Patient Experience and Satisfaction With Chiropractic Care:

A Systematic ReviewThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Patient Experience 2024 (Dec 25): 11:23743735241302992 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Dave Newell, PhD • Michelle M Holmes, PhD

AECC School of Chiropractic,

Health Sciences University,

Bournemouth, UK.

Despite numerous studies that measure satisfaction in patients undergoing chiropractic care, these have not yet been systematically summarized. The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review of existing literature to identify factors that contribute to high levels of satisfaction in chiropractic care. A comprehensive search was conducted to identify quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies exploring patient experience with chiropractic care. Forty-three studies were included in the review. The findings showed that patient satisfaction was consistently high in comparison to other professions. The review identified key factors that contribute to patient experience, which were not limited to clinical outcomes, but also the clinical interaction and clinician attributes. The findings of this review provide a core insight into patient experience, identifying both positive and negative experiences not just within chiropractic care but in the wider healthcare sector. Further work should explore factors that impact patient satisfaction and how this understanding may further improve healthcare to enhance patient experience.

Keywords: chiropractic; pain management; patient experience; patient satisfaction.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

The rapidly expanding health workforce encompasses a diverse array of professions beyond traditional medicine, to meet the multifactorial healthcare needs of national populations. Chiropractic is a statutorily regulated profession, with chiropractors qualified to deliver a package of care, including pain education, self-management advice, manipulation and manual therapy treatments, and tailored exercise recommendations. [1] Chiropractors identify as spinal health experts, focusing on improving function in the neuromuscular system and overall health and wellbeing of patients, predominately seeing patients with musculoskeletal conditions. [2, 3] Contemporary meta-analyses support the use of spinal manipulative therapy, a key component of chiropractic care, for such conditions. [4, 5] However, there is a shift to measure the impact of healthcare provision in a more patient-centered manner, considering not only clinical outcomes, but also patient experience and satisfaction measures as key metrics in determining quality of care.

Previous reviews synthesizing existing research on patient satisfaction identified that patients tend to report high levels of satisfaction with chiropractic care. [6] In addition, patients are often more satisfied with chiropractic care compared to encounters with other healthcare professionals. Despite the overwhelming support for chiropractic care, there is limited understanding of the drivers for these high levels of patient satisfaction. One explanation for the high levels of satisfaction, is around the pivotal role that effective communication plays in patient care, [6] with clinicians communication to identify their patients’ main concerns and other information as key. [7, 8] However, while communication is recognized as a potential driver of patient satisfaction in chiropractic care, there is limited exploration of this factor.

Despite the presence of numerous studies that measure patient experience and satisfaction within chiropractic care, these valuable insights have not yet been systematically gathered and comprehensively explored. Understanding patient experiences is thus important in the context of a value-based healthcare paradigm as a measure of the value of an intervention over and above traditional clinical outcomes. [9] The aim of this review was to identify, categorize, and summarize the published literature pertaining to the experiences and satisfaction levels of patients undergoing chiropractic care.

Method

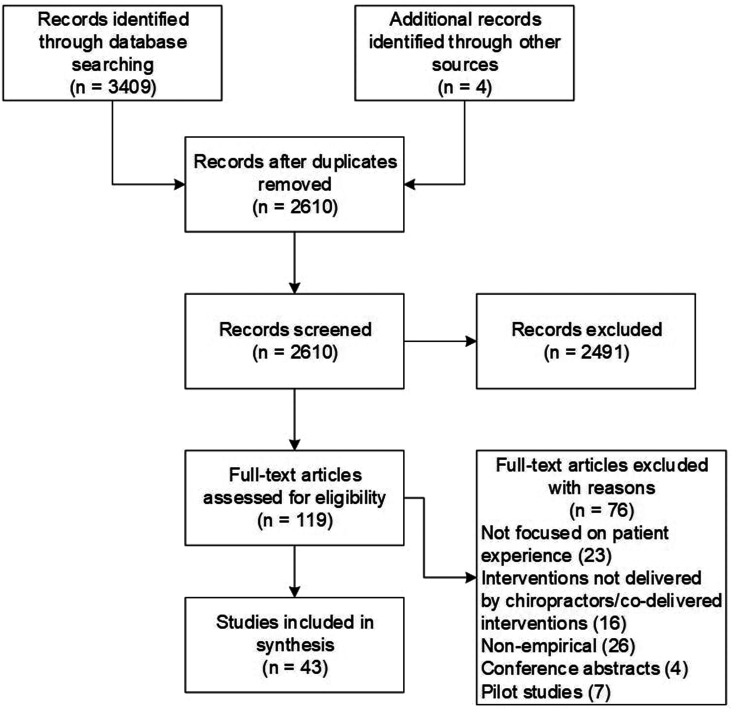

This systematic review has been written up in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. [10]

Literature Search

Table 1 An initial scoping search was conducted in 2020 to refine the research question and construct a full review protocol, published on PROSPERO, ID: CRD42020203251. Terms included derivatives of chiropractic and patient experience and satisfaction, an example search string can be seen in Table 1. The search was restricted to research published after 2005, following a systematic review published on patient satisfaction. [6] Several databases were searched yielding the following search results:

PubMED (506),

Cochrane (115),

Excerpta Medical Database and Allied and Alternative Medicine (EMBASE) (355),

CINAHL (517),

Index to Chiropractic Literature (ICL) (1758), and

Web of Science (158) by MH in 2021.A bibliography search was also conducted to check for relevant studies.

Article Selection

Articles that met the following criteria were eligible for inclusion in this review:(1) focused on patient satisfaction or patient experience within chiropractic care,

(2) primary empirical studies: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods, and

(3) published in English.Papers were excluded if they were:

(1) focus on perceptions of chiropractic care,

(2) co-delivered interventions, and

(3) case studies, pilot studies, conference abstracts, and non-empirical and secondary studies.

Figure 1 Titles and abstracts were examined by at least one reviewer, with full-texts examined by two reviewers (DN and MH). There was 100% agreement on the final inclusion between the two reviewers. The screening and selection of studies is documented in the PRISMA in Figure 1.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data extraction included citation, country, aims, participants, setting, study design, measures of patient satisfaction and experience, other outcome measures, analysis, intervention groups (where appropriate), and relevant results. Quality assessment was carried out using Markoulakis and Kirsh rubric, [11] with broadly defined score descriptions, allowing for assessment of the methodological implications of the paper despite heterogenous study designs. Narrative synthesis was used to collate and integrate the findings of the included studies with textual descriptions developed to combine results and analyze the relationships between the studies. [12, 13] Data extraction and synthesis was conducted by two reviewers (DN and MH), with 25% of articles checked.

Results

Study Characteristics and Overview

Table 2 Forty-three studies were eligible for inclusion (see Figure 1 and Table 2). The studies were conducted across the United Kingdom, Europe, North America, Australia, and South Africa. Chiropractic care was delivered in a variety of settings: private practice, university clinics, specialized clinics (military medical centers, therapeutic community facility). The studies included participants seeking chiropractic care for a variety of conditions (spinal pain, low back pain, neck pain, leg pain, headaches, and musculoskeletal conditions) and treatment of specialized populations (pediatric patients, pregnant mothers, older adults, military personnel, and athletes).

Generally, chiropractic patients are very satisfied with their care with high proportions generating consistently high satisfaction scores. [14, 15] This includes patient groups receiving care in both the independent and public sector. [16] Studies recruiting patients presenting with conditions commonly seen by chiropractors reported high to very high satisfaction/experience scores with care. [17–20] This is also true of parental satisfaction with pediatric care where scores range from around 75% to 95% satisfaction. [21–24]

Results of the quality assessment identified that reporting quality was mixed. However, no studies were marked as very poor or poor. The main methodological weaknesses identified were limited details on patient recruitment and the setting of chiropractic care. Within the quantitative studies, the main limitations were potential for respondent bias, and no details or limited details on generalizability. Taking into consideration the implications of these methodological flaws, no findings were deemed inappropriate and all concepts from the studies were included in the synthesis.

Comparison of Patient Satisfaction to Other Interventions

Table 3 Ten included studies were randomized-clinical trials (Table 3). Notwithstanding their heterogeneity, all compared chiropractic treatment or spinal manipulative therapy delivered by chiropractors to a comparator group, including exercise, medication, light massage, or a variety of sham interventions. Five trials used a combined intervention with manipulation as an addition to standard medical care [25, 26] and a further 2 explored adding spinal manipulation to a form of home exercise [27, 28] or home exercise and advice. [29]

For all trials, chiropractic care either alone or as adjunctive to other interventions generated significantly higher satisfaction scores than comparator interventions (see Table 3). Most comparators where chiropractic care performed better were either some form of home exercise, medication, or standard medical care. Where clinicians were involved in delivering substantive interventions such as forms of supervised exercise, chiropractic care either scored equal satisfaction or in one case less satisfaction (see Table 3). Furthermore, the addition of chiropractic care to an existing treatment generated better satisfaction than the existing treatment alone. [25, 26] This was also seen in audits of chiropractic care, where a package of manual care added to usual care generated significantly greater satisfaction than usual care plus medication. [30]

Three national surveys where chiropractors were compared to medical care were included. [31-33] Patients attending for chiropractic care were nearly twice as likely to be satisfied with the care received than those seen by medical doctors (odds ratio [OR]: 1.79 [1.35-2.39]) and 1.5 times as likely to be satisfied with the results of care (OR: 1.52 [1.15-2.02]). [31] Gaumer, Gemmen [32] reported that patients with prior experience of chiropractic care compared to none were less satisfied with other health care providers (87.3% satisfaction compared to 97.3% respectively). In a study of Medicare beneficiaries (n = 12?170) with a diagnosis of musculoskeletal disease visiting either private chiropractic care or medical care, those receiving chiropractic had higher satisfaction with follow-up after initial visit and with information provided about what was wrong with them. [33]

Haas, Sharma, Stano [34] followed a cohort of patients who chose chiropractic care compared to medical care. Patient satisfaction significantly favored chiropractic care with satisfaction scores of 86.4% for chronic patients and 90% among acute patients, whereas for medical doctors these scores were 71% and 76%, respectively. Furthermore, using a healthcare attitudes scale, trust in chiropractors was around 95% in those patients choosing chiropractic care whereas this figure was around 60% in those choosing medical care. Additionally, confidence in the provider of choice was 83% to 93% and 61% to 75% for those choosing chiropractors and medical doctors, respectively.

Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction With Chiropractic Care

An in-depth exploration of satisfaction and quality judgments by Canadian patients explored their experiences of visiting physicians and chiropractors. [35] Chiropractic care was judged predominantly on treatment outcomes where high satisfaction was associated with positive outcomes and low satisfaction with less positive outcomes. Chiropractors’ diversity of treatment options and the perceived ability to handle multiple problems simultaneously generated high satisfaction. Cost was not a factor for dissatisfaction in chiropractic care despite patients attending chiropractic care 5 times more often on average than seeing their physician.

As an alternative to satisfaction Ryan, Too, Bismark [36] looked at patient complaints comparing chiropractic, physiotherapy, and osteopathic settings in Australia. Chiropractors had significantly higher complaints than both osteopaths (3 times higher) and physiotherapists (6 times higher). Concerns around professional conduct accounted for half of all complaints with male practitioners, individuals over 65 years of age, and those practicing in metropolitan areas at higher risk of complaints. Among chiropractors only, around 1 in 100 practitioners were subject to more than one complaint. This accounted for 36% of all complaints within the profession suggesting that a small number of individuals significantly skew professional dissatisfaction from patients.

Factors Impacting Chiropractic Patient Satisfaction

Treatment outcomes and reactions were suggested to impact patient satisfaction scores. In qualitative interviews with patients receiving spinal manipulative therapy or exercises, common determinants of satisfaction were perceived treatment effect and changes in pain. [37] Similarly, negative treatment outcomes conversely influenced satisfaction. In a cohort study following patients’ outcomes of chiropractic care, patients had a mean score of 9.1 out of 10, but their satisfaction was negatively impacted if they perceived they had symptomatic reactions and were 19% more likely to report “poor” satisfaction (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.78-1.79). [38] These findings are similar with parental satisfaction with pediatric chiropractic care, [24] with moderate negative correlations between distress after care and parental satisfaction (?0.31) and moderate positive correlations between improvement scores and parental satisfaction (0.42).

From qualitative interviews embedded in a randomized controlled trial, content analysis was used to identify the common determinants of satisfaction. [37] Participants felt that the interaction with clinicians and their attributes were important, as well as information regarding exercises, tailored care, and information on the cause, prevention and prognosis of the condition. [37] In sport settings, where chiropractic care was delivered by students, satisfaction levels were statistically significantly linked to patients’ ratings of their assessment (P = .005), the communication of the student (P = .006), their views of student competence (P = .01) and conduct of the student (P = .036). [39]

In private chiropractic clinics in the United States, chronic low back pain and neck pain patients’ global ratings of their care were positively associated with the length of time they had been receiving chiropractic care prior to the study (r = 0.07; P = <.05), length of time seeing the chiropractor in the study (r = 0.09; P < .0001), number of visits to the chiropractor in the study (r = 0.05; P = <.05). [18] Previous experience of chiropractic care was associated with patient satisfaction levels in athletes receiving chiropractic care in sports settings. [39]

Included studies explored organizational issues with care most often waiting times, length of consultations, care delivery settings and costs. In a study by Brown, Bonello, Fernandez-Caamano, Eaton, Graham, Green [40] a large proportion either strongly agreed or agreed that they were satisfied with waiting times and the length of consultation times for chiropractors (92.9% and 94.6%, respectively). Similarly, patients’ expectations that their chiropractor would allow sufficient time for their consultation were substantively met with 97% indicated that this has happened [41] or that the consultation time was the right amount (84.5%). [42] MacPherson, Newbronner, Chamberlain, Hopton [41] also reported that in terms of the clinical setting, more than 90% of patients’ expectations and experiences corresponded.

Patient Experiences With Chiropractic Care

An observational study used the Consultation and Relational Empathy questionnaire within a chiropractic teaching clinic. [42] High proportions of patients (88%-97%) scored “very good” or “excellent” across all questions. In addition, 45.4% of participants achieved the maximum score. However, the authors suggest that the student patient encounter may skew scores, particularly in relation to the increased time students spend with patients.

Foley, Steel, Adams [43] explored the perceived experience of patients presenting with chronic conditions to complementary medicine setting including chiropractic care compared to medical care. Using the Perceived Provider Support Scale, higher scores were also found for chiropractors compared to medical doctors around issues including caring, acceptance, personal attention, talking openly, and trust.

Patient experiences are not universally positive. In a cross-sectional survey of chiropractic patients in the United Kingdom, despite chiropractic patients reporting a high level of satisfaction, patients’ expectations were least well met concerning information on the cost of the treatment at the first consultation. [41] There were also mismatched expectations concerning the chiropractor's contact with the patient's general practitioner and referral to other healthcare professionals, which did not happen as frequently as expected. [41]

In qualitative work, patients valued their interaction with their chiropractor: “Everyone was always courteous, kind, friendly…willing to answer any questions”. [44] Participants appreciated being listened to and valued the opportunity to express their concerns. This was noted as important for patients throughout the lifespan, from children seeking chiropractic care and feeling their condition was being taken seriously [45] to older adults receiving care. [46] Patients valued the professionalism of their practitioners, which they noted in the way chiropractors communicated with them. In general chiropractic practice [47] and following a randomized trial of chiropractic care [46] patients valued effective communication of their diagnosis and the treatment plan. This was also reflected in pregnant patients’ experiences of seeking chiropractic treatment, with participants noting their chiropractor explaining their condition, and involving the patient in developing a management plan. [48] Patients wanted help for their diagnosis and were appreciative of any individualized help advice including referrals to other healthcare professionals. [46]

Studies also explored the relationship between patients and their chiropractor. In patients receiving care for chiropractors in the Netherlands, patients completed the WAV-12 to measure working alliance between the chiropractor and the patient. [49] Their mean score was 49.14 (standard deviation [SD] 7.12) rated out of 60. The mean patient score, measured on a 1 to 5 Likert scale was 4.09 (SD ±0.59), with 5 representing an optimal alliance. [49] In a study comparing perceived support between chiropractic care and medical care, mean perceived support was higher for chiropractic care, this included components such as: practitioner caring about patient, practitioner accepting patient, trust for practitioner, talking openly with practitioner. [43] Trust was also examined in chiropractic teaching clinics, with 84.3% of participants reporting trusting their student chiropractor. Elements of the therapeutic relationship were also noted in qualitative literature, with participants noting that compassion, enthusiasm, genuineness, and helpfulness were important for their relationship. [46]

Discussion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of patient satisfaction with chiropractic care finding that patients reported high levels of satisfaction and positive experiences with their care. Patient experiences are more positive across several important domains including empathy, patient centredness, and perceived support when compared to medical doctors. Generally, where substantive clinician time or attention was involved, patients were more satisfied. Patients noted good communication, being listened to, the development of a strong therapeutic relationship and key traits such as trustworthiness and caring as being central in underpinning positive experience.

The findings of this work suggest the need for an explanation for high levels of satisfaction. For example, it is known that chronic pain patients can face long waits in seeking help without satisfaction from mainstream healthcare sources with minimal contact time with clinicians and poor experiences. [50] One explanation may be that compared with such negative experiences, attending care in a private setting where clinicians may have more time to communicate and spend time caring, higher satisfaction levels are reported. In this case, it is not clear, whether high satisfaction and good experiences are due to the chiropractic care itself or because of the relative experiences encountered in past health seeking activity. Furthermore, patient choice seems important in determining satisfaction levels and little is available outside of condition-based categorisation 3 within the literature that explores the underlying reasons for such choices in patients seeking and maintaining the use of chiropractic care.

Interestingly, satisfaction levels and positive patient experiences reported here were not associated with either technical or manipulative elements of the chiropractic encounter but often with perceptions of good communication, good relationships, trust, and care. Indeed a strong theme around the value of good communication was also found in a recent General Chiropractic Council survey of public perceptions of chiropractic care and chiropractors. [51] There is ample evidence to suggest that such contextual elements are centrally important in generating positive outcomes [52-54] and it is important for the profession to continue to develop a more complete understanding concerning the entirety of the therapeutic encounter, including patient practitioner relationships, as impactful in generating both clinical and experience related positive outcomes. For practitioners caring for patients, empathy, communication, and building trust are central to their patients’ positive experience along with a highly patient centered clinical paradigm. It is important that these skills and approaches are prioritized in therapeutic encounters.

Our study has several limitations. The study only focused on published manuscripts in English. There may be unpublished, or studies conducted and published in another language that have not been included which may have provided additional or contrasting findings. With some limited details on patient recruitment and variety of setting of chiropractic care, this has the potential for respondent bias and limited understanding on generalizability. However, given this review included studies in diverse settings and geographies, with a range of quantitative methodological designs and supportive qualitative work all pointing strongly in the same direction, it is unlikely that further studies concerning general satisfaction levels will change the overall positive conclusions. Further work should focus on factors that impact on patient satisfaction and how these can be improved to enhance patient experience, such as communication.

Conclusion

This systematic review suggests that high and consistent levels of both satisfaction and positive experiences are widely reported in the literature concerning patients undergoing chiropractic care. This was independent of study design, presenting conditions, age groups, and referral routes. Factors influencing satisfaction included clinical outcomes as well as the patients’ interaction with their chiropractor. Further research is required to explore the underlying reasons for the predominately positive experience including the influence of patient-practitioner relationships to generate positive experiences and clinical outcomes.

Authors’ Contributions:

MH ran the search. MH and DN completed article selection, data extraction, and synthesis. Both authors were involved in the write-up

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding:

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the General Chiropractic Council.

ORCID iD: Michelle M Holmes https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6018-2235

References:

Royal College of Chiropractors.

Chiropractic Competencies & Skills

Management of Low Back & Radicular Pain

Royal College of Chiropractors; 2015.Carey PF, Clum G, Dixon P.

Final Report of the Identity Consultation Task Force

Canada: World Federation of Chiropractic; April 30, 2005.- There are many more articles like this at our:

Beliveau PJH, Wong JJ, Sutton DA, et al.

The Chiropractic Profession: A Scoping Review of Utilization Rates,

Reasons for Seeking Care, Patient Profiles, and Care Provided

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Nov 22); 25: 35

ALL ABOUT CHIROPRACTIC SectionMasaracchio M, Kirker K, States R, Hanney WJ, Liu X, Kolber M.

Thoracic spine manipulation for the management of mechanical

neck pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0211877.- There are many more articles like this at our:

Rubinstein SM, de Zoete A, van Middelkoop M, Assendelft WJJ.

Benefits and Harms of Spinal Manipulative Therapy for the Treatment

of Chronic Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

of Randomised Controlled Trials

British Medical Journal 2019 (Mar 13); 364: 1689

ADVERSE EVENTS SectionGaumer G.

Factors Associated With Patient Satisfaction With Chiropractic Care:

Survey and Review of the Literature

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006 (Jul); 29 (6): 455–462Fitzpatrick RM.

Patient satisfaction.

In: Baum A. (ed.) Cambridge handbook of psychology, health and medicine.

Cambridge University Press; 1997; 301-304.Bergamino M, Vongher A, Mourad F, et al.

Patient concerns and beliefs related to audible popping sound and

the effectiveness of manipulation: findings from an online survey.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2022;45(2):144-152.Hurst L, Mahtani K, Pluddemann A, et al.

Defining Value-based Healthcare in the NHS

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Report; 2019.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al.

The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline

for reporting systematic reviews.

BMJ. 2021;372:n71.Markoulakis R, Kirsh B.

Difficulties for university students with mental health problems:

a critical interpretive synthesis.

Rev High Ed. 2013;37(1):77-100.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.

Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking

reviews in health care.

University of York; 2009.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al.

Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews.

Lancaster University; 2006.Damaske D, McCrossin P, Santoro F, Alcantara J.

The beliefs and attitudes of chiropractors and their patients

utilising an open practice environment.

Eur J Integr Med. 2016;8(4):438-445.Mace R, Cunliffe C, Hunnisett A.

Patient satisfaction and chiropractic style:

a cross sectional survey.

Clinical Chiropractic. 2012;15(2):92-93.

doi: 10.1016/j.clch.2012.10.041Field JR, Newell D.

Clinical outcomes in a large cohort of musculoskeletal patients undergoing

chiropractic care in the United Kingdom: a comparison of

self-and National Health Service–referred routes.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(1):54-62.Haneline MT.

Symptomatic outcomes and perceived satisfaction levels of chiropractic

patients with a primary diagnosis involving acute neck pain.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(4):288-96.- There are many more articles like this at our:

Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Spritzer KL, et al.

Experiences with Chiropractic Care for Patients With Low Back or Neck Pain

J Patient Exp 2020 (Jun); 7 (3): 357–364

LOW BACK PAIN Section- There are many more articles like this at our:

Moore C, Leaver A, Sibbritt D, Adams J.

The Features and Burden of Headaches Within a Chiropractic

Clinical Population: A Cross-sectional Analysis

Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2020 (Jan); 48: 102276

HEADACHE SectionNewell D, Diment E, Bolton JE.

An electronic patient-reported outcome measures system in UK chiropractic practices:

a feasibility study of routine collection of outcomes and costs.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(1):31-41.- There are many more articles like this at our:

Alcantara J, Nazarenko AL, Ohm J, Alcantara J.

The Use of the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information

System and the RAND VSQ9 to Measure the Quality of Life and

Visit-Specific Satisfaction of Pregnant Patients Under

Chiropractic Care Utilizing the Webster Technique

J Altern Complement Med. 2018 (Jan); 24 (1): 90–98

PATIENT SATISFACTION SectionAlcantara J, Ohm J, Alcantara J.

The use of PROMIS and the RAND VSQ9 in chiropractic patients

receiving care with the Webster technique.

Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;23:110-116.Miller JE, Hanson HA, Hiew M, Lo Tiap Kwong DS, Mok Z, Tee YH.

Maternal Report of Outcomes of Chiropractic Care for Infants

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Mar; 42 (3): 167–176- There are many more articles like this at our:

Navrud IM, Miller J, Eidsmo Bjørnli M, Hjelle Feier C, Haugse T.

A Survey of Parent Satisfaction with Chiropractic

Care of the Pediatric Patient

J Clin Chiropractic Pediatr. 2014;14(3):1167-1171

PEDIATRICS Section- There are many more articles like this at our:

Goertz CM, Long CR, Hondras MA, et al.

Adding Chiropractic Manipulative Therapy to Standard Medical

Care for Patients with Acute Low Back Pain: Results of a

Pragmatic Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 (Apr 15); 38 (8): 627–634

CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS Section- There are many more articles like this at our:

Goertz CM, Long CR, Vining RD, Pohlman KA, Walter J, Coulter I.

Effect of Usual Medical Care Plus Chiropractic Care vs Usual Medical

Care Alone on Pain and Disability Among US Service Members

With Low Back Pain

JAMA Network Open. 2018 (May 18); 1 (1): e180105

NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY Section- There are many more articles like this at our:

Maiers M, Bronfort G, Evans R, et al.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Exercise For Seniors

with Chronic Neck Pain

Spine J. 2014 (Sep 1); 14 (9): 1879–1889

CHRONIC NECK PAIN Section and the

EXERCISE AND CHIROPRACTIC SectionSchulz C, Evans R, Maiers M, Schulz K, Leininger B, Bronfort G.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Exercise for Older Adults

with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2019 (May 15); 27: 21Bronfort G, Hondras MA, Schulz CA, Evans RL, Long CR, Grimm R.

Spinal Manipulation and Home Exercise With Advice for Subacute

and Chronic Back-related Leg Pain: A Trial With Adaptive Allocation

Annals of Internal Medicine 2014 (Sep 16); 61 (6): 381—391Amorin-Woods LG, Parkin-Smith GF, Cascioli V, Kennedy D.

Manual care of residents with spinal pain within a therapeutic community.

Ther Communities. 2016;37(3):159-168.- There are many more articles like this at our:

Houweling TA, Braga AV, Hausheer T, Vogelsang M, Peterson C, Humphreys BK.

First-Contact Care With a Medical vs Chiropractic Provider After Consultation

With a Swiss Telemedicine Provider: Comparison of Outcomes,

Patient Satisfaction, and Health Care Costs in Spinal,

Hip, and Shoulder Pain Patients

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Sep); 38 (7): 477–483

INITIAL PROVIDER/FIRST CONTACT Section- There are many more articles like this at our:

Gaumer G, Gemmen E.

Chiropractic Use in the Medicare Population: Prevalence, Patterns, and

Associations With 1-Year Changes in Health and Satisfaction With Care

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014 (Oct); 37 (8): 542-551

MEDICARE SectionWeigel PA, Hockenberry JM, Wolinsky FD.

Chiropractic Use in the Medicare Population: Prevalence,

Patterns, and Associations With 1-Year Changes in Health

and Satisfaction With Care

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014 (Oct); 37 (8): 542-551- There are many more articles like this at our:

Haas M, Sharma R, Stano M.

Cost-effectiveness of Medical and Chiropractic Care

for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005 (Oct); 28 (8): 555–563

COST-EFFECTIVENESS SectionCrowther ER.

A comparison of quality and satisfaction experiences of patients

attending chiropractic and physician offices in Ontario.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014;58(1):24-38.Ryan AT, Too LS, Bismark MM.

Complaints about chiropractors, osteopaths, and physiotherapists:

a retrospective cohort study of health, performance, and conduct concerns.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2018;26:12.- There are many more articles like this at our:

Maiers M, Vihstadt C, Hanson L, Evans R.

Perceived Value of Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Exercise Among

Seniors With Chronic Neck Pain: A Mixed Methods Study

J Rehabil Med. 2014 (Nov); 46 (10): 1022–1028

EXERCISE AND CHIROPRACTIC SectionEriksen K, Rochester RP, Hurwitz EL.

Symptomatic Reactions, Clinical Outcomes and Patient Satisfaction

Associated with Upper Cervical Chiropractic Care:

A Prospective, Multicenter, Cohort Study

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011 (Oct 5); 12: 219Talmage G, Korporaal C, Brantingham JW.

An exploratory mixed-method study to determine factors that may affect

satisfaction levels of athletes receiving chiropractic care

in a nonclinical setting.

J Chiropr Med. 2009;8(2):62-71.Brown BT, Bonello R, Fernandez-Caamano R, Eaton S, Graham PL, Green H.

Consumer characteristics and perceptions of chiropractic and chiropractic

services in Australia: results from a cross-sectional survey.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(4):219-229.MacPherson H, Newbronner E, Chamberlain R, Hopton A.

Patients' Experiences and Expectations of Chiropractic Care:

A National Cross-sectional Survey

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2015 (Jan 16); 23 (1): 3Stomski N, Morrison P, Maben J, Amorin-Woods L, Ardakani E, Théroux J.

The adoption of person-centred care in chiropractic practice and

its effect on non-specific spinal pain: an observational study.

Complement Ther Med. 2019;44:56-60.Foley H, Steel A, Adams J.

Perceptions of person-centred care amongst individuals with chronic

conditions who consult complementary medicine practitioners.

Complement Ther Med. 2020;52:102518.Maiers M, Hondras MA, Salsbury SA, Bronfort G, Evans R.

What Do Patients Value About Spinal Manipulation and Home

Exercise for Back-related Leg Pain? A Qualitative Study

Within a Controlled Clinical Trial

Manual Therapy 2016 (Dec); 26: 183–191Hermansen MS, Miller PJ.

The lived experience of mothers of ADHD children

undergoing chiropractic care: a qualitative study.

Clin Chiropractic. 2008;11(4):182-192.Wells BM, Salsbury SA, Nightingale LM, Derby DC, Lawrence DJ, Goertz CM.

Improper communication makes for squat: a qualitative study of the

health-care processes experienced by older adults in a

clinical trial for back pain.

J Patient Exp. 2020;7(4):507-515.Myburgh C, Boyle E, Larsen JB, Christensen HW.

Health care encounters in Danish chiropractic practice from

a consumer perspectives—a mixed methods investigation.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2016;24:22.Sadr S, Pourkiani-Allah-Abad N, Stuber KJ.

The Treatment Experience of Patients with Low Back Pain During

Pregnancy and Their Chiropractors: A Qualitative Study

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2012 (Oct 9); 20 (1): 32Lambers NM, Bolton JE.

Perceptions of the quality of the therapeutic alliance in chiropractic

care in the Netherlands: a cross-sectional survey.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2016;24:18.Slade SC, Molloy E, Keating JL.

‘Listen to me, tell me’: a qualitative study of partnership

in care for people with non-specific chronic low back pain.

Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(3):270-280.General Chiropractic Council.

Public perceptions research: enhancing professionalism.

General Chiropractic Council; 2021.Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, Adams RD.

The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and patients

predicts outcome in chronic low back pain.

Phys Ther. 2013;93(4):470-478.Lakke SE, Meerman S.

Does working alliance have an influence on pain and physical functioning

in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain; a systematic review.

J Compass Health Care. 2016;3(1):1-10.Sherriff B, Clark C, Killingback C, Newell D.

Impact of contextual factors on patient outcomes following

conservative low back pain treatment: systematic review.

Chiropractic Manual Therap. 2022;30(1):1-29. doi: 10.1186/s12998-022-00430-8

Return to PATIENT SATISFACTION

Return to INITIAL PROVIDER/FIRST CONTACT

Since 1-03-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |