Chiropractic Clinical Outcomes Among Older Adult

Male Veterans With Chronic Lower Back Pain:

A Retrospective Review of Quality-Assurance DataThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Chiropractic Medicine 2022 (Jun); 21 (2): 77–82 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Brian A. Davis DC, Andrew S. Dunn DC, MS, MEd, Derek J. Golley DC, MS, Dave R. Chicoine DC, MS

Chiropractic Department,

VA Western New York Healthcare System,

Buffalo, New York

FROM: Military.com 2019Objective: The purpose of this study was to determine whether a sample of older adult male U.S. veterans demonstrated clinically and statistically significant improvement in chronic lower back pain on validated outcome measures after a short course of chiropractic care.

Methods: We performed a retrospective review of a quality-assurance data set of outcome metrics for male veterans, aged 65 to 89 years, who had chronic low back pain, defined as pain in the lower back region present for at least 3 months before evaluation. We included those who received chiropractic management from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2018. Paired t tests were used to compare outcomes after 4 treatments on both a numeric rating scale (NRS) and the Back Bournemouth Questionnaire (BBQ). The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) was set at 30% change from baseline.

Results: There were 217 individuals who met the inclusion criteria. The mean NRS score change from baseline was 2.2 points, representing a 34.1% reduction (t = 13.5, P < .001). The mean score change for BBQ was 14.7 points, representing a 35.9% reduction (t = 16.7, P < .001). The percentage of participants reaching the MCID for the NRS was 57% (n = 124) and for the BBQ was 59% (n = 126), with 41% (n = 90) of the sample reaching the MCID for both the NRS and BBQ.

Conclusion: This retrospective review revealed clinically and statistically significant improvement in numeric rating scale (NRS) and Back Bournemouth Questionnaire (BBQ) scores for this sample of older male U.S. veterans treated with chiropractic management for chronic low back pain.

Keywords: dult; Chiropractic; Low Back Pain; Manipulation, Spinal; Veterans.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Trends in aging demonstrate that the U.S. and worldwide populations are getting older and will continue to progress in a fashion that further increases the proportion of older individuals. [1, 2] The proportion of the U.S. population aged ≥65 years is projected to increase from 12.4% in 2000 to approximately 20% in 2030, from 35 million to 71 million people. [1, 2] This has implications for health care services worldwide, including the Veterans Health Administration division of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). [3] These implications are especially pronounced within the VA, as the average health status of older veteran enrollees is poorer than that of older individuals enrolling in Medicare managed care. [3] Of note, according to the Veteran Population Projection Model 2018, the veteran population is expected to decline from 19.5 million in 2020 to 13.6 million by 2048 — a 1.8% reduction per year. However, despite the slow projected decline over the next 3 decades, the current older veteran population remains a robust patient base.

Older adults, those aged 65 years or older, commonly report experiencing lower back pain (LBP; 25%–33% annually). [4–6] Although the overall prevalence of LBP is similar to that in the younger working-age population, the prevalence of disabling LBP and the complexity of its presentation among older adults are much greater than in their younger counterparts. [4–7] Factors which potentially worsen prognosis in LBP are more common among older adults, including longer duration of symptoms, the presence and increased severity of degenerative changes, medical comorbidities, and decreased functional status [7]

The Global Burden of Disease Study defines disability as “any short-term or long-term health loss” to create time-based metrics called years lived with disability (YLD) and disability-adjusted life years to compare the worldwide burden of various diseases. Of all conditions, LBP was the greatest contributor of YLD, accounting for 10.7% of all YLD and 83 million disability-adjusted life years. [8] It also carries a strong economic burden. In the United States alone, the estimated annual costs associated with LBP are between $100 billion and $200 billion, with the majority (52%–54%) being indirect costs. [9]

When considering a management approach for chronic LBP, veterans have many treatment options within the VA, including chiropractic management. [10] Chiropractic management has demonstrated efficacy in the management of LBP in older adults in previous studies, both within [11] and outside [12–15] the VA.

There are few studies reporting the use of chiropractic care for older veterans, and thus there is justification and significance in exploring chronic LBP management among older veterans. Although there is a high prevalence of LBP in this population, [16] there is a paucity of studies regarding clinical outcomes with chiropractic management of chronic LBP within this specific population. The purpose of this retrospective study was to determine whether a sample of older adult male U.S. veterans would demonstrate clinically and statistically significant improvement of validated outcome measures for chronic LBP after a short course of chiropractic care.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a retrospective review of outcome metrics using a prospectively maintained quality-assurance data set. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the VA Western New York Healthcare System Institutional Review Board before commencement of the study.

Study Setting

The chiropractic clinic at the Buffalo VA Medical Center (VAMC) was the setting for this study.

Population Sample

The following were the inclusion criteria: male, veteran, age 65 to 89 years at intake, evaluation for chronic LBP by the local VA chiropractic service during the period from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2018, and completed outcome measures at baseline and at follow-up after 4 treatments. Although participants may have had more treatment visits, we selected 4 treatments as the point in time for this study because typically this is when clinicians make decisions about patient response to care. This is also typically the time when information is gathered to guide patient management early within a course of care, in terms of both clinical response and resource allocation.

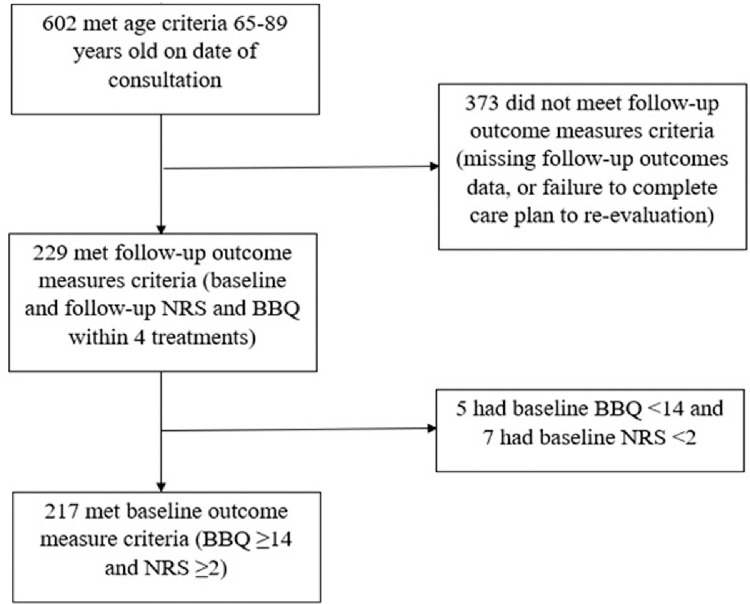

The format of the prospectively maintained quality-assurance data set changed in 2019, precluding inclusion of clinical encounters beyond 2018. Chronic LBP within our sample was defined as pain in the lower back region present for at least 3 months before evaluation. Patients were excluded if they were missing initial or follow-up pain numeric rating scale (NRS) or Back Bournemouth Questionnaire (BBQ) values or if they had a baseline NRS of <2 out of 10 or a baseline BBQ score of <14 out of 70, to best allow for a reasonable measure of treatment response by limiting floor effects. Data from those patients who met the inclusion criteria were included in the statistical analysis. A small number of veterans presented for consultation in the clinic more than once during the 9–year period; data were collected from each individual course of care as long as a minimum of 1 year had passed between the last follow-up visit and the subsequent consultation.

Data Collection

An electronic quality-assurance data set in the form of a Microsoft Excel file within a local secure VA drive was used as the data source for this study. Data points were entered into the quality-assurance file directly after the initial consultation and individual re-evaluations by the staff chiropractors at the facility between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2018. The data were extracted from that quality-assurance data set into a separate Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. All identifying information was scrubbed from the workable data set. Descriptive variables were collected including age, body mass index (BMI), baseline BBQ and NRS scores, re-evaluation BBQ and NRS scores, service-connected (SC) disability percentage, and SC percentage for the chief complaint. Scores for the NRS were collected at baseline and every follow-up visit, and BBQ scores were collected at baseline and again after 4 treatments at the time of re-evaluation on the fifth appointment. The decision to collect outcome measures after 4 treatments was based on the Nordic back pain subpopulation studies, [17–19] which support the concept that the early response to care is predictive of the overall response to care. The NRS is an 11–point self-reported assessment of pain severity, with 0 representing “no pain” and 10 representing the “worst pain imaginable.” [20] The BBQ is a validated 7–question multidimensional outcome measure based on the biopsychosocial model of back pain. Final BBQ scores range from 0 to 70 based on the sum of 7 multifactorial questions scored 0 to 10, with higher scores associated with increased symptom severity. [21] Service-connected disabilities are injuries or illnesses that are incurred or aggravated during active military service, for which veterans who separated or were discharged from the military under honorable circumstances may be eligible for compensation. [22]

Chiropractic Treatment Methods and Frequency

This was a review of the routine clinical chiropractic care performed within the facility. A multimodal approach was carried out based upon the presentation of the individual patient, patient preference, and the clinical judgement of the provider. The nature of the therapy applied for treatment and individual treatment visits varied, but typical chiropractic care within the Buffalo VAMC may have included a combination of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT), spinal mobilization techniques, flexion-distraction therapy, therapeutic exercises, stretching techniques, and myofascial release. Spinal manipulative therapy was defined as a manually performed manipulative procedure involving the application of a high-velocity, low-amplitude impulse at the end range of a spinal joint. Spinal mobilization was defined as a manually assisted spinal motion involving repetitive joint oscillations through varying ranges of motion without the application of a high-velocity, low-amplitude impulse. Flexion-distraction therapy was defined as a method of unloading spinal mobilization, which generally involves distractive traction components through flexion of the lumbar and hip joints in concert with superior manual pressure applied to the lumbar spine in a prone position. Myofascial release was defined as sustained or dynamic manual pressure applied to various soft tissue, either in a static state or while undergoing passive lengthening. Participants also received education about improving posture, stretching techniques, and ergonomic recommendations pertaining to their individual presentations. Chiropractic care was delivered by VA staff chiropractors with some contributions by supervised chiropractic residents and chiropractic students participating in a supervised clerkship.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics of mean, SD, and minimum and maximum values for age, BMI, baseline and outcome NRS values, baseline and outcome BBQ values, SC disability percentages, and SC values for the chief complaint were calculated for the sample using the statistics plug-in of Microsoft Excel. Two-tailed dependent t tests were used to compare before and after values of the outcome measures. The BBQ score was designated as our primary outcome, and using G*Power version 3.1.9.7, the minimum sample size for a matched t test of before and after BBQ scores was determined to be n = 34, assuming a power of 80%, an α value of 5%, and a target effect size of 0.5. In addition to statistical significance, clinical significance was assessed using a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of an average 30% or greater change between baseline and re-evaluation for both the NRS and BBQ. The MCID was based upon published accounts of an international consensus for a range of commonly used back pain outcome measures. [20, 23] The percentage of participants who reached or exceeded the MCID for the measures used were reported.

Results

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3 Of the 602 male veterans aged 65 to 89 years consulted for chronic LBP at the Buffalo VAMC chiropractic clinic over the 9–year time frame, 217 (36.1%) met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). For the purpose of this study, analyses were carried out for the sample (n = 217) with completed baseline and re-evaluation outcome measures for both the NRS and BBQ. The sample size of our study was substantial enough to confidently conclude that our statistical analyses were adequately powered.

Among the sample (n = 217), the mean age was 72.3 years. No participants were classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5), 23 (10.6%) were of normal weight (BMI of 18.5–24.9), 79 (36.4%) were overweight (BMI of 25–29.9), and the remaining 115 (53%) were obese (BMI > 30.0); the mean BMI of was 31.4 kg/m2. The mean SC disability percentage was 40.4%, and the mean SC relating to the chief complaint of LBP was 5.4%.

For BBQ scores, the mean change from baseline was 14.7 points (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.0–16.4; Figure 2), from a baseline score of 40.6 (95% CI, 39.0–42.3) to a discharge score of 25.9 (95% CI, 24.1–27.8), representing a percentage change from baseline of 35.9% (95% CI, 31.8%–40.0%; t = 16.7, P < .001). For NRS scores, the mean change from baseline was 2.2 points (95% CI, 1.8–2.5; Figure 3), from a baseline score of 6.0 (95% CI, 5.7–6.3) to a discharge score of 3.8 (95% CI, 3.5–4.1), representing a percentage change from baseline of 34.1% (95% CI, 29.1%–39.2%; t = 13.8, P < .001). The BBQ and NRS matched t test effect sizes of t were calculated to be 1.05 and 0.94, respectively. Based upon an established MCID of 30%, 57% of participants (n = 124) met or exceeded the MCID for the NRS and 58% (n = 126) for the BBQ. A total of 41% (n = 90) of participants met the MCID for both the NRS and BBQ.

Discussion

The results demonstrated clinically and statistically significant improvements in NRS and BBQ scores for this sample of older male veterans treated with chiropractic management for chronic LBP over a short course of 4 treatments. We chose to collect outcome measures after 4 treatments because we felt that this was around the time when information is needed to guide patient management within a course of care, in terms of both clinical response and resource allocation. The Nordic back pain subpopulation program demonstrated that early response to chiropractic treatment could be indicative of the overall response to care. In multiple studies, [17, 18] individuals who exhibited a favorable response to their initial chiropractic treatment were more likely to show clinical improvement of their LBP over the entirety of a treatment course. A favorable initial response to care is multifactorial and may include a combination of reduced pain severity, improved functionality, and minimal post-treatment adverse effects. Whereas a positive early response was predictive of overall clinical benefit, these findings were paralleled by a poor initial response predicting overall less treatment benefit. [17] Another study found that early recovery—that is, being LBP free at the fourth visit—was a strong predictor for being LBP free at 3 months and 12 months after care. [19] Based on these concepts, it is reasonable to assess outcomes early within a course of care in an attempt to optimize patient management resource allocation.

The findings of the present study should be considered within the context of a veteran-based population, which is majority older white men with multiple comorbid conditions. [24] The burden of illness among veteran ambulatory patients has been observed to be greater than twice that of ambulatory non-service members. [25] This notion of increased illness can be found within our study sample, as our average participant is an obese (BMI = 31.4) 72–year-old with >40% SC disability. These findings are clinically relevant because previous studies have shown that obesity is associated with a multitude of comorbid conditions and disability in the chronic LBP population. [26] Furthermore, severe comorbid conditions may decrease the likelihood of obtaining favorable results with traditional chiropractic care for LBP. [27, 28] Despite individual complexity from a high illness burden and potential barriers to positive outcomes, this sample of older male veterans had both clinically and statistically significant improvement in their chronic LBP with chiropractic management.

The results of this study are consistent with those of previous chart reviews performed in veteran populations receiving chiropractic management for musculoskeletal complaints with respect to improvements in pain severity ratings and functional outcome assessment scores. For example, a retrospective case series assessing clinical outcomes in U.S. veterans with LBP by Dunn et al [29] reported statistically significant improvement in NRS (37.4%) and BBQ (34.6%) scores. Additionally, a retrospective study of clinical outcomes for female veterans with LBP by Corcoran et al [30] reported a statistically significant reduction in BBQ scores (27.3%). Although there is evidence supporting the effectiveness of chiropractic care in treating musculoskeletal complaints in older adults [14–16] and additional studies examining chiropractic outcomes in veterans, [27–30] there remains limited evidence regarding clinical outcomes in older veterans treated with chiropractic care. It is important to note that treatment in this study was provided with a multimodal approach, and there is no way to allocate the effectiveness of individual treatment modalities applied. There may also be contributions from the nonspecific therapeutic effect of the patient encounter. This concept is substantiated by Dougherty et al, [11] who conducted a randomized controlled trial assessing the difference in clinical outcomes in older veterans with chronic lower back pain receiving either spinal manipulative therapy or a sham intervention. They found that both groups had similar favorable outcomes for pain relief and disability improvement, suggesting the presence of a beneficial nonspecific therapeutic effect from the clinical encounters.

Limitations

This study did not have a control group, and thus the lack of control for confounding variables may affect the results. Other limitations could include regional variations in our veteran population, clinical practice variations, and dependence on accurate data collection and clinical documentation, given that the data were obtained from a secondary data source. Furthermore, the status of chronic presentations (chronic stable vs acute on chronic) was not delineated and may have affected the clinical outcomes. Statistical analyses were based upon 217 participants, which represents a relatively small but adequately powered sample; however, the participants were from 1 location. Although treatments were generally provided at a frequency of once every 1 to 2 weeks, variations in the frequency of treatments and the duration of care may have occurred and may have influenced clinical outcomes. Many individuals were excluded due to the lack of discharge BBQ outcomes (373 of 602), representing patients who were lost to follow-up or discharged before a formal re-evaluation including updated BBQ was obtained. There are many potential factors that contribute to patients not completing a course of care as planned, which may have influenced our results. Moreover, the study was limited by the fact that outcomes were evaluated after the fifth visit, and the durability of improvements was not further investigated. Thus, our choice of 4 visits was arbitrary, and outcomes may have been different if a greater or lesser number of visits had been assessed. Additionally, the fact that our sample included only male veterans limits generalizability of the findings to female veterans. Last, the fact that the first response item for the BBQ is an NRS presents a confounding relationship between BBQ and NRS scores that was not controlled for in this study.

Future Studies

Further research is warranted and should be explored with a prospective randomized controlled design across multiple sites to inspect the efficacy of chiropractic care versus sham treatment within the older male veteran population with chronic lower back pain.

Conclusion

This retrospective review of a quality-assurance data set revealed clinically and statistically significant improvement in chronic LBP in terms of both numeric rating scale (NRS) and Back Bournemouth Questionnaire (BBQ) scores for this sample of older male U.S. veterans under chiropractic care.

Practical Applications

A short course of chiropractic care (4 visits) resulted in statistically and clinically significant improvement in lower back pain.

For this sample, chiropractic care was an effective treatment for chronic lower back pain in older men.

We found significant improvement in chronic lower back pain in terms of both numeric rating scale and Back Bournemouth Questionnaire scores.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

This research was not funded. It was carried out with resources of the Buffalo VA Medical Center. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government, or the VA Western New York Healthcare System's Chiropractic Residency Program.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): A.S.D., D.J.G.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): D.J.G.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): A.S.D., D.J.G.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): A.S.D., D.J.G.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): B.A.D., D.R.C.

Literature search (performed the literature search): B.A.D., D.J.G.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): B.A.D., A.S.D., D.J.G.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): B.A.D., A.S.D., D.J.G.

References:

Public health and aging: trends in aging—

United States and worldwide.

JAMA. 2003;289(11):1371–1373Colby SL, Ortman JM.

Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population:

2014 to 2060. Current Population Reports, P25-1143.

Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014.Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, et al.

The health status of elderly veteran enrollees in the Veterans Health Administration.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1271–1276Dionne CE, Dunn KM, Croft PR.

Does back pain prevalence really decrease with increasing age?

a systematic review.

Age Ageing. 2006;35(3):229–234Docking RE, Fleming J, Brayne C, et al.

Epidemiology of back pain in older adults:

prevalence and risk factors for back pain onset.

Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(9):1645–1653Scheele J, Enthoven WT, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al.

Characteristics of older patients with back pain in general practice:

BACE cohort study.

Eur J Pain. 2014;18(2):279–287alsbury SA, Vining RD, Hondras MA, et al.

Interprofessional attitudes and interdisciplinary practices for older

adults with back pain among doctors of chiropractic: a descriptive survey.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019;42(4):295–305Henschke N, Kamper SJ, Maher CG.

The epidemiology and economic consequences of pain.

Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(1):139–147Fatoye F, Wright JM, Gebrye T.

Cost-effectiveness of physiotherapeutic interventions for low back pain:

a systematic review.

Physiotherapy. 2020;108:98–107Bair MJ, Ang D, Wu J, et al.

Evaluation of stepped care for chronic pain (ESCAPE) in veterans of

the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: a randomized clinical trial.

JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):682–689Dougherty PE, Karuza J, Dunn AS, Savino D, Katz P.

Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic lower back pain in older veterans:

a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2014;5(4):154–164Kanodia AK, Legedza AT, Davis RB, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS.

Perceived Benefit of Complementary and Alternative Medicine

(CAM) for Back Pain: A National Survey

J Amer Board of Family Medicine 2010 (May); 23 (3): 354–62Nguyen HT, Grzywacz JG, Lang W, Walkup M, Arcury TA.

Effects of complementary therapy on health in a national U.S. sample of older adults.

J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(7):701–706Hondras MA, Long CR, Cao Y, et al.

A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing 2 Types of Spinal Manipulation

and Minimal Conservative Medical Care for Adults 55 Years and Older

With Subacute or Chronic Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Jun); 32 (5): 330–343Maiers M, Bronfort G, Evans R, Hartvigsen J, Svendsen K, Bracha Y, et al.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Exercise For Seniors

with Chronic Neck Pain

Spine J. 2014 (Sep 1); 14 (9): 1879–1889oulet JL, Kerns RD, Bair M, et al.

The musculoskeletal diagnosis cohort: examining pain and pain care among veterans.

Pain. 2016;157(8):1696–1703Axen I, Rosenbaum A, Robech R, Larsen K, Leboeuf-Yde C.

The Nordic Back Pain Subpopulation Program: Can Patient Reactions

to the First Chiropractic Treatment Predict Early Favorable

Treatment Outcome in Nonpersistent Low Back Pain?

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005 (Mar); 28 (3): 153–158Malmqvist S, LeBoeuf-Yde C, Ahola T, Andersson O, Ekström K, et al.

The Nordic Back Pain Subpopulation Program:

Predicting Outcome Among Chiropractic Patients in Finland

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2008 (Nov 7); 16: 13Leboeuf-Yde C, Gronstvedt A, Borge JA, Lothe J, Magnesen E. et al.

The Nordic Back Pain Subpopulation Program: Demographic and Clinical

Predictors for Outcome in Patients Receiving Chiropractic

Treatment for Persistent Low–Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004 (Oct); 27 (8): 493–502Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole MR.

Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity

measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale.

Pain. 2001;94(2):149–158Bolton JE, Breen AC.

The Bournemouth Questionnaire: A Short-form Comprehensive

Outcome Measure. I. Psychometric Properties in Back Pain Patients

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1999 (Oct); 22 (8): 503-510Public Office of, Affairs Intergovernmental.

US Department of Veterans Affairs; Washington, DC: 2015.

Federal Benefits for Veterans, Dependents and Survivors.Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, et al.

Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain:

towards international consensus regarding minimal important change.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(1):90–94National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics.

Congressional Briefing: Veteran Population Projection Model 2018Rogers WH, Kazis LE, Miller DR, et al.

Comparing the health status of VA and non-VA ambulatory patients:

the Veterans’ Health and Medical Outcomes Studies.

J Ambul Care Manage. 2004;27(3):249–262Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, Solovieva S, Viikari-Juntura E.

The association between obesity and low back pain: a meta-analysis.

Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(2):135–154Dunn AS, Passmore SR, Burke J, Chicoine D.

A Cross-sectional Analysis of Clinical Outcomes Following Chiropractic

Care in Veterans With and Without Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Military Medicine 2009 (Jun); 174 (6): 578–583Bronfort, G, Haas, M, Evans, R, Kawchuk, G, and Dagenais, S.

Evidence-informed Management of Chronic Low Back Pain

with Spinal Manipulation and Mobilization

Spine J. 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 213–225Dunn AS, Green BN, Formolo LR, Chicoine D.

Retrospective Case Series of Clinical Outcomes Associated With

Chiropractic Management For Veterans With Low Back Pain

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011; 48 (8): 927–934Corcoran KL, Dunn AS, Formolo LR, Beehler GP.

Chiropractic Management for US Female Veterans With Low Back Pain:

A Retrospective Study of Clinical Outcomes

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017 (Oct); 40 (8): 573–579

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 5-05-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |