Deconstructing Chronic Low Back Pain in the Older Adult -

Step by Step Evidence and Expert-Based Recommendations

for Evaluation and Treatment.

Part I: Hip OsteoarthritisThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Pain Medicine 2015 (May); 16 (5): 886897 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Debra K. Weiner, Meika Fang, Angela Gentili, Dr. Gary Kochersberger,

Zachary A. Marcum, Michelle I. Rossi, Todd P. Semla, Joseph Shega

Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center,

VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System,

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.OBJECTIVE: To present the first in a series of articles designed to deconstruct chronic low back pain (CLBP) in older adults. The series presents CLBP as a syndrome, a final common pathway for the expression of multiple contributors rather than a disease localized exclusively to the lumbosacral spine. Each article addresses one of twelve important contributors to pain and disability in older adults with CLBP. This article focuses on hip osteoarthritis (OA).

METHODS: The evaluation and treatment algorithm, a table articulating the rationale for the individual algorithm components, and stepped-care drug recommendations were developed using a modified Delphi approach. The Principal Investigator, a five-member content expert panel and a nine-member primary care panel were involved in the iterative development of these materials. The algorithm was developed keeping in mind medications and other resources available within Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities. As panelists were not exclusive to the VHA, the materials can be applied in both VHA and civilian settings. The illustrative clinical case was taken from one of the contributor's clinical practice.

RESULTS: We present an algorithm and supportive materials to help guide the care of older adults with hip OA, an important contributor to CLBP. The case illustrates an example of complex hip-spine syndrome, in which hip OA was an important contributor to disability in an older adult with CLBP.

CONCLUSIONS: Hip OA is common and should be evaluated routinely in the older adult with CLBP so that appropriately targeted treatment can be designed.

KEYWORDS: Aged; Assessment; Chronic Low Back Pain; Chronic Pain; Elderly; Hip Osteoarthritis; Low Back Pain; Primary Care

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

An estimated one in two people with hip osteoarthritis (OA) has low back pain (LBP). [1] The Hip-Spine Syndrome (HSS) was first described by Offierski in 1983. [2] Three types of patients were described those with simple HSS who had pathology of both the hip and lumbar spine, but disability related to only one source; those with complex HSS who had symptoms from both the hip and spine without a clear single source of disability, such as patients with low back and leg pain and who have clinical evidence of both lumbar spinal stenosis and hip OA [3]; and those with secondary HSS who have inter-related pathology such as restricted hip motion from advanced OA causing abnormal biomechanics of the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex and consequent LBP. [4] Secondary HSS has been substantiated through studies demonstrating significant reduction or complete resolution of LBP in patients with hip OA following total hip arthroplasty (THA). [57]

Spinal pathology does not always lead to spinal pain. Much of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-identified degenerative lumbar pathology is incidental in older adults and its identification may lead to invasive procedures that are ineffective and sometimes dangerous. A study of individuals age 65 and older that included 162 participants with chronic low back pain (CLBP) and 158 pain-free revealed x-ray evidence of degenerative disc disease in 95%, both those with CLBP and those pain-free. [8] Jarvik et al. studied 148 pain-free individuals with lumbar MRI, and 21% of those > age 65 (six of 29 individuals) had evidence of moderate or severe stenosis of the central canal, as compared with 11% of those age 5565 and 67% of those9] As noted in the series overview in this issue of Pain Medicine, CLBP associated with functional compromise in the older adult should be approached as a geriatric syndrome, that is, as a final common pathway fed by multiple contributors. [10] These patients should routinely be evaluated for contributors to pain and disability that lie outside of the spinal skeleton such as hip OA, as this and other extraspinal factors may directly cause part or all of the patient's LBP or they may independently contribute to disability.

Preliminary data indicate that as many as one in four older adults with CLBP may have physical examination evidence of hip OA that is typically one of multiple contributors to their pain and disability. [11] Patients with hip OA may experience pain in their groin, buttocks, thigh, and/or distal lower extremity [12], and this could be misconstrued as pain emanating from pathology of the lumbar spine (e.g., radiculopathy). Identifying the hip rather than the back as a key pain generator could substantively impact management. We present a patient who has CLBP with hip OA being at least one contributor to his pain and difficulty functioning. This case demonstrates the clinical complexity of older patients with chronic low back and/or leg pain, comorbid hip and spine pathology, and a pragmatic approach to management of their musculoskeletal pain.

Methods

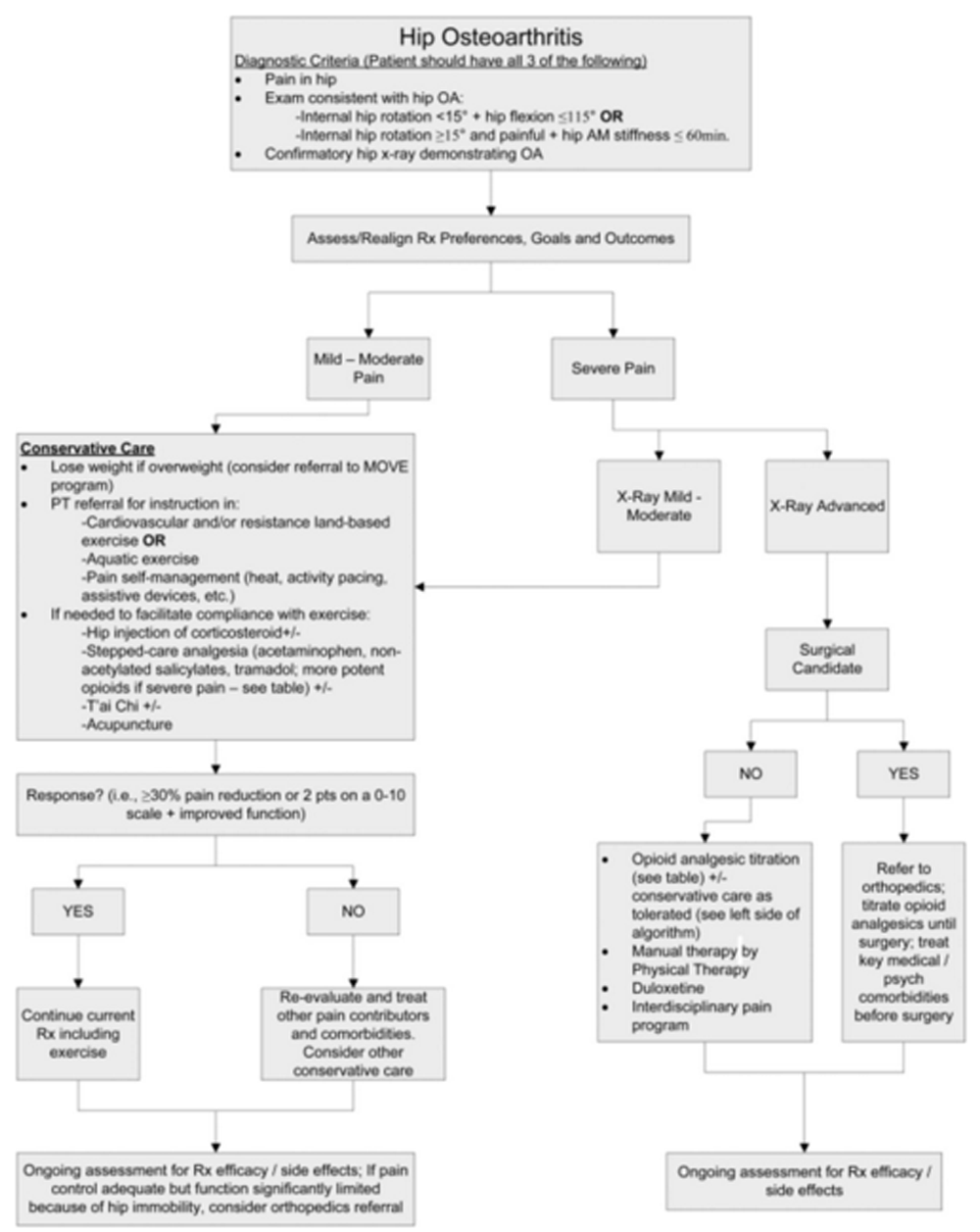

A modified Delphi technique involving a content expert panel and a primary care review panel, as per the detailed description provided in the series overview [13], was used to create the algorithm (Figure 1), the table providing the rationale for the various components of the algorithm (Table 1), and the stepped-care medication table (Table 2).

Expertise represented among the 5 Delphi expert panel members for the hip OA algorithm included geriatric medicine, geriatric pharmacology and rheumatology.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the evaluation and treatment of hip OA in an older adult.

Table 1.

Maladaptive coping: theoretical and pragmatic underpinnings of algorithm recommendations

Algorithm component Comments Hip OA diagnostic criteria We have not included ESR < 20 mm/hr as a criterion given the nonspecificity of modestly elevated ESR in older adults. We also have not included age >50 as this applies to all older adults. 30% pain reduction as significant Data on 2724 subjects from 10 placebo controlled trials of pregabalin in diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, CLBP, fibromyalgia, and OA. Cardiovascular and/or resistance land-based exercise ACR strongly recommends Aquatic exercise ACR strongly recommends.

This should be recommended for people who prefer it to land-based exercise (LBE) or who are unable to tolerate LBE.Pain Self-Management Program ACR recommends conditionally.

High quality evidence is lacking specifically in older adults. Arthritis pain self-management programs that contain some CBT elements demonstrate efficacy.

Programs appear to benefit self-efficacy but not pain or physical functioning.Weight loss Prescribe for those who are overweight;

ACR strongly recommends.Acetaminophen The 30003250 mg/day maximum is an FDA suggestion (not a mandate) and is based on no data in adults. Nonacetylated salicylates ACR conditionally recommends oral NSAIDs.

Traditional NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) should not be used chronically in older adults because of the potential for multiple adverse effects including but not limited to gastrointestinal bleeding, renal insufficiency, and exacerbation of hypertension and congestive heart failure.

As celecoxib also has many of these deleterious effects, it is not recommended for long-term use in older adults. NOTE: The 2012 Beers Criteria do not include celecoxib as a contraindicated drug; the AGS 2009 Pain Guidelines recommend against its chronic use in older adults.Tramadol This agent is recommended prior to considering other opioids based on the combined evidence from two Cochrane reviews. Overall benefits from any opioid or opioid-like drug are modest. It is not clear that benefits outweigh risks. Duloxetine Duloxetine is FDA-approved for the treatment of OA pain.

There is evidence of efficacy in older adults with knee OA pain, but not specifically for hip OA.T'ai Chi If available, T'ai Chi is recommended as the first CAM modality that should be tried because of strong evidence supporting its efficacy in preventing falls in older adults (an important comorbidity in older adults with chronic pain) and its modest efficacy evidence for reducing pain and improving function in older adults with hip OA. Acupuncture As with most CAM interventions, further research is needed before any can be recommended strongly. Acetaminophen with codeine not recommended Codeine's adverse effect profile argues against using it in older adults.

Table 2.

Stepped care drug management of hip OA pain

Drug Dose/Titration

(Note: Abbreviations such as bid should be avoided in an effort to reduce errors.)Important Adverse Effects/Precautions First Line Treatment Intra-articular corticosteroid n/a Diabetics must monitor glucose carefully following procedure. Acetaminophen 3251000 mg q46h while awake, max 30003250 mg/day

Adjust dosing interval for renal function: CRcl 1050: q6 hours; CRcl < 10: q8 hoursAsk about all OTCs with acetaminophen; increased toxicity from chronic use if heavy EtOH use, malnourishment, preexisting liver diseasedecrease maximum daily dose to 2 g. The manufacturer's label lists a maximum daily dose of 3000 mg for extra strength (500 mg) tablets or capsules, and 3250 mg for regular strength (325 mg) tablets and capsules. Health care professionals may still prescribe or recommend a maximum of 4000 mg per day. Second Line Treatment Salsalate Choline magnesium trisalicylate 500750 mg twice daily; maximum dose 3000 mg/day 750 mg three times daily; max 3 g/day Does not interfere with platelet function; GI bleeding & nephrotoxicity rare; salicylate concentrations can be monitored if toxicity suspected. As these drugs are salicylates, providers should educate patients about symptoms associated with salicylism (e.g., nausea, vomiting, tinnitus, vertigo, reversible hearing loss, etc.). Avoid in patients with advanced renal disease or hepatic impairment Third Line Treatment Tramadol Start 25 mg once a day; increase by 2550 mg daily in divided doses every 37 days as tolerated to max dose of 100 mg four times a day. Renal dosing (CRcl <30 mL/minutes) 50100 mg twice a day. Max. 200 mg/day. Seizures and orthostatic hypotension. Other side effects similar to traditional opioids including constipation, sedation, confusion, respiratory depression. Potential for serotonin syndrome if patient is on other serotonergics. Do not use extended-release product if CRCl <30 mL/min.

Hydrocodone/acetaminophen

2.5/325 or 5/32510/325 mg q46h. Consider recommending a supplementary dose of APAP 325 with combination dose for additional analgesia before increasing the opioid dose. Total acetaminophen dose not to exceed 30003250 mg/day.For all opioids, increased risk of falls in patients with dysmobility. May worsen or precipitate urinary retention when BPH present. Increased risk of delirium in those with dementia.

Because of increased sensitivity to opioids older adults at greater risk for sedation, nausea, vomiting, constipation, urinary retention, respiratory depression, and cognitive impairment.

Start stimulant laxative (e.g., senna) to prevent/treat constipation. Many would start at opioid initiation if patient has existing complaints of constipation or other risk factors. Some providers advocate ensuring that all patients in whom opioids are initiated have a stimulant laxative readily available and start it at the first sign of constipation.

Exercise caution and follow closely if opioids are started in patients who drive. Avoid concomitant prescription of opioids and other CNS depressants.

Risk of addiction/diversion present with all opioids. Before starting an opioid, assess risk with the Opioid Risk Tool and during maintenance, monitor using tool such as Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM).

Tools available at www.painedu.org.

Oxycodone or morphineStart with 2.5 mg oxycodone or morphine q4h and titrate no more frequently than q 7 days; assess total needs after 7 days on stable dose, then convert to long acting.

Morphine

Dosing in Renal Impairment:

Clcr 1050 mL/minute: Administer at 75% of normal dose; Clcr <10 mL/minute: Administer at 50% of normal dose.

Dosing in Hepatic Impairment:

No dosage adjustment provided in manufacturer's labeling. Pharmacokinetics unchanged in mild liver disease; substantial extrahepatic metabolism may occur. In cirrhosis, increases in half-life and AUC suggest dosage adjustment required.

Oxycodone

Dosing in Renal Impairment:

Serum concentrations are increased ~50% in patients with Clcr <60 mL/minute; adjust dose based on clinical situation.

Dosing in Hepatic Impairment:

Immediate release: Reduced initial doses may be necessary (use a conservative approach to initial dosing); adjust dose based on clinical situation.

Controlled release: Decrease initial dose to one-third to one-half the usual starting dose; titrate carefully.Side effects and risks of addiction/diversion as per hydrocodone.

NEVER start long acting opioid before determining needs with short acting.Other Considerations Duloxetine Start 2030 mg/day; increase to 60 mg/day in 7 days. Not recommended in ESRD or CLcr<30. May precipitate serotonin syndrome when combined with triptans, tramadol, and other antidepressants. Key drug-disease interactions: HTN, uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma, seizure disorder. Precipitation of mania in patients with bipolar disorder. Important adverse effects include nausea, dry mouth, sedation/falls, urinary retention, and constipation. Contraindicated with hepatic disease and heavy alcohol use. Abrupt discontinuation may result in withdrawal syndrome. Contraindicated within 14 days of MAOI use.

Case Presentation

Relevant History

The patient is an 85year-old man who presented to the Pain Clinic in 2012 with a 50year history of LBP that started with an injury in 1960. He was treated with a discectomy in 1961, repeat back surgery in 1963, and a L4L5 laminectomy and fusion in 2008. He reports a several year history of increasing achy right-sided LBP with radiation into his buttocks and upper outer thigh. His pain severity ranges from 37/10 with an average of 5/10. Prolonged standing and/or walking exacerbates his pain and sitting alleviates it. He can stand 25 minutes and/or walk ~100 feet before he has to sit down because of pain. He denies lower extremity weakness, change in his bowel or bladder habits, fever, trauma, weight loss, or recent cancer associated with the worsening of his pain. He has tried hydrocodone, amitriptyline, several different nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and physical therapy (PT), all without significant reduction in pain or improvement in function. The only thing other than sitting or lying down that reduces his pain is oxycodone 5 mg/acetaminophen 325 mg, one pill three times daily. This regimen results in pain reduction from an average of 85 (on a 010 scale) for about 3 hours.

Relevant Physical Examination

The patient is awake, alert, oriented ×3, cooperative and in no apparent distress. Gait: Antalgic, favoring the right leg. Lumbar Spine: There is no tenderness over the spinous processes. The patient reports pain with forward flexion localized to the left paralumbar and sacroiliac joint regions and pain with extension that he experiences bilaterally. Hips: Internal rotation of the right hip is 10° and painful. Internal rotation of the left hip is not painful and 30±.

Imaging

An AP pelvis x-ray (Figure 2) revealed severe joint space narrowing and subchondral sclerosis of the right hip (arrow in Figure 2) and mild joint space narrowing of the left hip.

Figure 2.

AP pelvis X-ray demonstrating severe joint space narrowing and subchondral sclerosis

of the right hip (arrow) and mild joint space narrowing of the left hip

Clinical Course

The patient's oxycodone/acetaminophen was titrated to 2 pills four times daily and he experienced better pain relief and continued to be active. He was not interested in THA. Because of increasing pain and difficulty climbing stairs, 9 months later he underwent a fluoroscopically guided intra-articular hip injection with complete alleviation of his buttocks and leg pain and modest reduction of his LBP. He reported significant reduction of pain interference with his daily activities and sought consultation regarding THA.

Approach to Management

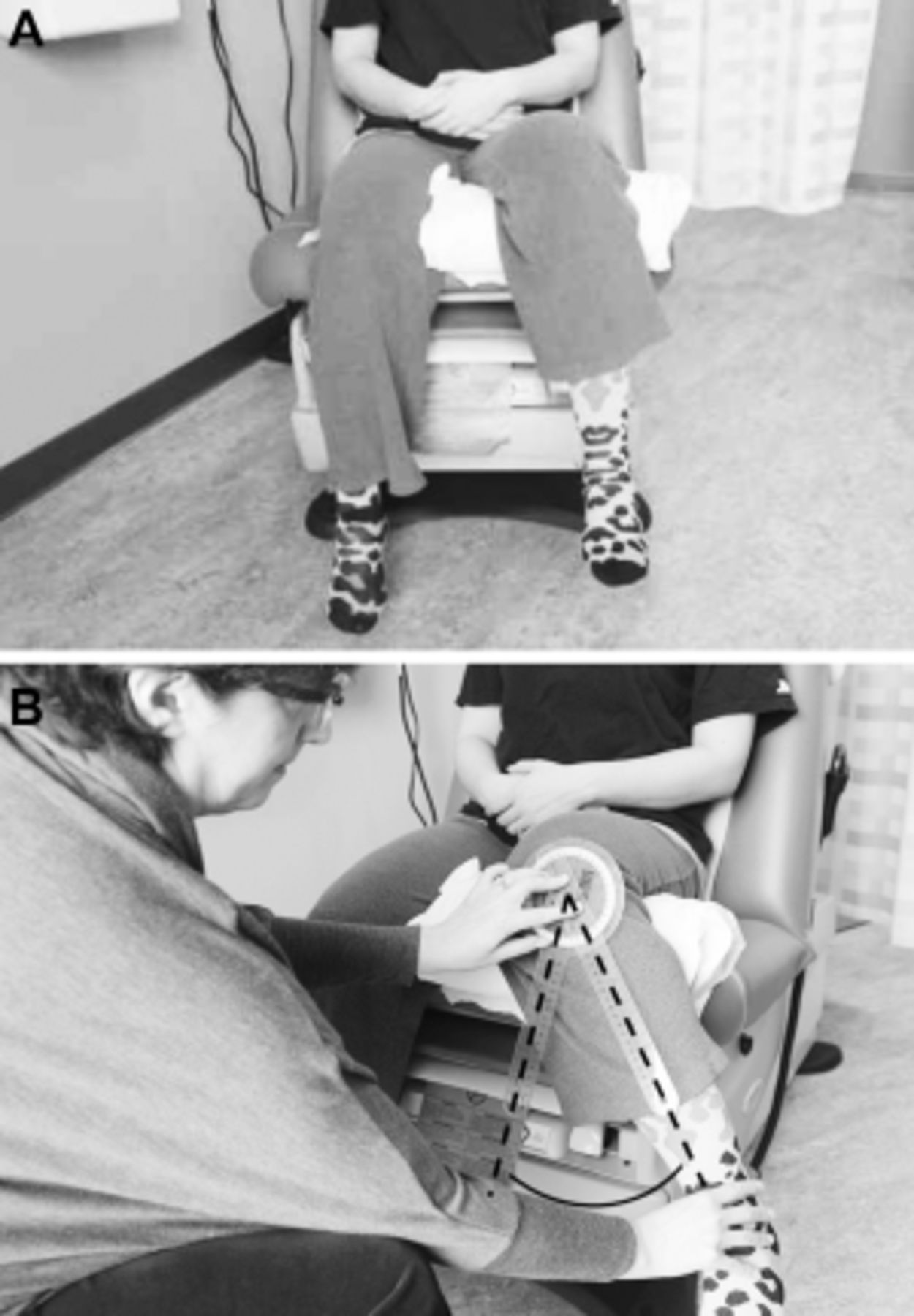

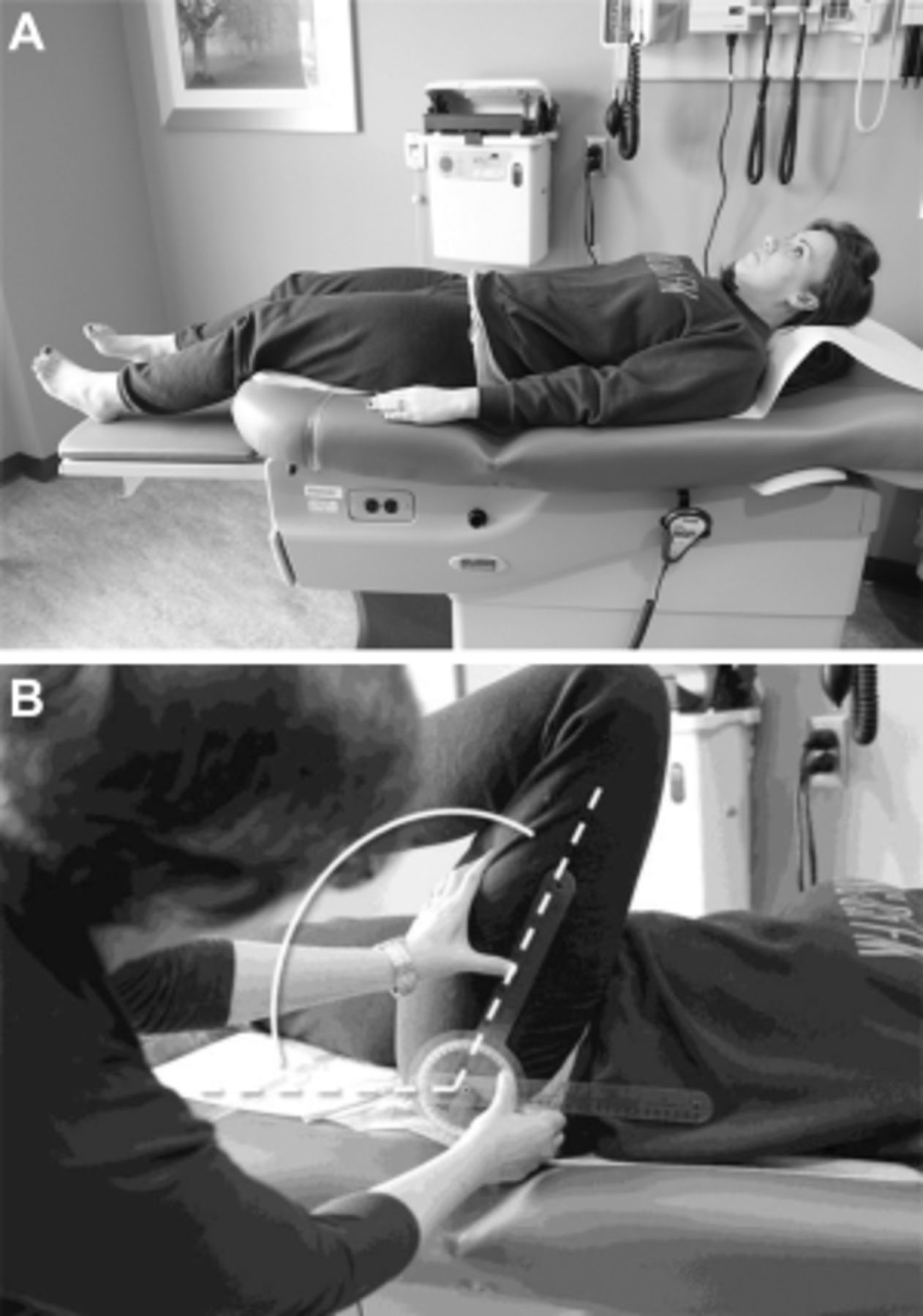

The patient presented has CLBP with hip OA being at least one contributor to his pain and difficulty functioning (Figure 1). The diagnosis of hip OA was made using a combination of clinical and radiographic criteria. [14] Because an estimated 50% or more older adults have radiographic evidence of hip OA that is asymptomatic [33], the expert panel that created the hip OA algorithm (Figure 1) felt that using American College of Rheumatology (ACR) clinical criteria (i.e., the first two bullets in the box at the top of the algorithm) to guide the performance of x-rays is essential. See Figures 3 A,B and 4 A,B illustrating the physical examination techniques for assessing hip internal rotation and hip flexion.

Figure 3.

A: Internal Hip Rotation: Seated patient at rest, her leg elevated with a pillow

to allow free movement about the femoral head.

B: Internal Hip Rotation: Using a goniometer, an examiner measures internal

hip rotation by placing the fulcrum on the patella, keeping the stationary arm

perpendicular to the floor, and the movement arm along the midline of the tibia

as she moves the foot as far away from the body as possible.

Figure 4.

A: Hip Flexion: supine patient at rest, waiting to be examined for hip flexion.

B: Hip Flexion: An examiner measures hip flexion with a goniometer on a

supine patient by positioning the fulcrum over the greater trochanter, the

stationary arm parallel with the patient's spine, and the movement arm

along the femur.

As shown in Figure 1, treatment recommendations should be developed in collaboration with the patient to understand his treatment goals and preferences and assess his pain severity. For patients with unrealistic treatment goals, for example, complete pain relief, education should immediately ensue. In keeping with the core tenets of chronic pain rehabilitation, an eye toward optimizing function in those with CLBP should be the primary goal of treatment [34, 35], thus pain reduction is a means to achieving that goal rather than a primary end point. Patients should expect, on average, 30% reduction in pain or 2 points on an 11 point (i.e., 010) scale. [15] For those with mild to moderate pain, we recommend conservative care that starts with weight loss for those overweight. [16] The MOVE!® Weight Management Program, designed by the VA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, is recommended specifically for patients who receive their care within Veterans Health Administration facilities. The ACR recommends cardiovascular and/or resistance land-based exercise, or aquatic exercise as part of the foundation of hip OA management. [16] Aquatic programs are especially useful for people unable to tolerate land-based exercise. [20] Prescription of an assistive device for joint unloading also should occur.

Pain interventions that from the patient's perspective are passive, such as injections, are themselves inadequate to provide lasting benefits. [3638] Patients who attend interdisciplinary pain management programs are taught to conceptualize these passive interventions as bridges to engaging in active pain self-management strategies [34, 35, 39], and that continued self-management will afford more robust benefits over time. Patients with hip OA as a contributor to their CLBP should be viewed similarly. The ACR recommends pain self-management conditionally because high quality evidence for the impact of pain self-management programs in reducing pain and improving function in older adults with hip OA is lacking, yet for patients with CLBP, active engagement in self-care is an important key to success. [16, 17]

What should be the role of pharmacological management? In keeping with the philosophy of chronic pain management articulated above, medication for older adults with hip OA and CLBP should be viewed as a means to an end (i.e., engaging in physical activity) rather than the end goal. Unless the patient has a contraindication, intra-articular hip injection for analgesia is an attractive option; in addition to the possibility of providing analgesia, it may help to ascertain the degree to which the hip itself is contributing to the patient's CLBP syndrome and associated disability. Note that the purpose of hip injection is to alleviate pain. If a patient has a contracted hip capsule and an associated flexion contracture, a hip injection will not treat the flexion contracture and its stress on the spine. In this situation, therefore, an injection may not be able to effectively ascertain the extent to which the hip is contributing to CLBP.

Guidelines for stepped care analgesia in the older adult with hip OA is provided in Table 2. In this table we include recommendations for starting doses and titration as well as dose-adjustments according to renal and hepatic function, and we highlight important drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in older adults. [21] Note that we include nonacetylated salicylates but not nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), in keeping with the 2012 Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medications for older adults. Celecoxib has many of the same deleterious effects as other NSAIDs and also is not recommended. [40] While the 2012 American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria do not include celecoxib as a contraindicated drug; the AGS 2009 Pain Guidelines recommend against its chronic use in older adults. [22] Opioids are not part of the 2012 AGS Beers Criteria. We include specific opioid prescribing recommendations in Table 2. Our list includes those opioids with the greatest evidence for a reasonable benefit/risk ratio in older adults. We do not include methadone because of its complicated and variable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. We believe that its prescription should be overseen by a pain specialist. Meperidine, which is on Beers list, has a metabolite with significant risk of neurotoxocity and should be avoided in older adults. [41] Note also that sustained release opioids should only be started in patients only after a short acting agent has been initiated and titrated to effect.

Insufficient research has been performed to strongly recommend any one complementary or alternative intervention over another for the management of pain related to hip OA. We recommend T'ai Chi as the first CAM modality that should be prescribed for older adults with hip OA because of strong evidence supporting its efficacy in preventing falls in older adults [27], which are an important consequence of chronic pain. [42] There also is evidence for the modest efficacy of T'ai Chi for reducing pain and improving function in older adults with hip OA. [28, 29] We highlight acupuncture because of the attention it has received regarding knee OA. Inadequate data exist to recommend for or against acupuncture for the treatment of hip OA. [30]

For patients with severe pain and mild to moderate degenerative disease on x-ray, it is important to make sure that all pain contributors have been identified. For example, does the patient have widespread pain and a clinical picture consistent with fibromyalgia? Is there depression, anxiety, or maladaptive coping? If so, these conditions should be treated simultaneously with treatment of the hip OA, as we will outline in future algorithms of this series. At the same time, the conservative care listed in Figure 1 and described above should be followed. If the patient has severe pain, advanced degenerative disease on x-ray, and no contraindications to surgery, THA should be considered. If such a patient is not a surgical candidate, a discussion about initiating opioids will likely occur. Part of this discussion must include education about the risk of falls and hip fracture [43, 44] and, therefore, the need to optimize mobility and stability prior to starting on these drugs. Preliminary data suggest that opioids may impair function in older adults with OA [45], thus the decision to start them must be accompanied by a frank discussion of their risks and that the main benefit is pain reduction, not improved function.

PT is recommended commonly for older adults with OA. While some data support the use of manual PT for patients with hip OA [46, 47], recent data fail to support its efficacy in reducing pain or improving function. [48] In our practice, we have found that teaching caregivers how to perform simple hip distraction techniques may be helpful for short term pain relief.

Resolution of Case

The patient had what Offierski classified as complex HSS, that is, symptoms from both the hip and spine without a clear single source of disability. In such patients, injection of the hip and/or the spine may help to target treatment. [2] Following intra-articular hip injection, our patient experienced complete elimination of his buttocks and leg pain, modest improvement in his LBP, and marked improvement in his functional status, supporting that a large part of the patient's disablement was related to his hip OA. The patient underwent an orthopedic surgery consultation and was scheduled for THA. In the course of his preoperative evaluation, he was found to have aortic stenosis and valve replacement was recommended prior to THA, which the patient declined. The patient continues to be active and manages his pain with oxycodone. He has been educated about the risk of falls and hip fracture associated with opioids in older adults. [43, 44] The risk-taking behavior that he describes is appropriate and he has not had any falls. He maintains realistic treatment expectations, focusing on his ability to function despite the persistence of some pain. Two years following initial Pain Clinic consultation, the patient continues to be functional and he is followed regularly by his primary care provider with as expected urine drug screen findings (i.e., presence of oxycodone and absence of nonprescribed drugs).

Summary

The lumbo-pelvic-hip complex should be considered as a unit when evaluating patients with CLBP. Because of the ubiquitous nature of imaging-identified degenerative spinal disease in older adults, examination of factors outside of the spine is critical in devising treatment strategies. Physical examination of the hips should occur routinely in these patients and when there is evidence of hip OA, x-rays should then be pursued to formalize diagnosis.

In the patient with complex HSS, that is, symptoms from pathology in both the hip and spine without a clear single source of disability, diagnostic blocks such as spinal and/or intra-articular injections may be helpful in identifying the main driver of disability. Given that these patients have chronic pain and multiple sites of pathology, realistic treatment expectations must be maintained.

Before starting oral analgesics in older adults, risks and benefits must be weighed carefully. Chronic NSAIDs, used commonly in younger patients, is not recommended for older adults. [21] This also is true for celecoxib. [22] Opioids are not without risk and prior to their initiation, falls risk should be assessed and minimized where possible with the help of a physical therapist and an assistive device. There is no evidence that opioids improve function in patients with chronic pain. This fact must be emphasized to patients before starting these medications. All other reasonable treatment options, including evaluating and treating other contributors to pain and disability, should be exhausted before opioids are considered.

Older adults with CLBP often have multiple physical contributors to their pain and difficulty functioning including an estimated one in four likelihood of hip OA. [11] Thorough physical assessment that includes examination of the hips is critical to optimize treatment outcomes. Doing so has the potential to save substantial costs and morbidity and optimize function and quality of life.

Key Points

Clinical evaluation of all older adults with CLBP should include evaluation (i.e., history and physical examination) of the hips.

X-rays should be used to formalize a diagnosis of hip OA, not to screen patients, as over half of pain-free older adults have radiographic evidence of degenerative hip disease.

Multimodal management that emphasizes non-pharmacological strategies and minimizes medications is preferred for older adults.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs used commonly for the treatment of hip OA in middle aged individuals should be avoided in older adults.

A decision to start opioids in older adults with hip OA and severe pain should be preceded by a discussion that highlights:

a. Opioids may be associated with a number of potential adverse effects. Older adults should be educated specifically about the increased risk of falls and hip fractures.

b. There is no evidence that opioids improve function, thus patients should recognize that their main purpose is for pain reduction.

c. All other options, including treating other contributors to pain and disability should clearly have been exhausted before a decision is made to start opioids.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service. The contents of this report do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. The author thanks Dave Newman, Dr. Rollin Gallagher, and Dr. Eric Rodriguez for their thoughtful review of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest:

The authors have indicated that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the content of this article.

References:

Wolfe F. Determinants of WOMAC function, pain and stiffness scores: Evidence for the role of low back pain, symptom counts, fatigue and depression in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:35561

Offierski C, Macnab I. Hip-Spine Syndrome spine. 1983;8(3):31621

Saito J, Ohtori S, Kishida S, et al. Difficulty of diagnosing the origin of lower leg pain in patients with both lumbar spinal stenosis and hip joint osteoarthritis. Spine 2012;37(25):208993

Redmond J, Gupta A, Hammarstedt J, Stake C, Domb B. The hip-spine syndrome: how does back pain impact the indications and outcomes of hip arthroscopy? Arthroscopy 2014;30(7):87281

Ben-Galim P, Ben-Galim T, Rand N, et al. The effect of total hip replacement surgery on low back pain in severe osteoarthritis of the hip. Spine 2007;32(19):2099102

Staibano P, Winemaker M, Petruccelli D, de Beer J. Total joint arthroplasty and preoperative low back pain. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:86771

Parvizi J, Pour A, Hillibrand A, et al. Back pain and total hip arthroplasty: A prospective natural history study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:132530

Hicks G, Morone N, Weiner D. Degenerative lumbar disc and facet disease in older adults: Prevalence and clinical correlates. Spine 2009;34:13016

Jarvik J, Hollingworth W, Heagerty P, Haynor D, Deyo R. The longitudinal assessment of imaging and disability of the back (LAIDBack) study: Baseline data. Spine 2001;26(10):115866

Inouye S, Studenski S, Tinetti M, Kuchel G. Geriatric syndromes: Clinical, research and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55(5):78091

Weiner D, Sakamoto S, Perera S, Breuer P. Chronic low back pain in older adults: prevalence, reliability, and validity of physical examination findings. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1120

Lesher J, Dreyfuss P, Hager N, Kaplan M, Furman M. Hip joint pain referral patterns: A descriptive study. Pain Med 2008;9(1):225

Weiner DK.

Deconstructing Chronic Low Back Pain in the Older Adult -

Shifting the Paradigm from the Spine to the Person

Pain Med 2015; 16 (5): 881885Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34(5):50514

Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole MR.

Clinical Importance of Changes in Chronic Pain Intensity

Measured on an 11-point Numerical Pain Rating Scale

Pain 2001 (Nov); 94 (2): 149-158Hochberg M, Altman R, April K, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(4):46574

Batterham S, Heywood S, Keating J. Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing land and aquatic exercise for people with hip or knee arthritis on function, mobility and other health outcomes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:123

Hadjistavropoulos T. Self-management of pain in older persons: helping people help themselves. Pain Med 2012;13(suppl 2):S6771

Buszewicz M, Rait G, Griffin M, et al. Self management of arthritis in primary care: Randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2006;333:87982

Krenzelok EP, Royal MA. ConfusionAcetaminophen dosing changes based on no evidence in adults. Drugs RD 2012;12(2):458

The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:61631

American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:133146

Finucane TE. Credulous fondness for celecoxib (letter). J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60(11):2190. (See also Semla TP, Fick DM. Response letter to Finucane. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60(11):219091)

Cepeda MS, Camargo F, Zea C, Valencia L. Tramadol for Osteoarthritis (Review). Cochrane Databse Syst Rev 2009. Available at: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com. Accessed December 1, 2014

Nuesch E, Rutjes AWS, Husni E, Welch V, Juni P. Oral or transdermal opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010. Available at: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com. Accessed December 1, 2014

Abou-Raya S, Abou-Raya A, Helmii M. Duloxetine for the management of pain in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: Randomized placebo-controlled trial. Age Ageing 2012;41:64652. Accessed December 1, 2014

Gillespie L, Robertson M, Gillespie W, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(9):CD007146

Wang C. Role of Tai Chi in the treatment of rheumatologic diseases. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2012;14:598603

Peng P. Tai Chi and chronic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012;37:37282

Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev; 2010;(1):CD001977

Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. The comparative safety of opioids for nonmalignant pain in older adults. Arch Intern Med 2010;170(22):197986

Buckeridge D, Huang A, Hanley J, et al. Risk of injury associated with opioid use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58(9):166470

Lane N, Nevitt M, Hochberg M, Hung Y, Palermo L. Progression of radiographic hip osteoarthritis over eight years in a community sample of elderly white women. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50(5):147786

Gatchel R, McGeary D, McGeary C, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: Past, present, and future. Am Psychol 2014;69(2):11930

Stanos S. Focused review of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs for chronic pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012;16:14752

Staal J, de Bie R, de Vet H, Hildebrandt J, Nelemans P. Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low back pain: An updated Cochrane review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34(1):4959

Haldeman S, Dagenais S.

A Supermarket Approach to the Evidence-informed Management of Chronic Low Back Pain

Spine Journal 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 17Mayer J, Haldeman S, Tricco A, Dagenais S.

Management of Chronic Low Back Pain in Active Individuals

Curr Sports Med Rep 2010 (Jan); 9 (1): 6066Ravenek M, Hughes I, Ivanovich N, et al. A systematic review of multidisciplinary outcomes in the management of chronic low back pain. Work 2010;35(3):34967

Juni P, Rutjes A, Dieppe P. Are selective COX 2 inhibitors superior to traditional non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs? BMJ 2002;324:128788 Erratum in: BMJ 2002;324:1538

Arnstein P. Balancing analgesic efficacy with safety concerns in the older patient. Pain Manage Nurs 2010;11:S1122

Patel K, Phelan E, Leveille S, et al. High prevalence of falls, fear of falling, and impaired balance in older adults with pain in the United States: Findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:184452

Huang A, Mallet L, Rochefort C, et al. Medication-related falls in the elderly: Causative factors and preventive strategies. Drugs Aging 2012;29(5):35976

O'Neil C, Hanlon J, Marcum Z. Adverse effects of analgesics commonly used by older adults with osteoarthritis: Focus on non-opioid and opioid analgesics. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2012;10(6):33142

Marcum Z, Zhan H, Perera S, et al. Predictors of disability and mortality risk in advanced knee OA. Pain Med 2014;15(8):133442

Hoeksma H, Dekker J, Ronday H, et al. Comparison of manual therapy and exericse therapy in osteoarthritis of the hip: a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51(5):7229

Abbott J, Robertson M, Chapple C, et al. Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: A randomized controlled trial. 1: clinical effectiveness. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:52534

Bennell K, Egerton T, Martin J, et al. Effect of physical therapy on pain and function in patients with hip osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311(19):198797

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Since 1-22-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |