Do Older Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain Differ

from Younger Adults in Regards to Baseline

Characteristics and Prognosis?This section was compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: European Journal of Pain 2017 (May); 21 (5): 866–873 ~ FULL TEXT

Manogharan S, Kongsted A, Ferreira ML, Hancock MJ.

Faculty of Medicine and Health Science,

Macquarie University,

Sydney, NSW, Australia.

BACKGROUND: Low back pain (LBP) in older adults is poorly understood because the vast majority of the LBP research has focused on the working aged population. The aim of this study was to compare older adults consulting with chronic LBP to middle aged and young adults consulting with chronic LBP, in terms of their baseline characteristics, and pain and disability outcomes over 1 year.

METHODS: Data were systematically collected as part of routine care in a secondary care spine clinic. At initial presentation patients answered a self-report questionnaire and underwent a physical examination. Patients older than 65 were classified as older adults and compared to middle aged (45-65 years old) and younger adults (17-44 years old) for 10 baseline characteristics. Pain intensity and disability were collected at 6 and 12 month follow-ups and compared between age groups.

RESULTS: A total of 14,479 participants were included in the study. Of these 3,087 (21%) patients were older adults, 6,071 (42%) were middle aged and 5,321 (37%) were young adults. At presentation older adults were statistically different to the middle aged and younger adults for most characteristics measured (e.g. less intense back pain, more leg pain and more depression); however, the differences were small. The change in pain and disability over 12 months did not differ between age groups.

CONCLUSIONS: This study found small baseline differences in older people with chronic LBP compared to middle aged and younger adults. There were no associations between age groups and the clinical course.

SIGNIFICANCE: Small baseline differences exist in older people with chronic low back pain compared to middle aged and younger adults referred to secondary care for chronic low back pain. Older adults present with slightly less intense low back pain but slightly more intense leg pain. Changes in pain intensity and disability over a 12 month period were similar across all age groups.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is responsible for a substantial burden on the community, economy and the health care systems (Walker et al., 2003; Murray et al., 2013). Back pain is the most common health condition forcing older Australians to retire involuntarily and this problem reduces Australia’s GDP by $3.2 billion per annum (Schofield et al., 2008). According to the World Health Organisation low back pain is one of the most disabling conditions among the elderly (World Health Organization, 2009).

Although LBP in older adults is recognized as a common and physically disabling condition it is poorly understood because the vast majority of the LBP research has focused on the working aged population from 18 to 65 (Schiottz-Christensen et al., 1999; Paeck et al., 2014). Patients aged over 65 are often excluded from studies and only a small number of studies have studied LBP in older adults (Scheele et al., 2012; Paeck et al., 2014). The findings in younger populations cannot necessarily be generalized to older people with LBP (Scheele et al., 2014). The United Nations predicts by 2050 people aged 60 and older will account for 20% of the world’s population and one-fifth of this population will be above 80 years of age (Lutz et al., 2008). With the increase in the ageing population and the lack of studies currently available that focus on LBP in older people, large cohort studies are needed to gain a better understating of LBP in the older population.

Previous studies are mixed in their findings regarding LBP in older adults and how it compares to younger adults. Some studies suggest that older people experience a higher prevalence of severe low back pain and/or disabling episodes but report less frequent benign or mild pain (Cayea et al., 2006; Scheele et al., 2014). A cross-sectional populationbased study revealed that those aged over 80 years were twice as likely to be disabled by an episode of LBP as those aged 25–40 (Macfarlane et al., 2012). The international BACE (Back Complaints in the Elders) consortium is recruiting a cohort of patients >55 years of age presenting for care with a new episode of LBP (Scheele et al., 2011). This cohort will provide valuable data on LBP in older people; however, it does not include younger adults to enable direct comparison within the same study.

Studies that include both older and younger adults with LBP are ideal to investigate potential differences in low back pain between older and younger people. Potential difference in LBP in older people could manifest as either differences in presentation and/or differences in prognosis. A better understanding of these potential differences between older and younger people with low back pain is critical to understanding how to optimize management of LBP in older people and whether or not a different approach is required compared to younger adults.

Therefore, the broad aim of the study is to compare LBP in older adult patients with LBP in younger adult patients to assess if important differences exist. Specifically, the aims of the study are to(1) compare the initial presentation of older adults and younger adults with chronic LBP attending a secondary spine care centre in Denmark and

(2) compare the prognosis over 1 year of older adults and younger adults in this cohort.

Methods

Study design

This study is based on data collection from the SpineData database (Kongsted et al., 2012, 2014; Kent et al., 2015). It includes both a cross-sectional study of patient presentation and a longitudinal study of patient outcomes. The regional ethics committee of Southern Denmark (Project ID S-200112000-29) reviewed the protocol for the original study and stated that it according to Danish law did not need ethical approval due to the observational design.

Study setting

Data were collected as part of routine clinical practice in a secondary, non-surgical, outpatient Spine Center in The Region of Southern Denmark (Kongsted et al., 2012, 2014). The Spine Center performs multidisciplinary, structured physical examinations and treatment planning for patients with spinal pain referred from general practitioners, chiropractors and medical specialists. Patients referred to the centre have received treatment in primary care without a satisfactory outcome. Participants were asked to participate in a follow-up questionnaire at 6 and 12-months. An electronic questionnaire was accessed through a link sent by email or people could opt to have a postal survey.

Data collection

Data were collected in the Spine Center’s electronic clinical registry named the SpineData database. Participants answered a comprehensive self-reported questionnaire on a touch screen in the waiting area preceding their first consultation. The data were entered directly into the SpineData database.

Study sample

We used the following criteria to select patients from the SpineData database for this study. All patients in the database aged 17 or older who were seen at The Spine Centre between January 1st 2012 and December 31st 2013 with LBP as their main complaint and who gave informed consent for their data to be used for scientific purposes were included in this study. Only patients with follow-up data for either 6 or 12 months were included in the longitudinal study (aim 2).

Predictor variable

The key variable of interest in this study was participant age. Patients were categorized into three age groups. Older age was defined as those >65 years of age at the time they presented to the Spine centre. Other participants were categorized into middle aged (45–65) and younger (18–44) to serve as two comparison groups for the older adults.

Outcome variablesOutcomes for cross-sectional study (aim 1) We investigated the differences between older adults and the two groups of younger adults on the 10 baseline measures listed below. The evidence base for the SpineData variables has been previously published (Kent et al., 2015).

Outcomes for longitudinal study (aim 2) Low back Pain Intensity and disability were measured at 6 and 12-month follow-up using the same methods as described for baseline measures.Duration of present episode. Duration was measured in months and categorized into three groups 0–3 months,

3–12 months and >12 months.

Previous LBP episodes. Scored as yes or no in response to question ‘Have you had previous low back pain episodes?’

Intensity of LBP. Average of ‘LBP now’, ‘worst in the last 14 days’ and ‘typical in the last 14 days’

on 0–10 Numerical Rating Scales (NRS).

Leg pain intensity. Measured in a similar manner to intensity of LBP.

Proportion with leg pain below the buttock. Using the body charts completed at baseline patients were classified as

having ‘No leg pain’ or ‘leg pain below the buttock’.

Disability. Self-reported disability was measured with the 23-item Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ)

converted to a score out of 100 (where 0% = no activity limitation and 100% = maximum activity limitation).

Patients needed to answer at least 17 questions for the score to be included and the %-score calculated based

on the number of items completed (Kent and Lauridsen, 2011).

Depression. Two Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders screening questions were used to determine

if depression was present.(1) ‘During the past month have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?’ and

(2) ‘During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?’Both questions were measured on the 0–10 NRS, where 0 represented never and 10 represented always.

A mean was calculated, and depression was considered to be present if both scores were >6 out of 10.

These cut off scores have been validated in this setting relative to the Major Depression Inventory

(Kent et al., 2014).

Fear of movement. Measured using 0–10 NRS (proportion with a total score on two screening questions

from the Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire equal to or above 14). This threshold has been validated

in this setting relative to the physical activity subscale of the Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire

(Kent et al., 2014).

Self-reported general health. Assessed with the EuroQol Health Thermometer where participants

rate their own health at the present time. It was expressed on a scale of 0–100, where 0 was the

worst health state and 100 is the best health state

(Williams and Williams, 1990).Data analyses

Cross-sectional part (aim 1) Dichotomous baseline characteristics were described as proportions (95% confidence intervals (CI)) and continuous baseline characteristics were described as means (95% CI) or medians (IQR) if continuous variables were not normally distributed. Pairwise comparisons between older age group and the two younger age groups for each baseline characteristic were tested using t tests for continuous normally distributed variables, and a Mann–Whitney U-test for variables with a non-normal distribution. Chi- Square Tests were used to compare proportions. Group differences were considered significantly different at p < .05.

Longitudinal part (aim 2) Longitudinal models using a Linear Mixed Model were used to analyse if older patients had different outcomes to the two younger adult groups in terms of pain and disability at 6 and 12-months. These models take into account that the repeated outcome measures are correlated. The outcome measures (pain and activity limitation) were treated as continuous measures. The age variable was introduced in the model as a 3-level categorical variable with old age as the reference category. The time variable was introduced into the model as a categorical number of months. The primary analysis involved a simple model with no other covariates. We also ran 2 secondary analyses where we first entered gender and duration of low back pain, and then also added depression and fear of movement, to assess if these explained any differences observed between different age groups on pain and disability outcomes. Pairwise comparisons of absolute scores on 6- and 12-months outcomes between the older age group and the 2 younger age groups were performed in the same way as the baseline comparisons. Analyses were performed using STATA 14.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA) 4905 Lakeway Drive; College Station, Texas 77845 USA.

Results

Between January 1st 2012 and December 31st 2013 14,567 people presented to the spine centre with LBP as their main complaint and were registered in the database. After excluding those aged 16 or younger 14,479 patients were included in the study. Of these 5321 (37%) were aged 17–44 (median 36, IQR 29–41), 6071 (42%) were aged 45–65 (median 54, IQR 49–59) and 3087 (21%) patients were aged >65 (median 72, IQR 68–76). There were slightly more females (55%) and the mean age was 51.

Study aim 1: baseline differences

Table 1 Patient baseline characteristics for all three age groups are summarized in Table 1. The older aged group was statistically different to the younger aged group for almost all baseline measures (proportion female, back pain intensity, leg pain intensity, previous episodes, pain below buttock, general health, disability, depressive symptoms and fear of movement). The older age group was statistically different to the middle aged group for the baseline measures of proportion female, back pain intensity, leg pain intensity, previous episodes, pain below buttock and depressive symptoms. Older adults tended to have slightly lower average back pain intensity, but slightly higher average leg pain intensity and disability. A slightly higher percentage of older adults had pain extending below the buttock, and a smaller proportion was fear avoidant or depressed as compared to the young adult group. However, all differences were small in size.

Study aim 2: 6 and 12 month outcome differences

Table 2

Table 3

Figure 1

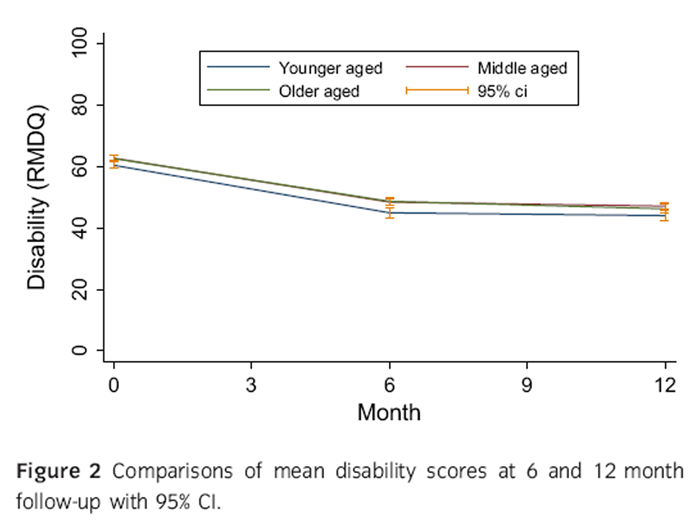

Figure 2 Either the 6 month or the 12 month follow-up was completed by 48% (6995/14,479) and 46% (6705/ 14,479) of participants for pain intensity (37% at 6 months and 34% at 12 months) and disability (36% at 6 months and 33% at 12 months), respectively, and included in the longitudinal analyses. The proportion of patients not responding to any of the follow-ups was largest in the youngest age group and smallest in the older age group (younger aged 65% drop-out, middle aged 46%, older age 37%; p < 0.01). Differences in baseline characteristics between responders and drop-outs were small although drop-outs were less likely to have had previous episodes and more likely to have depressive symptoms or fear of movement (Table 2). The differences between responders and drop-out were not statistically different across age groups apart from women being less likely to drop-out in the youngest age group and more likely to drop-out in the oldest age group. Also, middle aged and older adults who dropped out had on average longer episode durations than the responders, whereas that was not the case in the young group (Table 2).

Average pain intensity for the three different age groups at each time point are provided in Table 3 and represented visually in Figure 1. Older adults had significantly lower average back pain intensity than both younger and middle aged participants; however, the differences were small. The interaction between time and age in the longitudinal linear mixed model was non-significant when comparing older participants to either middle aged (p = 0.967) or younger participants (p = 0.254), suggesting that age did not result in a difference in change in pain intensity over time. The findings were very similar in both secondary analyses where we first entered gender and duration of the episode, and then also added depression and fear of movement into the model.

Average disability (RMDQ) for the three different age groups at each time point is provided in Table 3 and represented visually in Figure 2. Older participants had significantly more disability than younger adults at 6 months but not at 12 months. There were no significant differences between disability in older adults and middle aged adults at either 6 or 12 months. The interaction between time and age in the longitudinal linear mixed model was non-significant when comparing older participants to either middle aged (p = 0.479) or younger participants (p = 0.129), suggesting that age did not result in a difference in change in disability over time. The findings were very similar in both secondary analyses where we first entered gender and duration of the episode, and then also added depression and fear of movement into the model.

Discussion and conclusions

Principle findings

We found baseline differences existed between older adults with chronic LBP and young or middle aged adults with chronic LBP. However, while many differences were statistically significant, the size of the differences in outcome measures was small and mostly unimportant. Older adults did present with slightly less intense LBP but slightly more intense leg pain. Consistent with this finding the percent of older participants describing pain extending below the buttock was a little higher than in the middle aged or younger adults.

At 6- and 12-month follow-up back pain intensity was slightly lower in the older adults compared to both middle aged and younger adults. Disability outcomes at 6 and 12 months were marginally higher in older adults when compared to younger adults, but not different to middle aged adults. Changes in pain intensity and disability over the 12 month period were similar across all age groups.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Strengths of this study include the large sample of consecutive patients presenting for care enabling direct comparison between older adults and 2 comparison age groups from the same clinical population. The data were collected as part of routine care therefore likely increasing the generalizability of the findings. However, our sample included Danish people with chronic low back pain presenting to a secondary care spine clinic and it is unclear how well our findings would generalize to primary care or other more diverse geographical regions.

The key limitation of this study is the low percent of participants that completed follow-up questionnaires. We have previously shown that patients in this cohort who completed follow-up were very similar at baseline to those who did not (Kent et al., 2015). There is no consensus on what age is considered older and it is possible the results could be different if a different threshold for age was used. We selected >65 as this age has commonly used to exclude older adults and as such this is the age group with low back pain for whom little is known.

A further limitation of this study is that some of the baseline characteristics we investigated (e.g. depression) were collected using single item screening questions rather than multi item tools. These screening questions have been demonstrated to represent full questionnaires well and are an effective way to gather information when questions on many aspects of health are asked in a clinical setting (Kent et al., 2014). It is possible that there were unmeasured confounders that may influence the relationship between age and the study outcomes; however, our study aimed to describe any differences observed between age groups but did not aim to explore causal pathways.

Comparison to other studies

A recent publication from the Back pain Outcomes Longitudinal Data (BOLD) cohort presented baseline characteristics of over 5000 adults with low back pain presenting for care (Jarvik et al., 2014). Despite the different setting the baseline pain intensity was relatively similar (5.0 on a 0–10 point scale) to our secondary care cohort. As the BOLD cohort does not include a younger comparison group it is not possible to assess if the small differences we observed in most baseline variables also occurred in this primary care setting.

The BACE cohort study examined the differences in baseline characteristics between patients with low back pain aged 55–74 years and those aged ≥75 years (Scheele et al., 2014). They found patients aged >75 years reported more disability and more psychological health problems. These findings are somewhat different to our findings that disability was no different between our middle aged group and older group and also that presence of depression was lowest in our older group. The differences might be explained by the different age threshold used, the different setting or the different duration of participants’ back pain (only approximately 25% of participants in BACE had back pain lasting longer than 3 months).

It is possible that low back pain in those over 75 results in greater disability than in our group who were over 65. The population-based MUSICIAN study (Macfarlane et al., 2012) reported that while prevalence of LBP peaked at 41–50 years of age the rates of more severe disabling LBP increased with age and were approximately twice as high in those over 80 years of age compared to those 40 or younger. This study also reported that older people were less likely to have been referred to physiotherapy or a specialist which could explain some differences between our clinical cohort and this population-based cohort. In our secondary care cohort, the proportion of people aged over 65 was 21%, however, we do not know how this compares with people presenting to primary care or whether referral to Danish secondary care is triggered by other factors in older compared to younger adults.

Meaning of the study

The small size of any differences identified between our older group and younger adults suggest that while older adults with LBP do appear to have some differences to younger adults with LBP the differences may not be that important. The slightly higher prevalence and intensity of leg pain may represent a greater degree of neurological involvement in older adults due to degenerative stenosis. We found no differences in change over time for either pain or disability suggesting the prognosis of older adults with chronic LBP is similar to that of younger adults.

Our study does not answer the question of whether older people with low back pain respond differently to specific interventions than younger adults with low back pain, but the similar prognosis and minimal differences in baseline do not support this hypothesis. There is no strong evidence to suggest older adults with LBP respond better to any particular intervention than younger adults with LBP (Ferreira et al., 2014). Despite this the MUSICIAN study found older people were more likely to be opioid users and less likely to be prescribed exercise than younger adults (Macfarlane et al., 2012).

Conclusion

This study found statistically significant baseline differences in older people with chronic LBP compared to middle aged and younger adults referred to secondary care with LBP. Older people generally had lower back pain intensity, higher prevalence and severity of leg pain, and lower levels of depression. However, given the small size of these differences their clinical importance is questionable. There were no differences in change in pain or disability over a 12 month period between older adults with LBP and younger adults with LBP.

Author contributions

All authors (1) made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; (3) approved the version submitted.

References:

Cayea, D., Perera, S., Weiner, D.K. (2006).

Chronic low back pain in older adults: What physicians know, what they think they know,

and what they should be taught.

J Am Geriatr Soc 54, 1772–1777Ferreira, M.L., Ferreira, P., Henschke, N., Kamper, S., Koes, B. (2014).

Age does not modify the effects of treatment on pain in patients with low back pain:

Secondary analyses of randomized clinical trials.

Eur J Pain 18, 932–938Jarvik, J.G., Comstock, B.A., Heagerty, P.J., Turner, J.A., Sullivan, S.D., Shi, X. (2014)

Back pain in seniors: The Back pain Outcomes using Longitudinal Data (BOLD) cohort baseline data.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15, 134Kent, P., Lauridsen, H.H. (2011).

Managing missing scores on the Roland Morris disability questionnaire.

Spine 36, 1878–1884Kent, P., Mirkhil, S., Keating, J., Buchbinder, R., Manniche, C., Albert, H.B. (2014).

The concurrent validity of brief screening questions for anxiety, depression, social isolation,

catastrophization, and fear of movement in people with low back pain.

Clin J Pain 30, 479–489B., Manniche, C. (2015).

SpineData–a Danish clinical registry of people with chronic back pain.

Clin Epidemiol 7, 369–380Kongsted A, Kent P, Albert H, Jensen TS, Manniche C.

Patients with Low Back Pain Differ From Those Who Also Have Leg Pain or Signs of Nerve Root

Involvement - A Cross-sectional Study

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012 (Nov 28); 13: 236Kongsted, A., Vach, W., Axø, M., Bech, R.N., Hestbaek, L., Kongsted, A. (2014).

Expectation of Recovery from Low Back Pain: A Longitudinal Cohort

Study Investigating Patient Characteristics Related to Expectations

and the Association Between Expectations and 3-month Outcome

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014 (Jan 1); 39 (1): 81–90Lutz, W., Sanderson, W., Scherbov, S. (2008).

The coming acceleration of global population ageing.

Nature 451, 716–719Macfarlane, G.J., Beasley, M., Jones, E.A., Prescott, G.J., Docking, R., Keeley, P. (2012).

The prevalence and management of low back pain across adulthood:

Results from a population-based cross-sectional study (the MUSICIAN study).

Pain 153, 27–32Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al.

Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010:

a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

Lancet 2013 Dec 15;380(9859):2197–223.Paeck, T., Ferreira, M.L., Sun, C., Lin, C.W.C., Tiedemann, A., Maher, C.G. (2014).

Are older adults missing from low back pain clinical trials? A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Arthritis Care Res 66, 1220–1226Scheele, J., Luijsterburg, P.A., Ferreira, M.L., Maher, C.G., Pereira, L., Peul, W.C., van Tulder, M.W. (2011).

Back complaints in the elders (BACE); design of cohort studies in primary care: An international consortium.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12, 193Scheele, J., Luijsterburg, P., Bierma-Zeinstra, S., Koes, B. (2012).

Course of back complaints in older adults: A systematic literature review.

Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 48, 379–386Scheele, J., Enthoven, W., Bierma-Zeinstra, S., Peul, W., Tulder, M., Bohnen, A. (2014).

Characteristics of older patients with back pain in general practice:

BACE cohort study.

Eur J Pain 18, 279–287Schiottz-Christensen, B., Nielsen, G.L., Hansen, V.K., Schodt, T., Sorensen, H.T. (1999).

Long-term prognosis of acute low back pain in patients seen in general practice:

A 1-year prospective follow-up study.

Fam Pract 16, 223–232Schofield, D.J., Shrestha, R.N., Passey, M.E., Earnest, A., Fletcher, S.L., Schofield, D.J. (2008).

Chronic disease and labour force participation among older Australians.

Med J Aust 189, 447–450Walker, B.F., Muller, R., Grant, W.D. (2003).

Low back pain in Australian adults: The economic burden.

Asia Pac J Public Health 15, 79–87Williams, A., Williams, A. (1990).

EuroQol – A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life.

Health Policy 16, 199–208World Health Organization (2009).

Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks

(Geneva: WHO Press).

Return to SENIOR CARE

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Since 4–10–2017

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |