Directional Preference and Functional Outcomes

Among Subjects Classified at High Psychosocial Risk Using STarTThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Physiother Res Int. 2018 (Jul); 23 (3): e1711 ~ FULL TEXT

Mark W. Werneke, Susan Edmond, Michelle Young, David Grigsby, Brian McClenahan, Troy McGill

Doctoral Programs in Physical Therapy,

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey,

Newark, NJ, USA

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Physiotherapy has an important role in managing patients with non-specific low back pain who experience elevated psychosocial distress or risk for chronic disability. In terms of evidence-based physiotherapy practice, cognitive-behavioural approaches for patients at high psychosocial risk are the recommended management to improve patient treatment outcomes. Evidence also suggests that directional preference (DP) is an important treatment effect modifier for prescribing specific exercises for patients to improve outcomes. Little is known about the influence of treatment techniques based on DP on outcomes for patients classified as high psychosocial risk using the Subgroups for Targeted Treatment (STarT Back Screening Tool). This study aimed to examine the association between functional status (FS) at rehabilitation discharge for patients experiencing low back pain classified at high STarT psychosocial risk and whose symptoms showed a DP versus No-DP.

METHODS: High STarT risk patients (n = 138) completed intake surveys, that is, the lumbar FS of Focus On Therapeutic Outcomes, Inc., and STarT, and were evaluated for DP by physiotherapists credentialed in McKenzie methods. The FS measure of Focus On Therapeutic Outcomes, Inc., was repeated at discharge. DP and No-DP prevalence rates were calculated. Associations between first-visit DP and No-DP and change in FS were assessed using univariate and multivariate regression models controlling for 11 risk-adjusted variables.

RESULTS: One hundred nine patients classified as high STarT risk had complete intake and discharge FS and DP data. Prevalence rate for DP was 65.1%. A significant and clinically important difference (7.98 FS points; p = .03) in change in function at discharge between DP and No-DP was observed after controlling for all confounding variables in the final model.

CONCLUSION: Findings suggest that interventions matched to directional preference (DP) are effective for managing high psychological risk patients and may provide physiotherapists with an alternative treatment pathway compared to managing similar patients with cognitive-behavioural approaches. Stricter research designs are required to validate study conclusions.

KEYWORDS: STarT; directional preference; low back pain; outcome measurement

From the FULL TEXT Article:

INTRODUCTION

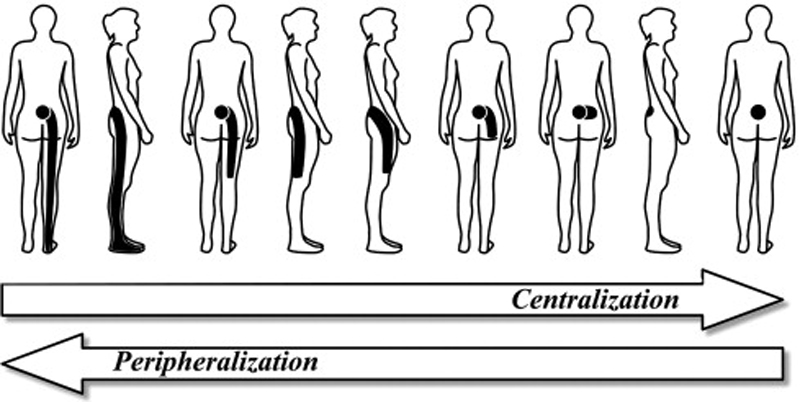

Directional preference (DP) is an important examination finding identified within many treatment-based physiotherapy classification systems in the United States and internationally (Delitto, Erhard, & Bowling, 1995; McKenzie & May, 2004; Petersen et al., 2003). DP is identified if the patient's most distal pain intensity decreased, abolished, or centralized, and/or their lumbar range of motion improved in response to repeated end range movement tests or positional loading strategies following McKenzie methods (McKenzie & May, 2004). The prevalence rates reported for DP observed during initial evaluation ranged between 60% and 78% (May & Aina, 2012). Clinical interest by physiotherapists for identifying DP during the initial evaluation of patients with non-specific low back pain (NSLBP) is supported by recent data published in several reviews (Long, Donelson, & Fung, 2004; Long, May, & Fung, 2008; Werneke et al., 2011).

Evidence also suggests that when DP is used as a treatment effect modifier to inform treatment of patients with NSLBP, clinical outcomes are improved (May & Aina, 2012). Specifically, clinical trials have demonstrated significantly better treatment outcomes when patients are randomized to the appropriate DP exercises compared to other types of exercises or interventions (Brennan et al., 2006; Browder, Childs, Cleland, & Fritz, 2007; Long et al., 2004). For example, Long et al. (2004) randomized patients into treatment groups either matching or unmatching exercises according to the patient's DP. The results demonstrated greater reductions in disability over a 2-week follow-up period when the specific exercise regimen was matched to the patient's DP compared to the group receiving unmatched exercise prescriptions. Long et al. (2008) also reported that patients with a DP who received matched exercise treatment according to the patient's DP had a 7.8 times greater likelihood of a good outcome compared with those who did not receive matched exercises (Long et al., 2008).

The spine literature recognizes that patients with NSLBP are biopsychosocially complex because of known interacting effects between sociodemographic, psychosocial, and biomechanical or physical factors experienced by each individual patient (O'Sullivan, Caneiro, O'Keeffe, & O'Sullivan, 2016). Psychosocial screening is considered a high priority for clinicians to identify patients for elevated pain-related psychosocial distress because such distress is a known precursor for increased risk of chronic disability and/or delayed treatment recovery (George & Beneciuk, 2015). To assist clinicians to accurately identify patients by psychosocial risk, Hill et al. (2008) developed a nine-item multidimensional biopsychosocial screening measure, that is, Subgroups for Targeted Treatment (STarT) Back Screening Tool. A primary purpose for STarT screening was to target treatment strategies for each of the three STarT risk patient subgroups, that is, low, medium, or high.

For patients with NSLBP who are classified at high psychosocial risk during the initial evaluation, contemporary clinical practice guidelines (Airaksinen et al., 2006) recommend managing these patients according to the biopsychosocial model, which endorses interdisciplinary treatments combining medical, physiotherapy, and mental health care services to improve patient outcomes and decrease health care costs (Hill et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2014). For those patients classified at high-risk using the STarT tool, the recommended treatment is formal cognitive-behavioural approaches (CBA) augmented by evidencebased physiotherapy intervention. To equip front-line clinicians with the necessary CBA intervention skills to effectively manage these high-risk patients, physicians and physiotherapists were recommended to attend advanced CBA educational and training programs (Sowden et al., 2012). Foster et al. (2014) reported large clinically important differences in 6-month patient self-report disability outcomes for high STarT risk patients prescribed with CBA-targeted treatments following STarT stratified management approach compared to similar patients receiving usual care in family practice.

There is scant guidance for physiotherapists treating patients with NSLBP when both favourable (i.e., DP) and unfavourable (i.e., high STarT risk) prognostic indicators are identified during the initial examination. The purpose of this study was therefore to examine the association between changes in functional status (FS) outcomes at discharge from rehabilitation among high STarT risk patients experiencing low back pain with a DP versus No-DP at baseline. We hypothesize that patients classified at high STarT risk whose symptoms show a first-visit DP and whose treatment was matched to their DP will achieve better FS outcomes at discharge from physiotherapy services compared to those high STarT risk patients whose symptoms do not demonstrate DP. Because prior evidence suggests that patients demonstrating DP can be rapidly and successfully treated with the performance of matching directional exercises (Long et al., 2004; Long et al., 2008), we believe that high STarT risk patients with DP are actually low-risk patients despite their baseline STarT Back score. If results from this study are promising, further research using stricter designs would be required to examine if targeted treatment using DP-matched exercises versus the STarT stratification treatment approach produces better outcomes.

METHODS

Study design

Data were collected between January 2013 and May 2017. All participating clinicians collected patient data and outcomes using an international medical rehabilitation data management company, that is, Focus On Therapeutic Outcomes, Inc. (FOTO), Knoxville, TN, USA (Swinkels et al., 2007). The Rutgers University Institutional Review Board approved the project. The study did not include changes in clinical practice, data documentation, or treatment; therefore, patient informed consent was not required.

Subjects

One hundred thirty-eight patients older than 17 years of age experiencing NSLBP complaints, classified into a high STarT risk category at baseline, and referred to a participating outpatient physiotherapy clinic were included. Patients were excluded due to pregnancy or suspicion of serious spinal pathology such as fracture, cancer, or visceral diseases.

Clinicians

Eight physiotherapists, credentialed in McKenzie methods (McKenzie & May, 2004), participated in data collection. Four clinicians achieved the highest level of McKenzie training and were credentialed by the International McKenzie Institute as Diplomats; and four clinicians were certified for achieving basic competency in McKenzie methods. Practice settings were diverse across private practice, hospital-based, and military outpatient physiotherapy clinics. Although participating physiotherapists were not blinded to STarT risk classification, no physiotherapist in this study received formal CBA training as recommended by the STarT management approach (Hill et al., 2008; Sowden et al., 2012).

Procedures

Patients completed the STarT and FOTO's FS Lumbar Computer AdaptiveTest (LCAT) measures at intake (Hart, Werneke, Wang, Stratford, & Mioduski, 2010; Hill et al., 2008). The LCAT is a psychometrically strong outcome measure to assess the patient's FS and change in FS (Hart et al., 2010; Hart, Mioduski, Werneke, & Stratford, 2006). The LCAT FS measure was repeated at discharge. In addition, the following intake patient and physiotherapist characteristics were included in the model, because they are shown to influence FS outcomes: age, gender, symptom duration, payer, use of medication at intake, exercise history, lumbar surgical history, prior treatment, condition complexity determined 29 possible comorbid conditions, McKenzie credentialing level, and treatment duration (Table 1).

Classification approaches

STarT Back Screening Tool stratification and scoring techniques have been described in detail elsewhere (Hill et al., 2008). Research findings have supported good reliability, validity, clinical utility, and usefulness for screening patients with lumbar impairments using STarT Back Screening Tool (Hill et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2014; Von Korff et al., 2014; Wideman et al., 2012).

DP classification

The operational definition for examining DP used in our study has been previously described and recommended (Long et al., 2008; Werneke et al., 2011). DP was identified if the patient's most distal pain intensity decreased, abolished, or centralized, and/or their lumbar range of motion improved in response to repeated end range movement tests or positional loading strategies. Interrater chance corrected agreement (Kappa) for identifying a DP for patients' whose symptoms centralized has been reported to be excellent (Kappa = .90; Kilpikoski et al., 2002).

Treatment

Treatment processes were guided by DP, if present. For example, if lumbar extension was identified as the patient's DP, exercises that moved the patient towards lumbar extension and manual procedures that produced lumbar extension forces were applied. If patients were classified into a No-DP category, an individualized active rehabilitation plan was determined at the discretion of the treating therapist. All patients regardless of DP received the same educational approach: Empower the patient to become actively involved in his or her own recovery to reduce fear of physical activity and movement intolerance. There was no attempt to standardize care beyond these guidelines.

Outcome

FOTO's LCAT FS measure used in the study has been previously described in detail (Hart et al., 2006; Hart et al., 2010). Briefly, FS scores estimated by the LCAT FS measure ranged from 0 (low) to 100 (high functioning) on a linear metric. The items in the LCAT FS measure item bank have demonstrated internal consistency, reliability, validity, sensitivity, and responsiveness (minimal clinically important difference averaged 5 points).

Data analyses

The percentage (%) of patients classified as first-visit DP or No-DP was calculated. Patient and therapist characteristics are reported inTable 1. Univariate and multivariate regression models examined the association between DP and No-DP patient subgroups and change in FS at discharge from rehabilitation services.

Our multivariate model evaluated for confounding by the following 11 risk-adjusted variables:age,

gender,

acuity,

payer,

medication use at intake,

surgical history,

exercise history,

prior treatment episodes,

medical comorbidities,

treatment duration, and

post graduate McKenzie education and training.Confounding effects were determined using the criteria that a 10% change in the effect measure when adding the potential confounder(s) to the baseline model represents meaningful confounding (SAS Institute Inc., 1999). We calculated beta coefficients for DP versus No-DP subgroups in which the reference standard was DP. Variables entering the model were checked for collinearity by evaluating the condition index.

We examined the potential for bias due to loss to follow-up by comparing patient and therapist characteristics for those patients with complete FS and DP data at intake versus those with missing FS data at discharge (Table 2).

RESULTS

One-hundred and nine subjects classified as high STarT risk at baseline had DP intake and discharge FS data. Of these, 65.1% were classified as having DP versus 34.9% having No-DP. Twenty-nine patients were lost to follow up. The completion rate (i.e., complete intake and discharge outcome data) was 79%. There were no differences between drop-outs and those who completed treatment in 7 of the 11 model variables (Table 2) including intake FS, which was the strongest variable in the model. However patients who dropped-out were more likely to have No-DP, chronic symptoms, use of pain medications, and longer treatment duration.

Overall, subjects' FS improved from 42.2 to 69.6 FS points, for a total increase of 27.4 units. Scores among subjects who demonstrated a DP at intake increased from 43.6 to 74.4, a change of 30.8 points over an average of 7.5 visits, whereas those who did not demonstrate a DP at intake increased from 39.5 to 60.6, a change of 21.0 points while using an average of 8.0 visits. These findings represent a significant association in change in FS favouring high STarT risk patients who demonstrated a DP (p = .0009, beta coefficient [–]10.82) versus No- DP.

We evaluated for potential confounding by the aforementioned 11 risk-adjustment variables.

The following seven variables demonstrated meaningful confounding effects:age,

duration of symptoms,

payer,

exercise history,

prior treatment episode,

condition complexity, and

post graduate McKenzie education.The condition index for this analysis was 45.9. Analyses with condition indexes above 30 are considered to be significantly affected by colinearity (SAS Institute Inc., 1999). Subsequent analyses showed that age and condition complexity demonstrated colinearity effects in this association and was therefore deleted from the multivariate model. With age and condition complexity deleted from the model, the condition index decreased to 29.5. This model was rechecked for meaningful confounding, and all remaining variables were retained.

The final model therefore includedintake FS score,

duration of symptoms,

payer,

exercise history,

prior treatment episode, and

post graduate McKenzie education.In the final model, there was a significant and clinically important difference, that is, (–)7.98 (p = .03), in change in FS at discharge between DP and No-DP.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the association between changes in FS at discharge from rehabilitation for high STarT risk patients experiencing low back pain whose symptoms showed a DP versus No-DP at baseline. First-visit DP was both significant and clinically important for explaining FS outcomes at discharge. We had anticipated that DP data may be predictive of good FS outcomes, in part because the treatment prescribed by the participating therapists in our study was matched to the patient's DP. Evidence suggests that DP is associated with favourable treatment outcomes when patients were randomized to the appropriate DP-matched exercises (Brennan et al., 2006; Browder et al., 2007; Long et al., 2004).

There are scant data examining DP as a baseline prognostic variable for predicting FS outcomes (Delitto et al., 2012; May & Aina, 2012). In the only study that we are aware of which examined DP's prognostic value, the authors reported that first-visit DP was predictive of pain intensity but not FS at discharge for patients with low back pain referred to physiotherapy services (Werneke et al., 2011). In contrast with this earlier study, our results indicated that DP was associated with improved FS outcomes. Differences in sample sizes, patient characteristics including high STarT risk, and number of independent variables controlled for in the models could partially explain contrasting FS outcome results between our current study and previous findings (Werneke et al., 2011).

Our inclusion criteria for this study were restricted to patients with NSLBP who were classified at high STarT psychosocial risk. Prior research has shown that these patients have a particularly poor treatment prognosis if not managed by comprehensive multifactorial interventions as demonstrated by the STarT approach combining a formal CBA with evidence-based physiotherapy interventions (Hill et al., 2008). The STarT stratification approach applying prognostic screening to matched treatment pathways is recommended for improved shortand long-term health benefits, improved function, and cost savings compared to usual care (Hill et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2014).

Despite recommendations for targeting patients classified at high STarT risk for formal CBA interventions, the majority of high STarT risk patients in our study not only demonstrated DP during the initial evaluation but also responded well with significant and clinically important increases in FS scores at discharge compared to the No-DP subgroup. Patients at high risk who demonstrated DP were not managed by STarT stratification treatments but were prescribed specific exercises matched to DP based on McKenzie methods. Our data suggest that physiotherapists credentialed in McKenzie methods can consider DP-matched exercises as a potential alternative method to STarT stratification treatments to improve functional outcomes when managing high STarT risk patients with NSLBP.

The foundation of the McKenzie method is built on patient education consisting of empowerment, reassurance, and active self-management encouraging patients to adhere to their intervention plan during therapy sessions and at home between treatment sessions (May, 2007). Many of these patient self-care principles are similar to the patient educational strategies emphasized and reinforced within formal cognitive behavioural training programs (Main, Sowden, Hill, Watson, & Hay, 2012; Sowden et al., 2012). Evidence suggests positive effects of the McKenzie system for decreasing individual psychosocial risk factors, such as elevated distress or elevated fear avoidance beliefs, while simultaneously improving patients' functional outcomes (Al-Obaidi, Al-Sayegh, Ben Nakhi, & Skaria, 2013, Werneke et al., 2009, 2011).

It is therefore possible that our results could have been associated with these McKenzie biopsychosocial patient educational principles utilized by clinicians trained in the McKenzie approach independent of DP or No-DP. However, the same McKenzie patient educational approach was utilized regardless of DP classification category. Although both groups, that is, DP and No-DP, improved FS during the episode of care, if the educational approach was solely responsible for the observed association between DP and FS outcomes, we would have expected no significant difference between DP and No-DP subgroup outcomes. It is therefore plausible that the presence of a DP enhances the effects of McKenzie patient education strategies. Nevertheless, we had no hypotheses regarding how high STarT risk stratification would interact with specific physical therapy interventions, because causality between interventions and outcome was not possible based on the study design.

Participating physiotherapists in our study as well as others (Beneciuk et al., 2013; Beneciuk, Fritz, & George, 2014; Fritz, Beneciuk, & George, 2011) did not receive formal CBA training and did not follow recommended STarT-targeted treatment pathways. Despite physiotherapists' lack of formal CBA education and training, significant improvements in FS scores at discharge from physiotherapy for high-risk STarT patients with NSLBP have been consistently reported (Beneciuk et al., 2013, 2014; Fritz et al., 2011). Participating therapists in these other studies were trained in a popular physiotherapy treatment-based classification approach that included DP in its algorithm (Delitto et al., 1993). So, despite initial favourable results supporting the importance of formal CBA training to improve patient outcomes and reduce health care costs (Hill et al., 2011, Foster et al., 2014, von Korff et al., 2014, Wideman et al., 2012), preliminary evidence from our study suggests that DP may be an effective alternative approach for managing patients with elevated pain-related psychosocial distress and that formal CBA training may not be required to achieve successful patient outcomes.

Limitations

Not all patients classified at high STarT risk in our study (21%) completed physical therapy care; therefore, our results need to be interpreted in light of missing data. However, our completion rate was only slightly lower compared to other studies examining physiotherapy outcomes related to STarT stratification. For example, drop-out rates of approximately 18% and 16% were reported respectively by Fritz et al. (2011) and Beneciuk et al. (2014). However, these two studies reported drop-out rates for the entire sample regardless of baseline STarT risk levels, whereas our drop out results pertained specifically for patients with higher biopsychosocial complexity who were classified into the high STarT risk category.

Our study design was a case series examining a sample of convenience, which limits the generalizability of our results. In addition, we cannot infer a cause and effect between any treatments and outcomes observed in our study nor suggest that treatments based on DP are more effective compared to STarT-recommended treatments for patients classified at elevated psychosocial risk. Stronger research designs are required to validate our study's findings.

Regardless of best efforts to adjust for differences in our patient case mix, we acknowledge that a limitation of observational research is that we can only control for potential confounders that we measured. There may be unmeasured variables over which we have no control or simply did not collect data on that might have influenced our study results, for instance, a delay in treatment time, administration policy regarding the number of patients treated by the therapist per hour, or other patient socio-economic status and financial resources to attend physiotherapy services.

CONCLUSION

Study results suggest that patients who are at high STarT risk and demonstrate DP during the first visit report greater improvements in function than those high STarT risk patients who do not demonstrate firstvisit DP. These findings suggest that DP may provide an alternative treatment pathway compared to targeted interventions recommended by STarT proponents (Hill et al., 2008; Foster et al., 2014, Sowden et al., 2012). Nevertheless, future research using stricter designs is warranted to validate our results.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed to either the data collection, writing and preparing the manuscript, or statistical analyses of the data. All authors have given final approval for the manuscript submitted to Physiotherapy Research International.

References:

Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al.

COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain Chapter 4.

European Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain

European Spine Journal 2006 (Mar); 15 Suppl 2: S192–300Al-Obaidi, S. M., Al-Sayegh, N. A., Ben Nakhi, H., & Skaria, N. (2013).

Effectiveness of McKenzie intervention in chronic low back pain:

A comparison based on the centralization phenomenon utilizing selected

bio-behavioral and physical measures.

International Journal of Physical Medicine Rehabilitation, 1, 4.Beneciuk, J. M., Bishop, M. D., Fritz, J. M., Robinson, M. E., Asal, N. R. (2013).

The STarT Back Screening Tool and individual psychological measures:

Evaluation of prognostic capabilities for low back pain clinical outcomes

in outpatient physical therapy settings.

Physical Therapy, 93, 321–333.Beneciuk, J. M., Fritz, J. M., & George, S. Z. (2014).

The STarT Back Screening Tool for prediction of 6-month clinical outcomes:

Relevance of change patterns in outpatient physical therapy settings.

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 44, 656–664.Brennan, G. P., Fritz, J. M., Hunter, S. J., Thackeray, A., Delitto, A. (2006).

Identifying subgroups of patients with acute/subacute “nonspecific” low back pain:

Results of a randomized clinical trial.

Spine, 31, 623–631.Browder, D. A., Childs, J. D., Cleland, J. A., & Fritz, J. M. (2007).

Effectiveness of an extension-oriented treatment approach in a subgroup of subjects

with low back pain: A randomized clinical trial.

Physical Therapy, 87, 1608–1618.Delitto, A., Erhard, R. E., & Bowling, R. W. (1995).

A treatment-based classification approach to low back syndrome:

Identifying and staging patients for conservative treatment.

Physical Therapy, 75, 470–485.Delitto, A., George, S.Z., Van Dillen, L.R., Whitman, J.M., Sowa, G., Shekelle, P. (2012).

Low Back Pain: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification

of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the

American Physical Therapy Association

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 42, A1–A57.Foster, N. E., Mullis, R., Hill, J. C., Lewis, M., Whitehurst, D., Doyle, C. (2014).

Effect of stratified care for low back pain in family practice (IMPaCT back):

A prospective population-based sequential comparison.

Annals of Family Medicine, 12, 102–111.Fritz, J. M., Beneciuk, J. M., & George, S. Z. (2011).

Relationship between categorization with the STarT Back Screening Tool and prognosis

for people receiving physical therapy for low back pain.

Physical Therapy, 91, 722–732.George, S. Z., & Beneciuk, J. M. (2015).

Psychological predictors of recovery from low back pain: A prospective study.

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 16, 49Hart, D. L., Mioduski, J. E., Werneke, M. W., & Stratford, P. W. (2006).

Simulated computerized adaptive test for patients with lumbar spine impairments

was efficient and produced valid measures of function.

Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 59, 947–956.Hart, D. L., Werneke, M. W., Wang, Y. C., Stratford, P. W., & Mioduski, J. E. (2010).

Computerized adaptive test for patients with lumbar spine impairments produced valid

and responsive measures of function.

Spine, 35, 2157–2164.Hill JC, Dunn KM, Lewis M, et al.

A Primary Care Back Pain Screening Tool:

Identifying Patient Subgroups For Initial Treatment

(The STarT Back Screening Tool)

Arthritis and Rheumatism 2008 (May 15); 59 (5): 632–641Hill, J. C., Whitehurst, D. G., Lewis, M., Bryan, S., Dunn, K. M., & Foster, N. E. (2011).

Comparison of Stratified Primary Care Management for Low Back Pain

with Current Best Practice (STarT Back): A Randomised Controlled Trial

Lancet. 2011 (Oct 29); 378 (9802): 1560–1571Kilpikoski, S., Airaksinen, O., Kankaanpa, M., Leminen, P., Videman, T., & Alen, M. (2002).

Interexaminer reliability of low back pain assessment using the McKenzie method.

Spine, 27, E207–E214.Long, A., Donelson, R., & Fung, T. (2004).

Does it matter which exercise? A randomized control trial of exercise for low back pain.

Spine, 29, 2593–2602.Long, A., May, S., & Fung, T. (2008).

The comparative prognostic value of directional preference and centralization:

A useful tool for front-line clinicians?

The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 16, 248–254.Main, C. J., Sowden, G., Hill, J. C., Watson, P. J., & Hay, E. M. (2012).

Integrating physical and psychological approaches to treatment in low back pain:

The development and content of the STarT Back trial's ‘high-risk’ intervention

(StarT Back; ISRCTN 37113406).

Physiotherapy, 98, 110–116.May, S. (2007).

Patients' attitudes and beliefs about back pain and its management after physiotherapy

for low back pain.

Physiotherapy Research International, 12, 126–135.May, S., & Aina, A. (2012).

Centralization and directional preference: A systematic review.

Manual Therapy, 17, 497–506.McKenzie, R., & May, S. (2004).

The lumbar spine: Mechanical diagnosis and therapy. 2nd ed.

Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal Publications; 2003.

Phenomenon of spinal symptoms—A systematic review.

Manual Therapy, 9, 134–143.O'Sullivan, P., Caneiro, J. P., O'Keeffe, M., & O'Sullivan, K. (2016).

Unraveling the complexity of low back pain.

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 46, 932–937Petersen, T., Laslett, M., Thorsen, H., Manniche, C., Ekdahl, C., & Jacobsen, S. (2003).

Diagnostic classification of non-specific low back pain.

A new system integrating patho-anatomic and clinical categories.

Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 19, 213–237.SAS Institute Inc (1999).

SAS OnlineDoc®, Version 8.

Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

https://v8doc.sas.com/sashtml/insight/chap39/sect29.htmSowden, G., Hill, J. C., Konstantinou, K., Meenee Khannaa, D., Chris, J. (2012).

IMPaCT Back study team. Targeted treatment in primary care for low back pain:

The treatment system and clinical training programs used in the IMPaCT Back study.

Family Practice, 29, 50–62.Swinkels, I. C., van den Ende, C. H., de Bakker, D., van der Wees, P., Hart, D. (2007).

Clinical databases in physical therapy.

Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 23, 153–167.Von Korff, M., Shortreed, S. M., Saunders, K. W., Leresche, L., Berlin, J. A. (2014).

Comparison of back pain prognostic risk stratification item sets.

The Journal of Pain, 15, 81–89.Werneke, M. W., Hart, D. L., Cutrone, G., Oliver, D., McGill, T., Weinberg, J. (2011).

Association between directional preference and centralization in patients with low back pain.

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 41, 22–31Werneke, M. W., Hart, D. L., George, S. Z., Stratford, P. W., Matheson, J. W. (2009).

Clinical outcomes for patients classified by fear-avoidance beliefs

and centralization phenomenon.

Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90, 768–777.Wideman, T. H., Hill, J. C., Main, C. J., Lewis, M., Sullivan, M. J. (2012).

Comparing the responsiveness of a brief, multidimensional risk screening tool for back pain

to its unidimensional reference standards: The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Pain, 153, 2182–2191.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to McKENZIE METHOD

Since 5-13-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |