The Features and Burden of Headaches Within

a Chiropractic Clinical Population:

A Cross-sectional AnalysisThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2020 (Jan); 48: 102276 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Craig Moore, Andrew Leaver, David Sibbritt, Jon Adams

Faculty of Health,

University of Technology Sydney,

Level 8, Building 10, 235-253 Jones Street,

Ultimo, NSW, 2007, Australia.

Objectives: The aim of this study is to a) investigate the headache features and level of headache severity, chronicity, and disability found within a chiropractic patient population and b) to ascertain if patient satisfaction with headache management by chiropractors is associated with headache group or reason for consulting a chiropractor.

Design and setting: Consecutive adult patients with a chief complaint of headache participated in an online cross-sectional survey (n = 224). Recruitment was via a randomly selected sample of Australian chiropractors (n = 70). Headache features were assessed using International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria and level of headache disability measured using the Headache Impact Test instrument.

Results: One in four participants (n = 57; 25.4%) experienced chronic headaches and 42.0% (n = 88) experienced severe headache pain. In terms of headache features, 20.5% (n = 46) and 16.5% (n = 37) of participants had discrete features of migraine and tension-type headache, respectively, while 33.0% (n = 74) had features of more than one headache type. 'Severe' levels of headache impact were most often reported in those with features of mixed headache (n = 47; 65.3%) and migraine (n = 29; 61.7%). Patients who were satisfied or very satisfied with headache management by a chiropractor were those who were seeking help with headache-related stress or to be more in control of their headaches.

Conclusion: Many with headache who consult chiropractors have features of recurrent headaches and experience increased levels of headache disability. These findings may be important to other headache-related healthcare providers and policymakers in their endeavours to provide coordinated, safe and effective care for those with headaches.

Keywords: Chiropractic; HIT-6; Migraine; Practice-based research network; Tension-type headache.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Collectively, headache disorders, such as tension-type headache, migraine and cervicogenic headache, affect over half of all adults. [1–3] Headache disorders cause substantial personal suffering with adverse impacts on the family life, leisure time, social activities and work productivity of sufferers. [4–6] Migraine alone is the sixth leading cause of years lived with disability globally1 and the first cause of disability in those aged under fifty years. [8] While medical providers are the most common point of contact for those with headache, [8, 9] many with headache remain under-diagnosed or refrain from seeking medical help. [10–12]

The criteria utilised for headache classification are specified in the 3rd edition of International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3), [13] with headache classification primarily established via patient selfreport of their headache symptom profile. While the ‘gold standard’ for headache diagnosis is via face-to-face consultation with a neurologist, previous research suggests self-report instruments can be reliable for the screening of headache features within larger populations. [14–16] The epidemiology and burden of headaches found within primary care has previously been examined, with migraine identified as common within conventional care headache patient populations. [8, 17, 18] While much is known about the patient case-mix of those with headache under conventional care, many with headache also consult healthcare providers outside of medical settings. [19, 20] For example, general population studies have identified chiropractors as popular providers for headache management [21–23] and headache has been identified as one of the most common health complaints within chiropractic clinical populations. [24, 25] However, while evidence suggests manual therapies, as commonly utilised by chiropractors, may help in the prevention of tension-type headache and cervicogenic headache, [26, 27] the role of manual therapies for the prevention of migraine remains less certain, [28] despite many with migraine also seeking help from chiropractors. [21, 22]

The use of chiropractors for headache management is substantial [21, 29] and highlights the need for more information to understand the headache features within this clinical population. Such information may improve our understanding of the use and role of chiropractors within the field of headache management. As such, the aims of this study were to estimate the headache features and the level of headache severity, chronicity and disability found in those who present to chiropractors for headache management. In addition, this study aims to ascertain if headache type or the reasons for consulting a chiropractor were associated with patient satisfaction with headache management by a chiropractor.

Methods

The study collected data via an online cross-sectional survey from patients with headaches seeking help from Australian practicing chiropractors. This research was a sub-study of the Australian Chiropractic Research Network (ACORN), a national practice-based research network (PBRN) of Australian chiropractors. [30] Members of the ACORN network database are representative of the wider national population of Australian chiropractors regarding age and gender and generally representative for practice location (with over-representation of chiropractors in one state). [31] The research reported in this paper was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, University of Technology Sydney (Approval number: ETH182196).

Recruitment and participants

Invitational emails were limited to a random sample of 900 of the 1,680 practitioner members of the ACORN database (31st May to June 15th, 2018) due to the competing demands on the ACORN practitioners. Seventy chiropractors responded to the invitation agreeing to facilitate patient recruitment for the study. Patient recruitment occurred between the 11th July and 15th November 2018. Each participating chiropractor was posted study instructions along with 10 sealed envelopes (700 in total) for patient distribution. Each envelope contained a study background leaflet with a link to the online questionnaire. The survey introduction explained how consent to participate is assumed by starting the survey. Consecutive patients presenting on a regular consultation with a chief complaint of headache were informed of their eligibility to participate (avoiding recruitment of patients on an initial consultation). Inclusion criteria for the study were adult patients aged over 18 years, presenting with a primary complaint of headache with an adequate understanding of the English language in order to complete the questionnaire. At the close of the consultation, practitioners informed eligible patients of the study and that completing the questionnaire was voluntary and that all information provided was anonymous. Only headache patients who expressed an interest in participating in the study were provided with a sealed envelope and those who did participate completed the online questionnaire after leaving the practice. The researchers did not inform practitioners of patient involvement in the study to protect patient privacy and to avoid patient coercion by practitioners. Practitioners were not asked to collect additional information and no incentives were offered to study practitioners or patients.

Questionnaire

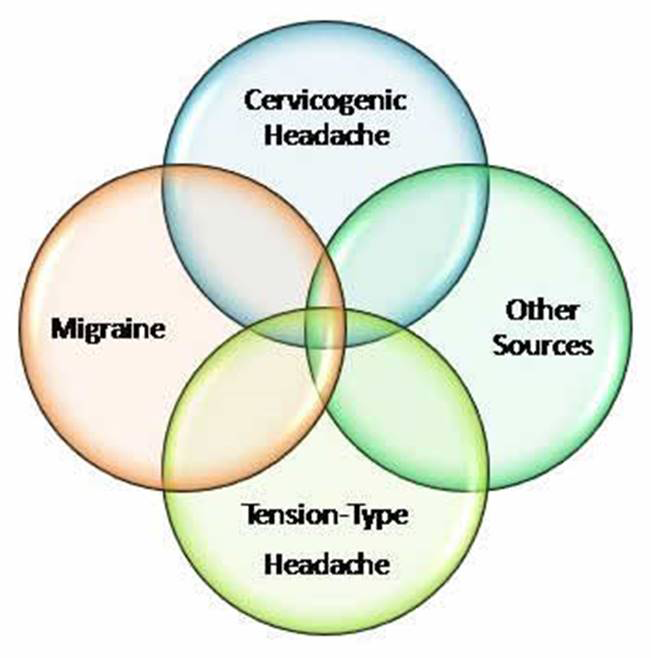

The 35–item study questionnaire included 4 main sections. The first section of the survey collected information on patient headache characteristics based on ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for migraine, tension-type headache and cervicogenic headaches [13] utilising survey questions similar to previous surveys. [16, 32] These headache disorders were selected due to having been previously reported as headache types more common to chiropractic headache patient populations. [22, 23, 29, 33] A standard numerical rating scale for pain (NPRS) was used to assess the level of headache pain intensity. [34]

The second section of the survey questioned participants regarding headache disability using the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) questionnaire. HIT-6 is reported to be a reliable and validated measure of headache disability. [35, 36] This instrument encompasses six questions across six representative categories commonly used to assess headache impact (pain, social functioning, role functioning, vitality, cognitive functioning, and psychological distress). [35] Summed values for the response to each question produces a total HIT-6 score for the level of patient headache disability using four score categories: Little or no impact (36–49); Moderate impact (50–55); Substantial impact (56–59); and Severe impact (60–78) to indicate the level of headache impact experienced in daily life. [37] The survey was pilot tested with 10 headache patients to assist decisions about survey duration, survey wording and item options.

The third questionnaire section explored the reasons patients seek help from chiropractors for their headache (“Please rank from the list below in order of importance the reasons why you seek help from the chiropractor for your headache”). Participants selected from options including: headache prevention, relief during a headache attack, help with headache related stress, feeling more in control of headache, reduce the effects of headaches on relationships and reduce the effects of headaches on ability to work. Participants were also questioned regarding their level of satisfaction with headache management by a chiropractor (“Please select which option best describes your level of satisfaction with chiropractic management of your headaches”). The last section of the survey collected information on patient socio-demographics and related characteristics.

Headache classification

Not all ICHD-3 criteria for cervicogenic headache can be collected via a survey format. For example, patients were not asked to include clinical and/or imaging evidence of a disorder or lesion within the cervical spine or soft tissues of the neck or to ascertain if abolition of their headache has been demonstrated following a diagnostic blockade of the cervical spine. Classification of cervicogenic headache was provided when subjects met the minimum ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria (as per Criterion C). Patients were considered to have chronic headache if they reported experiencing headaches on at least 15 days per month on average for 3 months [13] Participants who satisfied the criteria for more than one headache were classified as having ‘Mixed headache’. As with other studies, participants who did not meet the minimum ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria (for migraine, tension-type headache or cervicogenic headache) were categorised ‘Other headache’. [38–40]

A scoring algorithm was applied within Microsoft excel for migraine, tension-type headache and cervicogenic headache classification criteria with a conditional logic formula applied to identify patient responses that met ICHD-3 classification for each of these headache types. Two separate authors (CM and AL) reviewed the excel formulae results to assess for accuracy.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the study population are reported using descriptive statistics with categorical data presented using frequencies and percentages and continuous descriptive data are presented using means and standard deviations. Chi-square tests or Fishers exact test were used, as applicable, to examine the association between reasons for consulting a chiropractor and the level of satisfaction with headache management by a chiropractor and to see if headache type was associated with patient satisfaction with headache management by a chiropractor. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 25). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Study participants

Up to 700 eligible headache patients received an invitation to participate. Of those who participated in the study, 224 participants completed the section on headache characteristics and level of headache chronicity (i.e. minimum 32% response). Of these, 207 completed the section on their headache numerical pain score, 206 reported their level of satisfaction with headache management by a chiropractor, 205 reported their level of headache impact and 203 (29%) completed all sections of the survey including their sociodemographic details. Table 1 shows that 55 participants were male (27.1%) and 148 (72.9%) were female. The majority of participants were aged between 51–65 years (n = 65; 32.0%) and 41–50 years (n = 55; 27.1%). The largest ethnic group were Anglo-European (n = 185; 91.1%). Nearly a third of participants reported having a technical/private college level of education (n = 64; 31.5%) as their highest level of education. Salaried workers represented the largest employment group (n = 92; 45.3%) and the majority of participants were married or in a domestic partnership (n = 143; 70.4%). Three out of four participants (n = 159; 78.3%) reported having health insurance cover that included both hospital and extra insurance cover inclusive of chiropractic services.

Headache characteristics

Of those who completed the questionnaire section on headache characteristics (Table 2), 45% were classified as having features of a single headache type (n = 101) and 33% were classified as having features of more than one headache type (mixed headache) (n = 74) and 21.8% as having ‘Other headache’ (n = 49). Of those with features of a single headache, 20.5% had features of migraine (n = 46), 16.5% of tension-type headache (n = 37) and 8% of cervicogenic headache (n = 18). Of those with migraine, a similar proportion reported features of migraine with aura (n = 22; 9.8%) and without aura (n = 24; 10.7%). Fifty-seven participants (25.4%) reported a headache frequency consistent with chronic headaches. A total of 52 participants (25.1%) reported that their headache type had been previously diagnosed by a medical doctor. Of these, nearly two out of three (n = 32; 61.5%) reported a diagnosis of migraine was given by a medical doctor. In terms of level of headache pain intensity, 88 participants (42.5%) provided a numerical pain score of 8 or more out of 10 for their headache severity (where 0 = no pain and 10 = worse pain imaginable).

Headache impact

The level of headache impact (HIT-6) for each headache group, combining both episodic with chronic headaches, are presented in Table 3. The average overall level of headache impact (HIT-6) across all headache groups was 59.0 (SD 6.8). The headache type with the largest proportion with a score range of severe headache impact was for those with features of mixed headache (n = 47; 65.3%) and migraine (n = 29; 61.7%) In total, 149 participants with episodic and chronic headaches combined (72.7%) reported substantial or severe levels of headache impact.

For those experiencing less than 15 headache days per month (episodic headaches), the average overall level of headache impact (HIT-6) was in the ‘substantial’ impact range of 58.0 (SD 6.6). The largest proportion of those with episodic headaches with a score range of severe headache impact on their daily life was the mixed headache group (n = 31; 62.0%), followed by the migraine group (n = 18; 58.1%) (data not shown). For those experiencing more than 15 headache days per month (chronic headaches), the average overall level of headache impact was in the ‘severe’ impact range of 62.1 (SD 6.3). The largest proportion of those with chronic headaches with a score range of severe headache impact on their daily life was the cervicogenic headache group (n = 4; 80.0%). This was followed by those with mixed headache (n = 16; 72.7%) and migraine (n = 11; 68.7%) (data not shown).

Reasons and satisfaction with headache management

Table 4 shows the reasons why participants consulted a chiropractor for the management of headaches. Participants reported headache prevention (n = 190; 92.2%), followed by seeking relief during a headache attack (n = 166; 80.6%) and reducing the effects of headaches on ability to work (n = 166; 80.6%) as the highest-ranking reasons for consulting a chiropractor for help with headaches.

The majority of participants (90.3%) reported they were either satisfied or very satisfied with the chiropractic management of their headaches (n = 186). Table 5 shows the distribution of levels of satisfaction across the reasons for consulting a chiropractor. Those patients who were satisfied or very satisfied with headache management by a chiropractor were more likely to consider consulting a chiropractor to ‘help with headache related stress’ (p = 0.019) or to be ‘more control of their headaches’ (p = 0.032) as being important, compared to those who were neutral or unsatisfied.

The distribution of levels of satisfaction with headache management by a chiropractor based on patient headache group are presented in Table 6. It can be seen that there was no statistically significant association between headache type and patient satisfaction.

Discussion

Our study found a substantial proportion of those seeking help from chiropractors for headache management had features of recurrent primary headaches and high levels of headache severity, chronicity and disability. These patients were more often female, were aged between [41–65] and more often had a high level of socioeconomic status.

Our study found a similar proportion of participants had discrete features of either migraine or tension-type headache. However, while there is emerging good quality clinical evidence for manual therapies for the prevention of tension-type headache, [26, 41] level 1 evidence for manual therapies for the prevention of migraine remains limited and preliminary. [28, 42] It may, therefore, be that the use of chiropractors by those with migraine could also relate to other aspects of chiropractic headache management beyond the role of manual therapies alone. For example, previous research has identified that chiropractors utilise a multimodal approach when managing those with migraine that incorporates stress management, patient education and advice on lifestyle factors. [43] While this study found increased patient satisfaction with chiropractic headache management was associated with those motivated by the need to gain ‘more control of their headaches’, more research is needed to better understand the extent to which particular aspects of chiropractic patient care contribute to patient satisfaction with chiropractic headache management.

Our study found a substantial proportion of those with headache seeking help from chiropractors had features of mixed headaches, a finding that is likely explained by the high co-occurrence of migraine with tension-type headache. [22, 44] In addition, our study found a substantial proportion of those with headache seeking help from chiropractors scored their headache pain at the level of severe, and one in four reported a headache frequency consistent with a classification of chronic headache. Those with mixed, severe and chronic headaches are more likely to experience greater headache burden45–48 and are more likely to seek professional help, including from healthcare providers outside of medical settings. [49–51] More research is therefore needed to understand how chiropractors might assist those with increased headache burden. For example, clinical research evidence for the role of manual therapies for chronic headaches remains limited. [41, 42] In addition, many with chronic and disabling headaches commonly experience psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression. [52, 53] While this study found those seeking ‘help with headache-related stress’ were more likely to be satisfied with chiropractic headache management, there is little detailed knowledge regarding how chiropractors seek to assist those with psychiatric disabilities commonly associated with increased headache burden. Other healthcare providers should therefore remain aware of the use of chiropractors for headache and seek to understand patient views and experiences regarding the use and role of this provider for aspects of headache management.

In addition, our study found one in five participants were identified as having headache features that failed to fulfil the minimum criteria needed to assign a headache classification of either migraine, tensiontype headache or cervicogenic headache. While uncertainty remains about the significance of this finding, the true proportion of those with headache who meet all of the required ICHD criteria needed for a distinct headache classification remains unclear [44, 54] and overlapping headache characteristics are reported as common amongst those with recurrent headaches. [55, 56] Overlapping headache features may also help to explain why our study found there was no statistically significant association between headache grouping and patient satisfaction with chiropractic management. However, while those failing to fulfil the minimum criteria needed to assign a headache classification may partly be explained by the challenges of classifying headaches into discrete categories, it may also be a limitation of the self-report instrument utilised for the study.

Our study identified that many with headache seeking help from chiropractors experience increased levels of headache impact. Study participants with the highest level of headache impact were those with features of migraine and mixed headaches, a finding similarly identified in other studies. [4, 57] High levels of headache burden can adversely impact patient quality of life, including their work, leisure and social activities, 4 with migraine the largest cause of headache-related healthcare visits. [58] In this regard, it was not surprising that many respondents were motivated to seek help from chiropractors in order to reduce the impact of headaches on their work-life and relationships. The increased levels of headache impact amongst those seeking help from chiropractors, as identified by the findings of this study, highlights the need for chiropractors to monitor and evaluate the level of headache burden in those who are seeking their help. In doing so, it is incumbent upon chiropractors to utilise disease-specific measures to understand the impact of headaches on patient quality of life [59] and to carefully consider the healthcare needs of those who experience increased headache burden and the role of other healthcare providers in assisting in these circumstances. [60, 61] Since headache burden is also greater as treatment failure increases, [62] it is also vital for chiropractors to evaluate the research literature and to assist headache patients in understanding the quality of the evidence for headache treatments found both inside and outside chiropractic clinical settings.

Our study found nearly three out of every four patients who consult chiropractors with headache were female. A higher proportion of female patients with headache has been reported in those seeking help from Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) [63] and medical providers. [64] This finding is likely influenced by the higher percentage of women who experience migraine and tension-type headache, the most common recurrent headaches. [44, 65, 66] Nearly two thirds of our sample were aged between 41–65 years, despite evidence that the peak age of migraine decreases after menopause. [67] Since the peak age of those with tension-type headache in adult populations (over 18 years) is reported to be between 30–39 years68 and between 18–45 years for those with migraine (females), [57] it may be that headache patients seeking help from chiropractors do so later than the age of peak adult incidence and potentially later than seeking help from other primary care providers. Our study found the majority of chiropractic headache patients were well educated with nearly half having a university education, with two thirds being salary-workers or self-employed and three quarters reporting health insurance cover inclusive of chiropractic health services. With low employment status and lack of health insurance reported as economic barriers to medical headache treatment, [69] our findings may also suggest similar socioeconomic barriers may exist regarding patient access to non-medical headache providers such as chiropractors.

Our study has several limitations. The section of the questionnaire using self-report for headache features is unvalidated and this can increase the risk of an incorrect headache classification and the generalisability of the study findings. When considering this concern, we avoided participant grouping into ‘probable’ headache classification categories, as identified by ICHD, where increased overlap of headache features would increase the risk of misclassification. As such, study participants were only grouped under discrete headache categories when responses met all of the formal ICHD headache classification criteria. While favourable reliability of self-report headache instruments has been previously documented, [14, 70] future studies are needed to explore the validity of a self-report survey instruments for headache classification against that of face-to-face consultation. The low patient response rate and limited patient sample size may also result in headache groups and headache disability being under or over-represented.

Patient treatment satisfaction may also be influenced by the number of headache treatment visits individual respondents received. As such, our findings call for larger population studies to be conducted before robust conclusions can be made about the external validity of the findings. In addition, there is a need for future research to additionally assess the proportion of those seeking help from chiropractors who also have medication-overuse headache, known to be most common in those with chronic migraine. [71, 72]

Conclusion

Our study found a high proportion of patients who consult chiropractors for headache management experience features of common recurrent headaches. In addition, many of these patients experience high levels of headache pain, chronicity and headache-related disability. However, these findings highlight the need for larger population studies before robust conclusions can be made about the headache profile of this patient population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the chiropractors who participated in the study and the Australian Chiropractors’ Association for their financial support for the ACORN PBRN.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

CM, JA, AL and DS designed the study. CM carried out the data collection and CM and DS provided the analysis and interpretation. CM wrote the drafts with revisions made by JA, AL and DS. All authors contributed to the intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Craig Moore: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Andrew Leaver: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing, Formal analysis.

David Sibbritt: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis.

Jon Adams: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare no competing interests related to the contents of this manuscript and that they have received no direct or indirect payment in preparation of this manuscript.

References:

Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, et al.

Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years

Lived with Disability for 301 Acute and Chronic Diseases and

Injuries in 188 Countries, 1990-2013: A Systematic Analysis

for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013

Lancet. 2015 (Aug 22); 386 (9995): 743–800Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al.

The global burden of headache:

A documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide.

Cephalalgia. 2007;27:193–210Sjaastad O, Bakketeig LS.

Prevalence of cervicogenic headache: Vågå study of headache epidemiology.

Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;117:173–180Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z, et al.

The impact of headache in Europe: Principal results of the Eurolight project.

J Headache Pain. 2014;15:1–15HAv Suijlekom, Lamé I, Stomp-van den Berg SGM, Kessels AGH, Weber WEJ.

Quality of life of patients with cervicogenic headache: A comparison

with control subjects and patients with migraine or tension-type headache.

Headache. 2003;43:1034–1041.Vosoughi K, Stovner LJ, Steiner TJ, et al.

The burden of headache disorders in the Eastern Mediterranean Region,

1990-2016: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study 2016.

J Headache Pain. 2019;20:40.Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Vos T, Jensen R, Katsarava Z.

Migraine is first cause of disability in under 50s:

will health politicians now take notice?

J Headache Pain. 2018;19:1–4Ridsdale L, Clark LV, Dowson AJ, et al.

How do patients referred to neurologists for headache differ

from those managed in primary care?

Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:388–395.Latinovic R, Gulliford M, Ridsdale L.

Headache and migraine in primary care: Consultation, prescription,

and referral rates in a large population.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:385–387.Kernick D, Stapley S, Hamilton W.

GPs’ classification of headache: is primary headache underdiagnosed?

Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:102–104Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al.

Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy.

Lancet Neurol. 2007;68:343–349Katsarava Z, Mania M, Lampl C, Herberhold J, Steiner TJ.

Poor medical care for people with migraine in Europe –

Evidence from the Eurolight study.

J Headache Pain. 2018;19(10)Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society.

The international classification of headache disorders (3rd edition).

Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211.Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, et al.

A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care:

The ID Migraine™ validation study.

Neurology. 2003;61:375–382.Hagen K, Zwart JA, Vatten L, Stovner LJ, Bovim G.

Head-HUNT: validity and reliability of a headache questionnaire

in a large population-based study in Norway.

Cephalalgia. 2000;20:244–250.Steiner TJ, Gururaj G, Andree C, et al.

Diagnosis, prevalence estimation and burden measurement in population

surveys of headache: Presenting the HARDSHIP questionnaire.

J Headache Pain. 2014;15(3)Coeytaux RR, Linville JC.

Chronic daily headache in a primary care population:

Prevalence and headache impact test scores.

Headache. 2007;47:7–12.Hjalte F, Olofsson S, Persson U, Linde M.

Burden and costs of migraine in a Swedish defined patient population–

a questionnaire-based study.

J Headache Pain. 2019;20:65.Wells RE, Bertisch SM, Buettner C, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP.

Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults

with migraines/severe headaches.

Headache. 2011;51:1087–1097.Al-Hashel JY, Ahmed SF, Alshawaf FJ, Alroughani R.

Use of traditional medicine for primary headache disorders in Kuwait.

J Headache Pain. 2018;19:118.Sanderson JC, Devine EB, Lipton RB, et al.

Headache-related health resource utilisation in chronic

and episodic migraine across six countries.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:1309–1317.Kristoffersen ES, Grande RB, Aaseth K, Lundqvist C, Russell MB.

Management of primary chronic headache in the general population:

The Akershus study of chronic headache.

J Headache Pain. 2012;13:113–120Moore CS, Sibbritt DW, Adams J.

A critical review of manual therapy use for headache disorders: Prevalence,

profiles, motivations, communication and self-reported effectiveness.

BMC Neurol. 2017;17:1–11Brown BT, Bonello R, Fernandez-Caamano R, et al.

Consumer characteristics and perceptions of chiropractic and chiropractic

services in australia: Results from a cross-sectional survey.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37:219–229.Hartvigsen J, Bolding-Jensen O, Hviid H, Grunnet-Nilsson N.

Danish chiropractic patients then and now—A comparison between 1962 and 1999.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26:65–69.Mesa-Jiménez JA, Lozano-López C, Angulo-Díaz-Parreño S, et al.

Multimodal manual therapy vs. Pharmacological care for management of

tension type headache: A metaanalysis of randomized trials.

Cephalalgia. 2015;35:1323–1332Chaibi A, Russell MB.

Manual Therapies for Cervicogenic Headache: A Systematic Review

J Headache Pain. 2012 (Jul); 13 (5): 351–359Rist PM, Hernandez A, Bernstein C, et al.

The Impact of Spinal Manipulation on Migraine Pain and Disability:

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2019 (Apr); 59 (4): 532–542Adams J, Barbery G, Lui C-W.

Complementary and alternative medicine use for headache and migraine:

A critical review of the literature.

Headache. 2013;53:459–473.Adams J, Steel A, Moore C, Amorin-Woods L, Sibbritt D.

Establishing the ACORN national practitioner database: Strategies to

recruit practitioners to a national practice-based research network.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39:594–602.Adams J, Peng W, Steel A, et al.

A cross-sectional examination of the profile of chiropractors recruited to

the Australian Chiropractic Research Network (ACORN):

A sustainable resource for future chiropractic research.

BMJ Open. 2017;7:1–8.Andree C, Vaillant M, Barre J, et al.

Development and validation of the Eurolight questionnaire to

evaluate the burden of primary headache disorders in Europe.

Cephalalgia. 2010;30:1082–1100Kristoffersen ES, Lundqvist C, Aaseth K, Grande RB, Russell MB.

Management of secondary chronic headache in the general population:

The Akershus study of chronic headache.

J Headache Pain. 2013;14:1–8Bonstra AM, Stewart RE, Köke AJA, et al.

Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the numeric rating scale

for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain:

Variability and influence of sex and catastrophizing.

Front Psychol. 2016;7:1466.Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, et al.

A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: The HIT-6™.

Qual Life Res. 2003;12:963–974Yang M, Rendas-Baum R, Varon SF, Kosinski M.

Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6™) across episodic and chronic migraine.

Cephalalgia. 2011;31:357–367Ware JE, Bjorner JB, Kosinski M.

Practical implications of item response theory and computerized adaptive testing:

A brief summary of ongoing studies of widely used headache impact scales.

Med Care. 2000;38:II73–II82.Minen MT, Loder E, Friedman B.

Factors associated with emergency department visits for migraine:

An observational study.

Headache. 2014;54:1611–1618Kristoffersen ES, Lundqvist C, Russell MB.

Illness perception in people with primary and secondary

chronic headache in the general population.

J Psychosom Res. 2019;116:83–92.Peng K-P, Wang S-J.

Epidemiology of headache disorders in the Asia-Pacific region.

Headache. 2014;54:610–618A. Chaibi, M.B. Russell

Manual Therapies for Primary Chronic Headaches:

A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

J Headache Pain. 2014 (Oct 2); 15: 67Cerritelli F, Ginevri L, Messi G, et al.

Clinical effectiveness of osteopathic treatment in chronic migraine:

3-Armed randomized controlled trial.

Complement Ther Med. 2015;23:149–156Moore C, Leaver A, Sibbritt D, Adams J.

The Management of Common Recurrent Headaches by Chiropractors:

A Descriptive Analysis of a Nationally Representative Survey

BMC Neurology 2018 (Oct 17); 18 (1): 171Lyngberg AC, Rasmussen BK, Jørgensen T, Jensen R.

Has the prevalence of migraine and tension-type headache changed

over a 12-year period? A Danish population survey.

Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:243–249Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al.

Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs:

Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS).

Cephalalgia. 2011;31:301–315Fuensalida-Novo S, Palacios-Ceña M, Fernández-Muñoz JJ, et al.

The burden of headache is associated to pain interference, depression

and headache duration in chronic tension type headache:

A 1-year longitudinal study.

J Headache Pain. 2017;18(119)Buse D, Manack A, Serrano D, et al.

Headache impact of chronic and episodic migraine: results from the

American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study.

Headache. 2012;52:3–17.Vo P, Fang J, Bilitou A, Laflamme AK, Gupta S.

Patients’ perspective on the burden of migraine in Europe:

A cross-sectionala analysis of survey data in France,

Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

J Headache Pain. 2018;19:82Zhang Y, Dennis JA, Leach MJ, et al.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among US Adults With

Headache or Migraine: Results from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey.

Headache. 2017;57:1228–1242Lee J, Bhowmick A, Wachholtz A.

Does complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use reduce negative life

impact of headaches for chronic migraineurs? A national survey.

SpringerPlus. 2016;5:1–10.Silberstein SD, Lee L, Gandhi K, et al.

Health care resource utilization and migraine disability

along the migraine continuum among patients treated for migraine.

Headache. 2018;58:1579–1592Buse D, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton R.

Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine

and episodic migraine sufferers.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:428–432Holroyd KA, Stensland M, Lipchik GL, et al.

Psychosocial correlates and impact of chronic tension-type headaches.

Headache. 2000;40:3–16.Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Olesen J.

A population-based analysis of the diagnostic criteria of the International Headache Society.

Cephalalgia. 1991;11:129–134.Vincent MB.

Cervicogenic headache: A review comparison with migraine,

tensiontype headache, and whiplash.

Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:238–243Turkdogan D, Cagirici S, Soylemez D, et al.

Characteristic and overlapping features of migraine and tension-type headache.

Headache. 2006;46:461–468Smitherman TA, Burch R, Sheikh H, Loder E.

The prevalence, impact, and treatment of migraine and severe headaches

in the United States: A review of statistics from national surveillance studies.

Headache. 2013;53:427–436Korolainen MA, Kurki S, Lassenius MI, et al.

Burden of migraine in Finland: Health care resource use,

sick-leaves and comorbidities in occupational health care.

J Headache Pain. 2019;20:1–11.Leonardi M, Raggi A.

A narrative review on the burden of migraine:

When the burden is the impact on people’s life.

J Headache Pain. 2019;20:41.Zeeberg P, Olesen J, Jensen R.

Efficacy of multidisciplinary treatment in a tertiary referral headache centre.

Cephalalgia. 2005;25:1159–1167Sahai-Srivastava S, Sigman E, Uyeshiro Simon A, Cleary L, Ginoza L.

Multidisciplinary Team Treatment Approaches to Chronic Daily Headaches.

Headache. 2017;57:1482–1491Martelletti P, Schwedt TJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al.

My Migraine Voice survey: A global study of disease burden among individuals

with migraine for whom preventive treatments have failed.

J Headache Pain. 2018;19:115.Rhee TG, Harris IM.

Gender differences in the use of complementary and alternative medicine

and their association with moderate mental distress in US adults with migraines/severe headaches.

Headache. 2017;57:97–108Hunt K, Adamson J, Hewitt C, Nazareth I.

Do women consult more than men? A review of gender and consultation

for back pain and headache.

J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16:108–117Finocchi C, Strada L.

Sex-related differences in migraine.

Neurol Sci. 2014;35(Suppl 1):207–213.Khil L, Pfaffenrath V, Straube A, Evers S, Berger K.

Incidence of migraine and tensiontype headache in three different populations

at risk within the German DMKG headache study.

Cephalalgia. 2012;32:328–336.Mattsson P.

Hormonal factors in migraine: A population-based study of women aged 40 to 74 years.

Headache. 2003;43:27–35Schwartz BS, Stewart WF, Simon D, Lipton RB.

Epidemiology of tension-type headache.

JAMA. 1998;279:381–38Lipton RB, Serrano D, Holland S, et al.

Barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of migraine:

Effects of sex, income, and headache features.

Headache. 2013;53:81–92.Lipton RB, Serrano D, Buse DC, et al.

Improving the detection of chronic migraine: Development and validation

of Identify Chronic Migraine (ID-CM).

Cephalalgia. 2015;36:203–215Stovner LJ, Andree C.

Prevalence of headache in Europe: A review for the Eurolight project.

J Headache Pain. 2010;11:289–299Westergaard ML, Glümer C, Hansen EH, Jensen RH.

Prevalence of chronic headache with and without medication overuse:

Associations with socioeconomic position and physical and mental health status.

PAIN®. 2014;155:2005–2013

Return to HEADACHE

Return to COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to INITIAL PROVIDER/FIRST CONTACT

Since 8-23-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |