Do Manual Therapy Techniques Have a Positive Effect

on Quality of Life in People With Tension-type Headache?

A Randomized Controlled TrialThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016 (Aug); 52 (4): 447—456 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Gemma V. Espí-López , Cleofas Rodríguez-Blanco, Angel Oliva-Pascual-Vaca,

Francisco J. Molina-Martínez, Deborah Falla

Department of Physiotherapy,

University of Valencia,

Valencia, Spain

deborah.falla@bccn.uni-goettingen.deBACKGROUND: Controversy exists regarding the effectiveness of manual therapy for the relief of tension-type headache (TTH). However most studies have addressed the impact of therapy on the frequency and intensity of pain. No studies have evaluated the potentially significant effect on the patient's quality of life.

AIM: To assess the quality of life of patients suffering from TTH treated for 4 weeks with different manual therapy techniques.

DESIGN: Factorial, randomized, single-blinded, controlled clinical trial.

SETTING: Specialized center for the treatment of headache.

POPULATION: Seventy-six (62 women) patients aged between 18 and 65 years (age: 39.9 ± 10.9) with either episodic or chronic TTH.

METHODS: Patients were divided into four groups: suboccipital inhibitory pressure; suboccipital spinal manipulation; a combination of the two treatments; control. Quality of life was assessed using the SF-12 questionnaire (considering both the overall score and the different dimensions) at the beginning and end of treatment, and after a one month follow-up.

RESULTS: Compared to baseline, the suboccipital inhibition treatment group showed a significant improvement in their overall quality of life at the one month follow-up and also showed specific improvement in the dimensions related to moderate physical activities, and in their emotional role. All the treatment groups, but not the control group, showed improvements in their physical role, bodily pain, and social functioning at the one month follow-up. Post treatment and at the one month follow-up, the combined treatment group (suboccipital inhibitory pressure and suboccipital spinal manipulation) showed improved vitality and the two treatment groups that involved manipulation showed improved mental health.

CONCLUSIONS: All three treatments were effective at changing different dimensions of quality of life, but the combined treatment showed the most change. The results support the effectiveness of treatments applied to the suboccipital region for patients with TTH.

CLINICAL REHABILITATION IMPACT: Manual therapy techniques applied to the suboccipital region, for as little as four weeks, offered a positive improvement in some aspects of quality of life of patient's suffering with TTH.

Key words: Treatment outcome - Tension-type headache - Musculoskeletal manipulations - Quality of life.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Tension-type headache (TTH) is the most common primary headache. The high prevalence of TTH is associated with significant social and economic impact, and is responsible for a high percentage of visits to different health professionals. [1, 2] Understandably, TTH also affects quality of life, including performance of work and everyday household activities, social life, and leisure activities. [3]

Stress and pericranial muscle spasms might play an important role in the pathophysiology of this disorder. [4] These factors, as well as mechanisms involving central and peripheral sensitization, explain the presence of painful pericranial tenderness and the lower pain threshold observed in this region in patients with TTH. Tender points on the neck and head also become more sensitive. [5]

Controversy exists regarding the effectiveness of physical therapy for the relief of TTH. [6] The evidence that spinal manipulation alleviates TTH is encouraging, but not always conclusive due to the low quality of the studies. [7] There is the need for further randomized controlled trials of high quality to specifically evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions in patients with TTH. [8] Moreover, most studies have addressed the impact of therapy on the frequency and intensity of headache, and occasionally the impact of such pain or its duration, but no studies have evaluated the potentially significant effect on the patient’s quality of life. In this study we hypothesized that manual therapy techniques applied to the suboccipital region with the aim of reducing soft tissue tension, both separately and in combination, would improve aspects of quality of life of patients suffering with TTH. Thus, this study assessed the effectiveness of manual therapy on the overall quality of life and different dimensions of quality of life in patients with episodic (ETTH) or chronic (CTTH) TTH. Specifically, we evaluated the effect of suboccipital inhibitory pressure (SI) and suboccipital manipulation (SM) and the combination of both. Changes in quality of life were noted immediately after four weeks of intervention and at a one-month follow-up

Materials and methods

Patients

Table I

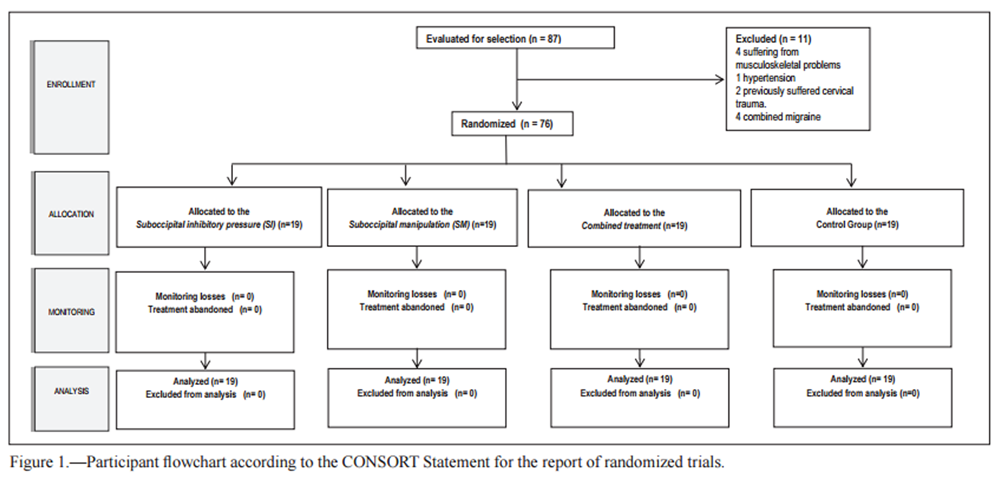

Figure 1 Patients were considered for the study if they were clinically stable and without any other concomitant disease. Subjects were enrolled for the study if they were aged between 18 and 65 years, had been diagnosed with TTH for more than three months, had episodes of headache lasting from 30 minutes to 7 days, and fulfilled two or more of the following characteristics: bilateral location of pain, non-pulsatile pressure pain, mild to moderate pain, a headache that does not worsen with physical activity. In addition, the headache could be associated with pericranial tenderness and should be controlled pharmacologically but the medication could not be altered during the course of the study. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table I. During the three month period prior to starting the study, an experienced neurologist was responsible for identifying patients and confirming the diagnosis of TTH. A radiological examination was performed on all participants (as part of the routine evaluation in this setting) to rule out major structural abnormalities in this regard and pathological rigidity. Eighty-seven subjects were initially selected for the study and 76 were included due to the exclusion of 11 subjects (Figure 1). Of those included, 62 were women (81.6%) and 14 were men (18.4%). The mean age was 39.9 years (SD 10.9), ranging from 18 to 65 years. The study was conducted from March to December, 2013 at the University of Valencia (Spain) and treatment was carried out in a specialized center for the treatment of headache. The sample consisted of patients with TTH diagnosed by an experienced neurologist considering headache characteristics established by the International Headache Society (IHS). [9, 10]

Study design

The study was a factorial, randomized, single-blinded, controlled clinical trial. After the initial clinical interview conducted by a specialist manual therapist, patients were randomly assigned to four groups:1) SI treatment;

2) SM treatment;

3) combination of SI and SM; and

4) control group using a computer-generated random sequence (randomized.com); which was carried out by an assistant who was unaware of the treatments administered to each group or the study objectives.The sampling processes were performed according to nonprobabilistic convenience sampling techniques. Patients and the examiner were unaware of critical study factors. The therapists were not informed of the type of study being conducted or the aim of the study, and statistical analyses were conducted by an external specialist.

The number of subjects required in each group was estimated with the nQuery Advisor software program. For an ANOVA with one inter-subject factor, with four groups, and assuming a 5% significance level for a large effect, the required number was 19 subjects per group.

All patients were assessed under the same conditions prior to treatment, after treatment (at 4 weeks), and at a follow-up (one month after completion of treatment). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia (Spain) with the number H1380701837435 and prior to their assignment to a group, the subjects gave written informed consent. The trial was registered at Trial.gov with register number NCT02455323.

Interventions

Each subject received four treatment sessions, each lasting approximately 20 minutes, with 7-day intervals. Treatments were performed at a specialized center for the treatment of headache. Prior to the intervention and with the patient in a supine position, a test for a possibly compromised vertebral artery was performed bilaterally to determine the advisability of treatment. This test was applied to all subjects, including the control subjects. The specific etiology of signs and symptoms caused by the test as well as its effectiveness for ensuring the absence of vascular injury remain unclear. [11, 12] However, before enrolment in the study, patients with symptoms suggestive of possible vertebrobasilar insufficiency were excluded. Subsequently, with the subject in the same position on a treatment bed, the treatment technique was applied according to the group allocation. The therapists had more than 10 years’ experience each in the application of manual therapy for patients with primary headaches. Techniques were always applied cautiously by the experienced specialists in manual therapy to avoid any potential adverse events. Adverse events were monitored by the therapists throughout the treatment sessions and patients were specifically asked at the beginning of subsequent treatment sessions about the occurrence of any adverse events since the last treatment session.SI. — The suboccipital musculature was palpated until contact was made with the posterior arch of the atlas, and progressive and deep gliding pressure was applied, pushing the atlas anteriorly. The occiput rested on the hands of the therapist while the atlas was supported by the fingertips. Finger pressure was maintained for 10 minutes to produce the proposed therapeutic effect of inhibiting the suboccipital soft tissues. The aim of the technique is to suppress spasm of the muscles and in general of the suboccipital soft tissues which may be contributing to dysfunctional mobility of the occiput, atlas, or even the axis. [13]

SM. — This technique was performed along an imaginary vertical line passing through the odontoid process of the axis. No flexion or extension and very little lateral flexion were used. Application was bilateral. First, cephalic decompression was performed lightly, followed by small circumductions. Selective tension was applied to take up tissue slack and create a firm joint barrier. Manipulation was then performed with rotation towards the manipulated side in a helicoidal cranial movement. This technique was applied with the aim of increasing occiput, atlas, and axis joint mobility. [14-16]

Combined treatment. — This group received the above two techniques always in the same sequence: first the SI technique followed by the SM.

Control group. — The subjects received no treatment, but attended the same number of sessions, maintaining the resting position for longer than the treatment groups, and underwent the same evaluations (test for arterial compromise, and the three assessments).

Resting position. — The subjects remained in a resting position in supine with a neutral position of their head and neck for 5 minutes after treatment in the treatment groups, and for 10 minutes in the control group.

Evaluation

A clinical interview was conducted by a specialist Manual Therapist in the month preceding the study to gather headache-related data from the subjects. These included major aspects for TTH verification, including frequency of noted pain (less than 15 days monthly = ETTH; more than 15 days monthly = CTTH), location and laterality of pain, type of pressure and intensity response to the classification of the IHS, [9, 10] and severity of pain.

The SF-12v2 (Short Form 12 Health Survey) health status questionnaire was used to assess the subject’s quality of life and the questionnaire has established reliability. [17, 18] The Spanish version presented by Alonso et al. [19] and Monteagudo et al. [20] was adopted. The SF- 12v2 is a reduced version of SF-36 [17] and is designed to reduce the length of the questionnaire by including fewer questions. The initial version of the questionnaire was developed in the USA in 1994, [21] and the version used in the present study is from 2002. [22] The survey provides a health status profile consisting of 12 questions taken from the 8 dimensions of SF-36: [23] Moderate activities (Physical Functioning), Climb several flights of stairs (Physical functioning), Accomplished less than you would like (Physical Role), Limited in kind of work (Physical Role), Extent Pain interfered (Bodily Pain), Health in general (General Health), Energy (Vitality), Social time (Social Functioning), Accomplished less than you would like (Emotional Role), Didn’t do work as carefully as usual (Emotional Role), Calm and Peaceful (Mental Health), Downhearted and depressed (Mental Health). Higher scores indicate better health, up to a maximum of 100 points. This is a registered instrument and its use was authorized for the present study.

The quality of life was assessed using this instrument at three stages of the study: before treatment, after treatment (at 4 weeks), and at follow-up (one month after completion of treatment). All subjects were evaluated under the same conditions for the three study phases.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by an independent external statistician blinded to group allocation. Descriptive statistical analyses were made for the overall sample, and then for the groups separately, considering the absolute and relative frequencies, correlations between the study variables, and the mean scores with their standard deviations and confidence intervals.

For the pre-test, an ANOVA was used which confirmed the homogeneity of the groups before starting treatment, including the calculation and interpretation of the effect size (0.2 was regarded as small, 0.5 as medium and 0.8 as large) and the Levene statistic to verify the assumption of homoscedasticity. In cases of statistical significance, the Welch and the Brown-Forsythe robust F-tests were applied. The t-test for related samples was used to compare the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up means (for each group separately), followed by the calculation and interpretation of the effect size. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test was applied separately for each group and for each measure to verify compliance with normality. When the data were not normally distributed, differences were evaluated by the non-parametric Wilcoxon Test. The level of significance set for all analyses was 5%.

Results

Demographic analysis and headache characteristics

Table II

Table III

Table IV A

Table IV B

Table IV C Of the sample, 40.8% of the subjects suffered from CTTH, and 59.2% from ETTH. Table II presents the headache characteristics of the study sample. The mean value of pain intensity as evaluated by the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was 6.5 (SD 1.7). In 51.3% of the patients, pain was triggered by physical or mental tiredness. Stress was considered to be the most conditioning factor for 69.7% of the patients. On the other hand, among stress factors, work-related factors affected 52.6% of the sample, while emotional, family and studying-related factors affected 19.7%, 19% and 7.9% respectively of the entire sample.

Analysis of quality of life

At the start of treatment, the subjects presented lower than normative values for their quality of life (mean 39.2, SD 3.9). The overall quality of life remained unchanged in all groups, except in the SI group at the follow-up with a medium effect size (Table III). The individual analyses by dimension revealed that “Moderate activities” in the Physical Functioning dimension represented no major change in the SI group. Regarding the Physical Role, the dimension “Accomplished less than you would like” showed a statistically significant change in all groups, while “Limited in kind of work” only improved in the three treatment groups but not the control group.For Bodily Pain and Social Functioning, improvements were noted in all treatment groups but not the control group. With regard to Vitality, both of the comparative evaluations in the combined treatment group showed significant improvements with the effect size being medium-to-high. For the Emotional Role, “Accomplished less than you would like”, a significant change was observed for the SI group and the combined treatment group, and “Didn’t do work as carefully as usual” improved in the SM and combined treatment group. Finally, for Mental Health, “Calm and Peaceful” showed significant improvement after treatment in the SM group, and at the one month follow-up in the SM and combined treatment group, while “Downhearted and depressed “ improved in the combined treatment group at both evaluations (Table IV).

No adverse events were reported.

Discussion

As expected, the results confirm that TTH has specific noted pain characteristics, [10, 11] and that TTH significantly reduces quality of life. [1, 24] Considering their overall general health, the patients presented with relatively poor health before treatment, and all groups improved slightly after treatment, but without major changes. In view of these results we evaluated different variables of the general health questionnaire separately to specifically understand the areas in which the treatment was effective.

Regarding Physical Functioning, the limitations for “Moderate activities” showed positive improvement in the SI treatment group at the one month follow-up. Since physical effort is one of the most important triggers of TTH, this finding suggests that SI was the most effective treatment for improving this aspect of quality of life. Nevertheless, it had no effect on “Climb several flights of stairs”; thus no treatment appears to be beneficial for this aspect of physical function. Reduced work productivity (“Accomplished less than you would like”) due to emotional problems in the Emotional Role dimension showed positive changes in the two treatment groups that included SI treatment. In contrast, the reduced level of care or attention paid to everyday activities because of emotional problems (“Didn’t do work as carefully as usual”) improved in the two groups that received SM. The combined treatment also had a significant effect on the vitality dimension (“Energy”, or the frequency of feeling full of energy). With regard to Mental Health, the frequency of feeling calm and quiet (“Peaceful”) also showed positive changes for the two treatments groups which including the manipulation, and the frequency of feelings of discouragement and depression (“Downhearted and depressed”) improved significantly for the group that received the combined treatment.

In the Physical Role, the reduced ability to perform everyday activities (“Accomplished less than you would like”) improved in all groups, including the control group (although for the latter the effect size was smaller). However, the limitation in the kind of work that could be undertaken (“Limited in kind of work”), as well as the Bodily Pain and Social Functioning dimensions, improved in all of the treatment groups, but not in the control group, suggesting that the three treatments applied to the suboccipital soft tissues were effective in these aspects related to the quality of life.

The importance of the present study in understanding and treating TTH is that, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, it is the first to evaluate the separate dimensions of quality of life in people with TTH. Other studies have applied exercise programs combined with manual therapy showing a significant reduction in the frequency, intensity, and duration of pain, and in the subject’s overall mental health. For instance, Van Ettekoven and Lucas [25] evaluated the effect of a six week program of craniocervical exercises combined with massage and mobilization in people with TTH and demonstrated significant effects on headache frequency, intensity, duration of pain, and quality of life with clinically relevant effect sizes. Moreover, a number of studies have shown that treatment with cervical manipulation is effective in reducing the frequency of pain, and the duration and intensity of headaches. [26, 27] Moreover, the combination of different techniques together with manual therapy can significantly reduce levels of pain intensity. [28, 29] However, since the various techniques were applied in combination, it is not possible to distinguish which was the most effective.

One of the techniques applied in the present study was the inhibition of suboccipital tissue, selected with the aim of reducing tension in the suboccipital musculature, which is often responsible for initiating a headache. Only one previous study has evaluated the efficacy of the suboccipital inhibition technique, [15] but it was applied in combination with muscle-energy techniques to the suboccipital muscles, and it did not assess the patients’ quality of life. [30, 31] Castien et al. in 2011 [32] showed the effectiveness of a combined treatment of mobilization of the cervical and thoracic spine and postural correction exercises, but again, quality of life was not assessed and the application of individual techniques was not evaluated. The specific treatments applied in the current study have recently been evaluated in combination and individually, [15, 16, 33] however such studies did not analyze the quality of life in its various dimensions.

Overall, the present results indicate that the application of the three different treatments were effective at improving various aspects of quality of life in people with TTH, with differences noted between the treatments approaches. However, a longer follow-up period would be required to determine how long the effects last, as well as to assess other headache related features. [34] Moreover, we applied a relatively short intervention even though current guidelines suggest longer interventions for TTH. However, even though the treatment volume was low (4 treatments every 7 days), the interventions had significant effects. Other studies evaluating the effects of vertebral mobilization, spinal manipulation or suboccipital inhibition treatment have also reported positive effects after interventions with a similar number of sessions [13, 15, 16] or even less. [35] We assume that the participants remained blinded to their group allocation throughout the entire trial but we did confirm this e.g. using a de-blinding questionnaire after each treatment session. However, other work has demonstrated that it is possible to conduct a single-blinded manual therapy RCT with placebo and to maintain the blinding throughout multiple treatment sessions over several months. [36]

It should be noted that the treatment techniques were performed by qualified therapists with extensive experience. Moreover, the study adhered to the guidelines presented by Rushton et al. [37] for examination of the cervical region for potential cervical arterial dysfunction prior to orthopaedic manual therapy interventions. This included a detailed patient history and physical examination. Thus it must be emphasized that the application of spinal manipulative techniques requires specialized training. Moreover, it cannot be excluded that mobilization, rather than manipulation, could have achieved the same results. Finally, other approaches may also be effective for increasing quality of life in people with TTH. For example, significant effects were seen for bodily pain, vitality, and mental health in people with TTH following one month of adjuvant guided imagery. [38]

Conclusions

Manual therapy techniques have some influence on different aspects of quality of life in people with TTH. Considering the overall quality of life, the suboccipital inhibitory treatment was the most effective. When considering individual dimensions of quality of life, the combined treatment showed the greatest change. Separately, the application of the suboccipital inhibitory and manipulative treatment provided similar results.

References:

Auray JP. Socio-economic impact of migraine and headaches in France. CNS Drugs 2006;1:37-9.

Volcy-Gómez M.

The impact of migraine and other primary headaches on the health system and in social and economic terms.

Rev Neurol 2006;43:228-7.Felício AC, Bichuetti DB, Celso dos Santos WA, Godeiro CO, Marin LF.

Epidemiology of primary and secondary headaches in a Brazilian tertiary-care center.

Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2006,64:41-4.Serrano C, Andrés del Barrio MT, Sánchez-Palomo MJ.

Cefalea de tensión.

Medicine 2007;9:4473-6.Couppe C, Torelli P, Fuglsang-Frederiksen A, Andersen K, Jensen R.

Myofascial trigger points are very prevalent in patients with chronic tension-type headache: a double-blinded controlled study.

Clin J Pain 2007;23:23-4.Castien RF, van der Windt DA, Blankenstein AH, Heymans MW, Dekker J.

Clinical variables associated with recovery in patients with chronic tension-type headache after treatment with manual therapy.

Pain 2012;4:153:893-9.Posadzki P, Ernst E.

Spinal manipulations for tension-type headaches: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.

Complement Ther Med 2012;20:232-9.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, San-Román J, Miangolarra-Page JC.

Methodological quality of randomized controlled trials of spinal manipulation and mobilization in tension-type headache, migraine, and cervicogenic headache.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006;36:160-9.The International Headache Society.

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition.

Cephalalgia 2004;24(Suppl 1):9-160.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS).

The international classification of headache disorders, (beta version).

Cephalalgia 2013;33:629-808.Johnson EG, Landel R, Kusunose RS, Appel TD.

Positive patient outcome after manual cervical spine management despite a positive vertebral artery test.

Man Ther 2008;13:367-4.Thiel H, Rix G.

Is it time to stop functional pre-manipulation testing of the cervical spine?

Man Ther 2005;10:154-8.Toro-Velasco C, Arroyo-Morales M, Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, Cleland JA.

Short-Term Effects of Manual Therapy on Heart Rate Variability, Mood State, and

Pressure Pain Sensitivity in Patients With Chronic Tension-Type Headache:

A Pilot Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Sep); 32 (7): 527–535Fryette HH.

Occiput-Atlas-Axis.

J Am Osteopath Assoc 1936;35:353-4.Gemma V EL, Antonia GC:

Efficacy of Manual and Manipulative Therapy in the Perception of Pain and Cervical Motion

in Patients with Tension-type Headache: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial

Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2014 (Mar); 13 (1): 4—13Espí-López GV, Gómez-Conesa A, Gómez AA, Martínez JB, OlivaPascual-Vaca A.

Treatment of tension-type headache with articulatory and suboccipital soft tissue therapy: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2014;18:576-85.Vilagut G, Valderas JM, Ferrer M, Garin O, López-García E, Alonso J.

Interpretación de los cuestionarios SF-36 y SF-12 en España: com- ponentes físico y mental.

Med Clin 2008;130:726-35.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD.

A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity.

MedCare 1996;34:220-33.Alonso J, Prieto L, Anto JM.

La versión española del SF-36 Health Survey (Cuestionario de Salud SF-36): un instrumento para la medida de los resultados clínicos.

Med Clin 1995;104:771-6.Monteagudo PO, Hernando L, Palomar JA.

Reference values of the Spanish version of the SF-12v2 for the diabetic population.

Gac Sanit 2009;23:526-32.Ware JE, Gandek B, IQOLA Project Group.

The SF-36 Health Survey: development and use in mental health research and the IQOLA project.

Int J Ment Health 1994;23:49-73.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-BowkerDM, Gandek B.

How to score version 2 of the SF-12 Health Survey (with a supplement documenting version 1).

Lincoln RI: Quality Metric, Incorporated; 2002.Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, Lawrence K, Petersen S, Paice C.

A shorter form health survey: can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies?

J Public Health Medi- cine 1997;19:179-86.Stovner LJ, Zwart JA, Hagen K, Terwindt GM, Pascual J.

Epidemiology of headache in Europe.

European Journal of Neurology 2006;13:333-12.Van Ettekoven H, Lucas C.

Efficacy of physiotherapy including a craniocervical training programme for tension-type headache;a randomized clinical trial.

Cephalalgia 2006;26:983-91.Fernández de las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Cuadrado ML Miangolarra JC.

Are Manual Therapies Effec- tive in Reducing Pain From Tension-Type Headache?

Clin J Pain 2006;22:278-7.Niere K, Robinson P.

Determination of manipulative physiotherapy treatment outcome in headache patients.

Man Ther 1997;2:199-6.Anderson RE, Seniscal C.

A comparison of selected osteopathic treatment and relaxation for tension-type headaches.

Headache 2006;46:1273-7.Demirturk F, Akarcali I, Akbayrak T, Citak I, Inan L.

Results of two different manual therapy techniques in chronic tension-type headache.

The Pain Clinic 2002;14:121-8.Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Cuadrado ML, Gerwin RD.

Trigger Points in the Suboccipital Muscles and Forward Head Posture in Tension-Type Headache.

Headache 2006;46:454-6.Moraska A, Chandler C.

Pilot study of chronic tension type headache.

J Man Manip Ther 2008;16:106-12.Castien, R. F., van der Windt, D. A., Grooten, A., & Dekker, J.

Effectiveness of Manual Therapy for Chronic Tension-type Headache:

A Pragmatic, Randomised, Clinical Trial

Cephalalgia. 2011 (Jan); 31 (2): 133–143Espí-lópez G, Rodriguez-Blanco C, Oliva-Pascual-Vaca A, Beni?tezMarti?nez J.

The effect of manual therapy techniques on headache disability in patients with tension-type headache.

Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2014;50:641-7.Meredith P, Strong J, Feeney JA.

Adult attachment, anxiety, and pain self-efficacy as predictors of pain intensity and disability.

Pain 2006;123:146-54.Espí-López GV, Arnal-Gómez A, Arbós-Berenguer T, López AA, Vicente-Herrero T.

Effectiveness of physical therapy in patients with tension-type headache: literature review.

J Jpn Phys Ther Assoc 2014;17:31-8.Chaibi A, Šaltyt? Benth J, Bjørn Russell M.

Validation of Placebo in a Manual Therapy Randomized Controlled Trial.

Sci Rep 2015;5:11774Rushton A, Rivett D, Carlesso L, Flynn T, Hing W, Kerry R.

International framework for examination of the cervical region for potential of cervical arterial dysfunction prior to orthopaedic manual therapy intervention.

Man Ther 2014;19:222-8.Mannix LK, Chandurkar RS, Rybicki LA, Tusek DL, Solomon GD.

Effect of guided imagery on quality of life for patients with chronic tension-type headache.

Headache 1999;39:326-34.

Return to CHRONIC TENSION HEADACHE

Since 9-02-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |