A Six-item Short-form Survey for

Measuring Headache Impact:

The HIT-6This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Quality of Life Research 2003 (Dec); 12 (8): 963–794 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS M Kosinski, M S Bayliss, J B Bjorner, J E Ware Jr, W H Garber, A Batenhorst, R Cady, C G H Dahlöf, A Dowson, S Tepper

Mark Kosinski,

QualityMetric Incorporated,

640 George Washington Highway,

Lincoln, RI 02865, USA

Background: Migraine and other severe headaches can cause suffering and reduce functioning and productivity. Patients are the best source of information about such impact.

Objective: To develop a new short form (HIT-6) for assessing the impact of headaches that has broad content coverage but is brief as well as reliable and valid enough to use in screening and monitoring patients in clinical research and practice.

Methods: HIT-6 items were selected from an existing item pool of 54 items and from 35 items suggested by clinicians. Items were selected and modified based on content validity, item response theory (IRT) information functions, item internal consistency, distributions of scores, clinical validity, and linguistic analyses. The HIT-6 was evaluated in an Internet-based survey of headache sufferers (n = 1,103) who were members of America Online (AOL). After 14 days, 540 participated in a follow-up survey.

Results: HIT-6 covers six content categories represented in widely used surveys of headache impact. Internal consistency, alternate forms, and test-retest reliability estimates of HIT-6 were 0.89, 0.90, and 0.80, respectively. Individual patient score confidence intervals (95%) of app. +/–5 were observed for 88% of all respondents. In tests of validity in discriminating across diagnostic and headache severity groups, relative validity (RV) coefficients of 0.82 and 1.00 were observed for HIT–6, in comparison with the Total Score. Patient–level classifications based in HIT–6 were accurate 88.7% of the time at the recommended cut–off score for a probability of migraine diagnosis. HIT–6 was responsive to self–reported changes in headache impact.

Conclusions: The IRT model estimated for a 'pool' of items from widely used measures of headache impact was useful in constructing an efficient, reliable, and valid 'static' short form (HIT–6) for use in screening and monitoring patient outcomes.

Keywords: Headache impact, Headache impact test (HIT™), Health–related quality of life (HRQOL), HIT–6, HIT, Item response theory (IRT), Migraine, Reliability, Validation

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Headache disorders are highly prevalent and can be severely disabling. [1, 2] Essential to research and the clinical management of headache and migraine is a method for standardizing the information gathered from patients about the impact on the patient’s life. Over the past decade there has been a proliferation of standardized questionnaires that measure the impact of headache or migraine on functional status and well–being. To be most useful in clinical practice and research, questionnaires that measure the impact of headache or migraine should meet psychometric and clinical criteria for reliable and valid measurement. To be practical these questionnaires must also be short. However, short form surveys currently used to evaluate the impact of headache or migraine on patient functioning are restricted in the range of measurement, focusing on extreme disability, which are not relevant for everybody. [3]

Furthermore, short form surveys that measure a limited range are not useful in measuring improvement because of problems with ceiling effects and they typically lack the measurement precision for making decisions at the level of the individual patient. [3] One solution to these problems is to develop short form surveys that are tailored to each patient’s level of functioning. The Internet–based headache impact test (DynHA™ HIT™), a computerized adaptive questionnaire, has demonstrated evidence of precision, reliability, validity, and clinical relevance in the measurement of headache impact. [3] However, since practical barriers still exist in using the Internet, particularly at the point of care, it became obvious that a brief paper and pencil version of HIT was needed that would meet accepted standards of reliability and validity and maintain comparability to the Internet–based HIT.

The challenge was to develop a paper and pencil version of HIT brief enough to be practical, yet long enough to comprehensively measure a wide range of headache impact and cover all the content areas included in the total item pool that captures the clinical, personal and socially relevant effects of headache. To meet this objective we took a three–pronged approach to developing the HIT short form, taking into account psychometric evidence, clinical relevance, and linguistic translation of the items selected from the item pool for the short form. This approach was carried out in independent development and validation phases.The purpose of this paper is to provide a brief account of the development phase of HIT–6 and focus primarily on the validation phase.

The objectives of the validation phase were to(1) calibrate the final version of the items in HIT–6 to the total HIT item pool,

(2) develop scoring algorithms to place the HIT–6 scores on the same scale as scored from the total HIT item pool,

(3) evaluate the test–retest, alternate forms and internal consistency reliability of HIT–6 scale scores,

(4) evaluate the construct validity of the HIT–6 scale,

(5) test the clinical validity of HIT–6 scale scores in relation to headache severity and migraine diagnosis, and

(6) test the responsiveness of HIT–6 scale scores in relation to self–reported changes in headache impact.

Methods

Development of HIT–6Psychometric relevance The starting point for selecting the HIT–6 items was the 54 items in the HIT item pool previously analyzed by IRT methods. [3, 4] IRT information functions and content validity were considered in selecting a subset of items for a fixed–length survey of headache impact. Using data from the National Survey of Headache Impact (NSHI) the best candidate items were evaluated on the basis of IRT information functions and content validity (in relation to widely used surveys and clinician judgment). Information functions express the contribution of each item to the overall test precision for various levels of headache impact. We selected a subset of 10 candidate items with IRT information functions that spanned a wide range of headache impact defined by the entire item pool, where more than 90% of recent headache sufferers scored. These 10 items also represented the six main content areas covered in widely used surveys (pain, social functioning, role functioning, vitality, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress).

Clinical relevance The next phase of development consisted of an independent review of the 10 candidate items by a panel of clinicians involved in the treatment of migraine headaches. The panel of clinicians recommended 35 newly developed items to be considered for the short form. Many of these suggested items covered similar content areas as captured by the original 10 candidate items, except that they were worded differently. Some of the suggested items covered content areas not captured by the original 10 candidate items and were regarded as clinically useful in gauging the severity of migraine during a typical physicianpatient interview. For example, one of the new items asked the patient ‘When you have a headache, how much of the time do you wish you could lie down?’

A survey was fielded by telephone interview (n = 459) and over the Internet (n = 601) that included the original 10 candidate items and the additional 35 items suggested by the panel of clinicians. Participants for the telephone survey were sampled from a prescription database and had a prescription for migraine medication during the previous year. Otherwise the design of this study was the same as the previous study (NSHI) used to develop the HIT item pool. We evaluated whether the additional items contributed to filling in measurement gaps and/or extended the range of impact defined by the original 10 candidate items. In addition, based on the self–assessment of headache severity, the frequency of migraine symptoms, and work loss productivity, we were able to also evaluate the clinical validity of each item. From this study, six items were selected to be included in the new HIT short form (HIT–6). Four of the HIT–6 items came from the original 10 and two came from the items suggested by the clinicians. These six items covered the six content areas represented in the total HIT item pool, covered more than 50% of the range of headache impact measured by the total item pool, and were among the most valid items in discriminant validity tests involving criterion measures of headache severity, frequency of migraine symptoms and work loss productivity.

Linguistic translation The final phase in the development of the HIT–6 short form consisted of a linguistic translation of the six items into 27 languages. The translation of HIT–6 items followed the same methodology used to translate the SF–36 Health Survey, including forward and backward translations of items and an independent review. [5] This translation process resulted in modifications to all HIT–6 items and response options. [6]

Validation of HIT-6Sample HIT-6 was validated using data compiled from a general population survey of recent headache sufferers collected via the Internet using AOL’s Opinion Place. Research on other health status questionnaires have found answers collected via the internet to be very similar to answers collected via paper and pencil. [7] AOL subscribers completed surveys by logging on to the AOL Opinion Place. Potential respondents entering Opinion Place were randomly assigned to one of many ongoing survey projects. Participants eligible for his study: (1) were aged 18–65 years of age, (2) had a headache in the past 4 weeks that was not due to a cold, flu, a head injury, or a hangover, (3) agreed to be contacted again in 2 weeks to complete another survey. Participants received AOL reward points as an incentive for participation.

Procedure At Time 1, the survey consisted of the HIT-6, computer adaptive administration of five items from the total HIT item pool (DynHA HIT), a battery of items on the frequency of six migraine symptoms, headache severity, the SF-8 Health Survey [7], and a number of new headache impact items (κ = 23) written by clinicians to enhance the total HIT item pool. The symptom and severity questions were based on a clinically validated, computer-assisted telephone interview used in previous studies [8, 9] and used in this study to validate the HIT-6. The SF-8 Health Survey was included in this study to evaluate the relationship between HIT-6 and generic measures of health status. DynHA HIT was included to evaluate alternative forms reliability of the HIT-6.

At Time 2, the questionnaire consisted of the HIT-6, DynHA HIT, three items to assess changes in headache impact since Time 1, and the SF-8 Health Survey. The sequence of administration of the items remained the same from Time 1 to Time 2, with the HIT-6 items always administered first so as to minimize any response effects on the test– retest reliability study.

Calibration and scoring HIT-6 First, we estimated an IRT scale (IRT-Total HIT) based on all available item responses, including the DynHA HIT (total of 34 headache impact items). The IRT-Total HIT scale was scored to have a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 in the general population of recent headache sufferers. [3] Next we examined which of two choices of item category weights to assign to HIT-6 item responses that could be summed to closely approximate the IRT-Total HIT score. In method 1 the following item category weights were assigned to each HIT-6 item response: never = 6, rarely = 8, sometimes = 10, very often = 12, and always = 14. In method 2 the following item category weights were assigned to each HIT-6 item response: never = 6, rarely = 8, sometimes = 10, very often = 11, and always = 13. We examined the concordance between the IRT-Total HIT scale scores and HIT-6 scale scores by correlational methods, by plots, and by calculating the score difference between the two scales to determine the choice of item category weights to use in scoring HIT-6.

Reliability analyses Reliability was assessed using internal consistency, alternate-forms, and test–retest methods. For internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s a was estimated for HIT-6 items at Time 1 and Time 2. Alternate forms reliability was estimated by computing the intra-class correlation coefficient between HIT-6, DynHA HIT, and IRT-Total HIT scale scores at Time 1 and between HIT-6 and DynHA HIT scale scores at Time 2. Test–retest reliability was assessed by computing the intraclass correlation between HIT-6 scale scores at Time 1 and Time 2. The test–retest reliability analyses were carried out first using all individuals who completed Time 1 and Time 2 questionnaires and second only using a subset of individuals who had reported no change in headache impact during that interval.

To evaluate the precision of HIT-6 scores at the level of the individual patient, measurement error was estimated for various HIT-6 score levels using IRT methods (EAP score estimation) [10] and the item parameters established for HIT-6 items. [4]

Construct validity Construct validity was evaluated in terms of HIT-6 correlations with generic health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures that included the SF-8 scales and physical and mental health summary measures. We hypothesized that HIT-6 would correlate negatively with general health status (the greater the headache impact the lower the general health status). We also expected that HIT-6 would correlate stronger with the physical measures than with the mental measures of general health status.

Construct validity was also evaluated in clinical tests of discriminant validity using the method of known groups validity. [11] The method of known groups validity compares mean scale scores across groups know to differ on a clinical criterion measure. In this study, two clinical criterion measures were used. The first was self-ratings of headache pain severity. Participants were asked to rate the severity of their headache pain on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as it can be). Participants were categorized as mild if they answered 1, 2, or 3, moderate if they answered 4, 5, 6, or 7, and severe if they answered 8, 9, or 10. The second clinical criterion was the probability of migraine diagnosis, which was based on questions concerning the frequency of six migraine symptoms used in previously conducted epidemiology studies of migraine. [12] A series of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to test performance of HIT-6 relative to the IRT-Total HIT scale in distinguishing between participants that differed in headache severity and probability of migraine diagnosis. RV coefficients were computed by dividing the F-statistics of each scale by the largest F-statistics observed among all scales in each test. [13, 14] We expected to observe higher scores (greater headache impact) on both HIT scales among patients with more severe headache and among patients with a higher probability of a migraine diagnosis. However, RV coefficients were expected to be higher for the IRT-Total HIT scale in comparison to HIT-6.

Screening The accuracy of HIT-6 in patient level screening was investigated at the recommended DynHAHIT cut-point score (>56) for a migraine diagnosis. [15] The agreement in classification at the recommended cut-point score was compared across HIT-6 and the IRT-Total HIT scale.

Responsiveness of HIT-6 The responsiveness of HIT-6 scores was evaluated by comparing average score changes across groups of study participants differing in self-reported change in headache impact. For these analyses, we used data from the 1998 NSHI [3] that included the developmental version of HIT-6. Three self-reported change measures were in the follow-up survey (Appendix A). Respondents were classified into three groups, ‘better’, ‘same’, or ‘worse’ depending upon their responses to the three questions. Changes in HIT-6 and IRT-Total HIT scale scores were calculated by subtracting baseline scores from follow-up scores. The method of known groups validity and ANOVA methods were used to compare changes in HIT-6 and IRT-Total HIT scale scores across groups differing in selfreported change. RV statistics were calculated to compare the performance of HIT-6 relative to the IRT-Total HIT scale in distinguishing between groups.

Reading level The reading level of the HIT-6 was evaluated using the Flesch–Kincaid Reading Ease and Grade Level index. This Flesch–Kincaid evaluates readability based on the average number of syllables per word and the average number of words per sentence. The Reading Ease procedure assigns a score between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating more difficult material. The Flesch– Kincaid Grade Level index indicates a school grade reading level. For example a score of 8.0 means that an eighth grader would understand the questions. [16]

Results

Sample

At Time 1 1,103 eligible respondents completed the survey. The majority of participants were female (73%) and the average age of the sample was 37 years. Approximately 14 days (on average) after completion of the Time 1 survey, 540 participants completed the survey at Time 2. The majority of the participants at Time 2 were female (72%) and the average age of the sample was 37.5 years. Despite 50% attrition, the samples were relatively the same in age and gender across the two time points, suggesting that the subset of the baseline sample completing the follow-up questionnaire was representative.

Calibration and scoring HIT-6

Table 1

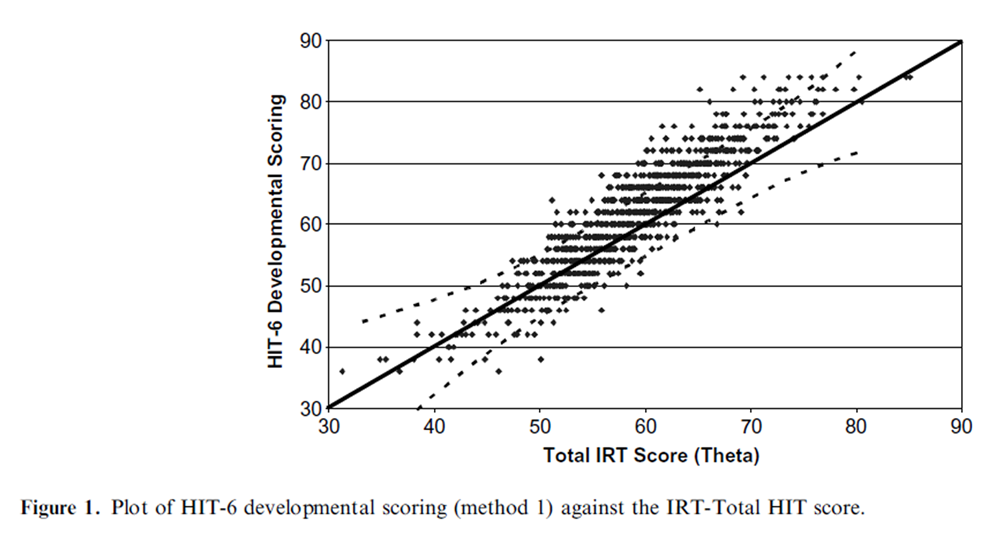

Figure 1

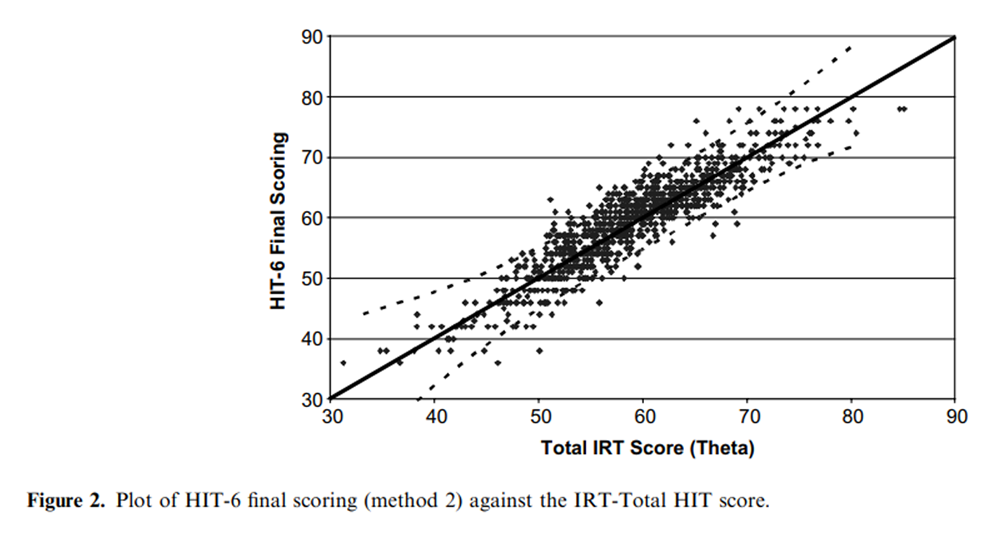

Figure 2

Table 2

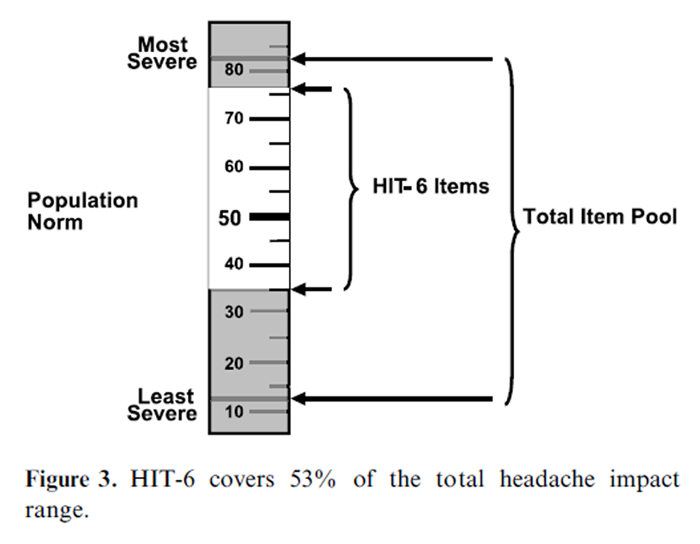

Figure 3

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

Table 6 As shown in Table 1, the correlation between the two methods of computing a sum score for HIT-6 was high (0.993) as were the correlations between each of the HIT-6 sum scores and the IRT-Total HIT scale score (method 1: r = 0.906; method 2: 0.903). Figures 1 and 2 show that HIT-6 scoring method 2 (Figure 2) had a closer match with the IRT-Total HIT scale score. Method 1 overestimated headache impact at the high impact range (Figure 1) compared to method 2. Also, in evaluating the correspondence between HIT-6 scale scores and the IRT-Total HIT scale there were more data points outside the 95% confidence interval drawn around the identity line for the HIT-6 scale scored under method 1 (Figure 1) compared to method 2 (Figure 2). Lastly, the mean difference between HIT-6 scored with method 1 and the IRTbased score was 2.76 (range )11.26 to 17.93) while the mean difference between HIT-6 scored with method 2 and the IRT-based score was 0.59 (range)11.26 to 11.92) (Table 2). In light of these results, the focus of the remaining results for HIT-6 was based on scoring method 2.

Figure 3 illustrate the range of headache impact covered by HIT-6 item parameters in relation to the range of headache impact measured by the total HIT item pool. As shown, the item parameters estimated for HIT-6 items covered 53% of the range of headache impact measured by the total HIT item pool.

Reliability analyses

Results of reliability analyses are presented in Table 3. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s a) reliability of HIT-6 scale scores was 0.89 at Time 1 and 0.90 at Time 2. The intra-class correlation between HIT-6 and the total HIT score (alternate forms reliability) was 0.90 and between HIT-6 and HIT-DynHA (alternate forms reliability) was 0.84. The intra-class correlation between HIT-6 scores at Time 1 and Time 2 (test–retest reliability) for the total sample (n = 540) was 0.78. The intra-class correlation between HIT-6 scores at Time 1 and Time 2 (test–retest reliability) for the ‘stable’ sample (n = 245) was 0.80.

Table 4 presents the 95% confidence intervals around HIT-6 and IRT-based scale scores across eight levels of the IRT-based scale. As shown, for scores between 45 and 69 (91% of those studied), where HIT-6 was most precise, 95% confidence intervals of approximately five points were observed for individual patient scores. In comparison, 95% confidence intervals of approximately three points were observed for individual patient scores between 45 and 70 on the IRT-Total HIT score.

Construct validity

Correlations between HIT scales (HIT-6 and IRTTotal HIT scale) and SF-8 scales and summary measures are presented in Table 5. As expected, all correlations with SF-8 scales and summary measures were negative. Correlations between the IRTTotal HIT scale and SF-8 scales and summaries were stronger than those observed between HIT-6 and SF-8 scales and summaries. The pattern of correlations between both HIT scales (HIT-6 and total HIT) and SF-8 scales and summaries was nearly identical, with the highest correlations observed between HIT scales and the SF-8 role physical (RP) and social functioning (SF) scales and the lowest correlations observed between HIT scales and the SF-8 bodily pain (BP) and mental health (MH) scales. In relation to the SF-8 physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) summary measures, both HIT scales correlated higher with PCS than MCS.

Table 6 presents results from tests of the validity of HIT-6 and the IRT-Total HIT scale in discriminating among groups known to differ in headache severity and the probability of a migraine diagnosis. In the test involving headache pain severity as the criterion measure, both scales show large and statistically significant differences in mean scores across the headache pain severity groups, with the more severe pain groups scoring greater headache impact. For each headache pain severity group, the mean scores on both scales were within one-half a point of each other. Significance tests showed both scales to perform equally well at discriminating across the headache pain severity groups. In tests involving the probability of a migraine diagnosis as the criterion measure, both scales showed large and statistically significant differences in mean scores across the diagnostic groups, with the migraine group scoring greater headache impact than the non-migraine group. The mean HIT-6 and total HIT scores were within one-half a point of each other for the nonmigraine group and the migraine group. Significance testing shows that HIT-6 was 18% less efficient than the IRT-Total HIT scale in discriminating between migraine and non-migraine groups, as determined by the F and RV statistics.

Screening

Table 7

Table 8 Results of tests of the accuracy of HIT-6 relative to the cut-point score of >56 on the IRT-Total HIT scale used in patient-level screening for the probability of a migraine diagnosis are presented in Table 7. The HIT-6 correctly classified 88.8% of the sample at the recommended cut-point score for the IRT-Total HIT scale, with sensitivity and specificity statistics of 93.1 and 79.4%, respectively.

Responsiveness

Table 8 presents the results of analyses that compare the relative performance of HIT-6 and IRT Total HIT scale scores in responding to self-reported change. As shown, both scales showed large and statistically significant differences in mean change scores across the self-reported change groups. Scale scores improved on average among those respondents who self-reported improved headache impact, while scores declined on average among those respondents who self-reported worsening headache impact. Average score changes were generally less than one-point among those respondents who self-reported no change in headache impact. Significance tests showed that the HIT-6 scale performed equally well or better at discriminating across the self-reported change groups.

Reading level

Results of the Flesch–Kincaid readability test found the HIT-6 to have a Flesch–Kincaid Reading Ease score of 66.2 and a Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level Index of 7.4.

Discussion

The IRT model estimated for a ‘pool’ of items from widely used measures of headache impact was very useful in constructing an efficient ‘static’ short form survey of headache impact for use in screening and monitoring patient outcomes. The items in HIT-6 cover the content areas found in widely used measures of headache impact, including pain, social-role limitations, cognitive functioning, psychological distress, and vitality. Although the HIT-6 is shorter than most widely used measures of headache impact, it demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity for use in group-level studies throughout the entire range of headache impact studied. HIT-6 was almost as accurate as the IRT-Total HIT scale in identifying persons above the established cut-point score for probable diagnosis. Using IRT-based scoring methods, the HIT-6 was shown to be precise enough to detect differences on average of approximately five points in headache impact at the level of the individual for all but the most extreme score levels.

Based on the IRT item parameters estimated for HIT-6 items, HIT-6 was shown to cover 53% of the range of headache impact measured by entire HIT item pool (54 items), which spans from 1.5 standard deviations below (mild impact) to 2.5 standard deviations above (severe impact) the norm score of 50 observed among recent headache sufferers. In this range, 91% of the total general population of recent headache sufferers scored on the scale defined by the total HIT item pool. In comparison to the total HIT item pool, HIT-6 showed the biggest gap in measurement at the mild headache impact range. The total HIT item pool measures down to nearly 4 standard deviations below the normative score of 50, while HIT-6 measures only 1.5 standard deviations below the normative score, a gap of 2.5 standard deviation units. The implication is that HIT-6 is may be prone to ceiling problems in measuring patients with very mild headache impact. However, this may not be too problematic since less than 10% of recent headache sufferers in the general population scored more than 1.5 standard deviations below (mild impact) the normative score on the scale defined by the total HIT item pool. Furthermore, despite the relatively limited range of headache impact covered by HIT-6 compared to the range defined by the entire HIT item pool, this short form is more inclusive than other instruments currently being used to asses headache impact. [3]

Using classical psychometric methods to assess reliability HIT-6 was shown to exceed the minimum standard (>0.70) for group level comparisons. Internal consistency reliability estimates approached levels recommended for comparisons of individual patients (>0.90) despite the heterogeneity of item content. test–retest reliability estimates suggest that HIT-6 scores are stable over time among respondents showing no change in headache impact. Under the IRT framework, where reliability and measurement error varies across the score distribution, HIT-6 was extremely reliable across a fairly wide range of headache impact scores. HIT-6 was most precise between scores of 45 and 70, where the 95% confidence interval around an individual patient score was approximately five points on average (corresponding to reliability greater than 0.90).

Correlations between HIT-6 scale scores and measures of HRQOL were negative. As expected, respondents with higher scores on HIT-6 indicating greater headache impact had lower HRQOL scores. This is consistent with many studies showing diminished HRQOL attributed to headache and migraine. [17–20] The relationship between HIT-6 and HRQOL scales was at best moderate, with correlations all below 0.40, which may be a function of the heterogeneity of content of HIT-6 items. The pattern of correlations suggested that HIT-6 was more related to measures of physical health, particularly in the role functioning domains, than MH. This pattern was true for both HIT-6 and IRT-Total HIT scores. However, across al HRQOL scales, the IRT-Total HIT score showed substantially larger correlations with HRQOL than those observed between HIT-6 and HRQOL. This difference may in part be explained by the differences in reliability and the range of impact measured by the two HIT scales.

Results of discriminant validity testing showed that HIT-6 reached the same statistical conclusions about group differences, as did the HIT scale based on the total item pool. In the test involving migraine diagnosis, the RV coefficient for HIT-6 was nearly 20% below that observed for the HIT scale based on the total item pool. In the test involving headache severity, HIT-6 performed as well as the HIT scale based on the total item pool. In both tests, HIT-6 scores showed more variability among the groups expected to have mild headache impact (no migraine and mild severity groups). This is consistent with the fact that HIT-6 is less precise in measuring mild headache impact and therefore can be expected to have greater measurement error than the HIT scale based on the total item pool. Consequently, HIT-6 showed more variability in scores for groups with mild headache impact, which likely contributed to the superior performance of the HIT scale based on the total item pool in the test involving migraine.

Another important finding from the discriminant validity tests was the observations that mean scores on HIT-6 were within one-half a point of mean scores based on the total item pool for each of the criterion groups (diagnosis and severity). The implication of these findings is that they lend support to the interchangeability of scores based on HIT-6 and HIT scores based on the total item pool, at least in group level comparisons. Because of the high degree of correspondence in scores, norms and interpretation guidelines established for HIT will be useful for interpreting scores on HIT- 6. However, more studies are needed to better understand the interchangeability of scores at the level of individual patients, particularly at the mild headache impact range where HIT-6 is less precise.

Many barriers exist that contribute to the lack of detection and appropriate care of migraine headaches [21] , one of which concerns the length of time patients have to consult with their doctor. Studies of consultation in general practice [21, 22], where migraine patients most often consult initially [23], suggest that the length of time of consultation, which typically ranges from 5 to 8 min, is insufficient for patients to adequately describe their symptoms and the degree of resulting disability associated with their headaches. Furthermore, there are no objective markers or diagnostic tests that define migraine. One of the potential uses of HIT-6 in clinical practice may be as a first stage screen for the diagnosis of migraine headache. In this study, HIT-6 was found to correctly classify nearly 90% of those respondents who scored higher than the cut-point score (>56) for a probable migraine diagnosis on the IRTTotal HIT scale. More importantly, HIT-6 can be administered and scored in 2–3 min time, which is well within the typical range of consultation time in general practice. However, clinic based studies to examine the positive predictive value of HIT-6 are warranted.

The evidence from this study showed that HIT-6 was responsive to self-reported change in headache impact. Across all three criterion measures of change, HIT-6 was equal to or better than the HIT scale based on the total item pool in discriminating between groups of patients differing in self-reported changes in headache impact. Of importance was the finding that average changes in scores for each criterion group were very similar for both HIT scales, which lends further support to the point raised above about the interchangeability of HIT-6 and HIT scores. In this study, HIT-6 scale scores declined (decreased headache impact) by approximately three points on average among persons self-reporting improvement on all three criterion measures of change. A decline of this magnitude is roughly 3/10ths of a standard deviation, which in terms of effect size is considered small. While further study is necessary to better understand the responsiveness of HIT-6 in clinical studies, the results of this study offer preliminary estimates of change in HIT-6 scale scores that could be considered meaningful from the patient’s perspective.

The evidence presented from this study suggested that we successfully achieved our goals of developing a brief measure of headache impact that is(1) psychometrically sound; and

(2) clinically relevant.Our efforts resulted in a six-item questionnaire that proved to be reliable and valid for group-level comparisons, patient-level screening, and responsive to changes in headache impact. The HIT-6 items were shown to cover a substantial range of headache impact as defined by a much larger pool of items and include content areas found in most widely used tools for measuring headache impact. Modifications made to HIT-6 items resulted in an instrument that was more easily translated into other languages. Translations of HIT-6 are now available in 27 languages in total through QualityMetric and studies are currently being conducted to evaluate the performance of the translated forms in clinical studies.

References:

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society.

Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache

disorders, cranial neuralgias, and facial pain.

Cephalalgia 1992; 12: 229–237.Solomon GD, Price KL.

Burden of migraine: A review of its socioeconomic impact.

Pharmacoeconomics 1997; 11(Suppl 2): 1–10.Ware JE, Bjorner JB, Kosinski M.

Practical implications of item response theory and computerized adaptive testing:

A brief summary of ongoing studies of widely used headache impact scales.

Med Care 2000; 38(Suppl II, 9): 1173–1182.Bjorner JB, Kosinski M, Ware JE Jr.

Calibration of an item pool for assessing the burden of headaches:

An application of item response theory to the Headache Impact Test (HIT™).

Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 913–933.Bullinger M, Alonso J, Apolone G, et al.

Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality:

The International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project.

J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51(11): 913–923.Gandek B, Alacoque J, Uzun V, Andrew-Hobbs M.

Translating the Short-Form Headache Impact Test (HIT-6)

in 27 countries: Methodological and conceptual issues.

Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 975–979.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B.

SF-8 Health Survey Manual – How to Score and Interpret

Single-Item Health Measures: A Manual

for Users of the SF-8 Health Survey.

Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated, 2001.Stewart WF, Lipton R, Liberman J.

Variation in migraine prevalence by race.

Neurology 1996; 47: 52–59.Stewart WF, Lipton R, Kolonder K, Liberman J, Sawer J.

Reliability of the migraine disability assessment score

in a population-based sample of headache sufferers.

Cephalgia 1999; 19: 107–114.Bock RD, Mislevy RJ.

Adaptive EAP estimation of ability in a microcomputer environment.

Appl Psychol Meas 1982; 6: 431–444.Kerlinger FN.

Foundations of Behavioral Research.

New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1973.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Celentano DD, Reed ML.

Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States:

Relation to age, income, race and other

sociodemographic factors.

J Am Med Assoc 1992; 267(1): 64–69.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE.

The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). II.

Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in

measuring physical and mental health constructs.

Med Care 1993; 31: 247–263.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek AE.

Comparison of methods for scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36

health profiles and summary measures: Summary of

results from the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS).

Med Care 1995; 33(Suppl 4): AS264–AS279.Bjorner JB, Ware JE, Kosinski M, Diamond M, Tepper S.

Validation of the Headache Impact Test using

patient-reported symptoms and headache severity.

In: Olesen J, Steiner TJ, Lipton RB (eds),

Reducing the Burden of Headache.

Oxford University Press, 2003.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS.

Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index,

Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel.

Memphis, TN: Naval Air Station, 1975.Lipton RB, Hamelsky SW, Kolodner KB, Steiner TJ, Stewart WF.

Migraine, quality of life, and depression:

A population-based case–control study.

Neurology 2000; 55(5): 629–635.Meletiche DM, Lofland JH, Young WB.

Quality-of-life differences between patients with

episodic and transformed migraine.

Headache 2001; 41(6): 573–578.Monson MJ, Lainez MJ.

Quality of life in migraine and chronic daily headache patients.

Cephalalgia 1998; 18(9): 638–643.Osterhaus JT, Townsend RJ, Gandek B, et al.

Measuring the functional status and well-being of

patients with migraine headaches.

Headache 1994; 34: 337–343.Edmeads J, Lainez JM, Brandes JL, Schoenen J, Freitag F.

Potential of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire

as a public health initiative and in clinical practice.

Neurology 2001; 56: S29–S34.Carr-Hill R, Jenkins-Clarke S, Dixon P, et al.

Do minutes count? Consultation lengths in general practice.

J Health Ser Res Policy 1998; 3: 207–213.Hu XH, Markson LE, Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Berger ML.

Burden of migraine in the United States:

Disability and economic costs.

Arch Intern Med 1999; 159(8): 813–818./

Return to HEADACHE

Since 2-12-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |