When Boundaries Blur - Exploring Healthcare Providers'

Views of Chiropractic Interprofessional Care

and the Canadian Forces Health ServiceThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2020 (Dec); 50 (12): 657-660 ~ FULL TEXT

Mary O'Keeffe, Adrian C Traeger, Zoe A Michaleff, Simon Décary, Alessandra N Garcia, Joshua R Zadro

Institute for Musculoskeletal Health,

Sydney Local Health District,

Camperdown, Australia

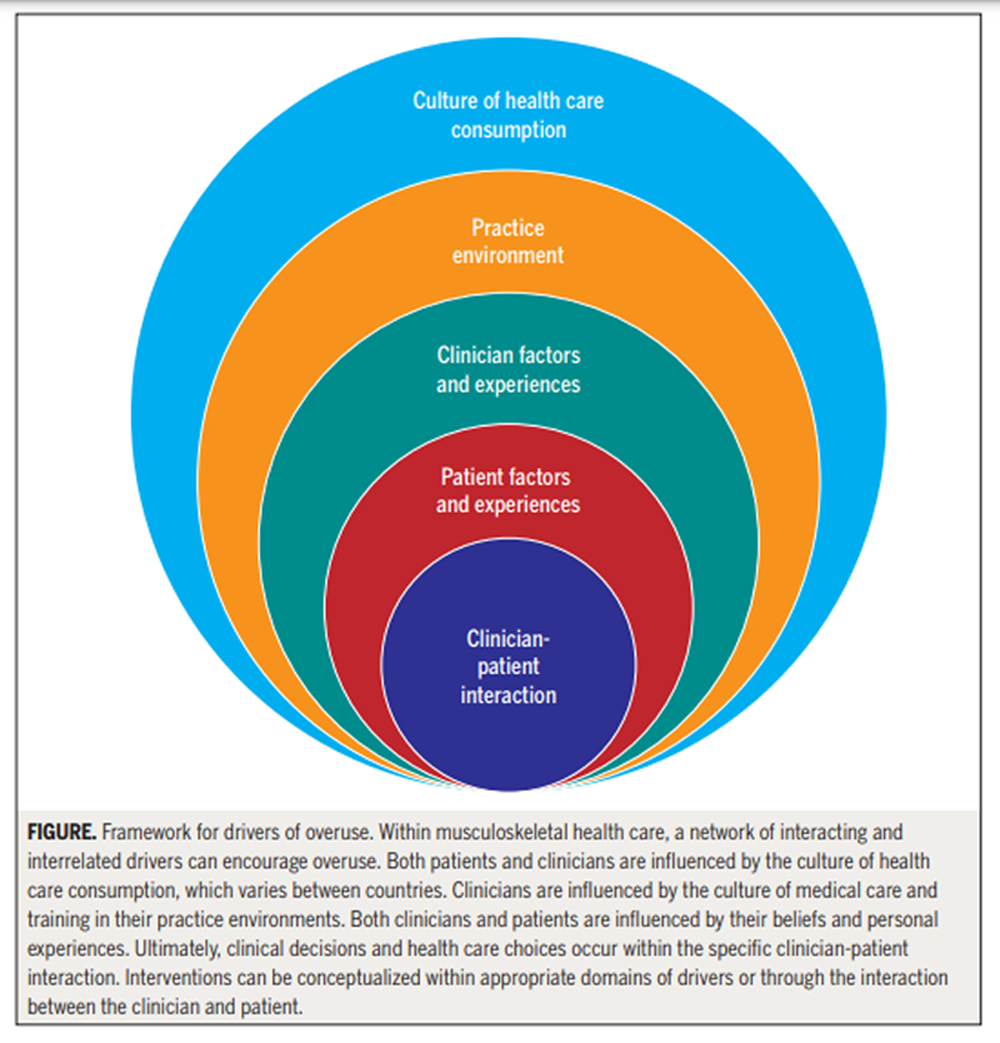

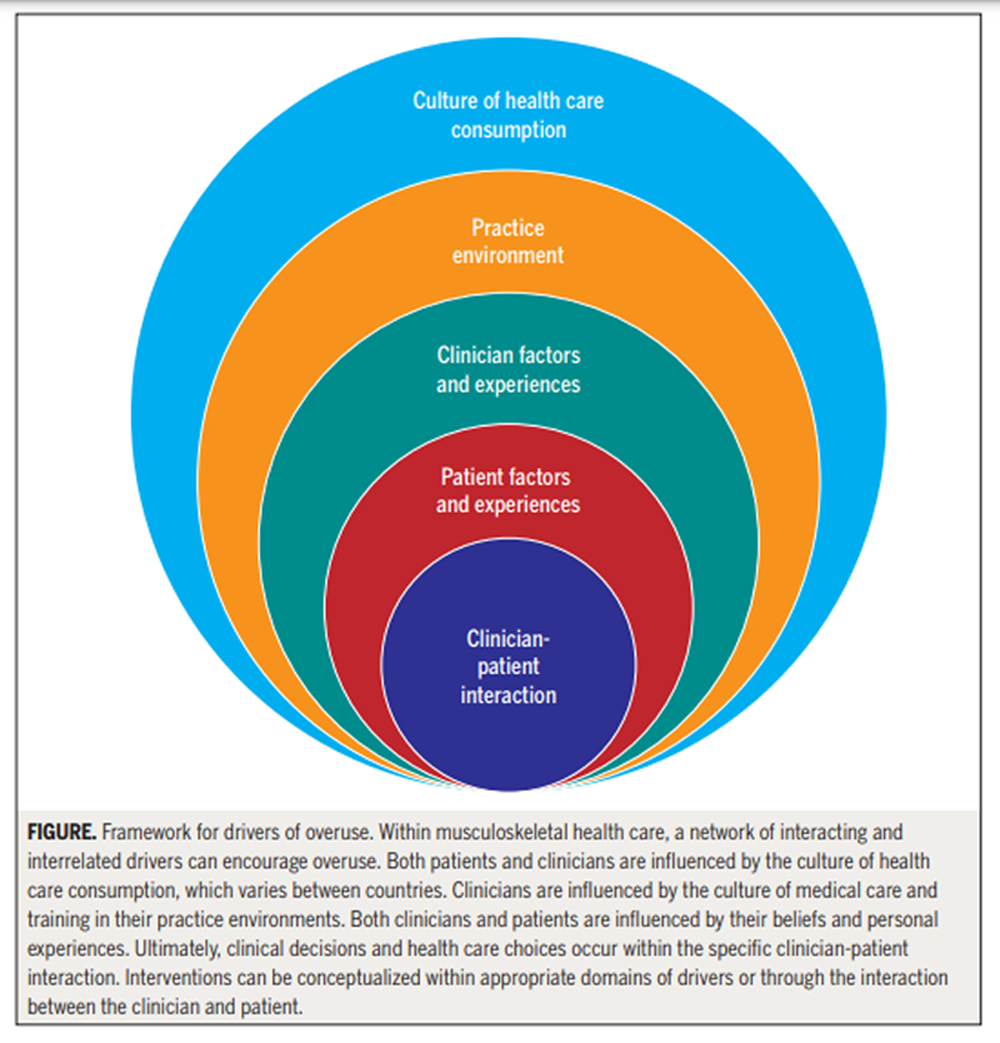

Overcoming overuse in musculoskeletal health care requires an understanding of its drivers. In this, the third article in a series on "Overcoming Overuse" of musculoskeletal health care, we consider the drivers of overuse under 4 domains: (1) the culture of health care consumption, (2) patient factors and experiences, (3) clinician factors and experiences, and (4) practice environment. These domains are interrelated, interact, and influence the clinician-patient interaction. We map drivers to potential solutions to overcome overuse.

Keywords: drivers; musculoskeletal; overuse; physical therapy.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Table

Page 2

Figure In the Overcoming Overuse series so far, we have discussed what overuse is in musculoskeletal health care, how it happens, and the challenges of identifying and measuring overuse in physical therapy. Here, we focus on the drivers of overuse, why musculoskeletal health care overuse emerges.

There are many drivers of overuse, yet their relative importance, how they interact, or the potential value of targeting any single driver is unclear. We apply a practical framework10 for understanding overuse of musculoskeletal care (TABLE), and propose a network of interacting and interrelated drivers of overuse of musculoskeletal care in 4 domains: (1) the culture of health care consumption, (2) patient factors and experiences, (3) clinician factors and experiences, and (4) practice environment (FIGURE). We place the clinician-patient interaction at the center of our patient-centered network — where the multiple drivers of overuse of musculoskeletal care connect and exert their influence — and hope to inspire musculoskeletal research to produce interventions to tackle overuse.

The Culture of Health Care Consumption

Misleading marketing, poor online information, and uncritical media reporting can promote overuse. “More is better,” “new is better,” and “technology is good” are popular beliefs that promote health care overuse. The messages are reinforced by pharmaceutical and device companies, and by health professionals selling tests and treatments. Medical marketing of prescription drugs, health services, laboratory tests, and disease awareness campaigns in the United States—to both clinicians and the public—reached $30 billion in 2016, up from $18 billion in 1997. [12] There is little evidence that increased spending has improved healthrelated outcomes. The physical therapy profession is not immune; some have raised concerns that marketing initiatives could lead to unnecessary physical therapy for conditions such as back pain. [15]

The internet — awash with unreliable information — is a breeding ground for overuse. An analysis of publicly available information on knee arthroscopy for osteoarthritis (a procedure that offers no benefit over placebo) in Australia found that only 6 of 93 documents cited research and only 8 of 93 advised against arthroscopy. [2] A study of information about low back pain on websites deemed to be “trustworthy” found that fewer than half of the treatment recommendations were accurate according to UK and US clinical guidelines. [4]

The media can contribute to overuse via uncritical enthusiasm for health care. [6] Headlines like “Breakthrough in back pain care as stem cells offer hope of cure” give hope, but evidence for the benefit of stem cell treatments is limited.

Sensationalizing inaccurate information through media, marketing, and the internet impedes informed choices about management and perpetuates blind faith in the benefits of health care.

Patient Factors and Experiences

Beliefs about musculoskeletal pain and enthusiasm for new tests and treatments may leave patients vulnerable to overuse. Patient beliefs influence treatment expectations and intentions. Patients with knee osteoarthritis disregarded the role of exercise—in favor of unproven medical treatments—for fear of doing more damage.3 Receiving structural diagnoses for shoulder pain (eg, impingement) and back pain (eg, degeneration) may increase patients’ willingness to undergo surgery.

Patients often overestimate the benefits and underestimate the downsides of health care.7 People diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis perceive they will experience greater benefit from injections and medicines compared to exercise.11 Patients often believe that imaging will lead to more effective back pain treatment.8

Low health literacy has been associated with unnecessary health care use and could impact use of physical therapy.5 Patient expectations of physical therapy and preferences for specific interventions (eg, manipulation)1 may also influence the acceptability of recommended options (eg, home exercise).

Clinician Factors and Experiences

Biomedical and biomechanical treatment paradigms, the belief that more care is better, and fear of inaction may encourage overuse. In physical therapy, management paradigms for various musculoskeletal conditions are dominated by identifying “abnormalities” in posture and alignment, among others.9 Most abnormalities have little to no association with pain or disability, challenging the use of corrective exercises. If physical therapists are movement specialists and corrective exercises do not work, what is the benefit of specialized one-to-one physical therapy over a general low-cost exercise program?

Beliefs that more care is better, action is better than inaction, and “group think” (“My colleagues use dry needling, so I should, too”) might discourage clinicians from adhering to management guidelines. The view that clinical experience triumphs over research evidence is evident in low physical therapist compliance with guidelines for back pain, ankle sprains, and whiplash.14

Fear of inaction could promote overuse and may relate to concerns about the negative impact on the clinicianpatient interaction, missing a diagnosis, or litigation. In a 2017 Choosing Wisely Australia report, 73% of physical therapists were willing to order unnecessary imaging if requested by patients. One potential solution to fear of inaction in physical therapy is empowering patients to self-manage through home exercise. In this role, physical therapists can act as a “guide” rather than providing excessive supervised treatment.

The Practice Environment

Time constraints, funding arrangements, practice design, and vested interests can perpetuate overuse. Brief physician consultations are a barrier to providing important aspects of care, such as listening and reassurance.13 Quickly ordering a scan and prescribing medicine are appealing options. The perception that physicians should be the first point of contact within the health care system might encourage these behaviors. Physical therapists have more time to spend with patients with musculoskeletal conditions to provide recommended care and should be considered an appropriate point of contact.

Health system regulation, reimbursement, and commissioning of health services may be incentives to overservice and provide nonrecommended care. In the United States, the fee schedule that Medicare and private payers use tends to underpay for time and overpay for tests and procedures. We address economic drivers of overuse and vested interests later in the Overcoming Overuse series.

The practice environment may make it easier for clinicians to prescribe an unnecessary test or treatment, or more difficult to prescribe recommended care. For example, electronic health record display — if designed in a haphazard manner — can make it so that a large packet of opioids is the default option. For physical therapists, lack of space may hamper efforts to provide the exercise recommended in the guidelines for musculoskeletal conditions (eg, knee osteoarthritis).

In this article, we have discussed the key drivers of musculoskeletal health care overuse. We contend that many drivers exert their influence at the clinicianpatient level—highlighting the potential value of a shared decision-making

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

All authors conceived the idea. Dr O’Keeffe wrote the first draft. All authors contributed intellectual content, assisted with revisions, and approved the final version of this editorial.

References:

Bishop MD, Mintken PE, Bialosky JE, Cleland JA.

Patient expectations of benefit from interventions

for neck pain and resulting influence on outcomes.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43:457-465.

https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2013.4492Buchbinder R, Bourne A.

Content analysis of consumer information about knee arthroscopy in Australia.

ANZ J Surg. 2018;88:346-353.

https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.14412Bunzli S, O’Brien P, Ayton D, et al.

Misconceptions and the acceptance of evidence-based nonsurgical

interventions for knee osteoarthritis. A qualitative study.

Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477:1975-1983.

https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000000784Ferreira G, Traeger AC, Machado G, O’Keeffe M, Maher CG.

Credibility, accuracy, and comprehensiveness of internet-based

information about low back pain: a systematic review.

J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e13357.

https://doi.org/10.2196/13357Griffey RT, Kennedy SK, McGowan L, Goodman M, Kaphingst KA.

Is low health literacy associated with increased

emergency department utilization and recidivism?

Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:1109-1115.

https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12476Grilli R, Ramsay C, Minozzi S.

Mass media interventions: effects on health services utilisation.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD000389.

https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000389Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C.

Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of

treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review.

JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:274-286.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6016Jenkins HJ, Hancock MJ, Maher CG, French SD, Magnussen JS.

Understanding patient beliefs regarding the use of

imaging in the management of low back pain.

Eur J Pain. 2016;20:573-580.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.764Maher CG, O’Keeffe M, Buchbinder R, Harris IA.

Musculoskeletal Healthcare: Have we Over-egged the Pudding?

International J Rheumatic Diseases 2019 (Nov); 22 (11): 1957–1960Morgan DJ, Leppin AL, Smith CD, Korenstein D.

A practical framework for understanding and reducing medical overuse:

conceptualizing overuse through the patient-clinician interaction.

J Hosp Med. 2017;12:346-351.

https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2738Posnett J, Dixit S, Oppenheimer B, Kili S, Mehin N.

Patient preference and willingness to pay for knee osteoarthritis treatments.

Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:733-744.

https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S84251Schwartz LM, Woloshin S.

Medical marketing in the United States, 1997-2016.

JAMA. 2019;321:80-96.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.19320Slade SC, Kent P, Patel S, Bucknall T, Buchbinder R.

Barriers to primary care clinician adherence to clinical guidelines

for the management of low back pain: a systematic review

and metasynthesis of qualitative studies.

Clin J Pain. 2016;32:800-816.

https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000324Zadro JR, Ferreira G.

Has physical therapists’ management of musculoskeletal conditions improved over time?

Braz J Phys Ther. 2020;24:458-462.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2020.04.002Zadro JR, O’Keeffe M, Maher CG.

Evidence-based physiotherapy needs evidence-based marketing.

Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:528-529.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099749

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Since 3-14-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |