Best-Practice Recommendations for Chiropractic Care

for Pregnant and Postpartum Patients:

Results of a Consensus ProcessThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2021 (Nov 23); S0161-4754(21)00036-1 ~ FULL TEXT

Carol Ann Weis, MSc, DC • Katherine Pohlman, DC, PhD • Jon Barrett, MBBch, MD

Maeve O'Beirne, MD, PhD • Kent Stuber, DC, MSc • Cheryl Hawk, DC, PhD

Department of Research,

Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College,

Toronto, ON, Canada.

Objective: The purpose of this project was to develop a best-practices document on chiropractic care for pregnant and postpartum patients with low back pain (LBP), pelvic girdle pain (PGP), or a combination.

Methods: A modified Delphi consensus process was conducted. A multidisciplinary steering committee of 11 health care professionals developed 71 seed statements based on their clinical experience and relevant literature. A total of 78 panelists from 7 countries were asked to rate the recommendations (70 chiropractors and representatives from 4 other health professions). Consensus was reached when at least 80% of the panelists deemed the statement to be appropriate along with a median response of at least 7 on a 9-point scale.

Results: Consensus was reached on 71 statements after 3 rounds of distribution. Statements included informed consent and risks, multidisciplinary care, key components regarding LBP during pregnancy, PGP during pregnancy and combined pain during pregnancy, as well as key components regarding postpartum LBP, PGP, and combined pain. Examination, diagnostic imaging, interventions, and lifestyle factors statements are included.

Conclusion: An expert panel convened to develop the first best-practice consensus document on chiropractic care for pregnant and postpartum patients with LBP or PGP. The document consists of 71 statements on chiropractic care for pregnant and postpartum patients with LBP and PGP.

Keywords: Chiropractic; Low Back Pain; Pelvic Girdle Pain; Postpartum; Pregnancy; Spine.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

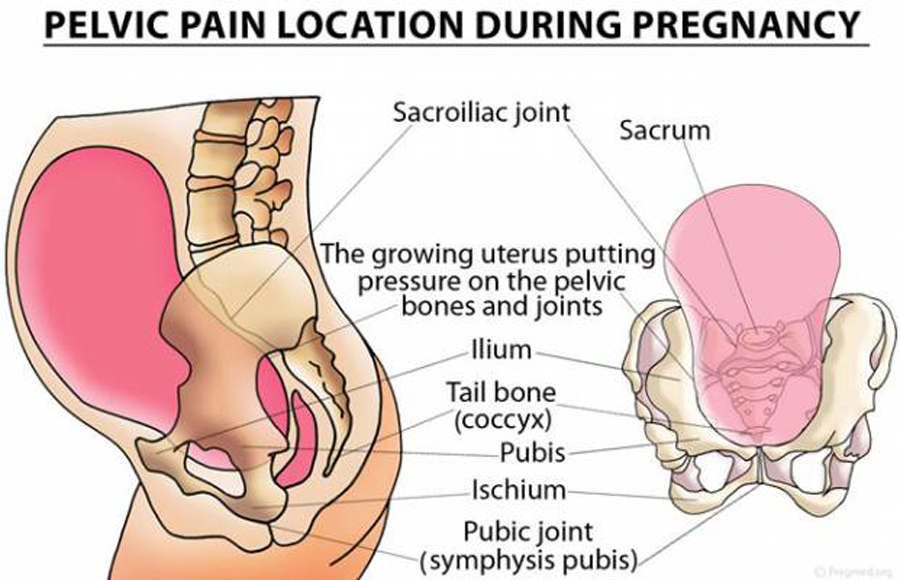

In the general population, low back pain (LBP) is a primary cause of years lived with disability and is the sixth in overall disability-adjusted life-years. [1, 2] Pregnancy-related back pain is experienced by up to 90% of pregnant women [3–7] with up to 35% of them classifying their pain as moderate, severe, or disabling, [4, 5, 7, 8–10] affecting their activities of daily living. [4, 5, 11] Approximately 30% of women report their first bout of back pain during pregnancy, and although the pain often resolves spontaneously after birth, up to 75% of women may continue to experience pain up to 3 years postpartum. [12–14] Women who experienced postpartum-related back pain at 3 months were at higher risk for chronic LBP throughout their lives. [15, 16] Previous studies also suggests that women experiencing LBP and pelvic girdle pain (PGP) are actually experiencing different conditions [5, 7, 17–21]; however these pains are often studied as the same condition. While LBP is defined as pain between the costal margins and the inferior gluteal folds, [18, 22, 23] PGP is defined as pain in the symphysis pubis and/or between the posterior iliac crest and gluteal folds. [18, 22–24] When LBP and PGP occur simultaneously [22–24] this should be referred to as “combination” or “combined” pain.

The lack of a consistent definition for back pain experienced during pregnancy and postpartum periods makes the determination of etiology, pathophysiology, and risk factors for these conditions very heterogeneous. [16, 22, 23, 25–27] As a result, determining safe and effective management strategies for these patients is very challenging. [16, 22, 23, 28] Additionally, pregnancy-related back pain often resolves after delivery and does not pose known serious risks to the mother or fetus [17, 29]; many health care providers dismiss these complaints [4, 5, 17] as a temporary and self-limiting condition. [17] This leaves women with pregnancy-related back pain with little or no recommendations for treatment. [4, 9] Similarly, women with postpartum-related back pain rarely seek health care services [30] and those who do often have their pain minimalized by their health care provider, who is usually unable to provide them with treatment or even information on their condition. [30–32]

Chiropractors have special training in diagnosis and management of musculoskeletal conditions. [33–35] Effective chiropractic care has been suggested to consist of a “package of conservative approaches” [36] or “multimodal treatment” [37] that is consistent with clinical practice guidelines or available best-practice papers. Similar to other disciplines (ie, Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, and naturopathic medicine), the research that has been completed has been focused on a modality (eg, acupuncture, spinal manipulation therapy) versus the entire discipline. [38] Most individual modalities within the scope of a profession are not intended to be used in isolation, though it is easier to conduct research on an individual modality where a protocol can be defined and applied consistently across all patients in a study. Recent guidelines recommend that programs of chiropractic care should include patient education and advice, and supervised and home exercises in addition to manual therapy (including spinal manipulative therapy [SMT] and mobilizations). [37, 39–43] Spinal manipulation and mobilization are typically hands-on treatment of the spine, and may include a high-velocity impulse or thrust applied to a synovial joint over a short amplitude at or near the end of the passive or physiological range of motion or a low grade velocity, small- or large-amplitude passive movement techniques within the patient's range of motion and control, respectively. In the general population, SMT has been used as a treatment to decrease pain and improve disability for spinal pain and headaches. [37, 44–47] Regarding safety and SMT, severe adverse effects are rare. [48–51] In fact, most reported adverse events are minor and transient (such as muscle soreness) and resolve within 24 hours after SMT. [52, 53]

Chiropractic care is a viable health care option for pregnant and postpartum patients with back pain. [54–58] Chiropractors have reported safe and successful treatment of pregnancy- and postpartum-related back pain. [57, 59] Consequently, health care providers are willing to recommend complementary and alternative medicine, such as chiropractic care, for their patients who may be experiencing pregnancy- and postpartum-related back pain. [33, 35] Additionally, women experiencing pregnancy- and postpartum-related back pain frequently pursue non-drug alternatives to alleviate their pains. [31, 32, 60] Despite the strong evidence for successful musculoskeletal care in the general adult population and an ever-increasing body of literature that supports chiropractic care for pregnant and postpartum patients, there are still important gaps in the literature, such as the best ways to prevent pain and manage these patients. [30–32, 57] Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop best-practice recommendations based on evidence for chiropractic care of pregnant and postpartum patients with LBP, PGP, or combined pain by conducting a consensus process using a multidisciplinary group of pregnancy and postpartum care experts.

Methods

Study Overview

Because there is insufficient evidence on chiropractic care for the pregnancy and postpartum periods, it was determined that a full clinical practice guideline would not be possible. Best-practice documents can bridge the practice-research gap and have been successfully developed in other topic areas. [36, 52, 61–63] By definition:Best practice is not a specific practice per se but rather a level of agreement about research-based knowledge and an integrative process of embedding this knowledge into the organization and delivery of health care. Best practice requires a level of agreement about evidence to be integrated into practice. Best practice can bridge the practice-research gap and provide a basis for researchers and clinicians to work together to translate research into meaningful practice. [64]

Like other best-practice articles, [36, 52] we aimed to outline the features of chiropractic care based on best available evidence and expert clinical experience that represent the most beneficial approach to chiropractic care for the pregnant and postpartum populations. We included manual therapies, adjunctive modalities, and physical agents that chiropractors may use in the management of pregnant and postpartum patients but do not require additional certifications. In this project, manual therapy included SMT, mobilization, soft tissue therapy and instrument-assisted soft tissue therapy.

Human Participant Considerations

This project was approved by the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College Research Ethics Board (1903 × 01). Electronic informed consent was obtained from panelists with all responses still being voluntary.

Composition of the Steering Committee

Table 1 Table 1 summarizes the professions and experience represented in the steering committee (SC), which was ensured to be composed of nationally recognized experts who work extensively with pregnant and postpartum populations and a research project manager. Three different health professions were represented: chiropractic, medicine, and physiotherapy. Within medicine there was an obstetrician, a family medicine practitioner, and a physical medicine and rehabilitation practitioner. As with other best-practice articles in chiropractic care, [36, 52] these members were selected to provide insight into the recommendations and ensure that all health care provider stakeholders’ perspectives were included.

Literature Review and Initial Seed Document

The development of the seed statements started with the identification of the different topic areas by the study team. These included informed consent and risk; history and physical exam for LBP, PGP, and combined pain; risk factors; and interventions. Seed statements for each area were developed by the lead author (C.A.W.) to present to the attendees of a workshop at a chiropractic conference in spring 2017, including both clinicians and scientists. The workshop attendees reviewed the initial seed statements, where study team members acted as a facilitator for the smaller group's discussion. Attendees (n = 31) provided feedback on the initial seed statements and were invited to partake as panelists for the formal consensus process.

After the workshop, 2 systematic reviews for chiropractic care in pregnant and postpartum populations were completed by 6 members of the SC (C.D., S.D.O., C.H., K.P., K.S., C.A.W.). [65, 66] Seed statements were further developed and enhanced based on these reviews.

These statements were reviewed by the members of the SC for comprehension, completeness, and relevance for chiropractic practice. After modifications, all SC members were asked to review the seed statements again before they were sent to the panelists. The seed statement document that was used to start the consensus process consisted of 71 statements.

Composition of the Panel

The panel was composed of attendees at an international chiropractic conference, nomination by the SC, and by invitations sent to relevant organizations. A workshop was delivered in spring 2017. There were no specific criteria for selection of attendees to the workshop, as we did not know ahead of time who would be attending the conference. The contact information for those who attended was kept and attendees were then re-contacted once the modified Delphi process was to begin to determine participation. In addition, the SC was asked to nominate panelists and invitations were sent to relevant organizations, including American Physical Therapy Association, National Association of Certified Professional Midwives, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’, Midwives Alliance of North America, Canadian Chiropractic Association, and The Clinical Compass. All volunteer panelists (n = 131) completed a form describing their demographic information. The principal investigator and project manager selected panelists based on their experience and diversity of geography, demographics, and profession. An emphasis was placed on identifying pre- and postnatal care experts from outside the chiropractic profession, as well as doctors of chiropractic (DCs) with dual degrees.

Modified Delphi Process

The consensus process was conducted electronically via email. We followed a modified version of the RAND-UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) methodology for conducting the Delphi process. [67]

The panelists were provided with seed statements and all citations and were sent full text for any reference upon request. For each statement, panelists were asked to rate its appropriateness. The term “appropriateness” was used to indicate that the expect health benefit to the patient exceeds the expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin, suggesting that it is worth doing, exclusive of cost. [67] The rating scale ranged from 1 (highly inappropriate) to 9 (highly appropriate). In analyzing the responses, we categorized the ratings of 1 to 3 as “inappropriate,” 4 to 6 as “undecided,” and 7 to 9 as “appropriate.”

If the panelists indicated a procedure or practice as inappropriate (1-3), they were asked to state reasons and references. If no reason was provided, their responses were considered incomplete and recorded as missing. The “inappropriate” ratings with provided reasons were reviewed by the SC used to revise the statement. A seed statement reached consensus if at least 80% of panelists rated a given statement as 7, 8, or 9 and the median response score was between 7 and 9.

The initial 71 seed statements were sent to panelists in 2 parts: statements 1 to 35 and statements 36 to 71. Seed statements 1 to 35 were sent June 2019 and seed statements 36 to 71 were sent July 2019. Panelists were given 2 weeks after the initial 2 emails to return the seed statements with any suggested revisions or feedback. Seed statements from this initial review that did not reach consensus were revised as per the panelists’ rationale and sent to the SC to review and approve. Panelists were sent all revised statements. This process was repeated until consensus was reached for all statements. Once consensus was reached by the panelists, the final statements were sent to the SC for final review and approval.

Results

Characteristics of the Panelists

Seventy-eight people (63 women and 15 men) were invited and consented to be panelists. Ten of the 23 panelists who attended the 2017 conference workshop agreed to participate, and all others were either nominated or responded to the invitation sent to the professional organizations.

Panelists included70 DCs,

5 physical therapist (PT),

1 family doctor of medicine (MD),

1 midwife (MW) and

1 MD obstetrician-gynecologist (OB/GYN).Twelve DCs, 3 PTs, 1 MD, 1 MW, and 1 OB/GYN are faculty members of programs within their respective professions. One panelist had a dual degree (DC/registered massage therapist), 2 panelists had PhDs, and 9 had master's degrees in addition to their professional degrees.

Panelists represented 7 countries:Canada (n = 40),

the United States (n = 31),

United Kingdom (n = 2),

Australia (n = 2),

The Netherlands (n = 1) and

Sweden (n = 1).For advanced training in pre- and postnatal care, 8 DC panelists reported being certified in Webster technique and 4 PT panelists reported extra pregnancy/postnatal training and/or certification. The panelists have been in practice a median of 15 years (range: 5-40 years), and the median estimate for proportion of pregnant and postpartum patients was 10% (range: 0.5%-50%) and 15% (range: 0.5%-77%), respectively.

Panelist Responses

Figure 1 The process was conducted from June to November 2019. As shown in Figure 1 and Tables 2 and 3 (NOTE: For Table 2 + 3, please review them online), consensus was reached on all statements after 3 rounds. After the initial email, which included statements 1 to 35, 1 panelist withdrew their consent of participation (for personal reasons) and 5 panelists failed to respond, resulting in a total of 71 responses. After the second email, which included statements 36 to 71, 8 panelists failed to respond, resulting in 68 responses. Consensus was reached on 61 statements after these initial emails (Table 2). One seed statement (seed statement 63) that did not meet consensus was missed when compiling the results from the original 71 statements and was not included in the subsequent rounds. However, with revisions to other statements all relevant information from this statement was captured. Therefore, the second round consisted of 9 statements that did not reach consensus (statements 3, 8, 34, 35, 46, 50, 52, 62, and 65), which were sent to panelists 4 weeks after the first round consensus was reached on 6 of the statements, based on a total number of 64 responses (Table 3). In the final round, the 3 statements that had yet to meet consensus (statements 35, 50, and 62) were distributed, and consensus was reached based on a total number of 63 responses (Table 3). This process resulted in the following statements.

Best Practices for Pregnant and Postpartum Women With LBP, PGP, or Combined Pain

The purpose of this best practice document is to define the parameters of an appropriate approach to chiropractic care for pregnant and postpartum women with LBP, PGP, or combined pain (defined within the document). As such, some of the seed statements are general in nature (such as informed consent and risks) and can apply to all pregnant women. Other statements are specific to the time of parturition and/or type of back pain experienced, as they commonly have different parameters (such as pain presentation, risk factors, and physical exam). Because chiropractic care differs from region to region, not all statements may be pertinent and should be interpreted within the scope of practice and laws of regional regulators.

Informed Consent & Risks

Statement 1: Informed Consent

Informed consent is an ever-evolving dynamic process [68] that should be updated with the unique changes occurring from pregnancy to postpartum conditions. As such, clinicians should discuss the benefits of the treatment, the treatment itself, expected outcomes, material risks, and side effects of the proposed examination and management plan. [68, 69] Furthermore, a discussion involving the rare but potentially serious risks, correlated with various physical and manual therapies inherent within chiropractic care, should be included. As these patients’ health status is ever changing (ie, from 2 months pregnant to 9 months pregnant to postpartum), these discussions should be ongoing and documented so that issues such as ligament laxity and biomechanical changes can be considered as they change over the course of the pregnancy and into the postpartum period.

Statement 2: Adverse Events

Mild and transient side effects have been reported after lumbar spine SMT and, although rare, serious adverse events have been reported following cervical SMT in a few case reports. [70, 71] If red flags are identified during pregnancy and early postpartum, clinicians should fully discuss the risks of SMT in each of the spinal regions they are considering adjusting. [70, 72]

Statement 3: Informed Consent

A thorough history and physical examination may help to identify potential red flags such as prothrombotic and extreme joint laxity. [70] The clinician should discuss with their patient the selected procedures in the recommended treatment plan and any potential concerns and to ensure informed consent (verbal and written) has been obtained. This may include providing the patient with various treatment options including mobilization, low-force techniques, or other types of adjustments. [73]

Statement 4: Possible Modifications

Spinal manipulation is considered a safe and effective form of conservative therapy that has been shown to provide relief for patients with mechanical back pain. Clinicians should also consider instances in which SMT should be modified or may not be warranted. [70, 74] Modifications or alternate chiropractic procedures should be considered and offered in these cases.

Multidisciplinary Care

Statement 5: All Therapies

Pregnant patients may see a number of health care providers, both allied health care (such as chiropractors, midwives, and physiotherapists) and mainstream medical (such as family physicians and obstetricians), for health-related problems before pregnancy [33] and continue to do so after pregnancy. Consequently, a complete health history should include a list of these therapies. In addition, should patient information need to be communicated among health care providers with permission obtained from the patient, contact information of these providers should be sought from the patient.

Statement 6: Complementary, Integrative, and Alternative Medicine

There is limited evidence regarding many of the complementary, integrative, and alternative medicine therapies that pregnant and postpartum patients may access or use as self-care. [75-77] Chiropractors should attempt to provide care that is supportive of pregnant and postpartum patients and based on the best currently available evidence, as well as clinical experience and patient preference to ensure the application of evidence-based care. As health care providers, chiropractors should understand the current evidence on the effectiveness and safety of the therapies that their pregnant and postpartum patients may be using.

Statement 7: Interprofessional Collaboration

When pregnant and postpartum patients seek care from multiple providers, it is a valuable opportunity for interprofessional collaboration. After patient consent is obtained, and jurisdictional privacy requirements are met, a phone call, confidential health records, or reports may be shared among all providers78 so that all care provided is transparent and cohesive.

Pregnancy, LBP

Statement 8: Presentation

LBP often presents in pregnant patients as pain limited to the lumbar region (bottom of the 12th rib to the top of the iliac crests). [23, 79, 80] This pain is often described as dull and may be exacerbated by forward flexion. Spinal movement may also be restricted in the lumbar region. While palpation of the lumbar erector spinae muscles may intensify symptoms, provocation tests for pelvic pain, such as posterior pelvic pain provocation test (PPPP) and flexion, abduction, external rotation, extension (FABERE) test, [81, 82] will typically be negative. [83] Clinicians can confirm this pain by asking pregnant patients to point or indicate their pain area on a pain diagram, or use a combination of these 2 techniques. [28]

Statement 9: Key Questions

Figure 2 Although a complete history will be taken, including asking questions about previous health history, red flags, and lifestyle factors, key examination questions for pregnant patients experiencing LBP may include but are not limited to those questions found in Figure 2.

Statement 10: Risk Factors for Low Back Pain

The risk factors for LBP in pregnancy could be incorporated into questions to ask during the history part of the exam. [5, 18, 22, 24, 79, 80, 84]

Risk for LBP may include:

Prepregnancy LBP

Previous pregnancy or postpartum-related LBP

Higher anxiety scores, as measured by the state-trait anxiety inventory

Work dissatisfaction

Statement 11: Pain Pattern

There are characteristic pain patterns in pregnancy-related LBP, which may include the following: [23, 79, 80, 84–86]

Pain can start at almost any time during pregnancy but is often reported to starts around 18th week of gestation (peaking between the 24th and 36th weeks).

BP occurs in the lumbar region, between the lower rib and the iliac crests.

LBP is not as common as PGP during pregnancy; however, it is more prevalent in the postpartum period.

Pregnancy, PGP

Statement 12: Presentation

Pregnant women who present with PGP will experience pain between the tops of the iliac crest to the gluteal folds, predominantly near the sacroiliac joints and symphysis pubis, which may radiate into the posterior thigh.

There are 5 classifications of PGP [26, 28, 79, 87]:

Anterior pain at the symphysis

Unilateral sacroiliac joint pain

ilateral sacroiliac joint pain

Pain in all 3 areas (worst prognosis)

Miscellaneous pain (daily pain from one or more pelvic joints, but inconsistent objective findings from the pelvic joints)

Clinicians can confirm this pain by asking pregnant patients to point or indicate their pain area on a pain diagram, or use a combination of these 2 techniques. [28]

Statement 13: Diagnosis

Diagnosis of PGP can be reached after exclusion of a lumbar diagnosis.28 Symptoms of peripheralized pain (into the posterior pelvis or posterior thigh) do not centralize with lumbar spine testing. The pain or functional disturbances in relation to PGP must be reproducible by specific clinical tests, such as PPPP, active straight leg raise or FABERE test, or modified Trendelenburg, to name a few. [28, 81, 82, 88, 89]

Statement 14: Key Questions

Although a complete history will be taken, including asking questions about previous health history, red flags, and lifestyle factors, key examination questions for pregnant patients experiencing PGP may include but are not limited to those found in Figure 2.

Statement 15: Risk Factors for Pelvic Girdle Pain (PGP)

The risk factors for PGP listed below could be incorporated into questions to ask during the history part of the exam during pregnancy. [18, 22, 28, 90–92]

History of LBP (before and during a previous pregnancy)

Previous trauma to the pelvis

High number of pain provocation tests

Multiples pregnancy (twins, etc.)

Polyhydramnios or large for gestational age fetus

Pelvic floor muscle weakness

Work dissatisfaction

Statement 16: Pain Pattern

There are characteristic pain patterns in pregnancy-related PGP, which include: [28, 79, 86]

Onset during pregnancy

Pain between the top of the iliac crests and the bottom of the gluteal fold

Anterior, posterior, or both aspects of the pelvis

Can occur in conjunction with or separately from pain in the symphysis pubis

The pain can radiate into the posterior thigh.

PGP is more common during pregnancy than postpartum.

Pregnancy, Combined Pain

Statement 17: Presentation

Pain can occur in both the lumbar and pelvic regions simultaneously. [22–24] Clinicians can confirm this pain by asking pregnant patients to point or indicate their pain area on a pain diagram, or use a combination of these 2 techniques. [28]

Statement 18: Key Questions

Although a complete history will be taken, including asking questions about previous health history, red flags, and lifestyle factors, key examination questions for pregnant patients experiencing combined pain may include, but are not limited to those questions found in Figure 2.

Statement 19: Risk Factors for Combined Pain

The risk factors for combined pain during pregnancy, listed below, could be incorporated into questions to ask during the history part of the exam [22, 24]:

Combined pain (both in the lumbar and pelvic regions) before pregnancy

Statement 20: Pain Pattern

There are characteristic pain patterns in pregnancy-related combined pain that include the following [14, 22–24, 79]:

Pain occurring simultaneously in the lumbar region (LBP) and pain in the pelvic girdle region (PGP)

Pregnant patients who experience combined pain often experience more disability than those just experiencing LBP or PGP alone.

Postpartum, LBP

Statement 21: Presentation

Postpartum patients who present with LBP may experience pain in the lumbar region, bottom of the 12th rib to the top of the iliac crests; range of motion may be restricted and/or painful; and there maybe pain with palpation of the lumbar musculature (such as erectors, quadratus lumborum). [16, 28] Clinicians can confirm this pain by asking pregnant patients to point or indicate their pain area on a pain diagram, or use a combination of these 2 techniques. [28]

Statement 22: Key Questions

Figure 3 Although a complete history will be taken, including asking questions about previous health history, red flags, and lifestyle factors, key examination questions for postpartum patients experiencing LBP may include but are not limited to those questions found in Figure 3.

Statement 23: Risk Factors

The risk factors for LBP during the postpartum period, listed below, could be incorporated into questions to ask during the history part of the exam. [12, 13, 86, 93, 94]

A previous history of LBP before and during pregnancy

A significant earlier onset and worse pain symptoms in the preceding pregnancy

A higher postpartum weight gain and weight retention have a higher incidence of persistent pain symptoms after delivery.

Statement 24: Pain Pattern

There are characteristic pain patterns in postpartum-related LBP that include the following [79, 86, 95]:

Pain experienced in the lumbar region

Although a patient may experience both types of pain at this time, generally LBP is more common in the postpartum period than PGP.

Postpartum, PGP

Statement 25: Presentation

Postpartum patients who present with PGP will experience pain between the tops of the iliac crests to the gluteal folds, predominantly near the sacroiliac joints. The pain may radiate into the posterior thigh and may occur in conjunction with or separately from pain the symphysis pubis. [16, 84] Clinicians can confirm this pain by asking pregnant patients to point or indicate their pain area on a pain diagram, or use a combination of these 2 techniques. [28]

Statement 26: Key Questions

Although a complete history will be taken, including asking questions about previous health history, red flags, and lifestyle factors, key examination questions for postpartum patients experiencing PGP may include but are not limited to those questions found in Figure 3.

Statement 27: Risk Factors for Pelvic Girdle Pain

The risk factors for postpartum-related PGP, listed below, could be incorporated into questions to ask during the history part of the exam. [24, 28, 84, 87, 96]

Higher pain scores during pregnancy

Combined pain in early pregnancy

Pain with active straight leg raise

Prepregnancy LBP

Age ≥29 years

Low endurance of back flexors

ower socioeconomic status

Type of delivery (ie, traumatic or forceps delivery)

Epidural/spinal injection

Work dissatisfaction

elvic floor weakness

Statement 28: Pain Pattern

There are characteristic pain patterns in postpartum-related PGP that include the following [24, 84, 87, 96, 97]:

Although a patient may experience this pain, generally PGP is less common during the postpartum period than during pregnancy.

There is often a decline in prevalence of postpartum PGP within 3 months of delivery. However, those whose pain does not resolve within that time frame may be at greater risk for prolonged severe or persistent pain.

Patients presenting with PGP and combined pain during pregnancy tend to recover more slowly in the postpartum period

Postpartum, Combined Pain

Statement 29: Presentation

Postpartum patients who have combined pain will present with pain in both the lumbar and pelvic regions (posterior and/or anterior). Clinicians can confirm this pain by asking pregnant patients to point or indicate their pain area on a pain diagram, or use a combination of these 2 techniques. [28] Postpartum patients with combined pain should be identified for treatment, as they have the highest risk for persistent or chronic pain, especially if the pain continues past 3 months postpartum.

Statement 30: Key Questions

Although a complete history will be taken, including asking questions about previous health history, red flags, and lifestyle factors, key examination questions for postpartum patients experiencing combined pain may include but are not limited to those found in Figure 3.

Statement 31: Risk Factors

The risk factors for postpartum-related combined pain, listed below, could be incorporated into questions to ask during the history part of the exam. [15, 22, 84, 97]

Postpartum patients experiencing combined pain at 3 months after delivery have an increased risk for persistent pain

Work dissatisfaction

Combined pain in early pregnancy

Age ≥ 29 years

Low endurance of back flexors

Type of delivery (ie, traumatic or forceps delivery)

Epidural/spinal injection

Statement 32: Pain Pattern

There are characteristic pain patterns in postpartum-related PGP that include the following [24, 84, 87, 96]: a. Pregnant patients presenting with PGP and combined pain tend to recover more slowly and their pain has a greater impact on daily activities than lumbar pain alone in the postpartum period. If left untreated, 30% of these patients are at risk of developing persistent or chronic pain in the postpartum period.

Examination

Statement 33: Examination, General

Depending on the patient's presentation and history, clinicians should consider the following for a physical exam: range of motion of affected joints, neurological testing: deep and pathological reflexes, and palpation. Pain provocation tests for the sacroiliac joint and for the symphysis pubis should be included as well as tests of load transfer, such as active straight leg raise and standing on 1 leg. [27, 37, 38] (For more details, see statements 40-41 for LBP exam and 43-44 for PGP exam)

Statement 34: Vital Signs

Vital signs should be taken and recorded at the initial visit; these may include heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, weight, and height. [78] Although many of these vital signs are monitored by the patient's obstetric provider, some vital signs, such as blood pressure, may need to be monitored more regularly. An increase in blood pressure is a serious complication of pregnancy and may occur quickly. If there is a concerning change in vital signs or symptomology, patients should be immediately referred to their obstetric provider.

Statement 35: Blood Pressure and Hypertension, Pregnancy

As pregnant patients will potentially see a chiropractor more frequently than their primary health care provider and as pregnancy-related symptoms may change quickly, it is recommended that blood pressure be taken at the initial visit and then once every 4 weeks until 28 weeks [98] and then weekly until delivery. [99] It is also recommended that blood pressure be taken at each visit if they have any risk factors for preeclampsia. [100] Blood pressure should also be taken if there is a concerning change in vital signs or symptomology, such as persistent headache, visual disturbances (blurring, flashing, dark spots in the field of vision), epigastric pain/right upper quadrant pain, nausea and/or vomiting, chest pain, or shortness of breath [101]; patients should then be immediately referred to their obstetric provider.

Hypertension is an important and frequent complication of pregnancy and may also occur in the postpartum period. [98] Pregnancy-induced hypertension, which can lead to seizures/toxemia and possible stroke, is a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. [39, 40, 98] Hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg; based on the average of at least 2 measurements, taken at least 15 minutes apart, using the same arm. [102, 103] When taking blood pressure, the patient should be seated comfortably with their back supported. Their arm should be relaxed and supported on the armrest at heart level. If there is a concerning change in symptomology (ie, blood pressure >140/90 mmHg, new onset of headache, calf swelling, and/or edema) since the previous visit, patients should be immediately referred to their obstetric provider.

Statement 36: Blood Pressure, Postpartum

For patients seen within 3 to 6 days after delivery (the time in which blood pressure peaks postpartum), [102] blood pressure should be measured. Those with high blood pressure should immediately be referred back to their family physician, obstetrician, or midwife for evaluation of preeclampsia as it can develop postpartum. [102, 103]

Statement 37: Hypertension, Postpartum

For patients seen within the first 6 weeks after delivery, whether or not they have had a follow-up with their obstetric provider, blood pressure should be taken at the patient's first postpartum visit. Patients who present with hypertension or persistent postpartum hypertension should be immediately referred to their family physician, obstetrician, or midwife providers for further investigation. [39, 40]

Statement 38: Diastasis Recti, General

As most patients experience an increase in the inter-recti abdominal muscle distance as a result of stretching and thinning of the linea alba during pregnancy, patients should be checked for diastasis recti of the abdominal muscles (DRAM) [99, 104–108] both in the pregnant (at least once each trimester) and postpartum state (upon their first visit and periodically over the course of care, until the issue is resolved). Palpation of the linea alba to determine diastasis recti has shown good intra-rater reliability and moderate inter-rater reliability. [99] Although there is no strict recommendation as to the place of measurement or method, it is suggested that the patients start in a crooked leg position,109 lying on their back with hips and knees bent and feet flat on the floor. Hands can be by their side or across their chest. A pillow can be placed under their head for comfort. Ask the patient to perform an abdominal crunch, so that they lift their head and shoulder blades off the surface they are lying on. [107, 109] Although other tools can be used to assess DRAM, diagnosis of DRAM is rendered if horizontal palpation of the linea alba is greater than 2 fingerbreadths (or >2.5 cm). [99]

Statement 39: Diastasis Recti, Postpartum

Although for most patients DRAM resolves spontaneously in the postpartum period, [104, 109] it can still persist in some women. [109] An increase in the inter-recti abdominal muscle has been suggested to influence the strength of the abdominal wall musculature [109] possibly interfering with the ability of the abdominal muscles to stabilize the trunk; this may lead to poor posture, umbilical hernia, or pain in the low back or hip. [110, 111] Although some studies have demonstrated positive effects of exercise on DRAM, [104, 106, 112] no generally acceptable therapeutic exercise protocol has been recommended. [109] As such, an individualized assessment, manual therapy (if indicated), and individualized exercise-based rehabilitation prescription has been suggested. [107, 108]

Statement 40: Low Back Pain, General

Low back pain is diagnosed based on reproducible pain and/or change in range of motion from repeated movements or different positions of the lumbar spine [113] or experience of centralization and peripheralization phenomena during examination and negative pain provocation tests [81, 84, 114] (see Pregnancy, PGP Exam, Statements 43 and 44).

Statement 41: Low Back Pain, Specific Tests

To determine LBP in the pregnant population, an exam should include, at a minimum, range of motion of the lumbar spine, palpation of the muscles of the low back (such as the erectors), and provocation test (such as PPPP) test to rule out PGP. [79, 114]

Statement 42: Neurological Testing

Simple mechanical LBP must be differentiated from radicular and other neurological symptoms. To rule out red flags as causes of LBP, clinicians should perform a neurological exam including deep and pathological reflexes, motor and sensation, as well as nerve root tension tests. [113]

Statement 43: Pelvic Girdle Pain, General

Criteria for diagnosis of PGP are 3 or more positive pain provocation tests for the sacroiliac joints, [82, 115, 116] testing for symphysis pubis irritation, the absence of centralization or peripheralization phenomena during repeated movement assessment, and no lumbar pain or change in range of motion from repeated movements.

Statement 44: Pelvic Girdle Pain, Specific Tests

Tests to determine PGP should include pain provocation tests such as the PPPP test and FABERE test, as they have the best sensitivity and specificity for determining pain at the sacroiliac joint. [28, 79] Other tests to consider include Gaenslen's test, compression test, sacral thrust or distraction test, and palpation of the long dorsal sacroiliac joint ligament. [28, 79] There is high specificity for the active straight leg test in this population, and when combined with PPPP the sensitivity is higher than alone. If there is persistent pain at the symphysis pubis, testing may include palpation of symphysis pubis, the modified Trendelenburg test, and the active straight leg test. [28, 79]

Statement 45: Red Flags

Clinicians should identify and monitor for red flags (see statement 46). If the patient presents with 1 or more red flags that would contraindicate a specific type of treatment (eg, SMT, mobilization, or other treatment modalities), that treatment should stop and the clinician should refer the patient to an appropriate provider for further evaluation and/or care. [79, 117] Chiropractic care may need to be modified or adapted as deemed appropriate if monitoring for red flags is ongoing. Co-management and/or consultation with the patient's obstetric provider is encouraged.

Statement 46: Contraindications and Red Flags

There is limited research on contraindications of spinal therapies for pregnant patients. Until more evidence is available, caution is recommended when performing high-velocity SMT to the lower thoracic, lumbar, and pelvic regions for patients with the following [72, 118, 119]:

Vaginal bleeding—without prior clearance from prenatal providers

Abdominopelvic cramping

Ruptured membranes, premature labor, imminent birth

Placenta previa (full implantation on the cervix accompanying vaginal bleeding)

Placenta abruption

Ectopic pregnancy

Sudden onset of pelvic pain (not reproducible with orthopedic testing) or other reasons to suspect ectopic pregnancy)

Bowel obstruction

Pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia, or eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia (moderate to severe)

Recent trauma (ie, fall, car accident) to the pelvis that might threaten the pregnancy

Caution is recommended for other chiropractic treatment modalities (ie, soft tissue therapy, spinal adjustments/SMT, mobilization, and therapeutic exercise) of the pregnant patient experiencing:

High-risk situations (suggest obtaining prior clearance from obstetric providers), such as:

Multiples

History of miscarriages/still births

Patients who smoke (the literature indicates they may be at increased risk for pregnancy-related complications)

Pre-eclampsia (moderate to severe)

Known bleeding disorders

If a patient presents with any of the above, it is recommended that an appropriate plan of management be communicated and discussed with the patient, and whenever possible a discussion with the patient's obstetric provider.

Statement 47: Contraindications

Very little is known regarding red flags specifically for SMT of the postpartum patient. However, in the non-pregnant adult patient, there may be contraindications to spinal manipulation within the area of pathology/abnormality/device or its immediate vicinity. [74] Some of these contraindications may be absolute (in which any use of joint manipulation or mobilization is inappropriate, as it may place the patient at undue risk) or relative in nature (the treatment may place the patient at undue risk unless the presence of the relative contraindications is understood and the proposed treatment is modified). Other chiropractic care options to high velocity should be considered and discussed with the patient if these are present. The World Health Organization and other clinical guidelines have published a list of contraindications to high-velocity SMT. [74]

Anomalies such as dens hypoplasia, unstable os odontoideum, etc.

Acute fracture

Spinal cord tumor

Acute infection such as osteomyelitis, septic discitis, and tuberculosis of the spine

Meningeal tumor

Hematomas, whether spinal cord or intracanalicular

Malignancy of the spine

Frank disc herniation with accompanying signs of progressive neurological deficit

asilar invagination of the upper cervical spine

Arnold-Chiari malformation of the upper cervical spine

Dislocation of a vertebra

Aggressive types of benign tumors, such as an aneurismal bone cyst, giant cell tumor, osteoblastoma, or osteoid osteoma

nternal fixation/stabilization devices

Neoplastic disease of muscle or other soft tissue

Positive Kernig's or Lhermitte's signs

Congenital, generalized hypermobility

Signs or patterns of instability

Syringomyelia

Hydrocephalus of unknown etiology

iastematomyelia

Cauda equina syndrome

Interventions

Statement 48: Radiographs

All female patients of childbearing age should be asked if it is possible that they are pregnant before radiographs being conducted. [120]

Statement 49: Radiographs

For pregnant patients in which radiographs are medically indicated (ie, trauma), ensure the beam is collimated properly so the fetus will not be in the field of view and the patient is positioned to avoid direct irradiation of the pelvis and gravid uterus is covered with a radiation shield. [121]

Statement 50: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

One of the concerns for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in pregnant patients is the necessity of lying supine for an extended period. [122] In the event that a pregnant patient requires an MRI, ordered by either a chiropractor or another provider, the chiropractor can educate the patient regarding alternative positions. If the patient cannot tolerate lying on her back as a result of lightheadedness, nausea, and dizziness, the chiropractor can suggest alternative positions, such as using a pillow or wedge to help the patient into the lateral decubitus position. [122] In addition, the chiropractor can also encourage the patient to discuss and/or advocate for any of these options with the personnel taking the imaging.

Statement 51: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Although the use of obstetrical MRI varies from region to region, MRI during pregnancy, in particular trimester 1, should be used with caution (as there are hypothetical concerns for the fetus including heating of sensitive tissues by radiofrequency fields and exposure to the loud acoustic environment). [122] The decision to use MRI is based on maternal indications for which the information is considered clinically imperative and the benefits outweigh the risks [122] For those chiropractors who have the ability to order advanced imaging, coordination with the obstetrical provider and radiologist is advised to ensure best practices for the pregnant patient.

Statement 52: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI plus contrast (ie, gadolinium) should be avoided in pregnant women, unless the risks outweigh the benefits [122, 123] MRI plus contrast can be administered to postpartum women; those who are breastfeeding can do so without interruption to their breastfeeding schedule. [103, 104] For those chiropractors who have the abillity to order advanced imaging, coordination with the obstetrical provider and radiologist is advised to ensure best practices for the pregnant or postpartum pateint.

Interventions

Statement 53: Introductory Statement

Pregnancy- [5, 22, 24, 84] and postpartum-related [93, 96, 97, 124] back pain (LBP, PGP, or combined pain) are very common. In addition to in-office chiropractic treatments such as SMT, mobilization, soft tissue therapy, and therapeutic exercise, supportive therapies, and other modalities, chiropractors can direct patients to use safe self-care interventions (such as home exercise, use of pelvic belts or pillows) that may help patients manage their pregnancy- or postpartum related back pain.

Statement 54: Self-Care

Clinicians should encourage pregnant women with LBP to stay active and continue normal activities if possible, [125, 126] and to follow an individual exercise program. [127–130]

Statement 55: Manual Therapy, General

The clinician should adapt SMT and soft tissue techniques and procedures to support the needs and comfort of the patient. [72, 118, 119] Pregnant and postpartum patients may require modifications to therapies depending on the time of parturition and overall comfort level of the patient. [72, 119]

Statement 56: Spinal Manipulative Therapy

High-velocity SMT may be an appropriate treatment for some pregnant and postpartum women with LBP, PGP, or combined pain [28, 55] (See statement 46 and 47 for contraindications to SMT.)

Statement 57: Spinal Manipulative Therapy & Adverse Events

High-velocity SMT for the pregnant and postpartum patients can be considered safe and may have only minor side effects occurring with lumbar SMT. [70] Regarding cervical SMT, adverse events are extremely rare in the pregnant and postpartum populations with only a few case reports. [70]

Statement 58: Spinal Manipulative Therapy & Pelvic Girdle Pain

There are no studies examining PGP and SMT alone, so a trial course of care may be warranted to see if symptomatic relief is achieved. [28] If after a trial of care there is no pain relief or improved quality of life, the patient should be reevaluated, and the management plan of may need to be modified or discontinued or the patient may need to be referred to another health care provider for further evaluation and/or co-management. [28]

Statement 59: Soft Tissue Therapy

There is no evidence specific for pregnant or postpartum population who experience LBP, PGP, or combined pain regarding the effectiveness or safety of soft tissue therapy (STT) such as Active Release and Graston instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization. There is limited evidence for massage therapy for these populations. [77, 131] A trial of care for STT may be reasonable to consider for the pregnant and postpartum population.

Statement 60: Taping

There is limited evidence for using taping for pregnant and postpartum patients with LBP, PGP, or combined pain. [132] A trial of care maybe considered. [133–135] Clinicians should be aware that some patients may have an allergy to the tape's adhesive material and should ask the patient about skin sensitivity before applying tape. In addition, should the patient have a reaction to the tape, it should be removed immediately and not reapplied. [136]

Statement 61: Pelvic or Abdominal Belts

There is limited evidence for the use of pelvic or abdominal belts in pregnant and postpartum patients who are experiencing LBP, PGP, or combined pain. [137–139] One study suggests that wearing a support belt compared to no specific treatment may be beneficial.139 A pelvic belt may be tried to provide symptomatic relief and applied for only short periods. Belts for PGP should be worn just below the anterior superior iliac spine rather than at the level of the symphysis pubis. [79]

Statement 62: Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

There is a paucity of evidence for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS); however, has been used by pregnant women. [140] There are no known adverse events to the mother or fetus associated with electrostimulation when being used as an adjunct modality to relieve pregnancy-related back pain. [140] If treatment options including advice for activities of daily living, exercises, and/or manual therapies do not provide pain relief for the pregnant or postpartum patient, and the alternative may be medication that would cross the placental barrier, a trial of TENS care could be considered. [140] This trial of care should be coupled with other recommended treatment options such as advice, exercise, and manual therapy (SMT). [141 ]

Cautions and precautions to consider with TENS include the following140:

The usual contraindications and precautions should be observed.

Extra caution should be taken if the patient has epilepsy or a very irritable uterus or if she has a history of early miscarriage or abortion. Informed consent should be obtained, and clinical judgement should be made in conjunction with her obstetrical provider.

Current density should be kept low.

Placement of pads should be considered. Caution should be taken when placing TENS electrodes on or over acupuncture points that are considered to most likely induce labor.

If the patient has a pacemaker or defibrillator, TENS should be avoided unless approval and specific parameters are provided by their cardiologist.

Statement 63: Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation and Acupuncture

Although the evidence for TENS during pregnancy is scarce, it may reduce pain and disability and appears to be a safe treatment choice during pregnancy. [142] The usual precautions and contraindications should be observed, and the placement of electrodes for LBP and PGP is likely most effective when applied posteriorly over the lumbosacral nerve roots (ie, avoid electrode placement suprapubically). [143] In addition, the current density should be kept low and the areas such as locations for acupuncture points used to induce labor should be avoided.79 Although the safety of acupuncture in pregnancy is considered reasonably safe, there is still some debate regarding needling points that could induce labor. [144] The sites most frequently cited as contraindicated before 37 weeks include Spleen 6 (SP6), Liver 4 (LI4), Bladder 60 (BL60), Gallbladder 21 (GB21), Lung 7 (LU7), and points in the lower abdomen and sacral region. [144–146]

Statement 64: Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Although the evidence for TENS during labor is not strong, patients who have used it during labor would use it again. [147] Therefore, it may be offered as pain relief with or without other pharmacological or nonpharmacological agents. [147]

Statement 65: Manual Therapy, Instrument-Assisted Therapy

There is limited evidence for instrument-assisted manual therapies, such as the Activator, chiropractic table drop-pieces, or instrument-assisted STT (ie, Graston) in the pregnant or postpartum populations. Thus, a trial of care may be warranted taking into consideration that evidence-based care includes consideration of each of the best available evidence, doctor experience, and expertise, as well as patient preference and values. [79, 85, 148, 149]

Lifestyle Factors

Statement 66: Rehabilitation Advice

Patients experiencing LBP and/or PGP should be encouraged to take an active part in their treatment or rehabilitation regardless of which state of parturition they are in. Clinicians should present patients with general information on anatomy, biomechanics, and controlled movement patterns. In a patient experiencing a healthy pregnancy, the patient should be reassured that mild back or pelvic symptoms due to mechanical musculoskeletal issues are common, not dangerous (or their child if pregnant) and that they should improve and/or recover. [150]

Statement 67: Activities of Daily Living, General

While experiencing pregnancy or postpartum-related back pain, patients should be informed to do their best to continue with their activities of daily living (such as dressing, caregiving, and physical activities). [118] In addition, patients should be taught how to avoid maladaptive movement patterns while staying active. [25] Patients should be educated to incorporate physical activity into their daily life and integrate it with periods of rest to recuperate. [28]

Statement 68: Exercise

Land-based exercises:

Pregnant and postpartum patients with LBP and/or PGP may benefit group exercise programs (eg, a 12-week program). [129]

A program of exercise plus patient education has a positive effect on pain. [148, 151–154]

For pregnant and postpartum patients, a supervised treatment program with exercises that include local and global muscle systems, individually adapted to fitness and pain levels of the patient, [128, 155] shows the best effects.

Exercises should be individualized, focusing on stability exercises as part of a multifactorial treatment for PGP postpartum. [58]

Statement 69: Exercise

Water-based exercises:

Pregnant and postpartum patients with LBP and/or PGP should be encouraged to try water-based exercises. [151, 156] They are considered safe and effective for the management of pregnancy-related LBP and may help to reduce pain intensity and sick leave. [157]

Statement 70: Information and Ergonomic Advice

An individually tailored training program may be considered in a trial of care that includes information and ergonomic advice for pregnant patients with LBP. [13, 58, 150, 158, 159]

Statement 71: Pillows

Pregnant patients may consider pillow support under the abdomen, legs, or knees to help alleviate pregnancy-related back pain and possibly improve sleep habits. [79, 160]

Discussion

This consensus process by a multidisciplinary group experts developed the first comprehensive best practice recommendations for chiropractic care of pregnant and postpartum patients with LBP, PGP, or combined pain. The article was designed so that the practitioner could identify the specific patient presentation and determine the appropriate management of these 2 populations, which will contribute to set proper expectations of all stakeholders when pregnant and postpartum women are seen by a chiropractor for their back pain. This may also provide additional options for pre- and postnatal back pain management that health care providers can offer their patients. The consensus statements provide safe, reasonable, and rational parameters for clinical management.

Similar to other best-practice recommendations, [36, 52, 61] this article may inform stakeholders to take a reasonable approach to chiropractic care for the pregnant and postpartum population. In addition to chiropractors, other health care providers can use this article(1) to understand the type of care chiropractors can provide for these populations, and

2) to inform their pregnant and postpartum patients about treatment options.Payers (such as insurance companies) and regulatory agencies may use this information to inform decisions regarding chiropractic care for the pregnant and postpartum populations.

Limitations

While this study did not intend to assess outcome measures, this is another area for further exploration. Although there are several validated instruments to assess back pain in the nonpregnant populations, they were not designed with pregnant and postpartum patients in mind and may not be valid for these specific populations. Pregnant women with back pain may be less mobile and experience a lower quality of life, as they have more difficulty with ADLs than the nonpregnant population. [161]

There are few outcome measures available for this population, such as the Pregnancy Mobility Index [161] and Pelvic Girdle Pain Questionnaire [162]; however, they have not been validated. Based on our review of the literature, these are rarely used as outcome measures for these 2 populations.

Our original aim for this study was to recruit an international panel to obtain consensus. We thought this would have been achieved by recruiting the attendees of an international chiropractic conference; however, most attendees were from Canada or the United States. Although these recommendations are general in nature and we have stated clearly that the reader should stay within the guidelines of their regional regulators, these recommendations will be most applicable to practitioners in Canada and the United States.

We tried to delineate and present the information regarding 3 types of musculoskeletal pain (LBP, PGP, and combined pain) within this best-practice study; the research delineating these pains is lacking. As such, expert opinion was used more on these topics. Additionally, to fully make this a resource for chiropractic education, an audit of pregnancy and postpartum chiropractic care in the curricula at chiropractic colleges should be conducted to determine exactly what is being taught. This audit would be even more prudent if it included postgraduate educational programs for pre- and postpartum patients. This information would help determine if a standardized curriculum exists, and if not, one could be developed so that educational institutions could update their curriculum and all stakeholders would know what to expect from chiropractic care for pregnant and postpartum women.

Although this best-practice article focused on the common treatment options for these 2 populations, we were limited to that reported in the literature. While limited, the modality of SMT has a start to an evidence base; however, this literature doesn't accurately reflect how SMT and its many variations (eg, provider used instrument or table assisted) is offered to most patients.

Additionally, chiropractic techniques not necessarily taught in chiropractic colleges (ie, Webster technique and STT), nutritional supplements, dietary interventions, and other complementary and alternative medicine (ie, osteopathy, hypnobirthing, acupuncture) could be further explored and part of a future consensus process, as chiropractors may be trained in these modalities.

Another limitation to using the current literature is that adverse events from modalities aside from SMT may not be reported (eg, hot pack or electrical stim burns, dermatitis from taping, soreness from therapeutic exercises, resistance bands injuries).

Conclusion

This best-practice recommendations article is a synthesis of the current evidence and collective expert opinion about a reasonable clinical approach for chiropractic care and management of pregnant and postpartum populations. This article provides an initial framework for chiropractors who wish to manage these populations and to help chiropractic researchers determine and examine the gaps in the literature to implement a robust research program that informs future clinical guidelines. As the first best-practices recommendations document for pregnant and postpartum patients, it is expected to evolve as new evidence emerges.

Practical Applications

The consensus process, using both a multidisciplinary steering committee and panel, was successful in developing a set of seed statements regarding the key issues related to chiropractic care for pre- and postpartum patients.

These recommendations provide an evidenced-based framework for the chiropractic management of pregnant and postpartum patients.

This is an iterative document that should be periodically updated as new evidence emerges.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following panel members for their contributions and who consented to be acknowledged for this work: Sean Armstrong, Daniela Arciero, Holly Beckley, Cecilia Bergstrom, Alison Brown, Wayne Carr, Philippa Carrie, Samantha R. Colautti, Matthew Coté, Elisabeth Davidson, Melissa Diaz, Lisa Dickson, Chantale Doucet, Drew Fogg, David Folweiler, Ryan French, Jennifer Forbes, Jason Guben, Melissa Ferranti, Judy Forrester, Kait Graham, Stacy Hallgren, Kaitlin Hanmer, Vicki Hemmett, Emily Howell, Michelle Minjung Kang, Susan Kees, Jolene Kuty, William Lawson, Paul Lee, Lynda McClatchie, Aaron McMichael, Sarah Mickler, Erica Michitsch, Vanessa Morales, Kara Mortifoglio, Natalie N. Muth, Frank Nhan, Cora-Lee Peddle, Tara Price, Sarah Radabaugh, Corinne Roughsedge, Vern Saboe, Kristine Salmon, Scott Siegel, Amanda Stevens, Tonya Tyre, Sarah Vallone, Brenda van der Vossen, Susan Wenberg, Debbie Wright, Francesca Wuytack.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

This study was partially funded by the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College (internal grant) and the Ontario Chiropractic Association . Drs Weis, Pohlman, Stuber, Draper report grants from CMCC/OCA for travel bursaries.

Dr. Hawk reports personal fees, and Drs. Barrett, Kumar and Clinton report receiving honoraria. No other conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): C.A.W., C.H., K.P., K.S., C.D.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): C.A.W., C.H., K.P., K.S., C.D.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): C.A.W., C.H., K.P., K.S.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): C.A.W., J.L. C.A.W., C.H., K.P., K.S., C.D., S.D.O., R.K., S.C., J.B., M.O.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): C.A.W., J.L., C.A.W., C.H., K.P., K.S., C.D., S.D.O., R.K., S.C., J.B., M.O.

Literature search (performed the literature search): C.A.W., C.H., K.P., K.S., C.D., S.D.O.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): C.A.W., J.L., C.A.W., C.H., K.P., K.S., C.D., S.D.O., R.K., S.C., J.B., M.O.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): C.A.W., J.L., C.A.W., C.H., K.P., K.S., C.D., S.D.O., R.K.,. S.C., J.B., M.O.

References:

Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al.

A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain

Arthritis Rheumatol. 2012; 64: 2028-2037Hoy, D, March, L, Brooks, P et al.

The Global Burden of Low Back Pain:

Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study

Annals of Rheumatic Diseases 2014 (Jun); 73 (6): 968–974Browning M

Low Back and Pelvic Girdle Pain of Pregnancy:

Recommendations for Diagnosis and Clinical Management

J Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 2010 (Dec); 11 (2): 775—779Ansari N Hasson S Naghdi S Keyhani S Jalaie S

Low back pain duirng pregnancy in Iranian women.

Physiother Theory Pract. 2010; 26: 40-48Malmqvist S Kjaermann I Andersen K Økland I Brønnick K Larsen J

Prevalence of low back and pelvic pain during pregnancy in a Norwegian population.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012; 35: 272-278Ramachandra P Maiya A Kumar P Kamath A

Prevalence of musculoskeletal dysfunctions among Indian pregnant women.

J Pregnancy. 2015; 15437105Stapleton DB MacLennan AH Kristiansson P

The prevalence of recalled low back pain during and after pregnancy:

a South Australian population survey.

Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002; 42: 482-485Kristiansson P Savardsudd K von Schoultz B

Back pain during pregnancy. A prospective study.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996; 21: 702-709Sabino J Grauer JN

Pregnancy and low back pain.

Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008; 1: 137-141Perkins J Hammer R Loubert P

Identificiation and management of pregnancy-related low back pain.

J Nurse Midwifery. 1998; 43: 331-340Ostgaard H Andersson G Karlsson K

Prevalence of back pain in pregnancy.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991; 16: 549-552Ostgaard H Andersson G

Postpartum low-back pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992; 17: 53-55Ostgaard H Zetherström G Roos-Hansson E

Back pain in relation to pregnancy: a 6-year follow-up.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997; 22: 2945-2950Norén L Ostgaard S Johansson G Ostgaard HC

Lumbar back and posterior pelvic pain during pregnancy: a 3-year follow-up.

Eur Spine J. 2002; 11: 267-271Gutke A Lundberg M Ostgaard H Oberg B

Impact of postpartum lumbopelvic pain on disability, pain intensity,

health-related quality of life, activity level, kinesiophobia, and depressive symptoms.

Eur Spine J. 2011; 20: 440-448Tavares P Barrett J Hogg-Johnson S et al.

Prevalence of low back pain, pelvic girdle pain, and

combination pain in a postpartum Ontario population.

J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020; 42: 473-480Endresen E

Pelvic pain and low back pain in pregnant women - an epidemiological study.

Scand J Rheumatol. 1995; 2: 135-141Kovacs FM Garcia E Royuela A González L Abraira V

Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain and pelvic girdle pain

during pregnancy: a multicenter study conducted in the Spanish National Health Service.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012; 37: 1516-1533Turgut F Turgut M Cetinsahin M

A prospective study of persistent back pain after pregnancy.

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998; 80: 45-48Schytt E Lindmark G Waldenström U

Physical symptoms after childbirth: prevalence and associations with self-rated health.

Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005; 112: 210-Lindal E Hauksson A Arnardottir S Hallgrimsson J

Low back pain, smoking and employment during pregnancy and after delivery -

a 3-month follow-up study.

J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000; 20: 263-266Weis C Barrett J Tavares P et al.

Prevalence of low back pain, pelvic girdle pain, and combination pain

in a pregnant Ontario population.

J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018; 40: 1038-1043Gutke A Ostgaard H Oberg B

Pelvic girdle pain and lumbar pain in pregnancy: a cohort study

of the consequences in terms of health and functioning.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006; 31: 149-155Wu W Meijer O Uegaki K et al.

Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I:

terminology, clinical presenation and prevalence.

Eur Spine J. 2004; 13: 575-589De Alencar Gomes M de Araujo R Lima A Rodarti Pitangui A.

A gestational low back pain:

prevalence and clinical presenations in a group of pregnant women.

Revista Dor. 2013; 14Albert H Godskesen M Westergaard J

Incidence of four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002; 27: 2831-2834Mohseni-Banpei M Fakhri M Ahmad-Shirvani M et al.

Iranian pregnant women: prevalence and risk factors.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009; 9: 795-801Vleeming A Albert H Ostgaard H Sturesson B Stuge B

European Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pelvic Girdle Pain

European Spine Journal 2008; 17 (6): 794–819Pierce H Homer CSE Dahlen HG King J

Pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: listening to Australian women.

Nurs Res Pract. 2012; 2012387428Bergström C Persson M Mogren I

Sick leave and healthcare utilisation in women reporting pregnancy related

low back pain and/or pelvic girdle pain at 14 months postpartum.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2016; 24: 7Wuytack F Curtis E Begley C

Experiences of first-time mothers with persistent pelvic girdle pain

after childbirth: descriptive qualitative study.

Phys Ther. 2015; 95: 1354-1364Wuytack F Curtis E Begley C

The health seeking behaviours of first-time mothers with persistent

pelvic girdle pain in Ireland: A descriptive qualitative study.

Midwifery. 2015; 31: 1104-1109Wang S-M DeZinno P Fermo L et al.

Complementary and alternative medicine for low-back pain in pregnancy:

a cross-sectional survey.

J Altern Complement Med. 2005; 11: 459-464Sadr S, Pourkiani-Allah-Abad P, Stuber KJ:

The Treatment Experience of Patients with Low Back Pain

During Pregnancy and Their Chiropractors: A Qualitative Study

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2012 (Oct 9); 20 (1): 32Allaire AD Moos MK Wells SR

Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Low-back Pain in Pregnancy:

A Cross-sectional Survey

J Altern Complement Med. 2005 (Jun); 11 (3): 459-64Hawk, C, Schneider, M, Ferrance, RJ, Hewitt, E, Van Loon, M, and Tanis, L.

Best Practices Recommendations for Chiropractic Care for Infants,

Children, and Adolescents: Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Oct); 32 (8): 639–647Beliveau PJH, Wong JJ, Sutton DA, Simon NB, Bussieres AE, Mior SA, et al.

The Chiropractic Profession: A Scoping Review of Utilization Rates,

Reasons for Seeking Care, Patient Profiles, and Care Provided

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Nov 22); 25: 35Herman PM, Coulter ID:

Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Professions or Modalities?

Policy Implications for Coverage, Licensure, Scope of Practice,

Institutional Privileges, and Research.

RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California: (2015. pp. 1–76)Wong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, et al.

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Noninvasive Management of

Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review by the Ontario Protocol for

Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

European J Pain 2017 (Feb); 21 (2): 201–216Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr., Shekelle P, Owens DK:

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline

from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 478–491Bussieres AE Stewart G Al Zoubi F Decina P Descarreaux M Hayden J

The treatment of whiplash and neck pain associated disorders:

Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative clinical practice guideline.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016; 39: 523-604Cote, P., Wong, J.J., Sutton, D. et al.

Management of Neck Pain and Associated Disorders: A Clinical Practice Guideline

from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

European Spine Journal 2016 (Jul); 25 (7): 2000-2022Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, Decina P, Descarreaux M, Haskett D, Hincapie C, et al.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Other Conservative Treatments for Low Back Pain:

A Guideline From the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (May); 41 (4): 265–293Bishop PB, Quon JA, Fisher CG, Dvorak MF.

The Chiropractic Hospital-based Interventions Research Outcomes (CHIRO) Study:

A Randomized Controlled Trial on the Effectiveness of Clinical Practice Guidelines

in the Medical and Chiropractic Management of Patients with Acute Mechanical Low Back Pain

Spine J. 2010 (Dec); 10 (12): 1055-1064McMorland G Suter E

Chiropractic managment of mechanical neck and low back pain:

a retrospective, outcome-based analysis.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000; 23: 307-311Nelson C

Principles of effective headache management.

Top Clin Chiropr. 1998; 5: 55-61Bryans R Dacina P Descarreaux M et al.

Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Chiropractic Treatment of Adults With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Jan); 37 (1): 42–63Cassidy JD, Boyle E, Cote P, et al.

Risk of Vertebrobasilar Stroke and Chiropractic Care: Results of a Population-based

Case-control and Case-crossover Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S176–183Heiner JD

Cervical epidural hematoma after chiropractic spinal manipulation.

Am J Emerg Med. 2009; 27 (1023.e1-2)Schmitz A Lutterbey G von Engelhardt L von Falkenhausen M Stoffel M

Pathological cervical fracture after spinal manipulation in a pregnant patient.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005; 28: 633-636Oliphant D.

Safety of Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Lumbar Disk Herniations:

A Systematic Review and Risk Assessment

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (Mar); 27 (3): 197–210Hawk C Schneider M Dougherty P Gleberzon B Killinger L

Best Practices Recommendations for Chiropractic Care for Older Adults:

Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Jul); 33 (6): 464–473Hurwitz E Morgenstern H Vassilaki M Chiang L

Frequency and clinical predictors of adverse reactions to

chiropractic care in the UCLA neck pain study.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005; 30: 1477-1478Lisi AJ:

Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation for Low Back Pain of Pregnancy:

A Retrospective Case Series

J Midwifery Womens Health 2006 (Jan); 51 (1): e7-10Khorsan R, Hawk C, Lisi AJ, Kizhakkeveettil A

Manipulative Therapy for Pregnancy and Related Conditions: A Systematic Review

Obstet Gynecol Surv 2009 (Jun); 64 (6): 416–427Stuber KJ, Smith DL

Chiropractic Treatment of Pregnancy-related Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review of the Evidence

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 (Jul); 31 (6): 447–454Yuen T Wells K Benoit S Yohanathan S Capelletti L Stuber K

Therapeutic interventions employed by Greater Toronto Area chiropractors

on pregnant patients: results of a cross-sectional online survey.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2013; 57: 132-142George JW, Skaggs CD, Thompson PA, et al.

A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing a Multimodal Intervention

and Standard Obstetrics Care for Low Back and Pelvic Pain in Pregnancy

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 (Apr); 208 (4): 295.e1-7Stuber KJ:

The Safety of Chiropractic During Pregnancy:

A Pilot Email Survey of Chiropractors’ Opinions

Clin Chiropr 2007 (Mar): 10 (1): 24–35Weis CA Stuber K Barrett J et al.

Attitudes toward chiropractic: a survey of Canadian obstetricians.

J Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2016; 21: 92-104Hawk C, Schneider MJ, Vallone S, Hewitt EG.

Best Practices for Chiropractic Care of Children: A Consensus Update

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Mar); 39 (3): 158–168Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, et al.

Best-Practice Recommendations for Chiropractic Management of Patients With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 635-650Globe, G, Farabaugh, RJ, Hawk, C et al.

Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 1–22Driever M

Are evidence-based practice and best practice the same?.

West J Nurs Res. 2002; 24: 591-597Weis CA Pohlman KA Draper C da Silva-Oolup S Stuber K Hawk C

Chiropactic care of adults with postpartum-related low back,