Spinal Manipulation vs Prescription Drug Therapy

for Chronic Low Back Pain: Beliefs, Satisfaction

With Care, and Qualify of Life Among

Older Medicare BeneficiariesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2021 (Oct); 44 (8): 663–673 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Anupama Kizhakkeveettil, PhD • Serena Bezdjian, PhD • Eric L. Hurwitz, PhD,

Ian Coulter, PhD • Scott Haldeman, PhD • James M. Whedon, DC, MS et. al

Ayurveda Medicine Department,

Southern California University of Health Sciences,

Whittier, California.

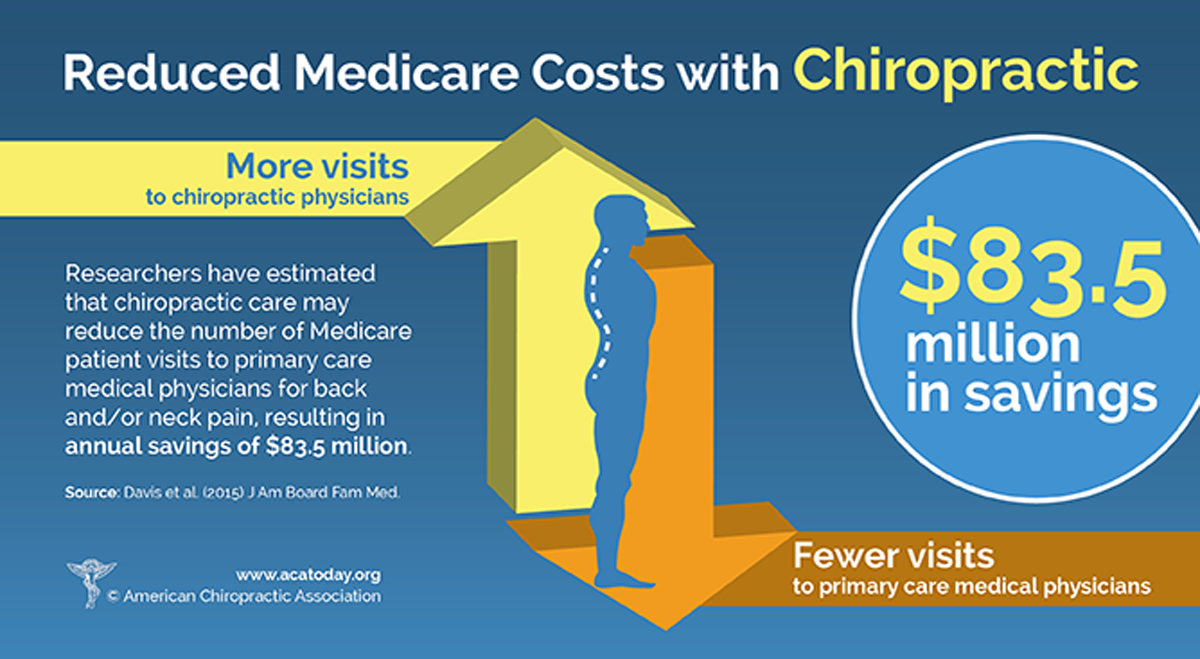

Davis ~ J Am Board Fam Med 2015Objective: The objective of this study was to compare patients' perspectives on the use of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) compared to prescription drug therapy (PDT) with regard to health-related quality of life (HRQoL), patient beliefs, and satisfaction with treatment.

Methods: Four cohorts of Medicare beneficiaries were assembled according to previous treatment received as evidenced in claims data: SMT, PDT, and 2 crossover cohorts (where participants experienced both types of treatments). A total of 195 Medicare beneficiaries responded to the survey. Outcome measures used were a 0–to–10 numeric rating scale to measure satisfaction, the Low Back Pain Treatment Beliefs Questionnaire to measure patient beliefs, and the 12–item Short Form Health Survey to measure HRQoL.

Results: Recipients of SMT were more likely to be very satisfied with their care (84%) than recipients of PDT (50%; P = .002). The SMT cohort self-reported significantly higher HRQoL compared to the PDT cohort; mean differences in physical and mental health scores on the 12–item Short Form Health Survey were 12.85 and 9.92, respectively. The SMT cohort had a lower degree of concern regarding chiropractic care for their back pain compared to the PDT cohort's reported concern about PDT (P = .03).

Conclusion: Among older Medicare beneficiaries with chronic low back pain, long-term recipients of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) had higher self-reported rates of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and greater satisfaction with their modality of care than long-term recipients of PDT. Participants who had longer-term management of care were more likely to have positive attitudes and beliefs toward the mode of care they received.

Keywords: Analgesics, Opioid; Low Back Pain; Manipulation, Spinal; Medicare; Prescription Drugs.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low back pain places a heavy burden on the health care system in the United States, with health care costs of $100 billion per year, [1] and chronic low back pain (cLBP) is the leading cause of disability worldwide. [2] The average age of adults with cLBP is increasing. [3] The 2012 National Health Interview Survey found that 19.3% of people aged 65 years and older had low back pain over a 3–month period. [1]

Spinal manipulation therapy (SMT) and prescription drug therapy (PDT) are both treatment strategies supported by evidence that are used under Medicare and widely used for short-term treatment of cLBP. [4] Spinal manipulation therapy, most commonly provided by chiropractors, has been established as an effective nonpharmacologic treatment for low back pain. [5, 6] Several clinical practice guidelines support the use of SMT for LBP. [7–10] Opioid analgesic therapy is a commonly used prescription drug therapy for low back pain in older people, [11] although opioids generally perform poorly with regard to patient satisfaction and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). [12–14] Patients including older Medicare beneficiaries receiving various treatments for cLBP have reported higher satisfaction with chiropractic care than with medical care. [15] However, for long-term supportive care of cLBP, the benefits of continuing these therapies are uncertain.

Currently, the relationship between treatment beliefs and patient experience, such as adherence to and satisfaction with treatment of cLBP, are unknown. These beliefs may play a role in treatment selection [16] and the ability to achieve clinically relevant improvement. [17] Understanding patients’ beliefs regarding treatment may help positively affect outcomes. For long-term management of cLBP, the comparative impact of SMT vs PDT on patient beliefs, HRQoL, and satisfaction with care has not been previously examined.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare patients’ perspectives on long-term use of SMT and PDT regarding beliefs about treatments, HRQoL, and satisfaction with treatment. We hypothesized that among older Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP, long-term recipients of SMT would have higher self-reported rates of HRQoL, more positive attitudes and beliefs about their mode of care, and greater satisfaction with their mode of are as compared with long-term recipients of PDT.

Methods

To test our hypothesis, a survey was conducted among older Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP.

Population

Potential survey participants were identified through analysis of Medicare claims data. The study population included noninstitutionalized Medicare Fee-for-Service beneficiaries, male and female, aged 65 to 84 years, as of January 1, 2012, residing in a U.S. state or the District of Columbia, and continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A (inpatient), B (outpatient), and D (pharmacy) from 2012 through 2016. We restricted the population to people with an episode of cLBP beginning in 2013. Chronic low back pain has previously been defined as lasting 3 months or longer, [18] thus an episode of cLBP was identified by 2 paid claims for outpatient office visits with a primary diagnosis of low back pain more than 90 days but less than 180 days apart. Claims were further restricted to the clinician specialties of general practice, family practice, internal medicine, osteopathic manipulative medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, chiropractic, physical therapist in private practice, and pain management. Low back pain was identified by ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis code (see Supplementary Data). All potential participants with any diagnosis of cancer or use of hospice care were excluded. An analytic data set of claims for 28,160 Medicare beneficiaries who met our inclusion criteria was assembled. Participants were grouped into 4 cohorts (defined later).

Ethics

The research methods were reviewed and approved by the principal investigators’ Southern California University of Health Sciences institutional review board. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03669354) as required by the National Institutes of Health.

Cohort Definitions

All participants received long-term management of cLBP with SMT or PDT. Spinal manipulation therapy was identified in clinical claims data by Current Procedural Terminology codes 98940, 98941, and 98942. Prescription drug therapy was identified as opioid analgesics or analgesics containing opioids, identified by drug codes and obtained by prescription through an outpatient pharmacy. For PDT, long-term management was defined as 6 or more standard 30-day-supply prescription fills in a 12-month period. [19, 20] For SMT, long-term management was defined as ≥12 office visits for spinal manipulation for low back pain in any 12-month period, including at least 1 visit per month.18 Two primary and 2 crossover cohorts were assembled as follows—primary cohorts: SMT = initiation in 2013 of long-term management with SMT, and no PDT for 12 months after initiating SMT; PDT = initiation in 2013 of long-term management with PDT, and no SMT for 12 months after initiating PDT; crossover cohorts: SMTX = any occurrence of SMT for cLBP in 2013, followed by initiation in 2013 of long-term management with PDT; PDTX = any occurrence of PDT for cLBP in 2013, followed by initiation in 2013 of long-term management with SMT

The date of accrual (index date) for participants into each cohort was the date of the first office visit associated with an episode of cLBP. For participants with more than 1 episode of cLBP, only the first episode was counted for the purposes of cohort accrual.

Sample Size

Based on power calculations, it was reasoned that a total sample size of 200 would allow for approximately 50 survey respondents per 4 cohort, estimating that 50 completed surveys per group would provide 85% power to detect Cohen effect sizes of 0.75 (three-quarters of a standard deviation) using a 5% type I error rate.

Survey Procedures

After cohort assembly, potential survey respondents were selected by random sampling from each of the 4 cohorts. The list of potential respondents was securely transmitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and initial contact was made by the CMS in the form of a Beneficiary Notification Letter, signed by the CMS privacy officer. This letter notified the selected potential respondents of the opportunity to participate in a health care survey, and allowed them the option to decline participation via enclosed reply forms. Upon conclusion of this process, the CMS provided us with contact information for potential respondents who had been determined to be eligible for voluntary participation in the survey. The CMS provided contact information for 2490 participants; beneficiaries who were deceased or without contact information were removed. A total of 1986 surveys were hand-addressed and mailed to the potential respondents on January 10, 2020. All available phone numbers were used to make reminder phone calls, and 2 weeks after the initial mailing, 1070 reminder surveys were re-sent to cohorts with lower response rates. The data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, with double data entry and data verification. Signed consent was obtained before participation in the study.

Outcome MeasuresOverall Satisfaction With SMT and PDT

The survey measured satisfaction for both SMT and PDT on a scale ranging from 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied). Participants were given an option to select “not applicable” if they never experienced either PDT or SMT. Prior studies have demonstrated that for quantifying satisfaction among patients, numeric rating scales can be used. [21, 22]

Beliefs About Treatments Received

This study used an 8-item assessment of participant beliefs regarding their treatment by SMT or PDT. These survey items were taken from a validated scale (Low Back Pain Treatment Beliefs Questionnaire) developed by Dima et al, with their permission. [16] A modified version of the Low Back Pain Treatment Belief Questionnaire was used for this study. Examples of belief items are “I think spinal manipulation is pretty useless for people with back pain” and “I believe Prescription Drug therapy (PDT) is pretty useless for people with back pain.” Responses on a 5-point Likert scale were strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree, and undecided. For purposes of analysis, the response options were combined into 3 categories: disagree (strongly disagree and disagree), agree (strongly agree and agree), and undecided (left as is).

Health-Related Quality of Life

A modified version of the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) outcome measure was used. The SF-12 is a validated HRQoL survey, [21] designed to be able to measure physical and mental health. A modified format of the original SF-12 survey was used to fit our population, [23] with the item and response presentations reformatted, using a larger font size. Permission to use the survey items in our study was granted by Optum.

The survey instrument was pretested for face validity by administration to 102 Medicare beneficiaries with chronic low back pain, aged over 65, who had received at least 2 chiropractic spinal manipulation treatments for their low back pain at the Southern California University of Health Sciences’ University Health Center. After examination of the face validity of the survey, and based on feedback, for ease of comprehension by older participants the survey questions were printed in larger font and carefully worded to be brief, unambiguous, and free from bias.Data Analysis

We generated descriptive statistics including means for continuous variables and percentages for categorical data. Between-groups differences were examined for our 3 measures. Specifically, outcomes for the SMT and PDT cohorts were compared to test our primary hypotheses, and outcomes for the SMTX and PDTX cohorts were subsequently compared as exploratory analyses. The Shapiro–Wilk test and assessment-of-normality plots were used to test for normality in the distribution of the data. Subsequently, the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test was used for the Beliefs About Treatment items to account for nonnormality in the data. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS (version 23; Armonk, New York).Overall Satisfaction With SMT and PDT

To compare SMT and PDT patients on level of satisfaction, the response options of the satisfaction scale were collapsed as follows: 8 to 10, Very Satisfied; <8, Less Satisfied. Pearson χ2 tests were conducted to examine differences between groups on the Overall Satisfaction With Treatment items. We performed t tests for group mean comparisons using the entire 0-to-10 scale for overall satisfaction as well.

Beliefs About Treatments Received

Additionally, for the Beliefs About Treatment items, we combined response options using the following categories: Disagree (combining strongly disagree with disagree), Agree (combining strongly agree with agree), and Undecided (left as is). Pearson χ2 tests were conducted to examine differences between groups for the Beliefs About Treatment items. Additionally, the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test was conducted to accommodate nonnormality in the distribution of the data for these items.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Group mean differences for the SF-12 mental and physical health scores were examined using t tests.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine patient self-reported overall satisfaction with SMT and PDT, HRQoL, and treatment beliefs among Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP. The results support the hypothesis that among older Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP, long-term recipients of SMT have higher self-reported rates of satisfaction with care received than do long-term recipients of PDT, which is consistent with prior work. [15, 24–30] The hands-on nature of SMT may lead to a greater perception of efficacy and thus to greater satisfaction compared to conventional medical treatment—perhaps due to a better practitioner-patient relationship and communication with patients. [31] McPhillips-Tangum et al report that many people with low back pain who received treatment from medical providers reported unmet needs and expectations, and conclude that satisfaction might be improved if providers consider patients’ perspectives and expectations. [32] Chiropractic care may be well suited to address the range of variables that affect patient satisfaction, including the patient-doctor relationship, perceived symptom improvement, and provision or communication of information about the condition. [33]

Understanding treatment beliefs in patients with low back pain will help develop evidence-based recommended interventions and thus may help improve treatment effectiveness and patient outcomes. In the present study, the SMT-only group self-reported significantly higher rates (of agreement) on the beliefs items pertaining to SMT than did the PDT-only group, whereas the PDT-only group self-reported higher rates of agreement with items pertaining to PDT. This suggests that people who have experienced longer-term management of care are more likely to have positive attitudes and beliefs toward that mode of care. Consistent with our expectation, there were no differences between crossover groups regarding self-reported beliefs about care received. However, the published literature in this area is limited, and further study is needed to provide a better understanding of the beliefs of patients who receive crossover care. Patient beliefs about treatment for cLBP may affect treatment selection, adherence, and satisfaction with care. [34–42] Further study is needed to better understand how to align treatments with patients’ beliefs.

Significantly higher scores for the SMT cohort on both the mental and physical components of the SF-12 indicates that those who received SMT on average had clinically meaningful higher self-reported physical and mental quality of life, consistent with previous reports. The present study's data on HRQoL are consistent with prior studies that have also reported improvement in subjective outcomes after SMT for low back pain. [43–48]

The time frame of this study was limited. There need to be further longer-term studies of cohorts of patients under SMT care versus opioid therapy to better understand the outcomes of these types of care.

A study conducted in the same population of Medicare beneficiaries from which the survey recipients in the present study were selected demonstrated lower overall costs under Medicare for SMT. [49] That study sample totaled 28< >160, 77% of whom initiated long-term care for cLBP with PDT and 23% with SMT. For care of low back pain, average long-term costs for those who initiated care with PDT were 58% lower than for those who initiated care with SMT. However, overall long-term health care expenditures under Medicare were 1.87 times higher for those who initiated care via PDT than for those initiated care with SMT (95% CI, 1.65–2.11; P < 0.0001). These results suggest that use of SMT offers a cost offset effect for long-term care for patients with cLBP. Thus SMT may not only offer a patient-centered approach for long-term care for LBP but may also offer cost savings.

Limitations

The overall response rate was 10%, and the PDT and SMTX cohorts had fewer participants than anticipated. Generalizability may be limited due to the low response rate. Additionally, we observed a statistically significant difference in age between respondents and nonrespondents, based on a 1–year difference in mean age; however, this small difference would not likely affect the estimates in a meaningful way. It is possible that respondents in the PDT group had more severe back pain and lower HRQoL at baseline, which may have influenced their responses. Additionally, since this study was survey-based, recall bias may pose an issue; but we have no reason to expect recall to be different between the cohorts. Moreover, participants’ reported HRQoL may be unrelated to prior treatments received for low back pain. As in any observational study, the results may be confounded by unmeasured variables. In this study, treatments received other than SMT or PDT may have confounded the results. Further study is needed to better understand patient beliefs regarding SMT versus PDT for cLBP.

Conclusion

Among older Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP, long-term recipients of SMT had higher self-reported rates of HRQoL and greater satisfaction with SMT than did long-term recipients of PDT. Participants who had longer-term management of care were more likely to have positive attitudes and beliefs toward the mode of care they received.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): A.K., J.M.W.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): A.K. A.W.J.T., T.A.M., J.D.L., J.M.W.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): A.K., S.B., E.L.H., A.W.J.T., T.A.M., J.D.L., I.C., S.H., J.M.W.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): A.K., S.B., E.L.H., A.W.J.T., D.R., S.U., K.S., M.B., T.A.M., J.D.L., I.C., S.H., J.M.W.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): A.K., S.B., E.L.H., J.M.W.

Literature search (performed the literature search): A.K., D.R., S.U., K.S., M.B.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): A.K., S.B., E.L.H., D.R., S.U., K.S., M.B.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): A.K., S.B., E.L.H., A.W.J.T., D.R., S.U., K.S., M.B., T.A.M., J.D.L., I.C., S.H., J.M.W.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

This research was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number 1R15AT010035. This project was 100% federally funded. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

J. M. W. reports a grant from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. J. D. L. reports grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study; and grants from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Food and Drug Administration, and SRS, as well as personal fees from Spinol and UptoDate, outside the submitted work.

S. H. reports being a consultant to Spinehealth.com while preparing this manuscript, travel-cost reimbursement from multiple conference lecture invitations, and research grants from Skoll, Musk, and NCMIC Foundations to World Spine Care for the Global Spine Care Initiative.

References:

Ghildayal N Johnson PJ Evans RL Kreitzer MJ.

Complementary and alternative medicine use in the US adult low back pain population.

Glob Adv Health Med. 2016; 5: 69-78Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, et al.:

Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) for 1160 Sequelae of 289 Diseases and Injuries 1990-2010:

A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

Lancet. 2012 (Dec 15); 380 (9859): 2163–2196Smith, M, Davis, MA, Stano, M, and Whedon, JM.

Aging Baby Boomers and the Rising Cost of Chronic Back Pain:

Secular Trend Analysis of Longitudinal Medical Expenditures

Panel Survey Data for Years 2000 to 2007

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013 (Jan); 36 (1): 2–11Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Coulter ID, Crawford C, Hurwitz EL, Vernon H, Khorsan R, Suttorp Booth M, Herman PM.

Manipulation and Mobilization for Treating Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Spine J. 2018 (May); 18 (5): 866–879Rubinstein SM, de Zoete A, van Middelkoop M, et al.

Benefits and Harms of Spinal Manipulative Therapy for the Treatment

of Chronic Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

of Randomised Controlled Trials

British Medical Journal 2019 (Mar 13); 364: l689Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, Decina P, Descarreaux M, Haskett D, Hincapie C, et al.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Other Conservative Treatments for Low Back Pain:

A Guideline From the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (May); 41 (4): 265–293Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, et al.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific

low back pain in primary care: an updated overview

European Spine Journal 2018 (Nov); 27 (11): 2791-2803Stochkendahl MJ, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J et al.

National Clinical Guidelines for Non-surgical Treatment of Patients with

Recent Onset Low Back Pain or Lumbar Radiculopathy

European Spine Journal 2018 (Jan); 27 (1): 60–75National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE):

Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management (PDF)

NICE Guideline, No. 59 2016 (Nov): 1–1067Jones MR Ehrhardt KP Ripoll JG et al.

Pain in the elderly.

Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016; 20: 23Desai R Hong YR Huo J.

Utilization of pain medications and its effect on quality of life, health

care utilization and associated costs in individuals with chronic back pain.

J Pain Res. 2019; 12: 557-569Krebs EE Gravely A Nugent S et al.

Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function

in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain:

the SPACE randomized clinical trial.

JAMA. 2018; 319: 872-882Mali J Nascimento J Atkinson J et al.

Chronic pain treatment satisfaction in musculoskeletal disease: differences between

osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain in medication switching,

opioid use, and utilization of non-pharmacologic treatments.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019; 27: S254Weigel, PA, Hockenberry, JM, and Wolinsky, FD.

Chiropractic Use in the Medicare Population: Prevalence, Patterns, and Associations

With 1-Year Changes in Health and Satisfaction With Care

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014 (Oct); 37 (8): 542-551Dima A Lewith GT Little P et al.

Patients’ treatment beliefs in low back pain:

development and validation of a questionnaire in primary care.

Pain. 2015; 156: 1489-1500Riis A Karran EL Thomsen JL et al.

The association between believing staying active is beneficial and achieving

a clinically relevant functional improvement after 52 weeks: a prospective

cohort study of patients with chronic low back pain in secondary care.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020; 21: 47R.A. Deyo, S.F. Dworkin, D. Amtmann, G. Andersson, et al.,

Report of the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain

Journal of Pain 2014 (Jun); 15 (6): 569–585Chou R Turner JA Devine EB et al.

The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain:

a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop.

Ann Intern Med. 2015; 162: 276-286Morden NE Munson JC Colla CH et al.

Prescription opioid use among disabled Medicare beneficiaries:

intensity, trends, and regional variation.

Med Care. 2014; 52: 852-859Chiarotto A Boers M Deyo RA et al.

Core outcome measurement instruments for clinical trials in nonspecific low back pain.

Pain. 2018; 159: 481-495Goertz CM, Long CR, Vining RD, Pohlman KA, Walter J, Coulter I.

Effect of Usual Medical Care Plus Chiropractic Care vs Usual Medical Care

Alone on Pain and Disability Among US Service Members With

Low Back Pain. A Comparative Effectiveness Clinical Trial

JAMA Network Open. 2018 (May 18); 1 (1): e180105 NCT01692275Ware Jr, J Kosinski M Keller SD

A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales

and preliminary tests of reliability and validity.

Med Care. 1996; 34: 220-233Andersson GB Lucente T Davis AM et al.

A comparison of osteopathic spinal manipulation with

standard care for patients with low back pain.

N Engl J Med. 1999; 341: 1426-1431Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, et al.

The Outcomes and Costs of Care for Acute Low Back Pain Among Patients

Seen by Primary Care Practitioners, Chiropractors, and Orthopedic Surgeons

New England J Medicine 1995 (Oct 5); 333 (14): 913–917Hurwitz EL.

The relative impact of chiropractic vs. medical management of

back pain on health status in a multispecialty group practice.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994; 17: 74-82Kane RL Olsen D Leymaster C et al.

Manipulating the patient: A comparison of the effectiveness of physician and chiropractor care.

Lancet. 1974; 1: 1333-1336Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, et al.

Low Back Pain of Mechanical Origin: Randomised Comparison

of Chiropractic and Hospital Outpatient Treatment

British Medical Journal 1990 (Jun 2); 300 (6737): 1431–1437Nyiendo J, Haas M, Goldberg B, Sexton G.

Patient Characteristics and Physicians' Practice Activities for

Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Practice-based Study

of Primary Care and Chiropractic Physicians

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001 (Feb); 24 (2): 92–100Nyiendo, J, Haas, M, and Goodwin, P.

Patient Characteristics, Practice Activities, and One-month Outcomes

for Chronic, Recurrent Low-back Pain Treated by Chiropractors and

Family Medicine Physicians: A Practice-based Feasibility Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2000 (May); 23 (4): 239–245Breen A, Breen R.

Back Pain and Satisfaction with Chiropractic Treatment:

What Role Does the Physical Outcome Play?

The Clinical Journal of Pain 2003 (Jul); 19 (4): 263–268McPhillips-Tangum CA Cherkin DC Rhodes LA Markham C.

Reasons for repeated medical visits among patients with chronic back pain.

J Gen Intern Med. 1998; 13: 289-295Maiers M, Hondras MA, Salsbury SA, Bronfort G, Evans R.

What Do Patients Value About Spinal Manipulation and Home Exercise for

Back-related Leg Pain? A Qualitative Study Within a Controlled Clinical Trial

Manual Therapy 2016 (Dec); 26: 183–191Bishop FL Yardley L Lewith GT

Treatment appraisals and beliefs predict adherence to complementary therapies:

a prospective study using a dynamic extended self-regulation model.

Br J Health Psychol. 2008; 13: 701-718Foster NE Bishop A Thomas E et al.

Illness perceptions of low back pain patients in primary care:

what are they, do they change and are they associated with outcome?

Pain. 2008; 136: 177-187Glattacker M Heyduck K Meffert C.

Illness beliefs, treatment beliefs and information needs as starting points

for patient information—evaluation of an intervention for patients with chronic back pain.

Patient Educ Couns. 2012; 86: 378-389Goldsmith R Williams NH Wood F.

Understanding sciatica: illness and treatment beliefs in a

lumbar radicular pain population: a qualitative interview study.

BJGP Open. 2019; 3 (bjgpopen19X101654)Grøn S Jensen RK Jensen TS Kongsted A.

Back beliefs in patients with low back pain: a primary care cohort study.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019; 20: 578Hagger MS Orbell S.

A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations.

Psychol Health. 2003; 18: 141-184Henderson CJ Orbell S Hagger MS.

Illness schema activation and attentional bias to coping procedures.

Health Psychol. 2009; 28: 101-107Horne R Weinman J.

Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in

adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness.

J Psychosom Res. 1999; 47: 555-567Horne R Weinman J.

Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of

illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication.

Psychol Health. 2002; 17: 17-32Gedin F, Dansk V, Egmar A-C, Sundberg T, Burström K (2018)

Patient-reported Improvements of Pain, Disability, and Health-related Quality of Life

Following Chiropractic Care for Back Pain - A National Observational Study in Sweden

J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2019 (Apr); 23 (2): 241–246Kizhakkeveettil A Rose KA Kadar GE Hurwitz EL.

Integrative acupuncture and spinal manipulative therapy versus either alone

for low back pain: a randomized controlled trial feasibility study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017; 40: 201-213Sarker K Sethi J Mohanty U.

Effect of spinal manipulation on specific changes in segmental instability,

pain sensitivity and health-related quality of life among patients

with chronic non-specific low back pain—a randomized clinical trial.

Annu Res Rev Biol. 2017; 18: 1-10Sarker KK Sethi J Mohanty U.

Effect of spinal manipulation on pain sensitivity, postural sway,

and health related quality of life among patients with non-specific

chronic low back pain: a randomised control trial.

J Clin Diagn Res. 2019; 13: YC01-YC05Underwood M, UK BEAM Trial Team.

United Kingdom Back Pain Exercise and Manipulation (UK BEAM) Randomized Trial:

Effectiveness of Physical Treatments for Back Pain in Primary Care

British Medical Journal 2004 (Dec 11); 329 (7479): 1377–1384Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Sherbourne CD, Ryan GW, Coulter ID.

Group and Individual-level Change on Health-related Quality of Life

in Chiropractic Patients With Chronic Low Back or Neck Pain

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019 (May 1); 44 (9): 647–651Whedon J, Kizhakkeveettil A, Toler A, et al.

Long-Term Medicare Costs Associated with Opioid Analgesic Therapy

vs Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain in a Cohort of Older Adults

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2022; 44 (7): 519-526.

Return to MEDICARE

Return LOW BACK PAIN

Return to PATIENT SATISFACTION

Since 5-07-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |