Deconstructing Chronic Low Back Pain in the Older Adult -

Step by Step Evidence and Expert-Based Recommendations

for Evaluation and Treatment.

Part V: Maladaptive CopingThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Pain Medicine 2016 (Jan); 17 (1): 64–73 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Elizabeth A. DiNapoli, Michael Craine, Paul Dougherty, Angela Gentili,

Gary Kochersberger, Natalia E. Morone, Jennifer L. Murphy, Juleen Rodakowski,

Eric Rodriguez, Stephen Thielke, Debra K. Weiner

Mental Illness Research, Education & Clinical Center,

VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania Geriatric Research,

Education & Clinical Center,

VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Pittsburgh, PAOBJECTIVE: As part of a series of articles designed to deconstruct chronic low back pain (CLBP) in older adults, this article focuses on maladaptive coping-a significant contributor of psychological distress, increased pain, and heightened disability in older adults with CLBP.

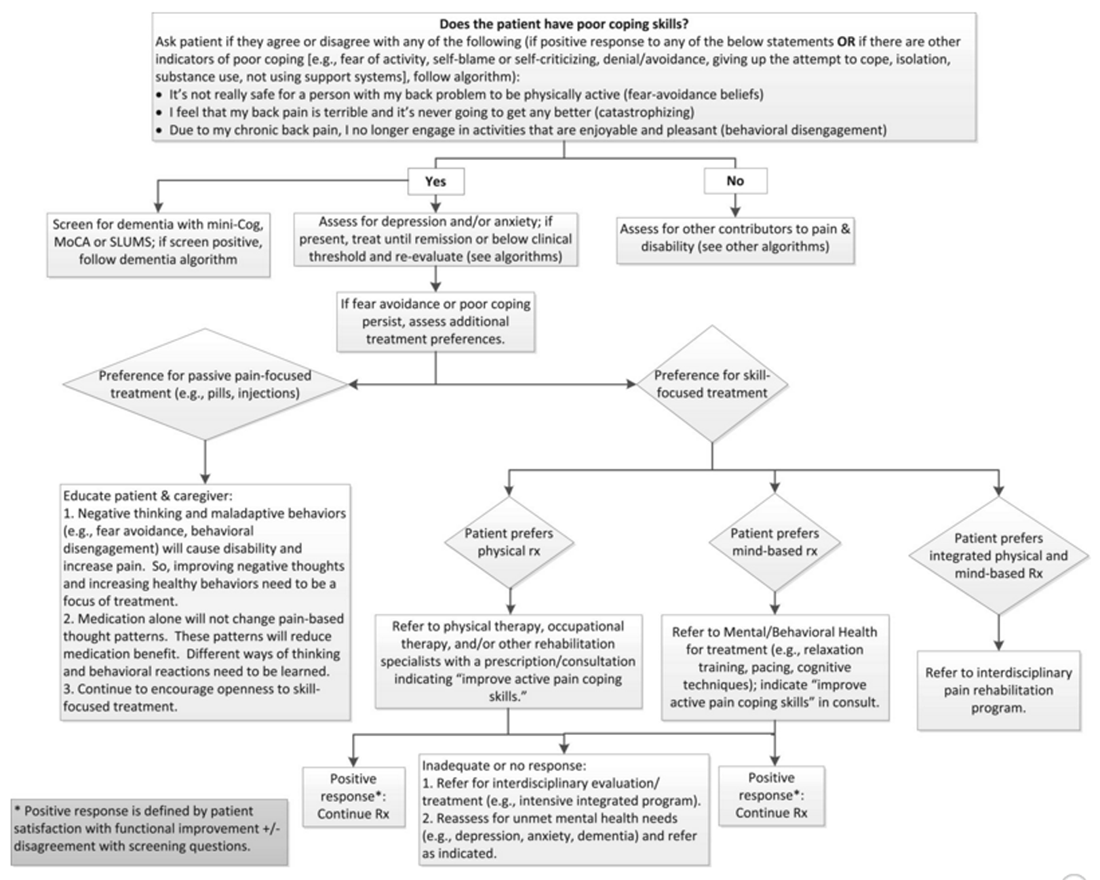

METHODS: A modified Delphi technique was used to develop a maladaptive coping algorithm and table providing the rationale for the various components of the algorithm. A seven-member content expert panel and a nine-member primary care panel were involved in the iterative development of the materials. While the algorithm was developed keeping in mind resources available within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities, panelists were not exclusive to the VHA, and therefore, materials can be applied in both VHA and civilian settings. The illustrative clinical case was taken from one of the contributors' clinical practice.

RESULTS: We present a treatment algorithm and supporting table to be used by providers treating older adults who have CLBP and engage in maladaptive coping strategies. A case of an older adult with CLBP and maladaptive coping is provided to illustrate the approach to management.

CONCLUSIONS: To promote early engagement in skill-focused treatments, providers can routinely evaluate pain coping strategies in older adults with CLBP using a treatment algorithm.

Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Academy of Pain Medicine. 2016. This work is written by US Government employees and is in the public domain in the US.

KEYWORDS: Aged; Assessment; Chronic Low Back Pain; Chronic Pain; Elderly; Low Back Pain; Maladaptive Coping; Primary Care

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Table 1 Older adults who experience chronic low back pain (CLBP) develop behavioral and cognitive coping strategies to tolerate or reduce pain. These coping strategies have been shown to significantly predict pain, functional capacity, and chronification of LBP. For example, adaptive coping strategies are generally associated with reduced pain, positive affect, and better psychological adjustment [1], whereas maladaptive coping strategies have been linked with negative outcomes such as psychological distress, increased pain, and heightened disability. [2–4] Please see Table 1 for examples of maladaptive and adaptive coping strategies. Research has found age-related differences in pain coping strategies across the life span. [5, 6] While older adults are more likely than younger adults to use a narrower range of pain-related coping strategies (e.g., less cognitive and more emotion-focused strategies), they tend to use these strategies more consistently and effectively. [7] As aging is associated with significant heterogeneity, many older adults with CLBP are at risk of engaging in maladaptive coping strategies. Fortunately, coping remains malleable with age, and maladaptive coping strategies can be effectively changed with interventions. [8, 9] Therefore, it is increasingly important for providers to assess pain coping strategies in this population.

The fear-avoidance model (FAM) is a theoretical model that describes how psychological factors affect the experience of pain and the development of chronic pain and disability. [10] Within the FAM, maladaptive coping is often characterized by helplessness or reliance on others and includes catastrophizing (i.e., exaggerated orientation toward pain stimuli and pain experience) [11, 12], fear-avoidance beliefs [13, 14], and behavioral disengagement. [15, 16] Patients with CLBP catastrophizing responses often create disproportionately strong fears about the potential for physical activities to produce pain or further harm the spine (i.e., fear-avoidance beliefs), reinforcing the original negative appraisal in a deleterious cycle. [10] It should be noted that fear-avoidance beliefs can occur concurrently with or independently of catastrophizing. Owing to these fear-avoidance beliefs, patients with CLBP may also decrease their engagement in activities that bring a sense of enjoyment, meaning, or accomplishment (i.e., behavioral disengagement). [17] Again, the use of maladaptive coping strategies (i.e., catastrophizing, fear-avoidance beliefs, and behavioral disengagement) has been shown to be associated with negative consequences in older adults, such as increased disability. [11–16] As such, CLBP treatment should emphasize teaching cognitive and behavioral skills to increase patients’ ability to cope with and manage pain. Fortunately, there are effective skill-focused treatments, such as physical therapy [18, 19] and psychotherapy [20–22], that emphasize adaptive coping strategies or an active approach to dealing with CLBP using techniques such as coping self-statements, re-interpreting pain sensations, and increasing activity level.

Cognitive and behavioral pain coping strategies have been found to be predictive of adjustment to chronic pain above and beyond what may be predicted on the basis of patient history variables (e.g., disability status, number of surgeries) and the tendency of patients to somaticize. [23] Therefore, to identify CLBP older adults in need of skill-focused treatments, clinicians must obtain a greater understanding of patients’ pain coping strategies.

In the clinical management of patients with CLBP, clinicians often assess for a number of demographic and medical status variables, but rarely are pain coping strategies routinely considered. One factor that may greatly limit clinicians’ comfort with assessing for psychosocial factors of CLBP, such as pain coping strategies, is that current assessment tools and treatment guidelines are too general and global. Treatment algorithms/guidelines help to minimize random variation in care, increase patient receipt of evidence-based care, and improve patient outcomes. [24, 25] With an algorithm to guide the management of maladaptive coping strategies in older adults with CLBP, clinicians may not only help promote early engagement in skill-focused treatments aimed at increasing positive coping strategies but, in turn, also reduce pain, decrease emotional distress, and increase functionality. The purpose of this paper is to present a treatment algorithm for clinicians treating older adults with CLBP who engage in maladaptive coping strategies. We will also present an older adult patient who has CLBP with maladaptive coping and describe the approach to the management and resolution of the case.

Methods

Figure 1 As per the detailed description provided in the series overview [26], a modified Delphi technique involving a content expert panel and primary care review panel was used to create the maladaptive coping algorithm (Figure 1) and a table providing the rationale for the various components of the algorithm (Table 2). The PI (DW) drafted an evidence-based treatment algorithm and supportive tables based on a comprehensive review of the literature and general clinical utility when strong evidence was not yet available. The algorithm and accompanying table were then refined by an expert panel. Expertise represented by the seven Delphi expert panel members included geriatric medicine, geriatric pharmacology, geriatric psychology, and occupational therapy.

Table 2.

Maladaptive coping: theoretical and pragmatic underpinnings of algorithm recommendations

Algorithm component Comments References Role of fear avoidance in CLBP Fear of activity is an important contributor to disability in older adults.

Previous studies have validated the FAB questionnaire; however, for the purpose of this study we have utilized a single question (taken from the 2014 NIH Task Force on Research Standards for chronic Low Back Pain) to practically assess fear avoidance that is generalizable to a clinical setting.1. Camacho-Soto A, Sowa GA, Perera S, Weiner DK. Fear avoidance beliefs predict disability in older adults with chronic low back pain. PM R 2012;4(7):493–7.

2. Sions JM, Hicks GE. Fear-avoidance beliefs are associated with disability in older American adults with low back pain. Phys Ther 2011;91(4):525–34.

3. Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, et al. Report of the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain

Journal of Pain 2014 (Jun); 15 (6): 569–585

4. Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U, et al. Fear-avoidance beliefs- a moderator of treatment efficacy in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2014;14(11):2658–78.Role of catastrophizing in CLBP Pain catastrophizing is negative and distorted thinking and worrying about the pain and one's inability to cope. Catastrophizing has also been shown to influence LBP-related disability in middle-aged patients.

The catastrophizing subscale of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ) has been previously validated; however, for the purpose of this study we have utilized a single question (taken from the 2014 NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain) to assess coping that is generalizable to a practical clinical setting.1. Morone NE, Karp JF, Lynch CS, et al. Impact of chronic musculoskeletal pathology on older adults: A study of differences between knee OA and low back pain. Pain Med 2009;10(4):693–701.

2. Wertli MM, Eugster R, Held U, et al. Catastrophizing- a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2014;14:2639–57.

3. Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: A critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:745–58.Role of behavioral disengagement in CLBP Unwillingness to remain active predicts poor outcomes in CLBP. Active interventions are considered a mainstay of pain treatment. 1. Hall AM, Kamper SJ, Maher CG, et al. Symptoms of depression and stress mediate the effect of pain on disability. Pain 2011;152(5):1044–51.

2. Basler, HD, Jakle C, Kroner-Herwig B. Incorporation of cognitive-behavioral treatment in the medical care of chronic low back patients: A controlled randomized study in German pain treatment centers. Patient Education and Counseling 1997;31(2):113–24.

3. Van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: A systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine 2000; 25(20):2688–99.Screening for dementia Patients with dementia, because of difficulty putting pain into context, may have difficulty with pain coping. 1. Farrell MJ, Katz B, Helme RD. The impact of dementia on the pain experience. Pain 1996; 67(1):7–15.

2. Jamison RN, Sbrocco T, Parris WC. The influence of problems with concentration and memory on emotional distress and daily activities in chronic pain patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 1988;18:183–91.Screening for depression and anxiety Depression occurs commonly with maladaptive pain coping strategies. 1. Keefe FJ, Williams DA. A comparison of coping strategies in chronic pain patients in different age groups. J Gerontol 1990;45(4):P161–5.

Anxiety and fear commonly overlap. 2. McCracken LM, Gross RT. Does anxiety affect coping in chronic pain? The Clinical Journal of Pain 1993;9:253–9. Role of psychoeducation for patients and caregivers Patients and families often have misunderstandings about CLBP and its treatments.

Education about CLBP can improve pain management as part of a comprehensive biopsychosocial approach.1. Engers AJ, Jellema P, Wensing M, et al. Individual patient education for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 1.

2. Burton AK, Waddell G, Tillotson M, Summerton N. Information and advice to patients with back pain can have a positive effect: A randomized controlled trial of a novel educational booklet in primary care. Spine 2009;24:2484–91.Skill-focused treatment Recent treatment guidelines recommend that for patients who do not improve with self-care options, clinicians should consider the addition of other treatment options including:

- Exercise therapy

- Yoga

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Progressive relaxation

1. Chou R, Huffman LH, American Pain Society, American College of Physicians. Nonpharma-cologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2007;147(7):492–504.

Interdisciplinary rehabilitation (also called multidisciplinary therapy): an intervention that combines and coordinates physical, vocational, and behavioral components and is provided by multiple health care professionals with different clinical backgrounds.

The intensity and content of interdisciplinary therapy varies widely.1. Gregg CD, Hoffman CW, Hall H, McIntosh G, Robertson PA. Outcomes of an interdisciplinary rehabilitation programme for the management of chronic low back pain. J Prim Health Care 2011;3(3):222–7.

2. Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015;18:350–444.

3. Cassidy EL, Atherton RJ, Robertson N, Walsh DA, Gillett R. Mindfulness, functioning and catastrophizing after multidisciplinary pain management for chronic low back pain. Pain 2012;153(3):644–50.

Physical Rx: Physical therapy alone

can improve pain coping strategies.1. Bunzli S, Gillham D, Esterman A. Physiotherapy-provided operant conditioning in the management of low back pain disability: A systematic review. Physiother Res Int. 2011; 16(1):4–19.

2. Evans S, Sternlieb B, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK. Using the biopsychosocial model to understand the health benefits of yoga. J Complement Integr Med 2009;6(1):1–22.

Mind-based Rx: A variety of mind-based strategies can improve pain

coping strategies.1. McCracken LM. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatment for chronic pain: Outcome, predictors of outcome, and treatment process. Spine 2002;27:2564–73.

2. Ostelo RW, van Tulder M W, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. The Cochrane Library 2005

3. Eccleston C, Morley SJ, Williams AC. Psychological approaches to chronic pain management: Evidence and challenges. Br J Anaesth 2013;111(1):59-63.

4. Morone NE, Greco CM, Weiner DK. Mindfulness mediation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: A randomized controlled pilot study. Pain 2008;134(3):310–19.

5. Esmer G, Blum J, Rulf J, Pier J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for failed back surgery syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110(11):646–52.

6. Schutze R, Slater H, O’SullivanP, et al. Mindfulness-based Functional Therapy: A preliminary open trail of an integrated model of care for people with persistent low back pain. Front Psychol 2014;5:839–48.

Case Presentation

Relevant History

The patient is a 69–year-old white male who has been divorced once and married to his current wife for 20+ years, is retired, and has brittle type I diabetes. He has had five lumbar surgeries. The patient showed initial improvement from each surgery but then had worsening low back and leg pain after a fall, which he believes was related to low blood sugar. He describes worry about further injury. The patient has not had physical therapy recently but received such services in the past after surgery. He failed epidural steroid injections, facet injections, and medial branch block and declined radio frequency ablation. The patient is taking bupropion SA 150 mg every 12 hours for mood with some benefit and 200 mg of trazodone for insomnia. His analgesic regimen includes oxycodone 10 mg every 6 hours, fentanyl 50 mcg every 72 hours, and gabapentin 900 mg three times a day. The patient complains of low energy.

Pain Presentation

The pain is described as sharp and stabbing, rated at 8 to 10/10 on a Numeric Rating Scale. He has often expressed that his pain is greater than 10. The main pain location is the axial lumbosacral junction with radiation into the bilateral anterior and posterior thighs (left greater than right). The pain is better when lying down with left leg elevation (i.e., placing a pillow under the knee while supine) and with analgesics and is worse with walking more than one block, bending, twisting, lifting, and “any activity that lasts for more than 5 minutes.”

Assessment of Coping Style

Through a clinical interview, the patient described the constructs of catastrophizing, fear-based avoidance, and behavioral disengagement. He endorsed a pattern of catastrophizing: “I don’t think that this will ever get better. It will only get worse. A lot of the time it is unbearable.” In addition, he provided many examples of disengaging from enjoyable, meaningful activities, such as working in his garden, because he believed that physical activity might harm his back and worsen his pain (i.e., fear-avoidance beliefs).

He also reports feeling angry and disgusted much of the time and often retreats to a dark room.

Physical Examination

The following aspects are notable in the patient’s physical examination.GENERAL: No acute distress.

MOOD/AFFECT: Sad, mildly irritable, and tearful at times.

GAIT: Antalgic, slightly wide based with shortened step length. Able to briefly toe-and-heel walk limited by back pain without instability.

HIPS: Internal and external range of motion within normal limits without pain at end range bilaterally. Hip scour (i.e., manipulating the joint to look for “clicks” or “chunks”) negative bilaterally. No tenderness over greater trochanter.

LOW BACK: Normal muscle bulk without asymmetry; well-healed surgical scar. Tenderness to palpation is diffuse without focal point tenderness reproducing symptoms. Palpation of the right mid-lumbar paraspinal process caused left leg numbness but no trigger point/nodule. Range of motion is moderately pain limited in all planes with guarding and minimal extension/rotation with guarding. Straight leg raise is negative bilaterally sitting and supine.

FABER: Negative on the left and right. Piriformis Test, a standard provocative muscle test to see whether a tight piriformis is stimulating sciatic pain, is negative on the left and right. Popliteal angle mildly reduced.

NEUROLOGICAL: Motor: 5/5 in all myotomes of the bilateral upper extremities except as pain limited. Three toe raises left and five toe raises right, but limited by pain. Extensor halluces longus (i.e., the muscle that extends the big toe) and dorsiflexion of the foot are 4/5 bilateral, otherwise 5/5 in all myotomes of the bilateral lower extremities, except as pain limited.

REFLEXES: Biceps, brachioradialis, triceps, patellar, Achilles 2+ bilaterally.Imaging

Lumbar MRI revealed multilevel lumbar spondylosis with laminectomies (L4–5 and L5–S1) without fusion. No areas of residual moderate or severe stenosis.

Approach to Management

The patient presented was told that his CLBP was caused by multilevel degenerative disc disease with lumbar and cervical spondylosis complicated by chronic stress and diabetes. In addition, his maladaptive coping contributes to his pain and difficulty functioning. To help clinicians assess for maladaptive coping in patients with CLBP, the algorithm provides three statements targeting fear-avoidance beliefs, catastrophizing, and behavioral disengagement. Clinicians can also assess for coping strategies with widely available instruments, such as the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [27], Survey of Pain Attitudes–Revised (SOPA-R) [28], Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) [29], and Coping Strategies Questionnaire–Revised (CSQ-R). [30]

Depression and anxiety are related to engagement in maladaptive pain coping strategies [31, 32], but the patient screened negative for these disorders. Widely accessible depression and anxiety screening instruments include the Patient Health Questionnaire- 9 (PHQ-9) [33] and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7). [34] Dementia is also associated with maladaptive coping responses [35, 36] but the patient screened negative for cognitive impairment on the St. Louis University Mental Status Examination (SLUMS) [37], and the index of suspicion for cognitive impairment clinically was low, so no further testing was performed. In other articles in this series, we provide guidance on a clinical approach to the older adult with CLBP and anxiety, depression, or dementia.

As shown in the algorithm (Figure 1), treatment recommendations should be guided by patient–provider collaboration with an understanding of the patient’s treatment goals and preferences. Patients with CLBP who actively engage in self-management have been shown to have superior outcomes compared with those who take a passive approach. [38] For patients who prefer a passive pain-focused treatment or treatment that is performed by someone other than the patient (e.g., chiropractic adjustment, medication, injections), clinicians should educate the patient (and caregiver when appropriate) about 1) the association between maladaptive coping and disability/pain; 2) how medication will not fix maladaptive coping and how such coping strategies will reduce medication benefits; and 3) skill-focused treatments. Recent treatment guidelines recommend that for patients with CLBP who do not improve with self-care options, clinicians should consider the addition of other skill-focused treatments. [39] There is strong evidence supporting physical (e.g., physiotherapist-provided operant conditioning or yoga) and mind-based treatments (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy or mindfulness-based treatments) for maladaptive coping (Table 1). Another option for patients with CLBP with maladaptive coping is to be referred to an interdisciplinary team-based pain rehabilitation program that includes physical, vocational, and behavioral components. [40, 41] The authors acknowledge that interdisciplinary team-based pain rehabilitation programs may not be available to the provider/patient. The American Chronic Pain Association provides additional resources that may be helpful to providers practicing in resource-challenged areas (see http://theacpa.org/).

Resolution of Case

The previously described patient declined a new referral for physical therapy, stating that it only helped for a while in the past. He also reported that he was concerned about increasing his pain from physical therapy. The patient inquired about additional surgery and injections, but when advised that these would likely not provide benefit, he stated that he would be interested in learning mind-based pain management skills. He reported that this stemmed from a positive response he had from group therapy for depression. The patient was referred to a standard 10-week cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) group specific for pain supplemented by some components of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). [42]

The patient completed and responded well to the CBT group. He reported daily use of breathing-relaxation techniques. He also reported improved anger management through the use of cognitive awareness and attention to patterns of negative thoughts. Specifically, he demonstrated awareness of the link between pain flares and increased anger. He reported that although he still feels angry about hurting, he does not become mean or irritated with others as he once did. The patient’s wife also noted a decrease in his irritability. In the CBT group, the patient set specific behavioral SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time sensitive) goals. The patient’s SMART goals involved walking more, doing some yardwork, participating in household chores, and going on another elk hunting trip with his friends (something he had not done for several years). He accomplished this hunting trip, which he determined would be his last owing to other health concerns. While he did not hunt, he did chores around the camp, and he was pleased about his participation. The patient also learned to use the skill of pacing by inserting timed rest breaks to increase his walking to two blocks without significantly increasing his pain. Despite initial hesitation, the patient also engaged in a re-trial of physical therapy and learned a home exercise program that he performs somewhat sporadically several times a week. He said this helped enable him to do some yardwork, but, owing to an ongoing tendency to overdo it, he remains somewhat guarded about physical activity.

Consistent with a model of relapse prevention [43], the patient continued in a twice-per-month support group that focused on the application of adaptive coping skills to pain management and stressors. He has increased his time spent reading, an activity he finds pleasant and enjoyable. He provides support to other members of the group and reports this to be a rewarding and meaningful experience. He has also had a 75% reduction in fentanyl (50 mcg every 72 hours to 12.5 mcg every 72 hours) and 25% reduction in oxycodone (10 mg every 6 hours to 10 mg every 8 hours). The patient reported that this medication reduction has helped improve his energy and concentration. He has also successfully refrained from increasing oxycodone when experiencing pain flares, especially related to weather changes, as he now has other active coping skills that he is able to implement. Rather than depending on external interventions, he stated it helps him to maintain hope that healthcare technology will provide some additional relief for him in the future “if I can just hang in there using what I know.” The patient is now able to recognize the importance of hope versus catastrophizing and how this helps him effectively cope with pain. The patient had a positive response to treatment as defined by his satisfaction with functional improvement and no longer endorsing maladaptive coping skills (i.e., fear-avoidance beliefs, catastrophizing, and behavioral disengagement).

Summary

Maladaptive cognitive and behavioral pain coping strategies are associated with negative patient outcomes and have been found to be predictive of adjustment to chronic pain. Therefore, it is paramount that clinicians routinely assess for pain coping strategies as a way to identify patients with CLBP in need of skill-focused treatments. The goal of the presented treatment algorithm is to provide an evidence-based decision aid that integrates patient preferences for clinicians to use in the shared treatment decision-making process.

Older adults with CLBP commonly exhibit increased levels of emotional and cognitive distress. In addition, patients with CLBP engaging in maladaptive coping strategies are at increased risk for having co-occurring mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and dementia. Given the complexity of such patients, it is important that clinicians assess and treat mental health conditions adequately before engaging the patient in skill-focused treatments aimed at increasing positive coping strategies.

Given that the treatment decision is guided by patient preferences, it is important that patient education be implemented for those with unrealistic treatment goals. In keeping with the core tenets of chronic pain rehabilitation, the general goals of treatment should be optimizing function and reducing engagement in maladaptive coping skills. Individual goals should reflect specific and reasonable objectives that are motivating and meaningful to the patient.

Key Points

Clinical evaluation of all older adults with CLBP should include accessing patients’ pain coping strategies.

Maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., catastrophizing, fear-avoidance beliefs, and behavioral disengagement) have been linked with negative outcomes such as increased pain and heightened disability.

Treatment algorithms to guide the management of maladaptive coping strategies in patients with CLBP can help to increase patient engagement in skill-focused evidence-based treatments.

Depression, anxiety, and dementia may entail maladaptive coping strategies; separate treatment algorithms are available for each of these disorders.

Treatment recommendations should be guided by collaboration with the patient to understand his/her treatment goals and preferences. Treatment options include:

a. Passive pain-focused treatments (e.g., medication, injections). If the patient prefers this approach, (s)he should be educated to encourage openness to skill-focused treatment.

b. Skill-focused treatments (e.g., physical therapy, psychotherapy)

c. Integrated-pain and skill-focused treatments

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dave Newman for his assistance with this project.

Funding sources:

This material is based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service.

Disclosure and conflicts of interest:

The contents of this report do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Academy of Pain Medicine. 2016. This work is written by US Government employees and is in the public domain in the US.

References:

Smith JA, Lumley MA, Longo DJ.

Contrasting emotional approach with passive coping for chronic myofascial pain.

Ann Behav Med 2002;24(4):326–35Snow-Turek AL, Norris MP, Tan G.

Active and passive coping strategies in chronic pain patients.

Pain 1996;64(3):455–62Wertli MM, Eugster R, Held U, et al.

Catastrophizing-a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with low back pain: A systematic review.

Spine J 2014;14(11):2639–57Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U, et al.

Fear-avoidance beliefs-a moderator of treatment efficacy in patients with low back pain: A systematic review.

Spine J 2014;14(11):2658–78Watkins KW, Shifren K, Park D, Morrell R.

Age, pain, and coping with rheumatoid arthritis.

Pain 1999;82:217–28Molton I, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, et al.

Coping with chronic pain among younger, middle-aged, and older adults living with neurological injury and disease.

J Aging Health 2008;20(8):972–96Molton IR, Terrill AL.

Overview of persistent pain in older adults.

Am Psychol 2014;69(2):197–207Keefe FJ.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for managing pain.

Clin Psychol 1996;49(3):4–5Regier NG, Parmelee PA.

The stability of coping strategies in older adults with osteoarthritis and the ability of these strategies to predict changes in depression, disability, and pain.

Aging Mental Health 2015;19(12):1113–22Linton SJ, Shaw WS.

Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain.

Phys Ther 2011;91(5):700–11Morone NE, Karp JF, Lynch CS, et al.

Impact of chronic musculoskeletal pathology on older adults: A study of difference between knee OA and low back pain.

Pain Med 2009;10(4):693–701Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR.

Pain catastrophizing: A critical review.

Expert Rev Neurother 2009;9(5):745–58Camacho-Soto A, Sowa GA, Perera S, Weiner DK.

Fear avoidance beliefs predict disability in older adults with chronic low back pain.

Pm R 2012;4(7):493–7Sions JM, Hicks GE. Fear-avoidance beliefs are associated with disability in older American adults with low back pain. Phys Ther 2011;91(4):525–34

Hall AM, Kamper SJ, Maher CG, et al.

Symptoms of depression and stress mediate the effect of pain on disability.

Pain 2011;152(5):1044–51Van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JW, et al.

Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: A systematic review within the framework of the Cochran Back Review Group.

Spine 2000;25(20):2688–99Lewinsohn PM, Graf M.

Pleasant activities and depression.

J Consult Clin Psychol 1973;41(2):261–8Bunzli S, Gillham D, Esterman A.

Pysiotherapy-provided operant conditioning in the management of low back pain disability: A systematic review.

Physiother Res Int 2011;16(1):4–19Evans S, Sternlieb B, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK.

Using the biopsychosocial model to understand the health benefits of yoga.

J Complement Integr Med 2009;6(1):1–21Eccleston C, Morley SJ, Williams AC.

Psychological approaches to chronic pain management: Evidence and challenges.

Br J Anaesth 2013;111(1):59–63Esmer G, Blum J, Rulf J, Pier J.

Mindfulness-based functional therapy: A preliminary open trial of an integrated model of care for people with persistent low back pain.

Front Psychol 2014;5:839Ostelo RW, Van Tulder MW, Vlaeyen JW, et al.

Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain.

Cochrane Lib 2005; doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002014.pub2Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ.

The use of coping strategies in chronic low-back-pain patients- relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment.

Pain 1983;17(1):33–44Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, et al.

Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines.

BMJ 1999;318(7182):527–30AM, DuPen AR, Ersek M.

The use of algorithms in assessing and managing persistent pain in older adults.

Am J Nurs 2011;111(3):34–43Weiner DK.

Deconstructing Chronic Low Back Pain in the Older Adult -

Shifting the Paradigm from the Spine to the Person

Pain Med 2015; 16 (5): 881–885Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J.

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation.

Psychol Assess 1995;7(4):524–32Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM.

Pain belief assessment: A comparison of the short and long versions of the survey of pain attitudes.

J Pain 2000;1:138–50Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, et al. A

Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability.

Pain 1993;52:157–68Riley J, Robinson ME. CSQ:

Five factors or fiction?

Clin J Pain 1997;13:156–62Keefe FJ, Williams DA.

A comparison of coping strategies in chronic pain patients in different age groups.

J Gerontol 1990;45(4):161–5McCracken LM, Gross RT.

Does anxiety affect coping in chronic pain?

Clin J Pain 1993;9:253–9Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB.

The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure.

J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606–13Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B.

A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7.

Arch Intern Med 2006;166(10):1092–7Farrell MJ, Katz B, Helme RD.

The impact of dementia on the pain experience.

Pain 1996;67(1):7–15Jamison RN, Sbrocco T, Parris WC.

The influence of problems with concentration and memory on emotional distress and daily activities in chronic pain.

Int J Psychiatry Med 1988;18:183–91Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al.

Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder: A pilot study.

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14(11):900–10Oliveira VC, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, et al.

Effectiveness of self-management of low back pain: Systematic review with meta-analysis.

Arthritis Care Res 2012;64(11):1739–48Chou R, Huffman LH; American Pain Society.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society/

American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 492–504Gregg CD, Hoffman CW, Hall H, McIntosh G, Robertson PA.

Outcomes of an interdisciplinary rehabilitation programme for the management of chronic low back pain.

J Prim Health Care 2011;3(3):222–7Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al.

Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMJ 2015;350(18):444Hayes SC, Lillis J.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012Turk DC, Rudy TE.

Neglected topics in the treatment of chronic pain patients – relapse, noncompliance, and adherence enhancement.

Pain 1991;44:5–28

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Since 1-22-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |