Looking Ahead: Chronic Spinal Pain Management This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Pain Research 2017 (Aug 30); 10: 2089–2095 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Gregory F Parkin-Smith, Stephanie J Davies, Lyndon G Amorin-Woods

School of Health Professions,

Murdoch University,

Perth, WA, Australia;The other day, we oversaw a seminar on pain management for a local consumer pain group, where all consumers (patients) in attendance were experiencing chronic, persistent spinal pain. Each person had a unique story, and their experience and perceived cause of their pain differed. The quality of life in all these consumers was markedly reduced, which was the only clear similarity, confirming that there may be some similarities in the pain experience, but the pain experience was more often unique and individual. These consumers’ criticisms of care services were consistent, however, with dissatisfaction with their access to care and overall management of their pain. They described variable and often difficult access, limited continuity of care, they were often not taken seriously by health care providers, they received scant information about chronic pain and its prognosis and there were often noteworthy variations in the treatment they received.

We agree that these criticisms are commonplace and a frequent gripe directed at health care practitioners about the “system.” [1] Moreover, the problems associated with care delivery are confounded by a number of patient/consumer factors, such as lifestyle habits, nutrition, body weight, depression, health literacy, geographical isolation and poor socioeconomic conditions, making the management of persistent pain even more complicated. [2] There is no doubt that, in the future, matching the care service and treatment with the individual patient will become an essential component of care services, as has been implied in published research. [3–6]

Health care practitioners involved in the triage and management of patients with persistent spinal pain will need to become more vigilant about individualizing and coordinating care for each patient, to achieve the best possible outcomes. For example, Cecchi et al concluded that patients with chronic (persistent) lower baseline pain (LBP)- related disability predicted “nonresponse” to standard physiotherapy, but not to spinal manipulation (an intervention commonly employed by chiropractors [7–9]), implying that spinal manipulation should be considered as a first-line conservative treatment. [9] We note that spinal manipulation is now suggested as the first-line intervention by Deyo, [10] since not a single study examined in a recent systematic review found that spinal manipulation was less effective than conventional care. [11]

Garcia et al, [12] conversely, showed that high pain intensity may be an important treatment effect modifier for patients with chronic low back pain receiving Mckenzie therapy (a treatment frequently used by physiotherapists). These examples demonstrate the importance of matching treatments with the characteristics of the patient.

Similarly, identifying potential pain generators using diagnostic low-risk interventional pain procedures by precise anatomical instillation of local anesthetics informs the probability of subsequent therapeutic low-risk interventional pain procedures providing medium- to long-term pain relief for that individual. The potential to provide a therapeutic window, for months or years, can enable individuals to continue with evidence-informed behavioral change to achieve the patient’s short- and long-term goals. Interventional pain procedures are rarely performed in isolation because the procedure is only one part of a broader pain management plan.

The person in pain, prior to considering an interventional pain procedure, is ideally engaged in their own “prehabilitation,” which is the process of enhancing functional capacity of the individual to enable him or her to recover more quickly following a procedure. [13] We suggest that the sequence of interventions first involves patient assessment (history, examination, investigations, screening questionnaires, information from previous health care professionals), from which follows pain options that are relevant and available to the individual patient, which results in a pain management plan that is agreed and understood by both the patient (and their significant others) and treating practitioner and communicated to the other health care professionals (coaches). If a person in pain does not currently have a well-organized team providing evidence-based care, then their medical service will need to offer suggestions and coordinate local available options to form a virtual health care pain team.

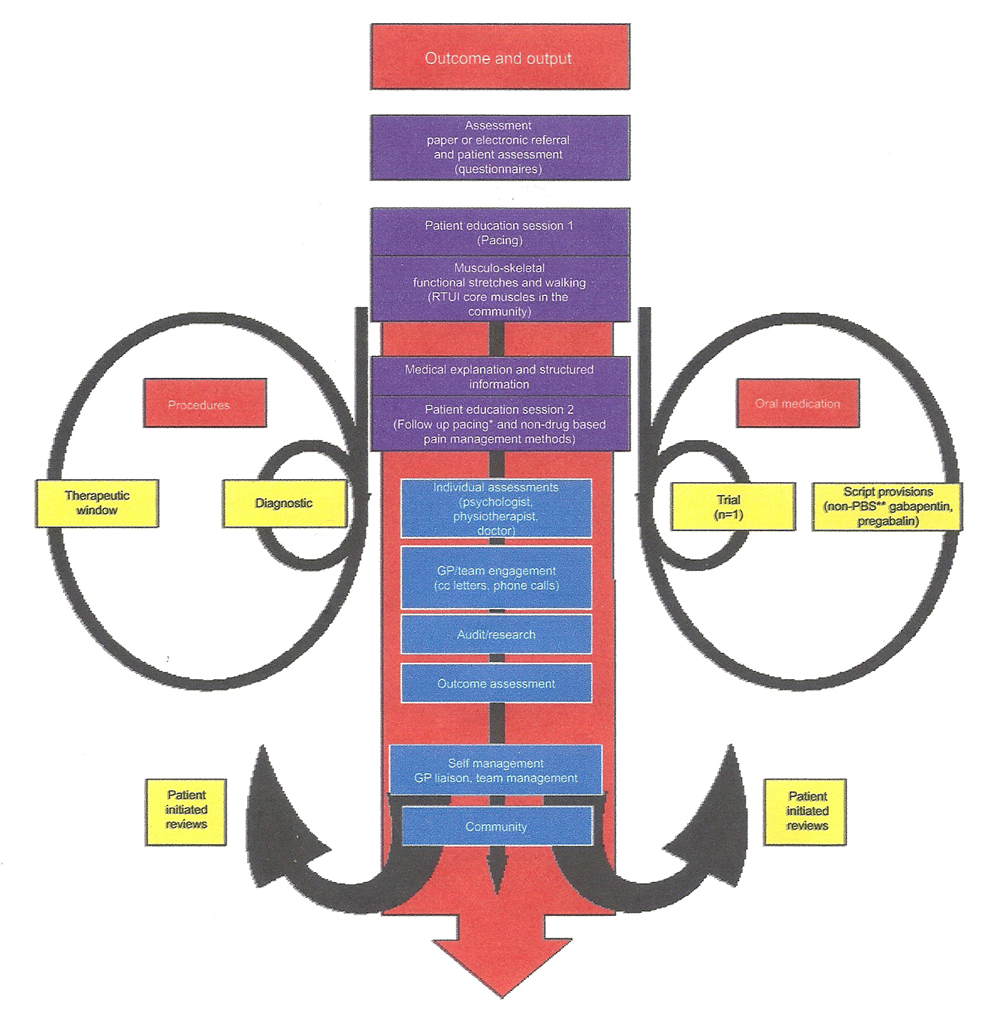

Figure 1 flow chart, is an example of the process of care service provision and the patient journey for the management of chronic spinal pain. Although interventional pain procedures have been utilized for many decades, it is not easy to find precise definitions. Specifically, the distinction between diagnostic and therapeutic procedures is often opaque, and so we have provided our definitions to reduce miscommunication between health care professionals (definitions are listed at the end of this article).

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of an example

of the patient journey and service

processes for chronic pain management.

We would like to draw attention to behavioral changes such as non-sweating movements including real-time imaging for retraining multifidus and transversus abdominis and daily walking, and mindfulness which may all play a role in reducing fear, anxiety and threat. [14, 15] We postulate increasing control and reducing threat, thereby reducing the threat value of pain, can reduce the “other changeable pain” called alloplastic pain for which the glial-modulated immune response (GMIR) is key. Understanding the glial activation in pain pathways may well be key to reducing persistent pain, [16] with palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) which is an endogenous lipid modulator in animals and human beings and has been evaluated since the 1970s as an anti-inflammatory and analgesic drug in more than 30 clinical trials, in a total of ~6,000 [17] patients, including eight clinical trials for nerve entrapment. In one pivotal, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 636 sciatic pain patients, the number needed to treat (NNT) to reach 50% pain reduction compared to baseline was NNT=1.5 after 3 weeks of treatment. [18] This emerging evidence is of interest as no drug interactions or troublesome side effects have been described so far.

In addition, the emerging biology of pulsed radiofrequency neurotomies is unique in that it provides pain relief without causing significant damage to nervous tissue, with animal studies demonstrating modulation of pain transmission in the spinal nerves and spinal cord by a range of mechanisms including modulating gene expression [19] and microglial neurotransmitters. [20–22] These emerging concepts in the literature start to provide biological mechanisms to the use of pulsed radiofrequency modalities for people with spinal pain.

Decades worth of research outcomes suggests that knowledge and guidelines related to both acute and chronic spinal pain are now available [22, 23] – certainly enough to inform practice and the implementation of evidence-informed care services for persistent spinal pain. New policy documents have emerged in Australia, for example, the Spinal Pain Model of Care and the Framework for Chronic Pain, [25, 26] along with published recommendations from recent systematic reviews. For example, exercise, tai chi, yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction and other psychological therapies, spinal manipulation and massage, acupuncture, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; although less effective than previously reported), duloxetine, tramadol and skeletal muscle relaxants (short-term relief only) seem to have a positive role. Yet, commonly encountered treatments, such as passive physical therapies (interferential therapy, short-wave diathermy, traction, ultrasound, lumbar supports, taping, electrical muscle stimulations), opioids (the evidence is very limited for their efficacy), paracetamol, benzodiazepines, systemic corticosteroids, tricyclic and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants, do not seem to contribute much to outcomes. [27, 28]

It is fair to say that we have attended numerous seminars and discussions (such as the working groups and forums in Western Australia [WA] that culminated in the WA Framework for Persistent Pain [2016–2021]), [26] all of which are saying much the same things and consistently offering similar recommendations about chronic spinal pain care. There is ample written about the contemporary approach and context of pain management, such as the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ pain management contextual statement. [29] Therefore, the future of persistent pain management is less about doing more research and producing more guidelines, although research continues to be important, but rather about implementation of existing care frameworks and models of care [30–32] with a view to obtaining better outcomes for patients at a reasonable cost. It is very likely, indeed desirable, that care frameworks and models of care will evolve and be updated every 5–6 years, so stakeholders should keep an eye out and keep themselves informed as to how care services are changing.

The health care literature convincingly reports that coordinated, multidisciplinary and multimodal care, at the right level, is desired to achieve the best possible outcomes for patients and is very likely to be cost-effective. [33] The challenge now is to have persistent spinal pain fully acknowledged as a legitimate chronic condition by both health care providers and policy makers/payers and have evidence-informed, cost-efficient care delivered in the manner described in published frameworks and models of care. Despite the complexity of spinal pain and its management, as with most chronic diseases, the potential workforce and services can and must be made available with appropriate attention, planning and leadership, with a view to improving accessibility to appropriate care early in the development of the spinal pain condition. The consequences are a large population of chronic pain sufferers, worsened by age-related comorbidities, which will be a tremendous burden and cost to the health care system, not to mention the personal suffering of the individual and their carers.

Getting access to the right care at the right time is critical, but the right multidisciplinary team is currently the elusive goal of contemporary spinal pain management. In Australia, waiting times for pain services and specialist appointment may run into many months, if not longer, thereby missing the opportunity for timely treatment. [34] The problem does not lie with access to pain medication/analgesics per se; these may be prescribed by general practitioners (GPs)/ family physicians, indeed already too often or too much, [35] but rather with artful analgesic prescribing and coordinated multimodal treatments within a multidisciplinary setting. We know that spinal pain, according to various reports, such as from the Australian BEACH (Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health) project, is common and that analgesics for it are among two of the top five most commonly prescribed medications. [36] Upshur et al [37] showed that 37.5% of adult appointments in a typical GP’s week involved chronic pain complaints, comprising back pain (23.6%), followed by joint pain (17.1%), headache (12.1%), generalized pain (7.8%) and neck pain (7.5%). Indeed, the proposed approach and management for pain are eloquently summarized in numerous papers directed at health care practitioners, such as by Wan [38] and Goucke [39] yet most doctors are dissatisfied with outcomes and uncomfortable managing chronic pain. [40] Clearly, there is a gap in care service which appears not to be related to examination, diagnosis or analgesic prescribing, but due to “something else,” which we believe is related to proper triage of persons with pain, which would include questionnaires and assessment, and the access of these persons to the appropriate level of multidisciplinary care at the soonest opportunity.

So, how may pain services be delivered in the future to comply with models of care and frameworks while reconciling the challenges of a complex pain service, including that of funding? The idea, of course, is to create a sustainable, comprehensive service with sufficient incentive and reward for the participating workforce. To this end, the coauthors agree that there is likely to be a mixed business model incorporating both the private and public sectors, but on a more community and patient-centric basis, with funds returned to front-line service delivery for integrated interprofessional pain services. This approach would reduce middle management (reducing management costs) and be subject to far less politics, as has been encountered with the poly- or super-clinic concept, while still being able to collaborate with relevant local and state government and nongovernment organizations.

The “third way” ideology for the management of complex spinal pain may have relevance, particularly when it comes to the funding/payment for services. In theory, the “third-way” ideology attempts to graft the traditional concerns about equality and social justice into an economic system based on free markets, thereby implying a mix of public and private health care models. That implies the use of both public and private funding to cover the expenses for care services, where there are government funding or rebates for care services, but the patient themselves also pays a portion of the costs. [41, 42] With a mixed-model business approach and using contemporary models of care, future research should focus on exploring, creating and testing pain care service approaches and methods, to determine those that fulfill the criteria of modern evidence-based practice, these principles being:1) the use of the best available research evidence,

2) clinical and business experience/expertise,

3) stakeholder/consumer preference and access to care and, importantly,

4) the available resources and funding.We strongly promote item 4 as an essential component of evidence-based practice, often omitted in care frameworks and practice guidelines. Research will continue to inform clinical practice by offering evidence from practice-based research that test packages or models of care for spinal pain, alongside assessment of teamwork and human dynamics encountered within service delivery.

These limitations of current care services for spinal pain are emphasized in a recently published Model of Care for Spinal Pain and WA Framework for Persistent Pain (2016– 2021), [26] where the case for patient-centered, coordinated and collaborative approach to care provision is offered. There are significant barriers to multidisciplinary, collaborative working, such as professional “turf wars,” limited incentive and problems with funding, but despite the difficulties, we believe that it can be performed and needs to be performed, for the benefit of patients and also to more efficiently manage the burden of chronic spinal pain on behalf of the health care system.

An example of how collaborative practice is emerging in Australia is via the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model, as described by Thistlethwaite [43] and Kellerman, [44] where health care practitioners are colocated and collaborate to improve care delivery in primary care, while reducing costs. This is not the only model of multidisciplinary working, and there are more than one way to skin the proverbial cat, but it does show the way health care practitioners, leadership, training and funding of care for chronic spinal pain, and other chronic diseases, will need to change, with the characteristics of good care being accessibility, quality care, safety, timely care and coordinated care. The complexity in chronic spinal pain management, as with other chronic conditions, is not only about the appropriate implementation of the individual parts of care but also ensuring that the triage, coordination of care and the multidisciplinary approach works well. This takes planning, commitment and leadership. For example, the colocation of health care practitioners in the same building does not guarantee multidisciplinary or integrated team care – there needs to be explicit consideration of human dynamics and the team process for teamwork to succeed. [45] Sound leadership provided by a champion of the service would facilitate this teamwork approach.

So, how can colocated health care teams be set up to deliver optimal care? We suggest that the process starts with motivated, energetic health care practitioners with an interest in chronic pain management to take the reins and begin planning for such community-based, primary care services. These motivated persons would draw upon their own practice experience and obtain advice/support from local health care organizations, such as Primary Health Networks [46] and the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative [47] encountered in Australia, among others, to develop a business case and feasibility of a local pain service.

Grants or funding for community-based pain services are vague with fluctuating commitment from government sources. Hence, community-based pain services are likely to develop through private funding or pain practitioners developing their own private practices that offer a broader range of services than currently offered. Also, organizations like the Primary Care Networks, or even private/corporate health care organizations, may be a source of funding or facilitation of pain services. We do, however, caution against getting caught up in health care politics, as witnessed with the UK Polyclinics [48, 49] and Australian Super Clinics [44, 50] which have received a mixed reception, where the attempt at integrating community-based care services has been negatively confounded by political influences.

In summary, we feel that there is already sufficient research evidence and recommendations documented in published guidelines, frameworks and models of care to inform clinical practice and the care of chronic spinal pain worldwide. The overt gap in care services is not the availability of prescription medication or allied health services, but rather the coordinated, multidisciplinary provision of care services by health care practitioners with an interest and skill in pain management. The challenge of our time is ensuring early access of patients with chronic spinal pain to care, coordinated practitioner teamwork and the application of the correct level of care individualized to the patient. On a positive note, this type of integrated service is emerging in dedicated pain centers and community-based clinics, which will hopefully expand going into the future. From here on, health care funders and medical insurers need to be persuaded that the model of care provision for chronic spinal pain is cost-efficient and cheaper than the current approaches. [8, 51]

Interventional pain procedures: Needles, probes, catheters or stimulation leads are used to pierce the skin and body parts, to reach a precise anatomical location to deliver drugs to the targeted areas or modulate nerve transmission, for the diagnosis or treatment of pain, either as a trial or a definitive procedure. This is usually in conjunction with imaging that allows confirmation of anatomically correct positioning of the needle, confirmation with radio-opaque contrast or fluid volume effect if using ultrasound.

Diagnostic interventional pain procedures: Diagnostic procedures require a precisely placed needle, through which local anesthetic (usually low volume) can be instilled in the anatomical structure, or over the anatomical path of the sensory nerve relevant to the proposed pain source that is being investigated. This is in conjunction with imaging that allows confirmation of anatomically correct positioning of the needle, confirmation with radio-opaque contrast or fluid volume effect if using ultrasound. This allows reproducibility if a significant reduction in pain is achieved during the local anesthetic phase. Placebo-controlled diagnostic blocks, or comparison between duration of local anesthetic action, require repeated procedures and are the gold standard. Diagnostic procedures aim to determine the relative contributions of anatomically linked pain as people can have multiple inputs from multiple structures. Co-instillation of corticosteroids and other adjuncts in some patients may prolong benefit, and in these instances the procedure can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Therapeutic interventional pain procedures: Needles, probes, catheters and/or stimulation leads are used to pierce the skin and body parts, to reach a precise anatomical location to deliver drugs to the targeted areas or modulate nerve transmission, with the expectation of pain relief for weeks, months or years. This is usually in conjunction with imaging that allows confirmation of anatomically correct positioning of the needle, confirmation with radio-opaque contrast or fluid volume effect if using ultrasound.

Acknowledgment

Gregory F Parkin-Smith and Stephanie J Davies were formerly the cochairs of Pain Health Working Group (Musculoskeletal Health Network of the WA Department of Health) and both were major contributors to the WA Framework for Persistent Pain.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References:

Briggs AM, Slater H, Bunzli S, et al.

Consumers’ experiences of back pain in rural Western Australia:

access to information and services, and self-management behaviours.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):357.Slater H, Briggs AM, Bunzli S, Davies SJ, Smith AJ, Quintner JL.

Engaging consumers living in remote areas of Western Australia in the self-management

of back pain: a prospective cohort study.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:69.Foster NE, Hill JC, O’Sullivan P, Hancock M.

Stratified models of care. Best practice & research.

Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27(5):649–661.Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Childs JD.

Subgrouping patients with low back pain: evolution of a classification approach

to physical therapy.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(6):290–302.Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, et al.

Comparison of Stratified Primary Care Management For Low Back Pain With

Current Best Practice (STarT Back): A Randomised Controlled Trial

Lancet. 2011 (Oct 29); 378 (9802): 1560–1571Foster NE, Mullis R, Hill JC, et al.

Effect of stratified care for low back pain in family practice (IMPaCT Back):

a prospective population-based sequential comparison.

Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):102–111.Adams J, Lauche R, Peng W, et al.

A workforce survey of Australian chiropractic:

the profile and practice features of a nationally representative sample of 2,005 chiropractors.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):14.Amorin-Woods LG, Parkin-Smith GF, Saboe V, Rosner AL

Recommendations to the Musculoskeletal Health Network, Health Department

of Western Australia related to the Spinal Pain Model of Care made on behalf

of the Chiropractors Association of Australia (Western Australian Branch)

Topics in Integrative Health Care 2014 (Jun 30); 5 (2)Cecchi F, Negrini S, Pasquini G, et al.

Predictors of Functional Outcome in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Undergoing Back School,

Individual Physiotherapy or Spinal Manipulation

Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012 (Sep); 48 (3): 371–378Deyo RA.

The role of spinal manipulation in the treatment of low back pain.

JAMA. 2017;317(14):1418–1419.Paige NM, Myiake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al.

Association of Spinal Manipulative Therapy with Clinical Benefit and Harm

for Acute Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

JAMA. 2017 (Apr 11); 317 (14): 1451–1460Garcia AN, Costa LdaCM, Hancock M, Costa LOP.

Identifying Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain Who Respond

Best to Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy: Secondary

Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial

Physical Therapy 2016 (May); 96 (5): 623–630Topp R, Swank AM, Quesada PM, Nyland J, Malkani A.

The effect of prehabilitation exercise on strength and functioning

after total knee arthroplasty.

PM R. 2009;1(8):729–735.Visser E, Davies S.

Expanding Melzack’s pain neuromatrix. The Threat Matrix: a super-system

for managing polymodal threats.

Pain Pract. 2010;10(2):163.Visser EJ, Ramachenderan J, Davies SJ, Parsons R.

Chronic widespread pain drawn on a body diagram is a screening tool for

increased pain sensitization, psycho-social load, and utilization of pain management strategies.

Pain Pract. 2016;16(1):31–37.Grace PM, Hutchinson MR, Maier SF, Watkins LR.

Pathological pain and the neuroimmune interface.

Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(4):217–231.Keppel Hesselink JM, Kopsky DJ.

Palmitoylethanolamide, a nutraceutical, in nerve compression syndromes:

efficacy and safety in sciatic pain and carpal tunnel syndrome.

J Pain Res. 2015;8:729–734.Canteri L, Petrosino S, Guida G.

Reducción del consumo de antiinflamatorios y analgésicos en el tratamiento del

dolor neuropático crónico en pacientes afectados por lumbociatialgia de tipo

compresivo y en tratamiento con Normast 300 mg

[Reduction in consumption of anti-inflammatory and analgesic medication in

the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain in patients affected by compression

lumbocischialgia due to the treatment with Normast 300 mg] (Spanish).

Dolor. 2010;25(4):227–234.Vallejo R, Tilley DM, Williams J, Labak S, Aliaga L, Benyamin RM.

Pulsed radiofrequency modulates pain regulatory gene expression

along the nociceptive pathway.

Pain Physician. 2013;16(5):E601–E613.Yeh CC, Sun HL, Huang CJ, et al.

Long-term anti-allodynic effect of immediate pulsed radiofrequency modulation

through down-regulation of insulin-like growth factor 2 in a neuropathic pain model.

Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(11):27156–27170.Wu B, Ni J, Zhang C, Fu P, Yue J, Yang L.

Changes in spinal cord met-enkephalin levels and mechanical threshold values

of pain after pulsed radio frequency in a spared nerve injury rat model.

Neurol Res. 2012;34(4):408–414.Yeh CC, Wu ZF, Chen JC, et al.

Association between extracellular signal-regulated kinase expression

and the anti-allodynic effect in rats with spared nerve injury by

applying immediate pulsed radiofrequency.

BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:92.NHMRC.

Evidence-Based Management of Acute Musculoskeletal Pain. 2003.

http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/cp94.pdf

Accessed May 11, 2015.Musculoskeletal Health Network.

Service Model for Community-Based Musculoskeletal Health in Western Australia.

Musculoskeletal Health Network; 2013. Available from:

http://www.healthnetworks.health.wa.gov.au/modelsofcare/docs/

Service_model_for_community-based_musculoskeletal_health_in_WA.pdf

Accessed November 1, 2016.Health Networks.

Spinal Pain Model of Care. 2009. Available from:

http://www.healthnetworks.health.wa.gov.au/modelsofcare/docs/

Spinal_Pain_Model_of_Care.pdf

Accessed May 11, 2015.WA Framework for Persistent Pain 2016–2021:

Improving the Health of People with Persistent Pain. 2016. Available from:

http://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/Articles/J_M/Musculoskeletal-Health-Network

Accessed March 2, 2017.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, et al.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review

for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 493–505Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al.

Systemic Pharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review

for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 480–492RACGP.

The RACGP Curriculum for Australian General Practice 2011:

Pain Management. 2011. Available from:

http://curriculum.racgp.org.au/media/12341/painmanagement.pdf

Accessed November 1, 2016.Speerin R, Slater H, Li L, et al.

Moving from evidence to practice: models of care for the prevention

and management of musculoskeletal conditions.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(3):479–515.Briggs AM, Towler SC, Speerin R, March LM.

Models of care for musculoskeletal health in Australia:

now more than ever to drive evidence into health policy and practice.

Aust Health Rev. 2014;38(4):401–405.Amorin-Woods LG, Beck RW, Parkin-Smith GF, Lougheed J, Bremner AP.

Adherence to Clinical Practice Guidelines Among Three Primary

Contact Professions: A Best Evidence Synthesis of the Literature

for the Management of Acute and Subacute Low Back Pain

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2014 (Sept); 58(3): 220–237Naccarella L, Greenstock LN, Brooks PM.

A framework to support team-based models of primary care within the

Australian health care system.

MJA Open. 2012;1(suppl 3). Available from:

hthttps://www.mja.com.au/system/files/issues/001_03_230712/nac10069_fm.pdf

Accessed November 1, 2016.Hogg MN, Gibson S, Helou A, DeGabriele J, Farrell MJ.

Waiting n pain: a systematic investigation into the provision of persistent

pain services in Australia.

Med J Aust. 2012;196(6): 86–390.Roxburgh A, Burns L [webpage on the Internet].

Accidental Drug-Induced Deaths Due to Opioids in Australia, 2008. 2012.

http://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/resource/accidental-opioid-induceddeaths-australia-2008

Accessed August 20, 2015.Britt H, Charles J, Henderson J, et al.

Table 6.3: Distribution of patient reasons for encounter, by ICPC-2 chapter

and most frequent individual \reasons for encounter within chapter.

General Practice Activity in Australia 2007–08.

Sydney: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2008:39–40.Upshur C, Luckmann R, Savageau J.

Primary care provider concerns about management of chronic pain in

community clinic populations.

J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:652–655.Wan A.

GP pain management: what are the ‘Ps’ and ‘As’ of pain management?

Aust Fam Physician. 2014;43(8):537.Goucke C.

The management of persistent pain.

Med J Aust. 2003;178: 444–447.O’Rorke JE, Chen I, Genao I, Panda M, Cykert S.

Physicians’ comfort in caring for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain.

Am J Med Sci. 2007;333(2):93–100.Hamilton C.

The third way and the end of politics.

Draw Board Austr Rev Public Aff. 2001;2(2):90–102.Bobbio N.

Left and Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction/Destra e Sinistra:

Ragioni e significati di una distinzione politica.

Chicago, Cambridge, United Kingdom:

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Polity Press; 1997:8.Thistlethwaite JE.

The medical home: a need for collaborative practice.

Aust Fam Physician. 2016;45(10):759.Kellerman R.

The patient centred medical home: a new model of practice in the USA.

Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38(5):279.Hepworth J, Marley J.

Healthcare teams – a practical framework for integration.

Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(12):969–971.PHCRIS [webpage on the Internet].

Introduction to Primary Health Networks (PHNs). 2016. Available from:

http://www.phcris.org.au/guides/intro_phns.php

Accessed November 1, 2016.Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC)

[webpage on the Internet]. 2016. Available from:

https://www.pcpcc.org/about

Accessed November 1, 2016.Higson N.

What is and what is not a polyclinic.

BMJ. 2008;336(7654): 1145.Kay S.

Will polyclinics deliver real benefits for patients? No.

BMJ. 2008; 336(7654):1165.Bonney A, Farmer EA.

Health care reform: can we maintain personal continuity?

Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(7):455.Maeng DD, Graboski A, Allison PL, Fisher DY, Bulger JB.

Impact of a value-based insurance design for physical therapy to treat back pain

on care utilization and cost.

J Pain Res. 2017;10:1337

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Since 9-12-2017

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |