guidelines aim to reduce the gap between research and clinical practice and assist policy makers with decisions that impact the population (Whitworth, 2006; Alonso-Coello et al., 2010). However, concerns have been raised about the quality of many clinical practice guidelines (Ransohoff et al., 2013). Systematic reviews report that some guidelines have methodological limitations (Shaneyfelt et al., 1999; Graham et al., 2001; Hasenfeld and Shekelle, 2003; Alonso-Coello et al., 2010; Berrigan et al., 2011; Knai et al., 2012). Common flaws include poor literature review methodology, limited involvement of stakeholders and unclear editorial independence (Alonso-Coello et al., 2010). Therefore, valid concerns exist about the potentially negative impact of biased guidelines on the care and health outcomes of patients (DelgadoNoguera et al., 2009; Shaneyfelt and Centor, 2009; Tricoci et al., 2009; Alonso-Coello et al., 2010).

Guidelines of poor methodological quality may lead clinicians to consider interventions that are ineffective, costly, or harmful. Low-quality guidelines may lead decision makers to invest in the implementation of ill-informed recommendations. Moreover, low-quality guidelines may reduce their adoption by clinicians and policy makers. Known barriers to the adoption of guidelines include lack of clarity of recommendation development, ambiguous recommendations, and inconsistent recommendations across guidelines (Cote et al., 2009). Finally, when combined with other barriers, such as lack of time, limited understanding of how guidelines are developed, and inadequate dissemination, it is easy to understand why the uptake of some clinical guidelines by clinicians has been disappointing (Cote et al., 2009; Bishop et al., 2015; Slade et al., 2015).

Many clinical practice guidelines on the management of low back pain are available in the peerreviewed literature. A systematic review of these guidelines found that the quality of their methodology was adequate but varied across guidelines (Dagenais et al., 2010). However, the literature search for this systematic review ended in 2009 (Dagenais et al., 2010), and many guidelines have been published or updated since (Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2011; Brosseau et al., 2012; Delitto et al., 2012; Kung et al., 2012; North American Spine Society, 2012; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013; Kreiner et al., 2014). An up-to-date systematic review of these guidelines is needed to assess their methodological quality and help guide appropriate management of low back pain.

The purpose of this systematic review was to review clinical practice guidelines, programmes of care, and treatment protocols to identify effective conservative (noninvasive) interventions for the management of acute and chronic low back pain.

Methods

Review registration

The protocol for our systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42015017762) and can be accessed at www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_ record.asp?ID=CRD42015017762.

Literature search

We developed the search strategy in consultation with a health sciences librarian. A second librarian reviewed the search strategy using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies Checklist (Sampson et al., 2009). The search strategy combined terms relevant to low back pain and guidelines and included free-text words and subject headings specific to each database (Supporting Information Appendix S1). The following databases were searched from January 1, 2005, to April 30, 2014: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, National Health Services Economic Evaluation Database, Health Technology Assessment Database and the Index to Chiropractic Literature. Guidelines published prior to 2005 were considered outdated (Kung et al., 2012) and were captured in a previous systematic review of guidelines (Dagenais et al., 2010). We hand searched reference lists of relevant guidelines for supplemental documents relevant to the methodology of that guideline.

We searched the grey literature using the following: National Guideline Clearinghouse (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality), Canadian Medical Association Infobase, Guidelines International Network, PEDro, Trip Database, American College of Physicians Clinical Recommendations, Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council, Health Services/Technology Assessment Texts, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Guidance, NICE Pathways, New Zealand Guidelines Group, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), and World Health Organization guidelines approved by the Guidelines Review Committee.

Study selection

We used the following inclusion criteria:(1) English language;

(2) targeting adults and/or children with low back pain with or without radiculopathy;

(3) J.J. Wong et al. Clinical practice guidelines for low back pain management guidelines, programmes of care, or treatment protocols;

(4) including recommendations for therapeutic noninvasive management.

We excluded guidelines that:(1) did not include treatment recommendations;

(2) were a summary or copy of previous guidelines;

(3) were developed solely on the basis of consensus opinion;

(4) did not conduct a systematic literature search or critical appraisal of studies used to derive recommendations; and

(5) only targeted invasive (e.g. injection, surgery) interventions.Title and abstract screening

We used a two-stage (title/abstracts and full-text) screening process with random pairs of independent reviewers. Disagreements between pairs of reviewers were resolved by discussion. A third reviewer was used to resolve disagreements if consensus could not be reached. We contacted authors if additional information was necessary to determine eligibility.

Critical appraisal of eligible guidelines

Randomly allocated pairs of independent reviewers appraised relevant guidelines using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument (Table 1; Brouwers et al., 2010). The AGREE II instrument is widely used to assess the development and reporting of guidelines. It consists of 23 items in six quality-related domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence of guidelines (Table 1). All reviewers were trained in critical appraisal of guidelines using the AGREE II instrument. Discussions were held between paired reviewers to reach consensus on:(1) individual AGREE II items;

(2) overall guideline quality;

(3) whether the guideline was high quality; and

(4) whether modifications to the guideline would be needed for use in specific jurisdictions (e.g. updating literature, modifying the format of the guideline). We contacted authors if additional information was needed to complete the critical appraisal.Guidelines with poorly conducted systematic literature searches (question 7 of AGREE II) or with inadequate methods to critically appraise the evidence (question 9 of AGREE II) were deemed to have fatal flaws and were excluded from our synthesis. These criteria are described as fundamental steps to the development of evidence-based guidelines (Ransohoff, 2013). Although not considered a fatal flaw, we considered lack of editorial independence from the funding body (question 22 of AGREE II) an important limitation to the quality of the guideline. The absence of editorial independence would contribute to lower overall guideline quality, since this may suggest poor reporting and lack of transparency in guideline development (Alonso-Coello et al., 2010).

Data extraction

One reviewer extracted data from high-quality guidelines and built evidence tables. A second reviewer checked the data that were extracted from each guideline by comparing the extracted data with the data reported in the guidelines. We did not extract data on the use of interventional (invasive, surgical) therapies.

Data synthesis

We synthesized recommendations from high-quality guidelines using evidence tables. Recommendations from high-quality guidelines were synthesized by interventions and summarized according to whether an intervention is(1) recommended;

(2) not recommended or

(3) lacked evidence to support or refute its use.We considered an intervention to be ‘recommended’ if the high-quality guideline used the following terminology: ‘strongly recommended’, ‘recommended without any conditions required’, ‘should be used’, or ‘recommended for consideration’ [includes ‘offer’ or ‘consider’ (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2014)]. We stratified recommendations by duration of low back pain (i.e., acute or chronic) and by the number of guidelines recommending the intervention (‘recommended by all guidelines’ or ‘recommended by most guidelines’, i.e., more than 50% of guidelines).

Results

Figure 1 We screened 2504 titles and abstracts for eligibility (Figure 1). Of those, 75 potentially relevant articles were assessed in full-text screening and 61 were ineligible. Primary reasons for ineligibility during full-text screening were

(1) no systematic search or critical appraisal methods (8/61);

(2) ineligible study design (48/61);

(3) ineligible interventions (4/61); and

(4) ineligible population (1/61).We critically appraised 13 eligible guidelines (reported in 14 articles/publications) and needed to contact authors of five guidelines (3/5 responded) to obtain additional information to assess guideline quality (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Livingston et al., 2011).

We identified 10 high-quality guidelinesAiraksinen et al., 2006;

Nielens et al., 2006;

van Tulder et al., 2006;

Chou et al., 2007;

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009;

Cutforth et al., 2011;

Livingston et al., 2011;

Delitto et al., J.J. Wong et al. Clinical practice guidelines for low back pain management 2012;

North American Spine Society, 2012;

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013;

Kreiner et al., 2014.Inter-rater agreement for article screening was k = 0.66 (95% confidence intervals 0.51; 0.81). Percentage agreement for guideline admissibility during independent critical appraisal was 77% (10/13). We reached consensus through discussion for the three guidelines where there was disagreement between reviewers’ independent appraisal review (Livingston et al., 2011; Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2011; Brosseau et al., 2012).

1. Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the 13 relevant guidelines varied (Tables 2 and 3). Most guidelines did not adequately address guideline applicability, particularly facilitators and barriers, resource implication, and/or monitoring or auditing criteria upon implementation (8/13 guidelines; Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007, 2009; Livingston et al., 2011; Brosseau et al., 2012; Delitto et al., 2012; Kreiner et al., 2014). Similarly, most guidelines did not clearly indicate whether they sought the views or preferences of the target population (9/13 guidelines; Airaksinen et al., 2006; van Tulder et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Brosseau et al., 2012; Delitto et al., 2012; Kreiner et al., 2014).

The 10 guidelines with high methodological quality met the following criteria:(1) systematic methods to search for evidence (10/10);

(2) clearly described strengths and limitations of the evidence (10/10);

(3) considered health benefits, side-effects and risks (10/ 10);

(4) provided an explicit link between recommendations and supporting evidence (10/10);

(5) clearly described methods for formulating recommendations (9/10); and (6) clearly described criteria for selecting evidence (7/10; Tables 2).However, the high-quality guidelines had limitations, including

(1) no description of an external review process (5/10) (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; van Tulder et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; Livingston et al., 2011);

(2) no description of the procedure to update the guideline (3/10) (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; van Tulder et al., 2006); or

(3) no declaration of competing interests by the guideline development group (2/10) (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Livingston et al., 2011).Six guidelines were published more than 5 years ago and need to be updated (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; van Tulder et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007, 2009; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009).

The three low-quality guidelines had major limitations:(1) no clear selection criteria of the literature (2/3; Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2011; Delitto et al., 2012);

(2) no clear description of strengths and limitations of the literature (2/3; Brosseau et al., 2012; Delitto et al., 2012);

(3) no clear description of the methods used to formulate recommendations (3/3; Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2011; Brosseau et al., 2012; Delitto et al., 2012);

(4) no description of side-effects and risks (2/3; Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2011; Brosseau et al., 2012);

(5) no description of editorial independence from funders (1/3; Delitto et al., 2012); and

(6) no declaration of whether there were any competing interests by guideline development group (3/3; Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2011; Brosseau et al., 2012; Delitto et al., 2012).2. High-quality guidelines

Nine of the 10 high-quality guidelines addressed nonspecific low back pain (Table S1 and Tables 4). Of these, one guideline targeted acute low back pain (van Tulder et al., 2006), five targeted chronic low back pain (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2009; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013), and three addressed both acute and chronic (Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011). For chronic low back pain, one guideline commented on multimodal rehabilitation (combined physical and psychological interventions) only (i.e., no recommendations for any other noninvasive interventions; Chou et al., 2009). The remaining guideline targeted lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy (Table S1 and Table 4; Kreiner et al., 2014).3. Acute nonspecific low back pain (four high-quality guidelines)

Interventions recommended by all guidelines:(1) Advice, reassurance, or education with evidencebased information on expected course of recovery and effective self-care options for pain management (van Tulder et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011).

(2) Early return to activities, staying active, or avoiding prescribed bed rest (van Tulder et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011).

(3) Paracetamol (acetaminophen) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if indicated (van Tulder et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011), with advice and consideration of risks and warning symptoms and signs associated with these medications. Only one guideline specified the recommended type and dosage of NSAID use [i.e. Ibuprofen, up to 800 mg three times per day (maximum of 800 mg four times per day) or diclofenac, up to 50 mg three times per day] (Cutforth et al., 2011).

(4) Muscle relaxants (short course) alone or in addition to NSAIDs if an initial trial of paracetamol or NSAIDs failed to reduce pain on their own (van Tulder et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011), with advice and consideration of sedation risks associated with muscle relaxants (Chou et al., 2007; Livingston et al., 2011). Only one guideline specified the recommended type and dosage of muscle relaxant use (i.e. Cyclobenzaprine, 10– 30 mg/day, with greatest benefit within 1 week, although up to 2 weeks may be justified) (Cutforth et al., 2011).

(5) Spinal manipulation for those not improving with self-care options (Chou et al., 2007; Livingston et al., 2011) or failing to return to normal activities (van Tulder et al., 2006; Cutforth et al., 2011).

Interventions recommended by most guidelines:(1) Short-term use of opioids on rare occasions, to control refractory, severe pain (3/4 guidelines) (Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011). However, long-term use of opioids may be associated with significant risks related to the potential for tolerance, addiction or abuse (Livingston et al., 2011). One guideline did not address opioids for acute low back pain (van Tulder et al., 2006).

4. Chronic nonspecific low back pain (eight high-quality guidelines)

Interventions recommended by all guidelines:(1) Education including advice and information promoting self-management (Cutforth et al., 2011); evidence-based information on expected course and effective self-care options (Chou et al., 2007; Livingston et al., 2011); brief educational interventions for short-term improvement (Airaksinen et al., 2006); and advice to stay active or make an early return to activities as tolerated (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013).

(2) Exercises (Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013) including supervised exercises (Airaksinen et al., 2006; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009) or yoga (Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011). Three guidelines found insufficient evidence to make recommendations for or against any specific type of exercise (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013), but to instead consider patient preferences (Airaksinen et al., 2006). Recommended frequency/duration was a maximum of eight sessions over up to 12 weeks (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009).

(3) Manual therapy, including spinal manipulation (Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011) or mobilizations (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006). Recommended treatment frequency/duration was a maximum of nine sessions over up to 12 weeks (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009).

(4) Paracetamol or NSAIDs as therapeutic options while considering side-effects and patient preferences (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013).

(5) Short-term use of opioids when paracetamol or NSAIDs provided insufficient pain relief (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013). However, it is important to take into account side-effects, risks, and patient preference (Chou et al., 2007; Livingston et al., 2009; Livingston et al., 2011; Nielens et al., 2006) and to continue only with regular re-assessments and when there is evidence of ongoing pain relief (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013).

(6) Multimodal rehabilitation that included physical and psychological interventions (e.g., cognitive/ behavioural approaches and exercise) for patients with high levels of disability or signifi- cant distress (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007, 2009; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013). Recommended treatment frequency/duration was around 100 h over a maximum of up to 8 weeks (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009).Interventions recommended by most guidelines:

(1) Massage (Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Nielens et al., 2006; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013); however, one guideline recommended against massage for chronic low back pain (Airaksinen et al., 2006). This difference is likely due to more recent evidence informing the newer guidelines’ recommendations (Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013).

(2) Acupuncture (Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013); however, one guideline recommended against acupuncture (Airaksinen et al., 2006). Again, this difference is likely due to more recent evidence informing the newer guidelines’ recommendations (Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2009; Livingston et al., 2011; Nielens et al., 2006; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013). Recommended treatment frequency/duration was a maximum of 10 sessions over up to 12 weeks (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009).

(3) Antidepressants as an option for pain relief, but possible side-effects (drowsiness, anticholinergic effects) should be considered (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011). However, one guideline recommended that antidepressants should not be used for chronic low back pain (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013), while one guideline reported conflicting evidence on the effectiveness of antidepressants (Nielens et al., 2006).

Interventions not recommended by most guidelines:(1) Muscle relaxants (Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013); six guidelines made recommendations on the use of muscle relaxants (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013). Of those, four recommended against its use (Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013) and two stated that muscle relaxants can be considered as an option for pain relief (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006). Specifically, one guideline reported that the benefit of muscle relaxants could not be estimated due to low-quality evidence (Chou et al., 2007). Two guidelines reported that some muscle relaxants (cyclobenzaprine, benzodiazepines) may provide short-term pain relief, but cautioned against long-term use due to side-effects (drowsiness, dizziness, addiction, allergic sideeffects, reversible reduction of liver function, gastrointestinal effects) (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006). However, evidence on the effectiveness of muscle relaxants was conflicting (Nielens et al., 2006). One guideline did not address muscle relaxants (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009).

(2) Gabapentin (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; Cutforth et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013); one guideline found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against gabapentin for chronic low back pain (Chou et al., 2007). Two guidelines did not address gabapentin (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Livingston et al., 2011). Two guidelines recommended considering gabapentin for neuropathic pain (but not chronic low back pain) (Cutforth et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013).

(3) Passive modalities (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Nielens et al., 2006), including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), laser, interferential therapy or ultrasound (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Nielens et al., 2006). Two guidelines found insufficient evidence for or against laser (Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011) or interferential therapy (Chou et al., 2007). One guideline did not address passive modalities (Livingston et al., 2011). One guideline recommended that laser could be considered a treatment option based on inconsistent evidence (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013).

Lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy (one high-quality guideline)

One high-quality guideline made recommendations for the noninvasive management of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy (Kreiner et al., 2014). Five other high-quality guidelines (Airaksinen et al., 2006; van Tulder et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007, 2009; Livingston et al., 2011) included low back pain with leg pain in their scope, but did not have specific recommendations for the noninvasive management of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy.

Recommended interventions:(1) Spinal manipulation may be an option for symptomatic relief (Kreiner et al., 2014).

(2) A limited course of structured exercise for patients with mild to moderate symptoms. This option was based on the consensus opinion of the guideline development group (in the absence of reliable evidence; Kreiner et al., 2014).

There was insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for or against the use of traction, ultrasound, and low-level laser therapy (Kreiner et al., 2014).

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines to identify effective conservative (noninvasive) interventions for the management of acute and chronic low back pain. Most recommended interventions provide time-limited and small bene- fits. Based on high-quality guidelines:(1) patients with low back pain should be provided with education and encouraged to stay active and return-toactivity as tolerated; and

(2) the management of acute nonspecific low back pain includes spinal manipulation (when not improving with self-care or not returning to normal activities), paracetamol or NSAIDs as indicated.Based on high-quality guidelines, the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain includes the following:

(1) paracetamol or NSAIDs (although the effectiveness of paracetamol is now being challenged by new evidence);

(2) shortterm use of opioids for relief of refractory, severe pain;

(3) exercises;

(4) manual therapy;

(5) acupuncture, and

(6) multimodal rehabilitation (combined physical and psychological treatment).Finally, the noninvasive management of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy may include spinal manipulation for symptomatic relief (Kreiner et al., 2014). Very few guidelines provided information on recommended dose and frequency of care.

Our results agree with recommended interventions identified by a previous systematic review of guidelines on low back pain (Dagenais et al., 2010). We confirmed that most passive modalities (e.g. TENS, laser, ultrasound) are not recommended for managing chronic low back pain (Dagenais et al., 2010). In addition, we found one recent high-quality guideline on lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy published in 2012 (North American Spine Society, 2012).

However, the recommendation of paracetamol for acute low back pain is challenged by a recent highquality randomized controlled trial, which found that paracetamol did not improve recovery time compared with placebo for acute low back pain (Williams et al., 2014). Previous systematic reviews found no evidence supporting paracetamol for low back pain (Davies et al., 2008; Machado et al., 2015). Moreover, some high-quality guidelines used evidence from other conditions (e.g., osteoarthritis) to inform recommended interventions [paracetamol (Chou et al., 2007; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011) or opioids (Deyo et al., 2015)] for acute low back pain. Therefore, it is possible that using evidence for the management of other conditions, even if clinically relevant, may lead to inadequate recommendations. Given the risk of adverse events, we should reconsider the universal endorsement of paracetamol for the management of low back pain (Williams et al., 2014; Machado et al., 2015). This emphasizes that guidelines must be updated every 5 years to ensure that the most up-to-date evidence is used to inform clinical recommendations (Kung et al., 2012).

We found that high-quality guidelines lacked details about the use of acupuncture for the management of low back pain (Nielens et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013). This is important because it is known that different acupuncture techniques have different levels of effectiveness (Furlan et al., 2005). Future guidelines should consider stratifying evidence by acupuncture technique and provide clear details about the parameters for acupuncture use in patients with low back pain.

Clinical practice guidelines of low methodological quality are still being developed and published (Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2011; Brosseau et al., 2012; Delitto et al., 2012). These guidelines typically fail to: (1) clearly outline selection criteria of the literature; (2) adequately describe strengths and limitations of the literature and (3) adequately describe the methods used to formulate recommendations (Ransohoff et al., 2013). Our review highlights that the next generation of high-quality guidelines must focus on applicability to specific populations and clear implementation strategies to promote adherence. Nine of 13 eligible guidelines did not adequately address the AGREE II applicability criteria. Recent evidence suggests that favourable health and economic outcomes could be achieved if evidenceinformed decision making is used to manage low back pain (Kosloff et al., 2013). However, current clinical practice is ineffective in adhering to evidence-based guideline recommendations (Kosloff et al., 2013).

Future guidelines need to integrate the views and preferences of the target population (patients, public) into guideline development. Nine of 13 eligible guidelines did not mention whether these views and preferences were sought (Airaksinen et al., 2006; van Tulder et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2007, 2009; Cutforth et al., 2011; Livingston et al., 2011; Brosseau et al., 2012; Delitto et al., 2012; Kreiner et al., 2014). Integrating patient preferences into the guideline development process: (1) improves uptake and real-world efficiency of recommended healthcare interventions; (2) enhances consumer empowerment, and (3) informs individual patient preferences in clinical decision making (Dirksen et al., 2013; Dirksen, 2014).

The recommendations included in clinical practice guidelines typically involve the consensus of guideline expert panels who are asked to consider decision determinants, such as overall clinical benefit (effectiveness and safety), value for money (cost-effectiveness), consistency with expected societal and ethical values, and feasibility of adoption into the health system (Johnson et al., 2009). The scientific evidence serves as the foundation from which recommendations are built. Therefore, significant limitations are associated with recommendations solely developed using clinical opinions. Assembling, evaluation, and summarizing of evidence are fundamental aspects of guideline development, including a systematic review and assessment of the quality of evidence (Ransohoff et al., 2013). Recommendations based solely on opinion may be liable to biases and conflicts of interest or may not benefit patients (especially when patients’ views are not considered during guideline development).

Strengths and limitations

Our review had strengths. The literature search was comprehensive, methodologically rigorous, and checked by a second librarian. We outlined detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria to identify relevant evidence-based guidelines. Pairs of independent, trained reviewers screened and critically appraised the literature. This review used a recommended critical appraisal instrument for evaluating guidelines to maintain high methodological rigour (Brouwers et al., 2010). Some guidelines lacked methodological details, and we made multiple attempts to contact authors so that our screening and critical appraisal was as accurate as possible.

The main limitation was the restriction of guidelines published in English. Most guidelines are published in the language of the target users (e.g., Haute Autorite de Sante in France or El Instituto Aragones de Ciencas de la Salud in Spain) (El Instituto Aragones de Ciencas de la Salud, 2016; Haute Autorite de Sante, 2016). It is possible that excluding guidelines published in a language other than English may have biased our results. However, it is unclear whether recommendations that are not published in English would differ from those published in English. Finally, the external validity of our results may be limited to users from English-speaking jurisdictions. A second limitation concerns the definitions used to classify acute and chronic low back pain, which varied across guidelines. Four guidelines defined chronic low back pain as pain lasting more than 3 months (Airaksinen et al., 2006; Nielens et al., 2006; van Tulder et al., 2006; Cutforth et al., 2011). Three guidelines grouped recommendations for subacute and chronic low back pain into one category (Chou et al., 2007; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009; Livingston et al., 2011). Of those, two guidelines defined subacute/chronic low back pain as pain lasting more than 4 weeks (Chou et al., 2007; Livingston et al., 2011), and one guideline defined persistent low back pain as pain lasting more than 6 weeks (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2009). Finally, two guidelines did not provide a clear definition of chronic low back pain (Chou et al., 2009; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2013). The different classifications used to make recommendations for the management of low back pain complicate the evidence synthesis and may have led to the misclassification of recommendations.

Conclusions

Most high-quality guidelines target the noninvasive management of nonspecific low back pain and recommend education, staying active/exercise, manual therapy, and paracetamol or NSAIDs as first-line treatments. However, the endorsement of paracetamol for acute low back pain is challenged by a recent high-quality randomized controlled trial and systematic review; therefore, guidelines need updating. Some high-quality guidelines used evidence from other conditions to inform recommendations, which can lead to inadequate recommendations. Most eligible guidelines poorly addressed the applicability and implementation of recommendations. Finally, guideline developers need to involve end users during guideline development.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Carlo Ammendolia, J. David Cassidy, Gail Lindsay, John Stapleton, Leslie Verville, Michel Lacerte, Mike Paulden, Patrick Loisel, and Roger Salhany for their invaluable contributions to this review. The authors also thank Trish Johns-Wilson at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology for her review of the search strategy.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

References:

Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al.

COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain Chapter 4.

European Guidelines for the Management of

Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain

European Spine Journal 2006 (Mar); 15 Suppl 2: S192–300Alonso-Coello, P., Irfan, A., Sola, I., Gich, I., Delgado-Noguera, M., Rigau, D. (2010).

The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades:

A systematic review of guideline appraisal studies.

Qual Saf Health Care 19, e58.Berrigan, L., Marshall, S., McCullagh, S., Velikonja, D., Bayley, M. (2011).

Quality of clinical practice guidelines for persons

who have sustained mild traumatic brain injury.

Brain Inj 25, 742–751.Bishop, F.L., Dima, A.L., Ngui, J., Little, P., Moss-Morris, R., Foster, N.E. (2015).

“Lovely Pie in the Sky Plans”: A qualitative study of clinicians’ perspectives

on guidelines for managing low back pain in primary care in England.

Spine 40, 1842–1850.Brosseau, L., Wells, G.A., Poitras, S., Tugwell, P., Casimiro, L., Novikov, M. (2012).

Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines

on therapeutic massage for low back pain.

J Bodyw Mov Ther 16, 424–455.Brouwers, M.C., Kho, M.E., Browman, G.P., Burgers, J.S., Cluzeau, F. (2010).

AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting

and evaluation in health care.

CMAJ 182, E839–E842.Carey, T.S., Evans, A., Hadler, N., Kalsbeek, W., McLaughlin, C. (1995).

Care-seeking among individuals with chronic low back pain.

Spine 20, 312–317.Carey, T.S., Evans, A.T., Hadler, N.M., Lieberman, G., Kalsbeek, W.D., Jackman, A.M. (1996).

Acute severe low back pain. A population-based study

of prevalence and care-seeking.

Spine 21, 339–344.Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L.

The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey. The Prevalence of

Neck Pain and Related Disability in Saskatchewan Adults

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 (Aug 1); 23 (15): 1689–1698Cassidy, J.D., Cote, P., Carroll, L.J., Kristman, V. (2005).

Incidence and course of low back pain episodes in the general population.

Spine 30, 2817–2823.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr., Shekelle P, Owens DK:

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical

Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians

and the American Pain Society

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 478–491Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, Rosenquist RW, Atlas SJ, Baisden J, et al.

Interventional Therapies, Surgery, and Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation

for Low Back Pain: An Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline

From the American Pain Society

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009 (May 1); 34 (10): 1066–1077Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L.

The Treatment of Neck and Low Back Pain:

Seeks Care? Who Goes Where?

Med Care. 2001 (Sep); 39 (9): 956–967Cote, A.M., Durand, M.J., Tousignant, M., Poitras, S. (2009).

Physiotherapists and use of low back pain guidelines:

A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators.

J Occup Rehabil 19, 94–105.Cutforth, G., Peter, A., Taenzer, P. (2011).

The Alberta health technology assessment (HTA) ambassador program:

The development of a contextually relevant, multidisciplinary clinical

practice guideline for non-specific low back pain: A review.

Physiother Can 63, 278–286.Cypress, B.K. (1983).

Characteristics of physician visits for back symptoms:

A national perspective.

Am J Public Health 73, 389–395.Dagenais S, Tricco AC, Haldeman S.

Synthesis of Recommendations for the Assessment and Management

of Low Back Pain From Recent Clinical Practice Guidelines

Spine J. 2010 (Jun); 10 (6): 514–529Davies, R.A., Maher, C.G., Hancock, M.J. (2008).

A systematic review of paracetamol for non-specific low back pain.

Eur Spine J 17, 1423–1430.Delgado-Noguera, M., Tort, S., Bonfill, X., Gich, I., Alonso-Coello, P. (2009).

Quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines for the prevention

and treatment of childhood overweight and obesity.

Eur J Pediatr 168, 789–799.Delitto, A., George, S.Z., Van Dillen, L.R., Whitman, J.M., Sowa, G., Shekelle, P. (2012).

Low Back Pain: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International

Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic

Section of the American Physical Therapy Association

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2012; 42 (4): A1–A57Deyo, R.A., Von Korff, M., Duhrkoop, D. (2015).

Opioids for low back pain.

BMJ 350, g6380.Dirksen, C.D. (2014).

The use of research evidence on patient preferences in health care

decision-making: Issues, controversies and moving forward.

Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 14, 785–794.Dirksen, C.D., Utens, C.M., Joore, M.A., van Barneveld, T.A., Boer, B., Dreesens, D.H., van Laarhoven, H., Smit, C., Stiggelbout, A.M., van der Weijden, T. (2013).

Integrating evidence on patient preferences in healthcare

policy decisions: Protocol of the patient-VIP study.

Implement Sci 8, 64.El Instituto Aragones de Ciencas de la Salud (2016).

El Instituto Aragones de Ciencas de la Salud Gu?as de Practica Cl?nica.Furlan, A.D., van Tulder, M., Cherkin, D., Tsukayama, H., Lao, L. (2005).

Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain: An updated

systematic review within the framework of

the Cochrane collaboration.

Spine 30, 944–963.Graham, I.D., Beardall, S., Carter, A.O., Glennie, J., Hebert, P.C. (2001).

What is the quality of drug therapy clinical

practice guidelines in Canada?

CMAJ 165, 157–163.Haldeman S, Dagenais S.

A Supermarket Approach to the Evidence-informed

Management of Chronic Low Back Pain

Spine Journal 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 1–7Hasenfeld, R.S., Shekelle, P.G. (2003).

Is the methodological quality of guidelines declining in the US?

Comparison of the quality of US Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research (AHCPR) guidelines with those published subsequently.

Qual Saf Health Care 12, 428–434.Haute Autorite de Sante (2016).

Haute Autorite de Sante Elaboration de recommandations de bonne

pratique: Methode recommandations pour la pratique clinique.Hincapie, C.A., Cassidy, J.D., Cote, P., Carroll, L.J., Guzman, J. (2010).

Whiplash injury is more than neck pain: A population-based

study of pain localization after traffic injury.

J Occup Environ Med 52, 434–440.Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines (2011).

Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust.

R. Graham, M. Mancher, D. Miller Wolman, S. Greenfield, and E. Steinberg, eds

(Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US)).Johnson, A.P., Sikich, N.J., Evans, G., Evans, W., Giacomini, M., Glendining, M. (2009).

Health technology assessment: A comprehensive framework for

evidence-based recommendations in Ontario.

Int J Technol Assess Health Care 25, 141–150.Knai, C., Brusamento, S., Legido-Quigley, H., Saliba, V., Panteli, D. (2012).

Systematic review of the methodological quality of clinical guideline

development for the management of chronic disease in Europe.

Health Policy 107, 157–167.Kosloff TM, Elton D, Shulman SA, et al.

Conservative Spine Care: Opportunities to Improve the Quality

and Value of Care

Popul Health Manag. 2013 (Dec); 16 (6): 390–396Kreiner, D.S., Hwang, S.W., Easa, J.E., Resnick, D.K., Baisden, J.L. (2014).

An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and

treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy.

Spine J 14, 180–191.Kung, J., Miller, R.R., Mackowiak, P.A. (2012).

Failure of clinical practice guidelines to meet Institute of Medicine standards:

Two more decades of little, if any, progress.

Arch Intern Med 172, 1628–1633.Livingston, C., King, V., Little, A., Pettinari, C., Thielke, A. (2011).

Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines Project.

Evaluation and Management of Low Back Pain: PDF

A Clinical Practice Guideline Based on the Joint Practice Guideline

of the American College of Physicians and the

American Pain Society

(Salem, Oregon: Office for Oregon Health Policy and Research).Machado, G.C., Maher, C.G., Ferreira, P.H., Pinheiro, M.B., Lin, C.W. (2015).

Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis:

Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials.

BMJ 350, h1225.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).

Low Back Pain: Early Management of Persistent Nonspecific Low Back Pain PDF

London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2009.

[Report No.: Clinical guideline 88].National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (2014).

NICE Guidance.Nielens, H., Van Zundert, J., Mairiaux, P., Gailly, J., Van Den Hecke, H. (2006).

Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre.

Chronic Low Back Pain (KCE Report).North American Spine Society (2012).

Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation With Radiculopathy PDF

(Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine (2011).

Low back pain management guideline.Ransohoff, D.F., Pignone, M., Sox, H.C. (2013).

How to decide whether a clinical practice guideline is trustworthy.

JAMA 309, 139–140.Sampson, M., McGowan, J., Cogo, E., Grimshaw, J., Moher, D. (2009).

An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review

of electronic search strategies.

J Clin Epidemiol 62, 944–952.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2013).

Management of Chronic Pain. A National Clinical Guideline

(Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).Shaneyfelt, T.M., Centor, R.M. (2009).

Reassessment of clinical practice guidelines: Go gently into that good night.

JAMA 301, 868–869.Shaneyfelt, T.M., Mayo-Smith, M.F., Rothwangl, J. (1999).

Are guidelines following guidelines? The methodological quality of

clinical practice guidelines in the peer-reviewed medical literature.

JAMA 281, 1900–1905.Shekelle, P.G., Woolf, S.H., Eccles, M., Grimshaw, J. (1999).

Clinical guidelines: Developing guidelines.

BMJ 318, 593–596.Shekelle, P, Woolf, S, Grimshaw, JM, Schunemann, HJ, and Eccles, MP.

Developing Clinical Practice Guidelines: Reviewing, Reporting, and

Publishing Guidelines; Updating Guidelines; and the Emerging

Issues of Enhancing Guideline Implementability and

Accounting for Comorbid Conditions in Guideline Development

Implementation Science 2012 (Jul 4); 7: 62Slade, S.C., Kent, P., Patel, S., Bucknall, T., Buchbinder, R. (2015).

Barriers to primary care clinician adherence to clinical guidelines

for the management of low back pain: a systematic review

and metasynthesis of qualitative studies.

Clin J Pain. 2015 Dec 24. [Epub ahead of print]Tricoci, P., Allen, J.M., Kramer, J.M., Califf, R.M., Smith, S.C. Jr (2009).

Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines.

JAMA 301, 831–841.van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, et al; On behalf of the COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for the Management of Acute Low Back Pain in Primary Care.

Chapter 3. European Guidelines for the Management of Acute

Nonspecific Low Back Pain in Primary Care

European Spine Journal 2006 (Mar); 15 Suppl 2: S169–191Walker, B.F. (2000).

The prevalence of low back pain: A systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998.

J Spinal Disord 13, 205–217.Whitworth, J.A. (2006).

Best practices in use of research evidence to inform health decisions.

Health Res Policy and Syst 4, 11.Williams, C.M., Maher, C.G., Latimer, J., McLachlan, A.J., Hancock, M.J., Day, R.O., Lin, C.W. (2014).

Efficacy of paracetamol for acute low-back pain:

A double-blind, randomised controlled trial.

Lancet 384, 1586–1596.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to LOW BACK GUIDELINES

Since 11–25–2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |