Development of an Evidence-Based Practical Diagnostic Checklist

and Corresponding Clinical Exam for Low Back PainThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 665–676 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Robert D. Vining, DC, DHSc, Amy L. Minkalis, DC, MS, Zacariah K. Shannon, DC, MS, Elissa J. Twist, DC, MS

Palmer Center for Chiropractic Research,

Davenport, Iowa.

robert.vining@palmer.edu

Thanks to JMPT for permission to reproduce this Open Access article!

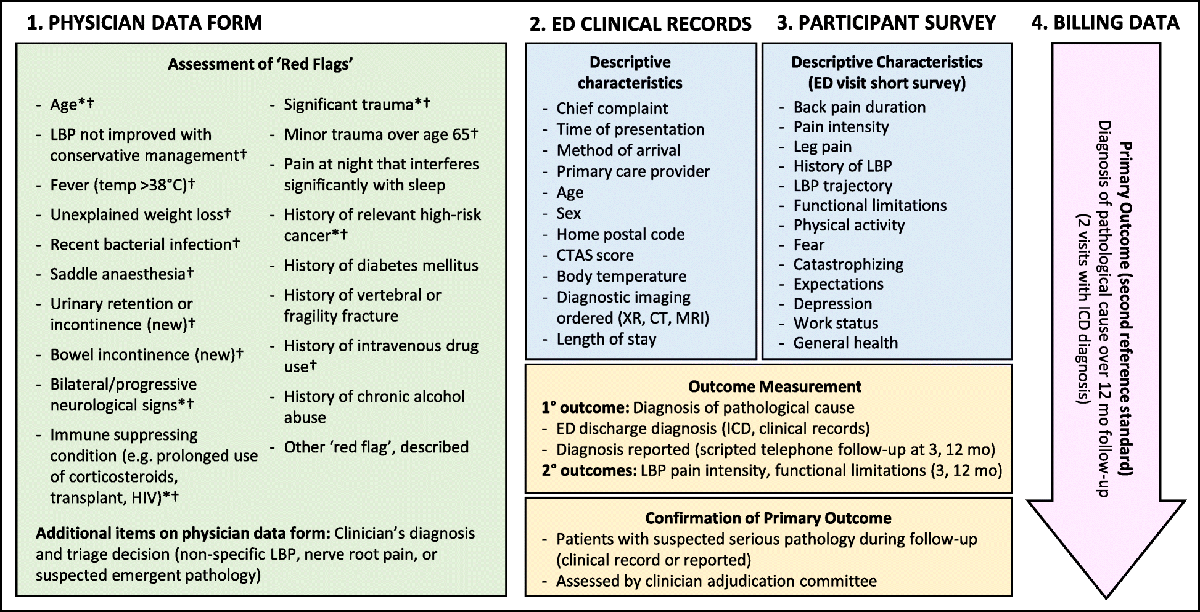

FROM: Diagn Progn Res 2019OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to use scientific evidence to develop a practical diagnostic checklist and corresponding clinical exam for patients presenting with low back pain (LBP).

METHODS: An iterative process was conducted to develop a diagnostic checklist and clinical exam for LBP using evidence-based diagnostic criteria. The checklist and exam were informed by a systematic review focused on summarizing current research evidence for office-based clinical evaluation of common conditions causing LBP.

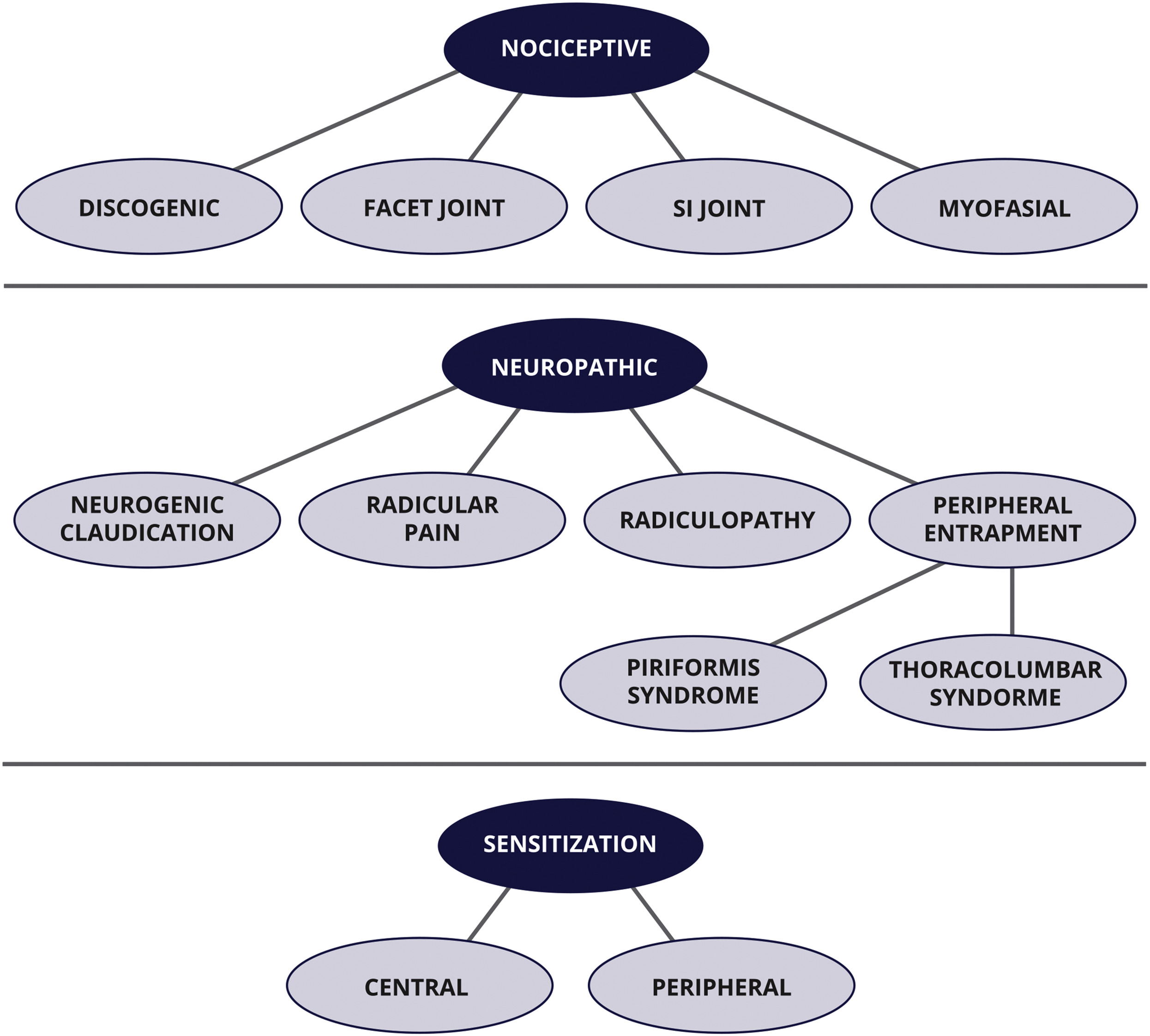

RESULTS: Diagnostic categories contained within the checklist and exam include nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain, and sensitization. Nociceptive pain subcategories include discogenic, myofascial, sacroiliac, and zygapophyseal (facet) joint pain. Neuropathic pain categories include neurogenic claudication, radicular pain, radiculopathy, and peripheral entrapment (piriformis and thoracolumbar syndrome). Sensitization contains 2 subtypes, central and peripheral sensitization. The diagnostic checklist contains individual diagnostic categories containing evidence-based criteria, applicable examination procedures, and checkboxes to record clinical findings. The checklist organizes and displays evidence for or against a working diagnosis. The checklist may help to ensure needed information is obtained from a patient interview and exam in a variety of primary spine care settings (eg, medical, chiropractic).

CONCLUSION: The available evidence informs reasonable working diagnoses for many conditions causing or contributing to LBP. A practical diagnostic process including an exam and checklist is offered to guide clinical evaluation and demonstrate evidence for working diagnoses in clinical settings.

KEYWORDS: Diagnosis; Evidence-Based Practice; Low Back Pain; Systematic Review

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

The act of diagnosis involves investigating, critically analyzing, and identifying characteristics and causes of disease and distinguishing conditions by name. [1, 2] An evidence-based diagnostic process for low back pain (LBP) should answer 3 fundamental questions [3, 4]:(1) Are the symptoms with which the patient is presenting reflective of a visceral disorder or a serious or potentially life-threatening disease?

(2) From where is the patient’s pain arising?

(3) What has gone wrong with this person as a whole that would cause the pain experience to develop and persist?In answering these questions, practitioners are faced with 3 differing viewpoints.

Viewpoint 1: Seeking a Specific Diagnosis Is Largely Futile

Commonly, LBP cannot be definitively diagnosed. Factors that impede definitive diagnosis include(1) the absence of gold-standard tests that definitively confirm or rule out specific conditions [5];

(2) the potential for multiple, simultaneously occurring conditions to produce overlapping symptoms [6];

(3) the potential for psychosocial components to negatively influence symptom perceptions, perpetuation, or the ability to cope [7]; and

(4) limited understanding of causal mechanisms. [6, 8]The ambiguity surrounding diagnosis leads practitioners and researchers to use nondescript terms, such as nonspecific LBP, mechanical LBP, and idiopathic LBP. [9] Although these terms acknowledge the diagnostic uncertainty associated with LBP, they do not require or provide a critical analysis of a problem, identify distinguishing characteristics, offer an explanation, help patients understand symptoms, or inform management decisions for either patients or practitioners.

Viewpoint 2: Practitioners Should Identify Select Conditions

Current clinical guidelines recommend limited diagnostic approaches for LBP. The American College of Physicians recommends separating LBP diagnoses into 3 categories:(1) nonspecific LBP,

(2) LBP of radicular origin and spinal stenosis, and

(3) LBP caused by pathology (eg, malignancy) or other visceral source (eg, renal, infection, abdominal aortic aneurysm). [10]The United States Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense clinical practice guideline recommends identifying radiculopathy, neurogenic claudication, serious underlying pathology, and psychosocial factors causing or contributing to LBP. [11] Nijs et al recommend using evidence-based methods to distinguish between nociceptive and neuropathic pain, or pain augmented through central sensitization mechanisms. [12] Bussieres et al recommend triaging patients into 1 of 3 categories: specific LBP, nonspecific LBP, and back and leg pain/sciatica. [13] Globe et al, in a separate guideline, recommend identifying radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication. [14]

Table 1 Guideline recommendations to identify select diagnoses exist because some conditions are known or thought to require distinct management approaches. However, limited diagnostic approaches raise important questions, such as: Which conditions should practitioners identify when guidelines disagree? How can guideline-recommended diagnoses be identified without differentiating conditions known to cause similar symptoms and for which scientific study has produced evidence to support a working diagnosis? Following any limited diagnostic strategy has the practical effect of demanding differential diagnosis of other conditions. For example, pain radiating to the lower extremity requires discriminatory evaluation to determine whether symptoms likely represent pain of radicular or vascular origin, or sclerotogenous pain referred from tissues such as the intervertebral disc. [15–18] Each of these example conditions presumably require different clinical management. [19, 20] Likewise, discriminating radicular pain from radiculopathy (see definitions listed in Table 1) is needed to inform disparate management strategies: conservative care for radicular pain versus possible surgical decompression to spare nerve root function for radiculopathy. [23–26]

Viewpoint 3: Practitioners Should Seek a Working Diagnosis

Working diagnoses are hypotheses that inform clinical management by balancing the degree of confidence in a working diagnosis against treatment risks or withholding care. [27] Working diagnoses are inherently flexible, designed to change as new information is obtained (eg, treatment response or when symptoms change). [27] Establishing a working diagnosis allows the possibility of error and thus requires continual critical analysis to explain and understand symptoms and treatment response, and to justify ongoing management decisions.

Working diagnoses can inform initial and follow-up management strategies. [27] Without a working hypothesis, decisions about care are more likely to be arbitrarily informed. Working diagnoses can also foster better communication among health professionals and with patients through universally understood terminology. Using working diagnoses can potentially reduce patient isolation by facilitating social support through connection with others suffering from similar conditions. [28, 29] Patient education about a condition can help reduce anxiety and excessive health care seeking while facilitating informed consent, self-efficacy, and self-management activities. [30–32] However, education is severely limited when diagnoses describe nothing more than symptoms (eg, nonspecific LBP, mechanical LBP). [28]

There exists a large body of research reporting studies of in-office diagnostic methods for conditions causing LBP. [33] However, there are currently few practical tools that incorporate a synthesis of available evidence to guide practitioners in systematic clinical examination and in determining the relative strength of working diagnoses. Such tools may facilitate the application of scientific evidence into practical clinical environments.

The purpose of this study was to use scientific evidence to develop a practical diagnostic checklist and corresponding clinical exam for patients presenting with LBP.

The present article proposes a pragmatic office-based exam and diagnostic checklist, describes key elements to efficiently conduct the proposed exam, and addresses practical considerations for how to value the relative strength of working diagnoses.

Methods

As previously described, a systematic review was conducted to evaluate and summarize current evidence for diagnosis of common conditions causing LBP and to propose standardized terminology use. [33]

Findings from the systematic review were used to create the evidence-based diagnostic checklist and exam presented in this article. To begin, the authors transferred diagnostic categories and examination tests to a currently published checklist and exam, which served as the initial model. [34] Having extensive experience creating and using the previously developed checklist and exam, the authors sought to update and create more practical documents to guide clinical evaluation. For the checklist, this included(1) updating diagnostic categories derived from the systematic review,

(2) reformatting the diagnostic checklist to be more user-friendly, and

(3) restructuring the exam to facilitate a more efficient clinical evaluation.Several versions of the checklist and exam were iteratively developed by the authors, who each have clinical practice and research experience. Checklist development priorities included improving ease of use by

(1) incorporating updated exam findings for potential use as a standalone exam document,

(2) restructuring the categories for a more logical flow,

(3) revising questions to add clarity (all yes answers indicated either a positive finding or evidence for a specific diagnosis), and

(4) organizing space to fit within a 2–page document.The clinical exam was likewise iteratively developed. The prior exam, which the authors also developed and used as a model, was modular, based on the diagnosis. Experience using the prior exam revealed that in many situations, evaluation occurred in a less structured manner. Often, the clinical exam was performed based more on patient position rather than diagnostic category. Therefore, because the checklist included examination tests for each diagnostic category, the authors created an exam form incorporating all procedures included within the checklist, though ordered by exam position. The purpose of creating both a checklist and exam form was to provide practitioners with more options to fit different clinical settings and practice preferences.

Results

Figure 1

Table 2

Table 3

Figure 2

Figure 3 The diagnostic checklist and exam include 3 general diagnostic categories:

(1) nociceptive pain,

(2) neuropathic pain, and

(3) sensitization.Each category is defined with a broadly accepted definition developed by the International Association for the Study of Pain.21 Figure 1 displays a visual model of diagnostic categories with specific diagnostic subtypes. Table 1 displays definitions of all diagnoses included in the systematic review and addressed in this article. Diagnostic criteria identified for office-based evaluation of LBP and the evidence basis from which they were obtained during the systematic review process are displayed in Tables 2 and 3.

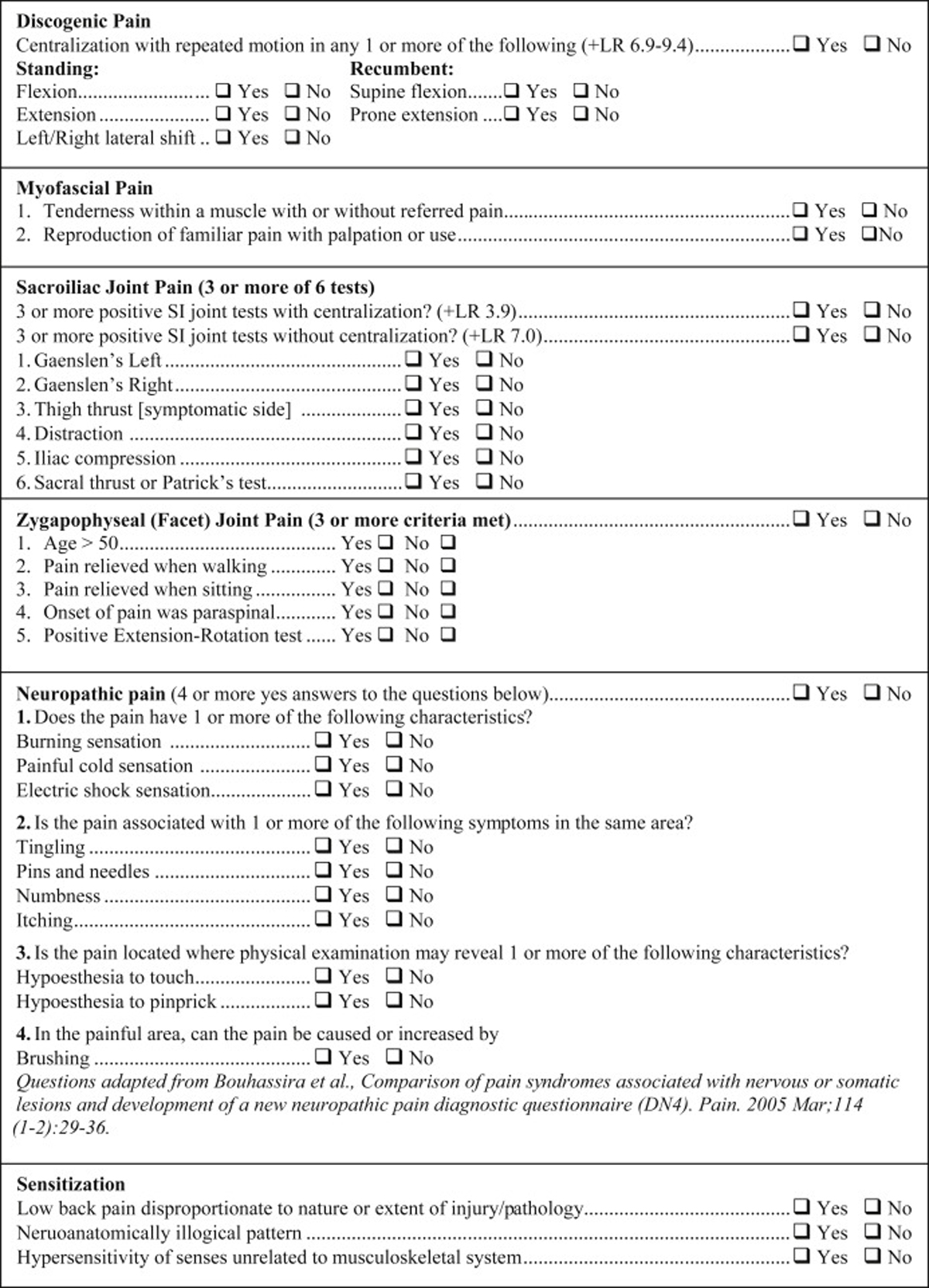

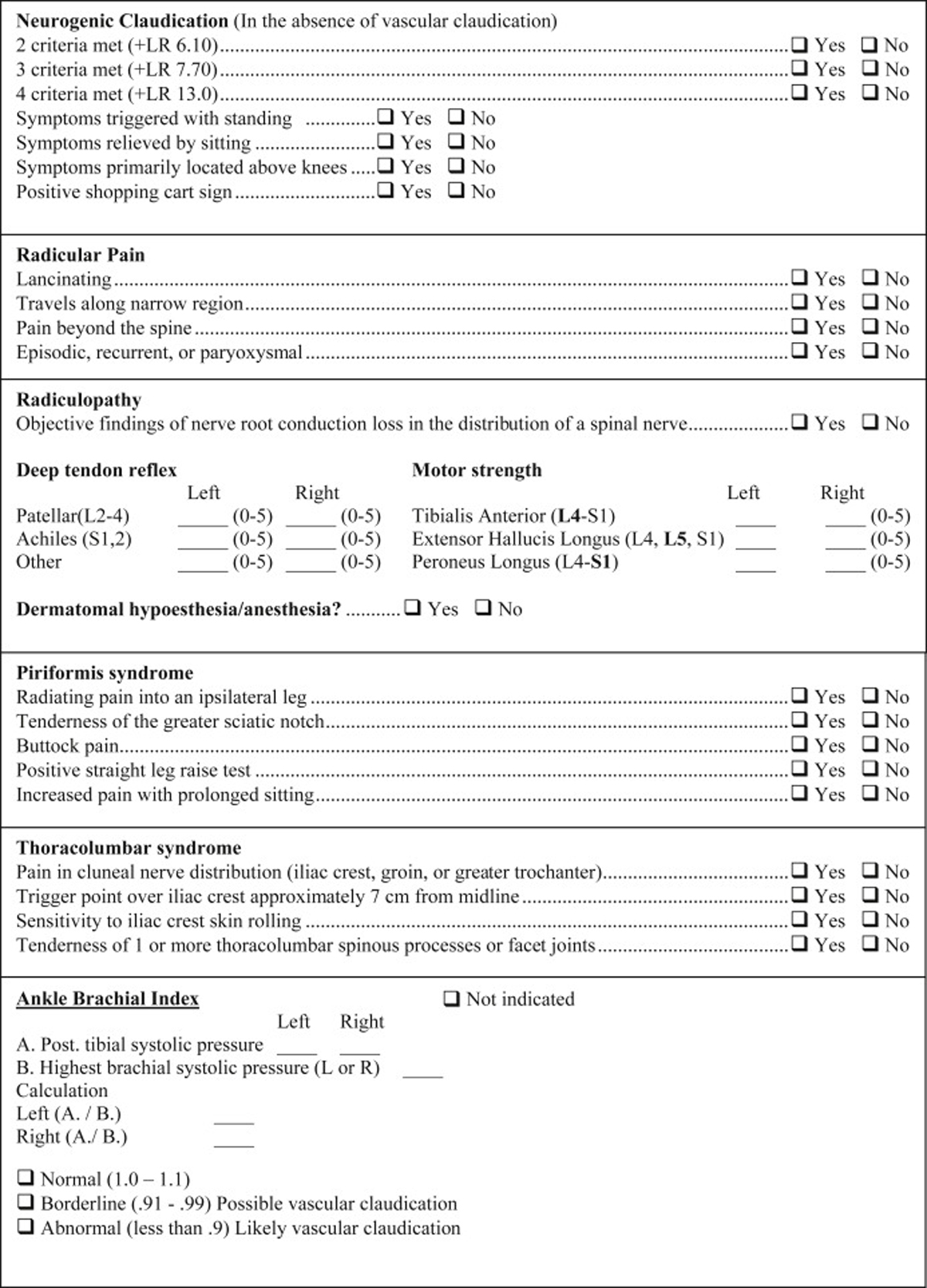

Diagnostic Checklist

Figures 2 and 3 combine to offer a practical diagnostic checklist designed to coordinate, summarize, document, and display evidence for or against a working diagnosis of neuromusculoskeletal LBP conditions. The checklist also serves as a reference document to ensure necessary information is obtained from a patient interview and exam. Evidence-based diagnostic criteria derived from the systematic review are listed as questions to be answered with a yes or no response. Most questions can be answered after obtaining a focused history. Thus, the checklist may be useful to help remind practitioners to obtain important clinical information, though it may not be exhaustive in some clinical situations.

The checklist is modular and designed to be reordered based on the needs of the clinical setting. The component modules can be printed and completed on paper or incorporated into an electronic health record. Some historical information may also be incorporated into patient questionnaires obtained prior to a face-to-face interview at the discretion of the user. Included within the checklist are evidence-based diagnostic criteria with applicable exam tests. These were included within the checklist for those who wish to also use it as an exam form. The checklist format facilitates its use as a clinical evaluation guide and documentation vehicle. When completed, the checklist efficiently displays where evidence for working diagnoses is and is not present.

We developed a sample exam that includes in-office tests needed to complete exam-related checklist items. Examination is ordered by major patient position (standing, seated, recumbent). However, the exam may be performed in any order deemed most appropriate by a practitioner. See the exam form online in Appendix A. We have provided an Instructional Video that gives an overview of this information (see video file online).

Discussion

Adoption of the biopsychosocial approach has lessened the focus on the search for symptom-producing tissues or processes causing LBP.9 However, the biopsychosocial model was not intended to eliminate biological understanding of disease. Instead, it recognizes that biologically based diagnosis can be insufficient in providing a full understanding of a patient and their need(s). [48, 49]

This article focuses on a pragmatic method of identifying in-office examination and historical evidence to support a working diagnosis based on a systematic review of the literature. Though including psychological, social, and environmental evaluation was outside the scope of the original systematic review and this article, evaluating these aspects are part of a comprehensive process designed to answer all 3 questions of diagnosis. [3, 4] Psychological, social, and environmental factors may be crucial to understanding and informing effective management approaches, which may require the expertise of mental health or other professionals.50

One complementary approach to diagnosis is a classification system for spine-related concerns developed by the Global Spine Care Initiative. [51] This system classifies spine-related conditions by symptom characteristics, functional deficits, and severity. The diagnostic process presented in this article provides criteria to help understand the strength of evidence for identifying likely pathophysiological processes underlying these classifications and potentially informing ongoing management decisions.

Evidence Supporting a Working Diagnosis

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, not all diagnostic criteria are supported by the same level of evidence, spawning the question: How much confidence can one place in a given diagnosis? Answering this question involves 4 factors:(1) the strength of scientific evidence supporting diagnostic criteria,

(2) whether other case characteristics influence the interpretation of clinical information,

(3) the prevalence of the condition when known, and

(4) whether other diagnoses can be largely ruled out.Stronger evidence for diagnostic criteria is typically supported by research including objective diagnostic tests that can confirm or rule out the presence of a condition. The diagnoses of discogenic pain, facet joint pain, and sacroiliac joint pain can be largely confirmed using provocation or anesthetic injections, which are the current objective standard. [35, 52–54] Combining prevalence data and performance statistics reported in studies using these tests can assist practitioners in understanding the amount of confidence that can/should be placed in these diagnoses.

For example, the centralization phenomenon has been shown to suggest discogenic pain.36 Using the prevalence of discogenic pain of 30% (range: 26%–42%), [54] the positive likelihood ratio of 6.9 as reported by Laslett et al results in approximately a 70% probability that discogenic pain is the dominant source of pain when centralization is present. [55] When other conditions are excluded, the probability increases further. Likelihood ratios range from 4.0 to 7.0 in most studies examining 3 or more positive sacroiliac joint tests. Combining this knowledge with the prevalence of sacroiliac joint pain (25%), reported by the majority of studies, [35] suggests that when 3 or more provocation tests reproduce familiar symptoms, the likelihood of sacroiliac pain is approximately 57% to 70%. A higher probability occurs when centralization is absent. [36]

Expert Consensus

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, several categories are supported by evidence from expert consensus agreement. In the absence of objective reference tests to independently confirm a diagnosis, expert consensus agreement of diagnostic criteria represents the highest level of available evidence. However, until such criteria can be rigorously tested using objective tests, accuracy will be largely unknown. Thus, future evidence is more likely to alter diagnostic criteria for conditions supported by evidence derived only from expert agreement. For such conditions, it is not possible to calculate a statistical probability of accuracy. In these cases, a lower confidence in these working diagnoses is reasonable until other conditions are largely excluded.

Conducting an ExamNociceptive and Neuropathic Pain Differentiating nociceptive and neuropathic pain or determining whether they are likely co-occurring can be a necessary part of clinical evaluation. [33] Included in Tables 2 and 3 are characteristics for neuropathic and nociceptive pain based on current expert consensus opinion. [12, 37] Based largely on these consensus-based criteria and International Association for the Study of Pain definitions, [21] several validated questionnaire instruments have been designed for in-office use to screen for neuropathic pain. These include the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS), S-LANSS (self-report version of LANSS), painDETECT questionnaire, McGill Pain Questionnaire, Standardized Evaluation of Pain tool, Douleur Neruopathique 4 (DN4), ID Pain questionnaire, and Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System Neuropathic Pain Quality Scale. [38–42, 56–59] There is some debate regarding the relative diagnostic accuracy of these instruments in different settings. We include questions from the DN4 in this exam based on ease of use, reliability, and availability. The DN4 has been independently assessed and consistently reported to be among the most discriminative instruments available. [60–63]

Some practitioners may wish to perform examination tests for a specific diagnosis before moving to another category. In such cases, the checklist can provide examination guidance. Appendix A displays all exam tests included in the checklist by patient position. However, both the exam and checklist are designed modularly, creating the potential for rearranging the order of items within either document to fit a variety of clinical settings or preferences.

In many situations, sections of the exam can be avoided. For example, examination for radicular pain, radiculopathy, and neurogenic claudication can be largely avoided when lower extremity symptoms are absent. When 3 sacroiliac joint tests reproduce familiar symptoms, additional testing is unnecessary to meet criteria for this category. Once centralization is observed while performing any single end-range loading, no further end-range maneuvers are needed to confirm this criterion for discogenic pain. Performing the extension-rotation test is only necessary when only 2 criteria for facet joint pain are obtained from the patient interview.

Low back pain with lower extremity radiation requires discerning among the greatest number of possible conditions. Virtually all working diagnoses discussed in this article can produce proximal and distal lower extremity symptoms through sclerotogenous referral or nerve insult. [15, 64] Symptoms may also represent a combination of conditions. For example, some evidence suggests that inflammation from the sacroiliac joint can extravasate (leak), causing combined sacroiliac joint and radicular pain. [65] Because lower extremity symptoms can also occur from vascular claudication, we included the ankle brachial index test (Appendix A), a noninvasive, in-office, and guideline-recommended procedure. [66] This simple test can help identify vascular claudication, a condition that can co-occur and be easily confused with neurogenic claudication. [20]Limitations and Future Studies

Negative implications arising from a process seeking to identify a specific working diagnosis occur when practitioners abandon psychosocial and environmental evaluation.67 Concentrating solely on biological causes for symptoms carries the potential for labeling patients with a condition that creates unnecessary morbidity and the potential to fail to recognize evidence for other, co-occurring, or underlying factors (anchoring) that may be critically important to management decisions. [19, 68]

It is not known how care should be ideally tailored for every condition addressed in this article to maximize clinical outcomes. Limitations in definitively confirming many conditions causing LBP prevent extensive research in this area. However, for some conditions, such as neurogenic claudication, research evidence suggesting clinical benefit for tailored interventions is emerging. [69] Several other studies also suggest individual characteristics or specific examination findings are associated with outcomes. [70–72]

The diagnostic checklist and exam presented in this article are based on a systematic review. Limitations of the systematic review include the possibility of missing articles and errant evidence interpretation. The strength of the scientific evidence supporting different working diagnoses for LBP varies, demanding clinical judgment that can appropriately render how much confidence can be placed in a working diagnosis and how that should influence management decisions. The limited nature of evidence for diagnostic criteria included in this article means that as new evidence becomes available, the contents of the checklist or the confidence practitioners can reasonably place in exam findings may change. The reliability of working diagnoses informed by evidence-based criteria will be influenced by the consistency of exam performance; by the accuracy and interpretation of exam findings; and by how well practitioners obtain, recognize, and synthesize clinically relevant information.

Lastly, the materials that we present in this study have been used by our clinical research team to streamline clinical evaluation and establish working diagnoses based on scientific evidence. However, we cannot say if they will help provide improved diagnoses or better care for patients. Future studies should evaluate these materials in different clinical settings to measure practical implementation and ease-of-use factors. Other research can focus on how diagnosis-related biases, such as confirmation and anchoring bias, are influenced by using these materials. Establishing a working diagnosis is part of a process designed to help inform management decisions. Additional materials should also be developed that will help support evidence-based decision-making in clinical practice. [73]

Conclusion

Based on a systematic review of the literature, this article describes an office-based examination leading to working diagnoses for common conditions causing or contributing to LBP. A practical diagnostic checklist for clinical evaluation at a primary spine care level may help to efficiently demonstrate evidence for or against working diagnoses.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Anna-Marie Schmidt, MM, DC, for reviewing manuscript drafts, providing critical feedback, and performing other activities relevant to this project.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

Drs Vining, Minkalis, Shannon, and Twist report grant support from the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary & Integrative Health 5UG3AT009761-02. Dr Shannon reports funding from the NCMIC Foundation. No funding agency was involved in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or manuscript writing. No other conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

References:

Definition of diagnosis by Merriam Webster. (Available at:)

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/diagnosisDefinition of diagnosis in English by Oxford Dictionaries.

Oxford Dictionaries | English. (Available at:)

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/diagnosis

Date accessed: February 1, 2019Murphy DR Hurwitz EL:

A Theoretical Model for the Development of a Diagnosis-based Clinical Decision Rule for

the Management of Patients with Spinal Pain

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007 (Aug 3); 8: 75Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL.

Application of a Diagnosis-Based Clinical Decision Guide in Patients with Low Back Pain

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2011 (Oct 22); 19: 26Lurie J.D.

What diagnostic tests are useful for low back pain?.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005; 19: 557-575Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, Hoy D, Karppinen J et al.

What Low Back Pain Is and Why We Need to Pay Attention

Lancet. 2018 (Jun 9); 391 (10137): 2356–2367

This is the second of 4 articles in the remarkable Lancet Series on Low Back Painvan Erp R.M.A. Huijnen I.P.J. Jakobs M.L.G. Kleijnen J. Smeets R.J.E.M.

Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain:

a systematic review.

Pain Pract. 2019; 19: 224-241Brisby H.

Pain origin and mechanisms in low back pain.

in: van de Kelft E. Surgery of the Spine and Spinal Cord: A Neurosurgical Approach.

Springer International Publishing, Cham2016: 399-406Deyo R.A. Dworkin S.F. Amtmann D. et al.

Report of the National Institutes of Health task force on research standards for chronic low back pain.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014; 37: 449-467Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr., Shekelle P, Owens DK:

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline

from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 478–491Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Nijs J., Apeldoorn A., Hallegraeff H., et al.

Low Back Pain: Guidelines for the Clinical Classification of

Predominant Neuropathic, Nociceptive, or

Central Sensitization Pain

Pain Physician. 2015 (May); 18 (3): E333–346Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, Decina P, Descarreaux M, Haskett D, Hincapie C, et al.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Other Conservative Treatments for Low Back Pain:

A Guideline From the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (May); 41 (4): 265–293Globe, G, Farabaugh, RJ, Hawk, C et al.

Clinical Practice Guideline:

Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 1–22Laplante B.L. Ketchum J.M. Saullo T.R. DePalma M.J.

Multivariable analysis of the relationship between pain referral patterns and the source

of chronic low back pain.

Pain Physician. 2012; 15: 171-178Hopayian K. Danielyan A.

Four symptoms define the piriformis syndrome: an updated systematic review of its clinical features.

Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018; 28: 155-164Oikawa Y. Ohtori S. Koshi T. et al.

Lumbar disc degeneration induces persistent groin pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012; 37: 114-118O’Neill C.W. Kurgansky M.E. Derby R. Ryan D.P.

Disc stimulation and patterns of referred pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002; 27: 2776-2781Taylor A.J. Kerry R.

When chronic Pain is not “chronic pain”: lessons from 3 decades of pain.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017; 47: 515-517Gerhard-Herman M.D. Gornik H.L. Barrett C. et al.

2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease:

a report of the American College of Cardiology/

American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69: e71-e126International Association for the Study of Pain IASP terminology. (Available at:)

https://www.iasp-pain.org/terminology?navItemNumber=576

Date accessed: February 1, 2019Katz J.N. Harris M.B.

Lumbar spinal stenosis.

N Engl J Med. 2008; 358: 818-825Haswell K. Gilmour J.M. Moore B.J.

Lumbo-sacral radiculopathy referral decision-making and primary care management. A case report.

Man Ther. 2015; 20: 353-357Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, et al.

Noninvasive Treatments for Low Back Pain

Comparative Effectiveness Review no. 169

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; (February 2016)Bardin L.D. King P. Maher C.G.

Diagnostic triage for low back pain: a practical approach for primary care.

Med J Aust. 2017; 206: 268-273Stochkendahl MJ, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J et al.

National Clinical Guidelines for Non-surgical Treatment of Patients with

Recent Onset Low Back Pain or Lumbar Radiculopathy

European Spine Journal 2018 (Jan); 27 (1): 60–75Ball J.R. Balogh E.

Improving diagnosis in health care: highlights of a report from the National Academies

of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Ann Intern Med. 2016; 164: 59-61Kress V.E. Hoffman R.M. Eriksen K.

Ethical dimensions of diagnosing: considerations for clinical mental health counselors.

Couns Values. 2010; 55: 101-112Wong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, et al.

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Noninvasive Management of Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury

Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

European J Pain 2017 (Feb); 21 (2): 201–216Snelgrove S. Liossi C.

Living with chronic low back pain: a metasynthesis of qualitative research.

Chronic Illn. 2013; 9: 283-301Traeger A.C. Hübscher M. Henschke N. Moseley G.L. Lee H. McAuley J.H.

Effect of primary care-based education on reassurance in patients with acute low back pain:

systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175: 733-743Louw A. Zimney K. Puentedura E.J. Diener I.

The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain:

a systematic review of the literature.

Physiother Theory Pract. 2016; 32: 332-335Vining R, Shannon Z, Minkalis A, Twist E.

Current Evidence for Diagnosis of Common Conditions Causing Low Back Pain:

Systematic Review and Standardized Terminology Recommendations

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 651–664Vining R, Potocki E, Seidman M, Morgenthal AP.

An Evidence-based Diagnostic Classification System For Low Back Pain

J Canadian Chiropractic Assoc 2013 (Sep); 57 (3): 189–204Simopoulos T. Manchikanti L. Singh V. et al.

A systematic evaluation of prevalence and diagnostic accuracy of sacroiliac joint interventions.

Pain Physician. 2012; 15: E305-E344Petersen T, Laslett M, Juhl C.

Clinical Classification in Low Back Pain: Best-evidence Diagnostic Rules Based on Systematic Reviews

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017 (May 12); 18 (1): 188Smart K.M. Blake C. Staines A. Thacker M. Doody C.

Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: part 3 of 3:

symptoms and signs of nociceptive pain in patients with low back (±leg) pain.

Man Ther. 2012; 17: 352-357Bennett M.I. Attal N. Backonja M.M. et al.

Using screening tools to identify neuropathic pain.

Pain. 2007; 127: 199-203Bennett M.I. Smith B.H. Torrance N. Lee A.J.

Can pain can be more or less neuropathic? Comparison of symptom assessment tools

with ratings of certainty by clinicians.

Pain. 2006; 122: 289-294Mayoral V. Pérez-Hernández C. Muro I. Leal A. Villoria J. Esquivias A.

Diagnostic accuracy of an identification tool for localized neuropathic pain based on the IASP criteria.

Curr Med Res Opin. 2018; 34: 1465-1473Askew R.L. Cook K.F. Keefe F.J. et al.

A PROMIS measure of neuropathic pain quality.

Value Health. 2016; 19: 623-630Dworkin R.H. Turk D.C. Trudeau J.J. et al.

Validation of the short-form McGill pain questionnaire-2 (SF-MPQ-2) in acute low back pain.

J Pain. 2015; 16: 357-366Laslett M. McDonald B. Aprill C.N. Tropp H. Oberg B.

Clinical predictors of screening lumbar zygapophyseal joint blocks:

development of clinical prediction rules.

Spine J. 2006; 6: 370-379International Association for the Study of Pain

Spinal pain, section 1: spinal and radicular pain syndromes.

https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673&navItemNumber=677Nadeau M. Rosas-Arellano M.P. Gurr K.R. et al.

The reliability of differentiating neurogenic claudication from vascular claudication

based on symptomatic presentation.

Can J Surg. 2013; 56: 372-377Maigne J.Y. Doursounian L.

Entrapment neuropathy of the medial superior cluneal nerve.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997; 22: 1156-1159Alptekin K. Örnek N.I. Ayd?n T. et al.

Effectiveness of exercise and Local steroid injections for the thoracolumbar junction

syndrome (the Maigne’s syndrome) treatment.

Open Orthop J. 2017; 11: 467-477Alonso Y.

The biopsychosocial model in medical research:

the evolution of the health concept over the last two decades.

Patient Educ Couns. 2004; 53: 239-244Adler R.H.

Engel’s biopsychosocial model is still relevant today.

J Psychosom Res. 2009; 67: 607-611Tousignant-Laflamme Y. Martel M.O. Joshi A.B. Cook C.E.

Rehabilitation management of low back pain – it’s time to pull it all together!.

J Pain Res. 2017; 10: 2373-2385Haldeman S., Johnson C.D., Chou R. et al.

The Global Spine Care Initiative: Classification System for Spine-related Concerns

European Spine Journal 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 889–900Rupert M.P. Lee M. Manchikanti L. Datta S. Cohen S.P.

Evaluation of sacroiliac joint interventions: a systematic appraisal of the literature.

Pain Physician. 2009; 12: 399-418Boswell M.V. Manchikanti L. Kaye A.D. et al.

A best-evidence systematic appraisal of the diagnostic accuracy and utility of facet

(zygapophysial) joint injections in chronic spinal pain.

Pain Physician. 2015; 18: E497-E533Manchikanti L. Benyamin R.M. Singh V. et al.

An update of the systematic appraisal of the accuracy and utility of lumbar discography in chronic low back pain.

Pain Physician. 2013; 16: SE55-SE95Laslett M. Öberg B. Aprill C.N. McDonald B.

Centralization as a predictor of provocation discography results in chronic low back pain,

and the influence of disability and distress on diagnostic power.

Spine J. 2005; 5: 370-380Attal N. Perrot S. Fermanian J. Bouhassira D.

The neuropathic components of chronic low back pain:

a prospective multicenter study using the DN4 questionnaire.

J Pain. 2011; 12: 1080-1087Scholz J. Mannion R.J. Hord D.E. et al.

A novel tool for the assessment of pain: validation in low back pain.

PLoS Med. 2009; 6e1000047Bouhassira D. Attal N. Alchaar H. et al.

Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of

a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4).

Pain. 2005; 114: 29-36Bennett M.

The LANSS Pain Scale: the Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs.

Pain. 2001; 92: 147-157Jones 3rd, R.C. Backonja M.M.

Review of neuropathic pain screening and assessment tools.

Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013; 17: 363VanDenKerkhof E.G. Stitt L. Clark A.J. et al.

Sensitivity of the DN4 in screening for neuropathic pain syndromes.

Clin J Pain. 2018; 34: 30-36Mathieson S. Maher C.G. Terwee C.B. Folly de Campos T. Lin C.W.

Neuropathic pain screening questionnaires have limited measurement properties. A systematic review.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2015; 68: 957-966Diagnostic Methods for Neuropathic Pain: A Review of Diagnostic Accuracy.

Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2015. (Available at:)

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304863/

Date accessed: February 1, 2019van der Wurff P. Buijs E.J. Groen G.J.

Intensity mapping of pain referral areas in sacroiliac joint pain patients.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006; 29: 190-195Fortin J.D. Vilensky J.A. Merkel G.J.

Can the sacroiliac joint cause sciatica?.

Pain Physician. 2003; 6: 269-271Ahmed O. Hanley M. Bennett S. et al.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria vascular claudication—assessment for revascularization.

J Am Coll Radiol. 2017; 14: S372-S379Setchell J. Costa N. Ferreira M. Makovey J. Nielsen M. Hodges P.W.

Individuals’ explanations for their persistent or recurrent low back pain: a cross-sectional survey.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017; 18: 466Rylander M. Guerrasio J.

Heuristic errors in clinical reasoning.

Clin Teach. 2016; 13: 287-290Ammendolia C. Côté P. Southerst D. et al.

Comprehensive nonsurgical treatment versus self-directed care to improve walking ability in

lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized trial.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018; 99: 2408-2419.e2Arnold Y. L. Wong, Eric C. Parent, Sukhvinder S. Dhillon, Narasimha Prasad, Dino Samartzis, Gregory N. Kawchuk

Differential Patient Responses to Spinal Manipulative Therapy

and their Relation to Spinal Degeneration and

Post-treatment Changes in Disc Diffusion

European Spine Journal 2019 (Feb); 28 (2): 259–269Ford J.J. Richards M.C. Surkitt L.D. et al.

Development of a multivariate prognostic model for pain and activity limitation in people

with low back disorders receiving physiotherapy.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018; 99: 2504-2512.e12Hartvigsen L, Kongsted A, Hestbaek L.

Clinical Examination Findings as Prognostic Factors in Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review of the Literature

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2015 (Mar 23); 23: 13Vining RD, Shannon ZK, Salsbury SA, Corber L, Minkalis AL, Goertz CM.

Development of a Clinical Decision Aid for Chiropractic Management

of Common Conditions Causing Low Back Pain in Veterans:

Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 677–693

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to LOW BACK GUIDELINES

Return to CLINICAL PREDICTION RULE

Since 5-17-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |