Perceptions of Chiropractic Care Among Women With Migraine:

A Qualitative Substudy Using a Grounded-Theory FrameworkThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2021 (Feb); 44 (2): 154–163 ~ FULL TEXT

Julie P. Connor, BS, Carolyn Bernstein, MD, Karen Kilgore, PhD, Kamila Osypiuk, MS, Matthew Kowalski, DC, Peter M. Wayne, PhD

Osher Center for Integrative Medicine,

Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital,

Boston, Massachusetts

Objective: The purpose of this study was to characterize expectations, attitudes, and experiences of individuals with migraine who were randomly assigned to receive chiropractic care delivered within a randomized controlled trial in a hospital-based integrative care center.

Methods: This qualitative substudy was conducted as a part of a 2-arm pilot pragmatic randomized controlled trial investigating a multimodal model of chiropractic care for women with episodic migraine (4-13 migraines per month). Women were randomly assigned to chiropractic care (10 sessions over 14 weeks) plus enhanced usual care vs enhanced usual care alone. Semistructured interviews were conducted at baseline and 14-week follow-up with 15 randomly selected participants from the 29 participants randomized to the chiropractic group. Qualitative analysis was performed by 2 independent reviewers using a constant comparative method of analysis for generating grounded theory.

Results: Integrating baseline and follow-up interviews, 3 themes emerged: over the course of treatment with chiropractic care, participants became more aware of the role of musculoskeletal tension, pain, and posture in triggering migraine; participants revised their prior conceptions of chiropractic care beyond spinal manipulation; and participants viewed the chiropractor-patient relationship as an essential and valuable component to effectively managing their migraines.

Conclusion: In this qualitative study, women with episodic migraine after receiving comprehensive chiropractic care described chiropractic as a multimodal intervention where they learned about musculoskeletal contributions to migraine, discovered new ways to affect their symptoms, and developed a collaborative patient-practitioner relationship. The results of this study provide insights into perceptions of chiropractic care among women with migraine and suggestions for future trials.

Keywords: Chiropractic; Complementary Therapies; Female; Integrative Medicine; Migraine Disorders; Qualitative Research.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

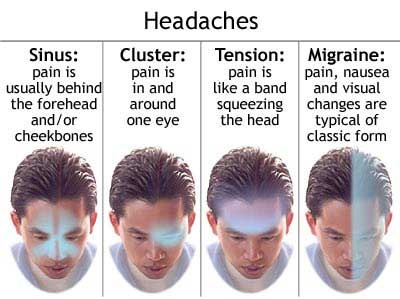

Migraine, a chronic intermittent headache disorder, now ranks globally in the top 5 for years lived with disability. [1] Approximately 15% of the general US population experiences migraine, with women afflicted approximately 3 times more frequently than men. [2] Migraine symptoms—lasting 4 to 72 hours and characterized by throbbing pain, nausea, and sensitivity to light and sound—often interfere with daily activities. Migraineurs often seek treatment to lessen the duration and severity of the pain and other symptoms. [3] A variety of medications used as first-line treatments may have intolerable side effects or precipitate migraine chronification. [4] Consequently, individuals who experience migraine attacks often search for alternative treatments, including holistic or integrative approaches. [5]

One potentially promising nonpharmacologic option, because of the comorbidity of migraine and musculoskeletal complaints, may be chiropractic care. Three out of 4 individuals with migraine experience neck pain [6]; migraineurs also report musculoskeletal complaints including muscle tension and jaw dysfunction. [7, 8] National surveys indicate that a significant proportion of migraineurs seek complementary and integrative therapies including chiropractic care. [9, 10] However, few report seeking chiropractic care specifically for headaches,9 and very little is known about individuals’ perceptions and experiences around migraine-related chiropractic treatment. Additionally, there is scant scientific evidence demonstrating chiropractic efficacy for migraine headaches. [11]

To inform the design of a future trial, and to understand factors that might impact posttrial implementation and dissemination, we conducted a qualitative substudy using a grounded-theory framework. The purpose of this study was to characterize expectations, attitudes, and experiences of patients randomly assigned to receive chiropractic care delivered within the study's setting, which was a hospital-based integrative care center.

Discussion

Migraine is a highly prevalent and debilitating condition for which patients commonly seek complementary and integrative therapies, including chiropractic. [10] This study sought to understand patients’ perceptions of their experiences with chiropractic care for migraines and represents the first qualitative study addressing this topic. Our findings indicate that over the course of their chiropractic care, participants increased their awareness of potential factors contributing to their migraines and learned new management strategies. Participants specifically became more aware of the extent to which musculoskeletal factors contributed to their migraines. They also came to view chiropractic care as a multimodal intervention to treat their migraines and promote general well-being. Over the treatment course, participants valued the supportive and collaborative relationship with their chiropractors, which enhanced their self-efficacy in managing their migraines. Although no prior studies have qualitatively characterized migraineurs’ encounter with chiropractic, prior qualitative studies of both chiropractic for other pain conditions and migraineurs’ encounters with other therapeutic approaches provide valuable context for the 3 main emergent themes.

The first theme emerging from participant interviews was an increased awareness of the roles of musculoskeletal tension, postural issues, and the physical manifestation of stress as contributing factors to migraines. The majority of chiropractic qualitative studies have been conducted in the context of chronic back or neck pain, [21, 24] where the role of musculoskeletal issues as contributors to pain and disability are more obvious than in our migraine population. However, some studies report parallel findings to ours: chiropractic care increasing awareness of the relationship between posture, stress, and pain; affording a credible explanation of pain; and providing tools for long-term management. [21–25] Our participants reported awareness of triggers such as hormonal cycles and weather changes which are not within their control, and therefore made it difficult to manage their migraines. They also noted other factors, such as food, sleep cycles, excessive sound, or types of lighting, which were sometimes controllable triggers. In this study, participants became more aware of additional factors they could control, specifically posture, stress, and tension. Echoing other studies of chiropractic, patients appreciated the chiropractors’ detailed descriptions of the musculoskeletal contributors to their pain and simple exercises to target those areas. [22–25] This greater awareness of the links between musculoskeletal factors and migraine occurrence parallels a broader appreciation in the wider migraine clinical community of an association between neck tension or pain and migraine occurrence, [6–8] including emerging models of migraine pathophysiology which implicate the trigeminocervical complex. [26, 27] The relation between musculoskeletal health and migraine is a valuable area for further research into migraine etiology and treatment targets.

The second emergent theme in our study relates to participants’ changing perceptions of the chiropractic profession throughout the course of the study. Initially, most participants had a positive impression of chiropractic but had limited knowledge of the scope of chiropractic care. Most participants had associated chiropractic specifically with spinal manipulation. A few expressed reservations regarding the safety of neck manipulations. After the chiropractic intervention, participants were surprised by the comprehensive package of care provided by the chiropractors, including soft tissue manipulation, lifestyle recommendations, fitness coaching, and nutritional advice. [28–30] Their view of chiropractic extended beyond spinal manipulation. They learned that the scope of chiropractic practice includes education regarding long-term maintenance for the musculoskeletal system to reduce or avoid pain and improve posture and functional fitness.

Narrower perceptions of chiropractic care in our study parallel those of the US population. In a 2015 national survey, about 61% of respondents believed that chiropractic care was effective at treating neck and back pain; however, a significant proportion of respondents reported that they did not have a “good understanding” of what chiropractors do. [31] This perception is reinforced by chiropractic clinical research, which has emphasized focused explanatory studies evaluating specific spinal manipulation techniques, [32] in contrast to pragmatic interventions evaluating multimodal models of chiropractic care. [11, 33] More generally, changes in perception among participants in our study related to the chiropractic scope of care reflect debates within the evolving chiropractic profession regarding the shifting perception of chiropractic as a set of techniques versus a holistic, multimodal approach to care.34

The scope of chiropractic training, licensure, and practice is not widely recognized. Many members of the general public and health care practitioners commonly equate chiropractic care solely with the treatment intervention of spinal manipulation, essentially viewing the profession as a treatment technique rather than a system of health care. [35–37] This has, perhaps, been fostered by some chiropractors focusing their practice on this single intervention. The multimodal approach taken in this study, arrived at using a modified Delphi expert-panel approach, [13] was intended to more accurately reflect the training, national certification, and statutory scope of practice utilized by licensed Massachusetts chiropractors.

The third theme extracted from our interviews was the value of the patient–practitioner relationship and how this fostered a sense of self-efficacy and self-care. Overall, participants had a positive view of the chiropractic care they received and described their relationships with the chiropractors as reciprocal and collaborative. They expressed the importance of having a trusted provider listen to their report of symptoms, adapt approaches based on their feedback, create a personalized approach, and teach them about the multifaceted nature of their condition. Participants explained that managing the complexity and chronicity of migraines was facilitated by trusting and reciprocal relationships with their health care providers. They also valued the focused, compassionate care provided by the chiropractors, occurring in 20–minute weekly sessions.

In prior qualitative studies of chiropractic care for other pain conditions, participants have also emphasized the value of the chiropractor–patient relationship. [21, 24, 25] Individuals with chronic pain appreciate that chiropractors spend time to listen to them, validate their pain—something they have not always received from other practitioners—and work with them to create an individualized approach. [24, 25] One scholarly analysis of the chiropractic profession suggests that the high levels of patient satisfaction and patient–practitioner alliance reported by chiropractic patients may stem from encounters that combine touch-based diagnosis and treatments along with tools that support patient self-care and empowerment. [38] Given the growing interest in understanding and enhancing the therapeutic power of the patient–practitioner relationship in health care, future studies comparing and contrasting these contextual effects in migraine patients receiving care from chiropractors vs other providers would be an interesting area for further study.

The findings of this qualitative study parallel clinical outcomes in its parent randomized trial, which—although only a pilot study—preliminarily support clinically meaningful improvements in migraine days and disability. [12]

A secondary goal of this study was to inform the design of a future trial on chiropractic for migraine and to understand factors that might impact implementation and dissemination. The participants reported learning more about their musculoskeletal migraine triggers, including a connection between neck pain and migraine. Neck pain and musculoskeletal tension have been associated with migraine previously. [6] The results from our study suggest the need to further investigate the role of neck pain in migraine pathogenesis and the efficacy of neck-pain treatments, including chiropractic care, in mitigating both neck pain and migraine. This could involve including more specific instruments for tracking neck pain alongside instruments assessing migraine symptoms and determining association. Additionally, neuroimaging before and after chiropractic treatment could highlight whether there is a neural signature for the effect of chiropractic on migraine and pain in general.

In the parent trial, participants received 10 sessions of chiropractic care over 14 weeks. In the qualitative component, they expressed differing opinions on the frequency of treatments. Many would have preferred fewer treatments. A future trial should examine whether there is a dose response to chiropractic by varying the number of visits that participants receive. Additionally, to better resemble clinical care, a future trial could reassess treatment frequency midway through the sessions depending on individual participant progress.

Finally, many participants rated accessing the clinic as the worst part of the study. A future trial should utilize multiple sites of chiropractic care, both to increase the generalizability of the results and to reduce the burden for accessing care.

Limitations

We explored the experiences of 15 individuals—predominantly white, younger women with episodic migraines—and thus our results cannot be generalized to the larger population of individuals diagnosed with migraine. Additionally, the study sample was from only 1 part of the United States, and may not generalize to individuals with migraine in other parts of the country and the world. Although our model of care was developed and validated using an expert panel, [13] the interventions were delivered by only 2 chiropractors based in a tertiary care hospital setting, so their approach may not be representative of the care delivered across the chiropractic profession. In addition, the study protocol prespecified the duration and frequency of the treatment sessions. Because of limitations from the initial IRB regarding participant contact after study completion, the research team was unable to contact participants to review their interview transcripts or findings from the study. The analysis procedure consisted of 2 researchers (J.P.C., K.K.) comparing and contrasting the interviews, identifying themes from them, and then choosing exemplary quotes. Other researchers may have come up with different themes or exemplary quotes. Researcher bias was mitigated by regular consultations with the larger research team.

Conclusion

In this qualitative study, participants described chiropractic as a multimodal intervention where they learned about musculoskeletal contributions to migraine, discovered new ways to affect their symptoms, and developed a collaborative patient–practitioner relationship. The results of this study provide insights into perceptions of chiropractic care among women with migraine and suggestions for future trials.

References:

Global Burden of Disease Headache Collaborators

Global, Regional, and National Burden of Migraine and Tension-type Headache,

1990-2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016

Lancet Neurol. 2018 (Nov); 17 (11): 954–976Burch R Rizzoli P Loder E

The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States:

figures and trends from government health studies.

Headache. 2018; 58: 496-505Diamond S Bigal ME Silberstein S Loder E Reed M Lipton RB

Patterns of diagnosis and acute and preventive treatment for migraine

in the United States: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study.

Headache. 2007; 47: 355-363Lipton RB Serrano D Nicholson RA Buse DC Runken MC Reed ML

Impact of NSAID and triptan use on developing chronic migraine:

results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study.

Headache. 2013; 53: 1548-1563Befus DR Hull S Strand de Oliveira J Schmidler GS Weinberger M Coeytaux RR

Nonpharmacological Self-Management of Migraine Across Social Locations:

An Equity-Oriented, Qualitative Analysis

Glob Adv Health Med 2019 (Jun 13); 8: 2164956119858034Ashina S, Bendtsen L, Lyngberg AC, Lipton RB, Hajiyeva N, Jensen R.

Prevalence of Neck Pain in Migraine and Tension-type Headache:

A Population Study

Cephalalgia. 2015 (Mar); 35 (3): 211–219Plesh O Adams SH Gansky SA

Self-reported comorbid pains in severe headaches or migraines in a US national sample.

Headache. 2012; 52: 946-956Giffin NJ Ruggiero L Lipton RB et al.

Premonitory symptoms in migraine: an electronic diary study.

Neurology. 2003; 60: 935-940Wells RE Bertisch SM Buettner C Phillips RS McCarthy EP

Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults with migraines/severe headaches.

Headache. 2011; 51: 1087-1097Wells RE Beuthin J Granetzke L

Complementary and integrative medicine for episodic migraine:

an update of evidence from the last 3 years.

Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019; 23: 10Rist PM, Hernandez A, Bernstein C, et al.

The Impact of Spinal Manipulation on Migraine Pain and Disability:

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2019 (Apr); 59 (4): 532–542Rist PR, Bernstein C, Kowalski M, et al.

Chiropractic care for migraine: a pilot randomized clinical trial.

Cephalalgia. in pressWayne PM Bernstein C Kowalski M et al.

The Integrative Migraine Pain Alleviation Through Chiropractic Therapy

(IMPACT) Trial: Study Rationale, Design and Intervention Validation

Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2020 (Jan 22); 17: 100531Charmaz K

Constructing Grounded Theory.

2nd ed. Sage, Los Angeles, CA2014Creswell JW Creswell JD.

Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches.

5th ed. Sage, Los Angeles, CA2017Tong A Sainsbury P Craig J

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ):

a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups.

Int J Qual Health Care. 2007; 19: 349-357Seidman I

Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences.

3rd ed. Teachers College Press, New York, NY2006Bernard HR

Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches.

4th ed. AltaMira Press, Lanham, MD2006Corbin JM Strauss A

Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria.

Qual Sociol. 1990; 13: 3-21Glaser BG Strauss AL

The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research.

Aldine, Chicago, IL1967Eaves ER, Sherman KJ, Ritenbaugh C, et al.

A Qualitative Study of Changes in Expectations Over Time Among

Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Seeking Four CAM Therapies

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015 (Feb 5); 15: 12Maiers M, Hondras MA, Salsbury SA, Bronfort G, Evans R.

What Do Patients Value About Spinal Manipulation and Home Exercise for

Back-related Leg Pain? A Qualitative Study Within a Controlled Clinical Trial

Manual Therapy 2016 (Dec); 26: 183–191Sadr S, Pourkiani-Allah-Abad N, Stuber KJ

The Treatment Experience of Patients With Low Back Pain During

Pregnancy and Their Chiropractors: A Qualitative Study

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2012 (Oct 9); 20 (1): 32Stilwell P Harman K “I didn't pay her to teach me how to fix my back”: a focused ethnographic study exploring chiropractors’ and chiropractic patients’ experiences and beliefs regarding exercise adherence. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2017; 61: 219-230

Cherkin, D.C. and MacCornack, F.A.

Patient Evaluations of Low Back Pain Care From

Family Physicians and Chiropractors

Western Journal of Medicine 1989 (Mar); 150 (3): 351–355Goadsby PJ

Pathophysiology of migraine.

Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012; 15: S15-S22Bartsch T, Goadsby PJ

Increased responses in trigeminocervical nociceptive neurons

to cervical input after stimulation of the dura mater.

Brain. 2003; 126: 1801-1813Vining R, Mathers S

Chiropractic medicine for the treatment of pain in the rehabilitation patient.

in: Carayannopoulos A Comprehensive Pain Management in the Rehabilitation Patient.

Springer, Cham, Switzerland 2017: 575-596Christensen M Hyland J Goertz C Kollasch M

Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2015

National Board of Chiropractic Examiners, Greely, CO 2015Coulter I Adams A Coggan P Wilkes M Gonyea M

A Comparative Study of Chiropractic and Medical Education

Altern Ther Health Med. 1998 (Sep); 4 (5): 64–75Weeks WB, Goertz CM, Meeker WC, Marchiori DM.

Public Perceptions of Doctors of Chiropractic: Results of a National Survey and Examination

of Variation According to Respondents' Likelihood to Use Chiropractic, Experience With

Chiropractic, and Chiropractic Supply in Local Health Care Markets

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Oct); 38 (8): 533–544Alvarenga BAP Fujikawa R João F Lara JPR Veloso AP

The effects of a single session of lumbar spinal manipulative therapy

in terms of physical performance test symmetry in asymptomatic athletes:

a single-blinded, randomised controlled study.

BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018; 4: e000389Leininger B Bronfort G Haas M et al.

Spinal rehabilitative exercise or manual treatment for

the prevention of tension-type headache in adults.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; 2016 (CD012139)Leboeuf-Yde C, Innes SI, Young KJ, Kawchuk GN, Hartvigsen J

Chiropractic, One Big Unhappy Family: Better Together or Apart?

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2019 (Feb 21); 27: 4Chang M

The Chiropractic Scope of Practice in the United States: A Cross-sectional Survey

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014 (Jul); 37 (6): 363–376Schneider M, Murphy D, Hartvigsen J.

Spine Care as a Framework for the Chiropractic Identity

Journal of Chiropractic Humanities 2016 (Dec); 23 (1): 14–21Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Professions or Modalities? Policy Implications

for Coverage, Licensure, Scope of Practice, Institutional Privileges, and Research

Institutional Privileges, and Research.

Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2015.Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM

Chiropractic: Origins, Controversies, and Contributions

Arch Intern Med 1998 (Nov 9); 158 (20): 2215–2224

Return to MIGRAINE HEADACHE

Since 10-24-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |