Clinical Presentation of a Patient

with Thoracic Myelopathy at

a Chiropractic ClinicThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Chiropractic Medicine 2012 (Sep); 11 (2): 115–120 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Charles W. Gay, Mark D. Bishop, and Jacqueline L. Beres

Graduate Research Assistant,

Rehabilitation Science Doctoral Program,

University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

INTRODUCTION: The purpose of this case report is to describe the clinical presentation, examination findings, and management decisions of a patient with thoracic myelopathy who presented to a chiropractic clinic.

CASE REPORT/METHODS: After receiving a diagnosis of a diffuse arthritic condition and kidney stones based on lumbar radiograph interpretation at a local urgent care facility, a 45–year-old woman presented to an outpatient chiropractic clinic with primary complaints of generalized low back pain, bilateral lower extremity paresthesias, and difficulty walking. An abnormal neurological examination result led to an initial working diagnosis of myelopathy of unknown cause. The patient was referred for a neurological consult.

RESULTS: Computed tomography revealed severe multilevel degenerative spondylosis with diffuse ligamentous calcification, facet joint hypertrophy, and disk protrusion at T9–10 resulting in midthoracic cord compression. The patient underwent multilevel spinal decompressive surgery. Following surgical intervention, the patient reported symptom improvement.

CONCLUSION: It is important to include a neurologic examination on all patients presenting with musculoskeletal complaints, regardless of prior medical attention. The ability to recognize myelopathy and localize the lesion to a specific spinal region by clinical examination may help prioritize diagnostic imaging decisions as well as facilitate diagnosis and treatment.

KEYWORDS: Spinal stenosis; Thoracic vertebrae

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Narrowing (stenosis) of the spinal canal may result in myelopathy anywhere along the spinal axis where the spinal cord is present. A common cause of acquired stenosis resulting in myelopathy is degenerative changes (spondylosis). [1] These pathological changes are the same in the thoracic spine as those changes found in the lumbar and cervical regions and increase with age, [2] yet the frequency of myelopathy as a result of these changes is less in the thoracic spine than in the cervical spine. [1, 3, 4] These opinions are based on clinical observations, small surgical cohorts, and case reports and not on large population studies. Consequently, much is still unknown about the point prevalence, morbidity, and financial and social costs of the insidious development of stenotic myelopathy due to thoracic spondylosis. In addition, the clinical presentation of thoracic spondylotic myelopathy presenting to nonsurgical clinics is not widely described. Unlike some other causes of thoracic myelopathy that may present acutely, degenerative spondylotic myelopathy progresses insidiously over a period of time, leading to varying clinical presentations. [1, 4, 5] Thoracic myelopathy is often a vague manifestation of a mixture of signs and symptoms including sensorimotor dysfunction in the trunk and/or lower extremities, diffuse and/or well-localized pain in the thoracic or lumbar regions, radiculopathy, and possible urinary disturbances. [1, 3, 4]

Unlike cervical myelopathy, where clinical presentations have been previously described in the chiropractic literature, no such chiropractic case reports exist for thoracic myelopathy. Therefore, the purpose of this case report is to describe a clinical presentation, examination findings, and management decisions for a patient with thoracic myelopathy.

Case Report

A 45–year-old white woman, employed as an aluminum construction contractor, presented to an outpatient chiropractic clinic with a primary complaint of low back pain accompanied by increasing paresthesia extending into the distal lower extremities bilaterally and difficulty walking over the last month. The patient reported being concerned because she “couldn't walk and her left leg dragged.” Although she stated no specific mechanism of injury, she reported that she had been experiencing intermittent bouts of worsening low back pain of 6 months' duration. The difficulty in walking was described as increased fatigue, general weakness, and increasing difficulty stepping over objects and ascending stairs. In addition, the patient reported sporadic giving way of the left knee during ambulation. The pain in the lumbar spine was reported as occurring daily with increasing intensity as the day progressed; it was rated as moderate to severe using a modified version of the McGill Pain Questionnaire where possible answers were no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, or severe pain. She quantified her pain as 7 of 10 on a numeric rating scale [11] with 0 equaling “no pain” and 10 equaling “the worst pain imaginable.” [6, 7]

The pain was described as cramping and was diffuse, encompassing the lower thoracic spine to the hips bilaterally, with intermittent radiation into the posterior thighs. Pain was made worse with getting into and out of a low car and being on her feet for long periods. She also described an associated intermittent “pins and needles” sensation that was present bilaterally with greater intensity on the left. She reported this sensation at an intensity of 9 of 10 using a modified numeric rating system, with 0 equaling “not present” and 10 equaling “most intensity imaginable.” The patient described her work requirements as moderately physically demanding, requiring a significant amount of daily driving and walking; and she described her work as highly stressful. Functional limitations were reported in walking and activities of daily living; specifically, she reported that she was unable to walk farther than 1 mile and had difficulty bending over and “getting around.” She had severe difficulty performing her work-related tasks, but indicated no difficulty with sleeping or lying down.

Two days before her presentation at the chiropractic clinic, the patient was seen in an urgent care facility. Records from the facility reported a history of insidious onset of generalized neck and back pain. Primary diagnostic testing consisted of lumbar radiographs that showed minimal degenerative changes in the lumbar spine and kidney stones. She was diagnosed with a diffuse arthritic condition and was prescribed anti-inflammatory and pain medications. The patient was instructed to follow up with her primary care physician for blood work and workup for potential renal stones observed on the radiographs.

The patient subsequently presented to the outpatient chiropractic clinic for evaluation, during which time the above history of present illness was obtained and further examination was completed. History was unremarkable for surgery, malignancy, or recent trauma. A review of systems revealed an increased urgency of urination over the last several weeks and prior diagnoses of carpal tunnel syndrome and anxiety disorder. In addition, she denied fever, chills, constitutional symptoms, and unexplained weight loss.

Physical examination revealed a mildly overweight, alert, well-oriented, and cooperative woman. The patient was afebrile. Blood pressure was 132/80 mm Hg on the left arm. Heart rate was 78 beats per minute. Height was 62 in. (1.57 m) and weight was 158 lb (71.67 kg).

Neurological examination revealed inability to perform heel and toe walking maneuvers. During observation of gait, a left-sided steppage pattern to compensate for left-sided foot drop/weakness was noted; initial contact on the left was with the forefoot. The patient was unable to maintain Romberg position with eyes closed. There was no evidence of pronator drift. Sensory examination to pinprick and light touch revealed no abnormalities.

Deep tendon reflexes were 2+ and symmetrical throughout, with the exception of the Achilles, which was hyperreflexive and graded as 3+/4+ bilaterally. Manual muscle testing including flexion and extension of the hip and knee and plantar flexion and dorsiflexion of the ankle and big toe revealed decreased motor strength globally in the left lower extremity, graded 4 out 5, as compared with a general 5 of 5 on the right. The plantar response was interpreted as up-going on the left and down-going on the right. The patient's primary low back pain was reproduced with Valsalva maneuver as well as seated and standing Kemp maneuvers. The patient's low back pain and left-sided buttock and posterior thigh pain were reproduced with left-sided Straight Leg Raise, left-sided Braggard maneuver, and Well Leg Raise.

The differential diagnosis at this time was based on the signs and symptoms of neurological compromise and included spinal myelopathy, but the origin or inciting lesion was still unknown. The primary suspects included a herniated nucleus pulposus in the cervical or lumbar regions, tumor or neurofibromatosis creating spinal cord compression, or a lesion of the cauda equina.

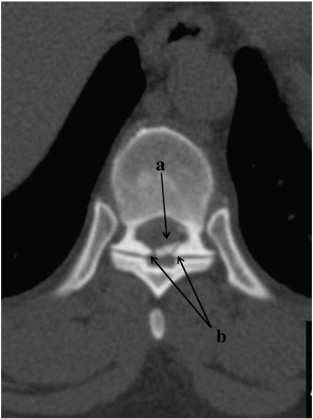

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3 Lumbar and cervical radiographs were ordered and revealed mild degenerative disk disease within the lumbar and cervical regions but no other significant abnormalities indicating the source of myelopathy. Following this initial evaluation, the findings and potential causes were discussed with the patient; and a referral for neurological consult and further diagnostic evaluation was made. The patient followed both initial recommendations, first following up with her primary care physician where blood work was conducted, revealing abnormality only in the form of elevated cholesterol, and second, a neurological consultation at which time a full-spine magnetic resonance was performed, indicating severe mid-thoracic stenosis.

Following the neurological consult, the patient was admitted to a local hospital where cervical and thoracic computed tomographies (CTs) were obtained. The cervical CT showed minimal degenerative changes. The thoracic spine CT report stated significant anterior and posterior ligamentous hypertrophy from T6–T10, facet arthropathy at T7–T9, and a generalized disk bulge that collectively created thecal sac and cord compression between T6 and T10 (Figures 1–3). The following day, the patient underwent multilevel thoracic spine decompressive surgery for thoracic myelopathy secondary to canal stenosis caused by degenerative spondylosis.

The surgeons performed multiple steps during the procedure. Microsurgical technique was used during T6–T7 decompressive laminectomy with medial facetectomy, bilateral T8–T9 and T9–T10 decompressive semilaminectomy with medial facetectomy, and left T8–T9 and T9–T10 diskectomy. Impaction of posterior osteophytes was performed at T6–T7 and T7–T8. Posterior instrumentation with pedicle screw fixation was performed bilaterally at T6–T10. Lamina autograft and demineralized bone matrix were used for posterior lateral fusion at T6–T10. The patient remained in the hospital for 6 days, after which time she was discharged with home health rehabilitation.

The patient was contacted via telephone for a follow-up interview 14 days after surgery. Specific questioning was used to determine pain and impairments. The patient reported that her low back pain and paresthesias had improved and that she no longer had the difficulty walking previously described. The patient in this case report gave consent to have personal health information published without divulging personal identifiers.

Discussion

Myelopathy secondary to spondylosis is less common in the thoracic spine as compared with the cervical or lumbar spines. Subsequently, cases of thoracic myelopathy presenting to chiropractic offices have not been previously reported in the literature.

Over the last 30 years, 28 patient case reports and 1 cohort of 132 patients with thoracic spondylotic myelopathy have been reported, all of whom were treated surgically. [1, 3, 4, 8–10] Barnett et a [l3] suggest that compressive myelopathy resulting exclusively from stenotic narrowing of the spinal canal from degenerative spondylosis in the thoracic region is rare in patients not also suffering from a generalized rheumatologic, metabolic, or orthopedic disorder or a history of trauma, and describes 6 such cases. However, Marzluff et al suggest that the condition is not as rare as previously thought, although these authors conceded that thoracic myelopathy is less prevalent than that in the cervical or lumbar regions. [9]

Without further epidemiological research of the disorder, it is difficult to estimate the number of patients that may present with this condition regardless of health care setting. Therefore, an understanding and appreciation of this condition are relevant for chiropractors because(1) Americans use chiropractic services primarily for ameliorating spine-related symptoms, particularly chronic pain, and

(2) patients with thoracic myelopathy may present with symptoms that can mimic other types of musculoskeletal disorders and can vary greatly. [11, 12]Although described as uncommon, thoracic myelopathy is a potential diagnosis for patients with abnormal neurologic findings.

The variable symptoms and general low suspicion level complicate diagnosing thoracic myelopathy, potentially leading to delays in treatment and additional diagnostic tests. In this case report, the neurologic evaluation performed by the chiropractic student intern identified ongoing abnormal neurological signs and, when combined with the patient's history, accurately established an initial working diagnosis of myelopathy. However, a more region-specific diagnosis was not made until after neurological referral and magnetic resonance imaging.

Although the sequence of events resulted in an accurate diagnosis, generally speaking, establishing a more precise working diagnosis that includes location is desirable, thus enabling diagnostic imaging to confirm or refute the diagnosis. In this case report, myelopathy may have been localized to the thoracic spine with additional maneuvers, thus establishing a more specific diagnosis.

A stepwise approach that considers the combination of presenting neurological findings can increase the precision of localizing the lesion in spinal disease, thus leading to more accurate diagnosis and treatments. Firstly, clinical findings of myelopathy must be recognized, which may include involvement of one or more neurologic levels, unilateral or bilateral complaints, sensory disturbances, motor weakness, disuse atrophy, spastic tone, hyperreflexia, wide-based gait, poor balance, presence of abnormal reflexes, and absence of superficial reflexes. [13–16]

Secondly, establish the presence or absence of neurological findings in particular regions. For example, a cranial nerve examination revealing intact cranial nerves with the absence of corticobulbar signs and absent jaw jerk reflex may reinforce the suspicion that the lesion lies below the foramen magnum. [17]

The presence of a scapulohumeral reflex is highest among cervical spine disorders affecting the high cervical region and above, with the reflex center presumed to be located between C1 and C3. [16] Thus, the absence of the scapulohumeral reflex may further assist localizing the lesion to below the C1–3 cord segments. [16] Furthermore, the absence of both Hoffman sign and motor, sensory, and reflex abnormalities in the upper extremities may further imply that the lesion exists below the cervical spine.

Moving into the thoracic region, the absence or markedly asymmetrical superficial abdominal reflex response may indicate an interruption in the pathway between the brain and the spinal cord at the thoracic level. The abdominal reflex divides the abdomen into quadrants; stimulation of the skin in each quadrant is performed tangentially toward the umbilicus. An abdominal muscle contraction results in a brisk motion of the umbilicus toward the stimulated quadrant. The absence or marked side-to-side asymmetry above the umbilicus indicates a problem at T8–T10 or above, whereas absence or marked asymmetry below the umbilicus indicates a lesion at T11–T12 or above. [13, 18]

Finally, spondylotic changes in the lower lumber region are not likely to create the upper motor neuron signs seen with myelopathy because the spinal cord terminates in the upper lumber spine in the majority of people. Instead, these changes are likely to result in lower motor neuron signs. Motor weakness and sensory disturbances are common in both situations; however, the myotatic reflexes and plantar response can differentiate the conditions. Hyperreflexia and the presence of an “up-going” toe are associated with upper motor neuron lesions, whereas hyporeflexia and the absence of an “up-going” toe are seen in lower motor neuron lesions.

The patient in this case was treated with surgical decompression, which is consistent with the other case reports and is the recommended treatment for cases of compressive thoracic myelopathy. [1, 3, 4, 8, 9] Future clinical research should investigate the potential role that nonpharmacological, nonsurgical treatments may serve in the management of this condition.

Despite having similar etiologies, treatment guidelines for spondylotic myelopathy vary depending of the location in the spine. Nonoperative, nonpharmacological treatment with careful regular monitoring for neurological deterioration is considered appropriate for patients with mild or subtle myelopathy. [15]

In addition, the natural history of cervical spondylotic myelopathy is quite variable with slow, stepwise decline or long periods of quiescence; thus, immediate surgical intervention for all patients is no longer considered appropriate by evidence-based standards. [14] There have been published case reports of patients with cervical compressive myelopathy comanaged successfully with nonsurgical medical treatments and different combinations of manual therapies including spinal manipulation, spinal mobilization, neural mobilization, and traction. [17, 19]

However, current treatment recommendations for thoracic myelopathy include only surgical approaches. There are no nonsurgical recommendations or case reports for conservative management of thoracic myelopathy. Future research should look to address the gap in clinical information surrounding the appropriate role of nonsurgical treatments for spondylotic thoracic myelopathy.

Limitations

Caution should be taken in applying this case study to typical clinical practice, as limitations are inherent within all case reports. Firstly, the description provided within this report may not represent the most common clinical presentation of thoracic myelopathy that will be seen in practice. Secondly, the results of the patient's response to the provided care may not be typical or a direct result of the care. Thirdly, it is presumed through the review of systems and physical examination that the patient was not concurrently suffering from generalized rheumatologic or metabolic disorders of bones and joints such as achondroplasia, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, osteochondrodystrophy, acromegaly, Scheuermann disease, osteofluorosis, or Paget disease that may have increased the risk of such a spondylotic myelopathy.3 However, these conditions were not specifically excluded through further diagnostic testing.

Conclusion

The clinical presentation, neurologic examination, and management of a patient with thoracic myelopathy are described in this case report. Although considered to be rare in clinical presentation, this case report should increase practitioner's awareness and understanding of thoracic myelopathy as a potential differential diagnosis in patients with musculoskeletal complaints and lower extremity neurological deficits in the presence of upper motor neuron signs.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

Funding was provided by NCMIC Foundation Educational Grant to Charles W. Gay. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

References:

Smith D.E., Godersky J.C.

Thoracic spondylosis: an unusual cause of myelopathy.

Neurosurgery. 1987;20(4):589–593

Kalichman L., Guermazi A., Li L., Hunter D.J.

Association between age, sex, BMI and CT-evaluated spinal degeneration features.

J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2009;22(4):189–195

Barnett G.H., Hardy R.W., Jr., Little J.R., Bay J.W., Sypert G.W.

Thoracic spinal canal stenosis.

J Neurosurg. 1987;66(3):338–344

Aizawa T., Sato T., Sasaki H.

Results of surgical treatment for thoracic myelopathy: minimum 2-year follow-up study in 132 patients.

J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7(1):13–20

Baron E.M., Young W.F.

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a brief review of its pathophysiology, clinical course, and diagnosis.

Neurosurgery. 2007;60(1 Supp1 1):S35–S41

Melzack R.

The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire

Pain. 1987;30(2):191–197

Hartrick C.T., Kovan J.P., Shapiro S.

The numeric rating scale for clinical pain measurement: a ratio measure?

Pain Pract. 2003;3(4):310–316

Abhaykumar S., Tyagi A., Towns G.M.

Thoracic vertebral osteophyte-causing myelopathy: early diagnosis and treatment.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(14):E334–E336

Marzluff J.M., Hungerford G.D., Kempe L.G., Rawe S.E., Trevor R., Perot P.L., Jr

Thoracic myelopathy caused by osteophytes of the articular processes: thoracic spondylosis.

J Neurosurg. 1979;50(6):779–783

Zhang H.Q., Chen L.Q., Liu S.H., Zhao D., Guo C.F.

Posterior decompression with kyphosis correction for thoracic myelopathy due to ossification of the ligamentum flavum and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament at the same level.

J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13(1):116–122

Coulter I.D., Hurwitz E.L., Adams A.H., Genovese B.J., Hays R., Shekelle P.G.

Patients Using Chiropractors in North America: Who Are They, and Why Are They in Chiropractic Care?

SPINE (Phila Pa 1976) 2002 (Feb 1); 27 (3): 291–298

Barnes PM , Bloom B , Nahin RL:

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children:

United States, 2007

US Department of Health and Human Services,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, 2008.Bono C.M., Garfin S.R.

Orthopaedic surgery essentials.

In: Bono C.M., Garfin S.R., editors. Spine.

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2004

Matz P.G., Anderson P.A., Holly L.T.

The natural history of cervical spondylotic myelopathy.

J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11(2):104–111

Mazanec D., Reddy A.

Medical management of cervical spondylosis.

Neurosurgery. 2007;60(1 Supp1 1):S43–S50

Shimizu T., Shimada H., Shirakura K.

Scapulohumeral reflex (Shimizu). Its clinical significance and testing maneuver.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18(15):2182–2190

Murphy D.R., Hurwitz E.L., Gregory A.A.

Manipulation in the Presence of Cervical Spinal Cord Compression: A Case Series

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006 (Mar); 29 (3): 236—144

Reeves A.G., Swenson R.S.

Chapter 8: reflex evaluation.

In: Swenson R.S.M.D.P., editor. Disorders of the nervous system: a primer.

Darthmouth Medical School; 2008.

http://www.dartmouth.edu/~dons/part_1/chapter_8.html

Available from: Accessed May, 2011

Browder D.A., Erhard R.E., Piva S.R.

Intermittent cervical traction and thoracic manipulation for management of mild cervical compressive myelopathy attributed to cervical herniated disc: a case series.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(11):701–712

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Since 10-15-2014

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |