Chiropractic in the United States Military Health System:

A 25th-Anniversary Celebration of the Early YearsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Chiropractic Humanities 2020 (Dec); 27: 37-58 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Bart N.Green DC, MSEd, PhD, Scott R.Gilford DC, Richard F.BeachamDC

Employer Based Integrated Primary Care Health Centers,

Stanford Health Care,

San Diego, California

Objective The purpose of this report is to record noteworthy events that occurred during the early years of chiropractic in the United States Military Health System (MHS).

Methods We used mixed methods to create this historical account, including documents, artifacts, research papers, and reports from personal experiences.

Results Chiropractic care was first included in the MHS in 1995, after years of legislative activity. The initial program was a 3-year study of the feasibility and advisability of integrating chiropractic in the MHS. This period was called the Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Project; 20 pioneering chiropractors began their MHS journeys at 10 military bases in fiscal year 1995. The Demonstration Project was extended for 2 more years to gather research data, and 3 additional military facilities were added during those years to accomplish that purpose. The Demonstration Project concluded in 1999. In 2000, Congress approved the development of permanent chiropractic services and benefits for members of the uniformed services. These new clinics opened in 2002.

There is more like this at our

CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS PageConclusion This is the first article to chronicle the history of chiropractic in the MHS, and highlights some of the important events in the early years of chiropractors working within the MHS. Because of the efforts of the early MHS chiropractors to pave the way for a permanent chiropractic benefit for the deserving members of the United States uniformed services, chiropractic care is now offered at more than 60 United States military facilities.

Key Indexing Terms Chiropractic, Military Health Services, History, Hospitals, Military

From the FULL TEXT :

INTRODUCTION

Chiropractic is a licensed health care profession in most world regions. The greatest number of doctors of chiropractic (DCs) are in the United States, where there are approximately 77,000 practitioners. [1] Patients have direct access to chiropractic care, meaning that no referral is necessary from another provider for a patient to receive chiropractic care. Thus, most chiropractors operate at the primary level of health care, where they work with other health care professionals. [2] Problems of the neuromusculoskeletal system are the most common conditions seen by chiropractors. [2] However, chiropractors do not merely focus on the biomechanical aspects of human health. Psychological, social, and environmental relationships present in the biopsychosocial model of care are also a mainstay of practice and philosophy. [3]

Doctors of chiropractic have humbly served the men and women of the United States military by providing chiropractic care in the Military Health System (MHS) for 25 years. Chiropractors are independent licensed practitioners for all 3 branches of the military (Army, Navy, Air Force). Presently, chiropractors are civilian providers of chiropractic care to members of the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Public Health Service, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In some special cases, chiropractors provide care for civilians, including national leaders and politicians at the US capitol. [4]

Doctors of chiropractic are credentialed at the headquarters (ie, command) of the military facility where they work and are granted hospital privileges at the health care facilities associated with that command. Chiropractors receive basic (ie, core) privileges at their commands, including permission to perform essential functions as chiropractors in the MHS. Core privileges include procedures such as joint manipulation and other chiropractic techniques, soft tissue techniques, therapeutic exercise, and the use of physiotherapeutic modalities. They also include ordering axial skeletal radiography and standard laboratory tests and assigning service members to quarters or limited light duty. [5] Upon evidence of proper training and proficiency, chiropractors may be granted supplementary privileges, such as ordering advanced diagnostic imaging, additional laboratory tests, and electromyography and nerve conduction velocity studies. [6]

At many MHS locations, patients have direct access to chiropractic care. Chiropractors are often the first provider to care for patients’ musculoskeletal concerns. Chiropractors at all military treatment facilities (MTFs) receive referrals from other professionals. They may be integrated into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of care, serving on interprofessional teams. According to the MHS health care administrator TRICARE, there are 60 locations where doctors of chiropractic provide care in the continental United States, 3 in Germany, and 1 in Japan. [7] However, some commands offer several locations for chiropractic services, and not all clinics are listed on the TRICARE website. [8] Chiropractors are located at hospitals, special forces commands, air stations, submarine stations, infantry training schools, combat casualty care centers, chronic pain clinics, sports medicine clinics, and other environments. [8]

However, chiropractors have not always had the opportunity to provide their services in these positions. In fact, chiropractic care was not available at military facilities until 1995, and the locations that offered chiropractic services were limited compared to today’s MTF offerings. The early chiropractors in the MHS were pioneers who stepped onto uncharted grounds, endured considerable struggles, and received deserved accolades. Despite a proud legacy and continuing presence in the MHS, the history of chiropractic in the MHS has never been told. The purpose of this article is to record and highlight some of the noteworthy events of the first years of chiropractic in the MHS.

METHODS

This is a sociopolitical history that focuses on the development of government policies and the history of the people affected by them. [9] We constructed this report by integrating several sources of information. Government documents were retrieved from open sources. Notes from minutes of key meetings were obtained from meeting attendees. We reviewed personal correspondence with various individuals. We also reviewed our personal collections of photos and other memorabilia for content and asked other chiropractors to contribute additional artifacts. Two prior reviews of the literature on chiropractic care for military and veteran service members provided the bulk of the peer-reviewed evidence for this review. [10, 11]

Because we desired to create a richness to this historical account, we intentionally infused our experiences from our time with the MHS as examples. Our perspective is that we were involved with the MHS between the years 1993 and 2019, with a combined 56 years of MHS experience. Because this is a historical article written by chiropractors who lived it, we have used both first- and third-person perspectives throughout.

We elected to focus on 3 distinct phases of the introduction of chiropractic into the MHS. The initial phase included events leading up to the Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Project. The next phase was a 5-year trial, the Demonstration Project, with no degree of certainty that chiropractic services would continue. The last phase of 5 years represents when the US government determined that chiropractic would be a permanent benefit for US uniformed services, based on the success of the first 5 years. Further expansions of the benefit came several years later.

Figure 1 Our experiences also represent 3 waves of chiropractor contributions in the evolution of chiropractic in the MHS over the period of study. Richard Beacham represents before the program started, the planning and oversight, and then as a provider in the permanent-benefit phase. Scott Gilford was 1 of the first chiropractors in the MHS and served for nearly 25 years, representing both the Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Project and the permanentbenefit phases. Bart Green was 1 of the early chiropractors in the permanent-benefit phase. Each of our perspectives provides a slightly different interpretation of the events during the growth of chiropractic in the MHS (Figure 1).

RESULTS

Before the Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Project

Several pieces of legislation led to the eventual placement of chiropractors in military facilities. [8] Two of these acts caused military leaders to become aware that further legislation pertaining to the inclusion of chiropractors in the MHS was forthcoming (letter from Richard Beacham to Congressman John Kyl, June 21, 1993). In the Department of Defense Authorization Act of 1985, Congress directed the secretary of defense to conduct a study to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of chiropractic. [12] This was followed by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993, which allowed the US military to appoint chiropractors as commissioned officers. [13]

The early 1990s were times of cultural change in health care that reduced barriers for chiropractors to join collaborative health care teams. In 1987, the American Hospital Association had finally changed its antichiropractic stance to allow hospitals to grant privileges to doctors of chiropractic. [14] In 1988, a judge’s decision had resulted in an injunction clarifying that the American Medical Association could no longer impede medical doctors from collaborating with chiropractors. [15] These actions created opportunities for chiropractors to provide services where they were not allowed before. Up to this point in time, no chiropractic care had been included in hospitals or in health services for the military. Further lobbying and legislation would be needed, in addition to someone who could understand and communicate in the different worlds of chiropractic and the military.

Richard Beacham, DC, became a key figure in the development of MHS chiropractic services. He understood both chiropractic and military culture and customs, having simultaneously been a chiropractor and a naval officer. He possessed extensive experience as a naval aviator, including 3 combat cruises in Vietnam and 2 flight instructor tours. He served in the Naval Reserve for 15 years after 11 years of active duty, retiring as a captain. During his years in the Naval Reserve, he was a practicing chiropractor, chiropractic college clinical professor, and college administrator. His role in the birthing process of chiropractic in the military was crucial.

Beacham’s involvement in military chiropractic affairs began with an introduction to Arlan Fuhr, DC, also a Navy veteran and a coinventor of the Activator adjusting instrument. 16 They were introduced to each other by a mutual friend, Bernard Coyle, MA, PhD (letter from Richard Beacham to Arlan Fuhr, April 14, 1993). At that time, Fuhr served as the treasurer for the election campaign of Congressman John Kyl, cochairman of the Military Personnel Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee. Beacham and Fuhr corresponded in April 1993 about the possibility of the MHS adding chiropractic to its range of services, and Beacham shared his desire to be involved in the process (letter from Richard Beacham to Arlan Fuhr, April 14, 1993). Additional activities to introduce chiropractic into the MHS were occurring in the office of Senator Strom Thurmond. Beacham was thereafter asked to visit the Pentagon. On June 17, 1993, Beacham engaged in preliminary conversations about how chiropractic might be introduced into the MHS with Rear Admiral Edward Martin, MD (letter from Richard Beacham to Edward Martin, June 21, 1993), the acting assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, and Congressman Kyl (letter from Richard Beacham to Congressman John Kyl, June 21, 1993).

Behind the scenes, lobbyists and officers of organizations, politicians, and military leaders were having discussions about what might be the future of chiropractors in the MHS. However, there is little information available to describe who was involved or what activities transpired. Although activities about chiropractic care for military members were occurring, whether it would become reality was not yet known.

The Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Project

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1995 was passed during the 103rd Congress on January 25, 1994. This act announced publicly that the military would include chiropractic in the MHS, at least temporarily. A section of the act introduced by Senator Thurmond from South Carolina and lobbied for by the American Chiropractic Association [17] directed that the Department of Defense was to establish a 3-year trial project at no fewer than 10 MTFs, starting in 1995, to assess the feasibility and advisability of integrating chiropractic care in the MHS. [18] This became known as the Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Project (CHCDP) . The first paragraph of section 731 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1995, designating the CHCDP, stated:SEC 731. CHIROPRACTIC HEALTHCARE DEMONSTRATION PROGRAM.

(a) Requirement for Program. – (1) Not later than 120 days after the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary of Defense shall develop and carry out a demonstration program to evaluate the feasibility and advisability of furnishing chiropractic care through the medical care facilities of the Armed Forces. The Secretary of Defense shall develop and carry out the program in consultation with the Secretaries of the military departments. [18]The act required the CHCDP to have an oversight advisory committee (OAC) consisting of representatives from the comptroller general of the United States, the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, the surgeons general of the Army, the Air Force, and the Navy, and a minimum of 4 representatives from the chiropractic profession. [18]

Figure 2 Activities to start the CHCDP began at the Pentagon after the passage of the act. However, at the time of this writing, there was little evidence to support such activity. It is known that in February of 1994, Stephen C. Joseph, MD, MPH, was nominated by President William Clinton to serve as the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs. Senator Sam Nunn asked Joseph to provide written responses to questions anticipated at his confirmation hearing for the position of assistant secretary of defense for health affairs. Those questions included Joseph’s thoughts on commissioning chiropractors and the role of chiropractic in military medical services. [19] The American Chiropractic Association had representatives working to influence pending legislation pertaining to a demonstration program (letter from Richard Beacham to Rick McMichael, October 14, 1994). As well, Beacham was invited back to meet with Martin about the development of a chiropractic demonstration project within military medical clinics (letter from Robert Augsberger to Richard Beacham, September 14, 1994). Personal correspondence (letter from Robert Augsberger to Richard Beacham, September 14, 1994; letter from RF Sandweg to Richard Beacham, December 8, 1994) helps to fill this gap and provide some insight into early work on the CHCDP, as Beacham recounts (Figure 2).

Figure 3 Meetings of the OAC were not swiftly forthcoming after the passage of the act. The first meeting occurred on December 12, 1994 (letter from Susan Bailey to Richard Beacham, December 6, 1994), with a looming deadline of implementation in the next year. The OAC members representing the chiropractic profession are listed in Figure 3. [20]

Figure 4

Figure 5 After the first meeting of the Demonstration Project OAC, a series of activities ensued in haste to get the program up and running, as it was meant to be operational in fiscal year 1995, which had already commenced. By January 1995, the military surgeons general had nominated 10 MTFs as potential demonstration sites, selection criteria for chiropractors had been drafted, and the OAC had had its second meeting. The first report to Congress on the progress of the CHCDP was submitted by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs on March 2, 1995. During this time, Beacham attended all meetings of the OAC (Figure 4).

By the spring of 1995, work had begun on methods to secure chiropractors for the inaugural CHCDP positions. Each of the military branches with health care (ie, Army, Air Force, Navy) was required to hire chiropractors. However, leaders of medical services for each of these branches had little knowledge of what chiropractors did, what they required to provide their services, or what their education entailed. Thus, civilian chiropractors were procured. The Navy screened its chiropractors and contracted with them directly through the Naval Medical Logistics Command, in Fort Detrick, MD. The Army and the Air Force outsourced their hiring to a civilian contracting company, Aliron International, Inc. Job postings for chiropractors to work in the CHCDP were released around May 1995 (Figure 5). [21]

The Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs contacted the American Chiropractic Association and was informed that Jon Buriak, DC, had been active in military affairs while working at Logan College of Chiropractic. Buriak was subsequently hired by Aliron to assist in the screening and hiring of chiropractors for the Army and Air Force. He was the first person to review applications for the CHCDP and then forward those accepted to MTFs for review and possible hiring, and thus he played a key role in selecting the first chiropractors. Beacham assisted both Aliron and the Naval Medical Logistics Command in drafting the requirements for chiropractors, and then the OAC reviewed and approved the requirements.

Chiropractors On Site at Military Treatment Facilities.

Figure 6 Chiropractors were hired between July and September 1995. The hiring dates varied among MTFs. [22] Some of the chiropractors in the first group began reporting to MTFs on September 1, 1995. [23] However, the implementation manual for each base [24] was not distributed until after its approval by the OAC, which was later in September 1995 (letter from Rick McMichael to Roger Hartman, September 22, 1995). Thus, these early chiropractors and their MTF administrators initially had no manual, but they were adept at creating solutions using available resources and ingenuity. All base facilities were operational by November of 1995. [23] The first 10 MTFs were 3 Navy sites, 4 Army sites, and 3 Air Force sites, which are shown in Figure 6. [24]

The first 20 doctors of chiropractic to work in the MHS were 19 men and 1 woman. The chiropractors were from various backgrounds. Some had served in the military or were from military families. Most were from private practices, and a few of them had previously worked at chiropractic colleges as clinical faculty. The chiropractors in the CHCDP are listed in Appendix A.

The Demonstration Project was to be a 3-year program, with no guarantee that it would continue after that. Despite this fact, several of the doctors accepted positions outside of their area of residence. Rather than move their families and sell their practices, a few decided to live as “geographic bachelors.” They hired associates or brought on business partners to run their practices and had their families stay put while they moved to their designated MTFs. Some were several states away. This was a personal sacrifice that represented their dedication to the CHCDP.

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9 Despite the CHCDP being a government program and having an OAC, there was (and still is) no centralized office for chiropractic care in the MHS. Thus, the CHCDP chiropractors met as a group only twice, at meetings sponsored by Logan College of Chiropractic and Palmer College of Chiropractic (Figure 7).

Patches, logos, and slogans are part of military culture and are valued by its participants. An unknown source developed a logo for the CHCDP, which was included in the Implementation Guide. Sometimes chiropractors at MTFs would modify the logo for their specific location and include it in the local culture (Figure 8).

Chiropractors were exhilarated as they integrated into MTFs, learning the culture and customs and demonstrating what chiropractic care had to offer to the men and women of the US uniformed services. These chiropractors knew that they were honored to treat patients who were serving their country.

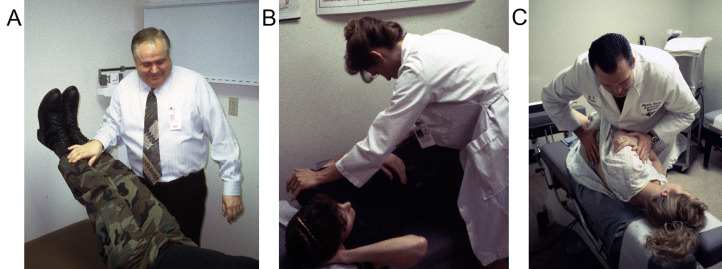

The hospital privileges (ie, procedures that providers are certified to provide health care in theMHS) that were afforded to the Demonstration Project chiropractors had been drafted by the OAC, with much input from its doctors of chiropractic. Privileges included standard chiropractic, orthopedic, and neurologic examinations (Figure 9A). Treatments included joint manipulation (Fig. 9B and 9C), soft tissue techniques, therapeutic exercise, and the use of physiotherapeutic modalities. Chiropractors had privileges to order axial skeletal radiography and standard laboratory tests, and permission to assign service members to quarters or limited light duty. [5]

Figure 10 During this time, Beacham continued in his role as senior policy consultant to the Office of Clinical Services of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs (letter from Steven Joseph to Director of Washington Headquarters Services, July 3, 1996). His primary role was to prepare the chiropractic clinics for pending accreditation visits. He provides his personal recounting of these events (Figure 10).

Chiropractic Care Well Received by Military Members.

Figure 11 As a patient, trying to see a chiropractor was not always easy. In some facilities there were up to 27 steps required before a patient could see a chiropractor. [20] Figure 11, from the Implementation Guide, shows the complicated 27-step process, with several blind loops or dead ends, required to obtain a referral for chiropractic care. [24, 31] Despite this complex referral process, some sites had, within a month of starting, a patient waiting list of 2 weeks or more for chiropractic care. [25]

The first wave of chiropractors endured constraints to initial implementation. Chiropractors at most MTFs could not practice for the first month that they were on base because they were required to wait for credentials from the hospital. At many bases, chiropractic equipment had not yet been ordered, so there were no chiropractic benches to work with. Further, not all MTFs had situated their chiropractors on base by the beginning of September of 1995. Some were installed even later in 1995.

Despite the rough start to the CHCDP, it was apparent early on that the program was becoming a success. As reported by the military leaders on the OAC, chiropractic services were well received by service members and increasingly boosted MTF productivity. One of the OAC officers stated that he believed that if the Air Force shut down the CHCDP that day, it would find a way to keep the chiropractors on board, which the Navy representative echoed. 30 This was impressive, considering the initial constraints endured by those early DCs.

The CHCDP was featured in an article in the July 1996 issue of US Medicine, a magazine that serves health care professionals working in the Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, and US Public Health Service. It was reported that 3,000 patients had been treated in the first 6 months of the CHCDP. This equated to 500 patients per month across the MTFs. John Mazzuchi, PhD, deputy assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, was quoted in the US Medicine article regarding the acceptance of chiropractic services at the MTFs: “Obviously, from the numbers that we’ve had, people are not hesitant to use those services.” [26]

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18 Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Project Site: Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton

Chiropractic services began at Camp Pendleton on October 12, 1995. [25] Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton (Figure 12) provides health care to 1 of the busiest US military installations. The largest West Coast expeditionary training facilities are located at Camp Pendleton, which covers almost 200 square miles in Southern California and bridges Orange and San Diego Counties. More than 38,000 military family members occupy base housing complexes, and there is a daytime population of 70,000 military and civilian personnel. [27]

As was the case for most of the CHCDP chiropractors, the first several weeks after joining the staff at the MTFs was exciting, new, sometimes confusing, and occasionally bewildering. Scott Gilford recounts the events he experienced with his new colleague, Jeffrey Schneider (Figure 13).

Nevertheless, equipment finally arrived. With 2 DCs, 2 chiropractic assistants, several rooms, and a large reception area, the Camp Pendleton chiropractic clinic was off to a good start (Figures 14 and 15). Gilford and Schneider were well received by leaders of the naval hospital and the Marine Corps base. Once the chiropractic clinic staff was settled in and treating patients, the command hosted a grand opening ceremony for chiropractic services (Figure 16). Over the years, Schneider and Gilford provided chiropractic care for many leaders from the hospital and high-ranking Marine Corps officers. These influential people were important allies in the advancement to include chiropractic in the MHS.

The military is generally a transient community. Whether going on or returning from deployment, moving to or from a new base, or arriving with temporary orders, there is a constant flux of patients and providers. This constant turnover presented a challenge to the chiropractors, who desired to become networked and integrated into the system. Because of the frequent changes in military health care staff, many arriving health care providers did not know that chiropractic services were available on base and many had never worked with or understood the role of a chiropractor. To keep all providers informed, much effort was continually required by Gilford and Schneider to reintroduce themselves, describe chiropractic services, and build trust.

Presence in the hospital allowed the chiropractors to frequently meet other staff members and administrators. This facilitated opportunities to strike up conversations and gain the confidence of other hospital staff. Knowing Schneider and Gilford personally made other providers more confident in referring patients for chiropractic care (Figure 17) [28] and allowed them to become comfortable seeking out chiropractic care for themselves.

Starting a new service line in a hospital, particularly a military hospital, poses challenges and requires determination. The chiropractors’ persistence and grit paid off, and some of these challenges had fulfilling outcomes. Gilford recalls his experience during implementation (Figure 18).

Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Project Extended for 2 More Years

The Demonstration Project continued for its 3-year duration. However, it became evident early on that the research component of the project was taking more time than originally planned. Thus, it was determined that more time would be needed. Within the CHCDP were embedded research studies to investigate the effectiveness of chiropractic care within the military environment. Executing these studies at 10 MTFs that were just beginning chiropractic services was difficult. There were myriad issues associated with the research projects. Thus, in 1997 it was decided to extend the CHCDP for 1 year. [29]

During 1998, 3 additional bases were added to the CHCDP (Appendix B). It was hoped that running controlled research at these 3 new facilities would be more manageable, especially because the MHS assigned a research site project manager to each of these 3 MTFs. The work that the chiropractors and research consultants performed at these MTFs was important in producing outcomes that could be evaluated by the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs to determine if the CHCDP had demonstrated whether integrating chiropractic services into MHS was feasible and advisable.

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21 Chiropractors would often move from 1 MTF to another. For example, Terence Kearney briefly moved from Travis Air Force Base to Walter Reed Army Medical Center, and then settled into the National Naval Medical Center, where he still works at this time. Jon Buriak moved from his role of consultant to Aliron and began chiropractic services at Walter Reed Army Medical Center (Figure 20). Charles Stulga moved from Ft Benning to assist in opening the new services at Lackland Air Force Base with Matthew Williams, who was new to the CHCDP. William “Bill” Morgan (Figure 19) and Williams joined the ranks of the CHCDP to complete the complement of chiropractors at the new MTFs.

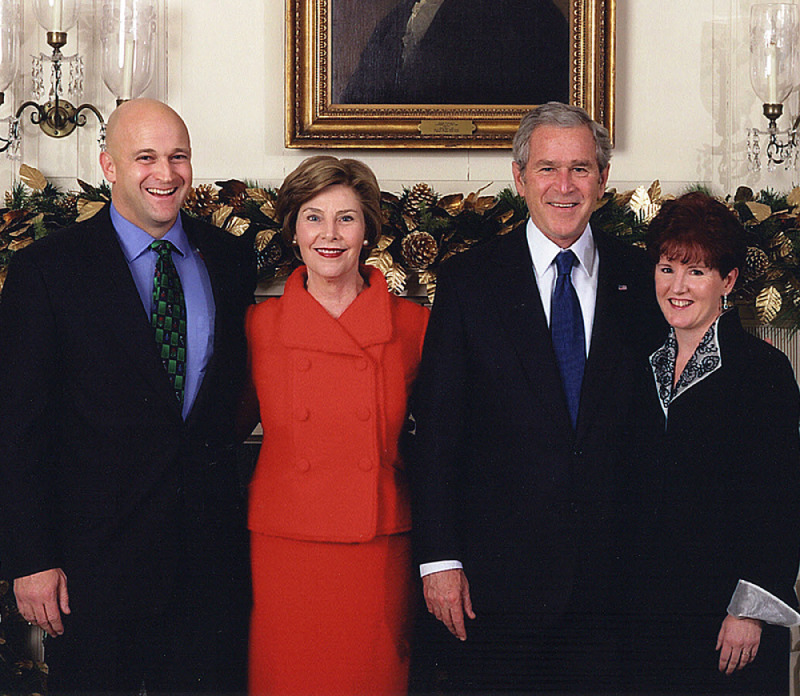

The following year, the CHCDP was given another extension, through the end of September 1999, in the hopes of completing the research. [29] Although the research was an important aspect of the CHCDP at the 3 new MTFs, the main mission at these facilities was to provide care to patients. Also, these MTFs were high-visibility facilities where legislators, Cabinet members, and high-ranking military officers often visited. The chiropractors at each of these MTFs were instrumental in providing a positive image of the profession to military leaders, dignitaries, and the public (Figure 21).

The CHCDP was finally considered complete in September 1999. However, it was unknown whether chiropractic care would continue to be offered in the MHS at that time. The chiropractors were mentally prepared to leave their jobs, because the CHCDP was not supposed to be a permanent program. Fortunately, the Department of Defense leadership decided to continue to fund the chiropractic positions until a decision was made whether to keep chiropractic care as a permanent benefit for service members.

The military had hired a consulting firm (Birch & Davis Associates, Inc, Falls Church, VA) to provide administrative services and other functions to the government during the CHCDP. After the CHCDP was complete, Birch & Davis submitted a final report, commonly known as the Birch & Davis report, to the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs in February 2000. [30] The chiropractic members of the OAC were provided the opportunity to review the Birch & Davis report and submit a response. They did so, submitting their report at the same time. The OAC chiropractors were assisted in preparing the report by Muse and Associates (Washington, DC); thus, their report is often referred to as the Muse report. [31]

Although there were points of disagreement between the reports, both highlighted many positive aspects of the CHCDP. The Birch & Davis report corroborated the early observations of the deputy assistant secretary of defense for health affairs pertaining to utilization of chiropractic care. In final data analyses, it was shown that “active duty beneficiaries clearly have a strong demand for chiropractic services, and this demand is strictly increasing with age.” [30] Doctors of chiropractic attained higher levels of patient satisfaction than other providers. Chiropractic care in the CHCDP also demonstrated higher levels of effectiveness for low back pain when compared to traditional medical care. The Birch & Davis report stated, “The health status analysis shows that patients seen by doctors of chiropractic showed greater improvements in five health status scales (Roland-Morris, pain severity, performance level, activity level, and perceived health).” pIV-48 Chiropractic care was also associated with higher levels of military readiness for duty when compared to traditional medical treatment. The chiropractors had made the profession proud.

After the Demonstration Project: Establishment of Permanent Benefit Program

After the CHCDP, Congress in the year 2000 approved the development of permanent chiropractic services and benefits for members of the uniformed services. [32] This ushered in the expansion of the chiropractic care benefit to several MTFs,22 starting as soon as September 2002 (Appendix C).

With this new influx of DCs, more communication between the MHS chiropractors commenced. As well, lessons learned from starting chiropractic clinics in the CHCDP were shared with chiropractors starting clinics in the new military locations. Despite being aware of some of the struggles and victories of the CHCDP chiropractors, the “second wave” DCs still had to learn for themselves what it was like to be a chiropractor in the MHS.

New Permanent-Benefit Site: Naval Medical Center San Diego

Naval Medical Center San Diego was one of the first MTFs to start chiropractic services after the passage of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2001. It is the largest West Coast military tertiary care center, with more than 6,500 staff members who serve more than 100 000 beneficiaries. A 272-bed multispecialty hospital, the main complex consists of 1.2 million square feet on a 78-acre campus.33 An additional 11 community outpatient care clinics are part of the command. [34]

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Figure 25

Figure 26

Figure 27 Three chiropractors were contracted to start at Naval Medical Center San Diego on September 29, 2003: Galen Kishinami, David Ward, and Bart Green. Ward was 1 of the original CHCDP chiropractors, transferring from Scott Air Force Base to San Diego. Kishinami transferred from Andrews Air Force Base, and Green was new to the MHS. Kishinami and Green were part of the second wave of DCs in the MHS. Regardless of their level of experience in the MHS, each was uncertain about how chiropractic would be received at a flagship naval medical center. Green recounts his early experiences (Figure 22).

One of the unique traits of the MHS chiropractors has been their capacity to adapt to their situations. Chiropractors have been placed in departments of sports medicine, orthopedics, physical therapy, and others, and had superiors in nearly every health care profession. Although this could have been a barrier to chiropractic services among MTFs, it has instead provided improved integration and served as a facilitator to building chiropractic services. At Naval Medical Center San Diego, chiropractors worked in entirely integrated clinics; there were no stand-alone chiropractic offices (Figure 23).

Space, personnel, and resources were shared by many disciplines, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, primary care, sports medicine, orthopedics, and other disciplines. In San Diego, all 3 chiropractors had 1-month patient waiting lists before they even arrived, and referrals were received from many departments. For the program to be a success, integration was a critical part of the provision of chiropractic care in the MHS. Green recounts his experiences with integration (Figure 24).

Referrals were from various departments, including between chiropractic departments, especially when MTFs with chiropractors were located in close proximity. With less than 50 miles separating the Camp Pendleton and San Diego chiropractors, patients were sometimes referred between chiropractors at the 2 commands. Communication between the locations facilitated the integration of services in the San Diego area (Figure 25).

Chiropractic care was welcome relief, not only to the patients who were served but to their commanders, who relied upon their troops to be fit for duty (Figure 26). It is challenging for pilots with musculoskeletal problems to fly aircraft, and there are very few medications that pilots are allowed to take while on flight orders. [35, 36] The same is true for special operators of the Sea, Air, and Land (SEAL) teams, police officers, submariners, aircraft maintainers, explosive ordnance personnel, and other special groups the chiropractors served. With integration and requests from leaders of various special populations, chiropractic care in San Diego expanded from 3 clinics to 6 within a few years, including the prestigious Comprehensive Combat and Complex Casualty Care at the naval medical center. [8, 37]

By the time the permanent benefit program started, published studies about chiropractic care in the MHS were sorely needed. There were no studies about chiropractic care of military members authored by a chiropractor working in a MTF. Chiropractors were hired to provide care, not to do research. It was expected that 36 of the 40 weekly work hours were spent on direct patient care, providing no time for academic or research pursuits. It was not until 2005, the 10th year of chiropractic in the MHS, that an article was submitted to a peer-reviewed journal by an MTF chiropractor, resulting in the first such publication the next year. [36] The article, a case report authored by an interdisciplinary team at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, broke the ice; more articles were published in later years. [8, 10, 35-39] Many chiropractors found the opportunity to be fully immersive at their locations. Participation in community events, rites of passage, and other activities was welcome and enriched the experience for both chiropractors and the community. Green describes his experience (Figure 27).

The permanent benefit was attractive to many chiropractors, but there was 1 doctor who was particularly eager to participate. Beacham worked at 3 MTFs after his time as senior policy consultant in the CHCDP: Kimbrough Ambulatory Care Center at Ft Meade, Malcolm Grow Medical Center at Andrews Air Force Base, and David Grant Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base.

New Permanent-Benefit Sites: Kimbrough Ambulatory Care Center,

Malcolm Grow Medical Center, and David Grant Medical Center

Kimbrough Ambulatory Care Center was originally an Army hospital that today is much larger and part of the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. It offers a full range of health care services, including an emergency facility and surgery center. [40] Malcolm Grow Medical Center provides medical homes for all ages and a complete range of medical services, subspecialties, surgery, dental care, aerospace medicine, and ancillary service lines. It provides medical care for over 500 000 beneficiaries. [41] David Grant Medical Center also provides a full spectrum of health care to more than 130,000 TRICARE eligible patients in the San Francisco/Sacramento area, in addition to more than 377,000 eligible veterans. [42]

Figure 28 Beacham’s perspective as a treating doctor in the expansion period was unlike those of the other chiropractors, because he had served as the senior policy consultant to the OAC during the entire CHCDP and had taken part in the program before it even started. He recounts his experience (Figure 28).

As can be seen through these examples and recountings of events, providing chiropractic care in the MHS was hard but rewarding work. Fulfillment often comes in ways that are beyond financial, such as being part of a team that is responsible for achieving excellence in care or delivers effectiveness in ensuring military readiness. Sometimes simply helping a service member pass their physical fitness test was the greatest reward of all. Donald Baldwin at Naval Hospital Jacksonville, himself a Navy veteran, related:I’m proud of my wall of 50+ baseball caps from every ship and squadron in our area, given by patients or COs as a small gesture of appreciation. In private practice, patients are appreciative to a degree. However, they come in and pay for a service, expect results and leave. In the military, no money changes hands, but the appreciation to finally have someone that can find their problem, fix it and yes, save a career, to them is a gift from heaven. We go home each night feeling GOOD about what we are doing. [43]

DISCUSSION

Although it is impossible to predict the future of MHS chiropractic services, we hope to see continued growth in several areas. The Department of Defense states that it has established a chiropractic benefit for active duty personnel. [22] It has claimed in official policy that “the chiropractic health care benefits program is fully implemented.” [44] However, chiropractic care is available at only 60 of approximately 400 (15%) existing MTFs. This shows that the program is not yet fully implemented at all facilities. Given our knowledge of the system, it may be reasonable to say that the majority of MTFs globally include rehabilitation teams. As this report and other research suggest, chiropractors can be valuable assets in these health care teams.

Integration of chiropractic services has not yet been implemented at 85% of facilities. We believe that chiropractors should be included at all MTFs where there are rehabilitation teams. Given that approximately a dozen acts of Congress were required to get the chiropractic program this far, [8] it stands to reason that further lobbying and legislation might be required to make this a reality. We suggest that chiropractic political organizations should lobby to make this happen.

Although active duty service members have access to chiropractic care on base, this is not necessarily true for their dependents or for some retirees. During the early years of the Demonstration Project, chiropractors were allowed to provide care for dependents and retirees. This was a successful part and much sought-after benefit of the program.

However, when the Department of Defense permanently adapted the program, it no longer provided these individuals with chiropractic care. Thus, dependents are not allowed to see the chiropractors at the military facilities and must pay out of pocket for care outside of MTFs. Military retirees may seek chiropractic care if it is available at their closest Veterans Affairs facility. If not, they may be able to acquire a referral to a chiropractor in the community. However, they are ineligible for care to see an MTF chiropractor, even if this care is available at an MTF close to their home. Thus, they too must pay out of pocket for chiropractic care unless they are approved for care on a fee basis in the community. To us, this seems unjust. Even if chiropractic were utilized similarly to a dental benefit, with a copayment for non?active duty members, we believe that it would be an important addition to MHS health care. Although there has been discussion of such a concept, we are unaware that it has progressed to action. [45]

Health care disciplines in the MHS have a point person (sometimes known as a specialty advisor) across facilities who is a peer. This person acts as a representative of the profession and assists in coordinating professional activities within the MHS. Currently, there is no such position in the MHS for the chiropractic profession. There is therefore no central chiropractic director or coordinator to provide administrative oversight of programmatic development, national coordination of communication between MHS chiropractors, and efforts toward standardizing care, conducting research, enhancing continuing education, and developing training opportunities. After 25 years of the success of this program, we believe that it would be timely for MHS to facilitate and encourage its chiropractors to communicate, identify areas of needed improvement, and standardize the delivery of chiropractic care being provided.

In 1992, Congress passed the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993, which allowed the US military the ability to appoint chiropractors as commissioned officers. [13] Nearly 30 years later, none have been appointed. Budget shortfalls have been the prevailing explanation for a lack of action on this item. We hope to see this change in the future. Commissioning chiropractors in the military is another item that will likely take further legislative action.

We believe that further development of the chiropractic program will be realized with more research. With an increased concern over the use of medications (eg, opioids) for pain management, chiropractic can be assessed for its merit as a desirable form of nonpharmaceutical treatment for musculoskeletal concerns. Given the many military occupations that prohibit individuals from taking prescription medications, we have seen that many service members prefer chiropractic over medications. Similar sentiments have been shown by the physicians who watch over their troops. Recently, studies have shown benefits of chiropractic care to military service members.46-49 We hope that this is just the beginning and that with more evidence, the chiropractic profession will continue to evolve in the MHS.

We write this article in honor of the silver anniversary of chiropractic in the MHS and the chiropractors who made it a success by honoring the positions that they occupied. Although health care is its own calling, there is something extraordinarily meaningful about watching over the health of the men and women who protect our nation. The late Greg Lillie summed this sentiment up nicely: “What a privilege it is to be able to provide chiropractic care to our active duty military personnel. It is truly an honor to work with the men and women serving our country. I thank God daily for having such an opportunity.” [50]

Limitations

As this is the first article to chronicle the history of chiropractic in the MHS, we encountered some difficulties in filling in some gaps. This article is limited to the early years of the program, leaving the remaining expansion of the permanent-benefit program untold. It does not recount every event during the 25 years of chiropractic in the MHS, particularly some of the significant struggles arising out of the real or perceived discrimination against chiropractors and turf wars. The passing of some of the original CHCDP chiropractors has left gaps in the history of chiropractic in the MHS. This affected our research, as evidenced by our inability to find names for some of the original doctors in Figure 7. We were unable to contact some of the CHCDP chiropractors, as their contact information led us to dead ends or there was no contact information. Their recollections or personal collections of materials may have provided further context and substance for this research. The contents of this article are also subject to our own recall biases. It is based on our experiences and does not necessarily represent the experiences had by chiropractors at other MTFs.

CONCLUSION

Whether starting in the Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Project (CHCDP) or the permanent benefit program, the early Military Health System (MHS) chiropractors were instrumental in demonstrating that chiropractic care was beneficial to service members, effective, and feasible to implement. Many chiropractors sacrificed their family lives and served as geographic bachelors to initiate the program. Building relationships with other providers, staff, administrators, and military leaders was essential to the success of these programs. For chiropractors, this was a formidable task, because hospital-based chiropractic care was not common during the period that we report.

There were many noteworthy achievements made in the early years of chiropractic implementation in the MHS. These pioneering chiropractors are commended for their outstanding representation of the profession while caring for the deserving members of the United States uniformed services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the many people who helped us confirm facts, provided pictures, reviewed the manuscript, and located colleagues, particularly Perry Paschall, Michael Clay, Duane Lowe, Jeffrey Schneider, Bill Morgan, Colette Peabody, Patrick Casey, Terence Kearney, David Ward, Galen Kishinami, and Arlan Fuhr.

FUNDING SOURCES AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors received no funding for this study. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any agency, educational institution, or association (eg, National University of Health Sciences, Stanford

References:

Stochkendahl MJ, Rezai M, Torres P, et al.

The chiropractic workforce: a global review.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2019;27:36.Himelfarb I, Hyland JK, Ouzts NE, et al.

Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2020

Greeley, CO: National Board of Chiropractic Examiners; 2020.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, et al.

A Scoping Review of Biopsychosocial Risk Factors and Co-morbidities for Common Spinal Disorders

PLoS One. 2018 (Jun 1); 13 (6) :e0197987Devitt M.

Spotlight on William Morgan, DC

Dynamic Chiropractic – March 11, 2004, Vol. 22, Issue 06Department of the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

BUMED Instruction 6320.66D.

Washington, DC: The Bureau; 2003.Department of the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

BUMED Instruction 6320.66E.

Washington, DC: The Bureau; 2006.Chiropractic Health Care Program.

TRICARE management activity. Available at:

https://tricare.mil/Plans/SpecialPrograms/ChiroCare

Accessed September 2, 2020.Dunn AS, Green BN, Gilford S.

An Analysis of the Integration of Chiropractic Services Within

the United States Military and Veterans' Health Care Systems

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 749–757Rousmaniere K.

Historical research.

In: deMarrais K, Lapan SD, eds.

Foundations for Research: Methods of Inquiry in Education and the Social Sciences.

Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004:31-50.Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ, Tucker J.

Chiropractic Practice in Military and Veterans Health Care:

The State of the Literature

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2009 (Aug); 53 (3): 194–204Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ.

Integration of Chiropractic Services in Military and Veteran Health Care Facilities:

A Systematic Review of the Literature

J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016 (Apr); 21 (2): 115–130Department of Defense Authorization Act of 1985,

98 Stat 2492, x632(b).National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993,

Public Law 102-484.Statement of the American Hospital Association with respect to the profession of chiropractic and hospitals.

Hospitals. 1987;61:80.Getzendanner S.

Permanent injunction order against AMA.

JAMA. 1988;259(1):81-82.Fuhr A.

Activator Methods Chiropractic Technique.

St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1996.Chiropractic positions available at 7 US Army and Air Force bases.

ACA Today. 1995:(6):2.National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1995,

Public Law 103-337, x731.Joseph SC.

Pre-Hearing Questions to Dr Joseph Submitted by Senator Nunn. 1994.

Located at: Green Archives, Escondido, California.Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs.

Second Report to Congress on the Status of the Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Program (CHCDP).

Washington, DC: Department of Defense; 1995.DOD advertises for demonstration program.

ACA Today. 1995:(5):2.Government Accountability Office.

DOD’s Chiropractic Health Care Program

Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office; 2005.

GAO-05-890R.Beacham RF.

Notes of Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Program Oversight and Advisory Council meeting.

Washington, DC; November 21, 1995. Located at:

Green Archives, Escondido, California.Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs.

Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Program Site Implementation Guide.

Washington, DC: Department of Defense; 1995.Kovic J.

Chiropractic Care at Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton.

Navy Medical Newsletter. December 9,1995:1 .Late M.

DoD chiropractic study popular with patients.

US Med. 1996:(7):24.Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton: the West Coast’s premier fleet marine force training base.

Available at: https://www.pendleton.marines.mil/About/Introduction.aspx

Accessed September 9, 2020.Pioneering doctors: demonstration participants clear the path for chiropractic in the military.

J Am Chiropr Assoc. 2001;38 (2):20-25.National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1998.

Public Law 105-85, x739.Birch & Davis Associates Inc.

Final Report: Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Program.

Falls Church, VA: Birch & Davis; 2000.Goodman G, Beacham R, Evans D, Ferguson P, McMichael R, Phillips RB.

Report on the Department of Defense Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Program.

Washington, DC: Muse and Associates; 2000.National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2001.

Public Law 106-398.About us.

Naval Medical Center San Diego. Available at:

https://www.med.navy.mil/sites/nmcsd/pages/command/ command-about-us.aspx

Accessed September 25, 2020.Naval Branch Health Clinics.

Naval Medical Center San Diego. Available at:

https://www.med.navy.mil/sites/nmcsd/ Pages/Patients/branch-and-dental-clinics.aspx

Accessed September 25, 2020.B.N. Green, A.S. Dunn, S.M. Pearce, et al.,

Conservative Management of Uncomplicated

Mechanical Neck Pain in a Military Aviator

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2010 (Jun); 54 (2): 92–99Green BN, Sims J, Allen R.

Use of Conventional and Alternative Treatment Strategies

for a Case of Low Back Pain in a F/A-18 Aviator

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2006 (Jul 4); 14: 11Goldberg C.K., Green B., Moore J.

Integrated Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation Care at a Comprehensive

Combat and Complex Casualty Care Program

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 781–791Green BN, Schultz G, Stanley M.

Persistent synchondrosis of a primary sacral ossification center in an adult with low back pain.

Spine J. 2008;8:1037-1041.Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ.

Chiropractic in U.S. Military and Veterans’ Health Care

Military Medicine 2009 (Jun); 174 (6): vi–viiKimbrough Ambulatory Care Center.

TRICARE management activity. Available at:

https://kimbrough.tricare.mil/ About-Us/Our-History

Accessed September 27, 2020.TRICARE Management Activity.

Malcolm Grow Medical Clinics and Surgery Center.

Joint Base Andrews, MD:

TRICARE Management Activity; 2013.David Grant USAF Medical Center/ Available at:

https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/Patient-Portal-for-MHS-Quality-

Patient-Safety-and-Access-Information/See-How-Were-Doing/Air-Force/AFMC-60TH-MED-GRP-TRAVIS?DmisId=0014

Accessed September 27, 2020.Baldwin D.

Spotlight.

Carpe Spinalis. 2004;1(5):1-3.Casscells SW.

Health Affairs Policy 07-028: Revision of Chiropractic Care for Active Duty Service Members

of the Uniformed Services Health Policy: 03-021

Washington, DC: Department of Defense; 2007.Bushatz A.

Tricare moves toward chiropractic coverage. Available at:

https://www.military.com/daily-news/2019/09/ 26/tricare-moves-toward-chiropractic-coverage.html

Accessed September 27, 2020.Goertz CM, Long CR, Hondras MA, Petri R, Delgado R, Lawrence DJ, et al.

Adding Chiropractic Manipulative Therapy to Standard Medical Care

for Patients with Acute Low Back Pain: Results of a Pragmatic

Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 (Apr 15); 38 (8): 627–634Goertz CM, Long CR, Vining RD, Pohlman KA, Walter J, Coulter I.

Effect of Usual Medical Care Plus Chiropractic Care vs Usual Medical Care

Alone on Pain and Disability Among US Service Members With

Low Back Pain. A Comparative Effectiveness Clinical Trial

JAMA Network Open. 2018 (May 18); 1 (1): e180105 NCT01692275Vining R, Long CR, Amy Minkalis M, Gudavalli R, Xia T, Walter J

Effects of Chiropractic Care on Strength, Balance, and Endurance in

Active-Duty U.S. Military Personnel with Low Back Pain:

A Randomized Controlled Trial

J Altern Complement Med 2020 (Jul); 26 (7): 592–601–693DeVocht J.W., Vining R., Smith D.L., Long C., Jones T., Goertz C.

Effect of Chiropractic Manipulative Therapy on Reaction Time

in Special Operations Forces Military Personnel:

A Randomized Controlled Trial NCT02168153

Trials. 2019 (Jan 3); 20 (1): 5Lillie G.

Association.

Carpe Spinalis. 2003;1(4):3.

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 1-25-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |