Changes in Female Veterans' Neck Pain Following

Chiropractic Care at a Hospital for VeteransThis section was compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018 (Feb); 30: 91–95 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Kelsey L.Corcoran DC, Andrew S.Dunn DC, MEd, MS, Bart N.Green DC, MSEd, PhD,

Lance R.Formolo DC, MS, Gregory P.Beehler PhD, MA

Chiropractic Department,

Medical Care Line,

VA Western New York,

3495 Bailey Ave,

Buffalo, NY 14215, USA

OBJECTIVE: To determine if U.S. female veterans had demonstrable improvements in neck pain after chiropractic management at a Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital.

METHODS: This was a retrospective cross-sectional study of medical records from female veterans attending a VA chiropractic clinic for neck pain from 2009 to 2015. Paired t-tests were used to compare baseline and discharge numeric rating scale (NRS) and Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire (NBQ) scores with a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) set at a 30% change from baseline.

RESULTS: Thirty-four veterans met the inclusion criteria and received a mean of 8.8 chiropractic treatments. For NRS, the mean score improvement was 2.7 (95%CI, 1.9–3.5, p < .001). For the NBQ, the mean score improvement was 13.7 (95%CI, 9.9–17.5, p < .001). For the MCID, the average percent improvement was 45% for the NRS and 38% for the NBQ.

CONCLUSION: Female veterans with neck pain experienced a statistically and clinically significant reduction in NRS and NBQ scores.

KEYWORDS: Chiropractic; Neck pain; Veterans; Women

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Neck pain is a common complaint among U.S. military active duty personnel and veterans. [1–5] The causes of neck pain are many, and for those involved with the military they can range from military office work [1] to significant combat trauma. [2] In the veteran population, painful musculoskeletal diagnoses are widespread. [6] Musculoskeletal conditions are the leading cause of morbidity for female veterans [7] and among all veterans with musculoskeletal pain, women are more likely to experience neck pain than men. [3]

Today, more women are entering the military than ever before. Women currently comprise 14% of those enlisted within the Department of Defense services. [8] Post-military separation, 32% of women enroll in Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services, a historic high for this population. [8] Determining safe and effective pain management strategies for women with musculoskeletal pain is particularly important as there are indications that over prescription of opioid medications may have a greater negative effect on women than men. [9] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describe prescription painkiller overdoses as an “under-recognized” and increasing problem for women. [9] There has been a 400% increase in overdose deaths since 1999 for women (compared to a 265% increase for men) and currently 1 in 10 suicides by women in the United States involves prescription painkillers, which the CDC defines as opioids or narcotics. [9] This trend holds true in the veteran population, where substance use disorders, including opioid misuse, are more strongly associated with suicide for women than for men. [10]

One potential non-pharmacological treatment option for musculoskeletal pain is chiropractic care. VHA patients are referred to chiropractic services for a variety of musculoskeletal complaints and neck conditions comprise 24.3% of all referrals, the second leading reason for referral after lowback conditions. [11]While 15.8% of VHA chiropractic patients are currently female [11], little is known specifically about female veterans' outcomes with chiropractic management [12]. To our knowledge, no study has examined female veterans' outcomes with chiropractic care for neck pain. The objective of this paper was to determine if female veterans had demonstrable improvements in neck pain after chiropractic management within a Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital. Our hypothesis was that female veterans would have statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in neck pain following care.

Methods

Study design

This study was a cross-sectional retrospective medical records review. This protocol was reviewed and approved before commencing the study through the VA Western New York Healthcare System (VAWNYHS) Research and Development Committee and Institutional Review Board.

Setting

The chiropractic clinic at VAWNYHS served as the setting for this study.

Participants and variables

All female veterans who were 18e89 years of age at intake and were consulted to chiropractic services during the period January 1, 2009 through December 31, 2015 for a chief complaint of neck pain were eligible for analysis. Patients were excluded if they had received less than 2 chiropractic treatments, if they had a baseline numerical rating scale (NRS) of less than 2 out of 10 or a baseline Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire (NBQbody mass index (BMI), and service-connected (SC) disability percentage. SC disabilities are injuries or illnesses that are incurred or aggravated during active military service, for which veterans who separated or were discharged from the military under honorable circumstances may be eligible for compensation. [13]

The NRS is an 11–point assessment for pain severity with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing “worst pain imaginable”. [14] The NBQ is a multidimensional outcome measure based upon the biopsychosocial model of pain. [15–17] The NBQ is a validated 7–question instrument with scores ranging from 0 to 70 with higher scores representing increased symptom severity. [15–17] NRS and NBQ scores were collected at initial consultation with NRS collected at each follow-up visit and NBQ collected again at the time of re-evaluation. For the purposes of this study, both the number of chiropractic treatments and final outcome measures were collected on either the date of formal discharge by the chiropractic physician or from the last follow-up visit to the chiropractic clinic that was within two months from the previous chiropractic appointment in the event that the patient selfdiscontinued care.

Data sources

Data were extracted from medical records into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) by one of two investigators and added to a prospectively maintained quality assurance data set. A third investigator verified the accuracy of the quality assurance data set by comparison to the medical records for all female veterans meeting inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies found were corrected using data from the medical records.

Chiropractic treatment methods and frequency

This was a pragmatic design and the type of manual therapy chosen was at the discretion of the provider, considering the presentation of the individual patient, patient preference, and the clinical judgement of the provider. The type of manual therapy varied among patients and among visits, but typically included spinal manipulative therapy (SMT), spinal mobilization, flexion-distraction therapy, and/or myofascial release. SMT was operatively defined as a manipulative procedure involving the application of a high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust to the cervical spine. [18] Spinal mobilization was defined as a form of manually assisted passive motion involving repetitive joint oscillations typically at the end of joint play and without the application of a high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust. [18] Flexion-distraction therapy is a gentle form of unloaded spinal manipulation involving traction components along with manual pressure applied to the neck in a prone position. [18] Myofascial release was defined as manual pressure applied to various muscles either in a static state or while undergoing passive lengthening. Patients also received education about improving posture and stretching recommendations appropriate to their condition.

A typical course of care involved one treatment every one to two weeks with re-evaluation and review of updated outcome measures every fourth treatment or earlier if indicated. Care was delivered by one of two staff chiropractors with some contributions by supervised final-year chiropractic students. The number of treatments provided was calculated by frequency counts.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics pertaining to race, age, BMI, SC disability percentages and number of treatments were calculated for the sample.

BMI categories were designated using those of the CDC:underweight (<18.5 kg/m2),

normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2),

overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2),

obese (≥30.0 kg/m2). [19]Sample size for paired t-tests was determined using power analysis in G* Power 3.1.9.2 for Windows (Universit€at Düsseldorf, Germany) [20] assuming an alpha of 0.05, a power of 0.80, and a medium effect size (p = 0.5) for a 1–tailed test. The required sample size was determined to be 27. NRS and NBQ data were assessed using the Shapiro Wilk test and met the assumption of normality necessary to run paired t-tests.

Paired t-tests were used to compare baseline and discharge scores for NRS and NBQ with alpha <.05 and a Bonferroni correction of 2 to account for the multiple comparisons between means. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's d.

In addition to statistical significance, clinical significance was assessed using a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of an average 30% or greater change from baseline to discharge for both the NRS and NBQ. MCIDwas based upon published accounts of an international consensus for a range of commonly used back pain outcome measures. [21] The percentage of patients who reached or exceeded the MCID for the measures used are reported. All data, except for the sample size estimate, were analyzed using SPSS Statistics forWindows, version 22 (IBMInc, Armonk,NewYork).

Results

Participants

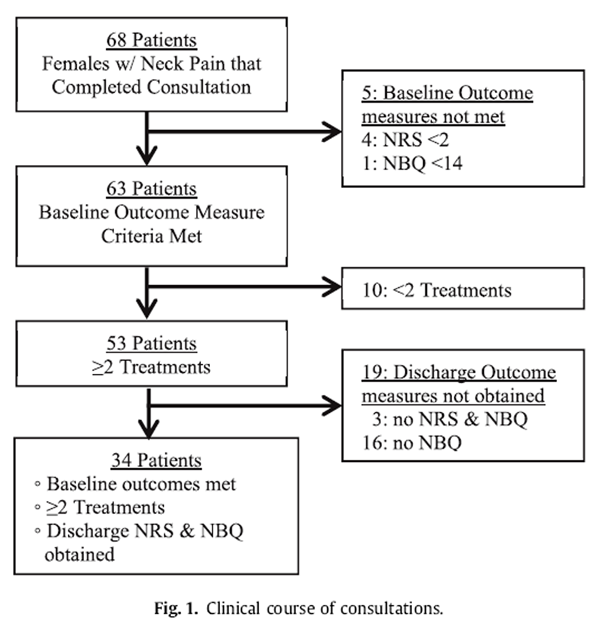

Figure 1

Table 1

Table 2 Sixty-eight female veterans with neck pain were treated between 2009 and 2015 and 34 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Seventy-nine percent (n = 27) of the sample was white, 12% (n = 4) was black, 9% (n = 3) was of unknown race and there were no Asian or Hispanic/Latino veterans. BMI categorical data were: underweight 6% (n = 2), normal 21% (n = 7), overweight 32% (n = 11), obese 41% (n = 14). Further descriptive data for age, BMI, percent SC disability, NRS and NBQ are presented in Table 1.

Main results

There was a significant decrease in NRS scores from baseline (x = 6.2, SD = 2.1) to discharge (x = 3.5, SD = 2.6) and a significant decrease in NBQ scores from baseline (x = 37.6, SD = 14.0) to discharge (x = 23.9, SD = 14.6). The mean reduction in NRS scores was 2.7 (95%CI, 1.9–3.5). The mean reduction in NBQ scores was 13.7 (95%CI, 9.9–17.5). Results of the paired t-tests are shown in Table 2. Cohen's d indicated large effect sizes. For the MCID, the average percent improvement was 45% for the NRS and 38% for the NBQ, with 62% and 65% of patients meeting or exceeding the MCID for the NRS and NBQ, respectively. No significant adverse events were reported for any of the patients in the sample.

Discussion

In this study, there were significant decreases in numeric rating scale (NRS) and Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire (NBQ) scores that were clinically significant based on published minimum clinically important difference (MCID) percentages.

The majority of veterans who met the inclusion criteria for this study were overweight or obese. Obesity is associated with a host of comorbid condition and disability in the chronic pain population including back pain [22–24], sciatica [25], and spinal degenerative changes. [26] The high prevalence of obesity in the sample population is consistent with the overall trend of poorer health in the U.S. veteran population, which carries twice the illness burden of civilian ambulatory patients. [27] Average SC disability percentage in the sample was over 50%. Individuals with disability status are known to have an increase in all-cause mortality rates. [28]

Despite indications and risk factors for suboptimal overall health, female veterans in the present study receiving chiropractic management for neck pain had demonstrable improvement which was statistically and clinically significant. Improvement in outcome measures was particularly robust given the chronicity of pain complaints typically seen at VHA chiropractic clinics, which is partly due to the time between military service and postdeployment VHA medical care, especially in the case of SC conditions. The selection of a MCID value is somewhat fluid, and there is no clear gold standard for the outcome measures in this study population. Experts on MCID for chronic pain clinical trials have suggested that even 10e20% improvements from baseline may represent a MCID in chronic pain populations. [29] In contrast, Hurst and Bolton (2004) concluded that a 34% improvement to the Bournemouth Questionnaire had the highest sensitivity and specificity for differentiating clinically significant improvement from no improvement in neck pain patients treated by community chiropractors in England. [30] While a 30% improvement was selected for a MCID in this study, given several factors specific to the VHA patient population a lower MCID may have been justified and would have increased the average percent improvement and percent of individuals who exceeded the MCID during a course of care.

The results of this study are consistent with those of crosssectional studies of predominantly male patients at the VAWNYHS chiropractic clinic and others. A sample of veterans with neck pain that was 87% male saw a mean reduction in NRS scores of 2.6 (42.9% improvement) and a mean score reduction in NBQ of 13.9 (33.1% improvement) after a course of chiropractic care. [31] This suggests that female veterans in the present study demonstrated similar improvement following chiropractic care for neck pain compared to the overall population seen at the VAWNYHS clinic. Additional research on the chiropractic management of neck pain in the veteran population is limited to two retrospective chart reviews where other chief complaints were also included. The mainly male veterans with musculoskeletal pain in these studies also demonstrated improvement in outcomes following chiropractic management [32, 33], however, none of the aforementioned studies included a control group.

At the time of this study, no randomized controlled trials had been conducted evaluating chiropractic management for neck pain in the veteran population and there was no literature specifically about chiropractic care for female veterans with neck pain. Research from the civilian population supports the use of SMT and mobilization for the management of neck pain [34–37], and these manual therapies are incorporated in the American Physical Therapy Association's Clinical Practice Guidelines for Neck Pain. [37] While a causal relationship cannot be established due to the retrospective and cross-sectional designs of the studies discussed above, these data suggest that prospective randomized controlled trials could be considered to further to investigate if chiropractic care is an effective conservative treatment option for female veterans with neck pain.

Limitations

Study limitations include those inherent to the nature of retrospective design including a lack of control for other variables that may have affected treatment response, the small sample size, and regional variations in the veteran population and clinical practice preferences. As such, no causal inferences can be made from the data presented. While treatments were generally provided at a frequency of once per every one to two weeks with NRS collected at every treatment and NBQ being collected after every four treatments, variations in that frequency and the duration of care occurred and may have had an influence on the clinical outcomes. Analysis was based upon 34 patients who met the inclusion criteria, which was 50% of the clinic's population of female veterans with neck pain. A large number of patients were excluded due to a lack of discharge outcomes representing patients who were lost to follow-up or discharged prior to a formal re-evaluation. There are many potential factors which may influence veterans completing a course of care as planned. For female veterans in particular, surveys have identified that transportation, access to childcare, and inconvenient appointment times are some of the barriers to receiving on-station VHA care. [38]

Conclusion

Female veterans with neck pain included in this study experienced statistically and clinically significant reductions in numeric rating scale (NRS) and Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire (NBQ) scores over a short course of chiropractic management with a mean of 8.8 treatments. Chiropractic management may be an effective treatment strategy for female veterans with neck pain complaints. Further research is warranted given the lack of published evidence.

Funding sources

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VAWestern New York Healthcare Center.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Disclaimer

The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government, Stanford University, Stanford Health Care, or Qualcomm.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgements.

References:

V. De Loose, F. Burnotte, B. Cagnie, et al.,

Prevalence and risk factors of neck pain in military office workers,

Mil. Med. 173 (2008) 474.S.P. Cohen, S.G. Kapoor, C. Nguyen, et al.,

Neck Pain During Combat Operations: An Epidemiological Study

Analyzing Clinical and Prognostic Factors

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010 (Apr 1); 35 (7): 758–763D.M. Higgins, B.T. Fenton, M.A. Driscoll, et al.,

Gender differences in demographic and clinical correlates among veterans with musculoskeletal disorders, 10.1016, Womens Health Issues (2017). Available at:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S104938671630130XB.N. Green, A.S. Dunn, S.M. Pearce, et al.,

Conservative Management of Uncomplicated

Mechanical Neck Pain in a Military Aviator

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2010 (Jun); 54 (2): 92–99Passmore, SR and Dunn, AS.

Positive Patient Outcome After Spinal Manipulation in a Case of Cervical Angina

Man Ther. 2009 (Dec); 14 (6): 702–705VHA Office of Public Health and Environmental Hazards:

Analysis of VHA Healthcare Utilization Among Global War on Terrorism (GWOT)

Veterans, Veterans Health Administration, Washington, DC, 2009. Available at:

http://www.networkofcare.org/library/GWOT_4th%20Qtr%20FY08%20HCU.pdf.Department of Veterans Affairs, Women's Health Evaluation Initiative:

Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration, vol. 3,

Veterans Health Administration, Washington, DC, 2014. Available at:

http:// www.womenshealth.va.gov/docs/Sourcebook_Vol_3_FINAL.pdf.Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics:

America's Women Veterans: Military Service History and VA Service Benefit Utilization Statistics,

Veterans Health Administration, Washington, DC, 2011. Available at:

http://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/final_womens_report_3_2_12_v_7.pdf.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

Prescription Painkiller Overdoses: a Growing Epidemic, Especially Among Women,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, 2013. Available at:

https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/prescriptionpainkilleroverdoses/index.html.K.M. Bohnert, M.A. Ilgen, S. Louzon, et al.,

Substance use disorders and the risk of suicide mortality among men and women

in the US Veterans Health Administration,

Addiction 112 (7) (2017) 1193-1201.A.J. Lisi, C.A. Brandt,

Trends in the Use and Characteristics of Chiropractic Services

in the Department of Veterans Affairs

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jun); 39 (5): 381–386Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ.

Integration of Chiropractic Services in Military and Veteran Health Care Facilities:

A Systematic Review of the Literature

J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016 (Apr); 21 (2): 115–130Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs,

Federal Benefits for Veterans, Dependents and Survivors

Chapter 2 Service-connected Disabilities

US Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC, 2015.W.W. Downie, P.A. Leatham, V.M. Rhind, et al.,

Studies with pain rating scales,

Ann. Rheum. Dis. 37 (1978) 378-381.J.E. Bolton, B.K. Humphreys,

The Bournemouth Questionnaire: A Short-form Comprehensive Outcome Measure. II.

Psychometric Properties in Neck Pain Patients

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2002 (Mar); 25 (3): 141-148Bolton JE.

Sensitivity And Specificity Of Outcome Measures In Patients

With Neck Pain: Detecting Clinically Significant Improvement

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004 (Nov 1); 29 (21): 2410-2417H. Hurst, J. Bolton,

Assessing the Clinical Significance of Change Scores

Recorded on Subjective Outcome Measures

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (Jan); 27 (1): 26–35J. Triano,

The mechanics of spinal manipulation,

in: W. Herzog (Ed.), Clinical Biomechanics of Spinal Manipulation,

Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, 2000, pp. 92e190.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

Healthy Weight: About Adult BMI, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

Atlanta, GA, 2015. Available at:

https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html.F. Faul, E. Erdfelder, A. Buchner, et al.,

Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation

and regression analyses,

Behav. Res. Meth. 41 (4) (2009) 1149-1160.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole MR.

Clinical Importance of Changes in Chronic Pain Intensity

Measured on an 11-point Numerical Pain Rating Scale

Pain 2001 (Nov); 94 (2): 149-158R. Shiri, J. Karppinen, P. Leino-Arjas, S. Solovieva, E. Viikari-Juntura,

The association between obesity and low back pain: a meta-analysis,

Am. J. Epidemiol. 171 (2) (2010) 135e154,

https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp356,20007994.R. Shiri, J. Karppinen, P. Leino-Arjas, et al.,

The association between obesity and low back pain: a meta-analysis,

Am. J. Epidemiol. 171 (2) (2010) 135-154.W.D. Paulis, S. Silva, B.W. Koes, et al.,

Overweight and obesity are associated with musculoskeletal complaints as early as childhood:

a systematic review,

Obes. Rev. 15 (1) (2014) 52-67.C.E. Cook, J. Taylor, A. Wright, et al.,

Risk factors for first time incidence sciatica: a systematic review,

Physiother. Res. Int. 19 (2) (2014) 65-78.A.B. Dario, M.L. Ferreira, K.M. Refshauge, et al.,

The relationship between obesity, low back pain, and lumbar disc degeneration when genetics

and the environment are considered: a systematic review of twin studies,

Spine J. 15 (5) (2015) 1106-1117.W.H. Rogers, L.E. Kazis, D.R. Miller, et al.,

Comparing the health status of VA and non-VA ambulatory patients:

the veterans' health and medical outcomes studies,

J. Ambul. Care Manag. 27 (2004) 249-262.V.L. Forman-Hoffman, K.L. Ault, W.L. Anderson, et al.,

Disability status, mortality, and leading causes of death

in the United States community population,

Med. Care 53 (4) (2015) 346-354.R.H. Dworkin, D.C. Turk, K.W. Wyrwich, et al.,

Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials:

IMMPACT recommendations,

J. Pain 9 (2) (2008) 105-121.H. Hurst, J. Bolton,

Assessing the Clinical Significance of Change Scores

Recorded on Subjective Outcome Measures

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (Jan); 27 (1): 26–35A.S. Dunn, B.N. Green, L.R. Formolo, et al.,

Chiropractic Management for Veterans with Neck Pain:

A Retrospective Study of Clinical Outcomes

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011 (Oct); 34 (8): 533–538Dunn, AS, Passmore, SR, Burke, J, and Chicoine, D.

A Cross-sectional Analysis of Clinical Outcomes Following Chiropractic

Care in Veterans With and Without Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Military Medicine 2009 (Jun); 174 (6): 578–583A.J. Lisi,

Management of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom

Veterans in a Veterans Health Administration Chiropractic Clinic: A Case Series

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010; 47 (1): 1–6Bronfort G Haas M Evans RL et al.

Efficacy of Spinal Manipulation and Mobilization for Low Back Pain and Neck Pain:

A Systematic Review and Best Evidence Synthesis

Spine J (N American Spine Soc) 2004 (May); 4 (3): 335–356R. Bryans, P. Decina, M. Descarreaux, et al.,

Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Chiropractic Treatment of Adults With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Jan); 37 (1): 42–63A.R. Gross, J.L. Hoving, T.A. Haines, et al.,

Cochrane review of manipulation and mobilization for mechanical neck disorders,

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 29 (14) (2004) 1541-1548.J.D. Childs, J.A. Cleland, J.M. Elliott, et al.,

Neck pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification

of functioning, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the

American Physical Therapy Association,

J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 38 (9) (2008) A1-A34.Department of Veterans Affairs,

Study of Barrier for Women Veterans to VA Healthcare,

Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC, 2015. Available at:

http://www.womenshealth.va.gov/docs/Womens%20Health%20Services_Barriers

%20to%20Care%20Final%20Report_April2015.pdf

Return to CHRONIC NECK PAIN

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 2-06-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |