Headache in a National Sample of American Children:

Prevalence and ComorbidityThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Child Neurol 2009 (May); 24 (5):536–543 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Tarannum M. Lateef, MD, Kathleen R. Merikangas, PhD, Jianping He, MS,

Amanda Kalaydjian, PhD, Suzan Khoromi, MD, Erin Knight, BS, Karin B. Nelson, MD

Department of Neurology, Children's National Medical Center

and George Washington University School of Medicine,

Washington, D.C., USA.

tlateef@cnmc.org

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence, sociodemographic correlates, and comorbidity of recurrent headache in children in the United States. Participants were individuals aged 4 to 18 years (n = 10,198) who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Data on recurrent and other health conditions were analyzed. Frequent or severe headaches including migraine in the past 12 months were reported in 17.1% of children. Asthma, hay fever, and frequent ear infections were more common in children with headache, with at least 1 of these occurring in 41.6% of children with headache versus 25.0% of children free of headache. Other medical problems associated with childhood headaches include anemia, overweight, abdominal illnesses, and early menarche. Recurrent headache in childhood is common and has significant medical comorbidity. Further research is needed to understand biologic mechanisms and identify more homogeneous subgroups in clinical and genetic studies.

Keywords: headache, migraine, comorbidity, prevalence

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Headache is a common complaint in children and adolescents. The most frequent type of recurrent headache in young children is migraine, [1] while the frequency of tension type headache increases in the later years of childhood. Recurrent headaches can negatively impact a child’s life in several ways, including school absences, decreased academic performance, social stigma, and impaired ability to establish and maintain peer relationships. The quality of life in children with migraine is impaired to a degree similar to that in children with arthritis or cancer. [2]

There has been limited population-based research on headache and migraine in children, particularly in the United States. Most of our knowledge regarding the prevalence and demographic correlates of migraine is derived from school-based questionnaire studies in European countries [3–6] and some from the United States. [7, 8] Prevalence estimates for headache in prepubertal children range from 2.4% to 17% for migraine and 4% to 5% for frequent or severe headache. For the postpubertal ages estimates are considerably higher, ranging from 5% to 18% for migraine and 9% to 29% for other frequent or severe headaches. Despite the impact of headache on pediatric health, only 1 population-based American study to date has examined the frequency of recurrent headache in children. [9]

Individuals who suffer from migraine or severe headaches are also diagnosed with certain other medical conditions at a higher than expected frequency. Comorbidity can significantly influence the delivery of medical care as it may confound diagnosis and provide special therapeutic challenges. No population-based study to date has systematically examined the patterns of medical comorbidity of recurrent headache or migraine in childhood. Knowledge of other biologic systems involved would not only help physicians provide better care for their patients but may also provide some clues as to the shared pathophysiology of headache and these other conditions.

This study uses the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, a complex probability sample, to examine in children the prevalence of frequent or severe headache including migraine, to examine patterns of comorbidity, and to assess the impact of childhood headaches on school absences and health care use.

There has been substantial discussion regarding the validity of the diagnostic criteria for migraine in children. [10–18] Childhood migraine tends to have shorter duration and is more often bilateral than unilateral. Headache type as assigned in childhood is not a reliable predictor of presence or type of headache disorder at later ages. [19, 20] However, recurrent or severe headaches in children are associated with recurrent headaches in later life, and their clinical significance and association with impairment suggest that they are an important entity, irrespective of the specific subtype of headache disorder.

Methods

Data were derived from the combined 6–year data from 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, a large representative sample of the US population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics to examine the health status of noninstitutionalized US citizens, children, and adults through a stratified, multistage probability sampling design. National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys over-samples low-income persons, adolescents 12 to 19 years old, and African Americans and Mexican Americans. The present study focuses on frequent or severe headache including migraine, and other medical conditions, among 4– to 18–year olds in the 3 cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination surveys conducted from 1999–2004. Detailed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey operations manuals are available on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys’ Web site. [21]

Measures

Information on headaches and other medical conditions was collected in the Medical Conditions Section of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. These questions have been widely used in National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys and prior population-based studies. This method has been shown to yield more complete and accurate reports than estimates derived from responses to open-ended questions. [22] Methodological studies in both the United States and United Kingdom have documented good concordance between such condition reports and medical records. [23–25] Data were collected through interview with the adolescent (if the individual was 16 years or older) or with a knowledgeable adult in the children’s household (if the individual was younger than 16 years).

Headaches/Migraines and other conditions

Headache status was determined by the answer to a yes/no question: “During the past 12 months, have you had frequent or severe headaches including migraine?” Medical conditions were inquired about in several ways:(1) “Has a doctor or health professional ever told you that you had ?” for high blood pressure, chicken pox, asthma, diabetes, attention deficit disorder, learning disability, and overweight;

(2) “During the past 12 months, have you had ?” for hay fever, ear infections 3 or more times, and stuttering/stammering;

(3) “During the past 3 months, have you been on treatment for ?” for anemia; and

(4) “Did you have a stomach or intestinal illness with vomiting and diarrhea in past 30 days?” Questions about health care access and use for general health and for mental health specifically were also included.

Correlates of Headaches/Migraine

Sex, age, and race/ethnicity were obtained by self-report. Age group was categorized as 4 to 5, 6 to 11, 12 to 15, and 16 to 18 years. Race/ethnicity was defined as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, other Hispanic, and other race including multiple races. Socioeconomic status was assessed by the poverty income ratio. The poverty income ratio, based on family size, is the ratio of family income to the family’s poverty threshold level, determined by the Bureau of the Census. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys calculated respondents’ poverty income ratio values using self-reported family income data. We used 3 categories such as the poverty income ratio less than 1, poverty income ratio 1 to 2, and poverty income ratio greater than or equal to 3. Poverty income ratio values less than 1 were deemed to be below the poverty threshold.

Dataset preparation and statistical analysis

Data were downloaded from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys Web site.21 Demographic, medical condition, and health care access information on individuals aged 4 to 18 years in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1999–2000, 2001–2002, and 2003–2004 were first merged horizontally within each cycle via a unique identification number (seqn), then vertically concatenated into 1 analytical dataset. After excluding missing headache information (n = 12), the analytical dataset contains 10,918 individuals aged 4 to 18 years. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.1.3 survey procedures, which use Taylor series linearization methods to accommodate sampling weights to account for stratification and clustering of the multistage National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys sampling design in the calculation of prevalence estimates, standard errors, 95% confidence intervals, unadjusted or adjusted odds ratios, and test statistics.

For estimates in the 6–year pooled National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys data, a 6–year weight variable was created by assigning 2/3 of the 4–year weight for 1999–2002 if the person was sampled in 1999–2002 and assigning 1/3 of the 2–year weight for 2003–2004 if the person was sampled in 2003–2004. The sampling weights are inversely proportional to the probability of selection into the sample and are therefore interpretable as the number of individuals in the target population that each sample participant is estimated to represent. Weighted prevalence rates and standard errors were calculated for headache and comorbidity. Survey logistic regression models were used to estimate the association between headache and comorbid conditions, controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and poverty income ratio. For all of the analyses, a two-sided test with P values <.05 was considered statistically significant. [26]

Results

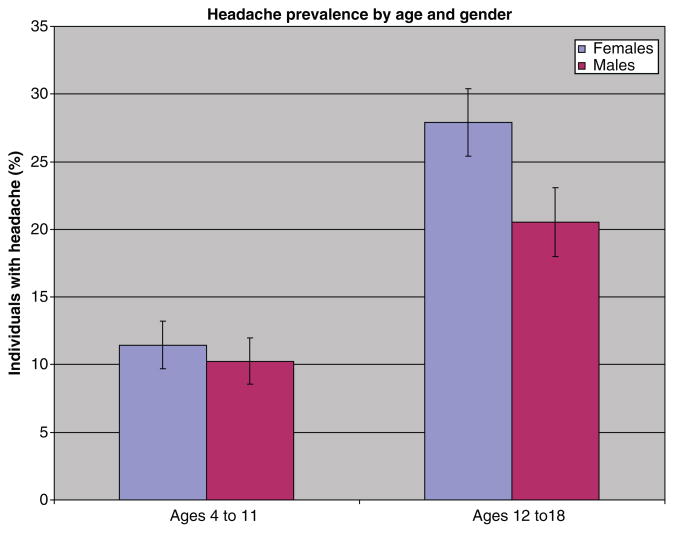

Figure 1

Table 1

Table 2 Among 10,918 individuals aged 4 to 18 surveyed in 1999–2004, 17.1% were reported to have experienced frequent or severe headaches including migraine in the previous 12 months (Table 1). The prevalence of headache rose with increasing age. Before puberty, rates of headache were comparable in boys and girls, but after the age of 12, girls with headache outnumbered boys (Figure 1). The highest headache prevalence — 27.4% — was observed in girls aged 16 to 18 years. Over the 3 2–year periods of the study, controlling for sex, race, and poverty income ratio, there was no significant trend in headache prevalence in the total or in the youngest subgroup.

Examined by self-reported race and ethnic group, frequent or severe headache rates were highest in non-Hispanic black children and lowest in Mexican Americans. Reported headache frequency rose with decreasing family income level and was highest in those classified by the poverty index ratio as relatively low in income.

Children with headaches more often had other medical conditions, including asthma, hay fever, or frequent ear infections, but not chickenpox (Table 2). Of children with headache, 41.6% experienced at least 1 of these conditions (adjusted odds ratio 2.2, confidence interval 1.9–2.6). Children with headache were 3.2 times more likely to have 2 of the 3 of these conditions (confidence interval 2.4–4.3), and 13.6 times more likely to have all 3 (confidence interval 4.8–38.4). When stratified by age, children aged 4 to 11 years had the strongest association with any or all of these conditions.

Other conditions that were more frequently reported in children with frequent or severe headaches were attention deficit disorder, learning disability, and stuttering or stammering. Anemia, overweight, and stomach or intestinal illnesses were more often observed in children with headache, but not high blood pressure or diabetes. A greater number of children with headache had a history of more than 1 of these conditions compared with their nonheadache counterparts. More girls with headache than without had experienced their first menstrual period before the age of 12 years, and this cannot be explained by children with frequent or severe headaches being more overweight, as early menarche and overweight were not significantly associated (odds ratio adjusted for race and poverty income ratio, 1.4, confidence interval 0.6–3.6).

Table 3 Consistent with their higher frequencies of several comorbid conditions, children with headaches had more often missed school and had received health care more often and more recently than children without headaches (Table 3). They were also twice as likely to have seen a mental health professional. A larger but still small proportion had been admitted to a long-term care facility, and more had household members who were in a care facility.

Discussion

Frequent or severe headaches including migraine were reported in 4% of 4– and 5–year olds, with prevalence increasing to 25% in the later teen years. Children who suffer from recurrent headaches are more likely to have other medical conditions and more frequent school absences compared to children without headaches. It is worth noting that frequent or severe headaches including migraine were reported more frequently in African American children and least often reported in Mexican American youth. The greater frequency of recurrent headaches in lower income households and among African-American youth compared to other ethnic subgroups is of particular concern because of the well-recognized barriers to adequate health care among disadvantaged subgroups in the United States.

Although there is substantial knowledge about the frequency, distribution, and correlates of headache and migraine in European countries, there are nearly no population-based data on the prevalence of migraine or recurrent headaches in children in the United States. One recent study using National Health Interview Survey data helped to fill this gap by presenting information on the magnitude, sociodemographic correlates, and psychosocial elements of headache in a very large sample of US youth. [9] Headache prevalence estimates in the present study were considerably higher than those in the NHIS survey and more comparable to previous studies. [1, 3–8] Also, the NHIS survey results are based on data from a single 1–year period, whereas the present study establishes stable rates of headache for 3 consecutive 2–year periods.

Children with recurrent headaches often have other medical problems and higher rates of health care use. The fact that socioeconomically disadvantaged children are particularly prone to headaches further emphasizes the need for early identification of these children to minimize long-term consequences.

Medical conditions previously reported with increased frequency among adult persons with migraine or headache include asthma and atopic disorders, [27–30] stroke and cardiovascular risk factors, sleep problems, motion sickness, epistaxis, and, in women of reproductive age, menorrhagia. In agreement with these studies in adults, we found that children with headaches had other medical conditions more often than children without headaches, with a range of 40% to 300% higher rates of several conditions assessed. In a parallel study of US adults in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, persons with headache also had increased rates of health care use and were more likely than those without headache to describe their health as “fair or poor” (Kalaydjian and Merikangas, unpublished). Together, these results suggest an association between headaches and both comorbidity and increased health care use that persists throughout the life course.

The strongest associations between medical conditions and headache emerged for asthma, hay fever, and frequent ear infection, at least 1 of these occurring in 41.6% of children with headache versus 25.0% of children free of headache (P < .0001). Being overweight, anemia and stomach or intestinal illnesses also occurred more often in children with headache but did not cluster as did asthma, hay fever, and frequent ear infection. Reports of an association between migraine with asthma and other allergic disorders have been reported in clinical samples of headache and allergic disorders for several decades. [28, 30] In fact, the consistent evidence relating headache disorders and migraine with asthma and allergies led 1 observer to refer to asthma as “pulmonary migraine.” [31] The results of the present study confirm those of prior population-based samples of adults in Norway [32] and the United Kingdom, [28, 33] thereby suggesting that migraine-allergic comorbidity is not an artifact of treatment seeking or Berkson’s bias. [34]

Among conditions previously noted to be associated with recurrent headache, psychosocial and behavioral disturbances have been the most extensively studied, both in children and in adults, and in tension type headaches as well as migraine. [35–38] Our results on the association between headaches or migraine in children and learning disabilities, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and stuttering or stammering are in agreement with a recent study using data from the National Health Interview Survey, [9] which represents the most comparable sample to ours in the literature.

The 2 chief classes of explanations for comorbidity include common etiologic pathways underlying the 2 conditions, or “causal” mechanisms in which the development of an index disorder or its treatment increases the risk of the occurrence of the comorbid condition. [38] For example, the inflammatory mediators underlying atopic disorders, particularly mast cells, may underlie the development of headaches. [39, 40] Alternatively, headaches could be a secondary manifestation of allergies, or a side effect of its treatment. The cross-sectional design of the present study did not permit our evaluation of these potential explanations. Prior studies seeking an inflammatory basis for migraine have looked at various immune mediators, including complement and immunoglobulins, histamine, cytokines, and immune cells, but failed to establish a consistent role for any 1 of these among migraineurs. [41] However, it is possible that inflammation is an important component in a subset of migraineurs, perhaps genetically determined, who also manifest other atopic diseases. Future prospective studies are needed to examine immune biomarkers in this subset of headache sufferers.

As measured in National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, severe or recurrent headache does not distinguish between migraine and other frequent or severe headache types. As demonstrated in many studies, the International Classification of Headache Disorders–1 was inadequate at distinguishing the primary headache syndromes in childhood. With publication of the International Classification of Headache Disorders–II in 2004, the sensitivity of diagnosis of migraine without aura in children improved from 21% to 53%, still missing almost half of pediatric migraine. [42] Although the lack of distinction between migraine and other headache types is a limitation of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys data with respect to postpubertal children and adolescents, it is far less a limitation in consideration of young children.

This is because headaches in early childhood are not only difficult to classify but also continuously evolve over time. [19] The likelihood of migraine at puberty is practically equal among children who present with tension-type headache or migraine at 6 years of age. [20] In either age group, knowledge of other conditions that occur with increased frequency in youth with recurrent or severe headache or migraine can lead to research to examine biologic mechanisms underlying the associations, aid in the delineation of more homogenous subgroups for clinical and genetic studies, and improve clinical management.

The strengths of this study include the large and nationally representative sample of a wide age range of children, the stability of headache rates over 6 annual waves of independent samples, and the breadth of correlates of chronic conditions included in the survey. Moreover, few population-based studies of headache have investigated comorbidity with a range of medical disorders, especially in the pediatric age group.

Conclusion

Most of the literature on comorbid conditions in children with headache has stressed psychological factors, and indeed these may be important as causes or consequences of headache, and need management. However, children with severe or frequent headaches or migraine are a multiproblem group. Asthma, hay fever, and frequent ear infections, separately or together, are especially overrepresented in children with headache. A fuller view of the range of problems facing children with recurrent headache may help in providing care, in considering biologic mechanisms, and in identifying more homogeneous subgroups for clinical and genetic studies. [43]

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

References:

Raieli V, Eliseo M, Pandolfi E, et al.

Recurrent and chronic headaches in children below 6 years of age.

J Headache Pain. 2005;6:135–142Powers S, Patton S, Hommel KA, Hershey AD.

Quality of life in childhood migraine: clinical impact and comparison to other chronic illnesses.

Pediatrics. 2003;112:1–5.Bille B.

Migraine in school children. A study of the incidence and short-term prognosis, and a clinical, psychological

and electroencephalographic comparison between children with migraine and matched controls.

Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1962;136:1–151.Deubner DC.

An epidemiologic study of migraine and headache in 10–20 year olds.

Headache. 1977;17:173–180.Sillanpaa M.

Changes in the prevalence of migraine and other headache during the first seven school years.

Headache. 1983;23:15–19.Sillanpa M.

Prevalence of headache in prepuberty.

Headache. 1983;23:10–14.Linet MS, Stewart WF, Celentano DD, Ziegler D, Sprecher M.

An epidemiologic study of headache among adolescents and young adults.

JAMA. 1989;261:2211–2216.Stewart WF, Linet MS, Celentano DD, Van Natta M, Siegler D.

Age and sex-specific incidence rates of migraine with and without visual aura.

Am J Epidemiol. 1991;34:1111–1120.Strine TW, Okoro CA, McGuire LC, Balluz LS.

The associations among childhood headaches, emotional and behavioral difficulties, and health care use.

Pediatrics. 2006;117:1728–1735.Mortimer MJ, Jay J, Jaron A.

Epidemiology of headache and childhood migraine in an urban general practice using Ad hoc,

Vahlquist and IHS criteria.

Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34:1095–1101.Winner P, Hershey AD.

Epidemiology and diagnosis of migraine in children.

Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2007;11:375–382.Senbil K, Gurer YK, Aydin OF, Rezaki B, Inan L.

Diagnostic criteria of pediatric migraine without aura.

Turk J Pediatr. 2006;48:31–37.Gallai V, Sarchielli P, Carboni F, Benedetti P, Mastropaolo C, Puca F.

Applicability of the 1988 IHS criteria to headache patients under the age of 18 years attending

21 Italian headache clinics. Juvenile Headache Collaborative Study Group.

Headache. 1996;35:146–153.Wober-Bingol C, Wober C, Wagner-Ensgraber C, et al.

IHS criteria for migraine and tension-type headache in children and adolescents.

Headache. 1996;36:231–238.Maytal J, Young M, Shechter A, Lipton RB.

Pediatric Migraine and the International Headache Society (IHS) Criteria.

Neurology. 1997;48:602–607.Gherpelli Jl, Nagae Poetscher LM, Souza AM, et al.

Migraine in childhood and adolescence. A critical study of the diagnostic criteria

and of the influence of age on clinical findings.

Cephalalgia. 1998;18:333–341.Hamalainen ML, Hoppu K, Santavuori PR.

Effect of age on the fulfillment of IHS criteria for migraine in children at a headache clinic.

Cephalalgia. 1995;15:405–409.Battistella PA, Fiumana E, Binelli M, et al.

Primary headaches in preschool age children: clinical study and follow-up in 163 patients.

Cephalalgia. 2005;26:162–171.Brna P, Dooley J, Gordon K, Dewan T.

The prognosis of childhood headache.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1157–1160.Virtanen R, Aromaa M, Rautava, et al.

Changing headache from preschool age to puberty. A controlled study.

Cephalalgia. 2007;27:294–303.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [Accessed January 11, 2007].

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm

Updated November 26, 2008.Knight M, Stewart-Brown S, Fletcher L.

Estimating health needs: the impact of a checklist of conditions and quality of life measurement

on health information derived from community surveys.

J Public Health Med. 2001;23:179–186.Baker M, Stabile M, Deri C.

NBER Working Paper. What do self-reported, objective measures of health measure? p. 8419Edwards WS, Winn DM, Kurlantzick V, et al.

Evaluation of national health interview survey diagnostic reporting.

National Center for Health Statistics.

Vital Health Stat. 1994;2:120.Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D, et al.

Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI): development and validation of a patient reported

assessment of severity of gastroparesis symptoms.

Qual Life Res. 2004;13:833–844.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [Accessed January 11, 2007].

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/nhanes2003-2004/nhanes03_04.htm

Updated January 13, 2009.Davey G, Sedgwick P, Maier W, Visick G, Strachan DP, Anderson HR.

Association between migraine and asthma: matched case-control study.

Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:723–727Ozge A, Ozge C, Ozturk C, et al.

The relationship between migraine and atopic disorders—the contribution of pulmonary function

tests and immunological screening.

Cephalalgia. 2005;6:172–179.Mortimer MJ, Kay J, Gawkrodger DJ, Jaron A, Barker DC.

The prevalence of headache and migraine in atopic children: an epidemiologic study in general practice.

Headache. 1993;33:427–431.Ku M, Silverman B, Prifti N, Ying W, Persaud Y, Schneider A.

Prevalence of migraine headaches in patients with allergic rhinitis.

Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:226–230.Tucker GF., Jr

Pulmonary migraine.

Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:671–676.Aamodt AGH, Stovner LJ, Langhammer A, Hagen K, Zwart J-A.

Is headache related to asthma, hay fever, and chronic bronchitis?: the Head-HUNT study.

Headache. 2007;47:204–212.Strachan DP, Butland BK, Anderson HR.

Incidence and prognosis of asthma and wheezing illness from early childhood to age 33 in a national British cohort.

BMJ. 1996;312:1195–1199Berkson J.

Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data.

Biometrics. 1946;2:47–53.Merikangas KR, Risch NJ, Merikangas JR, Weissman MM, Kidd KK.

Migraine and depression: association and familial transmission.

Psychiatry Res. 1988;22:119–129.Merikangas KR, Angst J, Isler H.

Migraine and psychopathology: results of the Zurich Cohort Study of Young Adults.

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:849–853.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P.

Migraine, psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts: an epidemiologic study of young adults.

Psychiatry Res. 1991;37:11–23.Breslau N, Merikangas K, Bowden CL.

Comorbidity of migraine with major affective disorders.

Neurology. 1994;44(suppl 7):S17–S22.Levy D, Burstein R, Kainz V, Jakubowski M, Strassman AM.

Mast cell degranulation activates a pain pathway underlying migraine headache.

Pain. 2007 Apr 23;Zhang X, Strassman AM, Burstein R, Levy D.

Sensitization and activation of intracranial meningeal nociceptors by mast cell mediators.

J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007 May 4;Kemper RHA, Meijler WJ, Korf J, Ter Horst GJ.

Migraine and function of the immune system: a meta-analysis of clinical literature

published between 1966 and 1999.

Cephalagia. 2001;21:549–557.Lima MM, Padula NA, Santos LC, Oliveira LD, Agapejev S, Padovani C.

Critical análysis of the International classification of headache disorders diagnostic criteria

(ICHD I-1988) and (ICHD II-2004), for migraine in children and adolescents.

Cephalalgia. 2007;25:1042–1047.Anttila V, Kallela M, Oswell G, et al. Trait components provide tools to dissect the genetic susceptibility to migraine.

Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:85–88

Return to HEADACHE

Return to PEDIATRICS

Since 1-19-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |