Opioid Use Among Low Back Pain Patients in

Primary Care: Is Opioid Prescription

Associated with Disability

at 6-month Follow-up?This section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Pain 2013 (Jul); 154 (7): 1038–1044 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Julie Ashworth, Daniel J Green, Kate M Dunn, Kelvin P Jordan

Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre,

Keele University,

Staffordshire, UK.

FROM: Pain 2019 (Dec)

FROM: Cochrane Database 2020 (Apr)

FROM: European Journal of Pain 2017 (Feb)

FROM: American Family Physician 2019 (Mar 15)

FROM: PAIN 2013 (Jul)

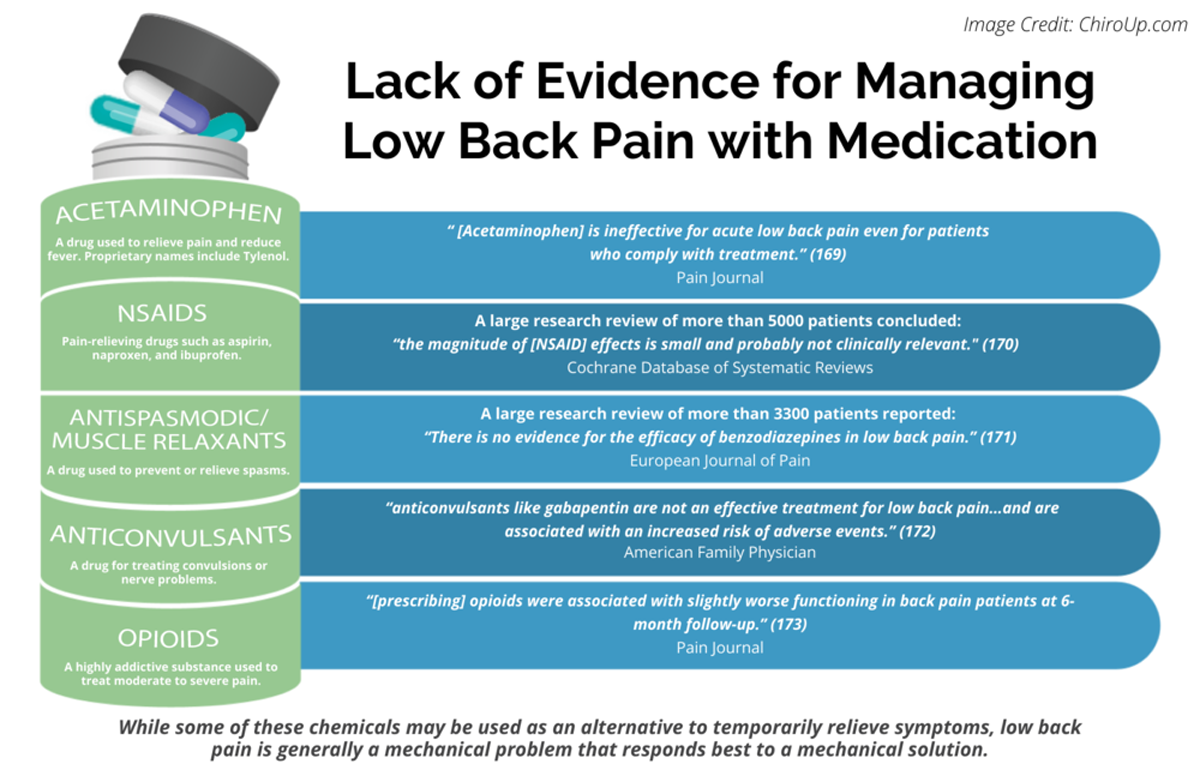

Thanks to ChiroUP 2021 Chiropractic Outcomes SynopsisOpioid prescribing for chronic noncancer pain is increasing, but there is limited knowledge about longer-term outcomes of people receiving opioids for conditions such as back pain. This study aimed to explore the relationship between prescribed opioids and disability among patients consulting in primary care with back pain.

A total of 715 participants from a prospective cohort study, who gave consent for review of medical and prescribing records and completed baseline and 6–month follow-up questionnaires, were included. Opioid prescription data were obtained from electronic prescribing records, and morphine equivalent doses were calculated. The primary outcome was disability (Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire [RMDQ]) at 6–months.

Multivariable linear regression was used to examine the association between opioid prescription at baseline and RMDQ score at 6months. Analyses were adjusted for potential confounders using propensity scores reflecting the probability of opioid prescription given baseline characteristics. In the baseline period, 234 participants (32.7%) were prescribed opioids.

In the final multivariable analysis, opioid prescription at baseline was significantly associated with higher disability at 6-month follow-up (P<.022), but the magnitude of this effect was small, with a mean RMDQ score of 1.18 (95% confidence interval: 0.17 to 2.19) points higher among those prescribed opioids compared to those who were not.

Our findings indicate that even after adjusting for a substantial number of potential confounders, opioids were associated with slightly worse functioning in back pain patients at 6-month follow-up. Further research may help us to understand the mechanisms underlying these findings and inform clinical decisions regarding the usefulness of opioids for back pain.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Opioid prescribing for chronic noncancer pain has increased in recent years [6], and chronic low back pain (LBP) is among the most common nonmalignant disorders associated with prescribed opioid use in primary care. [1, 26] Although opioids are an accepted treatment for LBP, there is limited evidence of their efficacy. [7, 9, 18, 19] The evidence is largely derived from randomized controlled trials with short-term (616 weeks) follow-up, in highly selected populations, and functional outcomes are considered only in a minority of studies. In addition to the uncertainty around efficacy, the epidemiological literature raises concern about potential harms. A Danish study found that opioid use for chronic pain was significantly associated with reporting of severe pain, poor selfrated health, unemployment, higher health care use, and lower self-rated quality of life. [11] In the United States, Kidner et al. [17] reported that patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain who were taking opioids reported higher pain severity, greater disability, and higher levels of depression compared with those who were not. Saunders et al. [29] reported a twofold increase in the fracture risk for older patients prescribed P50 mg daily morphine equivalent dose (MED), and Dunn et al. [10] reported an increasing incidence of accidental overdose with increasing strength of prescribed opioids.

Two previous studies [14, 36] explored the relationship between prescribed opioids and disability in acute LBP and reported an association between early prescription of opioids for LBP and higher long-term disability in U.S. workers’ compensation claimants. A Canadian study [15] looked at the relationship between opioid prescribing and continued disability in a broader range of painful musculoskeletal conditions and also reported that, after adjusting for injury severity, those receiving an early opioid prescription were less likely to return to work. However, this study identified a similar association with receipt of an early prescription for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and muscle relaxants, raising the possibility of confounding by indication. Given the considerable overlap in the factors influencing LBP-related disability and opioid use, there are a number of potential confounders, many of which could not be adjusted for in these studies. Both long-term disability and opioid use have previously been reported to be associated with baseline disability [30, 32], radiculopathy [30, 32], and a number of psychosocial factors. [4, 8, 31] There are conflicting reports about the influence of pain intensity on both disability [5, 8] and opioid use. [12, 31] Furthermore, previous studies in this field are confined to populations of workers in North America, using continued receipt of wage replacement benefits as a surrogate measure of disability, and the generalizability of the findings outside this population is uncertain.

This study sought to assess the relationship between opioid prescribing at baseline and self-reported disability, as measured by the Roland and Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), at 6–month follow-up in a UK population of primary care consulters with LBP. We used a propensity score approach to adjust for a substantial number of important potential confounders in the relationship between opioid use and disability.

Discussion

We observed a significant association between receipt of an opioid prescription in the baseline period and self-reported disability at follow-up, even after adjusting for a large number of potential confounders. However, the increase in mean RMDQ score associated with receipt of an opioid prescription was small and therefore unlikely to be clinically important. [23] Our findings imply, however, that receipt of an opioid prescription at baseline is not associated with improved outcome.

Almost one third (32.7%) of patients with LBP in this study received an opioid prescription within the baseline period, although the majority of patients who received opioids were prescribed only a low dose. The duration of opioid therapy either before or after the baseline period is unknown. Our findings indicate that patients who received an opioid prescription in the baseline period differed significantly in their baseline characteristics from those who were not prescribed opioids and that these differences were more marked for those in the higher dose groups. Those prescribed opioids reported higher pain intensity, including leg pain, and greater disability, and were also more likely to receive medication for comorbid conditions and to report higher distress, greater fear of movement, a greater tendency to catastrophize, and lower self-efficacy.

The proportion of subjects receiving an early opioid prescription for LBP is higher in this study than the 21.2% reported by Webster et al. [36] in the United States and substantially higher than the 7.1% reported by Gross et al. [15] in Canada, although it is similar to that found by Franklin et al. [14] in the United States. It is likely that the variation in reported levels of opioid prescribing reflect differences in study setting, methods, and population.

Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies [14,15,36], which reported higher disability, as measured by continued receipt of wage replacement benefits, in those who received an early opioid prescription for LBP. However, these studies, although they attempted to adjust for some measure of injury severity and basic demographics, were not able to adjust for important potential confounders, including psychosocial variables. Gross et al. [15] found a similar association between prescribed nonopioid analgesics and future disability, and concluded that their findings were likely to be explained by pain severity or other unmeasured confounders. It is perhaps surprising that in our study the association between an opioid prescription at baseline and disability at follow-up remained significant after adjusting for pain intensity and a large number of other potential confounders, whereas no significant association was demonstrated between an NSAID prescription and disability at follow-up, even in the unadjusted analysis. It is difficult to offer a plausible explanation, on purely pharmacological grounds, for why opioids should be associated with greater disability even at very low doses, and although we controlled for a substantial number of known and observed potential confounders, we were not able to adjust for past history of opioid use, smoking history, or the presence of all other painful conditions, and the possibility of residual confounding by unknown factors cannot be excluded.

The major strength of this study lies in combining the use of electronic prescribing records with self-reported measures, allowing us to accurately calculate the morphine equivalent dose and to adjust for a large number of potential confounders, including pain severity, nonopioid analgesic (NSAID) prescription, and psychosocial variables. Other strengths of the study include its prospective design, sample size, and unique primary care setting, which, in the UK health service, is where most new episodes of LBP are managed.

The use of a propensity score approach to adjust for multiple confounders is more efficient than a multivariable regression that includes each variable separately. This leads to less bias in the estimates and more generalizable results. [28] There was loss to follow-up in the original cohort. The 715 participants included in the sample had a slightly higher mean (SD) age than the original study cohort and were slightly more likely to be female, but there were no significant differences in terms of key sociodemographic characteristics, employment status, duration of back pain symptoms, or baseline pain and disability. [13] Given that responders and nonresponders from the original study [13] were almost identical on key baseline characteristics, this offers some reassurance regarding the likelihood of nonresponse bias, although the possibility of unmeasured differences cannot be excluded.

We used electronic databases, which were likely to contain complete data regarding all prescribed opioids. However, opioids can be purchased in low doses without prescription in the UK, and a potential limitation of our study is that it did not capture the use of over-the counter opioid-containing medications. Inequality in the number of subjects in each opioid dose group and in particular the small numbers in the high-dose groups limited our ability to explore the effect of opioid dose on disability, nor could we explore the effect of prescribed opioid use before enrolment in the original study.

Our findings indicate that even after adjusting for a large number of covariates, receipt of an opioid prescription did not improve functional outcome from LBP. Furthermore, our findings suggest that those who are prescribed opioids differ not only in terms of the nature and intensity of reported pain but also in terms of how they respond to that pain, as assessed by self-reported distress, self-efficacy, and coping strategies. It is possible that these and other responses may influence not only disability associated with LBP, but also prescribing behavior of clinicians. [31] It is also possible that patient preference for or against treatment with prescribed opioid analgesics is associated with other differences in patient behavior in the presence of LBP, and that such differences may in turn influence disability.

This study found that opioids were commonly prescribed for patients with LBP, and yet our findings and the previously published literature in this field provide little evidence that this is a useful therapeutic strategy. Although individual randomized controlled trials of opioid analgesics in LBP have demonstrated evidence of short-term pain relief and modest functional improvement in highly selected subjects with LBP, reviews [9, 19] have highlighted the lack of evidence for longer-term pain relief or clinically significant functional improvement. A further recent review [37] concluded that in terms of efficacy in LBP, opioids could not be recommended as a first-line treatment for LBP in view of their side effect profile, potential for tolerance with long-term use, and in the absence of any evidence of superior efficacy compared with NSAIDs. However, it is likely that in recent years, concerns about cardiovascular risk with certain NSAIDs have led to changes in prescribing practice, including increased prescribing of opioid analgesics. [2] It is important that clinicians are aware that prescribing opioids for LBP may not improve patient function. This may encourage closer monitoring of the response to opioid analgesics in terms of both pain and function, providing the opportunity to discontinue where there is no evidence of benefit, and may encourage consideration of alternative therapeutic strategies, including nonpharmacological and psychologically based approaches.

Our findings raise a number of questions for future research. Patients with LBP represent a heterogeneous population, and it is likely that response to opioids and other analgesic medications may differ between subgroups. [37] It is possible that although on average opioids do not improve function in LBP, this conceals a range of responses, including some subjects who obtain functional benefits and others who have a poor response to opioids. An important objective for future studies would be to identify the subgroups of patients who might benefit. Furthermore, identifying the factors that influence a clinician’s decision to prescribe opioids and a patient’s decision to take them might identify potential causal mechanisms for our findings. Pragmatic clinical trials in real-life settings with long-term follow-up are required to inform clinical decisions regarding the management of LBP. The incorporation of subgroup analysis into such trials may further aid the development of clinical recommendations for the management of this heterogeneous patient group.

References:

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to OPIOID EPIDEMIC

Return to FAILED DRUG TRIALS

Since 3-02-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |