Do Participants with Low Back Pain who Respond to Spinal

Manipulative Therapy Differ Biomechanically From

Nonresponders, Untreated Controls or Asymptomatic Controls?This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015 (Sep 1); 40 (17): 1329–1337 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Arnold Y. L. Wong, PT, MPhil, PhD, Eric C. Parent, PT, PhD,

Sukhvinder S. Dhillon, MB, ChB, CCST, Narasimha Prasad, PhD,

and Gregory N. Kawchuk, DC, PhD

Department of Rehabilitation Sciences,

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University,

Kowloon, Hong Kong

Department of Physical Therapy,

University of Alberta,

Alberta, Canada

FROM: University of Alberta ~ 8-31-2015

Depending on whom you ask or what scientific paper you read last, spinal manipulation is either a mercifully quick, effective treatment for low-back pain or a complete waste of time.

It turns out everyone’s right.

Researchers at the University of Alberta have found that spinal manipulation—applying force to move joints to treat pain, a technique most often used by chiropractors and physical therapists—does indeed have immediate benefits for some patients with low-back pain but does not work for others with low-back pain. And though on the surface this latest conflict might appear to muddy the waters further, the results point to the complexity of low-back pain and the need to treat patients differently, says lead author Greg Kawchuk.

“Back pain, just like cancer, is a collection of different kinds of problems. We haven’t been very good at distinguishing who has which problem, so we throw a treatment at people and naively expect that treatment to fix everyone’s back pain,” says Kawchuk, an expert in spine function and professor in the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine who co-wrote the study with U of A colleagues Arnold Wong (now at Hong Kong Polytechnic University), Eric Parent, Sukhvinder Dhillon and Narasimha Prasad.

“This study shows that, just like some people respond differently to a specific medication, there are different groups of people who respond differently to spinal manipulation.”

In a non-randomized control study, individuals with low-back pain received spinal manipulation during two treatment sessions that spanned a week. Participants reported their pain levels and disability levels after spinal manipulation, and researchers used ultrasound, MRI and other diagnostics to measure changes in each participant’s back, including muscle activity, properties within the intervertebral discs, and spinal stiffness.

A control group of participants with low-back pain underwent similar clinical examinations but did not receive spinal manipulation. A third group — those who did not have low-back pain symptoms — were also evaluated.

The people who responded to spinal manipulation reported less pain right away and showed improvement in back muscle thickness, disc diffusion and spinal stiffness. Those changes were great enough to exceed or equal the measures in the control groups and stayed that way for the week of treatment, the research team found. A patient receives spinal manipulation treatment.

Researchers measure back stiffness after a study participant received spinal manipulation.

Conversely, researchers also found that people with back pain who reported no improvement showed no physical changes either—there simply was no effect.

Kawchuk, who practised as a chiropractor before going on to obtain his PhD in biomechanics and bioengineering, said the results do not advocate one way or another for spinal manipulation but help explain why there has been so much conflicting data about its merits.

“Clearly there are some people with a specific type of back pain who are responding to this treatment and there are some people with another type of back pain who do not. But if you don’t know that and you mix those two groups together, you get an artificial average that doesn’t mean anything,” Kawchuk explained.

The research team is still fine-tuning how to distinguish who is a responder or non-responder before spinal manipulation is given; however, this study shows it can be used to identify an effective treatment course.

“Spinal manipulation acts so rapidly in responders that it could be used as a screening tool to help get the right treatment to the right patient at the right time.”

The study did not investigate the long-term effects of spinal manipulation, but this is next on the list for the researchers.STUDY DESIGN: Nonrandomized controlled study.

OBJECTIVE: To determine whether patients with low back pain (LBP) who respond to spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) differ biomechanically from nonresponders, untreated controls or asymptomatic controls.

SUMMARY OF BACKGROUND DATA: Some but not all patients with LBP report improvement in function after SMT. When compared with nonresponders, studies suggest that SMT responders demonstrate significant changes in spinal stiffness, muscle contraction, and disc diffusion. Unfortunately, the significance of these observations remains uncertain given methodological differences between studies including a lack of controls.

METHODS: Participants with LBP and asymptomatic controls attended 3 sessions for 7 days. On sessions 1 and 2, participants with LBP received SMT (+LBP/+SMT, n = 32) whereas asymptomatic controls did not (-LBP/-SMT, n = 57). In these sessions, spinal stiffness and multifidus thickness ratios were obtained before and after SMT and on day 7. Apparent diffusion coefficients from lumbar discs were obtained from +LBP/+SMT participants before and after SMT on session 1 and from an LBP control group that did not receive SMT (+LBP/-SMT, n = 16). +LBP/+SMT participants were dichotomized as responders/nonresponders on the basis of self-reported disability on day 7. A repeated measures analysis of covariance was used to compare apparent diffusion coefficients among responders, nonresponders, and +LBP/-SMT subjects, as well as spinal stiffness or multifidus thickness ratio among responders, nonresponders, and -LBP/-SMT subjects.

RESULTS: After the first SMT, SMT responders displayed statistically significant decreases in spinal stiffness and increases in multifidus thickness ratio sustained for more than 7 days; these findings were not observed in other groups. Similarly, only SMT responders displayed significant post-SMT improvement in apparent diffusion coefficients.

CONCLUSION: Those reporting post-SMT improvement in disability demonstrated simultaneous changes between self-reported and objective measures of spinal function. This coherence did not exist for asymptomatic controls or no-treatment controls. These data imply that SMT impacts biomechanical characteristics within SMT responders not present in all patients with LBP. This work provides a foundation to investigate the heterogeneous nature of LBP, mechanisms underlying differential therapeutic response, and the biomechanical and imaging characteristics defining responders at baseline

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) is a common intervention for low back pain (LBP). Historically, the results of clinical trials designed to evaluate SMT have been mixed [1–5] with some (but not all) participants reporting a benefit. In recent years, growing evidence suggests that these mixed results are due partially to a differential treatment response in patients. [1, 2, 6]

Although some have suggested that a differential response of participants with LBP to SMT could be caused by psychosocial factors (e.g. , expectation), [7, 8] others have developed and validated a clinical prediction rule (CPR) to identify likely responders to SMT on the basis of clinical characteristics. [1, 6]

This work was based on the observation that patients with LBP who self-reported clinically significant improvement in the modified Oswestry Disability Index (mODI) displayed at least 4 of 5 specific clinical characteristics (see Supplemental Digital Content Appendix I).

After this work, Fritz and coworkers [9] demonstrated that CPR status might be related to LBP disability through its relation to lumbar multifidus (LM) contraction thickness. They also found that post-SMT improvement of the mODI score for more than 1 week was associated with(1) immediate decrease in the spinal stiffness at L3 and

(2) immediate increase in the LM contraction thickness at L4–L5 during contralateral arm lifting. [9, 10]Intervertebral disc (IVD) properties have also demonstrated a similar association with those who respond positively to SMT. Beattie and coworkers [11] found that patients with LBP who experienced clinically significant post-SMT reduction in pain showed statistically significant increases in water diffusion within the L1–L2, L2–L3, and L5–S1 discs, whereas patients without reduction in post-SMT LBP did not.

Individually, these prior studies suggest that several specific biomechanical measures change in SMT responders and are consistent with the assumption that SMT exerts its therapeutic effect through biomechanical and/or neurophysiological mechanisms. [12–14] Unfortunately, our understanding of the mechanisms underlying differential post-SMT responses in patients with LBP remains limited for several reasons.

First, these studies employed different methodologies in different samples. It remains unknown whether these same post-SMT changes would exist within the same sample. Second, no prior study has included specific control groups to establish whether post-SMT biomechanical changes significantly differ from the variance in these same measures. Third, prior studies used the minimal clinically important difference to assess clinical significance. Although the minimal clinically important difference is a useful tool, it is an approximation. [15]

Methodologically, if asymptomatic controls are used instead, then the absolute magnitudes of outcome measures in post-treatment participants can be compared with outcome magnitudes in asymptomatic controls for a more robust estimation of clinical relevance. Finally, it is unknown whether as a group, post-SMT changes in spinal stiffness, muscle contraction, and disc diffusion are related to LBP disability after 7 days. [9, 10] Assessment of disability at 1 week is ideal as it predicts clinical outcomes at 1 and 3 months. [16]

As discussed previously, the objective of this study was to determine whether patients with LBP who respond to SMT differ biomechanically from nonresponders, untreated controls, or asymptomatic controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants aged 18 to 60 years with or without LBP were recruited from advertisements in local health care facilities and universities. Inclusion criteria for participants with LBP were LBP with or without leg symptoms, LBP intensity of at least 2 on the 11-point numeric pain rating scale, [17] and mODI score of at least 20%. [9] Exclusion criteria were “red flag” conditions, signs of nerve root compression, scoliosis, osteoporosis, joint hypermobility syndrome, previous lumbosacral surgery, and SMT/stabilization exercise treatment in the last 4 weeks.

Individuals with LBP were enrolled into either the treatment (+ LBP/+ SMT) or untreated LBP control (+LBP/-SMT) group if they possessed either(a) 4 or more of 5 clinical prediction rule (CPR) characteristics (predicted responders) (see Supplemental Digital Content Appendix I) or

(b) 2 or less CPR characteristics (predicted nonresponders). [9]Individuals with exactly 3 characteristics were excluded. [9, 10] Approximately equal proportions of CPR-predicted responders (43.8%) and non-responders (56.2%) were enrolled into the + LBP/+ SMT or + LBP/– SMT group (see later). Importantly, the same screening strategy for recruiting potential responders and nonresponders has been used in prior SMT studies. [9, 10] Using the same recruitment methods, asymptomatic controls were enrolled with inclusion criteria of no current LBP and no history of LBP that required sick leave in the last 12 months. Participants provided informed consent via processes approved by the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta.

Figure 1 Protocol

Participants With LBP Receiving SMT (+ LBP/+ SMT) Thirty-two participants with LBP attended 3 sessions for more than 7 days (Figure 1). On session 1 (between 8:00 am and 12:00 pm), participants with LBP reported baseline demographics, underwent a clinical examination, and completed the mODI. In addition, 3 biomechanical outcome measures were collected before, and after the provision of SMT: spinal stiffness through mechanized indentation, LM contraction thickness from ultrasonography, and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of each lumbar disc via diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). On session 2 (3–4 d later, from 0800 to 1200), the same variables were repeated with the exception of ADC. During session 3 (day 7), only spinal stiffness and LM contraction were collected together with the mODI. The data collection was arranged in the morning to minimize the potential diurnal fluctuation in disc diffusion though prior research revealed no significant diurnal change in ADC values in the center of the nucleus pulposus of lumbar discs. [18]

Participants With LBP Not Receiving SMT (+ LBP/– SMT) A group of 16 LBP controls were taken through the same procedures outlined for session 1 but did not receive SMT or any further sessions (Figure 1).

Asymptomatic Participants Not Receiving SMT (– LBP/– SMT) Fifty-nine asymptomatic participants completed sessions 1, 2, and 3 without SMT and without DWI (Figure 1). Based on assessment at session 3, + LBP/+ SMT participants were classified as SMT responders (a cutoff of ≥ 30% reduction in baseline mODI scores) or nonresponders (< 30% reduction in baseline mODI scores). This cutoff represents an estimation of the minimal clinically important change in LBP-related disability. [19] The ADC values in the first and second scans of + LBP/– SMT participants were compared with those of SMT responders/non-responders. The spinal stiffness and LM thickness of SMT responders/nonresponders at various measurement time points were compared with those of –LBP/– SMT participants.

Outcome Measures

LBP-related disability was measured by mODI given its high reliability, validity, and responsiveness. [20]

Spinal stiffness was measured by a mechanical indentation device whose operation and reliability have been published previously (Figure 2). [21] Briefly, the device consists of a motorized indenter controlled by customized software (National Instruments, Austin, TX) used to control the loading velocity (2 mm/s) and collect force and displacement signals. [21] The L3 spinous process was identified in the participant in the prone position by ultrasonography. Spinal stiffness at the L3 level was measured during held exhalation. [9, 21] Stiffness was calculated as the slope of the force-displacement curve from a 5N preload to a maximal load of 60N. [9, 21] Three indentations were performed before, and after, SMT applications, with the mean of each set of 3 trials used for statistical analysis.

The LM thickness ratio was quantified at L3–L4 and L4–L5 by ultrasonography — a valid proxy for LM activity having high reliability. [22–24] Ultrasonography was performed by a single examiner using video from a SonixTouch Q + (Ultrasonix, Peabody, MA) and a 5-MHz curvilinear transducer. For participants with LBP, ultrasonography was performed on the more symptomatic side and on a random side for asymptomatic participants. Each participant in the prone position raised a weight (1.5–3.0 lb) 3 times in the contralateral hand to touch a bar fixed at a 5-cm height [22] toward creating a 30% maximal voluntary contraction. [23]

From the recorded video, a blinded examiner selected the frame from the video, showing the LM at rest and then again at maximal contraction thickness. The mean of 3 LM thickness ratios was used for each measurement point in the protocol where thickness ratio was calculated as thickness contracted – thickness rest/thickness rest × 100%, using the distance between the posterior-most tip of the target facet joint and the thoracolumbar fascia (Figure 3, Image J software, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). [22, 25] For all imaging, the ultrasound transducer was fixed in the same position via a mechanized arm.

Figure 2. Mechanical spinal stiffness test.

Figure 3. Mmeasurement.

LM indicates lumbar multifidus.

Wach a video of this measuring device in action

Table 1

Figure 4 All participants with LBP underwent DWI with a 1.5 Tesla imager (MAGNETOM Symphony, Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA) at the beginning and the end of their first/single visit. Scan parameters are listed in Table 1. Sagittal diffusion-weighted images were acquired using a single shot, dual spin echo, echo-planar imaging acquisition with multi-element spine coils and abdominal coils. A total of 15 sagittal slices were obtained per participant. For each slice, DWI was obtained by applying diffusion gradients in 3 orthogonal directions. [26] The mean ADC was constructed on the basis of averages of signal intensity from 3 directional diffusion-weighted images. [26]

To quantify lumbar IVD diffusion, the ADCs of all lumbar IVDs were measured from the midsagittal ADC maps. A blinded examiner then used a customized program (MathWorks, Natick, MA) to place a 40-mm 2 circular region of interest (ROI) in the central, nuclear portion of each lumbar IVD to minimize the inclusion of vertebral bodies and/or endplates (Figure 4). The program calculated ADC from signal intensity within the ROI. If the ROI diameter larger than the IVD height, the segment was excluded. [26, 27] It is thought that ADC is a proxy for IVD diffusion; a high ADC value indicated high IVD diffusion. [28]

To establish the intrarater reliability of ADC measurements, 3 weeks after the initial ADC measurements, the examiner who was blinded to previous measurement results repeated the ADC measurements on the scans of 16 randomly selected participants.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy

A standardized application of SMT as described by the CPR derivation study was provided to relevant participants (see Supplemental Digital Content Appendix 2). [1, 6] This technique applies a postero-inferior thrust to the patient's pelvis. A maximum of 2 thrusts were delivered to each side of the subject during each session.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic data and outcome values for each group at each assessment. Continuous and categorical demographic data of various groups were compared by 1-way analysis of variance and χ2 test, respectively. Baseline physical characteristics of LBP and asymptomatic participants were compared by independent t tests. The significance level was set at 0.05.

The intraobserver reliability of ADC measurements at each vertebral level was analyzed by intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC 3,1).

The serial changes in spinal stiffness and LM thickness ratios among groups were analyzed by separate repeated measures analyses of covariance, with time as a repeated measure, and group (LBP status and responder/nonresponder as defined by mODI) as the between-subject factor. The assumptions of analyses of covariance were evaluated. If the assumption of sphericity was violated, the Greehouse-Geisser correction was chosen to interpret the results. [29] The post hoc tests included simple effect tests and tetrad analyses, [30] with Bonferroni adjustment. Separate analyses of covariance were used to analyze the baseline and changes in diffusion at various IVD levels among LBP controls, responders, and nonresponders after the first SMT. The covariates for all tests were age, sex, and body mass index because prior research has suggested that these covariates may affect the measured physical variables. [9–11, 28, 31, 32]

Pearson correlation was calculated to analyze the associations among the percent change in spinal stiffness, LM thickness ratios, and ADC values after the first SMT in +LBP/+ SMT participants using pooled data. The effect sizes of correlation were considered to be small, medium, and large if coefficients were 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50, respectively. [33]

RESULTS

Group Characteristics

Although no participant dropped out from the +LBP/+ SMT or +LBP/– SMT group, 2 asymptomatic participants dropped out after session 1 because of time conflicts, leaving 57 asymptomatic controls in this study. The LM muscle boundaries of 1 LBP participant and 2 asymptomatic participants were unidentifiable, leaving complete data of ultrasonography on 86 participants. After assessment of mODI results, 15 participants with LBP were classified as SMT responders and 17 as nonresponders.

Reliability of ADC Measurements

Of the 80 IVDs from 16 participants evaluated in this study, 4 IVDs were excluded from the ADC measurements because the disc space was smaller than the ROI. The intraclass correlation coefficient estimates ranged from 0.97 to 0.98.

Baseline Characteristics Between Groups

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of participants are depicted in Table 2. Compared with participants with LBP, asymptomatic controls had significantly less prior LBP episodes and lower mODI scores. At baseline, there was no significant difference in spinal stiffness or LM thickness ratio among the –LBP/– SMT, responder, and nonresponder groups (Table 2). There was no significant difference in baseline lumbar IVD diffusion among +LBP/– SMT controls, responders, and nonresponders.

Post-SMT Change in Spinal Stiffness

The spinal stiffness of SMT responders was significantly reduced after each SMT (interaction for group-by-time: F 5,332 = 10.50, P < 0.01, post hoc after each SMT, P < 0.05) (Figure 5), whereas the SMT non-responders and –LBP/–SMT group showed no such change. These changes were sustained at day 7. Post hoc tests demonstrated that the responders’ mean spinal stiffness at session 3 was significantly lower than their baseline values (average difference: – 0.255 N/mm, 95% confidence interval [CI]: – 0.079 to – 0.431 N/mm).

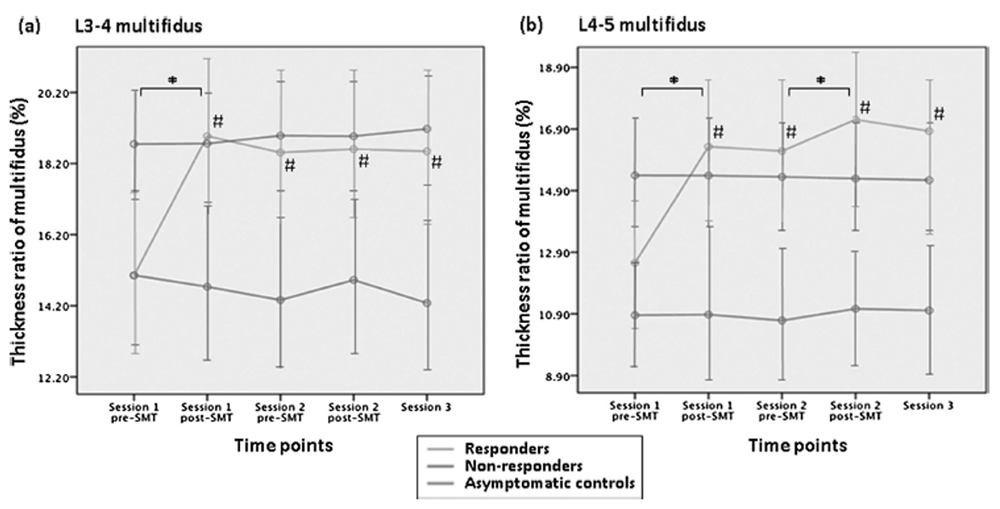

Post-SMT Change in LM Thickness Ratios

SMT responders demonstrated significant increases in LM thickness ratios after the first SMT (interaction for group-bytime for L3–L4: F 8,320 = 22.33, P < 0.01; L4–L5: F 8,320 = 18.21, P < 0.01, post hoc test, P < 0.01) (Figure 6 A, B). These improved post-SMT LM thickness ratios were sustained for more than 1 week (average difference of thickness ratio at L3–L4 LM: 3.83%, CI: 2.62%–5.04%; mean difference of L3–L4 LM: 4.38%, CI: 2.77%–5.98%). No similar change was noted in the non-responders and the –LBP/–SMT group.

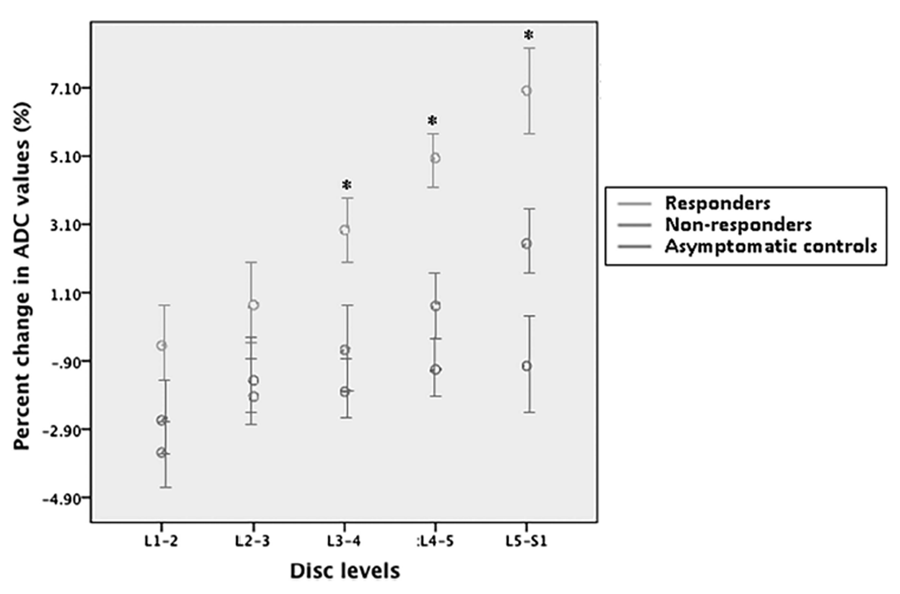

Post-SMT Change in IVD Diffusion

The inferior 3 lumbar IVDs showed significant betweengroup changes in ADC values (L3–L4: F 2 ,42 = 8.66, P < 0.01; L4–L5: F 2,41 = 19.93, P < 0.01; L5–S1: F 2,41 = 6.45, P < 0.01) (Figure 7). Post hoc tests showed that only SMT responders had significant increases in diffusion within the L3–L4, L4–L5, and L5–S1 discs (P < 0.01) whereas no significant change was noted in the nonresponders, nor in the –LBP/–SMT group (average differences in percent changes of ADC values between responders and +LBP/– SMT group at L3–L4 disc: 4.91%, CI: 1.94%–7.87%; at L4–L5 disc: 6.50%, CI: 3.88%–9.13%; and at L5–S1 disc: 8.15%, CI: 4.14%–12.15%).

Post-SMT Associations Between Outcome Change Scores

After SMT application on session 1, decreases in spinal stiffness of participants with LBP were significantly associated with an increased LM thickness ratio at all measured levels (r = – 0.59, P < 0.01) as well as with ADC values in the discs of L3–L4 and L4–L5 (r = – 0.42 and – 0.50, respectively, P < 0.01). Similarly, the percent increase in LM thickness ratio after the first SMT application was related to the corresponding increase in L3–L4 and L4–L5 disc diffusion (r = 0.35–0.47) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The current study is the first to determine that multiple biomechanical outcomes (physical and imaging) respond differently in those reporting improvement after SMT compared with those who do not report improvement. Importantly, key comparison and control groups were included in our methodology to minimize the possibility that our observations were due to measurement variability (+LBP/–SMT). Our results consist of several important findings. First, after 1 SMT application, SMT responders show immediate and sustained alterations in spinal biomechanics. These post-SMT changes are statistically significant compared with nonresponders and overlap with measures observed in asymptomatic controls. The differential responses of patients with LBP imply that certain unidentified biomechanical characteristics of non-responders (e.g., spinal degeneration) may impede the effect of SMT.

Alternatively, the large between-subject variations (standard deviations) in spinal stiffness and LM thickness ratios at baseline (Table 2), the small to medium effect sizes of these comparisons, or low statistical power might have prevented the identification of significant between-group difference in these characteristics at baseline. Our results justify continued investigations into characteristics defining SMT responders at baseline.

Several studies have demonstrated that various biomechanics of SMT responders change compared with non-responders. [9–11]

Comparatively, our results are a significant development in that they(1) demonstrate that the various outcome measures that were responsive in prior individual investigations are also responsive when studied with a unified methodology in the same subjects and that

(2) these same measures are moderately to strongly associated with each other.Furthermore, our addition of untreated controls allows for more robust conclusions regarding a selective treatment response between SMT responders and nonresponders. Specifically, the inclusion of non-treatment controls (+LBP/–SMT) showed that variation due to measurement or due to the LBP itself is insufficient to confound post-SMT changes in the responder group. Given that SMT responders showed significantly greater changes in biomechanical outcomes than nonresponders, we can say with increased confidence that changes in the SMT responders are more likely the result of SMT and less likely from treatment variability, measurement variability, or variability in the target condition. In other words, the biomechanical changes in SMT responders were clinically relevant. Importantly, the observation that self-reported measures of function are coherent with objective, physical measures in both the SMT responders and non-responders implies that self-reports of spinal function and spinal biomechanics are related.

The observation that a specific group of participants responds to SMT is consistent with prior studies that show a change in stiffness and/or LM thickness ratio after SMT and, in particular, those studies that show a varied therapeutic benefit in subjects with nonspecific LBP. [9, 10, 34] This suggests that SMT is not a broad-spectrum therapy but one that impacts factors within SMT responders that are not present in all persons with LBP. Given the observed correlations between our biomechanical outcome measures (spinal stiffness, LM thickness ratio, ADC), we would suggest that the differential response of participants with LBP to SMT is based on a biomechanical mechanism. Although the mechanism remains unknown, it is biologically plausible that decreases in spinal stiffness may permit increased disc diffusion and increased segmental motion enabling increased LM thickness ratios. The increased disc diffusion may also improve IVD health and yields favorable clinical outcomes. [35] Although our data do not prove the existence of LBP subgroups, they do reinforce that LBP is a heterogeneous condition and that in the short term, SMT does not equally affect those who experience LBP.

As with all studies, this investigation has limitations that restrict its interpretation. First, ADC measures were taken only in participants with LBP. We assumed that the diffusion within the discs of asymptomatic participants would not change significantly given prior research. [26] Importantly, we did obtain ADC values from +LBP/–SMT to control for the magnitude of ADC measurement variability over the time it would have taken to provide SMT in the +LBP/+SMT group. The measured ADC values were also comparable with prior studies. [27, 36] Second, SMT was not given to asymptomatic participants, which may have allowed us to further determine the differential impact of SMT (i.e., Do asymptomatic individuals show post-SMT decreased stiffness or are asymptomatic stiffness values already minimal?). Third, as the pain intensity and disability level of the +LBP/+SMT and +LBP/–SMT groups were relatively low, our results may not be generalized to individuals with severe LBP.

Our results demonstrate that those reporting post-SMT improvement in disability have coherent changes in multiple, objective measures of spinal biomechanics. This same coherence does not exist for asymptomatic controls or no-treatment symptomatic controls. Our data further support a differential effect of SMT on a specific constellation of biomechanical outcomes that are not responsive in all patients with LBP. This work provides a foundation from which to investigate the heterogeneous nature of LBP, the mechanisms underlying differential therapeutic response, and the biomechanical characteristics defining the responders at baseline.

Key Points

Responders to spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain are characterized by

an immediate and sustainable decrease in spinal stiffness and an increase in lumbar

multifidus muscle thickness ratio.In comparison, spinal manipulative therapy nonresponders and asymptomatic

controls showed no change in spinal stiffness or lumbar multifidus contraction ratio.Immediate enhancement of lumbar disc diffusion was observed after the first spinal

manipulative therapy in participants who reported improved back pain–related

disability at 1 week.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Magnetic Imaging Consultants for providing advice and scan services. The authors are very grateful to the River Valley Health Clinic for providing professional SMT and clinical space. They also thank Mr. Karl Brandt and Ms. Carolyn Berendt for assisting the coding and decoding of various spinal stiffness, ultrasound imaging, and magnetic resonance imaging files. Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appearing in the printed text are provided in the HTML and PDF version of this articleReferences:

Childs JD, Fritz JM, Flynn TW, Irrgang JJ, Johnson KK, Majkowski GR, et al.

A Clinical Prediction Rule To Identify Patients With Low Back Pain Most Likely To Benefit

from Spinal Manipulation: A Validation Study

Annals of Internal Medicine 2004 (Dec 21); 141 (12): 920–928Cleland J, Fritz J, Whitman J, et al.

The use of a lumbar spine manipulation technique by physical therapists in patients who satisfy a clinical prediction rule: a case series.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006; 36: 209–14.Dagenais, S., Gay, R. E., Tricco, A. C., Freeman, M. D., & Mayer, J. M.

NASS Contemporary Concepts in Spine Care:

Spinal Manipulation Therapy for Acute Low Back Pain

The Spine Journal 2010 (Oct); 10 (10): 918-940Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Assendelft WJJ, et al.

Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low-back pain: an update of a Cochrane review.

Spine 2011; 36: E825–46.von HeymannWJ, Schloemer P, Timm J, Muehlbauer B.

Spinal High-velocity Low Amplitude Manipulation in Acute Nonspecific Low Back Pain:

A Double-blinded Randomized Controlled Trial in Comparison With

Diclofenac and Placebo

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013 (Apr 1); 38 (7): 540–548Flynn T, Fritz J, Whitman J, et al.

A Clinical Prediction Rule for Classifying Patients with Low Back Pain

who Demonstrate Short-term Improvement with Spinal Manipulation

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002 (Dec 15); 27 (24): 2835–2843Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, et al.

A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability.

Pain 1993; 52: 157–68.Mondloch MV, Cole DC, Frank JW.

Does how you do depend on how you think you“ll do? A systematic review of the evidence for a relation between patients” recovery expectations and health outcomes.

Can Med Assoc J 2001; 165: 174–9.Fritz JM, Koppenhaver SL, Kawchuk GN, Teyhen DS, Hebert JJ, Childs JD.

Preliminary Investigation of the Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of Manipulation:

Exploration of a Multivariate Model Including Spinal Stiffness,

Multifidus Recruitment, and Clinical Findings

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011 (Oct 1); 36 (21): 1772-1781Koppenhaver SL, Fritz JM, Hebert JJ, et al.

Association between changes in abdominal and lumbar multifidus muscle thickness and clinical improvement after spinal manipulation.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011; 41: 389–99.Beattie PF, Butts R, Donley JW, et al.

The within-session change in low back pain intensity following spinal manipulative therapy is related to differences in diffusion of water in the intervertebral discs of the upper lumbar spine and L5-S1.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2014; 44: 19–29.Cramer G, Budgell B, Henderson C, et al.

Basic Science Research Related to Chiropractic Spinal Adjusting:

The State of the Art and Recommendations Revisited

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006 (Nov); 29 (9): 726–761Colloca CJ, Keller TS, Gunzburg R.

Neuromechanical Characterization Of In Vivo Lumbar Spinal Manipulation.

Part II. Neurophysiological Response

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003 (Nov); 26 (9): 579–591Lalanne K, Lafond D, Descarreaux M.

Modulation of the flexion-relaxation response by spinal manipulative therapy: a control group study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009; 32: 203–9.Simon LS, Evans C, Katz N, et al.

Preliminary development of a responder index for chronic low back pain.

J Rheumatol 2007; 34: 1386–91.Peterson CK, Bolton J, Humphreys BK.

Predictors of Improvement in Patients With Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain

Undergoing Chiropractic Treatment

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012 (Sep); 35 (7): 525-533Beattie PF, Arnot CF, Donlex J, et al.

The immediate reduction in low back pain intensity following lumbar joint mobilization and prone press-ups is associated with increased diffusion of water in the L5-S1 intervertebral disc.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010; 40: 256–64.Ludescher B, Effelsberg J, Martirosian P, et al.

T2- and diffusion- maps reveal diurnal changes of intervertebral disc composition: an in vivo MRI study at 1.5 Tesla.

J Magn Reson Imaging 2008; 28: 252–7.Ostelo RWJG, Deyo RA, Stratford P, et al.

Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change.

Spine 2008; 33: 90–4.Fritz J, Irrgang J.

A comparison of a modified Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire and the Quebec back pain disability scale.

Phys Ther 2001; 81: 776–88.Wong AY, Kawchuk G, Parent E, et al.

Within-and between-day reliability of spinal stiffness measurements obtained using a computer controlled mechanical indenter in individuals with and without low back pain.

Man Ther 2013; 18: 395–402.Wong AYL, Parent E, Kawchuk G.

Reliability of 2 ultrasonic imaging analysis methods in quantifying lumbar multifidus thickness.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2013; 43: 251–62.Kiesel K, Uhl T, Underwood F, et al.

Measurement of lumbar multifidus muscle contraction with rehabilitative ultrasound imaging.

Man Ther 2007; 12: 161–6.Koppenhaver S, Hebert J, Parent E, et al.

Rehabilitative ultrasound imaging is a valid measure of trunk muscle size and activation during most isometric sub-maximal contractions: a systematic review.

Aust J Physiother 2009; 55: 153–69.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW.

NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis.

Nat Methods 2012; 9: 671–5.Beattie PF, Morgan PS, Peters D.

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of normal and degenerative lumbar intervertebral discs: a new method to potentially quantify the physiologic effect of physical therapy intervention.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008; 38: 42–9.Kealey SM, Aho T, Delong D, et al.

Assessment of apparent diffusion coefficient in normal and degenerated intervertebral lumbar disks: initial experience.

Radiology 2005; 235: 569–74.Antoniou J, Demers CN, Beaudoin G, et al.

Apparent diffusion coefficient of intervertebral discs related to matrix composition and integrity.

Magn Reson Imaging 2004; 22: 963–72.Portney L, Watkins M.

Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. 3rd ed.

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2009.Marascuilo L, Levin J.

Appropriate post hoc comparisons for interaction and nested hypotheses in analysis of variance designs: the elimination of type IV errors.

Am Educ Res J 1970; 7: 397–421.Miller JA, Schmatz C, Schultz AB.

Lumbar disc degeneration: correlation with age, sex, and spine level in 600 autopsy specimens.

Spine 1988; 13: 173–8.Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Chan D, et al.

The association of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration on magnetic resonance imaging with body mass index in overweight and obese adults: a population based study.

Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 1488–96.Cohen J.

Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.Brenner AK, Gill NW, Buscema CJ, et al.

Improved activation of lumbar multifidus following spinal manipulation: a case report applying rehabilitative ultrasound imaging.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2007; 37: 613–9.Beattie PF.

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the musculoskeletal system: an emerging technology with potential to impact clinical decision making.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011; 41: 887–95.Niinimäki J, Korkiakoski A, Ojala O, et al.

Association between visual degeneration of intervertebral discs and the apparent diffusion coefficient.

Magn Reson Imaging 2009; 27: 641–7.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to CLINICAL PREDICTION RULE

Since 9-01-2015

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |