Patient-reported Improvements of Pain, Disability, and Health-related

Quality of Life Following Chiropractic Care for Back Pain -

A National Observational Study in SwedenThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2019 (Apr); 23 (2): 241–246 ~ FULL TEXT

Gedin F, MSc; Dansk V, MSc; Egmar A-C, PhD; Sundberg T, PhD; Burström K, PhD

Health Economics and Economic Evaluation Research Group,

Medical Management Centre,

Karolinska Institutet,

Stockholm, Sweden

BACKGROUND: Chiropractic care is a common but not often investigated treatment option for back pain in Sweden. The aim of this study was to explore patient-reported outcomes (PRO) for patients with back pain seeking chiropractic care in Sweden.

METHODS: Prospective observational study. Patients 18 years and older, with non-specific back pain of any duration, seeking care at 23 chiropractic clinics throughout Sweden were invited to answer PRO questionnaires at baseline with the main follow-up after four weeks targeting the following outcomes: Numerical Rating Scale for back pain intensity (NRS), Oswestry Disability Index for back pain disability (ODI), health-related quality of life (EQ-5D index) and a visual analogue scale for self-rated health (EQ VAS).

RESULTS: 246 back pain patients answered baseline questionnaires and 138 (56%) completed follow-up after four weeks. Statistically significant improvements over the four weeks were reported for all PRO by acute back pain patients (n = 81), mean change scores: NRS -2.98 (p < 0.001), ODI -13.58 (p < 0.001), EQ VAS 9.63 (p < 0.001), EQ-5D index 0.22 (p < 0.001); and for three out of four PRO for patients with chronic back pain (n = 57), mean change scores: NRS -0.90 (p = 0.002), ODI -2.88 (p = 0.010), EQ VAS 3.77 (p = 0.164), EQ-5D index 0.04 (p = 0.022).

There are more articles like this @ our:

SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT PageCONCLUSIONS: Patients with acute and chronic back pain reported statistically significant improvements in patient-reported outcomes (PRO) four weeks after initiated chiropractic care. Albeit the observational study design limits causal inference, the relatively rapid improvements of PRO scores warrant further clinical investigations.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

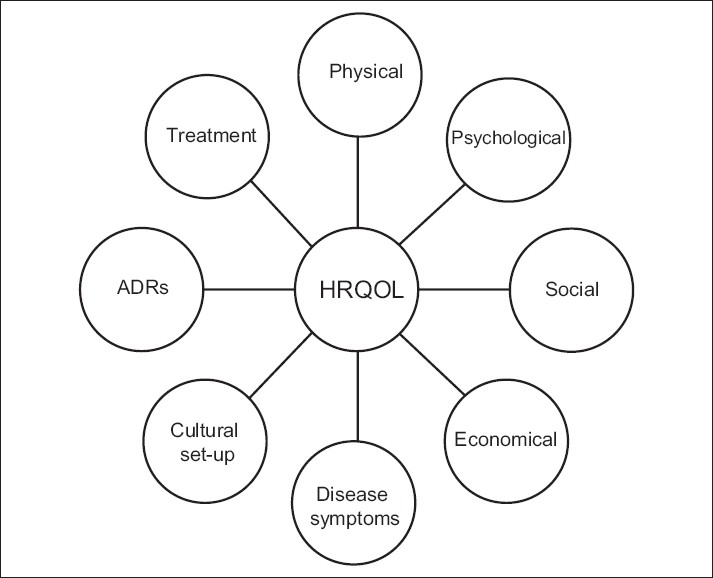

Back pain is a common disorder that affects both physical health and mental wellbeing (Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering, 2000). In addition to the individual suffering back pain also has significant impact on societal costs (Lidwall, 2011; Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering, 2000). Back pain is a complex condition that may be caused by a variety of biological, psychological and social factors (Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering, 2010; van Tulder et al, 2006). It has been estimated that the vast majority of back pain cases is of non-specific origin (Airaksinen et al, 2006; van Tulder et al, 2006), which can make it especially difficult to manage efficiently. Chiropractic treatment such as spinal manipulation is recommended in clinical guidelines of back pain management (Globe et al, 2016; Lidwall, 2011; van Tulder et al, 2006), especially so in the care of nonspecific back pain. Recent research also reports emerging evidence that chiropractic care is a safe treatment for low back pain with clinically effects similar to physical therapy, and likely similar to exercise and medical care, albeit the cost-effectiveness of chiropractic care for low back pain is still uncertain (Blanchette et al, 2016), as is the impact on wellbeing outcomes that are often associated with chiropractic care (Parkinson et al, 2013). Notably, patient-reported outcomes (PRO), i.e. outcomes that details different aspects of patients' health status that by means of patient report, e.g. health-related quality of life (HRQoL), has been suggested as an important area of research to increase the understanding and improvement of clinical care (Deshpande et al, 2011).

Chiropractors in Sweden become qualified to practice after five years of training at the Scandinavian College of Chiropractic in Sweden or at an equivalent educational institution abroad. All Swedish chiropractors need to be registered by the National Board of Health and Welfare. In Sweden, chiropractic is a registered health care profession alongside physiotherapy, medicine and other health professions, and chiropractors have to follow the health care regulations set by the Swedish health care authorities. Any misconduct in chiropractic practice has to be reported to the Health and Social Care Inspectorate. The majority of Swedish chiropractors work in private practice outside of conventional medical settings such as general practitioners offices or hospitals. Nonetheless, Swedish county councils recommend chiropractic care alongside other manual therapy interventions and physiotherapy for patients with back pain and other musculoskeletal disorders (Vårdguiden, 2017). However, despite the increased acceptance of chiropractic care in Sweden there is a scarcity of studies investigating chiropractic practice in Sweden. The aim of the present study was to explore PRO targeting back pain, back disability and health related quality of life (HRQoL) for patients with low back pain seeking chiropractic care in Sweden.

Discussion

This study explored PRO, i.e. back pain intensity, back disability, health-related quality of life and self-rated health, among patients with back pain receiving chiropractic care in Sweden. Patients with acute back pain reported statistically significant improvements between baseline and the main follow-up after four weeks for all PRO. Patients with chronic back pain also reported statistically significant, albeit somewhat smaller, improvements after four weeks for all PRO, except for self-rated health.

The rapid improvement of back pain intensity after two weeks for acute back pain patients could suggest a chiropractic treatment effect, which would be in line with previous studies indicating that chiropractic care may improve pain and disability in short term (Goertz et al, 2013; Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering, 2010; Walker et al, 2010). However, it has been suggested that 90% of patients with acute low back pain recover within six weeks (van Tulder et al, 2006), which may also help explain the current findings of rapid improvements. The observed improvement of pain intensity was of MCID and maintained over the study period for acute back pain patients. Nonetheless, the observational study design and lack of control group makes it impossible to distinguish potential chiropractic treatment effects on pain reduction from the natural progression of back pain. It may further be assumed that patients with acute back pain might naturally improve more in contrast to patients with chronic back pain. The most recent Swedish health technology assessment report (Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering, 2016), which addresses the knowledge gap of the effectiveness of manipulative therapies in the management of acute and sub-acute low back pain, requests more clinical research of available treatments in this area. Accordingly, the current study's PRO findings of acute back pain patients receiving chiropractic care might contribute towards generating hypotheses and informing larger scale clinical studies in this requested area of research.

The back disability ODI values reported at baseline among patients with acute pain in this study were similar to what patients in the general population with acute back pain report (Rabin & de Charro, 2001). The ODI results in this study also followed the same pattern as the EQ-5Dindex, where patients with acute pain reported similar disability/function after four weeks as the general population without disability/function (Rabin & de Charro, 2001). This could be an indication that patients with acute pain recovered at the end of study, but should be interpreted carefully as the characteristics of the study populations may differ.

The baseline EQ-5Dindex for patients seeking chiropractic care was similar to general Swedish population estimates for people with back pain (Burström et al, 2001b). This suggests that the health status of patients seeking chiropractic care does not differ substantially from the patients with back pain in the general population. Pain/discomfort was the EQ-5D dimension where most patients reported problems at baseline, followed by usual activities and mobility. Self-care was the EQ-5D dimension where fewest patients reported problems. This is similarly shown in the general population in Stockholm where pain/discomfort is also among the main reported problems, whereas self-care is the least (Burström et al, 2001a). After the last follow-up at four weeks, patients who received chiropractic care for acute back pain reported similar EQ-5Dindex after two and four weeks as the general Swedish population without pain (Burström et al, 2001b). This improvement suggests a normalization of back pain over time that may have been related to the chiropractic care although it is possible that the same rapid improvements could have occurred due to the natural history of back pain. Even so, the current study adds new knowledge with details about changes in EQ-5D health status for patients seeking chiropractic care. Similarly, and in line with the reported positive improvements of health status following chiropractic care, a recent US study suggests that the majority of chiropractic users report that chiropractic helps to improve their overall health or wellbeing (Adams et al, 2017).

There are multiple previously reported clinical studies on chiropractic. However, these are typically based on chiropractic practice in the US and English speaking countries, and there is a scarcity of studies that describe routine chiropractic care in Sweden. Thus relevantly, this study adds to the literature by describing and contextualising standard PRO of patients receiving chiropractic care in Sweden. This may be of value since chiropractic can be considered a marginalised, albeit regulated and licensed, health profession in Sweden, e.g. considering that chiropractic is mainly taught outside of medical universities and that the vast majority of Swedish chiropractors work in private practice outside of conventional medical settings. Building on the current observational study, future studies may want to investigate the comparative effectiveness of chiropractic care versus treatment as usual, as well as barriers and facilitators of integrating chiropractic and conventional care, for the target group of patients with non-specific low back pain. Future studies addressing chronic back pain groups might also want to consider longer follow-up periods (Lidwall, 2011).

Methodological considerations

Strengths of the current study include that the chiropractic clinics were geographically distributed all over Sweden, of varying size, some having conventional care contracts, and that the chiropractors at each clinic had different lengths of working experience, which may aid to the study's representativeness of general chiropractic practice. Study limitations include the observational single arm study design which limits causal relations between observed outcomes changes and chiropractic care, the convenience sampling of patients and the non-randomized inclusion of chiropractic clinics which may have caused selection bias where the most “ambitious” or appropriate clinics or patients chose to participate (Machin & Campbell, 2005).

Additionally, the lack of specific data on the type and content of administered chiropractic treatments, such as which exact techniques were utilized, and the fairly large number of drop-outs, which had significantly more young patients and manual workers than the responders remaining in the study, are limitations that ought to be considered when interpreting the results of this study and when planning for future investigations. The short follow-up period of four weeks, and the lack of references detailing scientifically validated translations of the implemented instruments into Swedish, constitute additional aspects that might be considered in future studies. The findings may not be generalizable to the general population with back pain, as patients seeking chiropractic care might differ in characteristics from those who do not.

Conclusions

Patients with acute back pain reported statistically significant and minimal clinically important difference (MCID) improvements in back pain intensity, back disability and health related quality of life (HRQoL), and statistically significant improvements in self-rated health, over four weeks following chiropractic care. Patients with chronic back pain reported statistically significant, albeit smaller and non MCID, changes for all patient-reported outcomes (PRO) except self-rated health. The observed improvements in PRO may be of interest for clinicians and decision makers involved in the management of back pain patients. The study findings may additionally contribute to inform future research in the field of chiropractic care and back pain.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Mesfin Tessma for technical support and the staff at the Scandinavian College of Chiropractic for logistical support during the study. Kiropraktiska Föreningen i Sverige provided financial support towards the administrative costs making it possible to conduct this study, but did not have any influence on any part of the research process of this study. The authors declare no other source of funding or conflicts of interest for this study.

References:

Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, et al.

The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults:

Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017 (Dec 1); 42 (23): 1810–1816Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al.

COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain Chapter 4.

European Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain

European Spine Journal 2006 (Mar); 15 Suppl 2: S192–300Blanchette M, Stochkendahl M., Da Silva RB, et al.

Effectiveness and Economic Evaluation of Chiropractic Care for the Treatment of

Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review of Pragmatic Studies

PLoS One. 2016 (Aug 3); 11 (8): e0160037Boynton PM 2004

Administering, analysing, and reporting your questionnaire.

Bmj 328: 1372-1375.Burström K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F 2001a

Health-related quality of life by disease and socio-economic group in the general population in Sweden.

Health policy 55: 51-69.Burström K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F 2001b

Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D.

Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation 10: 621-635.Chapman JR, Norvell DC, Hermsmeyer JT, Bransford RJ, DeVine J, McGirt MJ, Lee MJ 2011

Evaluating common outcomes for measuring treatment success for chronic low back pain.

Spine, United States, pp. S54-68.Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, Rosenquist RW, Atlas SJ, Baisden J, et al.

Interventional Therapies, Surgery, and Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation for Low Back Pain:

An Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline From the American Pain Society

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009 (May 1); 34 (10): 1066–1077Davidson M, Keating JL (2002)

A Comparison of Five Low Back Disability Questionnaires: Reliability and Responsiveness

Physical Therapy 2002 (Jan); 82 (1): 8–24Deshpande PR, Rajan S, Sudeepthi BL, Abdul Nazir CP 2011

Patient-reported outcomes: A new era in clinical research.

Perspectives in clinical research 2: 137-144.Dolan P 1997

Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states.

Medical care 35: 1095-1108.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O'Brien BJ, Stoddart GL 2005

Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes.

Oxford University Press, USAFairbank JC, Pynsent PB 2000

The Oswestry Disability Index

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000 (Nov 15); 25 (22): 2940–2952Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole MR.

Clinical Importance of Changes in Chronic Pain Intensity

Measured on an 11-point Numerical Pain Rating Scale

Pain 2001 (Nov); 94 (2): 149-158Globe, G, Farabaugh, RJ, Hawk, C et al.

Clinical Practice Guideline:

Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 1–22Goertz CM, Long CR, Hondras MA, Petri R, Delgado R, Lawrence DJ, et al.

Adding Chiropractic Manipulative Therapy to Standard Medical Care

for Patients with Acute Low Back Pain: Results of a Pragmatic

Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 (Apr 15); 38 (8): 627–634IBM Corp 2012

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0.

IBM Corp, Armonk.Jansson KA, Nemeth G, Granath F, Jonsson B, Blomqvist P 2009

Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) before and one year after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis.

The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume 91: 210-216.Kane RL, Radosevich DM 2010

Conducting Health Outcomes Research.

Jones & Bartlett LearningKiropraktiska Föreningen i Sverige 2017 Ett patientbesök - KFS.

Kiropraktiska Föreningen i Sverige.Lidwall U 2011 Vad kostar olika sjukdomar i sjukförsäkringen?

Kostnader för sjukpenning i sjukskrivningar (över 14 dagar) samt sjukersättning och aktivitetsersättning

år 2009 fördelat på diagnos. Försäkringskassan.Machin D, Campbell MJ 2005

The Design of Studies for Medical Research.

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, West SussexMonticone M, Baiardi P, Vanti C, Ferrari S, Pillastrini P, Mugnai R, Foti C 2012

Responsiveness of the Oswestry Disability Index and the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire in

Italian subjects with sub-acute and chronic low back pain.

European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society 21: 122-129.Parkinson L, Sibbritt D, Bolton P, van Rotterdam J, Villadsen I 2013

Well-being outcomes of chiropractic intervention for lower back pain: a systematic review.

Clinical rheumatology 32: 167-180.Pool JJ, Ostelo RW, Hoving JL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC 2007

Minimal clinically important change of the Neck Disability Index and the Numerical Rating Scale for patients with neck pain.

Spine, United States, pp. 3047-3051.Rabin R, de Charro F 2001

EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group.

Annals of medicine 33: 337-343.Solberg TK, Olsen JA, Ingebrigtsen T, Hofoss D, Nygaard OP 2005

Health-related quality of life assessment by the EuroQol-5D can provide cost-utility data

in the field of low-back surgery.

European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society,

the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the

Cervical Spine Research Society 14: 1000-1007.Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering 2016

Preventiva insatser vid akut smärta från rygg och nacke. Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering,

StockholmStatens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering 2000

Ont i ryggen, ont i nacken.

Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering, Stockholm.Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering 2010

Rehabilitering vid långvarig smärta. Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering,

Stockholm.Svensk Ryggkirurgisk Förening 2017

Diagnosrelaterad information, Svenska Ryggregistret

SweSpine.Walker BF, French SD, Grant W, Green S 2010

Combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain.

Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online): CD005427.van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, Breen A, Carter T, Gil del Real MT.

European Guidelines for the Management of Acute Nonspecific Low Back Pain in Primary Care

European Spine Journal 2006 (Mar); 15 Suppl 2: S169–191Whynes DK, McCahon RA, Ravenscroft A, Hodgkinson V, Evley R, Hardman JG 2013

Responsiveness of the EQ-5D health-related quality-of-life instrument in assessing low back pain.

Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 16: 124-132.Vianin M 2008

Psychometric properties and clinical usefulness of the Oswestry Disability Index.

J Chiropr Med, United States, pp. 161-163.Williamson A, Hoggart B 2005

Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales.

Journal of clinical nursing 14: 798-804.Vårdguiden 2017

Kiropraktik och naprapati - 1177 Vårdguiden - sjukdomar, undersökningar, hitta vård, e-tjänster.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Since 5-20-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |