Does Maintained Spinal Manipulation Therapy

for Chronic Non-specific Low Back Pain

Result in Better Long Term Outcome?This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011 (Aug 15); 36 (18): 1427–1437 ~ FULL TEXT

Senna, Mohammed K. MD; Machaly, Shereen A. MD

Shereen A. Machaly, MD,

Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Department,

Mansoura Faculty of Medicine,

Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

This new, single blinded placebo controlled study, conducted by the Mansoura Faculty of Medicine, conclusively demonstrates that maintenance care provides significant benefits for those with chronic low back pain.

Egyptian Study Shows Maintenance Care Helpful in Chronic

Low Back Pain Treatment

FROM: Health Insights Today

In the first study of its kind, researchers at the Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Department at the Faculty of Medicine at Mansoura University in Egypt conducted a prospective single blinded placebo controlled study to assess the effectiveness of spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) for the management of chronic non-specific low back pain (LBP) and to determine the effectiveness of maintenance SMT in long-term reduction of pain and disability levels associated with chronic low-back conditions after an initial phase of treatments.

The investigators noted that numerous clinical trials have attempted to evaluate its effectiveness for different subgroups of acute and chronic LBP but the efficacy of maintenance SMT in chronic non-specific LBP has not been studied.

[Editor's Comment: Actually, the effect of Maintenance Care/Preventive Care SMT

on chronic LBP was explored by Descarreaux in a virtually identical 2004 JMPT study]

Sixty patients with chronic, nonspecific LBP lasting at least 6 months were randomized to receive either(1) 12 treatments of sham SMT over a one-month period,

(2) 12 treatments, consisting of SMT over a one-month period, but no treatments for the subsequent nine months, or

(3) 12 treatments over a one-month period, along with “maintenance spinal manipulation” every two weeks for the following nine months.

To determine any difference among therapies, they measured pain and disability scores, generic health status, and back-specific patient satisfaction at baseline and at 1-month, 4-month, 7-month and 10-month intervals. Results were as follows: patients in second and third groups experienced significantly lower pain and disability scores than first group at the end of 1-month period (P = 0.0027 and 0.0029 respectively). However, only the third group that was given spinal manipulations during the follow-up period showed more improvement in pain and disability scores at the 10-month evaluation. In the no maintained SMT group, however, the mean pain and disability scores returned back near to their pretreatment level. Other key findings were that (a) after 1 month, both the SMT and SMT+Maintenance care cohorts showed a significant improvement in spinal flexion and bending, and (b) after 10 months, the SMT+Maintenance care cohort alone showed significant improvements in both spinal flexion and bending and the global assessment scale.

The authors concluded that spinal manipulation is effective for the treatment of chronic nonspecific LBP and that to obtain long-term benefit for the patient, this study suggests maintenance spinal manipulations after the initial intensive manipulative therapy can provide that additional benefit.Study Design: A prospective single blinded placebo controlled study was conducted.

Objective : To assess the effectiveness of spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) for the management of chronic non-specific low back pain (LBP) and to determine the effectiveness of maintenance SMT in long-term reduction of pain and disability levels associated with chronic low-back conditions after an initial phase of treatments.

Summary of background: SMT is a common treatment option for low back pain. Numerous clinical trials have attempted to evaluate its effectiveness for different subgroups of acute and chronic LBP but the efficacy of maintenance SMT in chronic non-specific LBP has not been studied.

Subjects and Methods: 60 patients with chronic, nonspecific LBP lasting at least 6 months were randomized to receive either:(1) 12 treatments of sham SMT over a one-month period,

(2) 12 treatments, consisting of SMT over a one-month period, but no treatments for the subsequent nine months, or

(3) 12 treatments over a one-month period, along with "maintenance spinal manipulation" every two weeks for the following nine months.To determine any difference among therapies, we measured pain and disability scores, generic health status, and back-specific patient satisfaction at baseline and at 1-month, 4-month, 7-month and 10-month intervals.

Results: Patients in second and third groups experienced significantly lower pain and disability scores than first group at the end of 1-month period (P = 0.0027 and 0.0029 respectively). However, only the third group that was given spinal manipulations during the follow-up period showed more improvement in pain and disability scores at the 10-month evaluation. In the no maintained SMT group, however, the mean pain and disability scores returned back near to their pretreatment level.

Conclusion SMT is effective for the treatment of chronic non specific LBP. To obtain long-term benefit, this study suggests maintenance spinal manipulations after the initial intensive manipulative therapy.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common musculoskeletal ailment worldwide. It affects up to 80% of the adult population at some point during their lives. [1] A simple and practical classification, divided LBP into three main categories, the so-called “diagnostic triage” [2]: specific spinal pathology, nerve root pain/radicular pain and nonspecific LBP. Chronic LBP is defined as LBP persisting for at least 12 weeks. [3] “Nonspecific” chronic LBP is the LBP that is not attributable to a recognizable, known specific pathology (such as infection, tumor, osteoporosis, fracture, structural deformity, inflammatory disorder, for example, ankylosing spondylitis, radicular syndrome, or cauda equine syndrome). Nonspecific LBP represents about 85% of LBP patients seen in primary care. [4] About 10% will go on to develop chronic, disabling LBP. [5] It is this group of LBP that uses the majority of health care and socioeconomic costs. [6, 7]

Many reviews evaluated the role of spinal manipulation (SM) as a treatment of LBP. The majority of these reviews concluded that SM is an efficacious treatment for nonspecific LBP. [8–13] However, most reviews restricted their positive conclusions to patients with acute nonspecific LBP. Some studies suggest that patients with chronic nonspecific LBP are likely to respond to SM. [14] A recent high quality review of literature stated that Cochrane review found SM moderately superior to sham manipulation for chronic LBP. [15] However, research evidence, [16] recognizes that not all patients with LBP should be expected to respond to a manipulation intervention. Thus, the debate whether or not SM constitutes an efficacious treatment continues. [17]

Most of the studies concerned about the therapeutic effects of SM investigated theses effects only for short term. One possible way to reduce the long-term (<6 months) effects of LBP is maintenance care (or preventive care). [18] In a previous study, manipulated patients with chronic nonspecific LBP had improved within 2 weeks and after this time, new cases of improvement occurred for every visit, and at the 12th visit, approximately 75% of the patients had improved. [19] Another study found that the thrust manipulation-treated group of patients showed the best outcome compared with the no manipulation and nonthrust manipulation patients with improved pain and 66% reduction in Oswestry scores over a period of 4 sessions and by the end of 12 sessions further improvement was obtained. [20] This raises the question if, the more the sessions offered the greater the improvement achieved, so it is hypothesized that if spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) can be maintained for longer periods, it will be more beneficial in maintaining the desirable outcomes obtained after short-term treatment. However, studies investigating the role of maintained manipulation in reducing pain and disability associated with chronic nonspecific LBP are lacking. To the best of our knowledge, no one had searched this concept except one study of Descarreaux et al [21] who reported the positive effects of continued manipulation treatment in maintaining functional capacities and reducing the number and intensity of pain episodes after an acute phase of treatment.

The goal of this study was to assess the effectiveness of SMT for the management of chronic nonspecific LBP and to determine the effectiveness of maintenance SMT in long-term reduction of pain and disability levels associated with chronic low back conditions after an initial phase of treatments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

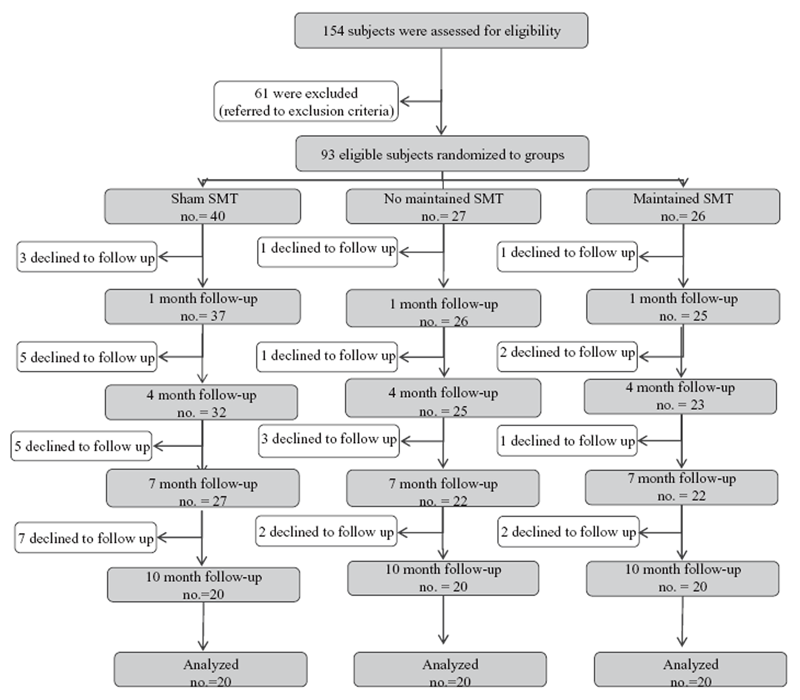

Eligible subjects were patients aging between 20 and 60 years with chronic nonspecific LBP (that lasted for at least 6 months). A total of 154 patients were examined, 61 patients were excluded whereas 93 patients were eligible and enrolled in this study. Patients with “red flags” for a serious spinal condition (e.g. , tumor, compression fracture, infection), signs consistent with nerve root compression (i.e. , positive straight leg raise >45 ° , or diminished reflexes, sensation, or lower extremity strength), structural deformity, spondylolithesis, spinal stenosis, ankylosing spondylitis, osteoporosis, prior surgery to the lumbar spine or buttock, obvious psychiatric disorders, referred pain to the back, widespread pain (e.g. , fibromyalgia), obese patients, current pregnancy, patients older than 60 years or younger than 20 years, and patients who had previous experience with SMT were excluded.

All patients were recruited from the Outpatient Clinics of Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Department in Mansoura University Hospital , which is one of the major university hospitals, treating large number of patients with different causes of LBP in a specialized outpatient clinic dedicated for back pain. The physicians conducting the trial are MD certified, well-trained, have been in practice for more than 10 years with good experience in managing LBP, and they are staff members of Rheumatology & Rehabilitation Department, Mansoura University.

All patients underwent a standardized baseline evaluation before treatment consisted of detailed history taking and physical examination. Subjects were asked to identify the mode and date of onset of their LBP. Also, patients were asked for present symptoms suggestive of specific spinal disease, prior back therapy (including manipulation or surgery), or prolonged use of corticosteroids. All patients underwent local musculoskeletal examination as well as full neurologic examination. Blood sample was withdrawn from every patient and sent to the laboratory for complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein analysis. Lateral and anteroposterior radiograph films followed by magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine were also taken in an attempt to rule out the specific diseases of the lumbar spine.

Group Classification and Procedures

Figure 1 After the baseline evaluation, the eligible patients were assigned randomly to one of three groups matched for age and sex. The study was initially designed to include three groups; the first (control) group comprises more patients than the other two groups as we presumed that patients who may not complete the trial will mostly belong to this group. It was planned to randomize 40%, 30%, and 30% of patients to the first, second, and third groups, respectively. Patients allocation is shown in Figure 1.

Randomization was performed using sequential-sealed envelopes prepared before enrollment of the patients. Patients were randomized twice, first for the treating clinician and second for the treatment group. Then, first envelope was opened, and only the treating fellow subsequently opened the sealed second envelope and recorded the allocation of patients as they entered the trial. Patients who were manipulated by one physician were assessed throughout all the trial follow-up intervals by the other physician who was completely blind to group assignment of patients being assessed. Patients were not allowed to talk about the type of care they received.

After randomization patients started the first phase treatment (1-month period). During this phase, all participants are informed about back instructions and received 12 sessions of manipulation (or sham manipulation) followed by back exercise in form of pelvic tilt range of motion (ROM) exercise.

The first group (age range: 21–53 years) received 12 treatments consisting of sham SM using minimal force over a 1-month period (control group), but no treatments for the subsequent 9 months. The second group (age range: 23–48 years), received 12 treatments consisting of standardized SM three times weekly over a 1-month period, but no treatments for the subsequent 9 months (nonmaintained SMT group). The third group (age range: 20–50 years), also received same intensive treatment of SM as second group over a 1-month period “initial intensive SMT,” along with “maintenance SMT” every 2 weeks for the next 9 months (maintained SMT group).

Clinical Interventions

Subjects in second and third groups received the same manipulation technique. SM is defined as a high velocity thrust to a joint beyond its restricted range of movement. [22]

The manipulation technique is performed with the patient supine. The side to be manipulated first will be the more symptomatic side on the basis of the patient’s complaint followed by manipulation of the opposite side. If the patient cannot specify a more symptomatic side, the therapist may select either side for manipulation. The therapist stands on the side opposite of that to be manipulated. The patient is passively moved into side-bending toward the side to be manipulated (the patient will lie with the more painful side up). The patient interlocks the fingers behind his or her head. The therapist passively rotates the patient, and then delivers a quick thrust to the anterior superior iliac spine in a posterior and inferior direction. If a pop sound occurred, the therapist will proceed to instruct the patient in the ROM exercises. If no pop is produced , the patient will be repositioned and the manipulation will be attempted again (a maximum of two attempts per side was permitted). If no pop sound is produced after the second attempt, proceed to instruct the patient in the pelvic tilt ROM exercises. [23]

Sham manipulation included SM techniques, which consisted of manually applied forces of diminished magnitude, aimed purposely to avoid treatable areas of the spine and to provide minimal likelihood of therapeutic effect. [24] Patients in all treatment groups will be instructed in a pelvic tilt ROM exercise after manipulation (or sham manipulation). Subjects are asked to lie on their back and bend the hips and knees so that their feet are fl at on the surface. Subjects then attempt to flatten their back on the table by slightly “drawing in” their stomach and rotating the hips backward. The motion is to be performed in a pain-free range. Subjects will be instructed to perform 10 repetitions after each manipulation and 10 repetitions 3 times daily on the days they did not attend the session. Pelvic tilt aimed to increase the fl exibility of the lower back and pelvis.

Outcome Measures

Table 1 The primary endpoint was the patient’s self-evaluation of their disability status by use of the Oswestry disability questionnaire after maintained SMT for 10-month period (Table 1) .

Outcome measures included:(1) Subjective Patient-Based Assessments: They are increasingly being used to evaluate the outcome of LBP. [25] Patients completed the following questionnaires at baseline, and at 1-, 4-, 7-, and 10-month periods:

(a) Disease-specific: The Oswestry disability questionnaire was used as a LBP-specific functional assessment. [26] It has been shown to be a valid indicator of disability in patients with LBP. The questionnaire consists of 10 items addressing different aspects of functional capacities. Each item is scored from 0 to 5, with higher values representing greater disability. The total score is multiplied by 2 and expressed as a percentage.

(b) Pain levels were assessed on a visual analog scale (VAS): The VAS consisted of a continuous 100-mm scale. Patients were told that one end of the VAS (0) referred to no pain and the other end (100) referred to the worst pain, and they were asked to mark the level of their pain. VAS is a valid tool to indicate the current intensity of pain. [27]

(c) Generic instruments: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) was used. This is a 36-item general health questionnaire that measures eight dimensions: general health perception, physical function, physical role, bodily pain, social functioning, mental health, emotional role, and vitality. The SF-36 is a valid and reliable instrument widely used to measure generic health status, particularly for monitoring clinical outcomes after medical interventions. [28]

(d) Patient’s global assessment of outcomes: Assessed by asking the patients to compare their current back-related health status with their baseline status, with the following choices: (i) much better; (ii) somewhat better; (iii) mostly the same; (iv) somewhat worse; and (v) much worse. This five level instrument has a score range 1 to 5 (best to worse).(2) Objective Measure: Mobility tests are widely used as an objective measure in patients with LBP. The participants underwent two mobility tests: the modifi ed Schober test [29] and the lateral bending measurement.

Partial blindness of the participants was established, we planned at the study design not to tell the enrolled patients to which treatment group they were randomly assigned, but as the maintained SMT group could be easily discriminated especially in the second phase of the trial, we tried to minimize the risk of bias and overcome this difficulty, by blinding participants to the study hypothesis. Partial information given to our participants consisted of not informing them about the existence of a placebo, participants were aware that different procedures were being compared but not that one treatment was a control. Thus, participants could reasonably expect an improvement regardless of treatment received. To overcome the difficulties in maintaining blinding of participants in the phase of maintenance, participants in the maintained SMT, and control arms did not attend treatment and assessment concurrently and both are not informed about the purpose of the study.

The local ethical committee had approved this work. An informed consent was taken from each patient before enrollment in the study.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for windows version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Continuous data (age and duration of LBP) obtained at baseline were expressed as mean ± SD and compared between each two groups using Student t test. Sex (categorical data) was expressed in number and percent and compared using the χ2 test. The outcome measures were obtained for fi ve different time intervals (baseline, after the first month, and each 3 months in the follow-up periods). The outcome measures between each two groups at the end of the first phase were compared using Student t test. During second phase, we compared the outcome measures among the groups at the end of 4th, 7th, and 10th months. Statistical signifi cance was set at P < 0.05.

Cases with missing values pose an important challenge in this study. Five patients (of the 93 patients who underwent the baseline evaluation) withdraw during the first phase before the start of the sessions. The remainder 88 patients were evaluated at baseline, entered the subsequent sessions and had completed the phase-1 treatment and then revaluated at the end of phase 1. Of these 88 patients, 80 patients were evaluated at the 4th month, 71 patients at 7th month, and 60 patients at the 10th month. Simply discarding these cases , by the method of listwise deletion, could render our analysis inaccurate. Multiple imputation is a statistical technique for handling and analyzing incomplete data sets, that is, data sets for which some entries are missing. The purpose of multiple imputation is to generate possible values for missing values, thus creating several “complete” sets of data. Application of the technique requires three steps: imputation, analysis, and pooling.

In our study, the variables containing the missing data are operated to generate five complete data sets other than the original dataset (imputation step). The five complete data sets are computed and analyzed (analysis step). The results of the analyses are provided and a “pooled” output that estimates what the results would have been if the original dataset had no missing values (pooling step). These pooled results are generally more accurate than those provided by single imputation methods. The pooled data were analyzed using standard procedures (mean, standard error of mean, and the Student t test).

RESULTS

Comparison Among the Three Groups

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

Table 6

Figure 2

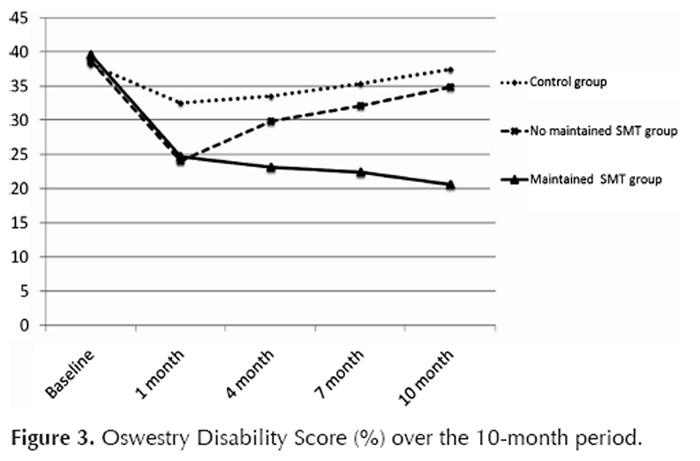

Figure 3 Despite the three groups of patients were similar at baseline evaluation (Tables 1 and 2), patients in the second and third groups experienced significantly lower pain and disability scores compared with the control group after the first phase of treatments, that is, after 1-month period. By the end of second phase of treatment (after 10-month period), patients with maintained SMT had significantly lower pain and disability scores compared with the patients of the nonmaintained SMT group.

Change of VAS Pain Score During the 10-Month Period

The initial phase of treatment yielded a reduction of 12.35 and 13.36 mm in the second and third groups, respectively, whereas it is reduced only by 8.03 mm in the control group on the pain scale (Table 3). At the 4- and 7-month evaluation the mean pain score gradually elevated back toward the pretreatment level in the nonmaintained SMT group. However, pain score in the maintained SMT group continued improving (Tables 4 and 5). By the end of the study, pain score yielded a reduction of 19.26 mm in the maintained SMT group whereas it is returned near to the pretreatment level in the group of patients who discontinued their therapy interventions (Table 6 and Figure 2)

Change of Oswestry Disability Score

A greater difference, however, was seen in disability scores over the duration of the study. By the end of first phase, SMT significantly reduced the disability score in nonmaintained SMT group and maintained SMT when compared with the control group ( P = 0.005 and 0.007, respectively). Analysis of the data after the 10-month period showed that while the disability score of the patients in the nonmaintained SMT group returned back nearly to their pretreatment level, the score was significantly lower in patients who received maintenance SMT compared with the nonmaintained SMT group ( P < 0.001). In the maintained SMT group, the disability score is reduced by an average of 18.98 points lower than baseline level (Table 6 and Figure 3). At the 4- and 7-month evaluation, the mean disability score gradually elevated back toward the pretreatment level in the nonmaintained SMT group. However, disability score in the maintained SMT group continue improving.

Change of SF-36 Score

SF-36 questionnaire showed significantly better outcome after 1-month period for both the second and third groups compared with the control group (Table 3), this continued to improve during the second phase only for the maintained SMT group whereas the nonmaintained SMT group showed progressively reducing SF-36 score (Tables 4 and 5). By the end of the second phase, there was significant difference in the score between the maintained and nonmaintained groups (Table 6).

Change of Spinal Mobility

Measurement of spine flexion and lateral bending yielded increase in their ROM in the maintained SMT group in the first phase and continued to increase in the second phase, whereas in the nonmaintained SMT group the spinal movement increased in the first phase only and decreased to near the pretreatment level by the end of the second phase.

Patient’s Global Assessment of Outcomes

The patient’s global assessment of outcomes was obtained at the end of phase 2 (at the 10-month evaluation) from the 60 patients who had completed the treatment program. Patient’s global assessment scale is significantly better in the maintained SMT compared with nonmaintained SMT and control groups (P = 0.015). On the one hand, in the maintained SMT, 13 (65%) patients reported better outcome (scores 1 and 2) at the end of the treatment program compared with only 7 (35%) and 6 (30%) patients reporting better outcome in the nonmaintained SMT and control groups, respectively. On the other hand, only three (15%) patients in the maintained SMT reported worse outcome (scores 4 and 5) compared to six (30%) and nine (45%) patients in the nonmaintained SMT group and control groups, respectively.

Interestingly, the most common adverse effects reported in this study were local discomfort and tiredness but no serious complications were noted. Most adverse effects were transient and began with 24 hours after treatment and were of mild to moderate severity.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms previous reports showing that SM is an effective modality in chronic nonspecific LBP especially for shortterm effects. [30–37] As the disability and pain scores in our study are significantly reduced in the short-term evaluation — but not in long-term — when compared with the sham manipulation.

The current study also evaluated the effects of maintained SMT in maintaining levels of pain and functional capacity gained after an initial phase of treatment. VAS pain and Oswestry Disability Score remained at the better posttreatment levels only for the group with maintained SMT whereas VAS of pain and Oswestry Disability Score returned to their pretreatment levels for the nonmaintained SMT group.

We designed this trial to deliver SMT in three sessions weekly, then bimonthly in the second phase. One query that had to be investigated is the frequency of the sessions and the intervals between sessions. The observations from previous literature can make us suppose that the unsatisfactory finding during follow-up may be attributed to widely separated manipulation sessions as the trials in which increased numbers of SMT sessions were applied, obtained better outcome in short-term, and continued for sometime after stoppage of treatment, than the trials used less numbers of sessions. For example, on the one hand, studies that applied 12 18 or 10 sessions [38] during 6-week therapy period found that SMT resulted in greater short-term pain relief and disability reduction. On the other hand, studies in which lesser number of sessions over longer treatment period were offered, achieved either mild to slightly moderate benefit on short-term only [39] (eight sessions over 12 weeks) or no benefits over sham treatment (seven sessions over 5 months). [25] However, further researches are needed to find out the optimum frequency and number of the sessions offered to obtain and maintain the best desirable effects.

Only sham-controlled studies in which the control intervention mimicked SM can tell us whether the clinical outcomes of SM are due to specific or nonspecific (e.g. , placebo) effects. [17] So, we enrolled in our study sham SMT in comparison to thrust manipulation and our finding of effectiveness of manipulation versus a sham procedure, agreed with other studies showing that SMT had more short-term pain and disability reduction than sham SMT. [34, 40]

An important issue to be discussed is the state of blindness in the current trial. Partial blindness of the participants was established, by blinding participants to the study hypothesis. Blinding participants to the study hypothesis was proposed either with the use of a sham procedure or when participants and/or health care providers could not be blinded to the treatment they received. [41] Wood [42] showed that lack of blinding yielded exaggerated treatment effect estimates for subjective outcomes but had no effect on objective outcomes. We included in our trial the main domains of patient-based outcomes recommended for evaluating the treatment of spinal disorders [43] and, additionally, we assessed spinal mobility as an objective outcome to support the patient-based assessments.

The disability score difference (>14 points) observed after 10 months in current study between the maintained SMT group and nonmaintained SMT group is statistically significant and clinically important. Fritz and Irrgang [44] showed that a six-point difference in the Oswerstry Questionnaire was the minimal clinically important difference. This six-point difference is the amount of change that distinguishes between patients who have improved and those who remained stable.

The postulated modes of action of SMT include disruption of articular or periarticular adhesions, improve of trunk mobility, [45] relaxation of hypertonic muscle by sudden stretching, release of entrapped synovial folds or plica, attenuation of α-motor neuron activity, enhancement of proprioceptive behavior, and release of β endorphins, thus increase pain threshold. [46] These mechanisms are expected to sustain during maintenance of SMT.

The major limitation of the current study is the missing data from patients who declined to follow-up at different intervals of the study. The method for handling missing data by “listwise deletion” will generally be biased because this method deletes cases that are missing any of the variables involved in the analysis. Moreover, as deletion of incomplete cases discards some of the observed data, complete-case analysis is generally ineffi cient as well, that is, it produces inferences that are less precise than those produced by methods that use all of the observed data. We tried to deal with this situation by using special statistical technique, “multiple imputation” that is applied for handling and analyzing incomplete data sets, that is, data sets for which some entries are missing. Imputation is a more appropriate approach to handling nonresponse on items for several reasons. First, imputation adjusts for observed differences between item nonrespondents and item respondents; such an adjustment is generally not made by complete-case analysis. Second, imputation results in a completed data set, so that the data can be analyzed using standard software packages without discarding any observed values. [47] Experience has repeatedly shown that multiple imputation tends to be quite reasonable method for replacing missing values. It has been shown that by using proper method to create imputations, the resulting inferences will be statistically valid and properly reflect the uncertainty because of missing values. For proper imputation the application of the technique requires three steps: imputation, analysis, and pooling. [48] The SPSS version 17 program used in this study fulfi ll these three requirements. The technique application is mentioned in details under the statistical analysis section.

We delivered maintained therapy to patients in this study for 10 months, which proved efficacy in terms of reducing pain and disability, but whether this gained effect will last and for how long is an issue that should be investigated and discussed in further longitudinal studies with attempts made to prolong the intervals gradually between sessions with more prolonged follow-up after treatment. However, as patients did benefit from the maintenance treatments, we believe that periodic patient visits permit proper evaluation, detection, and early treatment of any emerging problem, thus preventing future episodes of LBP.

Future researches must focus on for how long SMT should be maintained and when to stop it without relapse of pain and how often frequency rate of sessions is helpful. Larger further studies may be carried out to put answers and deduct this debate.

CONCLUSION

SMT is effective for the treatment of chronic nonspecific LBP. To obtain long-term benefit, this study suggests maintenance SM after the initial intensive manipulative.

Key Points

This study demonstrated that SMT is an effective modality in chronic nonspecific

LBP for short-term effects.Application of SMT yielded better results when compared with the sham manipulation.

We suggest that maintained SM is beneficial to patients of chronic nonspecific LBP

particularly those who gain improvement after initial intensive manipulation to

maintain the improved posttreatment pain and disability levels.

References:

Walker BF , Muller R , Grant WD

Low back pain in Australian adults. Health provider utilization and care seeking

J Manip Physiol Ther 2004 ; 27: 327–35 .Waddell G

The clinical course of low back pain

In: Waddell G , ed. The Back Pain Revolution

Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, UK ; 1998 .Bogduk N , McGuirk B

Medical Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: An Evidence-based Approach.

Amsterdam, Netherland: Elsevier , 2002 .Deyo RA , Phillips WR

Low back pain: a primary care challenge .

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996 ; 21: 2826–32 .Carey TS , Garrett JM , Jackman AML

Beyond the good prognosis: examination of an inception cohort of patients with chronic low back pain

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000 ; 25: 1: 115–20 .Maniadakis N , Gray A

The economic burden of back pain in the UK

Pain 2000 ; 84: 95–103 .Kent PM , Keating JL

The epidemiology of low back pain in primary care

Chirop Osteop 2005 ; 13: 13 .Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Kim Burton A, Waddell G.

Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Low Back Pain

in Primary Care: An International Comparison

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001 (Nov 15); 26 (22): 2504–2513Di Fabio RP

Efficacy of manual therapy

Phys Ther 1992 ; 72: 853–64 .Anderson R , Meeker WC , Wirick BE , et al.

A meta-analysis of clinical trials of spinal manipulation

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1992 ; 15: 181–94 .Shekelle PG , Adams AH , Chassin MR , et al.

Spinal manipulation for low-back pain

Ann Intern Med 1992 ; 117: 590–8 .Lee KP , Carlini WG , McCormick GF , et al.

Neurologic complications following chiropractic manipulation: a survey of California neurologists

Neurology 1995 ; 45: 1213–15 .Assendelft WJ , Koes BW , Knipschild PG , et al.

The relationship between methodological quality and conclusions in reviews of spinal manipulation

JAMA 1995 ; 274: 1942–8 .Assendelft WJ , Morton SC , Yu EI , et al.

Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain: a meta-analysis of effectiveness relative to other therapies.

Ann Intern Med 2003 ; 138: 871–81 .Chou R, Huffman LH; American Pain Society.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society/

American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 492–504Flynn T, Fritz J, Whitman J, Wainner R, Magel J, Rendeiro D. et al.

A Clinical Prediction Rule for Classifying Patients with Low Back Pain

who Demonstrate Short-term Improvement with Spinal Manipulation

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002 (Dec 15); 27 (24): 2835–2843Ernst E

Does spinal manipulation have specific treatment effects?

Fam Pract 2000 ; 17: 554–6 .Assendelft WJ , Morton SC , Yu EI , et al.

Spinal manipulative therapy for low-back pain (Cochrane Review)

In: The Cochrane Library , Issue 3

Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd , 2004 .Stig LC , Nilsson O , Leboeuf-Yde C

Recovery pattern of patients treated with chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy for longlasting or recurrent low back pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001 ; 24: 288–91 .Fritz JM , Brennan GP , Leaman H

Does the evidence for spinal manipulation translate into better outcomes in routine clinical care for patients with occupational low back pain?

Spine J 2006 ; 6: 289–95 .Descarreaux M, Blouin JS, Drolet M, Papadimitriou S, Teasdale N:

Efficacy of Preventive Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Low-Back Pain and Related Disabilities:

A Preliminary Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (Oct); 27 (8): 509–514Harvey E , Burton AK , Klaber Moffett J , et al.

Spinal Manipulation for Low-back Pain: A Treatment Package Agreed to by the UK

Chiropractic, Osteopathy and Physiotherapy Professional Associations

Manual Therapy 2003 (Feb); 8 (1): 46–51Cleland JA , Fritz JM , Childs JD , et al.

Comparison of the effectiveness of three manual physical therapy techniques in a subgroup of patients with low back pain who satisfy a clinical prediction rule: study protocol of a randomized clinical trial

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2006 ; 10: 7–11 .Licciardone JC , Stoll ST , Fulda KG , et al.

Osteopathic manipulative treatment for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003 ; 28 ( 13 ): 1355–62 .Deyo RA , Andersson G , Bombardier C , et al.

Outcome measures for studying patients with low back pain

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994 ; 19: 2032S–6S .Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB.

The Oswestry Disability Index

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000 (Nov 15); 25 (22): 2940–2952Olaogun MOB , Adedoyin RA , Ikem IC , et al.

Reliability of rating low back pain with a visual analogue scale and a semantic differential scale .

Physiother Theory Pract 2004 ; 20: 135–42 .Ware JE , Gandek B

Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project

J Clin Epidemiol 1998 ; 51: 903–12 .Macrae IF , Wright V

Measurement of back movement

Ann Rheum Dis 1969 ; 28: 584–9 .van Tulder MW , Koes BW , Bouter LM

Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997 ; 22: 2128–56 .Fritz J , Whitman J , Flynn T , et al.

Factors related to the inability of individuals with low back pain to improve with a spinal manipulation .

Physiol Therap 2004 ; 84: 173–90 .Coxhead CE , Inskip H , Meade TW , et al.

Multicentre trial of physiotherapy in the management of sciatic symptoms

Lancet 1981 ; 1: 1065–8 .Nachemson A , Jonsson E , Englund L , et al.

Neck and Back Pain: The Scientific Evidence of Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment

In: Nachemson AL , Jonsson E , eds.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins , 2000 ; 1–12 .Waagen GN , Haldeman S , Cook G , et al.

Short term trial of chiropractic adjustments for the relief of chronic low back pain

Manual Med 1986 ; 2: 63–7 .Koes BW , Bouter LM , van Mameren H , et al.

The effectiveness of manual therapy, physiotherapy, and treatment by the general practitioner for nonspecific back and neck complaints. A randomized clinical trial

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992 ; 17: 28–35 .Koes BW , Bouter LM , van Mameren H , et al.

Randomized clinical trial of manipulative therapy and physiotherapy for persistent back and neck complaints: results of one year follow-up

BMJ 1992 ; 304: 601–5 .Childs JD , Flynn TW , Fritz JM

A perspective for considering the risks and benefi ts of spinal manipulation in patients with low back pain

Manual Ther 2006 ; 11 ( 4 ): 316–20 .Hemmila HM , Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S , Levoska S , et al.

Longterm effectiveness of bone-setting, light exercise therapy, and physiotherapy for prolonged back pain: a randomized controlled trial .

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2002 ; 25: 99–104 .Underwood M, UK BEAM Trial Team.

United Kingdom Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation (UK BEAM) Randomized Trial:

Effectiveness of Physical Treatments for Back Pain in Primary Care

British Medical Journal 2004 (Dec 11); 329 (7479): 1377–1384Triano JJ, McGregor M, Hondras MA, Brennan PC.

Manipulative Therapy Versus Education Programs in Chronic Low Back Pain

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995 (Apr 15); 20 (8): 948–955Boutron I , Guittet L , Estellat C , et al.

Reporting methods of blinding in randomized trials assessing nonpharmacological treatments .

PLoS Med 2007 ; 4: e61 .Wood L

The association of allocation and blinding with estimated treatment effect varies according to type of outcome: a combined analysis of meta-epidemiological studies

14th Cochrane Colloquium: Bridging the Gaps 2006 23–26 October;

Dublin, Ireland .Bombardier C

Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000 ; 25: 3100–3 .Fritz JM , Irrgang JJ

A comparison of a modified Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire and the Quebec back pain disability scale

Phys Ther 2001 ; 81: 776–88 .Aure, OF, Nilsen, JH, and Vasseljen, O.

Manual Therapy and Exercise Therapy in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Randomized, Controlled Trial With 1-Year Follow-Up

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003 (Mar 15); 28 (6): 525–531Meeker, W., & Haldeman, S. (2002).

Chiropractic: A Profession at the Crossroads of Mainstream and Alternative Medicine

Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (Feb 5); 136 (3): 216–227Pedlow S , Luke JV , Blumberg SJ

Multiple imputation of missing household poverty level values from the national survey of children with special health care needs, 2001, and the National Survey of Children’s Health.

2003,22. 2007. Available at:

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/slaits/mimp01_03.pdf

Accessed July 2011.Rubin DB.

Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys

New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons , 1987

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to MAINTENANCE CARE, WELLNESS AND CHIROPRACTIC

Since 1-25-2011

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |