Safety of Chiropractic Manual Therapy for Children:

How Are We Doing?This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 2009 (Dec); 10 (2): 655–660 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Joyce Miller, BSc, DC, DABCO, PhD

Anglo European College of Chiropractic, Lead Tutor, MSc

Advanced Practice Chiropractic Pediatrics,

Bournemouth University.Objectives: To assess the risk of adverse effects of chiropractic spinal manipulation in the pediatric population and to promote a culture of safety along with full reporting of adverse events in the chiropractic profession

Methods: Narrative review of all published reports of adverse effects of chiropractic pediatric spinal manipulation

Results: Adverse effects from chiropractic spinal manipulation are rare with 2 moderate and 4 severe events reported during a 59 year period with up to 30 million treatments estimated per year. Current reports show a very low rate (<1% in 8,290 treatments) of mild transient side effects lasting less than 24 hours.

Conclusion: Based on the published literature, chiropractic spinal manipulation, when performed by skilled chiropractors, provides very low risk of adverse effect to the pediatric patient. Vigilance to detect occult pathology as well as other steps to maintain safe practice are of utmost importance.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

When a child is presented for health care, safety is presumed by the parent, the family, the health care profession and society. Safety is the bedrock upon which all health care is based. After all, the first rule is, “Do no harm.” I once overheard a chiropractor say, “We cannot help everyone, but we don’t harm anyone.” Was that naïve, short-sighted or accurate? Chiropractors who once were secure that their practice was safe, may be currently feeling exposed. Safety for all patients is under scrutiny and the pediatric population is particularly vulnerable because they cannot speak for themselves. Further, parents are equally vulnerable as they are emotionally involved and may not be able to regulate their own stress let alone that of their child and may have difficulty making decisions for their child.

The clinician must take responsibility for the safety of the child under treatment. Safety is a chief concern in all of pediatric health care. [1] For example, the safety of medications given to children is increasingly considered an important public health issue. [2] In fact, such common remedies as cough and cold medications for children are no longer routinely recommended because of negative side effects. [3] The National Patient Safety Agency in the UK has tracked safety incidents in pediatric patients and reported many concerns. [4] Reviewing 33,446 reports on pediatric care in 2006, 19% experienced medication problems as well as other breaches of safety including 14% procedure problems, 9% errors in documentation and 7% errors in clinical assessment among other incidents. Of particular concern was the rate of medication error in children (19%) versus that in adults (9%). [4] The use of medication in children is common with a recent report that the majority of US children <12 years of age use one or more medications weekly.

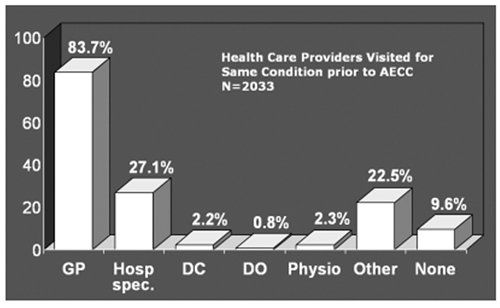

Figure 1 There is a trend showing that parents often seek complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for their children. [5] Chiropractic is the most common alternative care sought by parents for their child. [5, 6] Choosing a drug-free profession may reinforce the conjecture that parental choice of alternative care for their child may be partly due to “fear of pharma” or phobia related to the use of pharmacology, particularly glucocorticoids. [7] Safety is likely the main reason that parents turn to CAM therapies. [6] However, parents may seek a wide variety of practitioners and chiropractors may be just one of several clinicians treating a child. Data collection of 2,033 pediatric cases that presented to the Anglo-European College of Chiropractic (AECC) teaching clinic between 2000 and 2006 showed that over 90% had seen other clinicians and most had seen multiple types of practitioners for the same condition. (Figure 1)

Awareness of the care that other practitioners provide may be a factor in risk reduction. Certainly, this has been noted in the medical profession. McCann and Newell in 2006 registered concern that children treated by herbs and other ingested remedies could have a reaction because of the (unknown) combination with pharmaceuticals medically prescribed. [8] They further suggested that the complementary therapies (physical in nature such as massage and chiropractic) were less likely to interfere with biomedical treatment than complementary medicine which was ingested. Likewise, chiropractors must be aware of pharmaceuticals or other treatments undertaken by our patients which might cause side effects or otherwise complicate our therapy.

Review of safety in practice for the pediatric patient is common across health care. [9, 10] The goal of this article is to review the literature that investigated adverse events or side effects of chiropractic care for the pediatric patient and reflect upon risk reducing behaviours in our offices to improve safety for children under our care. The type of care most commonly provided by chiropractors is spinal manipulative therapy (SMT). Many chiropractors prefer the term “chiropractic adjustment”. For purposes of this article, we will use the term “SMT” with the understanding that it includes adjustment, manipulation and mobilization of the joints by a chiropractor. In the case of the children, we use the term pediatric spinal manipulative therapy (PSMT), to refer to procedures modified in terms of amplitude, force, speed and depth to the age-specific anatomy of the child relative to routine adult SMT. The safety of this type of care when delivered by chiropractors is the subject of this article.

Methods

A search was undertaken to locate relevant literature. Databases searched were PubMed, Scopus, Index to Chiropractic Literature, and Cochrane Library. Search restrictions were English language, human subjects. Publications were searched prior to September 2009. Hand searches followed through references and bibliographies of articles found. Search terms used were“chiropractic” AND “pediatric;”

“manipulation” AND “safety;” OR “side effects” OR “injury.”

Note the use of the Boolean Operators AND and ORThe pediatric age group was defined as between 0 and 16 years.

Results

Table 1 Twelve published reports addressed safety of manual therapy for the pediatric patient. Six reports were duplicates. Table 1 is a review of the literature that addresses safety of chiropractic treatment for the pediatric patient. One was a systematic review, one was described as a quasi-meta-analysis, one a retrospective records review, one a survey and two were case series.

Side effects can be divided into three categories:mild (transient and requiring no healthcare),

moderate (requiring additional health care) or

severe (requiring hospital care.

All three types of side effects were reported in the literature.

Mild side effects secondary to chiropractic manipulation

Two fairly recent (since 2007) reports, [12, 13] one a survey of parental report and one a retrospective record review, of a total of 1,076 pediatric patients having 8,290 treatments resulted in less than 1% experiencing irritability, soreness or stiffness, all transient and requiring no additional care.

Mild side effects secondary to manipulation delivered by medical doctors

The rate of mild side effects was higher when manipulation was given by non-chiropractors. In Table 1, two citations report side effects from 600 children and 695 children, respectively, who were treated with “chiropractic therapy,” but manipulation was performed by medical doctors. [14, 15] These are included because they specifically describe treatment as chiropractic therapy, although it was not delivered by chiropractors. In the first instance, there were no negative side effects and in the second, there were effects of bradycardia, flush and apnea, all of which subsided in 6-13 seconds. Two points need to be made;(1) the “chiropractic” adjustments given to these infants were described as ranging between 30 and 70 Newtons (N) with an average of 50 N.

(2) these side effects occurred preferentially (significance 0.0017) in the youngest age group (<3 months).These side effects would be considered as mild (transient) and occurred at a rate of 6% (84 out of 1,295 children) when combining both reports. It should be noted that this report regarded these as routine by-products of treatment rather than negative side effects.

Moderate side effects secondary to chiropractic manipulation

Two moderate cases were reported which involved severe headache and stiff neck and acute lumbar pain. These were treatments given by chiropractic students as part of a clinical trial. [11]

Severe side effects secondary to chiropractic manipulation

There were 4 citations in the systematic review which resulted in severe side effects from chiropractic care of pediatric patients. [11]

In a 1978 case, a 7 year old child had had repeated trauma from mid-air somersaults landing on his cervical spine and occiput. The “chiropractor diagnosed cervical misalignment and initiated a course of rapid manual rotations of the head from side to side with flexion and hyperextention.” [17] The child became ill with vomiting, severe headache and facial weakness. A visit to a neurologist found no abnormalities and chiropractic treatment was resumed, first with low back treatment and after two weeks, cervical adjusting. The child experienced two weeks of vomiting, headache and diplopia before hospital admission. Traumatic thrombosis of the left vertebral artery was suspected to be the source of “recurrent microemboli producing left facial paralysis, vomiting and diplopia.” [17] After two weeks the child was released from hospital and experienced persistent right-sided dysmetria with reduced quadrantanopia (blindness in visual field) as long term effects.

In 1992 a chiropractic manipulation to a 4-month baby with torticollis had a serious long-term effect resulting in quadriplegia regressing to paraplegia [18] months after treatment. [11] This occurred because infiltration of an astrocytoma was unknown at the time of initial treatment. The authors called for x-ray of every child with torticollis prior to manipulation. [18]

Another severe event occurred in 1983 with manipulation of a 12-year-old with osteogenesis imperfecta (a condition in which manipulation is contra-indicated) resulting in paraplegia. [11]

Chiropractic treatment in 1959 of a 12-year-old girl for neck pain persisting from congenital torticollis resulted in unsteady gait, decreased coordination, drowsiness and neck pain and hospitalization followed treatment. [11] Congenital occipitalization was diagnosed in hospital.

Indirect adverse effects of treatment such as missed diagnosis and/or delayed medical treatment were also reported in the Vohra review [11, 19] Nineteen cases were reported over a 57 year time span (1940-1997). [11] Sixteen cases involved delayed treatment and no serious adverse results occurred. These 16 cases were reported between 1992 and 1997. Three cases which developed serious adverse events occurred between 1940 and 1969.

Discussion

Overall, the published evidence does not suggest that chiropractic care for the pediatric patient is high risk. The most thorough systematic review [11] uncovered only 8 incidents of hurt or harm to children due to chiropractic manipulation in a 59-year time span (1940-1999) when billions of such treatments were given. The number needed to harm (NNH) has been calculated at one major neurovascular harm for every 250 million treatments. [16]

Any adverse event is regrettable and provides lessons to be learned. There appears to be a pattern wherein early cases (as long as 70 years ago) had worse outcomes than more recent cases. This may indicate that some enlightenment has occurred in our profession over the years. No longer are patients treated in a vacuum but are referred when it is clear that our care is not efficacious. Chiropractors are conscious that therapy must be effective prior to the natural decline of the disorder. Children usually respond quickly and generally do not require a course of treatment to extend beyond 2-3 weeks unless complicating factors are present. It is important that the treatment shows evidence of improved outcomes in that time span. If progress is not seen after 3 weeks of care, the clinician must reflect on the clinical usefulness of the approach and either modify the treatment plan or refer the patient for consultation with an appropriate specialist, The modern chiropractor is trained in recognition of red flags and differential diagnosis and this is reflected in fewer adverse events since 1992.

There are clearly gaps in the data set with few studies of patient safety or adverse effects of chiropractic care. This may be a result of under-reporting. Adverse effects should be reported as a part of normal routine. [20] Further, randomised trials are not a fruitful source of such data. There are few randomised trials addressing chiropractic treatment of the pediatric patient and only rarely do they address safety issues. The lack of safety reporting from RCTs is typical across medical research. [21] The lack of safety research in its own right is typical in much of health care. Over half of pharmaceutical interventions for pediatric patients are off-label or unlicensed. [22] It is possible that there is a different standard in allopathic reporting of side effects than there is in chiropractic reporting. For example, in the Koch study, 12.1% of the infants experienced bradycardia, flush and apnea after a medical manipulation. [14] In the report, these were not regarded as negative side effects, but merely an adaptation of the autonomic nervous system to manual therapy. These would arguably be interpreted as adverse side effects if occurring after treatment by a chiropractor. It should be noted that manipulation given to these infants was much higher force (30-70 N) than is recommended by the chiropractic profession.

What is implicit in safe practice is the ability to identify risk and to modify treatment taking that risk into account. There are too few incidents reported to ascertain where safety incidents cluster. That said, virtually all of the severe sequelae from mis-diagnosis or treatment stemmed from the lack of recognition of occult pathology. Non-recognition of pathology in a child increases the risk of a breach in safety under our care, as the child will be less resilient, as well as the fact that our care is inappropriate. It goes without saying that vigilance is required to detect occult pathology in every patient, although red flags may be more easily detected in adults who can speak for themselves and describe symptoms than in children.

The busy chiropractor may have questions:“How should I interpret this evidence for my practice?

Should I be concerned about the few incidents which have occurred?

How can I lower the risk of adverse events in this patient group in my own practice?”

Table 2 Chiropractors can look at practice through risk-reducing lenses and keep in mind some key points.

Know your limits. This is one of the keys of the Hippocratic Oath. Do not practice beyond your capabilities.

Continue to update skills in examination, treatment, note taking, communication, equipment, resuscitation and pediatric life support.

Do a thorough history and examination. Collect sufficient data to enable you to make a cogent decision on risk reduction.

Identify red flags and refer whenever indicated. [22]

Patients with co-morbidities or medical needs should be co-managed with the appropriate health professional.

Always take vital signs before any treatment commences.

Always use risk/benefit ratio and risk/effectiveness ratios to determine appropriateness of care (Table 2). [23-26] If the condition being treated does not have a clear efficacious therapy, do a therapeutic trial with a short course of treatment to determine whether benefits accrue more quickly than the natural history of the disorder. [26]

Use the correct technique for the age and condition of the patient as outlined in best practice recommendations. [23]

Promote and support research.

Report side effects and safety incidents so that data can be collected prospectively. [27]

Prospective reporting of all patient safety incidents is recommended and available. In the UK, the Chiropractic Patient Incident Reporting and Learning Systems (CPIRLS) [27, 28] is an on-line anonymous web-based system which accepts all types of patient safety events including errors, accidents, mishaps, near-misses or any deviation from the norm. The anonymity and security of the system encourages reporting from all chiropractors. This will result in accurate reporting of incidents for patients and learning and feedback for the profession.

Conclusion

Based on the published literature, it appears that manipulation, when given by a skilled chiropractor with years of training carried out with low forces recommended for pediatric care, has few side effects in the healthy infant and child and their recorded incidence is exceedingly low.

Nothing is of greater importance in our pediatric practice than taking a pro-active stance to incorporate safe practice strategies into daily practice and to report any incidents with the goal of safety and protection for all patients.

References:

Stephenson T.

Improving patient safety in paediatrics and child health.

Arch Dis Child 2008; 93(8):650-654.Vernacchio L, Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Mitchell AA.

Medication use among children <12 years of age in the United States: results from the Slone survey.

Pediatrics 2009; 124(2): 446-454.Sharfstein JM, North M, Serwint JR.

Over the counter but no longer under the radar: Pediatric cough and cold medications.

N Engl J Med 2007; 357(23):2321-2324.Stephenson TJ.

The National Patient Safety Agency.

Arch Dis Child 2005;90: 226-228.Kemper KJ, Vohra S, Walls R,

The Task Force on Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the Provisional Section on Complementary, Holistic and Integrative Medicine. The use of complementary and alternative medicine in paediatrics.

American Academy of Pediatrics 2008;122(6): 1374-1386.American Academy of Pedaitrics.

Palliative care for children.

Pediatrics. 2000;106:351-357.Hon K-LE, Kam W-YC, Leung T-F, Lam M-CA, Wong K-Y,

Lee K-CK, Luk N-MT, Fox T-F, Ng P-C.

Steroid fears in children with eczema.

Acta Paediatrica, 2006; 95(11): 1451-1455.McCann LJ and Newell SJ.

Survey of paediatric complementary and alternative medicine in health and chronic disease.

Arch Dis Child 2006; 91:173-174.Shaw KN, Ruddy RM, Olsen CS, Lillis KA,

Mahajan PV, Dean JM and Chamberlain JM.

Pediatric patient safety in emergency departments: unit characteristics and staff perceptions.

Pediatrics 2009; 124 (2): 485-493.Ventegodt S and Merick J.

A review of side effects and adverse events of non-drug medicine and clinical holistic medicine.

J Compl and Integerative Med 2009; 6(1):16.Vohra, S, Johnston, BC, Cramer, K, and Humphreys, K.

Adverse Events Associated with Pediatric Spinal Manipulation: A Systematic Review

Pediatrics. 2007 (Jan); 119 (1): e275–e283Miller JE and Benfield K.

Adverse Effects of Spinal Manipulative Therapy in Children Younger Than 3 Years:

A Retrospective Study in a Chiropractic Teaching Clinic

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 (Jul); 31 (6): 419–423Alcantara J, Ohm J, Kunz D.

Treatment-related aggravations, complications and improvements attributed to chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy of paediatric patients: a survey of parents.

Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies 2007 12 (Supplement 1):4.Koch LE, Koch H, Graumann-Brunt S, Stolle D, Ramirez J.-M, Saternus K.-S.

Heart rate changes in response to mild mechanical irritation of the high cervical spinal cord region in infants.

Forensic Science Intl 2002; 128:168-176.Biedermann H.

Kinnematic imbalance due to suboccipital strain in newborns,

J Manual Medicine 1992;6:151-156.Pistolese RA.

Risk Assessment of Neurological and/or Vertebrobasilar Complications

in the Pediatric Chiropractic Patient

J Vertebral Subluxation Research 1998; 2 (2): 73–78Zimmerman AW, Kumar AJ, Gadoth N, Hodges FJ 3rd.

Traumatic vertebrobasilar occlusive disease in childhood.

Neurology 1978;28:185-188.Shafir Y and Kaufman BA.

Quadraplegia after chiropractic manipulation in an infant with congenital torticollis caused by a spinal cord astrocytoma.

J of Pediatrics 1992;120(2):266-269.Lee AC, LI DH, Kemper KJ.

Chiropractic Care for Children

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000 (Apr); 154 (4): 401–407Hawk C, Khorsan R, Lisi A, Ferrance RJ, Evans MW.

Chiropractic Care for Nonmusculoskeletal Conditions: A Systematic Review

with Implications For Whole Systems Research

J Alternative Complementary Med 2007 (Jun); 13 (5): 491–512Ioannidis JPA, Lau J.

Completeness of safety reporting in randomized trials. An evaluation of 7 medical areas.

JAMA 2001; 285(4): 437-443.Conroy, SM, Choonara I, Impicciatore P, Mohn, Arnel H. et.al.

Survey of unlicensed and off-label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries.

BMJ 2000; 320: 79-82.Hawk C, Schneider M, Ferrance R, Hewitt E, Van Loon M, Tanis L.

Best Practices Recommendations for Chiropractic Care for Infants,

Children, and Adolescents: Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Oct); 32 (8): 639–647Cohen MH, Kemper KJ, Stevens L, Hashimoto D, Gilmour J.

Pediatric use of complementary therapies: ethical and policy choices.

Pediatrics 2005; 116(4): e568-575.Cohen MH and Kemper KJ.

Complementary therapies in pediatrics: a legal perspective.

Pediatrics 2005; 115(3): 774-780.Miller J.

Cry Babies: A Framework For Chiropractic Care

Clinical Chiropractic 2007 (Dec); 10 (3): 139–146Thiel H and Bolton J.

The reporting of patient safety incidents — first experiences with the chiropractic reporting and learning system (CRLS): a pilot study.

Clin Chiropractic 2006; 9:139-149.www.cpirls.org

Return to PEDIATRICS

Return to ADVERSE EVENTS

Since 2-06-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |