Integration of Chiropractic Services in Military

and Veteran Health Care Facilities: A

Systematic Review of the LiteratureThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016 (Apr); 21 (2): 115–130 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Bart N. Green, DC, MSEd, Claire D. Johnson, DC, MSEd, Clinton J. Daniels, DC, MS

Jason G. Napuli, DC, MBA, Jordan A. Gliedt, DC, David J. Paris, DC

Naval Medical Center San Diego,

San Diego, CA,

USA National University of Health Sciences,

Lombard, IL, USA.

This literature review examined studies that described practice, utilization, and policy of chiropractic services within military and veteran health care environments. A systematic search of Medline, CINAHL, and Index to Chiropractic Literature was performed from inception through April 2015. Thirty articles met inclusion criteria. Studies reporting utilization and policy show that chiropractic services are successfully implemented in various military and veteran health care settings and that integration varies by facility.

Doctors of chiropractic that are integrated within military and veteran health care facilities manage common neurological, musculoskeletal, and other conditions; severe injuries obtained in combat; complex cases; and cases that include psychosocial factors. Chiropractors collaboratively manage patients with other providers and focus on reducing morbidity for veterans and rehabilitating military service members to full duty status. Patient satisfaction with chiropractic services is high. Preliminary findings show that chiropractic management of common conditions shows significant improvement.

Keywords chiropractic, military, medicine, hospitals, veterans, military personnel

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Musculoskeletal disorders account for nearly 7% of the total disability-adjusted life years globally, which, according to the recent Global Burden of Disease studies, is the fourth greatest burden on population health. [1] Low back pain is the leading cause of disability, estimated to be responsible for 83 million years lived with disability, [2] closely followed by neck pain. [1] Military service members (MSM) and veterans share this burden. In this special population, musculoskeletal injuries are often categorized as either battle or nonbattle injuries. [3–5] Battle-related musculoskeletal injuries include those that arise from small arms fire, missile strike, exposure to explosive devices, and other injuries. These exposures often result in fracture, dislocation, amputation, gunshot wounds, significant soft tissue injuries, and related harms. Nonbattle injuries are those that most people suffer from, such as sprains and strains that occur as part of regular work; such musculoskeletal problems affect the performance of MSMs across a wide spectrum of occupational specialties. [6] Back pain is one of the leading musculoskeletal causes of disability in MSMs returning home from conflicts in Southwest Asia. This influx of patients is leading to a steady increase in the prevalence of back pain among United States veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. [4, 7]

Veterans who sustain musculoskeletal injuries during their military careers may continue to suffer morbidity associated with these disorders and require care. MSMs and veterans with musculoskeletal problems may be referred for chiropractic services that are integrated into military and veteran health care facilities. For example, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) have adopted a guideline [8] to help clinicians manage the complexity of back pain. This guideline includes the use of spinal manipulation and therapeutic exercise, often provided by chiropractors working in VA or US Military Health System (MHS) facilities. [9]

The integration of doctors of chiropractic into the US MHS under the DoD and through VA is relatively new and has witnessed rapid growth.10 Chiropractic care has been offered as a health care benefit within the MHS since 1995, [10, 11] is currently available at 65 military treatment facilities across the United States, [12] and is considered fully implemented by the DoD. [13] Although VA offered limited chiropractic services on a fee basis for several years, VA began offering integrated chiropractic services in VA facilities in 2004. [14] This occurred after enactment of 3 key public laws, the Veterans Millennium Health Care and Benefits Act, [15] the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care Programs Enhancement Acts of 2001, [16] and the Veterans Health Care, Capital Asset, and Business Improvement Act of 2003. [17] Currently, chiropractic care is available at more than 51 VA facilities, [18] and continues to expand. The inclusion of chiropractic care inmilitary and veteran health centers in other countries is sparsely reported, with Canada being the only other country reporting such services. [19]

Our previous review20 reported on various aspects of inclusion of chiropractic services within military and veteran health care systems. However, few articles were available at the time and we recommended that more research was needed to produce reproducible and robust summaries. The previous article identified needs and potential future research in veteran and military chiropractic care. In particular, it was noted that more publications were needed in the following areas: how often chiropractic services were utilized; if patients receiving chiropractic care reported better outcomes; more studies from countries outside of the United States; descriptions of structure of care; processes of care; provider workload; cost effectiveness. [20] It has been 20 years since chiropractic was introduced into the MHS and more than 10 years since the inclusion of chiropractic services in VA. Six years have passed since completion of the previous study. Thus, we felt it was an appropriate time to revisit the literature to identify what new information is available to describe chiropractic inclusion in military and veteran health care internationally. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to provide an updated review of the literature that describes practice, utilization, policy, and research of chiropractic services within military and veteran health care environments worldwide and, based on these findings, to offer suggestions for increasing research capacity within these health care settings.

Methods

Search Strategy

Table 1 The lead author (BNG) performed PubMed and Index to Chiropractic Literature searches at their respective web sites and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature with full text was searched using EBSCOhost Web. The search excluded articles that were cited in MEDLINE to avoid duplication of the PubMed search to the degree possible. Searches for all databases were from the starting dates of each through April 2015. We combined the term chiropractic with a variety of terms relevant to the topic. Complementary medicine and alternative medicine were also combined with other terms to broaden the search and capture all relevant publications (Table 1). We identified additional articles by searching the references found in the articles retrieved, searching our personal libraries, and by contacting authors who have published in this area.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

All languages and all types of study designs from any country were included in the search. Articles from non-peer-reviewed sources (eg, trade magazines), and other nonscholarly sources, and writings not specific to the reported use of chiropractic or of chiropractic in military or veteran facilities were excluded. Abstracts of conference proceedings were not included due to the high rate of conference presentations that never reach full publication. [21, 22] Articles were considered for final inclusion if they described or studied chiropractic care within active duty or veteran health care environments. Studies or descriptions of care of MSMs or veterans outside of active duty or veteran health care environments were not included (eg, care of a veteran at a private practice clinic).

Methods of Review

The search process was conducted by the primary author; coauthors were asked to contribute citations with which they were familiar but which might be missing from the formal search. Citations were screened by the primary author for inclusion by reading the title and abstract for each citation. Abstracts of the citations that obviously or possibly met the review criteria were saved. The full papers of each abstract were retrieved and all authors independently reviewed each article to verify that it met the inclusion criteria. All authors reached consensus to include or exclude the articles. Articles that did not meet the criteria were discarded and a note was made as to why they were excluded. Once an article was included, the citation, study design, principal findings, and other pertinent notes were logged in a summary table. Quality scoring was not performed as the articles reviewed were not homogenous.

Results

Figure 1 From the search engines, there were 3,950 citations for the full search (Table 1), including 988 from the first article and 2962 new citations published since June 2009. As shown in Figure 1, there were 3,860 articles screened out as irrelevant, leaving 90 relevant or potentially relevant articles. Of these, 46 were published since the 2,009 review, including 41 from literature searches and 5 found by the contributing authors. After applying the exclusion criteria, 17 new articles [10, 18, 20, 23–36] were acceptable for review and added to the 13 articles [19, 37–48] reviewed in the original study. Thus, the total number of articles included in this updated review is 30. [10, 18–20, 23–48]

Inclusion of Chiropractic in Military and Veteran Health Care

Table 2

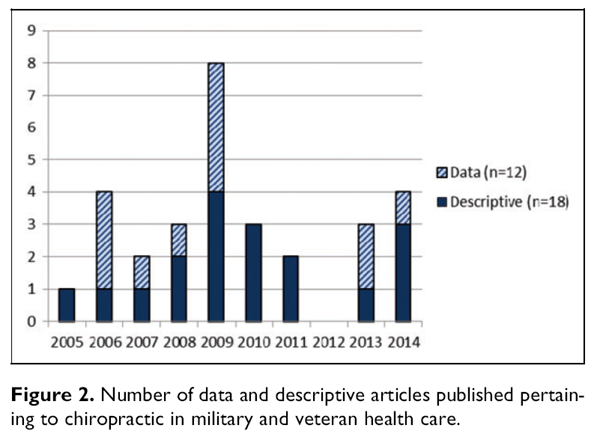

Figure 2 Integration of chiropractic care into military or veteran health care systems has been described in 3 systems: MHS, VA, and Canadian Forces. All but one of the articles are from the United States. Table 2 provides a breakdown of the study designs reported. Figure 2 shows the number of articles published presenting data, typically representing more complex research designs, and those that are entirely descriptive. A summary of the included articles is presented in Table 3.

Articles Excluded

Sixty articles were excluded according to the selection criteria (Table 4 and Figure 1). Reasons for exclusion are presented in Table 4. The most common reason articles were excluded was that they described the use of complementary and alternative medicine modalities among military or veteran beneficiaries, but included no breakdown of the utilization of chiropractic care from the larger set of complementary and alternative medicine practices and did not distinguish if chiropractic was provided in the military or veteran setting. Another common reason for exclusion was that a study was not clear whether the chiropractic care included in the complementary and alternative medicine practices was provided at a designated military or veteran health care facility or if chiropractic care was obtained from outside sources. For these studies, we contacted the authors of these articles in question for definitive answers, all of whom responded to our inquiry and provided clarification.

Table 3 + 4 Please refer to the Full Text article

A few articles with apparent US military/veteran and chiropractic relevance were excluded and explanation for their exclusion is provided here. A commentary [49] predated the inclusion of chiropractic services in the US MHS and was excluded because it was a theoretical article, hypothesizing what might occur should chiropractic services be included in military care and did not discuss actual working settings. An article [50] was excluded because it did not involve the use of chiropractic care within the VA setting but critiqued chiropractic care provided as part of a pilot fee-for-service model used by VA and this care was provided outside of the VA system. A randomized trial involving chiropractic care with veteran patients [51] was excluded because, while VA patients were included in the study, the setting primarily was a mixture of non-VA physical therapy and chiropractic clinics in the local community and the sample was drawn from a mix of VA and non-VA patients. An article was excluded for similar reasons; the article was a study proposal that described the study design for a trial in both VA and non-VA facilities but there were no actual subjects yet recruited to the study. [52] An article that was excluded was a historical commentary [53] that discussed the use of chiropractic care in aviation. While there was mention of chiropractic care in selected military environments, the material was mostly taken from articles that were already covered in this review as primary sources; thus, including this article would have duplicated findings.

Discussion

Practice, Utilization, Policy, and Research

Overall, the current literature on chiropractic services within military and veteran health care environments worldwide gives us a glimpse into current practices. Doctors of chiropractic are fully integrated into both the MHS and VA health care settings located in various geographic regions within the United States and in 3 MHS locations outside of the United States. Chiropractic practitioners manage common musculoskeletal conditions, but also see unusual cases that are worth reporting in the literature. These doctors of chiropractic manage complex cases, especially patients with musculoskeletal conditions, and these often include psychosocial factors. Common conditions include back and neck pain, but patients with more severe injuries, such as injuries obtained in combat, are also managed by chiropractors in these integrated settings. Chiropractors manage patients with a team of other providers and they focus on reduction of morbidity for MSMs and veterans and return to active duty in military settings. As is consistent with other literature, patient satisfaction with chiropractic services is high in MHS and VA settings. Some preliminary research findings show that chiropractic management of common conditions for VA and MHS patients show significant improvement compared to other types of care.

Studies reporting utilization and policy show that chiropractic services can be implemented in various settings and how chiropractors are integrated may vary by facility. Typically, the doctor of chiropractic collaborates with other providers in the management of cases and is referred cases from medical providers and also refers to other providers and specialists. Chiropractic practitioners function in various departments including sports medicine, physical therapy, pain care, physical medicine and rehabilitation, orthopedics, and stand-alone departments.

Currently, research related to chiropractic is being done inmilitary and veteran health care environments. However, the designs are diverse and without an apparent direction as it appears that there is no published agenda for chiropractic research in these settings. Publications are mainly being authored by individual chiropractic providers who are performing studies within their practice settings. The narrow pool of authors limits the scope and design of the studies.

First Publications in Topic Domains

Proposals to integrate chiropractic services into veteran or military health services began more than 60 years ago. [54–56] Efforts in the 1940s and early 1950s proposed a bill tomake eligible for appointment in the medical service, Department of Medicine and Surgery, Veterans’ Administration, any person who holds the degree of doctor of chiropractic from a college or university approved by the Administrator of Veteran’s Affairs, who is licensed to practice chiropractic in one of the States or Territories of the United States. [57]

After many decades, VA conducted the Chiropractic Services Pilot Program Evaluation study (SDR #86-09) as a pilot program to look at providing chiropractic services on a feefor- service basis, but not in an integrated form. [50] It is believed that the inclusion of chiropractic into MHS in 1995 was the first integration of chiropractic services into a military or veteran health care system. However, it would be 11 years before any literature emerged from this milieu. VA began integrated chiropractic services in 2004 with publications in the peer-reviewed literature commencing in 2005.

In 2005, Dunn [38] authored the first article reporting on any feature of chiropractic care included within VA. This article described an internship at one VA facility. In 2006, Dunn et al [40] authored the first article to describe the dynamics and demographics of a VA chiropractic clinic. The first article reporting on any aspect of chiropractic in MHS was published by Green et al in 2006 and was a case report of chiropractic care for a jet pilot with low back pain. [41] Shortly thereafter, Dunn compared variables of career success between interns that participated in a rotation at a naval health clinic and those that did not. This article was the first to describe any aspect of chiropractic student training in MHS. [39]

Lisi and colleagues published the first system-wide description of VA chiropractors and chiropractic clinics in 2009. [25] Lisi also authored the first report of chiropractic services for veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans in a VA facility. [27] The first experimental design evaluating chiropractic care for VA patients was a randomized clinical trial by Dougherty and colleagues, which we discuss in more detail later. [34]

While a variety of case reports on patients in MHS have been published, larger descriptive or experimental studies are sparse. The first experimental study investigating chiropractic care in MHS is a randomized controlled trial by Goertz and colleagues that evaluated low back pain outcomes for MSMs, discussed in more detail later. [32]

The only other country that has reported on the use of chiropractic care in military or veteran facilities is Canada. Chiropractic services were offered at one Canadian forces facility in Halifax, Nova Scotia, as a pilot project for several years. The authors reported that chiropractic referrals were primarily for axial spine pain and that there was high satisfaction among patients and referring providers. The majority of respondents (94% of military personnel and 80% of referring physicians) reported satisfaction with chiropractic services. [19]

Integration of Chiropractic in MHS or VA Facilities

Several articles describe the integration of chiropractic services in VA and description of this integration has evolved since Dunn et al’s initial descriptions of the chiropractic care consultation system at one facility. [40, 45] In a cross-sectional survey representative of all VA doctors of chiropractic, Lisi et al [25] reported the prevalence of common problems referred for chiropractic care, with back and neck pain comprising the bulk of consults. They also described the service lines referring patients to chiropractic care, most of which came from primary care, and the services to which chiropractors typically made referrals. Chiropractic provider characteristics were also reported, including demographics, employment agreements, the level of integration of the chiropractor in the facility, staffing, and compensation. Patient evaluation procedures were consistent across providers with more variation in patient care reported. Participation in research, particularly funded research, was not prevalent among the sample (18% often participating), where training chiropractic students was more common (39% often participating).

Other research further investigated chiropractic integration into VA through the use of a stakeholder and document evaluation model. [18] In this study, 114 people with various levels of involvement in VA chiropractic services were interviewed, including nonchiropractic clinicians, patients, senior and middle-level administrators, chiropractors, support staff, and others. The authors also evaluated 75 policy and procedure documents. It was found that a wide variety of processes were used among the VA sites that were queried to implement chiropractic services. Numerous clinical structures were employed, ranging from integration of chiropractic services within established departments of physical medicine/rehabilitation to spinal cord services and from colocating chiropractic providers with other health care providers to establishing chiropractic services in isolation. Types of conditions, referring service lines, a trend toward increased utilization, and elements of patient evaluation and management were consistent with the earlier national survey. [25] However, wide variation in the utilization of chiropractic services was reported across the 7 sample sites.

How chiropractors are integrated into MHS facilities is described less frequently than in VA. There are no articles that provide cross-sectional data on chiropractic integration nationally in MHS and no studies to report practice utilization or variation in care. A glimpse of integration is afforded by Dunn, Green, and Gilford’s system analysis of MHS and VA chiropractic services. They provide a general overview of similarities and differences between VA and MHS chiropractic services in the areas of programmatic growth, leadership, employment status of providers, clinician responsibilities, patient access, patient demographics, academic pursuits, and research.10 The only other article that describes the integration of chiropractic services into MHS is a description of interdisciplinary care offered at Naval Medical Center San Diego’s comprehensive complex casualty care center. [24] This descriptive report is also the only article that describes the integration of chiropractic services into the care of combat-injured troops.

Scope of Practice

No articles provided reviews of policies codifying the scope of practice for chiropractors in military or veteran health care systems. Perhaps the best description of chiropractic scope of practice in MHS and VA is offered by Dunn, Green, and Gilford, as follows:The primary duty is to provide comprehensive chiropractic services as is commonly taught at accredited chiropractic colleges and in further specialty training. Chiropractors in both systems are allowed to use the manipulative techniques that they feel are appropriate for the needs of the patient, as well as other procedures, such as therapeutic modalities and rehabilitation. [10]

Several articles, however, provided descriptions of chiropractic care indicating that chiropractors in the DoD and VA employ a broad range of treatment procedures that include:

spinal manipulation/mobilization in a variety of forms, [23, 25, 27–32, 35, 36, 44, 45, 47, 48]

extraspinal manipulation/mobilization, [41, 45]

therapeutic exercise, [23,25, 27–32, 35, 36, 41, 44]

passive stretching, [41, 48]

muscle energy techniques, [28, 41]

cryotherapy, [32, 45]

thermotherapy, [32, 41]

soft tissue therapy, [25, 27–30, 32, 36, 41, 47]

ultrasound, [45]

physical modalities, [25, 27]

orthoses, [25]

acupuncture, [25]

nutrition, [25] and

patient education. [25, 27, 30, 32, 35, 41, 44]

Chiropractic Care Outcomes and Effects of Comorbidities

Outcomes of chiropractic care and the potential confounding or moderating effects of various comorbidities in veteran patients are reported with greater frequency than in the initial literature review. Dunn and Passmore first reported a potential association between spine pain and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in VA chiropractic service in 2008, reporting that 16% of patients had PTSD. [45] In a follow-up study published 1 year later, the authors showed that veterans with PTSD had worse spine pain outcomes following care than veterans without PTSD. These findings suggest a treatment modifying effect of PTSD on chiropractic care for veterans with back or neck pain. [47]

Outcomes of chiropractic care in back and neck pain patients are reported from several VA facilities. The first of these studies showed that with an average number of 9 chiropractic treatment visits, the average improvement in pain ratings and Back Bournemouth Questionnaire scores indicated approximately 37% and 54% improvement, respectively. [29] For veterans with neck pain the average improvement in pain ratings and Neck Bournemouth scores indicated approximately 43% and 31% improvement, respectively. [30]

Chiropractic outcomes in an observational study of veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom by Lisi [27] were similar to those reported in older veterans in Dunn et al’s study. [47] In younger veterans, comorbid PTSD and traumatic brain injury were frequently reported and suspected to alter patient response to care. [27]

Dougherty et al conducted a pragmatic randomized clinical trial of spinal manipulative therapy for veterans receiving chiropractic care for low back pain at VA facilities. [34] This study focused on older veterans (65 years of age or older), allocated them to either a spinal manipulation or a sham intervention group, and no other interventions were performed aside from providing patients a standardized patient education booklet. Both groups demonstrated significant improvements in pain and disability scores at 5– and 12– week follow-ups and there was no difference in the reporting of adverse events between groups. However, at 12 weeks, while the average pain scores were not significantly different, the spinal manipulation group had improved disability scores over the sham group.

The only study to report outcomes of chiropractic care in a group of MSMs is one reported by Goertz and colleagues. [32] This pragmatic randomized comparative effectiveness study reported on MSMs between the ages of 18 and 35 years who had low back pain for 4 weeks or less. Participants were allocated to either a standard medical care group or to a group that received standard medical care and chiropractic care. After treatment, adjusted mean scores on the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, mean numerical rating scale pain scores, and adjusted mean back pain functional scale scores were significantly improved for the group receiving both standard medical care and chiropractic care.

Articles on Education and Training in VA or MHS Facilities

Chiropractic externships exist in both MHS and VA and residencies are available in VA. Three studies report on training programs in these environments and all of these articles [38, 39, 42] were summarized in our initial 2009 review. [20] Summarily, Dunn reports on VA externship at one facility, [38] provides a comparison of VA academic affiliations, programs, facilities, and other parameters at 4 VA hospitals, [42] and the final study found no difference in a variety of career success variables between externs who participated at 1 of 2 MHS externships at US Navy hospitals. [39] No new education research has been reported since 2007.

Descriptive Clinical Studies

A variety of case reports and case series have been published about patients receiving chiropractic care in both MHS and VA. All of the cases focus on the chiropractic management of musculoskeletal conditions. Table 3 describes these studies in more detail.

Growth of the Literature

In our first review of this literature in 2009, there were 13 articles to review. [20] These articles had been published over a period spanning decades. In the present review, an additional 17 articles were published in the past 6 years, representing a growth in the interest of research pertaining to chiropractic care within veteran or military integrated health care delivery systems. It is noted that there are more articles published on chiropractic care in VA (n = 16) than in MHS (n = 10) and few reports from both systems (n = 4). While the increase in publications in this area of inquiry is positive, the total number of articles on this topic is still very small and concerning to the sustainment of chiropractic services in these environments. There is still little evidence to inform practice and policy; continued support for research pertaining to chiropractic care in military and veteran health care systems should remain high on the agendas of organizations with interests in this area.

Authorship

The bulk of the articles (20 of 30, 70%) were led by 3 authors: Dunn (11 articles), Green (6 articles), and Lisi (3 articles). The remaining principal authorships were spread across 10 other authors. Dunn, Green, or Lisi served as the lead author or cocontributor on a total of 87% (26/30) of the articles included in this review. This indicates a narrow pool of authors who are contributing to research in this area. Greater diversification of principal and coauthors will be necessary if this evidence base is to continue to grow.

Levels of Evidence

Varying levels of evidence of the literature have increased over time. In the first review, all of the research was descriptive and ranked as levels 4 and 5 on the Oxford Centre for Evidence- Based Medicine levels of evidence. [58] With the addition of the 17 articles for this review, there is inclusion of some level 2 and level 1 research studies. This finding is promising as it may mean that research in this area is advancing.

Areas for Further Inquiry

Further reports of outcomes of chiropractic care in VA and MHS are much needed. Trials that evaluate comparative effectiveness are particularly important, as they provide data on which therapies provide the best outcomes for a given condition. To date, there is only one such trial. [32] In this era of evidence-based health care and cost containment, comparative trials may help gain insight into cost-effectiveness and improved outcomes. Utilization and practice parameters on MHS clinics have yet to be reported; a profile of even one MHS chiropractic clinic is yet to be reported.

The authors have spoken with people from a variety of countries about the use of chiropractic care in military and veteran environments in countries outside of the United States. However, there are no reports in the literature about these services and reports would aid in providing comparisons among different populations of MSMs and veterans and potentially stimulate research collaborations.

With the publication of studies indicating significant effects of comorbidities on chiropractic outcomes, further studies should investigate which variables are associated with outcomes, such as spine pain, in MSMs and veterans receiving chiropractic care. Cross-sectional studies with magnitudes of association between suspected variables and spine pain could be conducted. Clinical trials should be adjusted to potentially control for influential comorbidities such as PTSD or traumatic brain injury, as well as the effect of deployment to combat theater.

Creating clinical prediction rules for the management of nonspecific spine pain, disc pathology, stenosis, spondylolisthesis, and postsurgical pain, may be fruitful research endeavors with immediate practice relevance.

With this literature growing, it will be desirable in the future to pool data for meta-analyses. However, to do so will require that studies conducted now conform to standardized reporting guidelines. We strongly urge current and future researchers to report their findings using reporting methodologies such as CONSORT, [59] STROBE, [60] PRISMA, [61] and others.

Need for Increased Research Capacity

More resources, authors, and advanced studies are greatly needed. Evidence-based practice relies on the higher tiers of evidence to inform practice and more evidence for practice is needed in these military and veteran environments. It is still unknown whether or not chiropractic care is effective in these health care environments, for what conditions this care might be effective, if it represents a good expenditure of funds, and how chiropractic outcomes may be affected by comorbidities. Training chiropractors in military and veteran health care systems how to do research, allocating time for research to be performed, funding the research, and collaboration need to be remedied as much now as they did in our first review.Training. As we addressed previously, the majority of chiropractors in MHS and VA facilities do not have training as researchers or authors. If studies are to continue, practitioners need to be trained in the methods of research and scholarly writing and develop mentorships with experienced authors at their facilities. As incentives, health care facilities could allocate part of provider evaluation to research productivity and place priority on research skill sets when evaluating potential candidates as chiropractic providers in these systems. Training in grant writing remains a necessity. As we discussed in our previous review, it is important to secure funding to conduct more complex studies or to secure experienced researchers who can successfully execute advanced research designs. Training in research methods and writing are also necessary to increase the pool of writers contributing to this area of inquiry. While the 30 articles in this review contained several different primary authors, it is concerning that just 3 people served as lead authors on 70% of the articles. The same authors were cocontributors on 12 articles. With these authors well into their mid-careers, it is clearly important that effort needs to be placed on training future researchers in MHS and VA.

Time. Sufficient time needs to be set aside for research activities. Most chiropractors are hired primarily as clinicians to see patients and the majority, if not all, of the practitioner’s professional workload is dedicated to duties relating to clinical concerns. Thus, allocating research time to the position description and evaluating research output as part of the performance evaluation system seems imperative. Publication and scholarly activity are elements of the VA Chiropractic Qualification Standards utilized for rank and promotion. Thus, this system offers incentive for chiropractors to engage in the research effort. It will require significant discussion and change to current MHS practices to allocate research time and productivity to chiropractic position descriptions, or to have such changes made on a local level on a case-by-case basis.

Funding. Funding is essential to successfully complete large and complex research studies. As has been shown with some of the articles in this review, intramural funding is available at some facilities and grants from within federal agencies have been secured to conduct recent research. However, attracting the interest of seasoned, nonchiropractic researchers is likely still influenced by the availability of funding. In short, researchers and outside institutions are not likely to dedicate research efforts and institutional resources if there are no positive benefits for them. External funding from government and private foundations must continue to be a priority for research to continue.

Collaboration. As research interests and skill sets of chiropractic researchers in military and veteran setting continue to evolve, it is likely natural for larger and more complex research designs to be desired. Such studies require the time, money, personnel, and other resources to which most clinicians do not have access. Most MHS and VA hospitals have departments of research and investigation, institutional review boards, medical writers, statisticians, and other assets available to assist in the research effort. Chiropractic providers in these systems need to access these resources in their research efforts. Furthermore, collaboration with universities can provide the means necessary to implement and complete complex endeavors, such as clinical trials and case-control studies. Such collaborations will likely stimulate more research questions that can lead to improved working relationships in the future.

Use of Chiropractic and Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Among Military and Veteran Patients

Complementary and alternative medicine can be defined as [62] "interventions not taught widely at US medical schools or generally available at US hospitals." Popular complementary and alternative medicine practices include herbal remedies, yoga, acupuncture, and chiropractic, among many others. [63] In the United States, chiropractic care is used by an estimated 8.5% of the population, as reported in a recent analysis of a large representative sample. [64] As one of the most popular providerbased complementary and alternative medicine practices in the United States, chiropractic care accounts for approximately 190 million office visits per year and about 30% of all complementary and alternative medicine practitioner visits. [65] Since US MSMs and veterans represent a subpopulation of Americans it is not surprising that complementary and alternative medicine use is widely reported and may be increasing.

In 2007, Smith and colleagues found that one third of US Navy and Marine Corps personnel utilized at least one form of complementary and alternative medicine, including chiropractic care. [66] When reviewing the health care use of a large military cohort of more than 86 000 respondents, Jacobson et al reported in 2009 that 41% of MSMs used some type of complementary and alternative medicine, with 30% using at least one provider-based form of complementary and alternative medicine therapy and 27% using at least one selfprovided complementary and alternative medicine therapy. [67] In 2013, Goertz et al reported increasing rates of complementary and alternative medicine use in a large representative sample of MSMs showing that complementary and alternative medicine use is higher among MSMs than the civilian US population with a prevalence of 45%. [68] Most recently, in 2014 Davis and colleagues reported that complementary and alternative medicine was used by 37% to 46% of active duty and reserve MSMs in the United States. [69] Collectively, these articles represent a 10% increase in the prevalence in use of complementary and alternative medicine by MSMs in an 8-year time period.

VA has acknowledged the increased use of complementary and alternative medicine by veterans and the need to incorporate complementary and alternative medicine practices for various disorders and wellness. [70] Driven by both patient expectations [70] and reaction from veteran health facilities, [71] the use of complementary and alternative medicine in veterans is increasing. It is known that veterans who use VA health care are more likely to be complementary and alternative medicine users. [72] Complementary and alternative medicine use has been reported by 27% and 50% of veterans in 2 separate studies [73, 74] and as high as 82% in a recent article by Denneson et al, where the most frequently used therapy was chiropractic care in 56% of veterans surveyed. [75] Reinhard et al performed a secondary analysis of data from veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom/ Operation Iraqi Freedom. This survey includes questions about 12 preselected types of complementary and alternative medicine. They found that approximately 15% of these veterans used one of the forms of complementary and alternative medicine, with chiropractic care being used by approximately 12% of the total sample. [72]

Authors have hypothesized that reasons for the increased use of complementary and alternative medicine may be because patients were not receiving adequate clinical results with other forms of care, [75, 76] that complementary and alternative medicine services may be a useful method for managing pain without the use of opioid pain medications, [77] exposure to a wide variety of cultural and health practices as a result of military service, [78] and that veterans have poorer health status than their civilian counterparts. [72] Specifically with relation to veterans, Dorflinger and colleagues have noted that VA has implemented a Stepped Care Model of Pain Management that involves increasing nonopioid multimodal pain care and that consults for chiropractic care increased as this model was implemented at one VA facility. [77]

Limitations

This study is limited by the literature available for review. While there has been growth in this area of inquiry in just the past few years, there are still few articles to review and therefore caution should be used in drawing generalizable conclusions from the results. It is possible that unpublished documents exist pertaining to chiropractic services in military and veteran health care. However, this article reports only on literature that is publicly available. We excluded conference abstracts from the study because many conference presentations are never published. Thus, we may have missed some accounts in the "grey literature." However, we feel that our inclusion and exclusion criteria justify this choice. As it was outside of the scope of this research, we did not review each of the policies that guide the implementation, procedures, and protocols at various military and veteran facilities. This would make an interesting study in the future.

Conclusion

Our review of the literature revealed 30 studies pertaining to chiropractic care integrated into military or veteran health care systems. Chiropractors work within a multidisciplinary health care environment; manage neurological, musculoskeletal, and other conditions; work collaboratively with primary care providers; and have high levels of patient satisfaction. Preliminary findings show that chiropractic management of common conditions for VA and MHS patients show significant improvement. Although there is an increasing body of literature, this study points to the need for additional high-quality documentation. In order to develop a process for evaluating chiropractic services in military and veteran integrated health care delivery systems, more published research is needed. We suggest that in order to develop a greater literature base, additional training, time, funding, and collaboration are needed.

Authors' Note

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at Naval Medical Center San Diego, Bay Pines VA Healthcare System, and VA Northern California Health Care System.

Author Contributions

Concept development: BNG, CDJ, CJD. Design: BNG, CDJ. Supervision: BNG, CDJ. Data collection/processing: BNG, CDJ. Analysis/ interpretation: BNG, CDJ, CJD, JGN, JAG, DJP. Literature search: BNG. Writing: BNG, CDJ, CJD, JGN, JAG, DJP. Critical review: BNG, CDJ, CJD, JGN, JAG, DJP.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: BNG, CDJ, JGN, and DJP received indirect support from their institutions in the form of computers, workspace, and time to prepare this article. BNG is employed as a doctor of chiropractic to provide chiropractic services to the US Navy. JGN and DJP are employed as doctors of chiropractic by the Veterans Affairs. CDJ is the spouse of a doctor of chiropractic to provide chiropractic services to the US Navy.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References:

March L, Smith EU, Hoy DG, et al.

Burden of Disability Due to Musculoskeletal (MSK) Disorders

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28:353-366.Buchbinder R, Blyth FM, March LM, Brooks P, Woolf AD, Hoy DG.

Placing the global burden of low back pain in context.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:575-589.Clark ME, Bair MJ, Buckenmaier CC 3rd, Gironda RJ, Walker RL.

Pain and combat injuries in soldiers returning from Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom: implications for research and practice.

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:179-194.Gironda RJ, Clark ME, Massengale JP, Walker RL.

Pain among veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom.

Pain Med. 2006;7:339-343.McKee KT Jr, Kortepeter MG, Ljaamo SK.

Disease and nonbattle injury among United States soldiers deployed in Bosnia-Herzegovina during 1997: summary primary care statistics for Operation Joint Guard.

Military Medicine 1998;163:733-742.Feuerstein M, Berkowitz SM, Peck CA Jr.

Musculoskeletalrelated disability in US Army personnel: prevalence, gender, and military occupational specialties.

J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39: 68-78.Sinnott P, Wagner TH.

Low back pain in VA users.

Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1338-1339.US Department of Veterans Affairs.

VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain (2017)

Washington, DCChou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr., Shekelle P, Owens DK:

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline

from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 478–491Dunn AS, Green BN, Gilford S.

An Analysis of the Integration of Chiropractic Services Within

the United States Military and Veterans' Health Care Systems

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 749–757Birch & Davis Associates.

Final Report: Chiropractic Health Care Demonstration Program.

Falls Church, VA: Birch & Davis Associates; 2000.Defense Health Agency.

Designated locations for the chiropractic health care program.

Falls Church, VA: Defense Health Agency.

http://www.tricare.mil/Plans/SpecialPrograms/ChiroCare.aspx

February 28, 2015.Assistant Secretary of Defense.

Health Affairs Policy 07-028.

Washington, DC: Department of Defense; November 9, 2007.Department of Veterans Affairs.

Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care Programs Enhancement Act of 2001

Public Law 107–135 — January 23, 2002Department of Veterans Affairs.

Veterans Millennium Health Care and Benefits Act

Public Law 106–117 — November 30, 1999Department of Veterans Affairs.

Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care Programs Enhancement Act of 2001

Public Law 107–135, Section 204.Veterans Health Care,

Capital Asset, and Business Improvement Act of 2003. Pub. L. No. 108-170, Section 302.

http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-108publ170/pdf/PLAW-108publ170.pdf

Accessed November 27, 2015.Lisi AJ, Khorsan R, Smith MM, Mittman BS.

Variations in the Implementation and Characteristics of Chiropractic Services in VA

Medical Care 2014 (Dec); 52 (12 Suppl 5): S97–104Boudreau LA, Busse JW, McBride G.

Chiropractic Services in the Canadian Armed Forces: A Pilot Project

Military Medicine 2006 (Jun); 171 (6): 572–576Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ, Tucker J.

Chiropractic Practice in Military and Veterans Health Care:

The State of the Literature

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2009 (Aug); 53 (3): 194–204Scherer R, Langenberg P, von Elm E.

Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):MR000005.Dumville J, Petherick E, Cullum N.

When will I see you again? The fate of research findings from international wound care conferences.

Int Wound J. 2008;5:26-33.Dunn AS, Baylis S, Ryan D.

Chiropractic management of mechanical low back pain secondary to multiple-level lumbar spondylolysis with spondylolisthesis in a United States Marine Corps veteran: a case report.

Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2009;8:125-130.Goldberg C.K., Green B., Moore J.

Integrated Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation Care at a Comprehensive

Combat and Complex Casualty Care Program

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 781–791Lisi, AJ, Goertz, C, Lawrence, DJ, and Satyanarayana, P.

Characteristics of Veterans Health Administration Chiropractors and Chiropractic Clinics

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009; 46 (8): 997–1002Lillie GR.

Resolution of Low Back and Radicular Pain in a 40-year-old Male United States Navy

Petty Officer After Collaborative Medical and Chiropractic Care

J Chiropractic Medicine 2010 (Mar); 9 (1): 17–21A.J. Lisi,

Management of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom

Veterans in a Veterans Health Administration Chiropractic Clinic: A Case Series

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010; 47 (1): 1–6B.N. Green, A.S. Dunn, S.M. Pearce, et al.,

Conservative Management of Uncomplicated

Mechanical Neck Pain in a Military Aviator

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2010 (Jun); 54 (2): 92–99Dunn, AS, Green, BN, Formolo, LR, and Chicoine, D.

Retrospective Case Series of Clinical Outcomes Associated with

Chiropractic Management For Veterans With Low Back Pain

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011; 48 (8): 927–934Dunn AS, Green BN, Formolo LR, Chicoine DR.

Chiropractic Management for Veterans with Neck Pain:

A Retrospective Study of Clinical Outcomes

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011 (Oct); 34 (8): 533–538Coulis CM, Lisi AJ.

Chiropractic Management of Postoperative Spine Pain: A Report of 3 Cases

Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2013 (Sep); 12 (3): 168–175Goertz CM, Long CR, Hondras MA, Petri R, Delgado R, Lawrence DJ, et al.

Adding Chiropractic Manipulative Therapy to Standard Medical Care

for Patients with Acute Low Back Pain: Results of a Pragmatic

Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Study

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 (Apr 15); 38 (8): 627–634Khorsan R, Cohen AB, Lisi AJ, et al.

Mixed-Methods Research in a Complex Multisite VA Health Services Study:

Variations in the Implementation and Characteristics

of Chiropractic Services in VA

Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013 (Dec 31); 701280Dougherty P, Karuza J, Dunn A, Savino D, Katz P:

Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Chronic Lower Back Pain in Older Veterans:

A Prospective, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation 2014 (Dec); 5 (4): 154–164Morgan WE, Morgan CP.

Chiropractic care of a patient with neurogenic heterotopic ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament after traumatic brain injury: a case report.

Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2014;13:260-265.Green BN, Browske LK, Rosenthal CM.

Elongated Styloid Processes and Calcified Stylohyoid Ligaments in a Patient with Neck Pain:

Implications for Manual Therapy Practice

Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2014 (Jun); 13 (2): 128–133Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ.

Chiropractic in U.S. Military and Veterans’ Health Care

Military Medicine 2009 (Jun); 174 (6): vi–viiDunn AS.

A chiropractic internship program in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

J Chiropr Educ. 2005;19: 92-96.Dunn AS.

Department of Defense chiropractic internships: a survey of internship participants and nonparticipants.

J Chiropr Educ. 2006;20:115-122.Dunn AS, Towle JJ, McBrearty P, Fleeson SM.

Chiropractic consultation requests in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System: demographic characteristics of the initial 100 patients at the Western New York Medical Center.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:448-454.Green BN, Sims J, Allen R.

Use of Conventional and Alternative Treatment Strategies

for a Case of Low Back Pain in a F/A-18 Aviator

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2006 (Jul 4); 14: 11Dunn AS.

A survey of chiropractic academic affiliations within the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

J Chiropr Educ. 2007;21:138-143.Dunn AS, Passmore SR.

When demand exceeds supply: Allocating chiropractic services at VA medical facilities.

J Chiropr Humanit. 2007;14:22-27.Green BN, Schultz G, Stanley M.

Persistent synchondrosis of a primary sacral ossification center in an adult with low back pain.

Spine J. 2008;8:1037-1041.Dunn, AS and Passmore, SR.

Consultation Request Patterns, Patient Characteristics, and Utilization of

Services within a Veterans Affairs Medical Center Chiropractic Clinic

Military Medicine 2008 (Jun); 173 (6): 599–603Johnson C, Baird R, Dougherty PE, et al.

Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:397-410.Dunn, AS, Passmore, SR, Burke, J, and Chicoine, D.

A Cross-sectional Analysis of Clinical Outcomes Following Chiropractic

Care in Veterans With and Without Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Military Medicine 2009 (Jun); 174 (6): 578–583Passmore, SR and Dunn, AS.

Positive Patient Outcome After Spinal Manipulation in a Case of Cervical Angina

Man Ther. 2009 (Dec); 14 (6): 702–705Lott C.

Integration of chiropractic in the Armed Forces Health Care System.

Military Medicine 1996;161:755-759.Coulter ID.

United States Department of Veterans Affairs Chiropractic Services Pilot Program evaluation study SDR #86-09: a critique.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1993;16:375-383.Dougherty PE, Karuza J, Savino D, Katz P.

Evaluation of a Modified Clinical Prediction Rule For Use With Spinal Manipulative

Therapy in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2014 (Nov 18); 22 (1): 41Enix DE, Flaherty JH, Sudkamp K, Malmstrom TK.

Methodology of a randomized controlled trial of manipulation and physical therapy for chronic low back pain and balance problems in the geriatric population.

Top Integr Health Care. 2011;2(4):1-12.Temple E.

C-force vs. g-force: chiropractic and aviation in America.

Chiropr Hist. 2010;30:47-54.United States Senate.

National Health Program, 1949.

Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare,

United States Senate, Eighty-first Congress, First Session on S. 1106, S. 1456,

S. 1581, and S. 1679, Bills Relative to a National Health Program of 1949.

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1949.United States Congress.

Appointment of Doctors of Chiropractic in the Veterans’ Administration: Hearing,

Eighty-first Congress, Second Session, on H.R. 1512.

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1950.Rehm WS, Fay LE, Keating JC.

Chiropractic goes to Washington: with Dr. Emmett J. Murphy, 1938-1964.

Chiropr Hist. 1994; 14(2):34-42.Murphy EJ.

VFW chiropractic bill in mill.

J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1949;19(2):9-10.Phillips B, Ball C, Sackett D, et al.

Oxford Centre for Evidencebased Medicine levels of evidence (March 2009).

http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-

evidencemarch-2009/

Accessed November 27, 2015.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P.

Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration.

Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:295-309.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344-349.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews

and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement

PLoS Medicine 2009 (Jul 21); 6 (7): e1000100Eisenberg D, Kessler R, Foster C, Norlock F, Calkins D, Delbanco T.

Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs, and Patterns of Use

New England Journal of Medicine 1993 (Jan 28); 328 (4): 246–252Tindle H, Davis R, Phillips R, Eisenberg D.

Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997-2002.

Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11(1):42-49.Peregoy JA, Clarke TC, Jones LI, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL.

Regional variation in use of complementary health approaches by U.S. adults.

NCHS Data Brief. 2014;(146):1-8.Meeker, W., & Haldeman, S. (2002).

Chiropractic: A Profession at the Crossroads of Mainstream and Alternative Medicine

Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (Feb 5); 136 (3): 216–227Smith TC, Ryan MA, Smith B, et al.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among US Navy and Marine Corps Personnel

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007 (May 16); 7: 16Jacobson IG, White MR, Smith TC, et al.

Self-reported health symptoms and conditions among complementary and alternative medicine users in a large military cohort.

Ann Epidemiol. 2009; 19:613-622.Goertz C, Marriott BP, Finch MD, et al.

Military Report More Complementary and

Alternative Medicine Use Than Civilians

J Altern Complement Med. 2013 (Jun); 19 (6): 509–517Davis MT, Mulvaney-Day N, Larson MJ, Hoover R, Mauch D.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Among Veterans and

Military Personnel: A Synthesis of Population Surveys

Medical Care 2014 (Dec); 52 (12 Suppl 5): S83–90Ezeji-Okoye SC, Kotar TM, Smeeding SJ, Durfee JM.

State of care: complementary and alternative medicine in Veterans Health Administration—2011 survey results.

Fed Pract. 2013;30(11): 14-19.Fletcher CE, Mitchinson AR, Trumble EL, Hinshaw DB, Dusek JA.

Perceptions of providers and administrators in the Veterans Health Administration regarding complementary and alternative medicine.

Med Care. 2014;52(12 suppl 5):S91-S96.Reinhard MJ, Nassif TH, Bloeser K, et al.

CAM utilization among OEF/OIF veterans: findings from the National Health Study for a New Generation of US Veterans.

Med Care. 2014;52(12 suppl 5): S45-S49.Baldwin CM, Long K, Kroesen K, Brooks AJ, Bell IR.

A profile of military veterans in the southwestern United States who use complementary and alternative medicine: implications for integrated care.

Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1697-1704.McEachrane-Gross FP, Liebschutz JM, Berlowitz D.

Use of Selected Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Treatments in Veterans with

Cancer or Chronic Pain: A Cross-sectional Survey

BMC Complement Altern Med 2006 (Oct 6); 6: 34Denneson LM, Corson K, Dobscha SK.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among

Veterans With Chronic Noncancer Pain

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011; 48 (9): 1119–1128George S, Jackson JL, Passamonti M.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine in a Military Primary Care Clinic: A 5-year Cohort Study

Military Medicine 2011 (Jun); 176 (6): 685–688Dorflinger L, Moore B, Goulet J, et al.

A partnered approach to opioid management, guideline concordant care and the stepped care model of pain management.

J Gen Intern Med. 2014; 29(suppl 4):870-876.Kent JB, Oh RC.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Military Family Medicine Patients in Hawaii

Military Medicine 2010 (Jul); 175 (7): 534–538Baldwin CM, Kroesen K, Trochim WM, Bell IR.

Complementary and conventional medicine: a concept map.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4:2.Campbell DG, Turner AP, Williams RM, et al.

Complementary and alternative medicine use in veterans with multiple sclerosis: prevalence and demographic associations.

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43:99-110.Ceylan S, Hamzaoglu O, Komurcu S, Beyan C, Yalcin A.

Survey of the use of complementary and alternative medicine among Turkish cancer patients.

Complement Ther Med. 2002;10(2): 94-99.Cherniack EP, Pan CX.

Alternative and complementary medicine for elderly veterans: why and how they use it.

Altern Complement Ther. 2002;8:291-294.Cherniack EP, Senzel RS, Pan CX.

Correlates of use of alternative medicine by the elderly in an urban population.

J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:277-280.Cretin S, Farley DO, Dolter KJ, Nicholas W.

Evaluating an integrated approach to clinical quality improvement: clinical guidelines, quality measurement, and supportive system design.

Med Care. 2001;39(8 suppl 2):II70-II84.Davis GE, Bryson CL, Yueh B, McDonell MB, Micek MA, Fihn SD.

Treatment delay associated with alternative medicine use among veterans with head and neck cancer.

Head Neck. 2006; 28:926-931.Drivdahl CE, Miser WF.

The use of alternative health care by a family practice population.

J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11: 193-199.Druss BG, Rohrbaugh R, Kosten T, Hoff R, Rosenheck RA.

Use of alternative medicine in major depression.

Psychiatr Serv. 1998; 49:1397.Garback LM, Lancaster KJ, Pin˜ero DJ, Bloom ED, Weinshel EH.

Use of herbal complementary alternative medicine in a veteran outpatient population.

Top Clin Nutr. 2003;18:170-176.Harris BS.

Use of Alternative Therapies by Active duty Air Force Personnel (master’s thesis).

Bethesda, MD: Graduate School of Nursing,

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; 1996.Isikhan V, Komurcu S, Ozet A, et al.

The status of alternative treatment in cancer patients in Turkey.

Cancer Nurs. 2005;28: 355-362.Kramer BJ, Jouldjian S, Washington DL, Harker JO, Saliba D, Yano EM.

Health care for American Indian and Alaska native women.

Womens Health Issues. 2009;19:135-143.Ketz AK.

Pain management in the traumatic amputee.

Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;20:51-57.Kroesen K, Baldwin CM, Brooks AJ, Bell IR.

US military veterans’ perceptions of the conventional medical care system and their use of complementary and alternative medicine.

Fam Pract. 2002;19:57-64.Makela JP.

Arnold-Chiari malformation type I in military conscripts: symptoms and effects on service fitness.

Military Medicine 2006;171:174-176.Oakes MJ, Sherwood DL.

An isolated long thoracic nerve injury in a Navy Airman.

Military Medicine 2004;169:713-715.Strader DB, Bacon BR, Lindsay KL, et al.

Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with liver disease.

Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2391-2397.Smith TC, Smith B, Ryan MA.

Prospective investigation of complementary and alternative medicine use and subsequent hospitalizations.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:19.Suarez T, Reese FL.

Coping, psychological adjustment, and complementary and alternative medicine use in persons living with HIV and AIDS.

Psychol Health. 2000;15:635-649.Tan G, Alvarez JA, Jensen MP.

Complementary and alternative medicine approaches to pain management.

J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:1419-1431.Duncan AD, Liechty JM, Miller C, Chinoy G, Ricciardi R.

Employee use and perceived benefit of a complementary and alternative medicine wellness clinic at a major military hospital: evaluation of a pilot program.

J Altern Complement Med. 2011; 17:809-815.Elwy AR, Johnston JM, Bormann JE, Hull A, Taylor SL.

A systematic scoping review of complementary and alternative medicine mind and body practices to improve the health of veterans and military personnel.

ed Care. 2014;52(12 suppl 5): S70-S82.Gilbey A.

Subject expectancy effect or the effect of chiropractic manipulative therapy?

Focus Altern Complement Ther. 2013;18: 213-214.Holliday SB, Hull A, Lockwood C, Eickhoff C, Sullivan P, Reinhard M.

Physical health, mental health, and utilization of complementary and alternative medicine services among Gulf War veterans.

Med Care. 2014;52(12 suppl 5):S39-S44.Lisi AJ, Burgo-Black AL, Kawecki T, Brandt CA, Goulet JL.

Use of Department of Veterans Affairs administrative data to identify veterans with acute low back pain: a pilot study.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39:1151-1156.Netto K, Hampson G, Oppermann B, Carstairs G, Aisbett B.

Management of Neck Pain in Royal Australian Air Force Fast Jet Aircrew

Military Medicine 2011 (Jan); 176 (1): 106–109Ross EM, Darracq MA.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Practices in Military Personnel

and Families Presenting to a Military Emergency Department

Military Medicine 2015 (Mar); 180 (3): 350–354Ward J, Coats J, Pourmoghaddam A.

Spine Buddy1 supportive pad impact on single-leg static balance and a jogging gait of individuals wearing a military backpack.

J Hum Kinet. 2014;44: 53-66.Ward J, Coats J, Devers A, Murphy B.

Supportive pad impact on upper extremity blood flow while wearing a military backpack.

Top Integr Health Care. 2014;5(2):1-12.McPherson F, Schwenka MA.

Use of complementary and alternative therapies among active duty soldiers, military retirees, and family members at a military hospital.

Military Medicine 2004;169: 354-357.Micek MA, Bradley KA, Braddock CH 3rd, Maynard C, McDonell M, Fihn SD.

Complementary and alternative medicine use among Veterans Affairs outpatients.

J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:190-193.Rix GD, Rothman EH, Robinson AW.

Idiopathic neuralgic amyotrophy: an illustrative case report.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:52-59.Roberts DM.

Alternative medicine: the attitude of the Army Medical Services.

J R Army Med Corps. 1985;131:159-163.Chapman C, Bakkum BW.

Chiropractic Management of a US Army Veteran with Low Back Pain

and Piriformis Syndrome Complicated by an Anatomical Anomaly

of the Piriformis Muscle: A Case Study

J Chiropractic Medicine 2012 (Mar); 11 (1): 24–29Fedorchuk C, Campbell C.

Improvement in a soldier with urinary urgency and low back pain undergoing chiropractic care: a case study and selective review of the literature.

J Vertebral Subluxation Res. 2010;(April 28):1-5.Heiner JD.

Cervical epidural hematoma after chiropractic spinal manipulation.

Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:1023.e1021-1022.Lidder S, Lang KJ, Masterson S, Blagg S.

Acute spinal epidural haematoma causing cord compression after chiropractic neck manipulation: an under-recognised serious hazard?

J R Army Med Corps. 2010;156:255-257.Roberts JA, Wolfe TM.

Chiropractic management of a veteran with lower back pain associated with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hypertrophy and degenerative disk disease.

Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 2012;11:293-299.Yu H, Hou S, Wu W, He X.

Upper cervical manipulation combined with mobilization for the treatment of atlantoaxial osteoarthritis: a report of 10 cases.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011; 34:131-137.Reife MD, Coulis CM.

Peroneal neuropathy misdiagnosed as L5 radiculopathy: a case report.

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2013;21(1): 12.Beliakin SA, Burlak AM.

Organizational and methodological approaches to the medical rehabilitation of the wounded from the consequences of combat trauma in the upper limb in rehabilitation center [in Russian].

Voen Med Zh. 2012;333(9):12-16.

Return to PATIENT SATISFACTION

Return to INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 6-19-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |