Efficacy of Chiropractic Manual Therapy on Infant Colic:

A Pragmatic Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled TrialThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012 (Oct); 35 (8): 600–607 ~ FULL TEXT

Joyce E. Miller, BS, DC, DABCO, David Newell, PhD, Jennifer E. Bolton, PhD

Associate Professor,

Anglo-European College of Chiropractic,

Bournemouth, UK.

jmiller@aecc.ac.uk.

Dr. Miller wrote a follow-up to this study, a cost comparison of the medical and chiropractic care provided in her earlier RTC study, titled:

Costs of Routine Care For Infant Colic in the UK and Costs of Chiropractic Manual Therapy

as a Management Strategy Alongside a RCT For This Condition

J Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 2013 (Jun); 14 (1): 1063–1069

This RTC cast new and significant insights into previous colic trials:

Chiropractic care lowered overall costs more than 400% compared with medical management

The current study revealed that excessively crying infants were 5 times less likely to cry significantly, if they were treated with chiropractic manual therapy, and that chiropractic care reduced their crying times by about 50%, compared with those infants provided solely medical management.

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of chiropractic manual therapy for infants with unexplained crying behavior and if there was any effect of parental reporting bias.

METHODS: Infants with unexplained persistent crying (infant colic) were recruited between October 2007 and November 2009 at a chiropractic teaching clinic in the United Kingdom. Infants younger than 8 weeks were randomized to 1 of 3 groups:(i) infant treated, parent aware;

(ii) infant treated, parent unaware; and

(iii) infant not treated, parent unaware.

The primary outcome was a daily crying diary completed by parents over a period of 10 days. Treatments were pragmatic, individualized to examination findings, and consisted of chiropractic manual therapy of the spine. Analysis of covariance was used to investigate differences between groups.

RESULTS: One hundred four patients were randomized. In parents blinded to treatment allocation, using 2 or less hours of crying per day to determine a clinically significant improvement in crying time, the increased odds of improvement in treated infants compared with those not receiving treatment were statistically significant at day 8 (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 8.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4-45.0) and at day 10 (adjusted OR, 11.8; 95% CI, 2.1-68.3). The number needed to treat was 3. In contrast, the odds of improvement in treated infants were not significantly different in blinded compared with nonblinded parents (adjusted ORs, 0.7 [95% CI, 0.2-2.0] and 0.5 [95% CI, 0.1-1.6] at days 8 and 10, respectively).

CONCLUSIONS: In this study, chiropractic manual therapy improved crying behavior in infants with colic. The findings showed that knowledge of treatment by the parent did not appear to contribute to the observed treatment effects in this study. Thus, it is unlikely that observed treatment effect is due to bias on the part of the reporting parent.

From the Article

Background

Excessive infant crying in otherwise healthy infants, traditionally called infant colic, continues to be an enigmatic condition with no known cause and no known cure. [1–3] Afflicting between 10% to 30% of all infants and consuming significant health care resources, [2] infant colic is a problem for parents and clinicians, both of whom try a wide range of therapies with often disappointing results.

Despite decades of research, a clear pathogenesis has not been elucidated. Notwithstanding, what is clear is that underlying disease is rare in the excessively crying baby [4] and that half of those affected recover by 6 months of age, [5] with a small proportion at risk of injury6 or long-term developmental problems. [7–9] In an effort to help their child with what appears to be a painful condition, some parents choose complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), including chiropractic manual therapy. [9–12] To date, several randomized trials have been reported, [13–19] and although these trials demonstrate some reduction in crying, weaknesses in study methodologies have compromised their contribution to the evidence base. [20–23]

A Danish study in 199913 showed manual therapy resulted in a significant reduction in crying in a 2–week trial when compared with simethicone (known to have no effect over placebo3) as a control. However, the parents were not blind to treatment allocation, which could have biased their reports of outcome. Similarly, a British study in 2006, comparing manual therapy with no treatment, showed significant declines in crying in the treatment group, but again, parents were not blind to the intervention received.14 In contrast, a Norwegian study in 2002, which did blind the parents to treatment allocation, showed similar reductions in crying with manual therapy and with placebo. [15] However, the manual therapy in that trial was an intervention nonspec0ific to the patient. A British study in 2005 compared 2 manual therapies, and although participants in both treatment arms showed reductions in crying, there was no placebo group for comparison. [16] Finally, 3 South African studies showed that significant improvements in crying with manual therapy over detuned ultrasound [17] and medication [18, 19], can only be found in conference proceedings and therefore remain unpublished in the peer-reviewed literature. Based on these studies, there is some but not conclusive evidence to make a recommendation of manual therapy for the excessively crying baby. [22] For there to be a better understanding about the efficacy of chiropractic treatment for infants with colic, these methodological weaknesses should be addressed.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to conduct a single-blind, randomized controlled trial comparing chiropractic manual therapy with no treatment and to determine whether parents' knowledge of treatment biases their report of change in infant crying.

The questions posed were as follows:(i) in colicky infants, is there a difference in crying time between infants who receive chiropractic manual therapy and those who do not, and

(ii) in colicky infants, is there a difference in infant crying time between parents blinded and parents not blinded to treatment?

Methods

Participants

Infants with unexplained persistent crying (infant colic) presenting to a chiropractic teaching clinic at the Anglo-European College of Chiropractic were recruited between October 2007 and November 2009. The “mother's diagnosis” of colic [24–26] was used to determine eligibility for the trial, verified by a baseline crying diary of 3 days or more. Other inclusion criteria were as follows: patients had to be younger than 8 weeks, born at a gestational age of 37 weeks or later, and had a birth weight of 2500 grams or more and show no signs of other conditions or illness. The parents of consecutively presenting infants fulfilling the inclusion criteria were informed of the study and gave written consent to participate. Parents completed a questionnaire (baseline) and were then randomized to 1 of 3 groups using permutated blocks of 18 and computer-generated allocations. These allocations were sealed in opaque and consecutively numbered envelopes and revealed to treating practitioners immediately before treatment proceeded. In 2 of the 3 groups, infants received treatment, and in the third, no treatment was administered. In 1 of the 2 treatment groups, the parent was able to observe the treatment and knew that the infant was being treated. In the other 2 groups, the parent was seated behind a screen and was not able to observe the infant. Thus, in these 2 groups, the parent was “blind” as to whether or not the infant was treated.

This resulted in 3 groups:(i) infant treated/parent aware (treated, not blinded, or T[NB]),

(ii) infant treated/parent unaware (treated, blinded, or T[B]), and

(iii) infant not treated/parent unaware (not treated, blinded, or NT[B]).Participating parents were not charged for treatment; those parents of infants in the no-treatment group were offered a series of free treatments at the end of the study period. There were no restrictions regarding medication or other health care use during the trial.

Parents were informed of the interventions in all 3 groups and gave informed consent to participate. The study received ethics approval from the Anglo-European College of Chiropractic Research Ethics Sub-Committee in September 2007. A research assistant was partially funded by the British Columbia Chiropractic Association. Tomy Toy Company donated a cuddly toy to each infant at exit of the trial.

Interventions

All treatments were administered by a chiropractic intern with an experienced chiropractic clinician in attendance. Treatments were pragmatic, individualized to examination findings of the individual infant, and consisted of chiropractic manual therapy of the spine. Specifically, this involved low force tactile pressure to spinal joints and paraspinal muscles where dysfunction was noted on palpation. The manual therapy, estimated at 2 N of force, was given at the area of involvement without rotation of the spine. The treatment period was up to 10 days, and the number of treatments during this period was informed by the examination findings and parent reports. Treatment was terminated if parents reported complete resolution of symptoms. Infants in the blinded groups were placed by the parent on the examination table. Thereafter, parents sat in the examination room but behind a screen so they were unable to observe the interaction between the practitioner and their child. Patients in the no-treatment group were not touched by the intern and/or clinician. The same scripted words were spoken by the practitioner for infants in all 3 groups and consisted of “We will begin treatment now; it will be just one more minute; that is the end of treatment; we will stop now.” Thus, although parents were informed of the treatment protocols in each of the 3 groups before randomization, the implication to all parents was that their child was being treated.

Outcome Measures

Parents were asked to complete a questionnaire concerning infant demographics at baseline. Starting at baseline, a 24–hour crying diary was completed throughout the study period ending either after 10 days or at discharge (whichever was sooner). Crying time extracted from the diary [26–28] was selected as the primary outcome measure a priori. Data extraction was conducted by an assessor blind to treatment group allocation. A global improvement scale (GIS) was completed at either 10 days or discharge. This scale rated the parent's impression of change in their child's condition since beginning the treatment (1, worse; 2, no change; 3, little improvement; 4, moderate improvement; 5, much improvement). Parents also reported on any adverse effects during the treatment period. To test blinding to treatment, at the end of the trial, parents blinded to treatment allocation were asked to guess whether or not their child had been treated. The options were “treated,” “not treated,” and “don't know.”

Sample Size

The trial was designed to have 80% power to detect a significant difference at the 5% level between the groups of at least 2–hour crying time at 10 days. [13] The SD at baseline was estimated to be 2.5. [13] Adding 20% for dropouts, we estimated that we needed at least 30 patients in each group.

Data Analysis

Analysis was performed per protocol. An intention-to-treat analysis was conducted. For continuous data (reported crying time), we compared the mean change in crying time from baseline to each time point between groups using analysis of covariance with age, sex, and the baseline 24–hour crying time as covariates.

Categorical data for improvement were calculated from both the GIS (score ≥4; moderate and much improvement) and from cutoff scores on the 24–hour crying diary.

We chose a priori either(i) 2 hours or less in a 24–hour period or

(ii) more than 30% reduction in crying time from baseline.From these, crude odds ratios and numbers needed to treat (NNT) and adjusted odds ratios using logistic regression were calculated.

Results

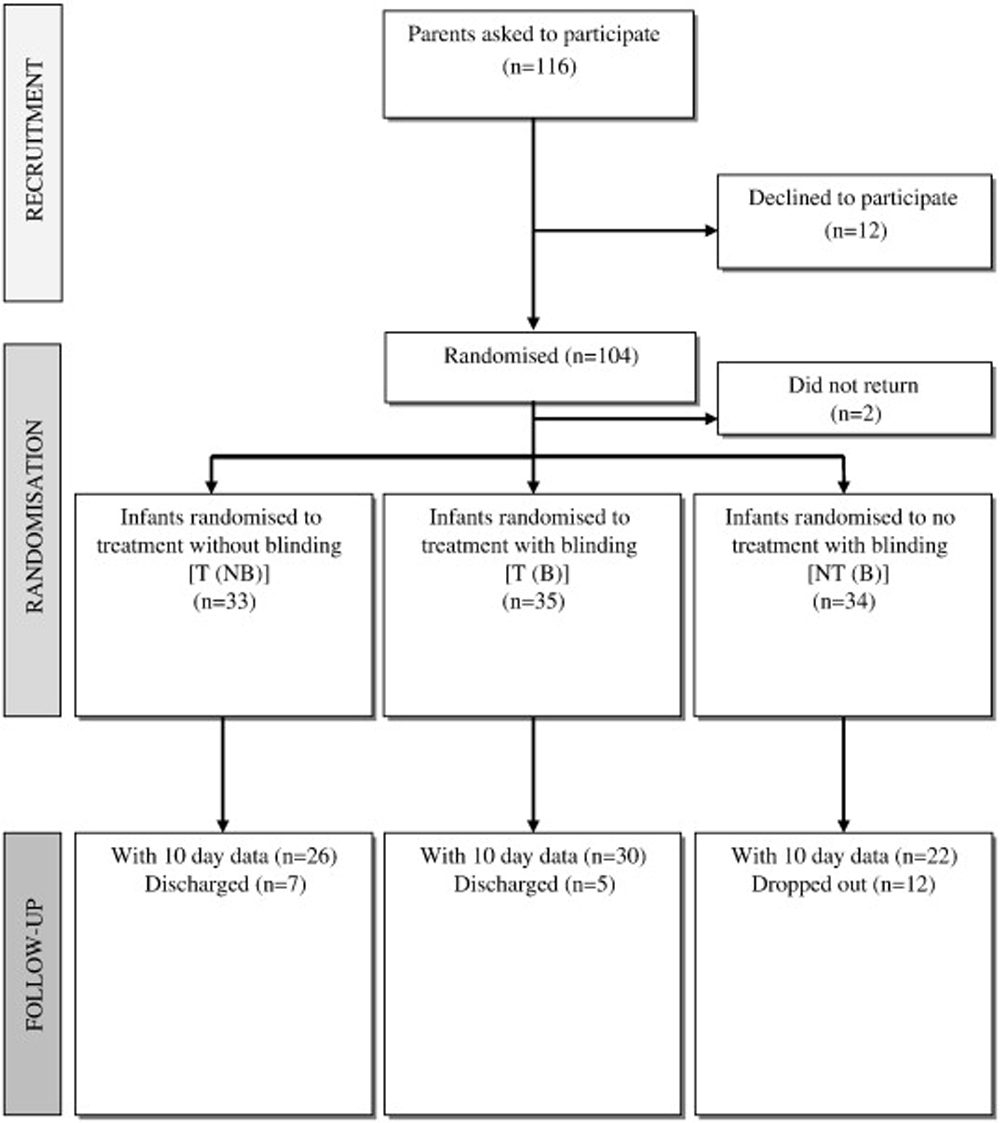

Figure 1

Table 1 Of 116 parents of eligible infants given information about the study, 104 were recruited and their children randomized to 1 of the 3 groups; the remaining 12 parents were unwilling to participate. Overrecruitment was considered appropriate because high dropouts have been noted in other trials. Two infants were not included in the final analysis: one due to sudden-onset illness and the other who did not return for treatment after recruitment. Data from the remaining 102 infants were analyzed, with 33 in the T(NB) group, 35 in the T(B) group, and 34 in the NT(B) group (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the 3 groups, except for sex, with a greater proportion of boys in the NT(B) group and girls in the T(B) group (Table 1). Sex has been shown to have no effect on infant colic in other studies.

By the end of the study period (10 days), 12 patients had dropped out in the no-treatment (NT[B]) group and 5 and 7 patients had been discharged in the blinded (T[B]) and not blinded treatment (T[NB]) groups, respectively. The numbers of dropouts and discharges are shown in Figure 1. At the end of the trial period or discharge (whichever was sooner), no adverse events were reported in any of the infants recruited to the study. One child in the nontreatment group reported an adverse effect of increased crying.

Of the 35 patients in the treatment group blinded to treatment allocation, 8 (22.9%) believed that their child was treated and 17 (48.6%) either did not know or believed that their child was not treated (there were 10 responses either missing or where the parent had given answers to 2 of the 3 options). Of the 34 patients in the no-treatment group blinded to treatment allocation, 5 (14.7%) believed that their child was not treated and 20 (58.8%) either did not know or believed that their child was treated (there were 9 responses either missing or where the parent had given answers to 2 of the 3 options).

Figure 2

Table 2 Figure 2 and Table 2 show the change in crying time from baseline values over the 10 days of the trial. The mean crying times within each of the 3 groups significantly decreased over time. Compared with baseline, by day 10, the mean decrease was 44.4% (P < .001), 51.2% (P < .001), and 18.6% (P < .05) in the treatment groups (T[B] and T[NB]) and the no-treatment (NT[B]) groups, respectively.

Comparison of treatment (T[B]) with no treatment (NT[B]) showed statistically significant differences in mean change in crying time from baseline at days 8 and 9 in favor of treatment. By day 10, the mean difference in the change in crying time from baseline between patients treated and not treated was 1.5 hours (Table 2).

In contrast, there were no statistically significant differences in the mean change in crying time from baseline at any of the time points between the patients of parents who were and were not blinded to treatment (Table 2). Table 2 also shows these differences in change scores where they were adjusted for age, sex, and baseline crying time. Entering these potential confounders into the analysis resulted in similar findings with a significant difference in change scores between the blinded treatment and the no-treatment groups from days 7 to 10, and again, no statistically significant differences in change scores at any time between the blinded and the nonblinded treatment groups were observed.

Table 3 To facilitate clinical interpretation of our findings, we categorized the change in crying time in terms of improvement. In this analysis, the odds of improvement (crude and adjusted for baseline crying time, age, sex) were calculated. Table 3 shows data obtained for improvement using both the GIS scale and the 2 cutoff values for the crying time data. In the adjusted analysis categorizing improvement using crying time scores, there were significantly greater odds of improvement with treatment (T[B]) compared with no treatment (NT[B]) at days 8 and using the criterion of 2 or less hours of crying per day, at day 10. This increase in odds of improvement at day 8 was 8 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4–45) and 5 (1.5–16), and at day 10, it was 12.0 (2.1–68) and 3 (0.8–9) using the cutoffs of 2 or less hours of crying per day and more than 30% change, respectively.

Using the GIS to categorize improvement at the end of the trial, there was a similar greater odds of improvement with treatment (T[B]) compared with no treatment (NT[B]). Although these results were statistically significant, the wide CIs reflecting the variability in the data and small sample sizes indicate the need for caution and the difficulty in precisely estimating any treatment effect in the target population. Notwithstanding, the NNT approximated 3 (Table 3), indicating that 3 infants need to be treated to gain one additional improvement in crying time over no treatment.

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of chiropractic manual therapy in infants with infantile colic and the effect that blinding has on the report of crying time by the parent. In previous studies, [13–19] any apparent effect that an intervention had on crying time in colicky infants has been challenged for lack of blinding of the parents and the consequential potential for reporting bias. In studies of interventions for excessive crying in infants, there is no alternative to the outcome being based on the parent's self-report of crying behavior, and although crying diaries in themselves have been shown to be valid measures, [27, 28] the influence of the parent knowing whether or not his/her child was treated raises suspicions, rightly or wrongly, about any observed treatment effect.

We attempted to overcome this impediment by purposively designing the trial to observe what, if any, effect the parent knowing about their child's treatment had on the report of crying time. The treatment was based on evidence that showed that such therapy has been implicated in reduced crying, and previous authors have hypothesized that colic is a musculoskeletal disorder. [13, 29, 30] Moderate finger pressure on irritable muscles has shown a relaxation response in adults, which included decreased heart rate and increased alpha and beta brainwave activity, which hallmark a relaxation response.30 A reduction in heart rate secondary to a therapeutic manual impulse at the suboccipital region has been similarly demonstrated in infants. [31] Other research corroborates the safety of the treatment found in this trial. [32]

In answer to our first question, the results of our study showed statistically significant differences in the change in crying time between infants receiving treatment and no treatment in parents blinded to treatment allocation and a greater odds of improvement in the treated group toward the end of the 10–day trial period. Although the results were not always statistically significant, the trend was for the treated infants to show a greater reduction in crying than those in the nontreated group within 2 to 3 days. This suggests that any beneficial effect of treatment is apparent early on thus quickly reassuring anxious and distressed parents. The question on group allocation posed at the end of the study suggests that the procedures taken to blind parents were reasonably successful, and the degree of blinding was not dissimilar between the treated and nontreated groups. When comparing the effects of parents blinded and not blinded to treatment, there were no significant differences in the reduction in crying, indicating that blinding the parent had no biasing effect on the report of infant crying behavior. Other studies [13, 14, 16–19 ]where the lack of parental blinding has been cited as a possible explanation for an observed treatment effect might therefore be reconsidered in the light of this finding.

The only other study15 in which parents were blinded reported no differences in effect between groups. Possible explanations for differences in the findings from this study and the one reported here include differences in treatment and control groups (their participants underwent motion palpation and holding/soothing, whereas our control group did not receive any clinical handling) and in the primary outcome measure. Moreover, it is likely that the study of Olafsdottir et al [15] included more infants at the severe end of the crying spectrum (as all had been previously treated unsuccessfully in the health care system), and the analysis did not account for the large dropout in the control group, which may have included the highest criers, as other studies show. [13, 33]

All dropouts in this study occurred in the no-treatment group, which has also been shown to be the case in other studies. [13, 33] Although the parents of these infants were apparently “blind” to the treatment group, we can speculate that any lack of improvement deterred parents from returning to the clinic. Alternatively, these parents may have correctly guessed that their child was not being treated and left the trial to be treated elsewhere. This is supported by our findings of no difference between the treatment groups in which parents were blinded and not blinded to treatment. We found a clinically significant effect of chiropractic manual therapy in this patient group but, importantly, that this is evident despite whether or not parents know their child was treated. We can conclude that any reporting bias by the parent was not responsible for the observed effect of treatment in this study.

A relatively low number of parents (n = 5 [15%]) reported that their child was not treated in the NTB group. It is also true that this was greater in the TB group, where 17 (49%) of the parents considered that either their child was not treated or they did not know. One reason for this is that we are, of course, not comparing like with like because the second is a composite figure. In addition, the 9 who dropped out in the NTB group might be assumed to have done so because their babies were not being treated. If this assumption were true, this would raise the number of patients who were not being treated to 14 (41%). When combined with the number of parents who did not know (20; 59%), this would bring the total to 100% compared with the 48% in the TB group, in line with what might be expected.

Limitations

This randomized trial did have limitations that caution interpretation of the findings, not least conducting a trial in a routine practice setting and the consequential problems of loss to follow-up. This was compounded by the fact that we decided, for ethical reasons, to discharge patients who were recovered early on in the trial.34 Together with small sample sizes from the outset and variability within our data sets, this meant that estimates of effects in the target population were imprecise, thus compromising, at least in part, their clinical use.

Although we paid particular attention to blinding the parents, it was not possible to exclude the parent from the treatment room altogether because of regulations governing chiropractic treatment for minors in the United Kingdom. Moreover, we only checked parents for blinding at the end of the study. By asking parents to state whether or not they thought their child was being treated, it was inevitable that any change in their child's condition by the end of the treatment period would have influenced their decision. Thus, we did not know the parents' “beliefs” day by day throughout the study period at times when they were completing the crying diary. Furthermore, as a single-blind trial, we only attempted to blind the parents. It was obviously not possible to blind those administering the treatment, and thus, the findings of this study may be subject to practitioner bias. The practitioners in this trial had no part in reporting outcomes from care.

External validity is often problematic in randomized trials, and this study is no exception. Infants were treated in an outpatient teaching clinic by different final-year student interns accompanied by experienced clinicians. This does not reflect treatment that is received in established chiropractic practices. Similarly, most parents were referred by general practitioners, midwives, and health visitors in the area, and in many cases, parents expected to pay for treatment. Whether our sample represents the population of parents of infants with excessive crying symptoms is therefore questionable. Moreover, the inclusion criterion that allowed for the mother's diagnosis of excessive crying is a subjective one, although paradoxically, this may increase the generalizability of the findings and all infants did fit the routine definition of colic for amount of crying previously shown in the research. [1–3, 25–29] Also, diary information and parental reporting of accurate time crying may be subject to recording error or bias.

Finally, we used 2 cutoffs in the change in crying time with which to categorize improvement in our participants. The more conservative of these was 2 or less hours per day of crying, which has been reported in the literature as a “normal” level of crying. [24, 35] The other cutoff of more than 30% reduction in crying was entirely arbitrary on our part and is open to challenge. However, we felt it necessary to define these end points to report the findings in clinically significant terms rather than as group mean statistically significant decreases in crying time that are more difficult to interpret from a clinical perspective. Both cutoff points were chosen for the practical reason to increase the robustness of the clinical results because cutoff points can be considered arbitrary. We did not mix the cutoff points but purposely kept them separate, to address any criticism concerning an idiosyncratic cutoff point.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this study demonstrate a greater decline in crying behavior in colicky infants treated with chiropractic manual therapy compared with infants who were not treated. The findings also showed that knowledge of treatment by the parent did not appear to contribute to the observed treatment effects in this study. Thus, it is unlikely that observed treatment effect is due to bias on the part of the reporting parent.

Funding Sources and Potential Conflicts of Interest

A research assistant was partially funded by the British Columbia Chiropractic Association. Tomy Toy Company donated a cuddly toy to each infant at exit of the trial. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

References:

Douglas P Hill P

Managing infants who cry excessively in the first few months of life.

BMJ. 2011; 343: d7772Morris S St James-Roberts I Sleep J Gillham P

Economic evaluation of strategies for managing crying and sleeping problems.

Arch Dis Child. 2001; 84: 15-19Lucassen P

Colic in infants.

Clin Evid. 2010; 02: 309Freedman SB Al-Harthy N Thull-Freedman J

The crying infant: diagnostic testing and frequency of serious underlying disease.

Pediatrics. 2009; 123: 841-848Crotteau CA Wight ST Eglash A

Clinical inquiries. What is the best treatment for infant colic?

J Fam Pract. 2006; 55: 634-636Reijneveld SA van der Wal MF Brugman E Hira Sing RA Verloove-Vanhorick SP

Infant crying and abuse.

Lancet. 2004; 364: 1340-1342Savino F Castagno E Bretto R Brondello C Palumeri E Oggero R

A prospective 10-year study of children who had severe infantile colic.

Acta Paeditry Suppl. 2005; 94: 129-132Wolke D Rizzo P Woods S

Persistent infant crying and hyperactivity problems in middle childhood.

Pediatrics. 2002; 109: 1054-1060Miller JE and Phillips HL.

Long-Term Effects of Infant Colic: A Survey Comparison of Chiropractic Treatment and Nontreatment Groups

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009 (Oct); 32 (8): 635–638Hestbaek L, Jørgensen A, Hartvigsen J.

A Description of Children and Adolescents in Danish Chiropractic Practice: Results from a Nationwide Survey

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Oct); 32 (8): 607–615Kemper KJ, Vohra S, Walls R.

The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Pediatrics

Pediatrics. 2008 (Dec); 122 (6): 1374-1386Barnes PM , Bloom B , Nahin RL:

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children:

United States, 2007

US Department of Health and Human Services,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, 2008.Wiberg, JM, Nordsteen, J, and Nilsson, N.

The Short-term Effect of Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Infantile Colic:

A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial with a Blinded Observer

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1999 (Oct); 22 (8): 517–522Hayden C Mullinger B

A preliminary assessment of the impact of cranial osteopathy for the relief of infant colic.

Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2006; 12: 83-90Olafsdottir E Forshei S Fluge G Markestad T

Randomized controlled trial of infant colic treated with chiropractic spinal manipulation.

Arch Dis Child. 2001; 84: 138-141Browning M Miller J

Comparison of short-term effects of chiropractic spinal manipulation and occipito-sacral decompression

in the treatment of infant colic: a single-blinded randomised comparison trial.

Clin Chiropr. 2008; 11: 122-129Koonin SD Karpelowsky AS Yelverton CJ Rubens BN

A comparative study to determine the efficacy of chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy

and allopathic medication in the treatment of infantile colic [].

in: World Federation of Chiropractic 7th Biennial Congress.

World Federation of Chiropractic, Orlando, FL2002: 18Mercer C Nook BC

The efficacy of chiropractic spinal adjustments as a treatment protocol in the management of infantile colic.

in: Haldeman S Murphy B 5th Biennial Congress of the World Federation of Chiropractic.

World Federation of Chiropractic, Auckland1999: 170-171Karpelowsky AS.

The efficacy of chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy in the treatment of infantile colic.

MSc Dissertation. Health Sciences,

Technikon Witwatersrand. Johannesburg, 2004.Ernst E

Chiropractic spinal manipulation for infant colic: a systematic review of randomised trials.

Int J Clin Pract. 2009; 63: 1351-1353Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leiniger B, Triano J.

Effectiveness of Manual Therapies: The UK Evidence Report

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Feb 25); 18 (1): 3Husereau D, Clifford T, Aker P, Leduc D, Mensinkai S.

Spinal Manipulation for Infantile Colic

Ottawa: Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment; 2003.

Technology report no 42Volkening DA

The short-term effect of spinal manipulation in the treatment of infantile colic:

a randomized controlled clinical trial with a blinded observer.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000; 23: 365Canivet C Hagander B Jakobsson I Lanke J

Infantile colic-less common than previously estimated?

Acta Paediatr. 1996; 85: 454-458Pauli-Pott U Becker K Mertesacker T Beckmann D

Infants with “colic”—mothers' perspectives on the crying problem.

J Psychosom Res. 2000; 48: 125-132Barr RG Rotman A Yaremko J Leduc D Francoeur TE

The crying of infants with colic: a controlled empirical description.

Pediatrics. 1992; 90: 14-21St. James-Roberts I Hurry H Bowyer J

Objective confirmation of crying durations in infants referred for excessive crying.

Arch Dis Child. 1993; 68: 82-84Barr RG Kramer MS Boisjoly C McVey-White L Pless IB

Parental diary of infant cry and fuss behaviour.

Arch Dis Child. 1988; 63: 380-387Wiberg K, Wiberg J.

A Retrospective Study of Chiropractic Treatment of 276 Danish Infants With Infantile Colic

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010 (Sep); 33 (7): 536–541Diego MA Field T Sanders C Hernandez-Reif M

Massage therapy of moderate and light pressure and vibrator effects on EEG and heart rate.

Int J Neurosci. 2004; 114: 31-45Koch LE Koch H Graumann-Brunt S Stolle D Ramirez J-M Saternus K-S

Heart rate changes in response to mild mechanical irritation of the high cervical spinal cord in infants.

Forensic Sci Int. 2002; 128: 168-176Miller, JE and Benfield, K.

Adverse Effects of Spinal Manipulative Therapy in Children Younger Than 3 Years:

A Retrospective Study in a Chiropractic Teaching Clinic

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 (Jul); 31 (6): 419–423McRury JM Zolotor AJ

A randomized controlled trial of a behavioural intervention to reduce crying among infants.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2010; 23: 315-322Hawk, C, Schneider, M, Ferrance, RJ, Hewitt, E, Van Loon, M, and Tanis, L.

Best Practices Recommendations for Chiropractic Care for Infants, Children, and Adolescents:

Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Oct); 32 (8): 639–647Clifford TJ Campbell K Speechley KN Gorodzinsky F

Sequelae of infant colic: evidence of transient infant distress and absence of lasting effects

on maternal mental health.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002; 156: 1183-1188

Return to PEDIATRICS

Return to CHIROPRACTIC AND COLIC

Since 10-18-2012

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |