Hospital-Based Chiropractic Integration Within a

Large Private Hospital System in Minnesota:

A 10-Year ExampleThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 740–748 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Richard A. Branson, DC

Director of Chiropractic Services,

Fairview Sports and Orthopedic Care,

Fairview Health System,

Burnsville, MN 55337, USA.

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this article is to describe a model of chiropractic integration developed over a 10-year period within a private hospital system in Minnesota.

METHODS: Needs were assessed by surveying attitudes and behaviors related to chiropractic and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) of physicians associated with the hospital. Analyzing referral and utilization patterns assessed chiropractic integration into the hospital system.

RESULTS: One hundred five surveys were returned after 2 mailings for a response rate of 74%. Seventy-four percent of respondents supported integration of CAM into the hospital system, although 45% supported the primary care physician as the gatekeeper for CAM use. From 2006 to 2008, there were 8294 unique new patients in the chiropractic program. Primary care providers (medical doctors and physician assistants) were the most common referral source, followed by self-referred patients, sports medicine physicians, and orthopedic physicians. Overall examination of the program identified that facilitators of chiropractic integration were (1) growth in interest in CAM, (2) establishing relationships with key administrators and providers, (3) use of evidence-based practice, (4) adequate physical space, and (5) creation of an integrated spine care program. Barriers were (1) lack of understanding of chiropractic professional identity by certain providers and (2) certain financial aspects of third-party payment for chiropractic.

CONCLUSION: This article describes the process of integrating chiropractic into one of the largest private hospital systems in Minnesota from a business and professional perspective and the results achieved once chiropractic was integrated into the system. This study identified key factors that facilitated integration of services and demonstrates that chiropractic care can be successfully integrated within a hospital system.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction

The purpose of health care is to improve the health of the public we serve. [1] Many types of providers, treatments, and tests exist in our health care system to meet this simple yet profound purpose. The complexity of the human body with all of its potential states of pain, dysfunction, and disease can overwhelm any individual health care provider. Good health care does not function as an individual or professional silo. Collaboration between health care providers and disciplines is essential in providing safe, quality, health care. [2] Within the medical profession alone, there is a dizzying array of subspecialties to treat all that ails us. Add to this list the choice of allied health professions such as dentistry, nursing, physical therapy, psychology, dietetics, and a vast array of medical technicians; and the choices for diagnosis and treatment become even more confusing. The health care industry is a complex web of medical, allied, and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) providers. Some have referred to this confusing array of choices as being akin to shopping in the supermarket of health care. [3] The public and traditional medical providers that treat them must also contend with the various regulated and unregulated CAM professions. Near the top of this CAM list is the profession of chiropractic. Started over a century ago, this profession has metamorphosed into a regulated profession that lives somewhere between the traditional and alternative world of health care. [4] The vast majority of those in the chiropractic profession still practice in single-provider clinics. [5]

Collaboration between the traditional medical and chiropractic professions is a relatively new phenomenon. Historically, the 2 professions have worked in isolation of one another and often to extremes. In fact, as recent as 1983, the American Medical Association held that it was unethical for medical doctors to associate with the chiropractic profession, as it was labeled an unscientific cult. [6]

In 1993, Eisenberg et al [7] published a pivotal article in the New England Journal of Medicine on the use of unconventional medicine in the United States. This article reported a higher use of unconventional treatment, such as chiropractic, than previously published and sparked an interest in hospital-based care systems around the country to begin exploration of such treatments within traditional care systems. [8] Since that time, private hospitals around the country have begun to open their doors to the inclusion of CAM treatments. This has lead to a small but growing number of chiropractors being used by private hospital systems. The integration of chiropractic into mainstream health care is a model reviewed and ultimately recommended in 2005 by the Institute for Alternative Futures. [9]

The purpose of this article is to describe(1) the process of integrating chiropractic into one of the largest private hospital systems in Minnesota from a business and professional perspective

(2) the facilitators and barriers to integration, and

(3) the results achieved once chiropractic was integrated into the system.

Methods

Setting for the Integrative Model

Fairview Health Services is one of the largest private hospital systems in the state of Minnesota. This hospital is a not-for-profit health care system and was founded in 1906. In 1997, the hospital merged with the University of Minnesota, forging an academic- and community-based health care system. The system currently has more than 19,000 employees, 7 hospitals, 37 primary care clinics, and 50 specialty clinics throughout the state. [10]

In the early 1990s, a branch of the hospital's rehabilitation division began to explore the idea of incorporating chiropractic services within the walls of the hospital system. Discussions between one of the regional directors of the outpatient rehabilitation division and a solo chiropractor began. The concept of leasing space within one of the outpatient rehabilitation clinics to a solo chiropractor was presented to the rehabilitation's board. The idea was looked upon favorably, but concern about medical physician referrals to the outpatient rehabilitation clinics system with a doctor of chiropractic was considered too large of a barrier. This study was reviewed and approved for ethical consideration by the System Director, Fairview Orthopedic Services.

Needs Assessment: CAM Survey

In 1998, Fairview again explored the idea of adding chiropractic services within the hospital system. The director of outpatient rehabilitation services was pursuing a Master's in Health Care Administration degree and surveyed a portion of local family practice doctors on CAM integration into a hospital-based care system for his Master's thesis. The survey can be seen in Appendix A. The family physicians surveyed in this study practiced in the greater Minneapolis–St Paul (Twin Cities) metropolitan area. Minneapolis–St Paul is located in east central Minnesota. At the time of the survey, the population was approximately 2.5 million. The local primary care physicians were accustomed to functioning in a gatekeeper role due to the high proportion of managed care arrangements in this market. The physicians surveyed were members of Fairview Physician Associates (FPA), a physician-hospital organization affiliated with Fairview Health System. At the time of the survey, FPA was composed of 727 primary care and specialty physicians who provided care at more than 150 clinics and hospital settings located throughout the metro area. There were 314 primary care physicians of which 142 are family practice. A 2-page, 14-question self-reported survey was administered in early 1998 to these 142 FPA family practice medical providers regarding their interest and perceived value of several forms of CAM treatments. A copy of this survey can be obtained by written request from the author.

Data Collection: Chiropractic Service Line Referral Patterns

As of July 2005, the hospital system had converted most departments to an electronic medical record system, including the chiropractic service line. A full 3-year data set of referral patterns for the chiropractic program was extracted from the electronic medical record system for calendar years 2006 to 2008.

All chiropractic patient and financial data are stored in a database that is extracted from Epic (Epic Systems Corp, Verona, WI), the hospital's electronic medical record system. Crystal Reports software version XIR2 (Newtown Square, PA) was used to write a report and pull data related to all patient referrals for each of the 3 calendar years. The extracted data were run in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) format and grouped by the name of the referring provider, total number of referrals by provider, and provider address with the exception of self-referred patients. Only the total number of self-referrals by year was extracted for each year. No corresponding name or address was included in the data pull for this group. The data set was then sorted by address and frequency of referral to determine the distribution of patient referrals.

Four additional statistical measures (sex, mean age, patient visit average, and primary diagnosis) were obtained from the hospitals electronic medical record system for calendar year 2008. Because of the large number of patient records, only a single year of descriptive data was extracted. The method used to extract this data from the electronic medical record system was performed in the same manner described regarding the chiropractic referrals. Once the data set was available in a Microsoft Excel format, data were deidentified for patient confidentiality. Mean, ranges, and SDs were obtained for sex, mean age, and patient visits. Primary diagnoses were sorted by frequency of utilization.

Results

Data Collection: the CAM Survey

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

Figure 1

Table 6 One hundred five surveys were returned after 2 mailings for a response rate of 74%. The mean age of the respondents was 45.1 years. Seventy-four percent of the respondents were male. Although a high percentage of respondents (74%) supported integration of CAM into the hospital system, 45% of the respondents still wanted the primary care physician as the gatekeeper for CAM use. The descriptive data regarding personal/family use of CAM therapies by the respondents are in Table 1.

The survey also addressed 5 aspects regarding the level of CAM knowledge by the surveyed physicians. Table 2 summarizes respondent knowledge of CAM. Most family physicians surveyed agreed that they should have some level of knowledge and be able to advise their patients regarding the use of CAM therapies.

Physicians were also asked about personal incorporation of CAM therapies in their own practice as well as existing referral relationships with CAM providers. Table 3 and Table 4 provide a summary of these survey findings. The survey found that half of all physicians had existing referral relationships with chiropractors. This finding supported the development of a chiropractic service line within the hospital system.

Data Collection: Chiropractic Patient Referrals

During the 2006 to 2008 calendar years, 8,294 unique new patients entered the chiropractic program. Table 5 presents a summary of referral totals by each calendar year. A moderate reduction in the total number of unique new patients was observed for calendar year 2008. The chiropractic program had a full-time provider resign at the end of the third quarter of 2008. This workforce reduction is the most likely rationale for the noted reduction in total new patient volume for 2008.

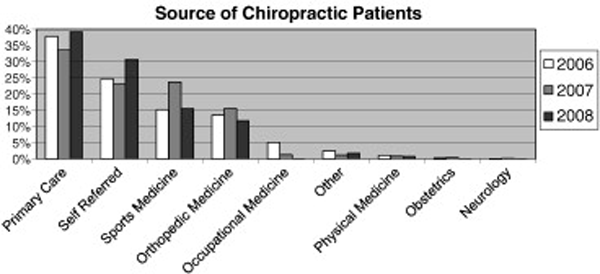

Primary care providers (medical doctors and physician assistants) were the most common referral source for all 3 years, followed by self-referred patients, sports medicine physicians, and orthopedic physicians. Figure 1 shows a summary of the service line's 3-year referral source trends. In 2007, there was a notable increase in the number of sports medicine referrals. In 2007, a full-time doctor of chiropractic was relocated to an outpatient clinic with several sports medicine and orthopedic surgeons in the same clinic. This chiropractor was able to quickly develop a referral relationship with physicians on staff at this facility.

Data Collection: Chiropractic Service Line Descriptive Statistics

Of the 2,325 patients seen in 2008, 69.4% were female. The mean age was 42 years (range, 4-93; SD, 14.86). Patients were treated an average of 4 visits (range, 1-21; SD, 3.41). Table 6 provides a summary of the top 10 primary diagnosis codes. The top diagnostic code used by the chiropractors was thoracic segmental joint dysfunction (12.7%). When the codes are sorted by spinal region, the most commonly treated region is the lumbar spine (28.8%) followed by the cervical region (24%) and the thoracic region (16.5%). In total, 69.3% of the top 10 primary diagnosis codes were spine related. This finding is consistent with published data that chiropractors commonly treat spine-based conditions. [11]

Discussion

Business Development Plan

The findings from this CAM survey suggested that most medical providers who referred patients to the outpatient rehabilitation program were open to the inclusion of CAM treatments within the rehabilitation division of the hospital. This finding sparked the investigation of CAM use within the hospital system. The hospital identified 17 different forms of treatment, which were deemed unconventional therapy, in use by current employees of the hospital system. Figure 2 provides a list of these 17 therapies.

Figure 2. 17 Unconventional therapies in use at the hospital

Acupressure

Acupuncture

Biofeedback

Counseling

Dietary lifestyle changes

Healing touch

Herbal medicine

Homeopathy

Massage therapy

Manual therapy – Mobilization and Manipulation

Meditation

Music therapy

Psychotherapy

Relaxation techniques

Support groups

Tai Chi

Yoga

After review of these findings, it was decided by the director of the outpatient rehabilitation division to present the concept of hiring a chiropractor to the rehabilitation board. After much debate by the board and several internal hospital committees, the hospital system hired its first doctor of chiropractic. This new hire was added to an outpatient physical therapy department in a clinic with 5 physical therapists and a single athletic trainer. Chiropractic job description and scope of practice were created within the hospital system with input from the newly hired doctor of chiropractic and hospital staff. The scope of practice mirrored the state's scope of practice. Although a wide range of disorders was evaluated and treated by chiropractors within the hospital, there was an emphasis on evidence-based musculoskeletal and spine-based diagnosis and treatment.

Applications to participate as an in-network provider were sent to all major insurance companies and chiropractic managed care organizations operating within the Twin Cities market. Additional setup time regarding appropriate clinical documentation, billing, referral pads, and equipment delayed actual patient care for approximately 60 days. A marketing campaign was initiated by the hospital system to educate the local community and caregivers regarding a new chiropractic service line.

Table 7 Within 6 months, the care system hired a second chiropractor because of increasing demand, patient volumes, and interest in expanding chiropractic services to a different geographic region of the Twin Cities. Over the next several years, the program has expanded and has been contracted to offer chiropractic services at 8 different locations around the Twin Cities. These services have been provided by 6 different chiropractors over the 10 years of the program's existence. The program has seen growth and recession of locations and numbers of chiropractors. The hospital's chiropractic time line is in Table 7.

Facilitators of Chiropractic Integration

There are several facilitators that were identified regarding the inclusion, acceptance, and growth of the chiropractic service line in this private hospital system. The first was a growth in the literature and interest in CAM therapies. This increase in identification of CAM use by the public created awareness of and interest in unconventional forms of care by hospital systems.

The second facilitator was relationship building. The author remained in contact with the director of the rehabilitation program starting in the early 1990s. This key person was interested in CAM therapy use and explored the openness of referring physicians to inclusion of CAM therapy within the walls of the hospital system. This administrative leader in the medical system had the intellectual, academic, collegial, and networking ability to blend the biomedical and CAM worlds successfully. This key person was actively engaged in the pursuit of chiropractic integration within the hospital and centered his Master's thesis around data collection of this idea. Without this engaged hospital administrator, the concept of chiropractic inclusion would never have become a reality.

The third facilitator relates to scientific evidence. The first chiropractor hired resigned from a chiropractic research department to join the hospital system. A firm knowledge of the scientific basis of safety and effectiveness of treatment within the scope of chiropractic care was essential. This knowledge base was critical during initial discussions at the numerous hospital committee meetings and physician presentations. This firm resolution by the chiropractor, hospital administration, and clinical staff to use evidence-based evaluation and treatment methods was a key component to the acceptance and growth of the chiropractic service line within the hospital system.

Figure 3 A fourth facilitator relates to physical space. The first clinic to offer chiropractic services was being remodeled at the time this additional service was being explored. This timing allowed the administrators in the hospital to design a clinic with additional space specifically for chiropractic services. Many clinics within a large hospital system may not have the physical space within related departments to add additional caregivers or a new service line. Space provision in the clinic redesign was critical to the addition of chiropractic.

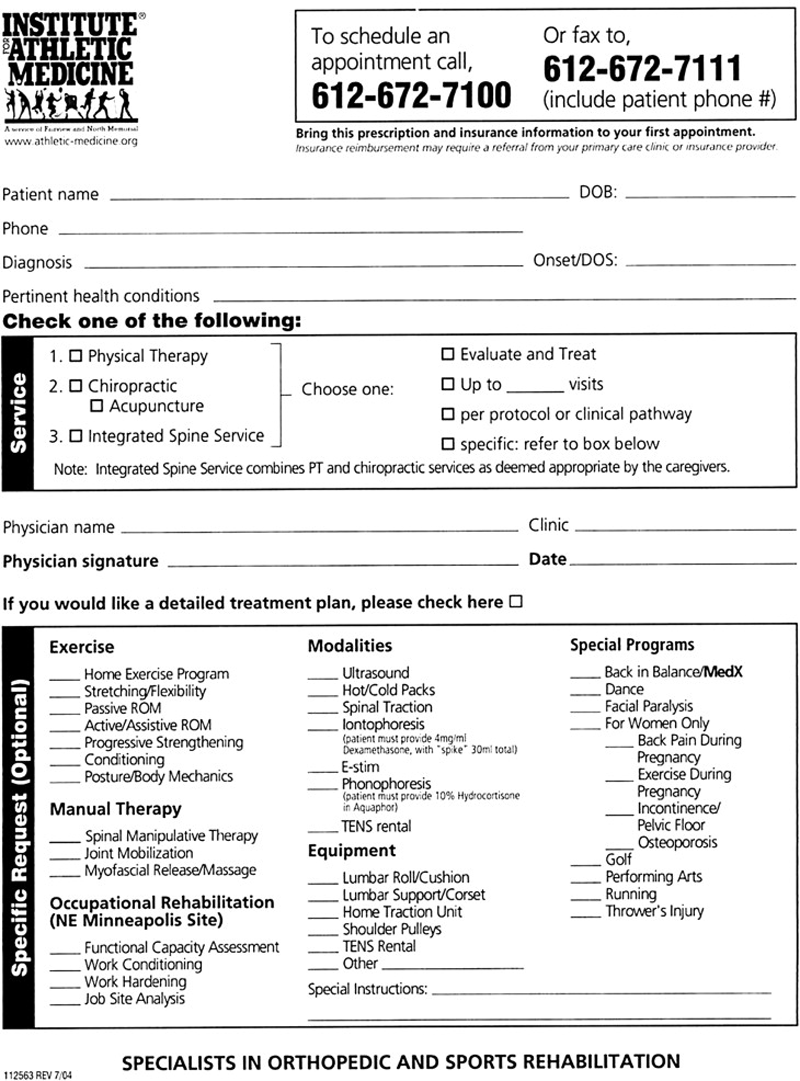

The fifth facilitator was the creation of integrated spine care. This referral service combines physical therapy and chiropractic services. In this model, the patient is evaluated by both providers. A short consultation between providers occurs, and an integrated treatment plan is derived. Patients can also be referred directly for independent chiropractic services. Figure 3 shows the referral form.

Barriers to Chiropractic Integration

Several barriers to inclusion, acceptance, and growth of the chiropractic service line in this private hospital system were identified. The first barrier relates to professional identity and the perception of chiropractic by other professionals. Ten years ago, hospital administrators were considering inclusion of chiropractic services; but there was concern over what type of chiropractic care would be included in the hospital system. The administrators and care givers in the system had differing perceptions and opinions about what chiropractors do and how they treat patients. Initially, some administrators and medical caregivers were concerned that chiropractors might provide unscientific care (eg, treat cancer, severe infections), not refer patients appropriately, or use inappropriate treatments that might put patients at risk. Their concerns were addressed through thoughtful and professional discussions. All of the chiropractors that were to be included would promote safe, evidence-based, collaborative, patient-centered evaluation and treatment approaches. Published clinical evidence was offered to back claims of safety and efficacy.

Initially, there were skeptics in the care system who were against chiropractic inclusion; some were vocal. In the end, rational, professional, patient-centered, and evidence-based presentations and discussions prevailed; and a chiropractic service line was added. Eventually, the model endorsed by the hospital system was that doctors of chiropractic would best serve as conservative spine health care specialists. The confusion by other providers about what chiropractors do and a lack of a unified professional identity appear to be barriers to integration.

A second barrier relates to the financial aspects of third-party payment for services rendered within the chiropractic service line. There are 3 main components under this barrier: variability of the chiropractic benefit, variability of reimbursement, and the inexperience of the hospitals billing department to manage chiropractic coding and billing. Each subbarrier will be addressed separately.

The medical and physical therapy professions that worked with this new chiropractic service line have a fairly consistent and universal commercial and public benefit set with local and national payers. This is not the case with the chiropractic. The hospital system struggled in managing the large variation of services covered under the many commercial and public health plans. Some plans, such as government payers, limit coverage to chiropractic manipulative therapy. This procedure is required to have a chiropractic subluxation or joint dysfunction diagnosis associated with the chiropractic manipulative therapy procedure codes. Under these public health plans, the patient is responsible for the costs of all associated evaluation and management services. The billing department, scheduling department, front office staff, and chiropractic staff require a unified and consistent message to communicate this noncovered service to the patient. Ten years later, this message is still not being conveyed with full efficiency to 100% of patients. To the best of the author's knowledge, no other profession is mandated to generate a working diagnosis under state statute; yet that state-mandated chiropractic benefit does not cover the evaluation and management service needed to generate the working diagnosis, which creates additional difficulty. In the early years of the chiropractic service line, some payers did not cover active care service codes, such as therapeutic exercise. To make things more confusing, some private health plans only cover acute musculoskeletal conditions. Eventually, a spreadsheet was created to attempt some level of management in benefit and fee schedule variability.

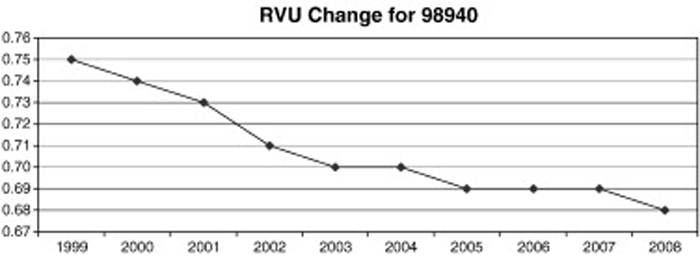

Figure 4 The third financial subbarrier relates to limited reimbursement for services under the scope of chiropractic. The hospital system noted a variation in the level of reimbursement for exercise instruction and some modalities (eg, ultrasound) when provided by a chiropractor vs a physical therapist. In some cases, this variation was substantially less under the chiropractic fee schedule for the exact same services. This limited level of reimbursement became a strong barrier to expand the often-requested service line in the hospital system. Most, if not all, fee schedule development by third-party payers is conducted using relative value units (RVUs) created from resource-based relative value scales set by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. These RVUs are then multiplied by conversion factors to create a fee for all procedure codes included in a fee schedule. In addition, a disturbing trend regarding the most likely billed procedure code by the chiropractic profession, 1-2 region chiropractic manipulative therapy, has occurred over the last 9 years. Figure 4 shows the downward trend regarding the RVU rating for this procedure code. If this decrease in the relative value is not offset by a favorable conversion factor, then reimbursement may decrease.

The creation of integrated care model systems may help control the increasing costs of health care. [12] Creating teams of caregivers around musculoskeletal conditions such as back pain is recognized in the literature. [2] In 2007, 37% of US hospitals offered CAM therapies, up from 26% in 2005. [13] Based on this, it appears that hospitals around the United States are adding CAM therapy providers on an increasing basis.

Evidence supporting the conservative management of spine-based conditions with manipulation is growing. A recent publication documented 6 guidelines and 42 randomized clinical trials recommending or investigating the effects of spinal manipulation or mobilization on chronic low back pain. [14] Spine conditions cause serious societal problems, and costs to treat spine pain continue to rise. In 2005, an estimated $85.9 billion was spent to treat back and neck problems. [15] According to a 2009 study, the incidence of chronic low back pain has increased from 4% in 1992 to 10% in 2006. [16] The chiropractic profession has a unique opportunity to participate with the private hospital industry as conservative spine care specialists to meet these needs.

According to the Institute for Alternative Futures, the chiropractic profession needs to develop greater integration into mainstream health care. [9] It is the author's opinion that further research is needed to determine if national and international hospital-based integration of chiropractic is cost effective at improving the health and well-being of the communities we serve.

Limitations

The limitations of this article include that this study was performed on a limited number of participants in one system. Some of the findings in this report are based upon the opinion of participants and perception of the author. Findings from this study may not necessarily apply to other regions and hospital systems.

Additional limitations revolve around business issues such as(1) the return on investment a hospital system may experience by having a chiropractic service line and

(2) a cost-benefit analysis of patients receiving care through chiropractic or other health care disciplines such as physical therapy, primary care, sports medicine, or medical orthopedics.In addition, no information was included regarding patient satisfaction or physician satisfaction with the addition of a chiropractic service line. Further research into such areas, such as return on investment, would contribute to the literature. Providing answers to such questions is critical in the era of health care reform.

Conclusion

This article describes the process of integrating chiropractic into one of the largest private hospital systems in Minnesota from a business and professional perspective and the results achieved once chiropractic was integrated into the system. This study identified barriers as well as key factors that facilitated integration of services. This article demonstrates that chiropractic care can be successfully integrated within a hospital system.

Survey of Providers Pertaining to

Appendix A.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Appendix A, Page 1

Appendix A, Page 1

References:

Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America.

Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century

Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001Porter, ME and Teisberg, EO.

Redefining health care: creating value-based competition on results.

National Academies Press, Boston, MA; 2006Haldeman S, Dagenais S.

A Supermarket Approach to the Evidence-informed Management of Chronic Low Back Pain

Spine Journal 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 1–7Meeker, W., & Haldeman, S. (2002).

Chiropractic: A Profession at the Crossroads of Mainstream and Alternative Medicine

Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (Feb 5); 136 (3): 216–227Erickson, S.

11th annual fees and reimbursement survey.

Chiropr Econ. 2008; 54: 26–39Haldeman, S and Dagenais, S.

Principles and practice of chiropractic. 3rd ed.

McGraw-Hill, New York; 2004 (112 p)Eisenberg, D, Kessler, RC, Foster, C, Norlock, FE, Calkins, DR, and Delbanco, DL.

Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs, and Patterns of Use

New England Journal of Medicine 1993 (Jan 28); 328 (4): 246–252Coulter, ID, Ellison, MA, Hilton, L, Rhodes, HJ, and Ryan, G.

Hospital-based integrative medicine: a case study of the barriers and facilitators

facilitating the creation of a center.

RAND corporation, Santa Monica; 2008The Institute for Alternative Futures

The Future of Chiropractic Revisited: 2005 to 2015

Alexandria, VA: (2005)Fairview.org [homepage on the internet].

Minneapolis, MN. [cited 2009 Apr 6]. Available from

http://www.fairview.orgCoulter, ID, Hurwitz, EL, Adams, AH, Genovese, BJ, Hays, R, and Shekelle, P.

Patients Using Chiropractors in North America:

Who Are They, and Why Are They in Chiropractic Care?

SPINE (Phila Pa 1976) 2002; 27 (3) Feb 1: 291–298Richard L. Sarnat, MD, James Winterstein, DC, Jerrilyn A. Cambron, DC, PhD

Clinical Utilization and Cost Outcomes from an Integrative Medicine

Independent Physician Association: An Additional 3-year Update

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (May); 30 (4): 263–2693rd Biannual Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Survey of Hospitals.

American Hospital Association health forum report.

American Hospital Association, Chicago; 2008Bronfort, G, Haas, M, Evans, R, Kawchuk, G, and Dagenais, S.

Evidence-informed Management of Chronic Low Back Pain

with Spinal Manipulation and Mobilization

Spine J. 2008 (Jan); 8 (1): 213–225Martin, BI, Deyo Ram Mizra, SK, Turner, JA, Comstock, BA, Hollingworth, W, and Sullivan, SD.

Expenditures and Health Status Among Adults With Back and Neck Problems

JAMA 2008 (Feb 13); 299 (6): 656–664Freburger, JK, Holmes, GM, Agans, RP, Jackman, AM, Darter, JD, Wallace, AS et al.

The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain.

Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169: 251–258

Return to ALL ABOUT CHIROPRACTIC

Return to INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE

Since 7-02-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |