Chiropractic Services and Diagnoses for Low Back

Pain in 3 U.S. Department of Defense Military

Treatment Facilities: A Secondary Analysis

of a Pragmatic Clinical TrialThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2021 (Nov); 44 (9): 690–698 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Anna-Marie L. Ziegler, MM, DC, Zacariah Shannon, DC, MS, Cynthia R. Long, PhD, Joan A. Walter, JD, PA, Ian D. Coulter, PhD, Christine M. Goertz, DC, PhD

Palmer Center for Chiropractic Research,

Palmer College of Chiropractic,

Davenport, Iowa.

Thanks to JMPT for permission to reproduce this Open Access article!

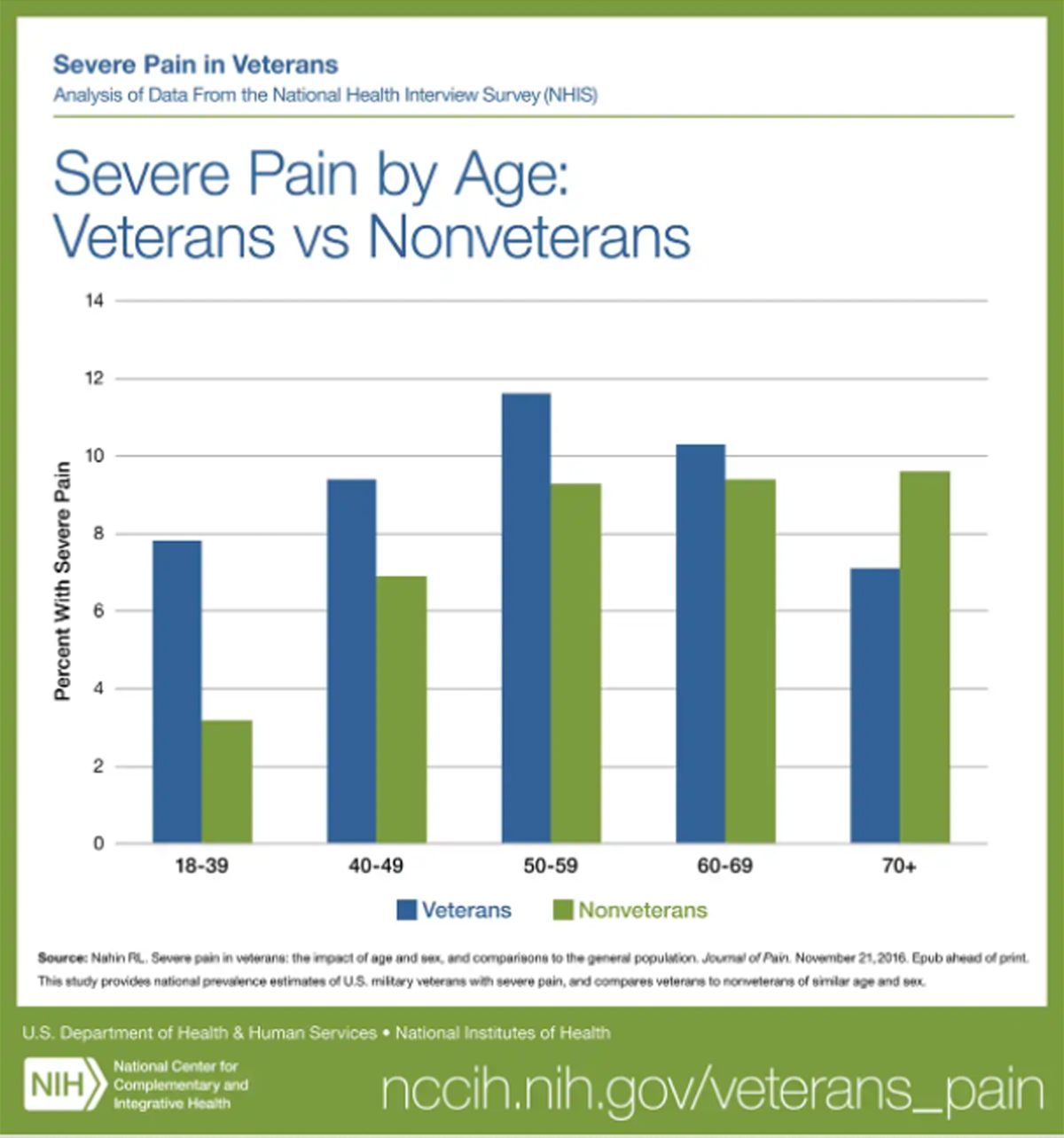

FROM: Nahin ~ Pain 2017

Objective: The purpose of this study was to describe the diagnoses and chiropractic services performed by doctors of chiropractic operating within 3 military treatment facilities for patients with low back pain (LBP).

Methods: This was a descriptive secondary analysis of a pragmatic clinical trial comparing usual medical care (UMC) plus chiropractic care to UMC alone for U.S. active-duty military personnel with LBP. Participants who were allocated to receive UMC plus 6 weeks of chiropractic care and who attended at least 1 chiropractic visit (n = 350; 1,547 unique visits) were included in this analysis. International Classification of Diseases and Current Procedural Terminology codes were transcribed from chiropractic treatment paper forms. The number of participants receiving each diagnosis and service and the number of each service on unique visits was tabulated. Low back pain and co-occurring diagnoses were grouped into neuropathic, nociceptive, bone and/or joint, general pain, and nonallopathic lesions categories. Services were categorized as evaluation, active interventions, and passive interventions.

Results: The most reported pain diagnoses were lumbalgia (66.1%) and thoracic pain (6.6%). Most reported neuropathic pain diagnoses were sciatica (4.9%) and lumbosacral neuritis or radiculitis (2.9%). For the nociceptive pain, low back sprain and/or strain (15.8%) and lumbar facet syndrome (9.2%) were most common. Most reported diagnoses in the bone and/or joint category were intervertebral disc degeneration (8.6%) and spondylosis (6.0%). Tobacco use disorder (5.7%) was the most common in the other category. Chiropractic care was compromised of passive interventions (94%), with spinal manipulative therapy being the most common, active interventions (77%), with therapeutic exercise being most common, and a combination of passive and active interventions (72%).

Conclusion: For the sample in this study, doctors of chiropractic within 3 military treatment facilities diagnosed, managed, and provided clinical evaluations for a range of LBP conditions. Although spinal manipulation was the most commonly used modality, chiropractic care included a multimodal approach, comprising of both active and passive interventions a majority of the time.

Keywords: Chiropractic; Current Procedural Terminology; International Classification of Diseases; Manipulation, Spinal; Military Personnel.

Trial Registry: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01692275.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

A key mission of the U.S. Military Health System and its treatment facilities is supporting readiness of military service personnel. [1] Low back pain (LBP) is a leading cause of disability worldwide [2] and is highly prevalent in military populations. [3–6] It is among the most common conditions interrupting combat duty. [7–9] A frequent reason for seeking medical care, [6, 10] LBP accounted for approximately 6.2 million medical encounters in the U.S. active-duty military population between 2010 to 2014. [10] Low back pain places military personnel at an increased risk of medical discharge. [7, 8, 10]

Recent guidelines emphasize nonpharmacological and nonsurgical treatments for LBP. [11–14] Doctors of Chiropractic (DCs) commonly use multimodal approaches, including a variety of guideline-recommended nonpharmacological treatments such as spinal manipulation. [15] Multimodal chiropractic care has been described as including 1 or more of the following: education about a health condition; passive interventions, such as spinal manipulation; transitional interventions, such as therapeutic exercise; active interventions, such as general exercise; and self-management advice to monitor and control symptoms. [16]

Chiropractic care was originally integrated into 10 military treatment facilities (MTFs) in 1995. [17–20] By 2015, 60 MTFs offered chiropractic care, with a primary focus on chronic pain and back pain. [21, 22] Although the integration of chiropractic services within MTFs has grown since inception, [20] little is known about chiropractic care delivery within U.S. military healthcare settings. A systematic review studying chiropractic integration in military healthcare facilities published in 2016 and a scoping review of chiropractic services in active-duty military settings published in 2019 noted limited data are available and concluded there is a need for further descriptive data informing the role of chiropractic services in active duty military. [9, 17] Such knowledge is important to understand how chiropractic is implemented within military healthcare and can be used to inform decisions about ongoing integration and future military health workforce planning.

Previous studies have focused on prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use, reasons for use, healthcare utilization patterns, and self-reported symptoms of active-duty military personnel utilizing complementary and alternative medicine services. [23–27] Detailed information on the particular features of chiropractic care within MTFs is limited. Within MTFs, chiropractors serve as members of interprofessional teams collaboratively working with other healthcare professionals. [19] Personnel receive care in the context of medical care plus chiropractic care in an integrated setting. Understanding delivery of chiropractic care within such a context is important for informing future integration and health policy. Few studies have described in detail the types of diagnoses or services performed in MTFs. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe chiropractic services and diagnoses at 3 geographically distinct MTFs for active-duty United States military personnel with LBP.

Methods

This secondary analysis of data was collected by personnel in the chiropractic clinics during a pragmatic, parallel-group clinical trial for U.S. active-duty military service members experiencing LBP who were allocated to the UMC plus chiropractic care group. A detailed trial protocol [28] and primary outcomes have been published elsewhere. [29] The trial was approved by institutional review boards at Palmer College of Chiropractic, the RAND Corporation, and at each military site and was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring committee. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01692275). All participants provided written informed consent.

Settings and Participants

Participants were enrolled between September 28, 2012, and November 20, 2015, at the following 3 MTFs:(1) Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland;

(2) Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, California; and

(3) Naval Hospital Pensacola, Pensacola, Florida.Participants either self-referred through posted advertisements or were referred by primary care providers. Participants were eligible if they were active-duty military personnel aged 18 to 50 years with musculoskeletal-related LBP of any duration. The presence of conditions considered to be contraindications to spinal manipulation, such as recent spinal fracture or spinal surgery, or severe radiculopathy requiring further diagnostic evaluation or referral, were exclusionary. Knowledge of a pending absence or transfer during the active phase of the trial and spinal manipulative care within the previous month were also exclusionary. Screening examinations to assess eligibility were conducted by medical physicians or independent duty corpsmen. As previously reported, 750 participants were allocated to receive UMC plus chiropractic care or UMC alone. [29] Of the 375 allocated to receive UMC plus chiropractic care, the participants who attended at least 1 chiropractic visit were included in this secondary analysis.

Intervention

Trial participants were allocated to receive either UMC alone or UMC plus chiropractic care for 6 weeks. Usual medical care consisted of any care recommended or prescribed to treat LBP by non-chiropractic military clinicians, which could include a focused history and physical examination, pharmacologic pain management, education about a condition, and self-management advice. Types of UMC also included referrals to physical therapy, pain clinic, and physical therapy and pain management clinic. [28, 29] Those participants allocated to receive chiropractic care in addition to UMC were able to have up to 12 chiropractic visits during a 6–week active care period. Chiropractic care for LBP was delivered pragmatically by trial DCs, meaning clinicians were free to use their clinical judgment regarding examination, diagnosis, or treatment protocols. [29] Trial DCs had 15 to 20 years of experience delivering care within the MTF prior to initiation of the study. Participants received care from a single DC at Naval Hospital Pensacola, 1 DC at Naval Medical Center San Diego, and 2 DCs provided care at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. [28]

Diagnoses and services data for each participant allocated to UMC plus chiropractic care were collected from the DC or a scribe using a standardized paper form at each chiropractic visit. The 1–page form contained a preselected and commonly used subset of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, as well as space to write additional ICD or CPT code(s) as needed. Codes pertained to both low back pain and co-occurring conditions. The data collection form is in the protocol that is available in Supplement 1 of the primary paper. [29] Trial personnel transcribed data from the paper forms into an electronic form housed within the Submission Tracking and Reporting System, a custom web-based application developed by the Palmer Center for Chiropractic Research. Paper forms were then deidentified, and a dataset was generated for descriptive analysis.

Analysis

Two authors (A.Z. and Z.S.) used a consensus process to group similar diagnoses and services. Both authors are DCs enrolled in graduate research training programs. Codes indicating the same service or general diagnosis but applied to a different bodily region were combined into a single descriptor representing all similar codes. For instance, codes for spinal manipulative therapy applied to differing numbers of regions were combined into the singular descriptor, spinal manipulative therapy. SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used to tabulate the number of participants receiving each diagnosis and service, as well as the number of each service on unique chiropractic visits.

Diagnoses were categorized consistent with terminology and definitions established by the International Association for the Study of Pain. [30] The neuropathic pain category included diagnoses consistent with the following definition: pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. [30] The nociceptive pain category included diagnoses consistent with the following definition: pain that arises from actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissue and is due to the activation of nociceptors. [30] Other diagnoses were organized as general pain, bone and/or joint conditions, or nonallopathic lesions. The general pain category included diagnoses indicating regional pain without differentiating an underlying pain source (eg, lumbalgia). The bone and/or joint category categorized diagnoses indicating a postural or imaging finding (eg, spondylosis). We sorted services into clinical evaluation and active and passive intervention categories (eg, electrical muscle stimulation). Active interventions were those participants controlled or performed, such as therapeutic exercise; passive interventions were those performed by the DC, such as spinal manipulation. [16]

Results

Participants

Table 1 Of the 375 participants allocated to receive UMC plus chiropractic care, 350 attended at least 1 chiropractic visit. The mean participant age was 31.1 years (Table 1). Twenty-three percent were female participants, 49 (14%) were of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, and 112 (32%) were non-White. Fifty-one percent of participants had experienced LBP for more than 3 months. Fifty percent of participants were Navy personnel.

Diagnoses

Table 2 Diagnoses were collected for 348 of the 350 participants (Table 2). The most reported diagnoses were lumbalgia (230, 66.1%) and thoracic pain (23, 6.6%), both in the general pain category. Most commonly reported neuropathic pain diagnoses were sciatica (17, 4.9%) and lumbosacral neuritis or radiculitis (10, 2.9%). For the nociceptive pain category, low back sprain and/or strain (55, 15.8%) and lumbar facet syndrome (32, 9.2%) were most common. Most commonly reported diagnoses in the bone and/or joint category were intervertebral disc degeneration (30, 8.6%) and spondylosis (21, 6.0%). Tobacco use disorder (20, 5.7%) was most common in the other category. Most reported nonallopathic lesions were of the cervical region (17, 4.9%) and sacral region (17, 4.9%).

Services

Table 3

Table 4 Table 3 displays clinical evaluation services. Detailed new patient evaluations occurred with 165 (47.1%) participants. Problem-focused established patient evaluations occurred on 256 (17.1%) visits. Diagnostic radiology of the lumbar spine occurred with only 1 participant (0.3%) on a single visit (0.1%). On visit 1, 287 (82%) new patient exams and 26 (7.4%) established patient exams were recorded. The remaining 37 initial chiropractic visits were not coded as evaluations.

Chiropractic care was received by 350 participants over 1547 unique visits (Table 4). Passive interventions were provided to 329 (94.0%) participants. Spinal manipulative therapy, the most common passive intervention, was used, with 325 (92.9%) participants over 1350 (87.3%) visits. Active interventions were employed with 271 (77.4%) participants. Therapeutic exercise was most common, reported for 173 participants over 207 (13.4%) visits. A combination of passive and active services was provided to 251 (71.7%) participants.

Discussion

This secondary analysis is the first study we are aware of providing a detailed description of chiropractic care for active-duty personnel with LBP within the integrative setting of MTFs. The randomized clinical trial from which these data were obtained was the first large-scale clinical trial investigating chiropractic care in addition to UMC in this integrative setting,9,29 which provides opportunity for examining chiropractic care in this emerging context. Previous studies report broad health service overviews of chiropractic care within the U.S. Department of Defense health system.9,17 A 2016 study used electronic health record data to describe common diagnoses and services used by DCs in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration.31 Only regional conditions were reported (eg, LBP, neck pain), providing less detail than our descriptive report. Also, military veterans comprise the patient population within the Veterans Health Administration and thus are not directly comparable to the active-duty personnel within MTFs. Although diagnoses demonstrated co-occurring complaints and/or conditions extending beyond LBP for some of our trial participants, all were receiving chiropractic care for LBP in the context of a pragmatic clinical trial.

At the trial MTFs, service members accessed chiropractic care through a primary care provider who performed an initial clinical evaluation and acted as gatekeeper.9,18 Because participants received eligibility exams from primary care providers or independent duty corpsmen, health system characteristics, such as the existence of gatekeepers, likely influenced chiropractic services. Though DCs possessed imaging ordering privileges, we only noted a single order for imaging in this study. In comparison, according to a national survey of U.S. DCs, 56% of chiropractic patients receive imaging when radiography is available in a chiropractor's office and 22% when imaging is available only through an outside facility.15 Although referring provider data were not available, some participants likely received imaging prior to chiropractic referral. Because imaging, when performed, likely occurred prior to initial chiropractic evaluation, we expected few additional imaging orders. The presence of diagnoses describing radiographic findings (eg, intervertebral disc degeneration) supports this interpretation. Although 350 participants received chiropractic services, 287 initial visits were coded as new patient evaluations. Trial eligibility criteria allowed established patients to participate if they had not received care within the past month.

Musculoskeletal care guidelines recommend providing patients with education and/or information about their condition, including management options.13 Education can help patients understand their condition and gain self-management skills. It can also lead to decreased healthcare utilization, improved quality of life, reduced pain-related distress through reassurance, and increased confidence in personal ability to cope.32, 33, 34 Although recommended for musculoskeletal conditions, such as LBP, and reported as a common treatment provided by DCs,35 education was not reported as an intervention in this study. Current Procedural Terminology codes aligning with patient education and self-management require 30 minutes face-to-face contact either with a physician or as prescribed but performed by another trained healthcare professional.36 Thirty minutes of dedicated education time did not likely fit within the timeframe of scheduled office visits at participating MTFs. In addition, patient education (CPT codes 98960-2) codes are not reimbursable in MTFs, posing an additional barrier to their use.37,38 As a result, CPT codes are likely not an adequate means of assessing patient education delivered as a part of chiropractic care.

Due to the multicomponent nature of LBP and the absence of gold standard tests, definitively diagnosing a single source of LBP is often unrealistic.39,40 This concept aligns with the common occurrence of non-descript diagnoses, such as lumbalgia (66.1% of participants). The presence of a wide range of diagnoses also suggests practitioners considered other factors as clinically important. For multicomponent LBP, diagnoses can be chosen to describe a general problem (eg, lumbalgia), a specific condition influencing management (eg, radiculitis), or other potentially contributing factors (eg, tobacco use disorder). Because there are no specific guidelines for choosing or prioritizing diagnoses, inferring the clinical thinking behind those collected is beyond the scope of this study.

Most participants received spinal manipulative therapy, and many received other passive interventions. Active interventions promote functional improvement as a treatment goal, as well as potentially and positively impacting symptoms, strength, motor control, and psychological factors, such as self-efficacy.16,41,42 Over 75% of trial participants received an active intervention, and 72% received both passive and active interventions. These data show participating DCs often used both passive and active interventions when managing LBP.

Limitations

Describing chiropractic care through diagnosis and CPT codes has several limitations. One CPT code can be used to describe multiple services. For example, “neuromuscular re-education” (CPT code 97112) could describe proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, Feldenkreis, or other unnamed exercises focused on neuromuscular retraining. Codes pertaining to chiropractic manipulative therapy describe the number of regions but do not specify which region. As a result, this study is not able to identify which body regions where chiropractic manipulative therapy was applied.

The data collection form did not link specific services with individual diagnoses, so further investigation of this relationship was not possible. Also, as a secondary analysis of a single pragmatic clinical trial involving participants with LBP conducted at 3 U.S. MTFs, findings may not represent chiropractic care for other conditions or at other U.S. MTFs.

Conclusion

The DCs at 3 MTFs rendering care for active-duty participants within the context of a pragmatic clinical trial evaluated, diagnosed, and managed a range of LBP conditions. Chiropractic care was most often employed using a multimodal approach. Most patients received spinal manipulative therapy, and more than 70% received a combination of both passive and active interventions.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

The original study from which these data were obtained was funded by the Department of Defense Office of Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, Defense Health Program Chiropractic Clinical Trial Award (W81XWH-11-2-0107). Dr. Ziegler reports grants from NCMIC Foundation and NIH/NCCIH outside of the submitted work. Dr. Vining reports grants from the Department of Defense Office of Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs and the Defense Health Program Chiropractic Clinical Trial Award (W81XWH-11-2-0107) during the conduct of the study. Dr. Long reports grants from the Defense Health Program Chiropractic Clinical Trial Award during the conduct of the study. Dr. Walter reports grants from the RAND Corporation during the conduct of the study. Dr. Goertz reports personal fees from The Spine Institute for Quality, the Palmer College of Chiropractic, and the American Chiropractic Association outside of the submitted work.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): C.G., R.V. Design (planned the methods to generate the results): A.Z., C.L., Z.S.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): C.L., R.V.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): A.Z., Z.S., C.L.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): A.Z., Z.S., C.L., R.V.

Literature search (performed the literature search): A.Z. Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): A.Z., R.V., C.L.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): A.Z., Z.S., C.L., R.V., I.C., J.W., C.G.

References:

Military Health System.

About the Military Health System. Available at:

https://health.mil/About-MHS

Accessed October 14, 2021.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators

James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, et al.

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability

for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017:

a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.

Lancet 2018;392:1789–858GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability

for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the

Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.

Lancet 2016;388:1545–602Fatoye F Gebrye T Odeyemi I.

Real-world incidence and prevalence of low back pain using routinely collected data.

Rheumatol Int. 2019; 39: 619-626Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, Buchbinder R.

The epidemiology of low back pain.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:769–781Bader CE Giordano NA McDonald CC Meghani SH Polomano RC.

Musculoskeletal pain and headache in the active duty military population:

an integrative review.

Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2018; 15: 264-271Benedict TM Singleton MD Nitz AJ Shing TL Kardouni JR.

Effect of chronic low back pain and post-traumatic stress disorder

on the risk for separation from the US Army.

Mil Med. 2019; 184: 431-439Cohen SP Gallagher RM Davis SA Griffith SR Carragee EJ.

Spine-area pain in military personnel: a review of epidemiology,

etiology, diagnosis, and treatment.

Spine J. 2012; 12: 833-842Mior S Sutton D Cancelliere C et al.

Chiropractic Services in the Active Duty Military Setting:

A Scoping Review

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2019 (Jul 15); 27: 45Clark LL Hu Z.

Diagnoses of low back pain, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2010-2014

A Comparative Effectiveness Clinical Trial

Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR) 2015 (Dec); 22 (12): 8–11Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, et al.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review

for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 493–505Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, Goucke R, Nagree Y, Gibberd M, et al.

What Does Best Practice Care for Musculoskeletal Pain Look Like?

Eleven Consistent Recommendations From High-quality

Clinical Practice Guidelines: Systematic Review

British J Sports Medicine 2020 (Jan); 54 (2): 79–86The Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain Work Group.

VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain

Washington, DC: The Office of Quality, Safety and Value, VA, &

Office of Evidence Based Practice, U.S. Army MedicalCommand, 2017, Version 2.0.Himelfarb I Hyland J Ouzts N et al.

Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2020

A Project Report, Survey Analysis, and Summary of the Practice

of Chiropractic Within the United States.

National Board of Chiropractic Examiners,

Greeley, Colorado 2020Vining RD, Shannon ZK, Salsbury SA, Corber L, Minkalis AL, Goertz CM.

Development of a Clinical Decision Aid for Chiropractic Management of

Common Conditions Causing Low Back Pain in Veterans:

Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 677–693Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ.

Integration of Chiropractic Services in Military and Veteran Health Care Facilities:

A Systematic Review of the Literature

J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016 (Apr); 21 (2): 115–130Dunn AS, Green BN, Gilford S.

An Analysis of the Integration of Chiropractic Services Within

the United States Military and Veterans' Health Care Systems

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 749–757Green BN Dunn AS.

An Essential Guide to Chiropractic in the United States

Military Health System and Veterans Health Administration

J Chiropractic Humanities 2021 (Dec 22_; 28: 35–48Green BN, Gilford SR, Beacham RF.

Chiropractic in the United States Military Health System:

A 25th-Anniversary Celebration of the Early Years

J Chiropractic Humanities 2020 (Dec); 27: 37-58Herman PM, Sorbero ME, Sims-Columbia AC.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Services in the Military Health System

J Altern Complement Med. 2017 (Nov); 23 (11): 837–843Williams V, Clark L, McNellis M.

Use of Complementary Health Approaches at Military Treatment Facilities,

Active Component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2010-2015

Medical Surveillance Monthly Report (MSMR) 2016 (Jul); 23 (7): 9–22George S, Jackson JL, Passamonti M.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine in a Military Primary Care Clinic:

A 5-year Cohort Study

Military Medicine 2011 (Jun); 176 (6): 685–688Goertz, C, Marriott, BP, Finch, MD et al.

Military Report More Complementary and Alternative

Medicine Use Than Civilians

J Altern Complement Med. 2013 (Jun); 19 (6): 509–517Jacobson EE Meleger AL Bonato P et al.

Structural integration as an adjunct to outpatient rehabilitation for

chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized pilot clinical trial.

Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015; 2015813428Reinhard MJ Nassif TH Bloeser K et al.

CAM utilization among OEF/OIF veterans: findings from the

National Health Study for a New Generation of US Veterans.

Med Care. 2014; 52: S45-S49White MR Jacobson IG Smith B et al.

Health care utilization among complementary and alternative

medicine users in a large military cohort.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011; 11: 27Christine M. Goertz, Cynthia R. Long, Robert D. Vining, Katherine A. Pohlman,

Bridget Kane, Lance Corber, Joan Walter, and Ian Coulter

Assessment of Chiropractic Treatment for Active Duty, U.S. Military Personnel

with Low Back Pain: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial

Trials. 2016 (Feb 9); 17 (1): 70Goertz CM, Long CR, Vining RD, Pohlman KA, Walter J, Coulter I.

Effect of Usual Medical Care Plus Chiropractic Care vs Usual Medical Care

Alone on Pain and Disability Among US Service Members With

Low Back Pain. A Comparative Effectiveness Clinical Trial

JAMA Network Open. 2018 (May 18); 1 (1): e180105 NCT01692275International Association for the Study of Pain.

IASP Terminology. Available at:

https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=

1698&navItemNumber=576#Sensitization

Accessed November 8, 2019.Lisi AJ, Brandt CA.

Trends in the Use and Characteristics of Chiropractic Services

in the Department of Veterans Affairs

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jun); 39 (5): 381–386Stenberg U Vågan A Flink M et al.

Health economic evaluations of patient education interventions

a scoping review of the literature.

Patient Educ Couns. 2018; 101: 1006-1035Stenberg U Haaland-Øverby M Fredriksen K Westermann KF Kvisvik T.

A scoping review of the literature on benefits and challenges of participating

in patient education programs aimed at promoting self-management for

people living with chronic illness.

Patient Educ Couns. 2016; 99: 1759-1771Traeger AC Hübscher M Henschke N Moseley GL Lee H McAuley JH.

Effect of primary care–based education on reassurance in patients with

acute low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175: 733-743Beliveau PJH, Wong JJ, Sutton DA, Simon NB, Bussieres AE, Mior SA, et al.

The Chiropractic Profession: A Scoping Review of Utilization Rates,

Reasons for Seeking Care, Patient Profiles, and Care Provided

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Nov 22); 25: 35American Medical Association.

Current Procedural Terminology: CPT: 2015.

Vol Professional edition.

Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=

true&db=nlebk&AN=847039&site=ehost-live

Accessed October 25, 2021.Military Health System.

TRICARE Policy Manual 6010.57-M Chap 7 Sect 16.4. Available at:

https://manuals.health.mil/pages/DisplayManualFile.aspx?Manual=

TP08&Date=2015-01-22&Type=AsOf&Filename=C7S16_4.PDF

Accessed October 25, 2021.Military Health System.

No Government Pay Procedure Code List.

Military Health System. Available at:

https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/

TRICARE-Health-Plan/Rates-and-Reimbursement/No-Government-Pay-Procedure-Code-List

Accessed October 25, 2021.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, Hoy D, Karppinen J et al.

What Low Back Pain Is and Why We Need to Pay Attention

Lancet. 2018 (Jun 9); 391 (10137): 2356–2367

This is the first of 3 articles in the remarkable Lancet Series on Low Back PainVining RD, Minkalis AL, Shannon ZK, Twist EJ.

Development of an Evidence-Based Practical Diagnostic Checklist

and Corresponding Clinical Exam for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 665-676Cosio D Lin E.

Role of active versus passive complementary and

integrative health approaches in pain management.

Glob Adv Health Med. 2018; 72164956118768492Du S Hu L Dong J et al.

Self-management program for chronic low back pain:

a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Patient Educ Couns. 2017; 100: 37-49

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 7-07-2022

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |