Management of Back Pain-related Disorders in a Community

With Limited Access to Health Care Services: A

Description of Integration of Chiropractors

as Service ProvidersThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2017 (Nov); 40 (9): 635–642 ~ FULL TEXT

Peter C. Emary, DC, MSc, Amy L. Brown, DC, Douglas F. Cameron, DC,

Alexander F. Pessoa, DC, ICSSP, Jennifer E. Bolton, PhD, MA Ed

Postgraduate Studies and Research,

Anglo-European College of Chiropractic,

Bournemouth, England, United Kingdom.

FROM: Gallup-Palmer Annual Report 2016Objective: The purpose of this study was to evaluate a chiropractic service for back pain patients integrated within a publicly funded, multidisciplinary, primary care community health center in Cambridge, Ontario, Canada.

Methods: Patients consulting for back pain of any duration were referred by their medical doctor or nurse practitioner for chiropractic treatment at the community health center. Patients completed questionnaires at baseline and at discharge from the service. Data were collected prospectively on consecutive patients between January 2014 and January 2016.

Results: Questionnaire data were obtained from 93 patients. The mean age of the sample was 49.0 ± 16.27 years, and 66% were unemployed. More than three-quarters (77%) had had their back pain for more than a month, and 68% described it as constant. According to the Bournemouth Questionnaire, Bothersomeness, and global improvement scales, a majority (63%, 74%, and 93%, respectively) reported improvement at discharge, and most (82%) reported a significant reduction in pain medication. More than three-quarters (77%) did not visit their primary care provider while under chiropractic care, and almost all (93%) were satisfied with the service. According to the EuroQol 5 Domain questionnaire, more than one-third of patients (39%) also reported improvement in their general health state at discharge.

Conclusion: Implementation of an integrated chiropractic service was associated with high levels of improvement and patient satisfaction in a sample of patients of low socioeconomic status with subacute and chronic back pain.

Keywords: Back Pain; Chiropractic; Community Health Centers; Health Services Research.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Back pain is a prevalent health problem in the general population and places a tremendous socioeconomic burden on society. Globally, an average of nearly 40% of individuals will experience low back pain at some point in their life, and approximately 1 in 5 are afflicted at any given time. [1] Low back pain is the leading cause of years lived with disability [2] and is among the most common reasons for visiting a primary care physician. [3, 4] As the world’s population ages, the number of people with back pain and other musculoskeletal disorders is expected to rise. [1, 4] Moreover, these conditions are costly. In Canada, for example, musculoskeletal conditions rank third behind only cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric disorders with respect to medical expenditures (ie, physician services, pharmaceuticals, and hospital care). [5] The societal burden of back pain in terms of economic costs and health resource utilization is also greater among patients with multiple comorbidities, including those of low socioeconomic status. [6–9]

There is evidence to support chiropractic care, including spinal manipulation, as an effective and relatively cost-effective intervention in managing patients with back pain and other musculoskeletal conditions, [10–15] and patients typically report high levels of satisfaction with treatment. [14–16] Despite this, access to chiropractic services is not routinely available through publicly funded health care systems in most countries around the world. As such, patients must either use insurance benefits (if any) or pay out-of-pocket for chiropractic treatment. This presents a significant barrier for lower-income groups including the unemployed. [17]

In Ontario, Canada, chiropractic care is not publicly funded. However, as low back pain is such a common problem, the government is looking at different ways to address this. For instance, the provincial government, under its Low Back Pain Strategy, recently announced the provision of limited, one-time pilot funding for the integration of allied health care providers, including chiropractors, within a select number of interprofessional primary care team settings. [18] Notably, chiropractors were also added to the list of health professionals eligible to be employed by these teams. [19] The objective of these initiatives is to improve the management of low back pain in primary care in Ontario, as provided in nurse practitioner-led clinics, family health teams, aboriginal health access centers, and community health centers. [18, 19]

Community health centers (CHCs) are nonprofit, publicly funded organizations that provide primary health care traditionally from a team of medical doctors, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, dieticians, social workers, and community health workers. [20] The focus of a CHC is on health promotion, illness prevention, and community development. Its services are provided to priority populations who experience barriers to access (eg, language, culture, physical disabilities, homelessness, and poverty), as well as isolated seniors, at-risk children and youths, and individuals with mental health or addiction issues. Musculoskeletal disorders, including chronic back pain, are prevalent among these patient populations, [17, 21] yet many have traditionally faced barriers to accessing chiropractic care.

In Cambridge, Ontario, Canada, a self-directed group of chiropractors from the Waterloo Regional Chiropractic Society recently established an agreement with the Langs organization22 to provide a partially subsidized chiropractic service within their CHC. The agreement was reached after several face-to-face discussions between the chiropractors and the executive staff of Langs, with the goal of creating access to chiropractic care for back pain-related disorders in a community with limited access to health care services. From its inception in January 2014, this program has been completely integrated, and all participating chiropractors to date have had full access to the Center’s electronic medical records system. Yet, despite being a novel initiative for Langs, this is not the first program of its kind in Canada. Successful integration of chiropractic has previously been described within 3 other CHCs in the provinces of Ontario [21, 23, 24] and Manitoba, Canada. [25] However, studies evaluating or demonstrating the value of these services within other Canadian CHC settings are scarce. The aim of this study was to describe a service provided by chiropractors for back pain patients integrated within a multidisciplinary primary care CHC setting using a health services research design and focused on patient-reported outcomes and satisfaction with treatment.

Methods

Service Design

This was a service evaluation [26] of a new back pain service provided by chiropractors integrated into a primary care CHC setting. This initiative provided access to chiropractic care on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 12 to 2 PM (for a total of 4 hours per week) at the Langs CHC. The service was provided on a rotating basis by 4 chiropractors (P.C.E., A.L.B., D.F.C., and A.F.P.). Eligible patients were those at Langs who were seen by their primary care medical doctor or nurse practitioner for back pain (of any duration), were unable to privately pay for chiropractic care, and were suitable for manual therapy (ie, absence of “red flags”). [27] The service was pragmatic in that each patient was assessed and treated as would occur in usual chiropractic practice. Treatment sessions were evidence based [27] and included any or all of the following: high-velocity, low-amplitude spinal manipulative therapy (applied to the lumbar and/or thoracic spine); soft-tissue massage/trigger point therapy; education and reassurance (eg, pain management, ergonomic, and activities of daily living recommendations); and home advice (eg, icing, spinal stretching, and core muscle strengthening exercises). Consistent with current clinical practice guidelines, [27] patients were discharged after 3 months or a maximum of 12 visits, although some continued with treatment after discharge from the service evaluation to manage further episodes of exacerbation/flare-up. Patients discharged prior to this were those not responding to care or those who had reached a clinical plateau in their recovery (ie, maximum therapeutic benefit). [27]

Data Collection

Similar to methodology employed by Gurden et al, [28] this service was evaluated using patient-reported outcome measures, and data were collected prospectively throughout the first 2 years of the program between January 2014 and January 2016. On entry to the service (ie, baseline), patients were asked to complete a comprehensive questionnaire including sociodemographic data and clinical characteristics of their back pain complaint. Outcome measures included the Bournemouth Questionnaire (BQ), a validated outcome measure for back pain, [29] designed for use in the routine practice setting; the Bothersomeness questionnaire [30]; and the EuroQol 5 Domain (EQ-5D) measure of general health status. [31] Patients then completed a second questionnaire at discharge from the service. This included the BQ, the Bothersomeness questionnaire, and EQ-5D, as well as a 7–point global improvement scale (ie, completely better, much better, slightly better, no change, slightly worse, worse, and much worse), a 5–point patient satisfaction with treatment scale (ie, very satisfied, satisfied, unsure, dissatisfied, and very dissatisfied), and details of medication usage, other health care utilization, and work status. To reduce bias, all pre- and posttreatment questionnaires were administered independent of the treating chiropractors, via the reception staff at the front desk of the CHC.

Data Analysis

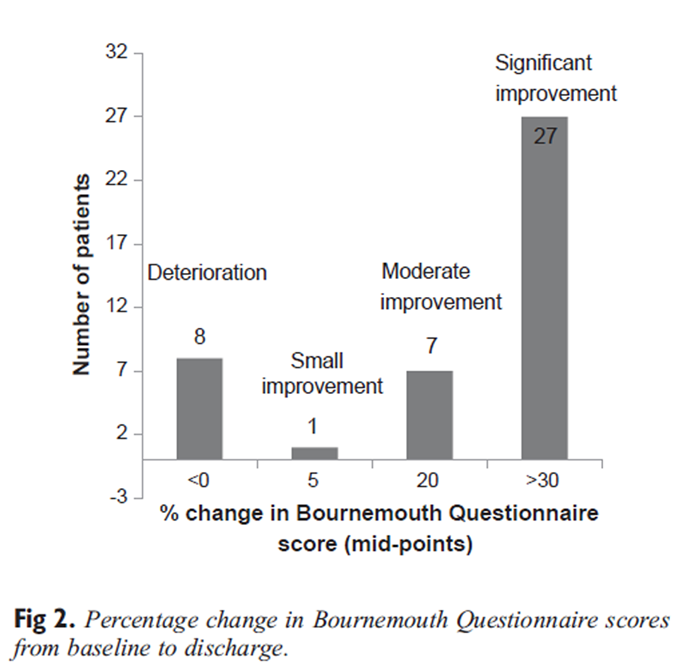

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristic data from the questionnaires. Percentage changes in BQ scores were calculated and categorized on an arbitrary scale as “deterioration” (≤0), as “small improvement” (1–10), as “moderate improvement” (11–30), and as “significant improvement” (>30). This was based on the assumption that a >30% change score is interpreted as a clinically significant change. [32] Bothersome change scores were categorized as “deterioration” (<0), as “no change” (=0), and as “improvement” (>0). Finally, changes in EQ-5D scores were analyzed according to the method outlined by Devlin et al [33] and Gutacker et al. [34] Data analysis was carried out using SPSS, Version 20 (IBM, Armonk, New York).

Ethical Considerations

The Anglo-European College of Chiropractic Policy and Procedures on Research Ethics and the Research Ethics Board Secretariat for Health Canada considered this study exempt from review. All patients were informed in writing that the information given in the questionnaires would be used anonymously.

Results

Sample Characteristics at Baseline

Table 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

+

Figure 5 In total, 93 consecutive patients reporting low back pain were included in this service evaluation. Age ranged from 18 to 84 years (mean: 49.0 ± 16.27 years), with just more than half (55%) of the sample being female and a third (34%) in paid employment. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample at baseline.

A substantive proportion (77%) of patients reported musculoskeletal pain in areas additional to the back. Of these, the most common area was pain radiating into the leg(s) (78%), followed by neck pain (46%), shoulder pain (32%), and headache (29%). In terms of chronicity of their back pain, most (77%) had had the same or similar condition in the past. Again, in most cases (77%), the present episode had lasted more than a month, and the majority of patients (68%) described their back pain as constant. These findings point to a mostly chronic back pain population with widespread pain, but importantly with the expectation at the outset that they would improve with treatment.

The problems patients reported at baseline, as assessed with the EQ-5D, are illustrated in Figure 1. Most patients experienced problems with their mobility, usual activities (work, study, housework, family, or leisure activities), anxiety/depression, and, of course, pain. Interestingly, problems with self-care (washing and dressing) were not highly reported by patients. It should be noted that the EQ-5D is a generic health state questionnaire,31 and patients are not directed specifically to their back pain when completing it.

Health Outcomes and Patient Satisfaction at Discharge

Of the 93 patients included in this study, 44 (47%) completed questionnaires at discharge. The mean time between completing the pretreatment and discharge questionnaires was 10.2 ± 8.32 weeks, with a wide range from 1 to 47 weeks. Most patients (77%) had not sought help from any other practitioner for their back pain during this time, most (82%) either were not taking any medication or had managed to significantly reduce their medication usage for their pain, and almost all (93%) were either very satisfied or satisfied with the treatment they had received from this service.Bournemouth Questionnaire Figure 2 illustrates the percentage change in total BQ score from baseline to discharge. Almost two-thirds of patients (63%) were categorized using this score as significantly improved.

Bothersomeness Scale As assessed with change scores on the Bothersomeness scale (Figure 3), the majority of patients (74%) reported improvement, with no patients reporting that the bothersomeness of their back pain had increased.

Global Improvement Scale Similarly, according to the global improvement scale (Figure 4), very few patients reported either being worse or experiencing no change in their back pain complaint. The overwhelming majority (93%) reported being better, although only 3 patients reported being completely so.

EQol 5 Domain Figure 5 illustrates the proportions of those patients reporting problems at baseline on the EQ-5D who improved at discharge. In all areas, there was a significant proportion of patients whose problems were not resolved, in contrast to the findings illustrated in Fig 2, Fig 3, Fig 4. This is most likely due to the fact that the EQ-5D is a generic health status measure, unlike the BQ and the Bothersomeness and global improvement scales, which are all condition specific and, therefore, more responsive to change in the patient’s back pain. This is reflected in the change in the generic health state visual analogue scale (0–100) included in the EQ-5D. Based on categorization of a significant change in health status as 30 percentage points, just over one-third (39%) of the sample reported significant improvement in their health state at discharge.

Discussion

This study evaluated a chiropractic service for back pain patients within a primary care CHC setting, which on average lasted for a period of 10 weeks. Findings indicated that this was a typical back pain population in terms of age and sex, although for this age range the proportion in paid employment was low. The relatively high proportion not in employment (66%) in this group is comparable to the findings of other investigations of chiropractic integration within Canadian CHC settings. [21, 25] In a retrospective database review from a CHC in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, [25] Passmore et al found the unemployment rate among a cohort of 177 chiropractic patients to be very high at 86%. Of 324 chiropractic patients attending 2 CHCs in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, [21]

Garner et al also found that nearly two-thirds (62%) were living at or below the poverty line. These socioeconomic findings contrast with those typically found among chiropractic patients who present in private practice settings. For instance, in 2 large studies involving patients from North America35 and the United Kingdom, [36] 68% and 82.1%, respectively, of those who used chiropractic services indicated that they were in paid employment. Unemployed patients (as well as other low-income groups) often face significant barriers to accessing chiropractic care largely because of inadequate insurance coverage. [17, 21, 25] A major implication with integrating chiropractors into publicly funded CHC settings, therefore, is that unemployed and/or economically disadvantaged individuals can gain access to chiropractic services for which most would not have otherwise.

Most of the patients in this study reported constant and more widespread pain longer than 1 month. Unlike acute back pain, which often resolves within days, subacute and chronic back pain can lead to high levels of disability and dependency. It is therefore important to manage this condition effectively as soon as possible so that these potential poor outcomes are not realized. Chronic back pain is common among complex patient populations including those of low socioeconomic status and has been reported in several studies to be significantly associated with increased comorbidity, analgesic use, health care utilization, and costs. [6–9]

In the 2 aforementioned studies of chiropractic integration in Canadian CHCs, [21, 25] musculoskeletal complaints including chronic back pain were prevalent, with the large majority of patients reporting the presence of these and other chronic health conditions. These findings are once again contrary to the typical demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who present in private chiropractic practices. [35, 36] In the study by Hurwitz and Chiang, [35] for example, the large majority of patients who used chiropractic services rated themselves in good-to-excellent health. Compared with non-chiropractic users (ie, those who visited only their general physician), chiropractic patients also reported fewer chronic health problems. [35]

The findings of the current evaluation indicated that most patients referred to this service pathway reported good outcomes at discharge. Moreover, almost all patients, irrespective of their outcome, reported high levels of satisfaction with the service. Significant improvements regarding musculoskeletal pain and/or disability were found by Garner et al [21] and Passmore et al [25] in their respective studies involving integrated chiropractic services at CHCs in Ontario and Manitoba, Canada. Similar to the current study, Garner et al [21] also found that nearly all patients (97.7%) were either very satisfied or satisfied with the chiropractic care they received. These treatment and satisfaction outcomes are in line with the findings of numerous other studies in which patients have reported positive outcomes and have been generally highly satisfied with care provided by chiropractors. [14–16, 28]

Of note, very few patients in the current study indicated that they were “completely better” at the point of discharge from this service. Despite the majority reporting that they were “much better,” the fact that most were not completely so may be a reflection of the nature of chronic back pain, which is often persistent and recurrent. [37] The finding that very few patients reported themselves as being completely better in the current study also highlights the potential challenges, and consequent need for multidisciplinary collaboration, in managing the complex needs of CHC patients. [20, 21, 23, 25]

As expected, the 3 questionnaires used in this evaluation that referred specifically to the patient’s back pain (BQ and Bothersomeness and global improvement scales) were more responsive in detecting change in the patient’s condition than the generic health status measure (EQ-5D). The EQ-5D is used mainly in studies where there is a comparator group, for example, cost-effectiveness studies, [36] to calculate a utility score and gain in quality-adjusted life years. Where there is no comparator, as was the case in this study, these calculations are not possible, so a change in the patient’s EQ-5D profile is the limit of what can be achieved. Nevertheless, the EQ-5D is a useful metric, particularly when used to compare outcomes in patients’ health status between interventions for different conditions, so as to provide evidence on which to base the prioritization of health care funds. The data from the EQ-5D were included here to illustrate how change in health status in a group of patients undergoing a particular intervention can be presented and used in future service evaluation studies.

Taken overall, it can be concluded that this particular chiropractic service resulted in improved outcomes and high levels of satisfaction in a sample of complex CHC patients with subacute and chronic back pain. These findings, as well as those of other studies involving chiropractic integration within CHC settings, [21, 24, 25] have several important implications. First and foremost, by integrating chiropractors into multidisciplinary primary care CHCs, socioeconomically disadvantaged patients gain access to chiropractic services. For instance, prior to the introduction of the current program, chiropractic had never been offered at the Langs CHC. In addition, this program only accepted patients who were not under the care of another chiropractor. Therefore, with this service, the accessibility of chiropractic care increased by 100% for this particular cohort of patients.

With chiropractic integration into primary care, the burden on medical physicians (in terms of managing all patients including those with back pain) can also be reduced, thus decreasing wait times for other patients trying to see them. In the current study, for example, more than three-quarters of patients reported that they did not seek help for their back pain from any other health provider throughout the entire course of their treatment. In theory, this would have opened up appointments for Langs’ physicians and nurse practitioners to see other patients, particularly those with more complex medical conditions. In 2011, at the Mount Carmel CHC Clinic in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, [25] chiropractic consultation visits saved 82% (132/161) of patients from making an additional appointment with their primary care physician. Furthermore, when discharged from chiropractic treatment, very few (4%) of these patients were referred to another health provider for additional care. [25] Other studies have similarly found decreases in primary care physician visits when patients were referred for chiropractic treatment. [37]

Another important implication of integrating chiropractors into primary care CHC settings is that these initiatives create interprofessional collaboration. In doing so, this can improve the quality and delivery of back pain services within these centers. For instance, there is evidence to suggest that greater communication between chiropractors and medical providers in collaborative primary care settings leads to improved continuity of care (ie, care delivered in a coordinated and timely manner). [38] Anecdotally, there was good communication between the chiropractors and medical physicians and nurse practitioners at the Langs CHC throughout the duration of this program. Because the chiropractors were integrated directly onto the Center’s electronic medical records system, chiropractic-medical provider communication was timely and efficient.

Integration of chiropractors within CHC settings also holds the potential for significant health cost savings (eg, reduced medical referrals for spine-related diagnostic imaging, surgery, and pharmaceuticals). This is particularly the case when considering the complexity of people who have chronic back pain, [6–9] including those who present within CHCs. [20, 21, 23, 25] Tracking of spine-related diagnostic imaging and surgical referrals was beyond the scope of the current service evaluation. Nevertheless, more than 8 of every 10 patients seen within the Langs clinic and followed through to discharge reported that they did not take medication or had managed to significantly reduce their medication usage for their pain with chiropractic treatment. Decreased medication usage by patients referred for chiropractic services has been previously reported in other studies as well. [14, 28, 38, 39]

In the light of the positive treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction levels reported in the current study and others,21, 25 further research and integration of chiropractic services within CHC settings are warranted. Future studies should include the number of primary care visits and diagnostic imaging and surgical referrals saved via integration. Qualitative investigation of physicians’ and/or other health providers’ attitudes toward chiropractors and their inclusion within multidisciplinary CHC teams should also be explored.24

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the relatively small number of patients that were recruited and followed through to discharge. In all pragmatic studies, which, by their nature, are not conducted in a highly controlled research environment, there is likely to be a relatively high number of dropouts, as was the case here. Although we did not impute any values for missing data in the follow-up period, we are not aware of any systematic differences between those patients who did and did not complete follow-up questionnaires. For example, there were no differences in sex, age, and severity of their condition (as measured by baseline total BQ scores) between these 2 patient samples.

A further limitation is there was no control or comparator group. Therefore, it is unclear if the patients’ outcomes were as a result of their treatment(s). It is also possible that some patients may have been predisposed to respond favorably because this was a complimentary chiropractic service. In keeping with all health service evaluation studies, [26] this study describes what happens to patients undergoing treatment rather than “cause and effect,” which can only be investigated using a controlled design.

Regardless, the vast majority of patients in this study reported having pain for more than 1 month (and many for considerably longer). It is therefore unlikely that natural history accounted in any significant manner for the outcomes observed. Finally, in line with health service evaluation designs, [26] the strength of this study resides in the real-time evaluation of a locally based new service rather than in determining the efficacy of a treatment intervention. As such, caution is required in extrapolating the findings to other care pathways.

Conclusion

This study evaluated a new back pain service provided by chiropractors integrated into a primary care CHC setting. Overall, this service was associated with high levels of improvement and patient satisfaction in a sample of complex CHC patients with subacute and chronic back pain. These outcomes, including those of other studies, may have important implications for patients, policy decision makers, and health care stakeholders. Future research of chiropractic services within CHC settings is warranted.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

This project was supported by a research grant from the Ontario Chiropractic Association.

P.C.E. received a research grant from the Ontario Chiropractic Association for data collection, literature searching, and writing of this manuscript. A portion of this grant was also paid to the Anglo-European College of Chiropractic for statistical analysis.

No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): P.C.E., J.E.B.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): P.C.E., J.E.B.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): P.C.E.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): P.C.E., A.L.B., D.F.C., A.F.P.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): J.E.B.

Literature search (performed the literature search): P.C.E. Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): P.C.E., J.E.B.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): P.C.E., A.L.B., D.F.C., A.F.P., J.E.B.

References:

Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al.

A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain.

Arthritis Rheum. 2012; 64(6):2028-2037.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al.

Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) for 1160 Sequelae of 289 Diseases and Injuries

1990-2010: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

Lancet. 2012 (Dec 15); 380 (9859): 2163–2196Hart LG, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC.

Physician office visits for low back pain: Frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns

from a U.S. national survey.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(1):11-19.Woolf AD, Pfleger B.

Burden of Major Musculoskeletal Conditions

Bull World Health Organ 2003 (Nov 14); 81: 646–656Economic burden of illness in Canada, 2005-2008.

Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2013. Available at:

http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ebic-femc/2005-2008/assets/ pdf/ebic-femc-2005-2008-eng.pdf

Accessed April 27, 2016.Ritzwoller DP, Crounse L, Shetterly S, Rublee D.

The association of comorbidities, utilization and costs for patients

identified with low back pain.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:72.Gore M, Sadosky A, Stacey BR, Tai KS, Leslie D.

The Burden of Chronic Low Back Pain: Clinical Comorbidities, Treatment Patterns,

and Health Care Costs in Usual Care Settings

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 (May 15); 37 (11): E668–677Bath B, Trask C, McCrosky J, Lawson J.

A biopsychosocial profile of adult Canadians with and without chronic back disorders:

A population-based analysis of the 2009-2010 Canadian Community Health Surveys.

Biomed Res Int. 2014; 2014:919621.Shmagel A, Foley R, Ibrahim H.

Epidemiology of chronic low back pain in US adults:

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2010.

Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(11):1688-1694.Bronfort G Haas M Evans RL et al.

Efficacy of Spinal Manipulation and Mobilization for Low Back Pain and Neck Pain:

A Systematic Review and Best Evidence Synthesis

Spine J (N American Spine Soc) 2004 (May); 4 (3): 335–356Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leiniger B, Triano J.

Effectiveness of Manual Therapies: The UK Evidence Report

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2010 (Feb 25); 18 (1): 3Liliedahl RL, Finch MD, Axene DV, Goertz CM.

Cost of Care for Common Back Pain Conditions Initiated With Chiropractic

Doctor vs Medical Doctor/Doctor of Osteopathy as First Physician:

Experience of One Tennessee-Based General Health Insurer

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Nov); 33 (9): 640–643Weeks WB, Leininger B, Whedon JM, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, Swenson R, et al.

The Association Between Use of Chiropractic Care and Costs of Care Among

Older Medicare Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain and Multiple Comorbidities

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(2):63–75Houweling TA, Braga AV, Hausheer T, Vogelsang M, Peterson C, Humphreys BK.

First-Contact Care With a Medical vs Chiropractic Provider After

Consultation With a Swiss Telemedicine Provider: Comparison

of Outcomes, Patient Satisfaction, and Health Care Costs in

Spinal, Hip, and Shoulder Pain Patients

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(7):477-483.Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ.

Integration of Chiropractic Services in Military and Veteran Health Care Facilities:

A Systematic Review of the Literature

J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016 (Apr); 21 (2): 115–130Gaumer G.

Factors Associated With Patient Satisfaction With Chiropractic Care:

Survey and Review of the Literature

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006 (Jul); 29 (6): 455–462Manga, P.

Economic Case for the Integration of Chiropractic Services into the Health Care System

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2000 (Feb); 23 (2): 118–122Excellent care for all: Low back pain strategy.

Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-TermCare; 2014. Available at:

http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ecfa/

action/primary/lower_back.aspx

Accessed April 29, 2016.Chiropractic in the health system: Primary care

low back pain pilot programs.

Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Chiropractic Association; 2014. Available at:

https://www.chiropractic.on.ca/chiropractic-in-the-health-system#a2.

Accessed May 2, 2016.Community Health Centres.

Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2015. Available at:

https://www.ontario.ca/page/community-health-centres

Accessed April 22, 2016.Garner MJ, Aker P, Balon J, et al.

Chiropractic Care of Musculoskeletal Disorders in a Unique

Population Within Canadian Community Health Centers

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Mar); 30 (3): 165–170About Langs.

Cambridge: Langs Community Health Centre; 2016. Available at:

http://www.langs.org/about-langs/

Accessed April 22, 2016.Baskerville NB, Keenan D.

How chiropractors began working in a Community Health Centre in Ottawa.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2005;49(1):13-20.Garner MJ, Birmingham M, Aker P, Moher D, Balon J, Keenan D, Manga P.

Developing Integrative Primary Healthcare Delivery:

Adding a Chiropractor to the Team

Explore (NY). 2008 (Jan); 4 (1): 18–24Passmore SR, Toth A, Kanavosky J, Olin G.

Initial Integration of Chiropractic Services into a Provincially Funded

Inner City Community Health Centre: A Program Description

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2015 (Dec); 59 (4): 363–372Twycross A, Shorten A.

Service evaluation, audit and research: What is the difference?

Evid Based Nurs. 2014; 17(3):65-66.Globe, G, Farabaugh, RJ, Hawk, C et al.

Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 1–22Gurden M, Morelli M, Sharp G, Baker K, Betts N, Bolton J.

Evaluation of a general practitioner referral service for manual treatment of back and neck pain.

Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2012;13(3):204-210.Bolton JE, Breen AC.

The Bournemouth Questionnaire: A Short-form Comprehensive Outcome Measure.

I. Psychometric Properties in Back Pain Patients

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1999 (Oct); 22 (8): 503-510Dunn KM. Croft PR.

Classification of Low Back Pain in Primary Care: Using "Bothersomeness"

to Identify the Most Severe Cases

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005 (Aug 15); 30 (16): 1887–1892EuroQol Group.

EuroQol—A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life.

Health Policy. 1990; 16(3):199-208.Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, et al.

Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain:

Towards international consensus regarding minimal important change.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(1):90-94.Devlin N, Parkin D, Browne J.

Patient-reported outcome measures in the NHS:

New methods for analysing and reporting EQ-5D data.

Health Econ. 2010;19(8):886-905.Gutacker N, Bojke C, Daidone S, Devlin N, Street A.

Analysing hospital variation in health outcome at the level of EQ-5D dimensions.

York, United Kingdom: Centre for Health Economics; 2012. Available at:

http://www.york.ac.uk/che/ news/archive-2014/research-paper-74/

Accessed April 22, 2016.Hurwitz EL, Chiang LM.

A Comparative Analysis of Chiropractic and General Practitioner

Patients in Noth America: Findings From the Joint Canada/

United States Survey of Health, 2002-03

BMC Health Serv Res 2006 (Apr 6); 6: 49Newell D, Diment E, Bolton JE.

An electronic patientreported outcome measures system in UK chiropractic practices:

A feasibility study of routine collection of outcomes and costs.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(1):31-41.Cassidy JD, Côté P, Carroll LJ, Kristman V.

Incidence and course of low back pain episodes in the general population.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(24):2817-2823.Mior S, Gamble B, Barnsley J, Côté P, Côté E.

Changes in Primary Care Physician's Management of Low Back Pain

in a Model of Interprofessional Collaborative Care:

An Uncontrolled Before-After Study

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2013 (Feb 1); 21 (1): 6Rhee Y, Taitel MS, Walker DR, Lau DT.

Narcotic drug use among patients with lower back pain in employer health plans: A retrospective analysis of risk factors and health care services.

Clin Ther. 2007;29(Suppl):2603-2612.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to PATIENT SATISFACTION

Return to INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE

Since 10-06-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |