Can a Bothersome Course of Pelvic Pain From Mid-pregnancy

to Birth be Predicted? A Norwegian Prospective

Longitudinal SMS-Track StudyThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: BMJ Open. 2018 (Jul 25); 8 (7): e021378 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Stefan Malmqvist, Inger Kjaermann, Knut Andersen, Anne Marie Gausel, Inger Økland, Jan Petter Larsen, Kolbjorn S Bronnick

The Norwegian Centre for Movement Disorders,

Stavanger University Hospital,

Stavanger, Norway.

OBJECTIVE: To explore if pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain (PGP), subgrouped following the results from two clinical tests with high validity and reliability, differ in demographic characteristics and weekly amount of days with bothersome symptoms through the second half of pregnancy.

DESIGN: A prospective longitudinal cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS: Pregnant women with pelvic and lumbopelvic pain due for their second-trimester routine ultrasound examination.

SETTING: Obstetric outpatient clinic at Stavanger University Hospital, Norway.

METHODS: Women reporting pelvic and lumbopelvic pain completed a questionnaire on demographic and clinical features. They were clinically examined following a test procedure recommended in the European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PGP. Women without pain symptoms completed a questionnaire on demographic data. All women were followed weekly through an SMS-Track survey until delivery.

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY OUTCOME MEASURES: The outcome measures were the results from clinical diagnostic tests for PGP and the number of days per week with bothersome pelvic pain.

RESULTS: 503 women participated. 42% (212/503) reported pain in the lumbopelvic region and 39% (196/503) fulfilled the criteria for a probable PGP diagnosis. 27% (137/503) reported both the posterior pelvic pain provocation (P4) and the active straight leg raise (ASLR) tests positive at baseline in week 18, revealing 7.55 (95% CI 5.54 to 10.29) times higher mean number of days with bothersome pelvic pain compared with women with both tests negative. They presented the highest scores for workload, depressed mood, pain level, body mass index, Oswestry Disability Index and the number of previous pregnancies. Exercising regularly before and during pregnancy was more common in women with negative tests.CONCLUSION: If both active straight leg raise (ASLR) and posterior pelvic pain provocation (P4) tests were positive mid-pregnancy, a persistent bothersome pelvic pain of more than 5 days per week throughout the remainder of pregnancy could be predicted. Increased individual control over work situation and an active lifestyle, including regular exercise before and during pregnancy, may serve as a PGP prophylactic.

There are more articles like this @ our:

Chiropractic Pediatrics Section and the:

Clinical Prediction Rule Page and the:

Pregnancy-related Pain and Chiropractic Page

KEYWORDS: back pain; maternal medicine; musculoskeletal disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study

We used a prospective design with SMS-Track system in data collection, providing instant data on participants’ situation, with automatically recorded responses in a database, which minimises further data handling and risk of error.

We applied clinical diagnostic tests with high validity and reliability, recommended in the international guidelines for the diagnosis of pelvic musculoskeletal affliction in pregnancy.

There were frequent problems in reaching the participants through some of the phone providers, which led to SMS-Track data missing at random, but a generalised estimating equation analytic approach compensates for missing data in these instances.

The retrospectively collected information on pelvic pain in previous pregnancies and pelvic pain before pregnancy may produce bias.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) during pregnancy affects approximately half of all pregnant women, and for 25%–30% the condition becomes severe. [1, 2] The aetiology of PGP is still unknown, and the underlying mechanisms have not been fully investigated. [1, 2] Researchers have explored the physical, psychological and socioeconomic implications of PGP during pregnancy. [3] Pain-related restrictions on physical activity have been described, both during pregnancy and after childbirth, and the psychological impact on perceived health, sexual life and quality of life has been explored, as well as the prevalence of sick leave due to PGP. [3–6]

PGP is classified into specific (caused by trauma) or non-specific (multifactorial). [3] Several clinical tests are needed to diagnose the latter, including pain provocation and functional ability tests. However, there is still no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosing PGP. The European guidelines present evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of PGP, but inconsistencies on the definition as well as treatment still prevail. [3, 7]

Classification of PGP can, according to guidelines, only be reached after lumbar causes have been excluded through a clinical examination. [7] All tests recommended in the European guidelines have a very high specificity, but generally a low sensitivity. Hence, it is recommended to perform all the tests, as one negative test is not sufficient to rule out PGP. [7] The posterior pelvic pain provocation test (P4), for diagnosing sacroiliac joint dysfunction, and the active straight leg raise test (ASLR), for detecting failing force closure, have shown high validity and reliability. [8–10] In a Swedish study, substantial agreement between examiners using ASLR and P4 tests was found in discriminating non-specific lumbopelvic pain into lumbar pain and PGP in pregnant women. [11] Together with a description of pain location, these tests are considered relevant when evaluating affliction in pregnant women likely to have PGP. [12]

So far, the longitudinal course of PGP in pregnancy is incompletely examined. In prospective studies data are usually collected at baseline and at one or a few follow-ups. Measuring only at a few points in time may indicate stability in the examined condition, and a fluctuating course may be missed. A difference could reflect only a temporary fluctuation in an otherwise stable condition. Accordingly, a more frequent data collection is warranted to accurately describe the clinical course. Mobile phones and text messages have previously been found feasible when collecting frequent longitudinal data in clinical settings. [13–15] Phones are usually at hand in daily life; hence, this method yields a high response rate for weekly measures.

The objective of this study was to explore if pregnant women with probable PGP, subgrouped following the results from two valid and reliable clinical tests recommended in the European guidelines, differ in demographic and clinical characteristics at mid-pregnancy and in weekly amount of days with bothersome symptoms through the second half of pregnancy. The hypothesis was that sacroiliac dysfunction and failing force closure diagnosed at mid-pregnancy may predict a course of bothersome symptoms through the second half of pregnancy.

Methods

This is a prospective longitudinal cohort study of pregnant women who had their second-trimester routine ultrasound examination in pregnancy week 18 at an obstetric outpatient clinic at Stavanger University Hospital, Norway, from mid-March to mid-June 2010. At the hospital, all the women were asked by a midwife about their experience of pain in the lumbopelvic region. The inclusion criteria were current lumbopelvic pain or isolated pelvic pain, singleton pregnancy and good proficiency in the Norwegian language. Women who met the criteria were informed about the study, handed a letter of consent to fill in if they agreed to participate, and an envelope with questionnaires on demographic and clinical data to complete at home. An appointment with a chiropractor for a physical examination was arranged, and the women were asked to bring the completed questionnaires with them to the consultation. Women without pain symptoms were informed about the study, handed a letter of consent to fill in if they agreed to participate, and a questionnaire on demographic data to complete and leave at the reception on departure. All consenting women were followed from week 18 with weekly, automated text messages (SMS-Track).

Two chiropractors (SM and IK) performed a physical examination of the pelvic region, including diagnostic tests recommended in the European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PGP, and a neurological examination of the lower extremities. [7]

Sequence of stability and pain provocation tests for PGPActive straight leg raise The test is performed with the patient in a supine position with a straight leg and the feet 20 cm apart. The test is performed after the instruction ‘try to raise your legs, one after the other, above the couch for 20 cm without bending the knee’.

The patient is asked to score impairment on a 6–point scale:not difficult at all = 0;

minimally difficult = 1;

somewhat difficult; difficult = 2;

fairly difficult = 3;

very difficult = 4;

unable to do = 5.The scores on both sides are added, so that the total score range from 0 to 10.9

Gaenslen’s test The patient, lying supine, flexes the knee and hip of the same side, the thigh being crowded against the abdomen with the aid of both the patient’s hands clasped about the flexed knee. The patient is then brought well to the side of the table, and the opposite thigh is slowly hyperextended by the examiner with gradually increasing force by pressure of the examiner’s hand on top of the knee. With the opposite hand, the examiner assists the patient in fixing the lumbar spine and pelvis by applying pressure over the patient’s clasped hands. The test is positive if the patient experiences pain, either local or referred on the provoked side. [16]

Long dorsal sacroiliac ligament test The subject lies on her side with slight flexion in both the hip and knee joints. If the palpation causes pain that persists more than 5 s after removal of the examiner’s hand, it is recorded as pain. If the pain disappears within 5 s, it is recorded as tenderness. [17]

Modified Trendelenburg’s test The patient stands on one leg, and flexes the other at 90° in the hip and knee. If pain is experienced in the symphysis, the test is positive. [17]

Patrick’s FABER test The subject lies supine. One leg is flexed, abducted and externally rotated (FABER, abbreviation of flexion abduction and external rotation) so that the heel rests on the opposite knee. If pain is felt in the sacroiliac joints or in the symphysis, the test is considered positive. [17]

Posterior pelvic pain provocation test The test is performed with the woman supine and the hip flexed to an angle of 90° on the side to be examined: a light manual pressure is applied to the patient’s flexed knee along the longitudinal axis of the femur while the pelvis is stabilised by the examiner’s other hand resting on the patient’s contralateral superior anterior iliac spine. The test is positive when the patient feels a familiar well-localised pain deep in the gluteal area on the provoked side. A similar test is described as posterior shear or ‘thigh trust’. [17, 18]

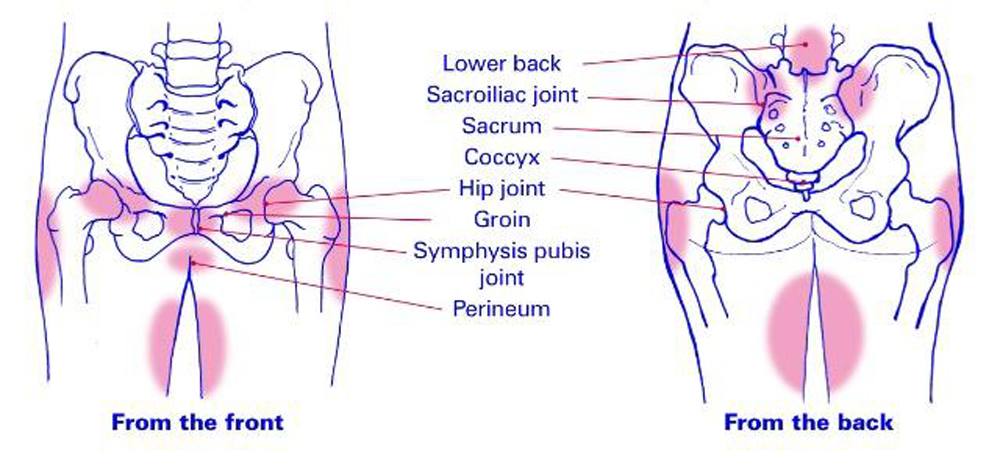

Symphysis palpation test The subject lies supine. The entire front side of the pubic symphysis is palpated gently. If the palpation causes pain that persists more than 5 s after removal of the examiner’s hand, it is recorded as pain. If the pain disappears within 5 s, it is recorded as tenderness. [17]A demographic questionnaire used in an earlier study on pelvic pain in pregnancy was filled in at baseline. [19] The women marked the pain location on drawings with the pelvis and the low back demarcated. Pain intensity was rated on a Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) from 0 to 100, where 0 meant ‘No pain’ and 100 ‘Unbearable pain’. Information on pain-related activities of daily living (ADL) was collected through the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), which at the time of the data collection was one of the principal outcome measures for defining disabling effects from spinal disorders and PGP. [7, 20] It is a patient-completed questionnaire which gives a subjective percentage score of the level of function (disability) in 10 ADLs in patients with low back pain. Every activity contains six statements on how it is performed. The statements are scored from 0 to 5, with the first statement scoring 0 through to the last at 5. The scores for all questions answered are summed, then multiplied by 2 to obtain the index (range 0–100). Zero is equated with no disability and 100 is the maximum disability possible.

Physical workload was measured through five answer categories ranging from ‘sedentary’ to ‘ heavy’, following a scale used in Stockholm Public Health questionnaire. [21] The question on job satisfaction was a bipolar 5–point Likert scale with increments in two opposite directions (‘Very bad’ and ‘Very good’) and a neutral point in the middle. [22]

Every Sunday the women were asked through a short message service (SMS) how many days the previous week they had experienced bothersome pelvic pain: ‘How many days during the previous week has your pelvic pain been bothersome, (ie, affected your daily activities or routines)?’ If there was no reply, the question was repeated 24 hours later. The question should be answered with one single number between 0 and 7. The response was automatically entered into a database, which collected the continuous information from each participant over the duration of the study.

Demographic descriptive data are presented as median values with IQRs for continuous variables, and as frequencies for categorical variables. For univariate comparisons between symptomatic and asymptomatic subgroups, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis statistics were used. Categorical predictors in our model were four groups following the outcome from the ASLR and P4 tests (1: P4 positive, 2: ASLR positive, 3: both P4 and ASLR positive, 4: ASLR and P4 negative), time (pregnancy week), and the interaction term between time and test group for investigating whether the trajectory of SMS-reported number of bothersome days differed between the test groups. Other predictors in the model were age, number of previous deliveries and body mass index (BMI) before pregnancy.

The longitudinal trajectory of the SMS-Track response was modelled using a generalised estimating equations (GEE) approach, extending the generalised linear model to correlated longitudinal data and clustered data within subjects. The within-subject dependencies resulting from repeated measurement were modelled assuming an autoregressive relationship in the working correlation matrix. As the outcome variable was count data (weekly number of bothersome days with pain), the Poisson distribution was assumed with a log-link function.

Data were analysed using SPSS V.22.0 software. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guideline was used during the writing of this article.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in developing the research questions, outcome measures, as well as in the design and conduct of the study, or in the recruitment of patients.

(P4) tests positive, compared with the estimate for women with both tests negative. Women with both tests positive were estimated with twice the amount of bothersome days per week (table 3). For women with either P4 or ASLR test positive and a lower incidence rate, the mean amount of bothersome days was lower, but still estimated as approximately 1.5 times higher than for women with both tests negative. For every pregnancy, the mean number of bothersome days increased by 13.5%. Even a slightly higher BMI had a significant impact on the mean amount of bothersome days. Age had no impact.

Results

Overall, 506 women agreed to participate in this study. Three were excluded due to incomplete data. On ultrasound examination in pregnancy week 18 did 42% (212/503) of the women report pain in the lumbopelvic region. A clinical examination revealed that 39% (196/503) of the women fulfilled the criteria for a probable PGP diagnosis, and 27% (137/503) showed positive response to ASLR and P4 tests. A further 12 women reported pelvic pain but did not respond to recommended clinical tests, and were therefore placed in the ‘ASLR and P4 tests negative group’.

There were significant differences in some demographic and clinical features at baseline between the women with and without pelvic pain and with different test outcomes (tables 1–2).

Women with positive P4 and ASLR tests experienced heavier workload. They also presented higher BMI at week 18, exercised less both before and during pregnancy, and slightly more than one-third reported feeling depressed during the pregnancy. Physical disability (ODI) and pain level (NRS) at week 18 were considerably higher in women with positive tests than in women reporting pain but having negative P4 and ASLR tests (table 2).

Women with a positive ASLR, but negative P4 test, had the highest number of previous pregnancies. Almost half of the women with both P4 and ASLR tests positive had been on sick leave during their pregnancy. Apart from the P4 and ASLR, the long dorsal ligament test showed the highest positive response rate, followed by the symphysis provocation test (table 2).

The SMS-Track response rate was 75% (2,148 responses to 2,877 sent messages). Due to a declining SMS-Track response at the end of the pregnancy, we stopped our SMS-Track analysis at week 38. A GEE analysis revealed that all entered variables, except ‘age’, were significant predictors for the number of days with bothersome pelvic pain, and there was a significant interaction between diagnostic group and time, implying that the time course of days with bothersome pelvic pain was different for the different test groups.

The estimated weekly mean number of days with bothersome pelvic pain for the different test groups is presented in figure 1. Women with both P4 and ASLR tests positive experienced from week 18 a high weekly mean number of days (H5) with bothersome pelvic pain throughout the pregnancy. Women with both tests negative showed a steadily rising number of bothersome days throughout the pregnancy, from 0.5 day in week 18, to 2 days in week 37. The group with a P4 positive and an ASLR negative test had approximately 3 days of bothersome pelvic pain in week 18, which was considerably lower than the group with both tests positive, but showed rapidly increasing number of days with pain. In week 29, the number of days with bothersome pelvic pain equalled that of the group with both tests positive, and thereafter matched this group. Women with a positive ASLR and a negative P4 test also showed 3 days of bothersome pelvic pain in week 18, but never reached the mean number of bothersome days reported by women with P4 and both tests positive.

The parameter estimates output showed the estimated rate for experiencing bothersome days to be 7.5 times higher in women with both active straight leg raise (ASLR) and posterior pelvic pain provocation

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the only study in which women with pelvic pain in pregnancy have been followed with SMS-Track. The main result of this study was that if both P4 and ASLR tests were positive in pregnancy week 18, a persistent pelvic pain of more than 5 days/ week throughout the remainder of pregnancy could be predicted. If either test was positive in week 18, a similar course was shown, but women with a positive P4 test revealed a more uncomfortable course than women with a positive ASLR test, who never reached the bothersome levels of the other groups. Robinson and coworkers23 reported a similar outcome for the P4 test in a prospective cohort study on the association between sociodemographics, psychological and clinical factors measured at mid-pregnancy, and disability and pain intensity at week 30. However, their data showed no significant association between the ASLR test result and the disability and pain intensity in pregnancy week 30.

Although women who had a positive ASLR test and negative P4 test at baseline presented a comparatively low mean number of bothersome days with pain, they also had the highest mean number of previous pregnancies and the highest mean rate of pelvic pain in previous pregnancies. Interestingly, our data also revealed that they exercised more frequently in comparison with women in the other positive test groups, both before and during the present pregnancy.

Interpretation

Since sufficient force closure of the sacroiliac joints requires appropriate muscular, ligamentous and fascial interaction, may women with pelvic pain in previous pregnancies have experienced that exercising improves muscle activation, recovers function and decreases pain. [24–26] Additionally, experiences of pain prevention and rehabilitation in previous pregnancies may work as an incitement to engage in physical activity and regular exercise, both before and during pregnancy.

Our analysis also revealed a significant difference between the test groups in women described feeling depressed, and that a prepregnancy BMI slightly higher than average had a significant impact on the mean number of bothersome days. Distress has previously been identified as a factor associated with a higher likelihood of PGP in pregnancy, as have a higher BMI and a higher gestational age. [27] One previous study found distress contributing to disability, but not to pain intensity. [23]

Nevertheless, some individuals seem to tolerate pain better, have less catastrophising tendencies and show more positive social response to pain, regardless of exposure to stressful circumstances and/or internal distress. [28] Finally, women with a possibility to control their own work situation have better health during pregnancy than women without such chances. As indicated in this study and confirmed in previous studies, most pregnant women benefit from exercise since it increases pain tolerance, improves or maintains physical fitness, helps with weight management, reduces the risk of gestational diabetes in obese women, and enhances psychological well-being. [29–32]

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the retrospectively collected information on pain in previous pregnancies and pain before pregnancy, which may produce biased results. Another limitation was found in the data collection via the SMS-Track system. In Norway, at the time of the study, there were more mobile phone service providers than in neighbouring countries, where SMS-Track studies previously had been successfully performed. Unfortunately, we had frequent problems reaching women through some of the providers. These problems led to data missing at random, but the GEE analytic approach may in these instances compensate for missing data. However, using the SMS-Track system in data collection is also a strength in our study, since it provides instant data on participants’ situation, and responses are immediately recorded in a datasheet, which minimises further data handling and risk of error.

Conclusion

If both active straight leg raise (ASLR) and P4 tests are positive at a clinical examination in mid-pregnancy, a course of persistent bothersome pelvic pain for more than 5 days per week throughout pregnancy may be predicted. The number of days per week with bothersome pelvic pain increases for every added pregnancy, but individual control over work situation and regular exercise may work as a PGP prophylactic since it invigorates a positive impact on optimal force closure of the pelvis, reduces risk of instability in the pelvic joints and enhances overall well-being.

Since there is still no gold standard for diagnosing pelvic girdle pain (PGP), particularly regarding the number of tests at the clinical examination, we recommend further research in this area, aiming at predictive, preventive and diagnostic measures for identifying women at risk of developing PGP in pregnancy. It would, for example, be interesting to see if women with a history of PGP have a higher pain-related anxiety and if it influences pain.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the midwives at Stavanger University Hospital for assistance in collecting the data.

Contributors

SM, IK, JPL, KA and IØ made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. SM and IK performed the data collection. SM, IK and AMG controlled the data. SM and KSB analysed the data. SM, JPL, KA, AMG, KSB and IØ made final approval of the version to be published. SM agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

The Norwegian Chiropractic Association ( kiropraktikk. no; Storgata, Oslo, Norway) funded the acquisition of an SMS-Track licence.

Competing interests

None declared.

References

Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, et al.

Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence.

Eur Spine J 2004;13:575–89.Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J.

Prognosis in four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic pain.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:505–10.Verstraete EH, Vanderstraeten G, Parewijck W.

Pelvic Girdle Pain during or after Pregnancy: a review of recent evidence and a clinical care path proposal.

Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2013;5:33–43.Gausel AM, Kjærmann I, Malmqvist S, et al.

Pelvic girdle pain 3-6 months after delivery in an unselected cohort of Norwegian women.

Eur Spine J 2016;25:1953–9.Malmqvist S, Kjaermann I, Andersen K, et al.

The association between pelvic girdle pain and sick leave during pregnancy; a retrospective study of a Norwegian population.

BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:237.Mens JM, Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, et al.

Understanding peripartum pelvic pain. Implications of a patient survey.

Spine 1996;21:1363–9.Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, et al.

European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain.

Eur Spine J 2008;17:794–819.Gutke A, Hansson ER, Zetherström G, et al.

Posterior pelvic pain provocation test is negative in patients with lumbar herniated discs.

Eur Spine J 2009;18:1008–12.Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, et al.

Reliability and validity of the active straight leg raise test in posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy.

Spine 2001;26:1167–71.Damen L, Buyruk HM, Güler-Uysal F, et al.

Pelvic pain during pregnancy is associated with asymmetric laxity of the sacroiliac joints.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001;80:1019–24.Gutke A, Kjellby-Wendt G, Oberg B.

The inter-rater reliability of a standardised classification system for pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain.

Man Ther 2010;15:13–18.Robinson HS, Mengshoel AM, Bjelland EK, et al.

Pelvic girdle pain, clinical tests and disability in late pregnancy.

Man Ther 2010;15:280–5.Axén I, Bodin L, Bergström G, et al.

The use of weekly text messaging over 6 months was a feasible method for monitoring the clinical course of low back pain in patients seeking chiropractic care.

J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:454–61.Christie A, Dagfinrud H, Dale Ø, et al.

Collection of patientreported outcomes;--text messages on mobile phones provide valid scores and high response rates.

BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:52.Kew S.

Text messaging: an innovative method of data collection in medical research.

BMC Res Notes 2010;3:342.Gaenslen FJ.

Sacro-iliac arthrodesis: indications, author's technic and end-results.

JAMA 1927;86:2031–5.Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J.

Evaluation of clinical tests used in classification procedures in pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain.

Eur Spine J 2000;9:161–6.Laslett M, Williams M.

The reliability of selected pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint pathology.

Spine 1994;19:1243–9.Malmqvist S, Kjaermann I, Andersen K, et al.

Prevalence of low back and pelvic pain during pregnancy in a Norwegian population.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2012;35:272–8.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB.

The oswestry disability index.

Spine 2000;25:2940–53.Leijon O, Wiktorin C, Härenstam A, et al.

MOA Research Group. Validity of a self-administered questionnaire for assessing physical work loads in a general population.

J Occup Environ Med 2002;44:724-35.Stats NZ.

Methodological standard for writing and constructing a questionnaire.

http://archive.stats.govt.nz/methods/survey-designdata-collection/

writing-questionnaire/structure.aspxRobinson HS, Veierød MB, Mengshoel AM, et al.

Pelvic girdle pain- -associations between risk factors in early pregnancy and disability or pain intensity in late pregnancy: a prospective cohort study.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:91.O'Sullivan PB, Beales DJ.

Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders--Part 1: a mechanism based approach within a biopsychosocial framework.

Man Ther 2007;12:86–97.Beales DJ, O'Sullivan PB, Briffa NK.

Motor control patterns during an active straight leg raise in chronic pelvic girdle pain subjects.

Spine 2009;34:861–70.Stuge B, Laerum E, Kirkesola G, et al.

The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial.

Spine 2004;29:351–9.Kovacs FM, Garcia E, Royuela A, et al.

Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy: a multicenter study conducted in the Spanish National Health Service.

Spine 2012;37:1516–33.Karoly P, Ruehlman LS.

Psychological "resilience" and its correlates in chronic pain: findings from a national community sample.

Pain 2006;123:90–7.Wergeland E, Strand K.

Work pace control and pregnancy health in a population-based sample of employed women in Norway.

Scand J Work Environ Health 1998;24:206–12.Owe KM, Bjelland EK, Stuge B, et al.

Exercise level before pregnancy and engaging in high-impact sports reduce the risk of pelvic girdle pain: a population-based cohort study of 39 184 women.

Br J Sports Med 2016;50:817–22.Andersen LK, Backhausen M, Hegaard HK, et al.

Physical exercise and pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy: A nested case-control study within the Danish National Birth Cohort.

Sex Reprod Healthc 2015;6:198–203.Anon.

Committee Opinion No. 650 Summary: Physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:1326–7.

Return to PEDIATRICS

Return to PREGNANCY AND CHIROPRACTIC

Since 7-29-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |