Full-Coverage Chiropractic in Medicare: A Proposal to

Eliminate Inequities, Improve Outcomes, and Reduce

Health Disparities Without Increasing Overall Program CostsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Chiropractic Humanities 2020 (Dec 7); 27: 29–36 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Robert A.Leach, DC, MS

Food Science,

Nutrition and Health Promotion,

Mississippi State University,

Starkville, Mississippi

Davis ~ J Am Board Fam Med 2015Objective: The purpose of this article is to discuss evidence that supports the resolution of inequities for Medicare beneficiaries who receive chiropractic care.

Discussion: Medicare covers necessary examinations, imaging, exercise instruction, and treatments for beneficiaries with back pain when provided by medical doctors, osteopaths, and their associated support staff such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical nurse specialists, and physical therapists. However, if the same patient with back pain presents to a chiropractor, then the only service that is covered by Medicare is manipulation of the spine. Current evidence does not support this inequity in Medicare beneficiary service coverage. There is no evidence to show an increase in serious risks associated with chiropractic treatment of neck or back pain in Medicare beneficiaries. Chiropractors support national public health goals and endorse safe, evidence-based practices.

Chiropractic care for Medicare beneficiaries has been associated with enhanced clinical outcomes such as faster recovery, fewer back surgeries a year later, reduced opioid-associated disability, fewer traumatic injuries and falls, and slower declines in activities of daily living and disability over time. Further evidence points to lower costs, fewer medical physician visits for low back pain, less opioid-related expense, and less back-surgery expense with chiropractic utilization. Use is lower among vulnerable populations: seniors, lower income women, and black and Hispanic beneficiaries who may be most affected by current inequities associated with the limited coverage. In this era of evidence-based and patient-centered care, beneficiaries who receive chiropractic care are very satisfied with the care they receive.

Conclusion: The current evidence suggests a need for change in US policy toward chiropractic in Medicare and support for HR 3654. Ending inequities by providing patients full coverage for chiropractic services has the potential to enhance care outcomes and reduce health disparities without increasing program costs.

There are more articles like this @ our:

Keywords: Chiropractic; Healthcare Disparities; Medicare

From the FULL TEXT Article:

INTRODUCTION

Currently, Medicare has limited coverage for chiropractic services. Medicare Part B (medical insurance) covers manual manipulation of the spine if medically necessary to correct a subluxation when provided by a chiropractor or other qualified provider. Medicare does not cover other services or tests ordered by a chiropractor, including xrays, massage therapy, and acupuncture. [1] Of all health care provider types whose services are covered in the Medicare program for treatment of spine pain, only patients of chiropractors have no coverage for the exams, radiographs, and necessary therapeutic procedures such as exercise instruction and lifestyle advice that are critical to attaining longterm improvement and preventing recurrence. [1–6]

In 1973, when chiropractic was added as a Medicare Part B (outpatient) benefit, it was primarily in response to a public outcry to include the popular treatment in the federal program for seniors and persons with disabilities. [1] The final compromise of chiropractic coverage that was worked out by the House and Senate purportedly was influenced by the American Medical Association. The result was that chiropractors were required to take a radiograph (ie, a diagnostic imaging study that uses x-rays to create an image) prior to being allowed to give chiropractic care. Although the radiograph requirement has since been removed, radiographs taken by chiropractors have never been a covered service. Experts believe this language was an attempt by the American Medical Association to create a barrier for patients seeking chiropractic care. [1, 7, 8]

The debate over coverage of chiropractic has continued, with the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services examining chiropractors billing for follow-up care. [8] According to the Department of Health and Human Services, “Medicare covers chiropractic services for active/corrective treatment for subluxation of the spine but does not cover maintenance therapy.” [10] Maintenance care has been traditionally offered to patients who see clinical gains after initial services are rendered. However, without evidence to support the use of preventive maintenance care by chiropractors, the department concluded that it was not medically necessary, despite continued popular use of the service by patients of chiropractors. [10] To help address these questions, Congress authorized a Medicare demonstration project whereby beneficiaries in certain areas within 5 US states were able to access the full range of chiropractic services allowed. [11]

Although findings from the demonstration pointed to an overall slight increase in program costs, the demonstration treated chiropractic as an add-on service (ie, chiropractic was not treated as a service that can stand alone, but rather costs were expected to accrue in addition to all other physician, diagnostic imaging, and surgical expenses covered by Medicare). Unfortunately, the demonstration did not take into account such offsets as possible reduced orders for advanced diagnostic imaging or back surgeries, or reduced physician visits that may have been incurred had patients not gone to a chiropractor. [11] The program also did not address whether clinical outcomes improved when beneficiaries were able to fully access chiropractors for the full range of services they normally provide. [11, 12]

There are still questions underlying chiropractic care within Medicare that need to be explored. The purpose of this article is to discuss an evidence-based rationale for why equity is needed for Medicare beneficiaries who seek chiropractic treatment and for permitting full coverage for services, as would be expected when seeking care for back pain from any other Medicare health care provider in the United States. I discuss whether full coverage for chiropractic might help to reduce health disparities by improving access to chiropractic for the vulnerable populations presently underserved by chiropractors, including those in lower income, elderly, and racially diverse groups.

DISCUSSION

Table 1 Comparing types of providers whose services are covered in the Medicare program for treatment of spine pain, only patients of chiropractors have no coverage for the exams, radiographs, and necessary therapeutic procedures such as exercise instruction and lifestyle advice that are critical to attaining long-term improvement and preventing recurrence. Table 1 shows services related to back pain covered by Medicare, by provider type. [1–6] Regarding reducing inequities for patients who go to chiropractors, an important concern for policy makers and taxpayers is cost. The answer may be complex, especially if it involves looking at divergent variables such as safety, actual costs (what patients spend for an episode of care compared to another provider), possible offset savings (fewer physician visits, less expensive advanced imaging procedures, fewer back surgeries, or less opioid-related disability and expense), and the effectiveness of chiropractic care.

If physical therapists and medical doctors were able to provide more effective care, then prohibitions against coverage for chiropractic services might be justifiable, because some goals espoused by the Affordable Care Act advocate for enhanced coverage of evidence-based treatments. [13] Another issue is whether chiropractic care is cost effective — even if it is equally or more effective compared to other care, what is the cost of its addition? In attempting to address these issues, information may be found in recent large-scale epidemiologic inquiries involving the entire US Medicare database, in addition to multiple other studies from the past few years that have dealt with these and additional questions raised by the Medicare demonstration project and several that may even shed a different light on the Office of the Inspector General reports.

Chiropractors Engage in Health Promotion

Detractors of chiropractic expansion have argued that chiropractic is dangerous [14, 15] and that chiropractors refrain from endorsing and advocating for public health preventive measures. [16] In response to these arguments, 2 large-scale epidemiologic studies in the United States have addressed the issue of association of chiropractic and stroke. An earlier epidemiologic study had looked at more than 100 million person-years of data from 1993 to 2002 and found that there was no greater association of vertebral artery stroke for patients seeing a chiropractor than those seeing a medical doctor. [17] It also found that for older patients, stroke was correlated with a prior recent visit to a medical doctor. More recently in the United States, a report of a total of 1,829 vertebral artery strokes reported among commercial and Medicare Advantage patients from 2011 to 2013 showed an association between strokes and visits to primary medical care but not chiropractor providers. [18]

It concluded that the positive association between primary medical visits and stroke was likely due to patients seeking care for the headache and neck pain associated with these lesions. [17, 18] A second study reported on a sample of Medicare Part B beneficiaries aged 66 to 99 years, including 1.1 million claims where patients complained of neck pain. [19] Differences in risk for subsequent stroke of any type, not merely allegedly manipulation-induced vertebral artery strokes, between patients who saw a chiropractor or a primary care physician were not clinically significant. The authors concluded that associations reported in case reports were likely due to patients going to a chiropractor while having symptoms of a stroke in progress. Another inquiry addressed the relative safety of chiropractic care, reporting that the risk of traumatic injury for all Medicare Part B beneficiaries after presenting with a neuromusculoskeletal complaint was greater for those seen by a primary care doctor (153 incidents per 100,000) than for those seen by a chiropractor (40 incidents per 100,000). [20] And where previously some medical doctors offered individual reports of alleged serious spine injuries such as herniated discs after spinal manipulation, [21, 22] a recent study of 100 million person-years of data revealed no more emergency treatments of herniated discs after initial presentation to chiropractors than after initial presentation to medical doctors. [23]

Another multicenter study found that benefits outweigh risks for patients with serious neck pain. [24] A large medical trial suggested that there may not be a long-term benefit of back surgery, and that surgery not only is expensive but may have more risk compared to conservative care. [25] Hence, for Medicare Part B beneficiaries, safety would likely be enhanced by adding chiropractic care rather than reduced by it. In the past decade there has been growing evidence to support the contention that chiropractors are advocating for evidence-based public health policy. There has been discussion within the chiropractic community regarding public health that aligns with US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention initiatives and goals. [26] There is evidence for strong support among chiropractors for goals espoused by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from recommendations on nutrition to exercise and staying active, and from preventing falls to reducing substance abuse and offering counseling advice and other goals. [26, 27] Based on current evidence, chiropractors have developed and updated guidelines for best practices including radiology, care for patients with neck and back pain, and care for older adults, all of which emphasize safe, effective, and patient-centered care. [28–34]

Chiropractic Care Enhances Clinical Outcomes

Some have argued over research regarding the effectiveness of chiropractic compared to physical therapy or usual medical care. One study was commissioned to determine whether chiropractic should be included in the British national health insurance program. The lead investigator argued that the statistically significant improvement after chiropractic (compared to Maitland manipulation/mobilization as used by physical therapists) was clinically meaningful and that lowered disability with chiropractic care persisted after a 3 year follow-up. [35–39]

The United States Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research argued that spinal manipulation was “safe and effective” for acute back pain, and that commonly used physical therapy procedures, other than self-care and exercise advice, and even back surgery, were not effective for the majority of patients with low back problems. [40] Similar conclusions were reached in a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, which reported that there was moderate-quality evidence that both manipulation (a treatment used by chiropractors) and mobilization (a treatment used by physical therapists) are likely to reduce pain and improve function in patients with chronic back pain.

Spinal manipulation appeared to produce a larger effect, and the researchers noted that both treatments appeared safe, concluding that programs using a variety of treatments may be a promising option. [41] Focusing on treatment for Medicare beneficiaries seeing a chiropractor, researchers analyzed 12,170 person-years of data and found that chiropractor-treated beneficiaries had slower decline in activities of daily living, disability, lifting, stooping, walking, self-rated health, and worsening health after 1 year, compared with patients receiving usual medical care. [42] The authors reported that a year later, they also found higher satisfaction ratings for chiropractic care for back pain.

Although many studies have found consistently higher satisfaction with chiropractic for treatment of back pain, one study has also suggested that patients receiving chiropractic manipulations for neck pain were similarly more satisfied with their general care than patients randomized to home exercise and advice or to medications. [43] A study that sampled midlife and older US adults found that many had used chiropractic health approaches (chiropractic, herbs, massage, and yoga) for either acute care or wellness, with wellness and combined users reporting benefits compared with treatment only for acute pain. [44]

And there are additional questions surrounding the Office of the Inspector General reports of chiropractors billing for maintenance care (sometimes called extended maintenance or preventive or wellness care). [45] Typically, chiropractors stop billing Medicare for extended maintenance care following the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services guidance to have patients sign an Advance Beneficiary Notice of Noncoverage form acknowledging that Medicare does not pay for this service. However, there are some patients who opt for this chiropractic service and pay for it out of pocket.

It has been reported the that benefits of extended chiropractic care (ie, preventive maintenance) include reduced back disability a year later compared to patients receiving only initial chiropractic or no chiropractic. [46] Further studies by physical therapists and chiropractors have shown that patients have less time lost from work and less disability when they receive spinal mobilization less frequently but on an extended basis after their initial care is completed. [45–48]

Chiropractic Services Would Not Increase Overall Medicare Program Costs

For decades, various state worker’s compensation departments or insurance carriers reviewed and published chiropractor- related expenses, and almost all found chiropractic services to be cost-effective, even in lowering unemployment compensation payouts. [49–52] More recently, a number of studies have looked at actual costs of chiropractic care. The Congressional Budget Office has traditionally scored chiropractic as an add-on that does not save costs elsewhere, even looking for ways to further restrict the limited coverage provided, such as by use of preauthorization for spinal mobilization. [53] The large 5–state Medicare demonstration project allowed for full coverage of regular chiropractic services and yielded slightly increased costs for the Medicare program. [12]

Yet further analysis revealed that a small number of Chicago chiropractors actually accounted for the increase; some have argued that a simple cap on numbers of visits, or auditing of records of those doctors regularly exceeding visit norms, could eliminate this issue. [3, 11, 12] In contrast with this narrow view that full coverage chiropractic is only an add-on, a number of studies have begun looking at possible savings as a result of Medicare beneficiaries seeing chiropractors, termed “offsets.” For example, between the years 2006 and 2012, among 72,326 of the most multiply comorbid Medicare beneficiaries presenting with low back pain, those who received only chiropractic treatment had lower overall costs of care, shorter episodes, and lower incidence of back surgery a year later compared with those who sought care from a physical therapist and/or medical doctor. [54]

The possibility of chiropractic care helping ease the burden of spine surgery alone could be a significant cost savings to the Medicare program. Other studies similarly point to other savings or offsets that may be associated with chiropractic care. For example, several studies suggest lower opioid use among Medicare beneficiaries, military personnel, and mixed populations when chiropractic is more readily available, such as a study based on 2011 data which showed that a higher per capita supply of doctors of chiropractic and Medicare spending on chiropractic adjustments were inversely associated with younger disabled Medicare beneficiaries obtaining an opioid prescription. [55]

And a study of 142,539 Army veterans previously deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan found reduced opioid and drug addiction in addition to less suicidal ideation when chiropractic or other bodywork therapists provided care. [56] In addition, this year a study of 101,221 subjects aged 18–84 years who were enrolled in a health plan and who reported visits to a primary care provider or a chiropractor for spinal pain reported that recipients of chiropractic care had half the likelihood of filling an opioid prescription, and even lower risk if they saw a chiropractor within the first 30 days of diagnosis. [57]

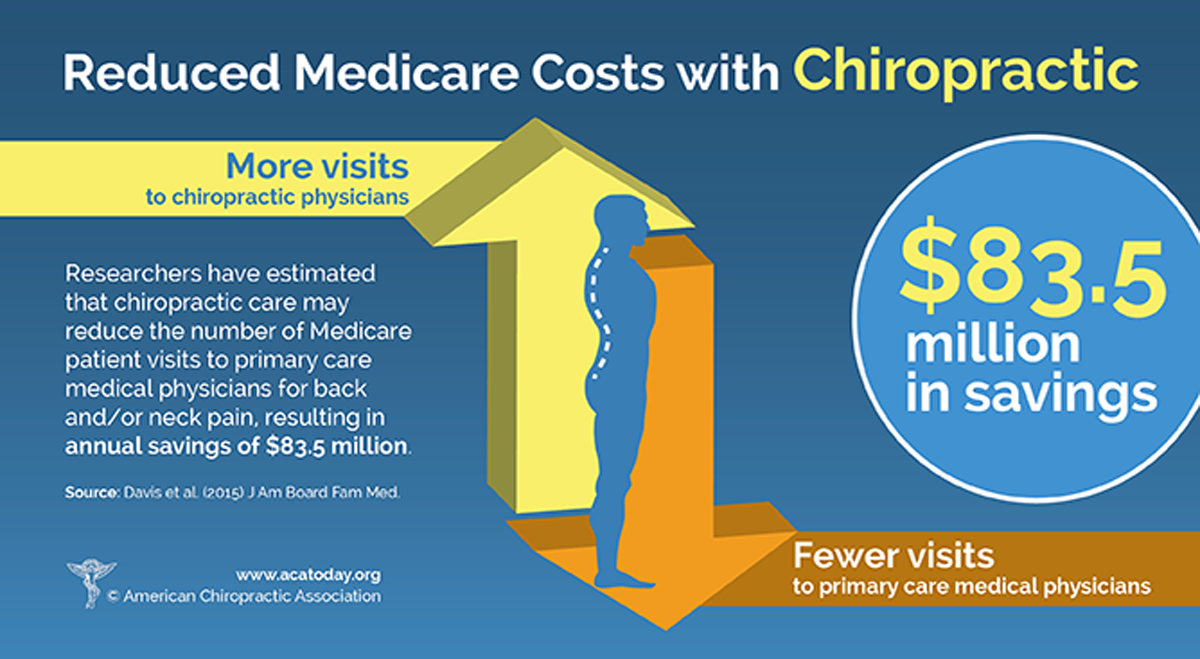

A large study of Medicare beneficiaries found that as the supply of chiropractors increased in a geographic area, visits to primary care physicians for back and/or neck pain decreased. [58] The study, reported by medical doctors and scientists, found that of 17.7 million Medicare beneficiaries enrolled from 2010 to 2011, overall, in areas with more chiropractors, 0.37 million fewer physician visits were made by beneficiaries, at a projected cost savings to Medicare of $83.5 million. [58] And unlike the congressionally funded demonstration project, which included a high-fee zone in Chicago that skewed the findings, [11] research from a nationally representative sample of over 5.4 million Medicare Part B claims affirmed that chiropractor visit fees decreased 18% over the period, whereas physician visit fees increased 10%. [59]

Adding further support to these observations, researchers reported that of 84,679 older adults enrolled in Medicare with a spine condition who relocated once between 2010 and 2014, there was a negative dose response for spine-related spending on medical evaluation and management as well as diagnostic imaging and testing (mean differences of $20 and $40, respectively) among those with greater access to chiropractors. [60] The possibility that full inclusion of a relatively low-fee service like chiropractic may lower overall program costs while at the same time enhancing clinical outcomes, lowering opioid addiction, lowering primary care provider visits for back pain, reducing advanced imaging costs, and perhaps reducing surgeries would seem to be compelling evidence for adoption of full-coverage chiropractic as a cost efficiency for the Medicare program.

Chiropractors May Help Reduce Health Disparities

An important issue addressed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is that health disparities should be reduced among groups, races, ages, and sexes. In this case, in light of the growing evidence, the question arises as to whether federal policy regarding chiropractic over the past half century may have unwittingly contributed to health disparities. [27] In a study of 7,502 beneficiaries who used chiropractic, 72% were white, 12% Asian, only 1% black, and 14% Hispanic, with much higher utilization in areas with a large distribution of chiropractors. [61] A free chiropractic clinic in Buffalo, New York, saw predominantly impoverished, female, African American patients with chronic back pain. [62] Data published by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that in the past year, 10.3% of Americans used chiropractic, including 12.7% of white citizens but only 5.5% of black and only 6.6% of Hispanic citizens; further, 11.4% of older adults (aged 45–64 years) used chiropractic, but that dipped to 9.5% for those aged 65 years and above. The findings that female, black, Hispanic, and senior adults are underserved by chiropractic have been observed in other research, [63] and underscore the possibility that the present Medicare policy may act as what economists refer to as a barrier to entry for some of the most vulnerable populations in the United States. [64]

Whether beneficiaries are attended for back pain by physicians or chiropractors, a preliminary physical evaluation must be performed to establish the medical necessity for subsequent treatment. However, beneficiaries who go to their medical doctor find that physical exams and radiographs are paid for as needed, whereas beneficiaries who call to check what Medicare pays for at the chiropractor’s office find out these services are not covered. In the 1970s, chiropractic and organized medicine were in a battle. [65]

However, since that time, interprofessional collaboration and integrative care have changed the health care landscape considerably, with a nationally representative sample of physicians reporting that among complementary health approaches, referrals to chiropractic account for 27%, second only to massage. [66] Professional medical guidelines for back pain encourage physicians to refer for spinal mobilization, yoga, and other complementary and alternative medicine therapies before considering opioid prescription for back pain. [66] It appears that there is a support for eliminating the inequities currently faced by Medicare beneficiaries seeking chiropractic care. The provision of full coverage for chiropractic services may improve access to Medicare for the vulnerable populations for whom it is most needed, helping to reduce disparities in access to health care. [3, 67]

CALL TO ACTION

The House of Representatives is considering a resolution from Representatives Brian Higgins (NY-D) and Tom Reed (NY-R), who introduced HR 3654 on July 9, 2019, in the 116th Congress, aiming to rectify the nearly 5–decade issue of unequal coverage for Medicare beneficiaries with back pain who seek chiropractic care. [68] As of this writing in September 2020, the bill has 82 cosponsors (43 Republican, 39 Democratic), and summarizes its purpose as “[amending] amend Title XVIII of the Social Security Act to provide Medicare coverage for all physicians’ services furnished by doctors of chiropractic within the scope of their license, and for other purposes.” [68]

Enactment of this bill into law would have the immediate effect of relieving the inequities and their manifestations as briefly explored in this article. To support passage of this legislation, the chiropractic community — including patients who benefit from the care — should engage all stakeholders in academia, the press, legislatures, and regulatory bodies. Advocacy and messaging should include discussions of less opioid use, reduced back surgeries and costs, and greater patient satisfaction associated with chiropractic.

Publications should also advocate for research on full integration of chiropractors within the health care community. Research is needed to determine those who serve as point of entry for most Medicare patients with back pain (eg, physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, osteopaths, chiropractors). Research is also needed to determine the relative costs to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services of the back pain treated by various provider types—and not merely the immediate costs associated with various providers, but global costs including subsequent radiographs, therapies, and referrals for advanced imaging, injections, and surgeries over time, balanced against long-term outcomes. Until such questions are investigated, full inclusion of inexpensive conservative chiropractic care within Medicare would seem to be a pragmatic first step for our government, especially given the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national goals of reducing health disparities.

I argue that there is room for all treatments for back pain, especially because there is not at present any single universal cure, whether manual, pharmaceutical, surgical, psychosocial, or behavioral. In this view, practitioners should work together to solve what the World Health Organization has termed the leading cause of musculoskeletal disability, which is also the largest single category of disability worldwide. [67, 69] For integrative and collaborative care to work effectively, all players should be able to refer, interact, follow evidence-based guidelines, and consider patient preferences and viewpoints. When patients are artificially constrained from receiving treatment for back pain that they themselves highly rate as effective, no one benefits: not government or payors, not practitioners who would otherwise collaborate on case management, and certainly not patients with back pain, who, owing to lack of full coverage at the chiropractor’s office, are financially incentivized to seek care elsewhere that may not be evidence-based.

Vulnerable patients who most need chiropractic services, such as those who are older, poor, female, and/or members of racial or ethnic minorities—who often are involved in physical and manual labor—should not be the citizens least likely to receive what scientists have concluded is a safe, inexpensive, and effective single treatment for back pain beyond self-care and exercise. It is time to end discrimination against Medicare beneficiaries who seek chiropractic care. It is time for Medicare to pay for the required screening exams, radiographs when indicated, guidance and tips for healthy eating and lifestyle choices, help with activities of daily living, and exercise counseling and instruction—the full range of services at a chiropractor’s office—so that our senior citizens and vulnerable populations can experience enhanced clinical outcomes without increasing Medicare program costs.

References:

Young KJ.

Politics ahead of patients: the battle between medical and chiropractic professional associations

over the inclusion of chiropractic in the American Medicare system.

Can Bull Med Hist. 2019;36(2):381-412.Wardwell WI.

Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession.

St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1992.Whedon JM, Goertz CM, Lurie JD, Stason WB.

Beyond Spinal Manipulation: Should Medicare Expand Coverage

for Chiropractic Services? A Review and Commentary

on the Challenges for Policy Makers

Journal of Chiropractic Humanities 2013 (Aug 28); 20 (1): 9–18Doctor & other health care provider services. Available at:

https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/doctor-other-healthcare- provider-services

Accessed September 6, 2020.Keil AP, Baranyi B, Mehta S, Maurer A.

Ordering of diagnostic imaging by physical therapists: a 5-year retrospective practice analysis.

Phys Ther. 2019;99(8):1020-1026.US Department of Health and Human Services.

Medicare Carriers Manual Part 3 Claims Process, Change Request 1279 (2001). Available at:

https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/Down loads/R1734B3.pdf

Accessed September 6, 2020.Wardwell WI.

Differential evolution of the osteopathic and chiropractic professions in the United States.

Perspect Biol Med. 1994;37(4):595-608.Wardwell WI.

The sixteen major events in chiropractic history.

Chiropr Hist. 1996;16(1):66-71.Levinson DR.

Hundreds of Millions in Medicare Payments for Chiropractic Services Did Not Comply With Medicare Requirements.

Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services

Office of the Inspector General; 2016. Report A-09-14-02033 .Inspector General.

Medicare spends hundreds of millions on medically unnecessary chiropractic services.

Mo Med. 2016;113(6):443.Stason WB, Ritter GA, Martin T, Prottas J, Tompkins C, Shepard DS.

Effects of expanded coverage for chiropractic services on Medicare costs in a CMS demonstration.

PLoS One. 2016;11:(2) e0147959.Weeks WB, Whedon JM, Toler A, Goertz CM.

Medicare’s demonstration of expanded coverage for chiropractic services:

limitations of the demonstration and an alternative direct cost estimate.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013;36(8):468-481.Medicare program; payment policies under the physician fee schedule

and other revisions to Part B for CY 2011.

Final rule with comment period.

Fed Regist. 2010;75(228):73169-73860.Chen WL, Chern CH, Wu YL, Lee CH.

Vertebral artery dissection and cerebellar infarction following chiropractic manipulation.

Emerg Med J. 2006;23(1):e1.Gouveia LO, Castanho P, Ferreira JJ.

Safety of chiropractic interventions: a systematic review.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(11):E405-E413.Johnson C, Baird R, Dougherty PE, et al.

Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(6):397-410.Cassidy JD, Boyle E, Cote P, et al.

Risk of Vertebrobasilar Stroke and Chiropractic Care: Results of

a Population-based Case-control and Case-crossover Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008 (Feb 15); 33 (4 Suppl): S176–183Kosloff, TM, Elton, D, Tao, J, and Bannister, WM.

Chiropractic Care and the Risk of Vertebrobasilar Stroke:

Results of a Case-control Study in U.S. Commercial

and Medicare Advantage Populations

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2015 (Jun 16); 23: 19Whedon, JM, Song, Y, Mackenzie, TA, Phillips, RB, Lukovits, TG, and Lurie, JD.

Risk of Stroke After Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation in Medicare B

Beneficiaries Aged 66 to 99 Years With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Feb); 38 (2): 93–101Whedon, JM, Mackenzie, TA, Phillips, RB, and Lurie, JD.

Risk of Traumatic Injury Associated with Chiropractic Spinal

Manipulation in Medicare Part B Beneficiaries Aged 66-99

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015 (Feb 15); 40 (4): 264–270Dan NG, Saccasan PA.

Serious complications of lumbar spinal manipulation.

Med J Aust. 1983;2(12):672-673.Dupeyron A, Vautravers P, Lecocq J, Isner-Horobeti ME.

Evaluation de la frequence des accidents lies aux manipulations vertebrales a partir d'une

enquete retrospective realisee dans quatre departements francais.

[Complications following vertebral manipulation—a survey of a French region physicians].

Ann ReadaptMed Phys. 2003;46(1):33-40. [in French] .Hincapié, CA, Tomlinson, GA, Côté, P, Rampersaud, Y, Jadad, AR, and Cassidy, JD.

Chiropractic Care and Risk for Acute Lumbar Disc Herniation:

A Population-based Self-controlled Case Series

European Spine Journal 2018 (Jul); 27 (7): 1526–1537Rubinstein, S.M.

Adverse Events Following Chiropractic Care for Subjects With Neck

or Low-Back Pain: Do The Benefits Outweigh the Risks?

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008 (Jul); 31 (6): 461–464Gugliotta M, da Costa BR, Dabis E, et al.

Surgical versus conservative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: a prospective cohort study.

BMJ Open. 2016;6:(12) e012938.Johnson C, Rubinstein SM, Cote P, et al.

Chiropractic care and public health: answering difficult questions about safety,

care through the lifespan, and community action.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(7):493-513.Leach RA, Cossman RE, Yates JM.

Familiarity with and advocacy of Healthy People 2010 goals by Mississippi Chiropractic Association members.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34(6):394-406.Hawk C, Schneider MJ, Haas M, Katz P, Dougherty P, Gleberzon B, et al.

Best Practices for Chiropractic Care for Older Adults:

A Systematic Review and Consensus Update

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2017 (May); 40 (4): 217–229Jenkins HJ, Downie AS, Moore CS, French SD.

Current evidence for spinal X-ray use in the chiropractic profession: a narrative review.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2018;26:48.Globe, G, Farabaugh, RJ, Hawk, C et al.

Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 1–22Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, et al.

Best-practice recommendations for chiropractic management of patients with neck pain.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019;42 (9):635-650.Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, et al.

Best-Practice Recommendations for Chiropractic Management

of Patients With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 635-650Hawk C, Schneider MJ, Vallone S, Hewitt EG.

Best Practices for Chiropractic Care of Children:

A Consensus Update

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Mar); 39 (3): 158–168Bussières, AE, Stewart, G, Al Zoubi, F et al.

The Treatment of Neck Pain-Associated Disorders and

Whiplash-Associated Disorders: Clinical Practice Guideline

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Oct); 39 (8): 523–564Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, et al.

Low Back Pain of Mechanical Origin: Randomised Comparison of

Chiropractic and Hospital Outpatient Treatment

British Medical Journal 1990 (Jun 2); 300 (6737): 1431–1437Meade TW.

Effectiveness of chiropractic and physiotherapy in the treatment of low back pain:

a critical discussion of the British Randomized Clinical Trial.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1991;14(7):444-446.Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W.

Comparing hospital and chiropractic treatment for back pain: results were clinically trivial.

BMJ. 1995;311(7015):1302.Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, et al:

Randomised Comparison of Chiropractic and Hospital Outpatient

Management for Low Back Pain: Results from Extended Follow up

British Medical Journal 1995 (Aug 5); 311 (7001): 349–351Meade TW.

Patients were more satisfied with chiropractic than other treatments for low back pain

[letter, comment].

BMJ. 1999;319(7201):57.Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G, et al.

Acute Low Back Pain in Adults. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 14.

AHCPR Publication No. 95-0642. Rockville, MD:

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service,

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. December 1994.Coulter ID, Crawford C, Hurwitz EL, Vernon H, Khorsan R, Suttorp Booth M, Herman PM.

Manipulation and Mobilization for Treating Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Spine J. 2018 (May); 18 (5): 866–879Weigel, P.A., Hockenberry, J., Bentler, S.E., Wolinsky, F.D.

The Comparative Effect of Episodes of Chiropractic and

Medical Treatment on the Health of Older Adults

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Mar); 37 (3): 143–154Leininger BD, Evans R, Bronfort G.

Exploring Patient Satisfaction: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized

Clinical Trial of Spinal Manipulation, Home Exercise, and Medication

for Acute and Subacute Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Sep 5); 37 (8): 593–601Johnson PJ, Jou J, Rhee TG, Rockwood TH, Upchurch DM.

Complementary health approaches for health and wellness in midlife and older US adults.

Maturitas. 2016;89:36-42.Senna M.K., Machaly S.A.

Does Maintained Spinal Manipulation Therapy for Chronic Non-specific

Low Back Pain Result in Better Long Term Outcome?

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011 (Aug 15); 36 (18): 1427–1437Hawk C, Cambron JA, Pfefer MT.

Pilot Study of the Effect of a Limited and Extended Course of Chiropractic

Care on Balance, Chronic Pain, and Dizziness in Older Adults.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Jul); 32(6): 438–447Descarreaux M, Blouin JS, Drolet M, Papadimitriou S, Teasdale N:

Efficacy of Preventive Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Low-Back Pain

and Related Disabilities: A Preliminary Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (Oct); 27 (8): 509–514Eklund, A., I. Jensen, M. Lohela-Karlsson, J. Hagberg, C. Leboeuf-Yde, et al. (2018).

The Nordic Maintenance Care Program: Effectiveness of Chiropractic

Maintenance Care Versus Symptom-guided Treatment for

Recurrent and Persistent Low Back Pain -

A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial

PLoS One. 2018 (Sep 12); 13 (9): e0203029Leach R.

The Chiropractic Theories: A Textbook of Scientific Research. 4th ed.

Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004.Liliedahl RL, Finch MD, Axene DV, Goertz CM.

Cost of Care for Common Back Pain Conditions Initiated With

Chiropractic Doctor vs Medical Doctor/Doctor of Osteopathy

as First Physician: Experience of One Tennessee-Based

General Health Insurer

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Nov); 33 (9): 640–643Underwood M, UK BEAM Trial Team.

United Kingdom Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation (UK BEAM)

Randomized Tial: Effectiveness of Physical Treatments

for Back Pain in Primary Care

British Medical Journal 2004 (Dec 11); 329 (7479): 1377–1384Johnson M.R., Schultz M.K., Ferguson A.C.

A Comparison of Chiropractic, Medical and Osteopathic Care for Work-related Sprains and Strains

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1989 (Oct); 12 (5): 335–344Protecting the Integrity of Medicare Act of 2015,

HR 1021, 114th Cong, 1st Sess; 2015.Weeks WB, Leininger B, Whedon JM, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Swenson R, et al.

The Association Between Use of Chiropractic Care and Costs

of Care Among Older Medicare Patients With Chronic

Low Back Pain and Multiple Comorbidities

ipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(2):63–75Weeks WB, Goertz CM.

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Per Capita Supply of Doctors of Chiropractic

and Opioid Use in Younger Medicare Beneficiaries

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016 (May); 39 (4): 263–266Meerwijk EL, Larson MJ, Schmidt EM, et al.

Nonpharmacological treatment of army service members with chronic pain is associated with

fewer adverse outcomes after transition to the Veterans Health Administration.

J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(3):775-783.Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Kazal LA, Bezdjian S, Goehl JM, Greenstein J.

Impact of Chiropractic Care on Use of Prescription Opioids

in Patients with Spinal Pain

Pain Med. 2020 (Mar 6) [Epub]Davis, MA, Yakusheva, O, Gottlieb, DJ, and Bynum, JP.

Regional Supply of Chiropractic Care and Visits to

Primary Care Physicians for Back and Neck Pain

J American Board of Family Medicine 2015 (Jul); 28 (4): 481–490Whedon JM, Song Y, Davis MA.

Trends in the Use and Cost of Chiropractic Spinal

Manipulation Under Medicare Part B

Spine J. 2013 (Nov); 13 (11): 1449-1454Davis AY, O, Liu H, Tootoo J, Titler MG, Bynum JPW.

Access to Chiropractic Care and the Cost of Spine Conditions

Among Older Adults

American J Managed Care 2019 (Aug); 25 (8): e230–e236Whedon JM, Song Y.

Geographic variations in availability and use of chiropractic under medicare.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(2):101-109.Stevens GL.

Demographic and referral analysis of a free chiropractic clinic servicing ethnic minorities in the Buffalo,NY area.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(8): 573-577.Hawk C.

The use of chiropractic by special populations.

J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21(2):83-84.Barriers to Entry. Available at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Barriers_to_entry. Accessed August 15, 2020.Botta J.

Chiropractors healers or quacks? part 1: the 80-year war with science.

Consum Rep. 1975;40(9):542-547.Stussman BJ, Nahin RR, Barnes PM, Ward BW.

U.S. physician recommendations to their patients about the use of complementary health approaches.

J Altern Complement Med. 2020;26(1):25-33.Hurwitz EL, Randhawa K, Torres P, et al.

The Global Spine Care Initiative: a systematic review of individual and community-based burden

of spinal disorders in rural populations in low- and middle-income communities.

Eur Spine J. 2018;27 (Suppl 6):802-815.Chiropractic Medicare Coverage Modernization Act of 2019,

HR 3654, 116th Cong, 1st Sess; 2019.Haldeman S, Nordin M, Chou R, et al.

The Global Spine Care Initiative: World Spine Care executive summary on reducing spine-related

disability in low- and middle-income communities.

Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):776-785.

Return to MEDICARE

Since 12-19-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |