What Have We Learned About the Evidence-informed

Management of Chronic Low Back Pain?This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Spine J. 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 266–277 ~ FULL TEXT

Scott Haldeman, DC, MD, PhD, FRCP(C), Simon Dagenais, DC, PhD

Department of Neurology,

University of California,

Irvine, CA, USA

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

This special focus issue has presented information on 24 categories of treatments that are widely prescribed for the management of chronic low back pain (CLBP) without surgery, and also provided an overview of commonly available surgical options. The authors of each of these papers have spent a great deal of time and effort discussing these treatment approaches and providing their interpretation of the evidence that is available to justify their use. The fact that there are 25 categories of treatment presented in this special focus issue, each of which has multiple subcategories, is a testament to the fact that no single approach has yet been able to demonstrate its definitive superiority. This situation makes it very challenging for clinicians, policy makers, insurers, and patients to make decisions regarding which treatment is the most appropriate for CLBP.

Although readers may be tempted to examine only those articles describing their favorite (or least favorite) treatments to find evidence that simply affirms their beliefs, it is highly recommended that the entire special focus issue be perused to compare and contrast the theories and evidence supporting all approaches. This can help overcome our natural tendencies to support only those treatments with which we are most familiar and dismiss those about which we know little. Only when reasonably informed about all available treatments will purchasers (eg, patients, insurers) and providers of care truly understand the current state of the science and art and be in a position to compare and make decisions concerning the treatment options for CLBP. This article will attempt to facilitate this task by summarizing some of the pertinent information from each of the articles presented in this special focus issue,

Articles from expert clinicians

Readers should be aware of possible biases inherent to the type of review articles contained in this special focus issue, many of which were contributed by authors known to have an interest in specific interventions. These authors are naturally more likely to be optimistic about the benefits of a procedure than others who are offering a different treatment approach. Presumably, clinicians who contributed articles on specific interventions used in their practice would not be offering them to their patients if they were not enthusiastic about their superiority over other options. This enthusiasm is seen most commonly in articles with extensive discussions about the theoretical basis of a treatment approach for which there is little available evidence of efficacy. Similarly, this zest may be at play when authors attempt to minimize or criticize the importance of clinical trials that reported negative outcomes they feel are not reflective of what is observed in their daily practice.

Articles by clinical researchers

A number of these review articles were written by authors who work primarily as researchers and are not involved in clinical practice offering the treatments about which they wrote. These authors may exhibit other biases to their interpretation of the scientific literature supporting or refuting the efficacy of a treatment approach. Whereas clinicians tend to be overly optimistic about the efficacy of an intervention based mainly on their personal experience, researchers (many of whom are clinical epidemiologists) tend to be overly pessimistic about interventions for which there is little, low-quality, or conflicting evidence of efficacy. This is based, in part, on medicine’s long history of once promising but eventually discredited treatments, and the principle of primum non nocere. Although the former often discount research evidence, the latter often overlook clinical experience; neither viewpoint is ideal.

Systematic Reviews

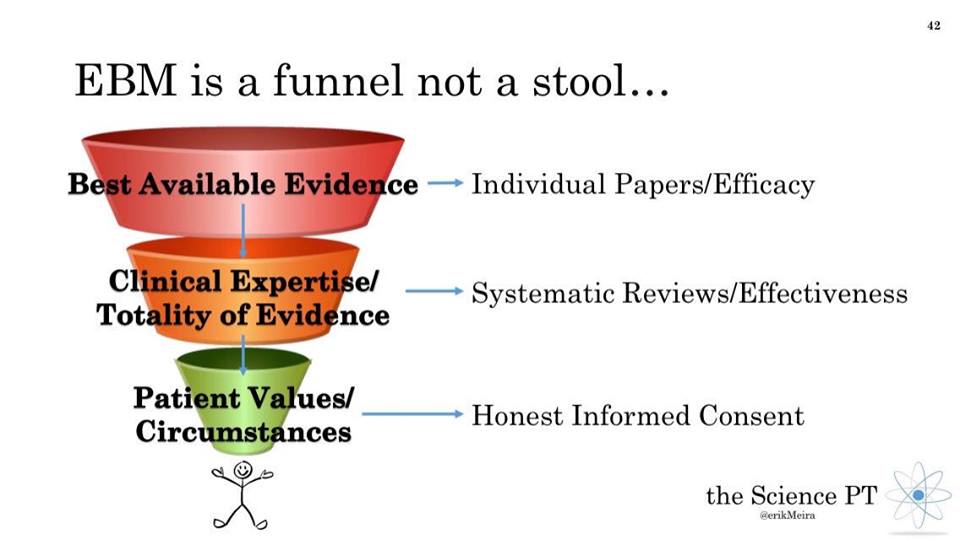

Systematic reviews (SRs) conducted on intervention for CLBP that adhered strictly to the principles and rigorous methodology of evidence-based medicine (EBM) often conclude with the statement that there is insufficient evidence and more research is necessary. Although the efforts of EBM to improve the practice of health care are laudable, decisions must still be made on a daily basis in the absence of the amount and quality of evidence necessary to convince clinical epidemiologists that an intervention is beneficial. Another important reality that must be considered by readers is that funding and conducting multiple high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for each of the 200 or more individual treatment options currently available for CLBP is simply beyond the realm of possibility. Those reviewing this special focus issue must therefore decide whether they wish to rely on the enthusiasm of clinicians practicing a particular treatment approach or on the skepticism of clinical epidemiologists who rely on the evidence. A blend of both views, where possible, is perhaps the most useful current approach.

Evidence informed versus evidence based

Ideally, there would be multiple high-quality RCTs supporting each of the interventions discussed in this special focus issue to provide a solid EBM approach to CLBP. In reality, SR methodology confined to high-quality RCTs would likely find only limited evidence for many of these interventions. Given the wealth of clinical experience among invited authors, it was intended that articles in this special focus issue present evidence-informed rather than strictly evidence-based recommendations. The guiding principle behind evidence-informed management is that authors should be aware of and use research evidence when available, make personal recommendations based on clinical experience when it is not available, and be transparent about the process used to reach their conclusion. The instructions to authors made it clear that articles should not be narrative reviews founded solely on their opinions and clinical experience. Authors were asked to systematically search the biomedical literature to uncover, evaluate, and summarize recent evidence using some of the methodology recommended by the Cochrane Back Review group. [1] They were also given the liberty to make personal recommendations on specific aspects of a treatment in the absence of other available evidence.

All authors were asked to include a description of terminology surrounding that intervention, a detailed description of the intervention so that patients considering a particular intervention may know what to expect, a summary of important historical events, the qualifications required to administer that intervention, general information on costs and reimbursement policies in the United States, the theories supporting its mechanism of action, the most appropriate indications and contraindications, the ideal CLBP patient for that intervention, review methods used to uncover evidence of efficacy, appraisal and summary of available evidence by study design (clinical guidelines, SRs, RCTs, observational studies [OBSs]), and discussion of known or potential harms. Although the approach taken by each group of authors differed somewhat, most followed this format admirably and genuinely attempted to provide evidence-informed recommendations to assist stakeholders evaluating these various interventions for CLBP.

Pretreatment diagnostic testing

Table 1

page 3Table 1 summarizes recommendations by the authors regarding the diagnostic testing procedures that are required or recommended before considering each treatment approach. It should be evident to anyone reading this special focus issue that the diagnostic testing recommended before providing a treatment is, with few exceptions, almost identical. Every article in this special focus issue recommends or infers that it is important to conduct a thorough history and physical examination to rule out the possibility of serious pathology or ‘‘red flags’’ indicating organic conditions requiring immediate attention before considering any treatment for CLBP. Certain of these articles list some of the red flags whereas others use a more general term. None of the articles suggest that the treatment approach should be considered in patients with these red flags.

It is interesting to note that, despite the enormous resources devoted to daily use of diagnostic testing for CLBP, few authors reported that such testing was required before considering a particular intervention. Those who did suggest the use of specific diagnostic testing generally did not support these recommendations with citations to any studies demonstrating a change in outcomes for patients who did and did not undergo advanced diagnostic testing before receiving an intervention. This observation brings into question the routine use of laboratory testing, X-rays, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), discography, nerve conduction velocity, and electromyography by clinicians evaluating CLBP.

In their review of surgical options for CLBP, Don and Carragee discuss the failure of advanced imaging such as CT or MRI to delineate a clear pathoanatomic cause for a patient’s symptoms. In their discussion of epidural steroid injections, De Palma and Slipman note that the use of discographydwhich is often touted as superior to CT or MRIdis controversial and has not been critically evaluated for CLBP. This is echoed by Don and Carragee, who report that the discography is not validated, is painful in 30% to 80% of asymptomatic subjects, and, even in a best-case scenario, has a positive predictive value of only 50% to 60% for resolution of low back pain (LBP) after surgical removal of the suspected pain generator identified by discography.

A number of articles suggested that an initial trial of treatment may be used to help customize an intervention according to patient response. This was mainly noted in articles on manual therapies including spinal manipulation, mobilization, and massage, as well as trigger point injections, which also rely on manual palpation to identify areas to be injected. Although the logic behind diagnosis by treatment appears reasonable for these types of safe and noninvasive therapies, there were no citations provided to support these statements.

The only two treatment approaches for which authors cited evidence that the success of an intervention is dependent on examination findings were McKenzie methodd which bases its treatment on findings from its customized mechanical diagnosis and therapy assessmentdand radiofrequency neurotomy, which bases its treatments on findings from properly conducted diagnostic facet blocks. There is clearly no consensus that commonly used diagnostic tests hold any value in the decision-making process before offering a treatment for CLBP.

Indications for different treatment approaches

Table 1

page 5Table 2 summarizes the proposed indications and contraindications for each of the treatment categories as reported by the authors of these review articles. One of the first observations from this table is that the indications do not differ very much and provide very little information on when to consider a specific treatment approach. Indications for various interventions appear to fall into one of three broad categories: pain, nonspecific or mechanical CLBP, and failure of other treatments.

The presence of pain is noted as the main indication for articles on pharmacological approaches such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants, simple analgesics, opioid analgesics, adjunctive analgesics, and various nutritional supplements. Authors frequently noted that many of these medications are only approved for indications other than CLBP and therefore used off label with very little or no published evidence of efficacy. Clinicians must make a leap of faith that success noted in conditions such as diabetic neuropathy or pain in patients with terminal cancer can be translated to improving the symptoms of CLBP. Although the relative advantages/disadvantages of medication classes (eg, tricyclic antidepressants vs. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) were discussed, very little time was spent discussing why one medication in any particular drug class should be used over its competitors. There was therefore very little guidance to clinicians or consumers as to which medication should be considered beyond the opinion and experience of the prescribing clinician. Viewed together, these articles do suggest that certain nutritional supplements, NSAIDs, simple analgesics, and muscle relaxants can be used as a first-line approach to CLBP, with the consideration of adjunctive or opioid analgesics when pain is refractory.

A number of the treatments discussed in this special focus issue list the primary indication as nonspecific or mechanical CLBP. These include spinal manipulation and mobilization, massage, acupuncture, electrotherapeutic physical modalities, prolotherapy, traction, most of the exercise therapies, back schools, and patient education. Although vague, the description of nonspecific CLBP is perhaps the most honest statement regarding the indication of any intervention for CLBP given the doubts expressed above about the usefulness of advanced diagnostic testing for identifying the exact source of pain.

The third indication stated by authors to justify a particular procedure is that the patient has failed to respond to other treatment approaches, which was noted in many of the articles on injection or minimally invasive interventional procedures. This reasoning should be viewed with some concern because it has previously been used to support dubious treatments for other health conditions which simply cannot be cured. Although compelling, the simple fact that previous treatments have failed is not sufficient justification for exposing a patient to any treatment that is supported solely by weak evidence and which is associated with considerable costs and increased risks of harms. In fact, it could be argued that the burden of scientific proof should perhaps be even higher for so-called rescue therapies to prevent exposing patients to potential harms who may simply never respond positively to any interventions.

Comparing the evidence for efficacy

Table 1

page 8Table 3 is a summary of the evidence for efficacy which was reported by the authors in the 25 articles in this special focus issue. This table also presents the conclusions and recommendations based on the best available evidence considered by those authors. This table reports the number of studies discussed and does not reflect whether the studies were positive or negative for the intervention or whether the authors agreed with the results of these studies.

It is noted that the number and type of studies that were offered to support or provide evidence of efficacy or lack thereof varied considerably among the different treatment categories. The only interventions that reported being included in clinical practice guidelines on LBP were back schools and brief education, NSAIDs and simple analgesics, the McKenzie method, needle acupuncture, spinal manipulation and mobilization, trigger point injections, and watchful waiting (for acute LBP).

The five interventions where the authors reported the highest number of SRs were back schools (seven SRs), needle acupuncture (six SRs), tricyclic antidepressants (five SRs), prolotherapy (four SRs), and traction therapy (four SRs). The five interventions that authors reported the highest number of RCTs were needle acupuncture (19 RCTs), spinal manipulation and mobilization (13 RCTs), lumbar extensor strengthening exercises (11 RCTs), brief education (11 RCTs), and epidural steroid injections (10 RCTs). The five interventions where the authors relied primarily on OBSsdwhich include controlled clinical trials, prospective cohorts, and case seriesdwere Intradiscal Electrothermal Therapy (24 OBSs), minimally invasive nuclear decompression (nucleoplasty) (10 OBSs), medicine-assisted manipulation (6 OBSs), opioid analgesics (4 OBSs), and functional restoration (4 OBSs).

Although one might be tempted to correlate a large number of studies with a strong level of evidence from the scientific literature, this assumption would be an oversimplification. There were several possible reasons for reporting a high number of efficacy studies including 1) a few studies on each of several subtypes of interventions were combined into one broader category; 2) an intervention has a long history of use over which more studies have been conducted; 3) study eligibility criteria used by authors were more lenient; 4) multiple health databases were examined using a sensitive and comprehensive search strategy; 5) an intervention is controversial and has attracted the interest of researchers and funders; 6) conflicting results among studies perpetuate the need for additional research; or 7) lack of acceptance has motivated additional research to gain market share.

Although it appeared that studies with a higher number of SRs and RCTs generally reported positive findings supporting efficacy, best evidence syntheses from those review articles were often cautiously worded and offered only lukewarm recommendations on specific comparisons (eg, intervention vs. placebo), specific outcome measures (eg, pain but not function), or specific follow-up periods (eg, short term only). This may also have been a reflection of the experience and training in EBM of the authors involved, as mentioned earlier.

It was also noted that interventions discussing a high number of OBSs seemingly did so in the absence of higher level of evidence (eg, SRs or RCTs). Their articles also tended to make less nuanced and more positive recommendations. These findings lend themselves to two observations made regarding the interventions for CLBP reviewed in this special focus issue: 1) evidence of efficacy appears less ambiguous and more positive when based mostly on OBSs; and 2) recommendations become more restrained and conflicting when multiple SRs or RCTs are available to define boundaries regarding the conclusions that can be drawn from the scientific literature. In other words, the lower the quality and quantity of available research on an intervention, the higher the enthusiasm shown by clinicians for its efficacy. Stakeholders may wish to consider these possibilities when evaluating different treatment approaches for CLBP.

Reported harms from different interventions

Table 1

page 12Table 4 is a summary of the harms (eg, minor side effects, adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, complications) reported in the 25 articles in this special focus issue, and general estimates of their prevalence. Reported harms that have been associated with the interventions reviewed in this special focus issue varied considerably in nature, frequency, and severity. Commonly reported side effects included localized pain, soreness, or discomfort, mild gastrointestinal complaints with orally ingested therapies, and vague discomforts such as fatigue, weakness, or dizziness. The reported estimated prevalence of minor and usually brief side effects varied from 1% to 76%. More serious AEs included transient or permanent disc, vertebral, neural, or spinal cord injuries, which were more commonly reported with interventions requiring injections. All were described as rare, and usually based on isolated case reports or small case series.

It is difficult to form conclusions as to the relative safety of these interventions based on the harms reported by the authors. Although it is tempting to assume that interventions for which numerous possible harms were reported are inherently more dangerous that alternatives for which no harms are listed, this does not appear to be the case. Harmsdwhether theoretical or previously reporteddare possible with all of the interventions reviewed in this special focus issue. The most likely explanation for this discrepancy is that those authors who put more time and effort into searching and summarizing available evidence regarding harms were more likely to fully report their existence. Interventions for which few or no harms were reported likely performed only a cursory search for this information, or have simply not been studied sufficiently. To fully present the risks and benefits of available alternatives during the increasingly important informed consent process, clinicians must have access to more comprehensive research and reviews of harms than those presented by most authors in this special focus issue. Additional research related to the comparative harms of common interventions for CLBP is necessary before stakeholders can even consider this aspect in their decision-making process.

Conclusions

This special focus issue contains review articles written by clinicians and researchers who summarized the evidence on 25 classes of commonly used interventions for CLBP. The wealth of information provided by these articles cannot be understated and every article must be read in its entirety to appreciate the particular strengths and weaknesses of the arguments used by the authors for each treatment approach. It is also necessary for the reader to look at the entire special focus issue to obtain an overview of the different treatment options and place them in perspective. Although it was initially hoped that global recommendations regarding the use of specific interventions for CLBP could be made based on the information presented in each article, this goal has proven to elusive at this moment. When viewed as a whole, the articles in this special focus issue pose more questions than they answer. Taken together, these reviews demonstrate the serious deficiencies in the available research for many of the treatment approaches that are commonly used for CLBP because of either unavailable, insufficient, or conflicting research results. These articles do not present convincing evidence that it is currently possible to select one treatment approach over another for patients with CLBP and give very little guidance on when any specific treatment approach is indicated.

When viewed optimistically, the articles in this special focus issue do suggest that a reasonable approach to CLBP would include education strategies, exercise, simple analgesics, a brief course of manual therapy in the form of spinal manipulation, mobilization, or massage, and possibly acupuncture. In patients with longstanding or severe symptoms and psychological comorbidities, there is some evidence that a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach with cognitive behavioral treatment, fear-avoidance training, or functional restoration is at least as beneficial as surgery. This interpretation of the best available evidence is not materially different than the recommendations from the Practice Guidelines on Acute Low Back Pain in Adults that were published by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research in 1994. [2] Although potentially heartening to the many clinicians who have adopted aspects of this approach, it is somewhat disappointing to note that 14 years after dozens of highly promoted new interventions, thousand of studies, millions of lost work days, and billions of dollars spent on its care, so little has changed in the evidence available to guide stakeholders and support treatments for CLBP.

As noted in the review of the economic burden of LBP in this special focus issue, the magnitude of this problem is likely increasing in the United States and the question that needs to be answered is whether any treatment should be offered and widely used before there being sufficient research evidence to establish its efficacy, safety, and cost effectiveness. It is a generally accepted principle in most fields of health care that a treatment should not be offered to the public until there is sufficient evidence supporting its safety and effectiveness and a consensus by clinicians of different backgrounds as to its most appropriate indications and contraindications. It should be evident to most readers that this is not the norm when dealing with CLBP and additional research is required to achieve this long-term goal. In the interim, patients, clinicians, third-party payers, and policy makers have a responsibility to become thoroughly familiar with, critically appraise, compare, and openly discuss the best available evidence presented in this special focus issue. In this supermarket of over 200 available treatment options for CLBP, we are still in the era of caveat emptor (buyer beware). The enthusiastic support by providers of any treatment should be considered when reviewing available research evidence that supports its use. It is hoped that this special focus issue will provide a starting point for stakeholders desiring quality information to make decisions about the evidenceinformed management of CLBP.

References:

van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L.

Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group.

Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews

in the Cochrane collaboration back review group.

Spine 2003;28:1290–9.Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G, Brown K, Deyo R, Haldeman S.

Acute Low Back Problems in Adults: Clinical Practice Guideline No. 14

AHCPR Publication No. 95-0642: December 1994

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research,

Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services

Return LOW BACK PAIN

Return to EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Since 12-18-2022

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |