Paracetamol Is Ineffective for Acute Low Back Pain

Even for Patients Who Comply with Treatment:

Complier Average Causal Effect Analysis

of a Randomized Controlled TrialThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

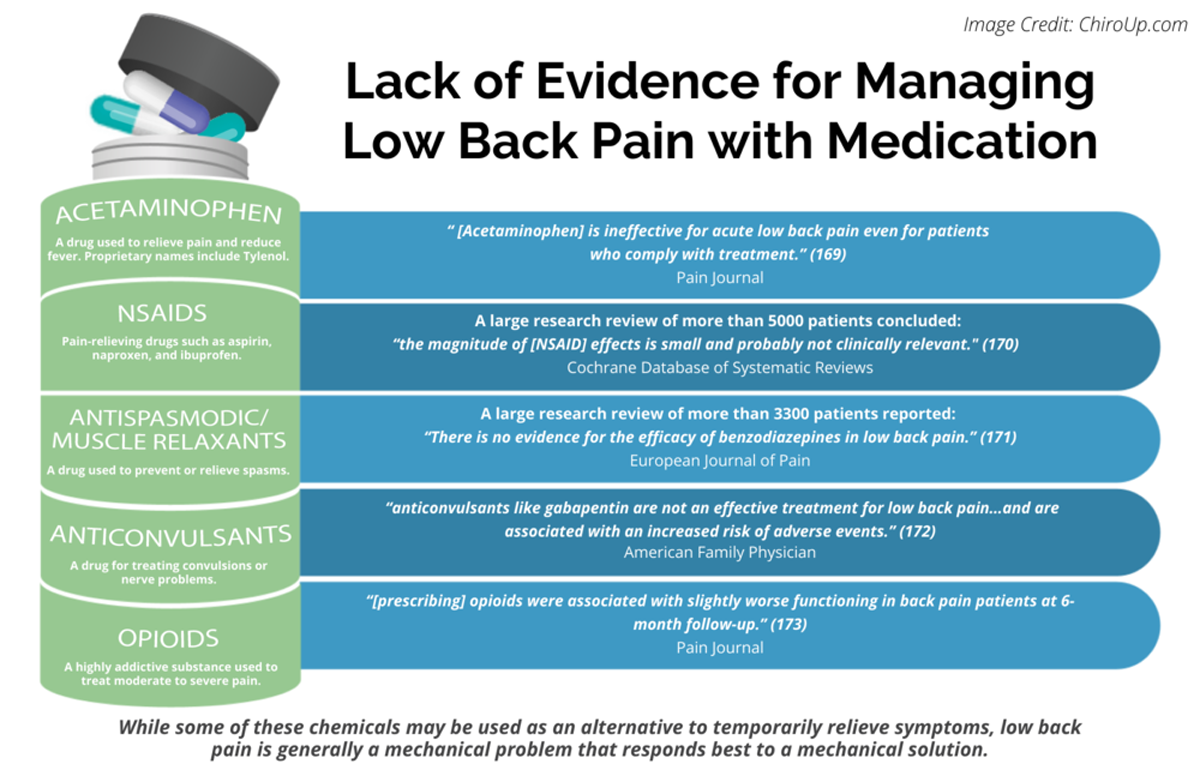

FROM: Pain 2019 (Dec); 160 (12): 2848–2854 ~ FULL TEXT

Marco Schreijenberg, Chung-Wei Christine Lin, Andrew J Mclachlan, Christopher M Williams, Steven J Kamper, Bart W Koes, Christopher G Maher, Laurent Billot

Department of General Practice,

Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam,

Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

FROM: Pain 2019 (Dec)

FROM: Cochrane Database 2020 (Apr)

FROM: European Journal of Pain 2017 (Feb)

FROM: American Family Physician 2019 (Mar 15)

FROM: PAIN 2013 (Jul)

Thanks to ChiroUP 2021 Chiropractic Outcomes SynopsisIn 2014, the Paracetamol for Acute Low Back Pain (PACE) trial demonstrated that paracetamol had no effect compared with placebo in acute low back pain (LBP). However, noncompliance was a potential limitation of this trial.

The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of paracetamol in acute LBP among compliers. Using individual participant data from the PACE trial (ACTN12609000966291), complier average causal effect (CACE), intention-to-treat, and per protocol estimates were calculated for pain intensity (primary), disability, global rating of symptom change, and function (all secondary) after 2 weeks of follow-up.

Compliance was defined as intake of an average of at least 4 of the prescribed 6 tablets of regular paracetamol per day (2660 mg in total) during the first 2 weeks after enrolment. Exploratory analyses using alternative time points and definitions of compliance were conducted.

Mean between-group differences in pain intensity on a 0 to 10 scale using the primary time point and definition of compliance were not clinically relevant (propensity-weighted CACE 0.07 [-0.37 to 0.50] P = 0.76; joint modelling CACE 0.23 [-0.16 to 0.62] P = 0.24; intention-to-treat 0.11 [-0.20 to 0.42] P = 0.49; per protocol 0.29 [-0.07 to 0.65] P = 0.12); results for secondary outcomes and for exploratory analyses were similar.

Paracetamol is ineffective for acute LBP even for patients who comply with treatment. This reinforces the notion that management of acute LBP should focus on providing patients advice and reassurance without the addition of paracetamol.

Keywords: Low back pain, Paracetamol, Acetaminophen, Compliance, Adherence, CACE Analysis

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

The Paracetamol for Acute Low Back Pain (PACE) trial was the first placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigating the efficacy of paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute low back pain (LBP). [29–31] In this RCT, 1,652 people seeking care for LBP were randomized to take paracetamol regularly, paracetamol as needed for pain, or placebo using a blinded double-dummy design. The unexpected result that paracetamol had no effect compared with placebo on pain intensity, time until recovery, disability, and function in acute LBP received worldwide attention in the medical literature and the lay-press. Nonadherence to study medication was identified as a potential limitation in the original publication of the PACE results as well as in a number of commentaries discussing the impact of the trial [4, 16, 17, 31]; in a descriptive analysis of nonadherence in PACE, 70% of patients were found to be nonadherent over the 4-week treatment period, and overall adherence to guideline-recommended care for acute LBP was described as “poor.” [4] In RCTs, noncompliance has always been an issue and may even influence their results. [21] However, the question as to whether there is benefit of an intervention in participants who adequately adhere to treatment is difficult to answer using conventional techniques used in the analysis of RCTs (ie, intention-to-treat [ITT] analysis and per protocol analysis).

Complier average causal effect (CACE) analysis involves comparing participants who were randomized to the intervention and complied, to participants from the control group who would have complied to the intervention had they been randomized to the intervention (so-called “would be compliers”). As participants in the control group are never offered the active treatment in reality, there are no observed data in the control group for adherence to active treatment. Complier average causal effect analysis is therefore essentially a missing data problem. Complier average causal effect analyses have been used to assess the efficacy among compliers of intervention programs in substance abuse, behavioral interventions, and a multifactorial intervention in physiotherapy. [1, 2, 8–11, 18, 24, 26] In the field of LBP, CACE analysis has been used to assess the influence of noncompliance on effectiveness of a cognitive behavioral intervention. [15]

This analysis aims to investigate the efficacy of paracetamol in acute LBP among participants who complied with regular paracetamol treatment in the PACE trial using a CACE analysis, to address the uncertainty that compliance may have influenced drug efficacy. [1, 26] In addition, we conducted ITT analysis and per protocol analysis to compare with the CACE analysis.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of the PACE trial, we found that paracetamol had no clinically meaningful effect when compared with placebo on pain intensity, disability, global rating of symptom change, and function in people with acute LBP who complied with regular paracetamol.

The CACE analysis technique produces robust estimates of efficacy amongst compliers; furthermore, we applied 2 distinct methods to estimate CACEs, which serve as each other’s sensitivity analysis. [26] The credibility of our findings is supported by the fact that no large differences exist between these 2 estimation techniques. [26]Data used in this analysis were collected in a large and well-conducted RCT. [23, 31]

The CACE analysis technique has 2 main weaknesses. First, no universally accepted definition of compliance to paracetamol for LBP exists. Using our main definition of compliance, 72% of participants in the regular paracetamol group were classified as compliers. We explored stricter definitions of compliance and found results consistent with the primary analysis; however, as the percentage of compliers was lower using these definitions, CACE estimates using these definitions are less robust. Second, CACE estimates were based on patient-reported compliance filled out in paper drug diaries, which may not have perfectly represented actual consumption of tablets. However, counts of returned medicines and results from the brief adherence rating scale were consistent with patient-reported compliance. [31]

The findings of this secondary analysis should be placed in context of the original analysis of the PACE trial, which is still the only RCT that has assessed the efficacy of paracetamol for acute LBP and is considered to be the best available evidence. [23] As mentioned in the introduction, noncompliance to study medication was considered a potential limitation of the PACE results. [4, 16, 17, 31] The results of this analysis suggest this is not the case and thus support the conclusion from the original analysis of the PACE trial that paracetamol is ineffective for acute LBP when compared with placebo. It is important to note that CACE analysis is a technique that accounts for a very specific participant group, namely those who comply with treatment. Although this analysis technique may be useful in trials where noncompliance is an issue, results of the ITT analysis remain the most relevant to clinical practice.

After a lack of efficacy of paracetamol for acute LBP was demonstrated by the PACE trial, paracetamol was no longer recommended as first choice analgesic in 4 of 8 recently published national clinical practice guidelines. [3, 6, 22, 28] However, other recent guidelines still endorse the prescription of paracetamol for acute LBP. [5, 12, 20, 25] One possible justification was that paracetamol may be effective in those who comply with the dosing regimen. Our CACE analyses have demonstrated that the efficacy of paracetamol is unlikely to change even in patients with total compliance to the regular regimen, reinforcing that management of acute LBP should focus on providing patients advice and reassurance without the addition of paracetamol.

In conclusion, paracetamol is not more effective than placebo for acute LBP in compliers of the treatment regimen. Complier average causal effect analyses using different cut points showed that paracetamol had no effect on pain intensity and secondary outcomes when compared with placebo for participants that complied to regular paracetamol in the PACE trial. These results support the original findings of the PACE trial.

Conflict of interest statement

The University of Sydney School of Pharmacy receives funding from GlaxoSmithKline for a postgraduate research scholarship supervised by A.J. Mclachlan. C.G. Maher has received funding to review teaching materials prepared by GlaxoSmithKline. C.-W. Christine Lin, A.J. Mclachlan, C.M. Williams, and C.G. Maher were investigators of the PACE trial. C.-W. Christine Lin, C.G. Maher, A.J. Mclachlan, B.W. Koes, and L. Billot received in-kind support from Pfizer Australia for an investigator-initiated trial of pregabalin vs placebo in sciatica, but retained full autonomy of the trial. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of this research, the clinicians involved in participant recruitment, and the research support staff involved in site monitoring, data collection, data management, and data analysis. The authors thank Severine Bompoint for her assistance in the creation of the forest plots presented in this article.

The PACE trial was an investigator-initiated study funded by a project grant from National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. GlaxoSmithKline Australia provided subsequent supplementary funding and the paracetamol and matched placebo, but the investigators retained full autonomy over the design, conduct, analysis, and reporting of the trial.

C.G. Maher is supported by a Principal Research Fellowship from Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1103022).

C.-W. Christine Lin is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (APP1061400).

C.M. Williams is supported by an Early Career Research Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (APP1113272).

S.J. Kamper is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (APP1127932).

This secondary analysis of the PACE data has been supported by a program grant of the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and by the Foundation “De Drie Lichten” in The Netherlands.

Author contributions: C.-W. Christine Lin, A.J. Mclachlan, C.M. Williams, and C.G. Maher made substantial intellectual contributions to the development of the original study protocol, data collection, statistical analysis and drafting the original results of the PACE trial.

M. Schreijenberg, C.-W. Christine Lin, A.J. Mclachlan, C.M. Williams, S.J. Kamper, B.W. Koes, C.G. Maher, and L. Billot all made substantial intellectual contributions to the development of the CACE analysis protocol.

M. Schreijenberg and L. Billot had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. M. Schreijenberg drafted the manuscript, which was revised by C.-W.

Christine Lin, A.J. Mclachlan, C.M. Williams, S.J. Kamper, B.W. Koes, C.G. Maher, and L. Billot. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References:

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to FAILED DRUG TRIALS

Since 6-02-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |