ISSLS Prize Winner:

Consensus on the Clinical Diagnosis of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis:

Results of an International Delphi Study.This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016 (Aug 1); 41 (15): 1239–1246 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Christy Tomkins-Lane, PhD, Markus Melloh, MD, PhD, Jon Lurie, MD, Matt Smuck, MD, Michele Battie, PhD, Brian Freeman, MD, Dino Samartzis, MD, PhD, Richard Hu, MD, Thomas Barz, MD, Kent Stuber, DC, Michael Schneider, DC, PhD, Andrew Haig, MD, Constantin Schizas, MD, Jason Pui Yin Cheung, MD, Anne F. Mannion, PhD, Lukas Staub, MD, PhD, Christine Comer, PhD, Luciana Macedo, PhD, Sang-ho Ahn, Kazuhisa Takahashi, MD, PhD, and Danielle Sandella, MS

Department of Health and Physical Education,

Mount Royal University,

Calgary, Canada

STUDY DESIGN: Delphi.

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to obtain an expert consensus on which history factors are most important in the clinical diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS).

SUMMARY OF BACKGROUND DATA: LSS is a poorly defined clinical syndrome. Criteria for defining LSS are needed and should be informed by the experience of expert clinicians.

METHODS: Phase 1 (Delphi Items): 20 members of the International Taskforce on the Diagnosis and Management of LSS confirmed a list of 14 history items. An online survey was developed that permits specialists to express the logical order in which they consider the items, and the level of certainty ascertained from the questions. Phase 2 (Delphi Study) Round 1: Survey distributed to members of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. Round 2: Meeting of 9 members of Taskforce where consensus was reached on a final list of 10 items. Round 3: Final survey was distributed internationally. Phase 3: Final Taskforce consensus meeting.

RESULTS: A total of 279 clinicians from 29 different countries, with a mean of 19 (±SD: 12) years in practice participated.

The six top items were"leg or buttock pain while walking,"

"flex forward to relieve symptoms,"

"feel relief when using a shopping cart or bicycle,"

"motor or sensory disturbance while walking,"

"normal and symmetric foot pulses,"

"lower extremity weakness," and

"low back pain."Significant change in certainty ceased after six questions at 80% (P < .05).

CONCLUSION: This is the first study to reach an international consensus on the clinical diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS), and suggests that within six questions clinicians are 80% certain of diagnosis. We propose a consensus-based set of "seven history items" that can act as a pragmatic criterion for defining LSS in both clinical and research settings, which in the long term may lead to more cost-effective treatment, improved health care utilization, and enhanced patient outcomes.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE: 2.

Keywords: lumbar spinal stenosis, diagnosis, Delphi study, history, consensus, neurogenic claudication

From the FULL TEXT Article:

INTRODUCTION

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a common degenerative condition of the spine, leading to significant pain, disability and functional limitations. [1–9] The prevalence of LSS is estimated to be 9% in the general population, and up to 47% in people over age 60. [10] LSS is the most common reason for spine surgery in patients over 65, [11] with a current estimated 2–year cost of $4 billion in the US. [12, 13] Given the aging population, both the prevalence and economic burden of LSS are expected to increase dramatically. [1, 11–16]

Lumbar spinal stenosis, first described by Verbiest in 1954, [18] has evolved from an anatomical concept to a poorly defined clinical syndrome. [19] LSS is currently recognized by the North American Spine Society as “a clinical syndrome of buttock or lower extremity pain, which may occur with or without back pain, associated with diminished space available for the neural and vascular elements in the lumbar spine.” [1] However, there is no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis of LSS. [20, 21] Currently, diagnosis is based on a complex integration of factors including history, physical examination, and imaging studies. [20, 22–24]

Clinical care and research in LSS is complicated by the heterogeneity of the condition, and the lack of standard criteria for diagnosis. [20–23, 25] This dearth of standardized criteria in studies of treatment outcomes has resulted in a lack of clarity regarding which management approaches are best. [26–28] Given these significant limitations in LSS care and research, along with increasing prevalence, [10, 13, 24] and increasing costs associated with treating LSS, [12–15, 29–33] it is imperative to establish a set of core diagnostic criteria. [20, 21, 34] With the rise of personalized medicine and the need for cost-effective and optimized health-care utilization, proper diagnostics have taken center-stage. Defining a core set of diagnostic criteria for LSS would refine outcomes assessment and lead to more cost-effective and targeted clinical care.

In the absence of valid objective criteria, it has been suggested that expert opinion be considered the ‘gold standard’ in the diagnosis of LSS. [6] The most valid approach to establishing a set of diagnostic criteria is to leverage the expertise of clinicians experienced in the diagnosis and treatment of LSS. This type of study is known as a Delphi approach, and has been applied successfully in defining diagnostic criteria for low back pain. [35, 36] While there have been a number of attempts to define diagnostic criteria for LSS, none have used such an international expert consensus approach.

Given the complexity of diagnosing LSS, it is logical to approach a diagnostic consensus in stages, starting with historical findings. Many studies have demonstrated the importance and practicality of the patient history in the diagnosis of LSS. [9, 20, 22, 37–40] However, no studies to date have employed a Delphi consensus approach to determine which factors are most important. The purpose of this study was to reach a consensus among international experts on which factors obtained from the history are most important in the diagnosis of clinical LSS. To do this we leveraged innovative online survey methodology to reach a large multi-disciplinary, and international group of LSS experts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Figure 1

Table 1 At the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine (ISSLS) annual meeting in Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2012, the Taskforce on Diagnosis and Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis was formed, with the express aim to work on gaps in the evidence for LSS. This Taskforce is comprised of researchers and clinical spine specialists including neurosurgeons, orthopaedic surgeons, physiatrists, physical therapists, and chiropractors from North and South America, Europe, Asia, and Australia. At this meeting, the Delphi study was initiated to generate a consensus among international experts on which historical items are considered the most important in the clinical diagnosis of LSS. This study received a human research ethics waiver through Stanford University. An outline of the Delphi process can be seen in Figure 1.

Phase 1: Delphi ItemsPhase 1, Round 1: Initial Delphi Items A multidisciplinary team of experts compiled a list of 14 clinical questions considered to be important in the diagnosis of LSS. The group included a spine neurosurgeon, a vascular surgeon, an electromyography expert, physiatrists, and a radiographer. [41] Following the compilation of the list of items, an online survey was developed to determine which items were most important to clinicians when diagnosing LSS.

Online Survey The online survey was developed using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics Labs, Inc. Provo, UT). This innovative survey was designed to allow specialists to express the logical order in which they consider the questions, and the level of certainty ascertained from the questions, when diagnosing LSS. [41] In the survey, responders were provided with the following information: “A patient over 65 years old comes into your office with symptoms they attribute to the low back or leg.” Responders were then asked, “You are interested in finding out if they have the clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis. What is the first question you would ask?” The responder then chose one of the 14 items in the list. Following item selection, the responder was then informed of the patient’s affirmative answer, and then asked to rate, based on all known information, how certain they were that the patient had LSS. [41] Certainty was rated on a sliding visual analog scale, anchored by 0, “not at all certain” and 100, “completely certain.” [41] This process was repeated up to a maximum of ten times, or until the responder decided to stop the survey. The 14 items included in this survey can be found in Table 1. Two of the items (frequent headaches and thyroid dysfunction) are irrelevant to LSS, to ensure true participation vs. random-choice. This survey was distributed to Physiatrists through email, as well as posting on the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Forum.

Phase 1, Round 2: Delphi Items Taskforce Consensus Results of Phase 1, Round 1 were limited to Physiatrists practicing in the United States of American (USA). It was therefore unreasonable to generalize findings to other geographic locations. Also, results of Round 1 were not representative of different specialties practicing in spine care. Therefore, following completion of Round 1, we proceeded to Phase 1, Round 2 (Delphi Items Taskforce Consensus). At the 2013 ISSLS Annual Meeting in Scottsdale, USA a consensus meeting of the members of the Taskforce was held, supported by ISSLS as an official Focus Group. The group discussed the 14 items included in the Round 1 online survey to decide whether the items were appropriate for distribution in Phase 2, Delphi Study.

Phase 2: Delphi StudyPhase 2, Round 1: Survey of International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine Members The online survey described above was distributed by email to all ISSLS members.

Phase 2, Round 2: Taskforce Item Consensus Following completion of Phase 2, Round 1, an in-person meeting of members of the Taskforce was conducted as a Focus Group Meeting at ISSLS 2014, in Seoul, Korea. The objective of this meeting was to review the results of the Phase 2, Round 1 survey to determine whether any changes to the survey items or structure were required prior to Round 3.

Phase 2, Round 3: International Survey Following revisions to the survey that were guided by Taskforce discussions in Round 2, the final version was distributed to a wide group of experts, with the goal of obtaining 200 responses. The survey was distributed through the following societies: ISSLS, International Spine Intervention Society, British Association of Spine Surgeons, British Scoliosis Society, Canadian Spine Society, Asia Pacific Orthopaedic Association, and the Hong Kong Orthopaedic Association.

Phase 3: Taskforce Final Consensus

Following compilation of results from Round 3, the Taskforce met as a Focus Group at ISSLS 2015 in San Francisco, USA. At this meeting, the results of the international survey were discussed and the final list of historical items was confirmed.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the number of times each question was asked, and in which order. The impact of the number of questions asked on physician certainty was determined by calculating the change in certainty after each question was asked, regardless of question order. A paired-samples t-test was used to determine significant changes in certainty with each question asked. The physicians’ certainty of diagnosis based on the total number of questions asked was determined to establish whether a maximal level of certainty is achieved after a particular number of questions. [41] Significance level was set at p<.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS Version 22 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Phase 1, Round 1: Initial Delphi Items

Respondents from Round 1 included 97 Physiatrists practicing in the USA with a mean of 10 years in practice. Fifty-seven percent (%) of the participants worked in private practice, while 29% worked in a hospital. [41] Leg pain while walking, the need to sit down or bend forward to relieve pain, and flexing forward while walking were the most commonly asked questions. Statistically significant change in certainty ceased after 6 questions at 86.2% certainty (p<0.05). [41]

Phase 1, Round 2: Taskforce Items Consensus

Following review of the items in the Round 1 survey, the 20 members of the Taskforce were unanimous in confirming that the original 14 items were appropriate for inclusion in the Phase 2 survey.

Phase 2, Round 1: Survey of International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine Members

The online survey was distributed to all ISSLS members by email. Sixty-eight individuals from 16 different countries participated. Of the 14 items, the most commonly selected factors were “leg pain while walking”, “flex forward while walking to relieve symptoms”, “sit down or bend forward to relieve pain”, “normal foot pulses”, “relief with rest”, and “lower extremity weakness”. Significant change in certainty ceased after 6 questions at 81% certainty (p<0.05).

Phase 2, Round 2: Taskforce Items Consensus

Following completion of Phase 2, Round 1, a consensus discussion of 9 members of the Taskforce was held as a Focus Group meeting at ISSLS 2014 in Seoul, Korea. Based on consensus, a number of changes were made to the online survey. The changes were intended to focus and streamline the question set. It was decided to cut the number of questions to 10, and have just one question being irrelevant to LSS. Questions were presented in random order to ensure that there would be no impact of presentation order on question selection. After these amendments the new survey was distributed to all Taskforce members for further input, and then, final approval by all members. The final questions are listed in Table 1.

Phase 2, Round 3: International Survey

Table 2

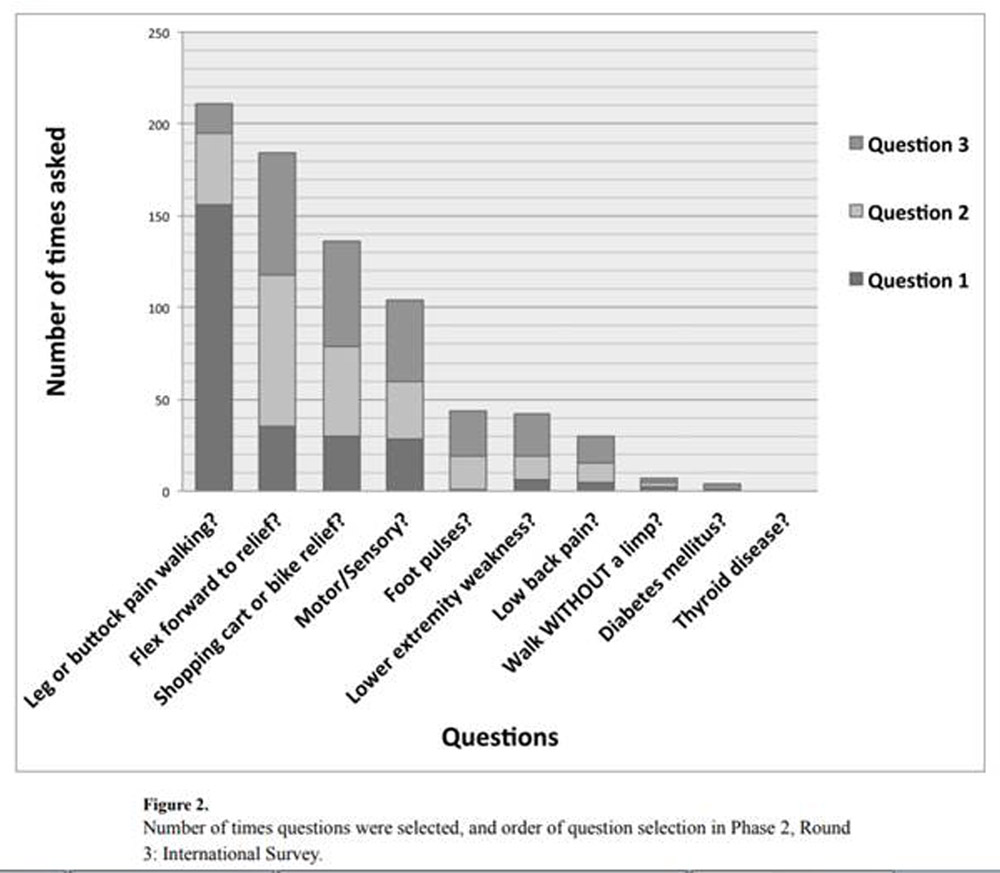

Figure 2

Table 3

The final survey was completed by 279 individuals from 29 different countries (Table 2). All participants identified as professionals practicing in diagnosis and care of LSS. There was good representation by specialty and type of practice. The mean number of years in practice was 19 (±SD: 12).

The order of questions asked by respondents is shown in Figure 2, and details regarding the first three items selected in Table 3. By far, the question asked most often was ‘does the patient have leg or buttock pain while walking?’ This question was asked by 78% of respondents, and was the first question asked by 59%. The second most popular question ‘does the patient flex forward to relieve symptoms?’ was asked by 58% of respondents. No respondents selected the thyroid disease question, suggesting that all responses were actual choices and not random selections. Statistically significant change in certainty ceased after 6 questions at 80.0% certainty (p<0.05).

Throughout the questionnaire, participants were permitted to add their own items if they felt that the options did not adequately capture their questions. The Taskforce reviewed these additional questions and determined that the constructs addressed were all adequately represented in the existing question set.

Phase 3: Taskforce Final Consensus

At the 2015 ISSLS meeting in San Francisco, USA, 11 members of the Taskforce met for the final consensus. The set of 6 top items was confirmed, along with the addition of the 7th most popular item: “Does the patient have low back pain”. It was the consensus of the Taskforce that the presence of low back pain is an important component of history taking for LSS diagnosis, and should be included.

The top items are numbers 1–7 in Table 3.

Discussion

This ground-breaking study is the first to reach an international consensus on which history factors are most important in the clinical diagnosis of LSS. While other studies have examined diagnosis of LSS, none have sourced such a large multi-disciplinary group of experts in varying specialties and geographic locations. Using innovative online surveys, this study evaluated which factors are most important in the diagnosis, how many questions are needed in order to gain reasonable certainty, and how certain clinicians can be after asking their questions. [41] Results suggest that within 6 historical questions clinicians become 80% certain about the diagnosis of LSS. We propose a consensus-based set of “7 history items” that can act as a practical criterion for defining LSS in both clinical and research settings.

Results of this study corroborate previous investigations. [4, 8, 10, 22, 37, 42–46] The item selected most frequently was ‘Does the patient have leg or buttock pain while walking?’ This is not surprising given that this item represents neurogenic claudication, recognized to be the hallmark of LSS. [2, 26, 27, 47, 48]

A recent systematic review found that the most useful historical findings in diagnosing LSS include age, radiating leg pain exacerbated while standing/walking, absence of pain when seated, improvement of symptoms when bending forward, and wide-based gait. [20] Another recent systematic review focusing on clinical prediction rules also found that older age, pain with standing/walking, and relief with sitting/bending were common independent predictors across all LSS prediction rules. [38–40, 49]

However, none of the previously cited studies employed an international consensus approach, and only one of these prediction rules has been validated. [38, 49] This validated prediction rule has a positive likelihood ratio of just 1.6 (95% CI: 1.3 –2.0), suggesting that it may have limited application in increasing diagnostic likelihood. [21]

Items identified as important in the present study, that were shown to be less sensitive or specific in the systematic reviews include the presence of motor or sensory disturbances while walking, lower extremity weakness, and low back pain. [37, 50] Validation studies are required to determine whether the inclusion of these items remains clinically useful.

There are a number of practical considerations when applying this set of items. The presence and symmetry of foot pulses is truly a physical examination item. It is likely more appropriate to examine foot pulses, rather than ask about them. It may also be practical to combine the items that are related to relief of symptoms with flexion (Do you flex forward to relieve symptoms? Do you feel relief when using a shopping cart or bicycle?). Simply asking whether the patient feels relief when bending forward should capture the desired information.

Strengths of this study include the ability to leverage the multifaceted expertise of international spine researchers and clinicians. This study demonstrates the value of multi-disciplinary research societies that bring together experts from around the world to discuss important issues. Specifically, this Taskforce was originated based on discussions among experts at ISSLS meetings about the importance of LSS diagnosis, research, and clinical care, and was supported by ISSLS as a Focus Group. The use of innovative online survey methodology was another strength of the study. This allowed the investigators to reach a broad spectrum of specialists across 29 different countries allowing for anonymous and unbiased responses.

While this set of historical items provides a practical tool for diagnosis of LSS, there are limitations. Results of this study are geographically limited to members of the societies who were willing to distribute the survey. Additionally, this study included only historical items, and does not account for other diagnostic tests. In order to meet this goal, the Taskforce has initiated a second Delphi study to determine which other diagnostic factors increase the certainty of diagnosis, including physical examination findings, imaging, and electromyography. This study aims to recruit a larger number of participants with more broad geographical representation. The Taskforce is also working on studies to validate the findings of this Delphi study in clinical settings. Finally, while this set of items may be useful in understanding the clinical diagnosis of LSS, it by no means represents a conclusive criterion standard that can inform all aspects of diagnosis and care. It needs to be recognized that although diagnostic criteria can be useful, optimal care requires ongoing interaction between the clinician, assessment of the risks and benefits of treatments, and the needs and goals of the patient. [41]

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has reached an international consensus on the clinical diagnosis of LSS. Results suggest that within 6 questions, clinicians are 80% certain of the diagnosis. We propose a consensus-based set of “7 history items” that can act as a pragmatic criterion for defining clinical LSS in both clinical and research settings. This set of items can be used by researchers as a standardized criterion for inclusion in research studies, and by health-care providers both in teaching and clinical practice to provide more personalized and targeted care. In the long-term, use of this consensus-based criteria could lead to more cost-effective care, improved health-care utilization, and enhanced patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 3

Acknowledgments

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s). No funds were received in support of this work.

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: board membership, consultancy, expert testimony, stocks, grants, payment for lectures.

This paper is the result of the work by the following group:

The International Taskforce on the Diagnosis and Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis; The International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine (ISSLS) Focus Group on Diagnosis and Management of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

The authors wish to acknowledge the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine (ISSLS) for supporting our Taskforce as an ISSLS Focus Group. We would also like to acknowledge the following research societies for distributing our survey: ISSLS, International Spine Intervention Society, British Association of Spine Surgeons, British Scoliosis Society, Canadian Spine Society, Asia Pacific Orthopaedic Association, and the Hong Kong Orthopaedic Association.

References:

Deyo RA.

Treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis: a balancing act.

Spine J. 2010;10:625–627Ammendolia C, et al.

Nonoperative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis with neurogenic claudication:

a systematic review.

Spine. 2012;37:E609–E616Ammendolia C, et al.

What interventions improve walking ability in neurogenic claudication with lumbar

spinal stenosis? A systematic review.

Eur. Spine J. 2014;23:1282–1301Amundsen T, et al.

Lumbar spinal stenosis. Clinical and radiologic features.

Spine. 1995;20:1178–1186Arbit E, Pannullo S.

Lumbar stenosis: a clinical review.

Clin. Orthop. 2001:137–143Benoist M.

The natural history of lumbar degenerative spinal stenosis.

Jt. Bone Spine Rev. Rhum. 2002;69:450–457Binder DK, Schmidt MH, Weinstein PR.

Lumbar spinal stenosis.

Semin. Neurol. 2002;22:157–166Chad DA.

Lumbar spinal stenosis.

Neurol. Clin. 2007;25:407–418Conway J, Tomkins CC, Haig AJ.

Walking assessment in people with lumbar spinal stenosis: capacity, performance,

and self-report measures.

Spine J. 2011;11:816–823Kalichman L, et al.

Spinal stenosis prevalence and association with symptoms: the Framingham Study.

Spine J. 2009;9:545–550Deyo RA, Gray DT, Kreuter W, Mirza S, Martin BI.

United States trends in lumbar fusion surgery for degenerative conditions.

Spine. 2005;30:1441–1445. discussion 1446-1447Parker SL, et al.

Two-year comprehensive medical management of degenerative lumbar spine disease

(lumbar spondylolisthesis, stenosis, or disc herniation): a value analysis of cost, pain,

disability, and quality of life: clinical article.

J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2014;21:143–149Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI, Kreuter W, Goodman DC, Jarvik JG.

Trends, Major Medical Complications, and Charges Associated

with Surgery for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis in Older Adults

JAMA 2010 (Apr 7); 303 (13): 1259–1265Harrop JS, Hilibrand A, Mihalovich KE, Dettori JR, Chapman J.

Cost-effectiveness of surgical treatment for degenerative spondylolisthesis and

spinal stenosis.

Spine. 2014;39:S75–S85Ciol MA, Deyo RA, Howell E, Kreif S.

An assessment of surgery for spinal stenosis: time trends, geographic variations,

complications, and reoperations.

J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1996;44:285–290Lurie JD, Birkmeyer NJ, Weinstein JN.

Rates of advanced spinal imaging and spine surgery.

Spine. 2003;28:616–620Deyo RA.

Treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis: a balancing act.

Spine J. 2010;10:625–627Verbiest H.

A radicular syndrome from developmental narrowing of the lumbar vertebral canal.

J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1954;36-B:230–237Haig AJ, et al.

Spinal stenosis, back pain, or no symptoms at all? A masked study comparing radiologic

and electrodiagnostic diagnoses to the clinical impression.

Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006;87:897–903de Schepper EIT, et al.

Diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis: an updated systematic review of the accuracy

of diagnostic tests.

Spine. 2013;38:E469–E481Haskins R, Osmotherly PG, Rivett DA.

Diagnostic clinical prediction rules for specific subtypes of low back pain:

a systematic review.

J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015;45:61–76Katz JN, Dalgas M, Stucki G, Lipson SJ.

Diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis. Rheum.

Dis. Clin. North Am. 1994;20:471–483Genevay S, Atlas SJ.

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis.

Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2010;24:253–265Watters WC, et al.

Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: an evidence-based clinical guideline for

the diagnosis and treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis.

Spine J. 2008;8:305–310Haig AJ, Tomkins CC.

Diagnosis and management of lumbar spinal stenosis.

JAMA. 2010;303:71–72Ammendolia C, et al.

Nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis with neurogenic claudication.

Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;8:CD010712Atlas SJ, Delitto A.

Spinal stenosis: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment.

Clin. Orthop. 2006;443:198–207Zaina F, Tomkins-Lane C, Carragee E, Negrini S.

In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

The Cochrane Collaboration, editor.

John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. at

http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD010264Yelin E.

Cost of musculoskeletal diseases: impact of work disability and functional decline.

J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 2003;68:8–11Burnett MG, Stein SC, Bartels RHMA.

Cost-effectiveness of current treatment strategies for lumbar spinal stenosis:

nonsurgical care, laminectomy, and X-STOP.

J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2010;13:39–46Ong KL, Auerbach JD, Lau E, Schmier J, Ochoa JA.

Perioperative outcomes, complications, and costs associated with lumbar spinal fusion

in older patients with spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis.

Neurosurg. Focus. 2014;36:E5Tosteson ANA, et al.

Surgical treatment of spinal stenosis with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis:

cost-effectiveness after 2 years.

Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;149:845–853Deyo RA, Mirza SK.

Trends and variations in the use of spine surgery.

Clin. Orthop. 2006;443:139–146Haig AJ, et al.

Reliability of the clinical examination in the diagnosis of neurogenic versus

vascular claudication.

Spine J. 2013;13:1826–1834Chan AYP, Ford JJ, McMeeken JM, Wilde VE.

Preliminary evidence for the features of non-reducible discogenic low back pain:

survey of an international physiotherapy expert panel with the Delphi technique.

Physiotherapy. 2013;99:212–220Konstantinou K, Hider SL, Vogel S, Beardmore R, Somerville S.

Development of an assessment schedule for patients with low back-associated leg pain

in primary care: a Delphi consensus study.

Eur. Spine J. 2012;21:1241–1249Iversen MD, Katz JN.

Examination findings and self-reported walking capacity in patients with

lumbar spinal stenosis.

Phys. Ther. 2001;81:1296–1306Kato Y, et al.

Validation study of a clinical diagnosis support tool for lumbar spinal stenosis.

J. Orthop. Sci. 2009;14:711–718Cook C, et al.

The clinical value of a cluster of patient history and observational findings

as a diagnostic support tool for lumbar spine stenosis.

Physiother. Res. Int. J. Res. Clin. Phys. Ther. 2011;16:170–178Sugioka T, Hayashino Y, Konno S, Kikuchi S, Fukuhara S.

Predictive value of self-reported patient information for the identification

of lumbar spinal stenosis.

Fam. Pract. 2008;25:237–244Sandella DE, Haig AJ, Tomkins-Lane C, Yamakawa KSJ.

Defining the clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis:

a recursive specialist survey process.

PM R. 2013;5:491–495. quiz 495Katz JN, et al.

Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Diagnostic value of the history and

physical examination.

Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1236–1241Binder DK, Schmidt MH, Weinstein PR.

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis.

Semin. Neurol. 2002;22:157–166Lin S-I, Lin R-M.

Disability and walking capacity in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis:

association with sensorimotor function, balance, and functional performance.

J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2005;35:220–226Ciricillo SF, Weinstein PR.

Lumbar spinal stenosis.

West. J. Med. 1993;158:171–177Tomkins-Lane CC, Battié MC.

Predictors of objectively measured walking capacity in people with degenerative

lumbar spinal stenosis.

J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2013;26:345–352Deen HG, et al.

Measurement of exercise tolerance on the treadmill in patients with symptomatic

lumbar spinal stenosis: a useful indicator of functional status and surgical outcome.

J. Neurosurg. 1995;83:27–30Porter RW.

Spinal stenosis and neurogenic claudication.

Spine. 1996;21:2046–2052Konno S, et al.

Development of a clinical diagnosis support tool to identify patients with lumbar spinal stenosis.

Eur. Spine J. 2007;16:1951–1957Johnsson KE, Rosén I, Udén A.

Neurophysiologic investigation of patients with spinal stenosis.

Spine. 1987;12:483–487

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to LOW BACK GUIDELINES

Since 4-29-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |