Integration of Chiropractic Services into

a Multidisciplinary Safety-Net ClinicThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Topics Integr Health Care. 2010 (Sep 1); 1: 1: 1005 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Mark T. Pfefer, RN, MS, DC; Richard Strunk DC, MS; Cheryl Hawk, DC, PhD, CHES; Michael Ramcharan, DC, MPH, MUA-C; Elizabeth Pa Xiong; Diane Hill, BSN, MSN, EdD, ARNP; Lauren Davis

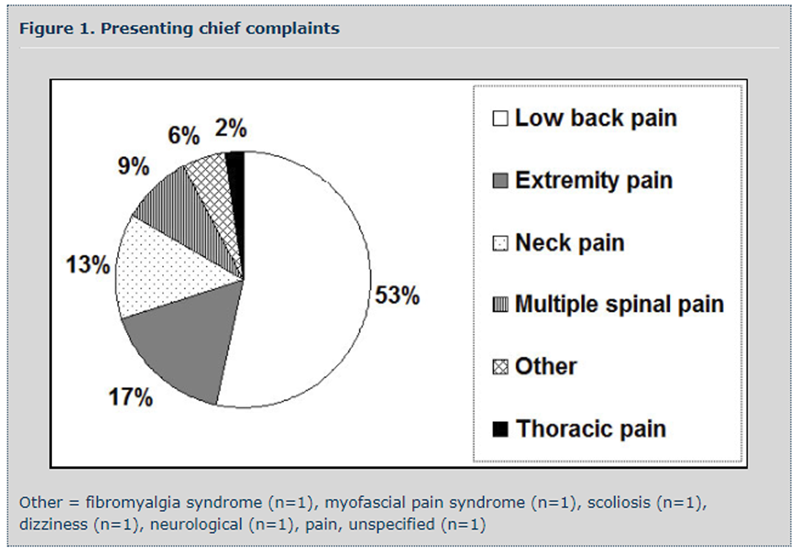

Nearly 46 million Americans are uninsured. Health care safety-net providers are those that have a mission to offer health care to all patients, regardless of their ability to pay, and typically have a substantial number of patients who are uninsured. This paper describes the establishment of a chiropractic clinic within a free, safety-net health clinic operating in a “medical pluralism” model. In this particular collaborative arrangement, chiropractic was categorized as a specialty service, so patients were referred by the clinic’s primary care physician or nurse practitioner. Ninety one new patients were examined and treated during the first 9 months of integrating chiropractic services into the clinic. Musculoskeletal complaints, particularly low back pain (53%), extremity pain (17%) and neck pain (13%) represented the majority of the type of problems that patients presented for care. Fifty percent of the chiropractic patients were unemployed, and 77% presented with an unhealthy body mass index; 33% were current tobacco users. The first 9 months of integrating chiropractic services was viewed as successful due to consistently full patient appointment times and frequent referrals from other health care providers within the free clinic. Our challenges were almost exclusively logistical in nature. Staffing the chiropractic service was perhaps the primary challenge.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Background of the Health Partnership Clinic

Nearly 46 million Americans are uninsured. More than 8 out of 10 uninsured persons are in working families that cannot afford health insurance, and many are not eligible for public programs. [1] Health care safety-net providers are those that have a mission to offer health care to all patients, regardless of their ability to pay, and typically have a substantial number of patients who are uninsured.

Created in 1992, the Health Partnership Clinic of Johnson County, Kansas (HPCJC), provides free medical and dental care to low income, uninsured Johnson county residents at two sites. Through partnerships with organizations in the area and over 80 volunteer health professionals and clerical workers, HPCJC has become the largest safety-net clinic in the county. Of the 55,000 uninsured in Johnson County, 16,500 qualify for care at HPCJC. In order to qualify, patients must meet the following requirements:1) be a resident of Johnson County, Kansas;

2) be uninsured and not qualify for Medicaid, Medicare, Healthwave or other government healthcare assistance;

3) have a household income at 200% of the federal poverty level or below. For a family of four, this would be an annual household income of $44,100.The clinic’s goal is to serve as a medical home for its patients, and over 80% of clinic patients have one or more chronic diseases requiring ongoing management. The clinic had approximately 10,000 patient visits in 2009, with a mean number of visits per patient of 3.2.

Services provided include primary acute and specialty care, chronic disease management, clinical preventive services and dental care. Prior to the integration of chiropractic into the facility, specialty care included gynecology, urology, cardiology, rheumatology, orthopedics, dermatology, pulmonology, allergy/asthma, internal medicine and otolaryngology (ENT). Some laboratory tests and procedures are performed on site. The clinic partners with the five major hospitals of Johnson County, which provide in-kind radiology and laboratory services. No on-site care for patients with mechanical musculoskeletal pain was available. Patients had to be referred to physical therapists associated with the clinic’s specialty care network, or to local chiropractors who were not associated with the network and who provided fee-for-service care only.

The 6,000 square foot clinic has five examination rooms, one procedure and examination room, one patient education room, and an area dedicated to lab draws. The clinic uses a web based, integrated practice management system and an electronic medical records system by Medkind Electronic Medical Record/Electronic Health record (EMR/HER) system. The EMR collects data on patient demographics, diagnoses, services delivered, prescription and nonprescription medications, referrals for other medical services or specialty care and other information pertinent to tracking patient care. All health care providers have computer access to this electronic system in each of the examination rooms.

Due to the diversity of the clinic’s patient population, a language translation service is available by phone in all rooms and areas where patients are examined and treated.

Methods

It has been recommended that the chiropractic profession develop methods to increase integration into mainstream health care. [2] According to the Council on Chiropractic Education (CCE), the national accrediting body for chiropractic, an accredited doctor of chiropractic (DC) program prepares its graduates to practice direct access health care as a primary contact portal-of-entry provider for patients of all ages. [3] In fulfilling this role there is a need for DC programs to provide care to diverse population groups, including underserved and uninsured patients. Chiropractic care is increasingly being included as part of integrated care settings, including facilities serving the military, [4] Veteran’s Administration, [5] primary care, [6–8] and underserved populations. [9] This paper describes the establishment and integration of a chiropractic clinic within a free, safety-net health clinic operating in a large suburban area in the Midwest.

Integration of Chiropractic Services into the HPCJC

The integration process at HPCJC followed what has been called the “medical pluralism” model. [10, 11] In this model, mainstream medical practitioners and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) providers work in proximity, autonomously, but with a mutual attitude of cooperation and tolerance. [11] Thus, patient care options are increased, while not requiring practitioners to modify their usual and customary approaches. For a facility like HPCJC, which already places high demands on the time of its volunteer providers, this model appeared most feasible.

In 2009, preliminary discussions between Cleveland Chiropractic College research faculty and the administration of HPCJC began concerning the possibility of integrating chiropractic services into the clinic. The clinic directors felt it would be beneficial to patients to offer conservative care for musculoskeletal conditions, which were prevalent in their patient population. The research center at the college made a commitment to provide clinical services to patients while collecting observational data. The study was approved by the college’s Institutional Review Board prior to the provision of any services.

Referral Mechanism

Because the clinic staff assumed that many, if not most, of their patient population would be unfamiliar with chiropractic, patients were first seen by the chiropractic clinicians after referral by other clinic providers. Thus, for this particular collaborative arrangement, chiropractic was categorized as a specialty service. At the HPCJC, patients are typically triaged by the nurses or medical assistants on the first encounter and initially seen by a primary care physician (PCP) or the clinic’s nurse practitioner (NP). After their initial assessment of the patient, they determine whether the patient requires a referral to a specialist for further evaluation. The PCP or NP encouraged patients with musculoskeletal conditions to see the chiropractor, for treatment of those conditions. The patients are typically co-managed with multiple practitioners who have full access to all medical records from all providers (EMR/EHR).

Physical Facilities

The chiropractic treatment room, which was originally an administrative office, is a typical treatment room equipped with a Leander motorized flexion distraction table, a hydroculator, a therapeutic ultrasound machine and a computer to access the electronic medical records system. The chiropractic college that partnered with HPCJC provided all equipment used for chiropractic services. The chiropractors providing services were all clinical and/or research faculty of the college, providing care as part of the research portion of their responsibilities.

Chiropractic Services Provided

All chiropractic care, including examinations and assessments, was delivered by four licensed doctors of chiropractic with a practice experience range of 8 to 26 years. New chiropractic patients were assessed with a detailed history and a focused orthopedic/neurological and functional examination. Vitals including weight, height, temperature, and blood pressure were performed by a member of the nursing staff prior to seeing the chiropractic clinician. Plain film radiographs or laboratory tests were ordered when necessary. New patients were treated the same day of the initial evaluation if no further tests were warranted. First visit evaluations and treatments took 45–60 minutes depending on the complexity of the patient’s chief complaint and health history. Standardized outcome measures included the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for pain and the Roland Morris low back questionnaire.

The chiropractic care delivered reflected common chiropractic practice. As a result, the care incorporated various spinal manipulation (SM) techniques such as diversified, instrument-assisted, drop table, motorized flexion distraction, and assorted soft tissue therapies such as Graston, myofascial release, and Post Isometric Relaxation. Adjunctive therapeutic modalities such as ultrasound and moist heat therapy were also performed and low-tech strengthening and stretching exercises were prescribed for home self care. The care was tailored to each patient and was performed by experienced, licensed chiropractic clinicians. Each visit took approximately 15–20 minutes. In addition to the chiropractic care, health promotion counseling by a DC who was also a Certified Health Education Specialist was also available to chiropractic patients who smoked and/or who were overweight or obese. At the peak of DC coverage, chiropractic services were delivered 16 hours per week covering three different days of the week.

Results

Chiropractic Patient Population

Figure 1

Table 1 Part A

Table 1 Part B Ninety one new patients were examined and treated during the first 9 months of integrating chiropractic services into HPCJC. Musculoskeletal complaints, particularly low back pain (53%), extremity pain (17%) and neck pain (13%) represented the majority of the type of problems that patients presented for care (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes their characteristics. Fifty percent of the chiropractic patients were unemployed. The majority (77%) were either overweight or obese, with 41% being obese. One third (33%) used tobacco. The most commonly used medications by the patients seeking chiropractic care were antihypertensives (43%), analgesics (41%) and antidepressants (41%). Chiropractic patients were seen an average of 7 times within the 9 months represented by these data.

Outcomes of the Collaborative Arrangement

The first 9 months of integrating chiropractic services was viewed as successful due to consistently full patient appointment times and frequent referrals from other health care providers within the HPCJC. Appointment times for chiropractic care were consistently full the same day of care and for several weeks in advance. Many patients were referred for chiropractic services from various orthopedic and internal medicine providers and from a nurse practitioner during the first 9 months. In addition, frequent referrals were made by DCs to various medical physicians and other providers such as orthopedic surgeons, internists, and physical therapists. Due to scheduling difficulties and lack of additional space, health promotion counseling services by our DC/CHES were discontinued.

The patient-oriented outcome measures originally planned (Roland Morris Questionnaire and the NRS) have yet to be implemented due to logistic issues with the EHR, as well as decreased DC coverage and the scheduling conflict between scheduling new patients and scheduling regular follow up visits.

Challenges and Solutions

Our challenges were almost exclusively logistical in nature. [12] Staffing the chiropractic service was perhaps the primary challenge. All health professionals at HPCJC are unpaid volunteers. Because we were unable to identify local DCs who were able to volunteer their time, research faculty of the nearby chiropractic college served in this capacity. A benefit of this solution is that we were able to develop the HPCJC chiropractic service into a learning experience for the college’s interns, who were allowed to observe and assist in patient care. However, even with the research clinicians available, the demands could not be met and waiting lists developed. After the initial 9 months of the project, due to budget constraints, we were required to cut back the hours of operation of the chiropractic service even further, and at this time are only able to provide 4 hours of chiropractic care per week. Another challenge was that, although we had a DC with training (Certified Health Education Specialist) and experience in health promotion counseling available for patients, due to time and space constraints at the clinic, it became impossible to provide this much-needed service.

Although the EHR system worked well for record-keeping in general, there were some challenges related to integrating the chiropractic patient forms into it. The outcome assessments we originally intended to use (NRS for pain and the RMQ) were inadvertently omitted from the EHR, which resulted in these data not being collected. We are now addressing this issue by using hard copies, administered by the chiropractor to each patient at each visit.

Discussion

The patient population at HPCJC is quite distinct from the general population of the area, and from the U.S. population in general, because it represents the uninsured, low-income residents of the area. Reflecting the HPCJC patient population, 50% of chiropractic patients were unemployed and none had health insurance, which of course was a requirement for eligibility to use the clinic. One third (33%) did not speak English. The most striking health-related characteristic of were that 33% were smokers, compared to 20% of the U.S. population in general. [13] Furthermore, 77% were overweight/obese, with 41% obese; these are similar, although higher proportions compared to those of the general U.S. population. [14, 15] With respect to medication use, 43% were taking antihypertension medications, 41% were taking antidepressants and 41% analgesics. All these characteristics can be linked to the stress of being unemployed or underemployed and uninsured. From these observations, it is clear that resources for health promotion and prevention should be a priority in future endeavors.

Safety-net clinics like HPCJC are an essential feature of our current health care system; without such clinics, a significant proportion of the population would be completely without recourse when they become ill, and have no possibility of being provided with preventive care of any type. Chiropractic can offer an effective approach to many common conditions, particularly musculoskeletal pain. [16] Because pain, in general, is the most common reason for people to seek medical care, [17] the integration of chiropractic into safety-net clinics can therefore greatly increase these clinics’ ability to meet the increasing needs of their target population. However, chiropractic is not routinely considered a part of the primary care team, [18] even though painful musculoskeletal conditions are among the most common complaints in primary care practice, [19] and thus may not even be considered when safety-net clinics providing primary care are established. Consequently, we feel that demonstrating the feasibility of integrating chiropractic into such a clinic is an important contribution to the development of effective methods for serving underserved populations in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katherine Smith, DC, for her clinical expertise in examining and providing chiropractic care for patients at the HPCJC. The authors also thank Amanda Lowe, President/CEO HPCJC, for her support and continuing commitment to the integration of chiropractic care into the HPCJC. The authors thank Performance Health–Health and Wellness products (Biofreeze and Thera-Band), the Pressure Positive Company (deep muscle treatment tools), and Straight Arrow Products (Medic Ice, Foot Miracle, and Urea Care) for generously donating equipment and supplies.

References:

DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC.

Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2008.

In: Bureau USC, ed:

U.S Government Printing Office; 2009:20.The Institute for Alternative Futures

The Future of Chiropractic Revisited: 2005 to 2015

Alexandria, VA: (2005)Council on Chiropractic Education.

Standards for Doctor of Chiropractic Programs and Requirements for Institutional Status.

Greeley, CO: Council on Chiropractic Education, 2007Goldberg C.K., Green B., Moore J.

Integrated Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation Care at a Comprehensive

Combat and Complex Casualty Care Program

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 781–791Dunn AS, Green BN, Gilford S.

An Analysis of the Integration of Chiropractic Services Within

the United States Military and Veterans' Health Care Systems

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 749–757Garner MJ, Aker P, Balon J, Birmingham M, Moher D, Keenan D, et al.

Chiropractic Care of Musculoskeletal Disorders in a Unique Population

Within Canadian Community Health Centers

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Mar); 30 (3): 165–170Garner MJ, Birmingham M, Aker P, Moher D, Balon J, Keenan D, Manga P.

Developing Integrative Primary Healthcare Delivery:

Adding a Chiropractor to the Team

Explore (NY). 2008 (Jan); 4 (1): 18–24Richard L. Sarnat, MD, James Winterstein, DC, Jerrilyn A. Cambron, DC, PhD

Clinical Utilization and Cost Outcomes from an Integrative Medicine

Independent Physician Association: An Additional 3-year Update

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (May); 30 (4): 263–269Kopansky-Giles D, Vernon H, Steiman I, Tibbles A, Decina P, Goldin J, et al.

Collaborative Community-Based Teaching Clinics at the Canadian Memorial

Chiropractic College: Addressing the Needs of Local Poor Communities

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Oct); 30 (8): 558–565Stevens L, Duarte H, Park J.

Promising implications for integrative medicine for back pain:

a profile of a Korean hospital.

J Altern Complement Med. Jun 2007;13(5):481-484.Kaptchuk TJ, Miller FG.

Viewpoint: what is the best and most ethical model for the relationship between

mainstream and alternative medicine: opposition, integration, or pluralism?

Acad Med. Mar 2005;80(3):286-290.Verhoef MJ, Mulkins A, Kania A, Findlay-Reece B, Mior S.

Identifying the barriers to conducting outcomes research in integrative health

care clinic settings--a qualitative study.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:14.Davis S.

State-specific prevalence and trends in adult cigarette smoking-United States, 1998-2007.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly. 2009;58:221-226.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR.

Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008.

JAMA. Jan 20;303(3):235-241.Ogden C, Carroll, MD.

Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults:

United States, trends 1976-1980 through 2007-2008.

Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010.Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leiniger B, Triano J.

Effectiveness of Manual Therapies: The UK Evidence Report

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Feb 25); 18 (1): 3Brawer PA.

Pain in Primary Care Settings.

New York: Springer, 2008.Gaumer G, Gemmen E.

Chiropractic users and nonusers: differences in use, attitudes, and willingness

to use nonmedical doctors for primary care.

J Manupulative Physiol Ther 2006;29(7):529-539.Ahles TA, Wasson JH, Seville JL, et al.

A controlled trial of methods for managing pain in primary care patients with or

without co-occurring psychosocial problems.

Ann Fam Med. Jul-Aug 2006;4(4):341-350.

Return to INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE

Since 4-12-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |