The Difference Between Integration and Collaboration

in Patient Care: Results From Key Informant Interviews

Working in Multiprofessional Health Care TeamsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 (Nov); 32 (9): 715–722 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Heather S. Boon, PhD, Silvano A. Mior, DC, Jan Barnsley, PhD,

Fredrick D. Ashbury, PhD, Robert Haig, DC

Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy,

University of Toronto,

Toronto, Canada.OBJECTIVES: Despite the growing interest in integrative health care, collaborative care, and interdisciplinary health care teams, there appears to be little consistency in terminology and clarity regarding the goal for these teams, other than "working together" for the good of the patients. The purpose of this study was to explore what the terms integration and collaboration mean for practitioners and other key informants working in multiprofessional health care teams, with a specific look at chiropractic and family physician teams in primary care settings.

METHODS: Semistructured interviews were conducted with 16 key informants until saturation was obtained in the key emerging themes. All interviews were audiorecorded, and the transcripts were coded using qualitative content analysis.

RESULTS: Most participants differentiated collaboration from integration. They generally described a model of professions working closely together (ie, collaborating) in the delivery of care but not subsumed into a single organizational framework (ie, integration). Our results suggest that integration requires collaboration as a precondition but collaboration does not require integration.

CONCLUSIONS: Collaboration and integration should not be used interchangeably. A critical starting point for any new interdisciplinary team is to articulate the goals of the model of care.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic, Medicine, Integrative Medicine, Delivery of Health Care, Integrated, Qualitative Research

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

The evolution from the traditional mechanistic view of the human body to one encompassing a biopsychosocial approach has come about as a result of a greater understanding of the interrelationship between health, illness, and disease. [1–3] This view has moved the focus from the health care provider to the patient in an effort to appreciate the complexity of the multiple dimensions underlying the interplay between patient's illness and disease, thus capturing the indivisible whole of the healing relationship. [4] This inherent complexity of human health requires the involvement of individuals with disparate expertise collaborating in multidisciplinary teams to provide the best patient care. For example, the Ontario government is establishing primary health care teams across the province to provide comprehensive and coordinated care to meet the needs of patients. [5] The integration of different health services has been highlighted as a common strategy to address the delivery of effective and cost-effective comprehensive care. [6–10] However, the increasing number of different heath-related disciplines bringing unique insight to the care of patients challenges integration, with the absence of training in collaborative team methodologies. [11]

Despite the growing interest and amount of literature on the topics of integrative care, collaborative care, and interdisciplinary health care teams, there appears to be little consistency in terminology and clarity regarding the goal for these teams, other than “working together” for the good of the patients. To contribute to a definition, this article explores what the terms integration and collaboration mean for practitioners and other key informants working in multiprofessional health care teams, with a specific look at chiropractic and family physician teams in primary care settings. Our study permits conclusions about goals for the relationships among teams comprising disparate health care professions.

Collaborative care (ie, the collaboration of different health care providers in the delivery of patient care) has been proposed as the answer to many complex health care issues including growing resource constraints, increasing rates of chronic illnesses, and a growing and aging population. [12–14] However, there are almost as many definitions of collaborative care as there are authors that have discussed purported benefits. For example, Sullivan [15] (1998) applied concept analysis to definitional terms found in the literature to identify collaboration as “a dynamic, transforming process of creating a power sharing partnership for pervasive application in health care practice, education, research, and organizational settings for the purposeful attention to needs and problems in order to achieve likely successful outcomes” (p. 6).

Way et al [16] described collaborative care as “… an interprofessional process for communication and decision making that enables the separate and shared knowledge and skills of care providers to synergistically influence the client/patient care provided.” Similarly, interdisciplinary collaboration has been described as the “process by which individuals from different professions structure a collective action in order to coordinate the services they render to individual clients or groups” (p. 992) [17] and as conveying “the idea of sharing and implies collective action oriented toward a common goal, in a spirit of harmony and trust, particularly in the context of health professionals” (p. 116). [10]

It has been argued that different types or levels of collaboration may occur among the same team members in different situations. Another approach is a focus on how different levels of collaboration may differentiate types of teams and their interactions. For example, Hudson [18] considered the level of communication and the organizational structure to differentiate between progressively more involved levels of collaboration, such as simple communication, coordination, colocation, and commissioning. In contrast, Kinnaman and Bleich [13] (2004) applied complex systems theory to identify different types of collaboration based upon the level of need for interprofessional agreement/involvement and certitude of clinical outcome. Their model defined 4 levels of progressively greater interprofessional involvement, namely, toleration, coordination, cooperation, and collaboration. These models describe a continuum where the highest level of collaboration may be attained when inequities in power, decision-making, professional boundaries, and hierarchy are transcended.

In another approach, Boon et al [19] propose a continuum of ways in which team members interact. They identified 7 different levels, where each one is differentiated by increased levels of interprofessional interaction, involvement in the delivery of care, and the nature of the organizational structure and processes. These different levels range from parallel practice to collaboration to integration, with collaboration falling in the middle of the continuum. The continuum of Boon et al identifies “integration” rather than “collaboration” as the ultimate goal of teams working together to solve complex patient care problems. One problem in distinguishing collaboration from integration is that many authors like Boon et al appear to assume the terms essentially describe the same phenomenon, that is, describe the ways in which team members interact without taking into account the context of those activities. Often, the term collaboration is used as part of the definition of integration and vice versa.

Integration is another term with numerous definitions in the literature and is not limited to multiple health care professionals trained in conventional, biomedical care of patients. [20] Boon et al identified more than 50 articles that attempted to describe how complementary and alternative health care was being combined with conventional biomedical care. These authors identified that most definitions of integration comprised combinations of 4 components:(1) philosophy or values,

(2) structure,

(3) process, and

(4) outcomes.Their qualitative content analysis of definitions in the literature resulted in what is defined as a working definition of integration as a goal or ideal type (as opposed to a description of a concrete model of how care is currently being delivered). According to Boon et al, integration:

Seeks, through a partnership of patient and practitioner, to treat the whole person, to assist the innate healing properties of each person, and to promote health and wellness as well as the prevention of disease (philosophy and/or values).

Is an interdisciplinary, nonhierarchical blending of both conventional medicine and complementary and alternative health care that provides a seamless continuum of decision-making, patient-centered care, and support (structure).

Uses a collaborative team approach guided by consensus building, mutual respect, and a shared vision of health care that permits each practitioner and the patient to contribute their particular knowledge and skills within the context of a shared, synergistically charged plan of care (process).

Results in more effective and cost-effective care by synergistically combining therapies and services in a manner that exceeds the collective effect of the individual practices (outcomes) (p. 55).20

A more succinct definition of integration from the Program in Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona is

“Integrative medicine [is] healing oriented medicine that takes account of the whole person (body, mind and spirit), including all aspects of lifestyle. It emphasizes the therapeutic relationship and makes use of all appropriate therapies, both conventional and alternative.” [21]

A similar definition is that it

“seeks to combine the best insights of both conventional and alternative medicine, while providing a unifying perspective to guide physicians in intelligently combining these heterogeneous systems of thought” (p. 1085). [22]

These 2 definitions raise one of the current debates within the literature: the role of the physician in integrative care or what is often called integrative medicine or integrated care/medicine. The debate concerns whether or not integrative care delivery requires a multidisciplinary team or simply reflects a single health care practitioner incorporating different therapies in patient care.

Although the terms care and medicine are often used interchangeably, the use of care instead of medicine in the label may reflect an author's views on the centrality of physicians in health care delivery systems. Another aspect of the definitional confusion is whether the terms integrative and integrated are interchangeable or have unique meanings. In this article, we choose to use integrative care to signify that we are interested in a team process that includes multiple players from different disciplines.

Hsiao et al [23] identified that health care practitioners do have a range of conceptions of integrative care, many not fully consistent with the “official” definition of the study coordinators. Some practitioners thought the goal of integration was to “harmonize the biomedical and CAM paradigms into a single unified paradigm” (p. 2981). [23] In contrast, others felt that it was vital to maintain distinct paradigms while the different practitioners are working together, as one participant of the study explains: “A certain amount of integrative medicine is healthy and to a certain degree when it's too integrated, then you lose the essence and beauty of each [paradigm]” (p. 2981). [23]

A practical problem raised by this debate over terminology is as follows: What is the goal of working together? When teams of caregivers want to work together, what are they trying to achieve: collaboration or integration? And what, practically, should that look like? Establishing the parameters concerning goal setting was a key challenge facing our research team when we set out to develop a model of care in which chiropractors and physicians work together in a primary care setting.

It has been estimated that 12% of Canadians [24] and 35% of Canadians with musculoskeletal disorders, [25] as well as 7.5% of Americans, [26] visit chiropractors each year. Evidence-based guidelines and reviews have acknowledged the effectiveness of manual therapy, the main treatment intervention provided by chiropractors, in the management of back and neck pain. [27–31] The implementation of these types of guidelines may result in improved outcomes in the management of back pain and potentially save considerable direct and indirect costs. However, one barrier to including chiropractic services in patient care plans is that chiropractors, like other allied health professions, tend to set up offices independent of other health care providers, which may limit their ability to work with them. [26]

A growing number of projects exploring the inclusion of chiropractic services in multidisciplinary settings, particularly in the United States, have met with varied success. [32–38] Barriers to the inclusion of chiropractic services include provider competition and bias, philosophical differences, physicians' lack of knowledge of the intervention, lack of or limited evidence in support of clinical efficacy, cultural bias and prejudice, and lack of funding for services. [39–44] These barriers result in limited referrals and utilization of chiropractic care, or patients seeking care without the knowledge of their general physician. [45]

This article reports on the first phase of a multiphase study in which a model of care with physicians and chiropractors working together was developed, implemented, and assessed. The purpose of this part of the study was to propose a model for how chiropractors and physicians might work together in a primary health care setting. However, a critical barrier to model development was the lack of clarity over whether our goal was to develop a model of collaboration or a model of integration. This article describes our investigation of key stakeholders' perceptions of these 2 terms and their recommendations with respect to our goal.

Discussion

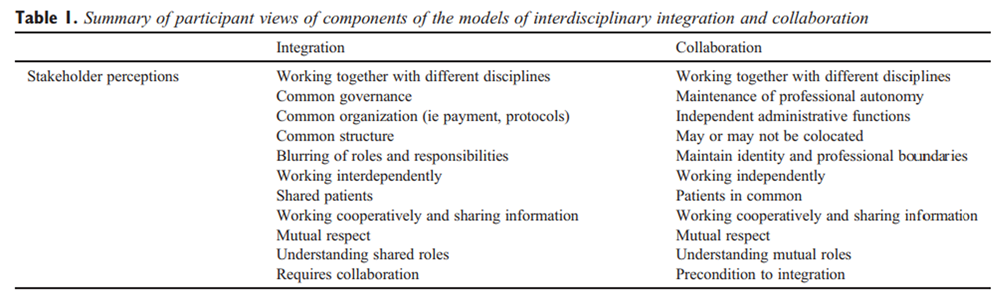

Our findings reveal differences in stakeholder perceptions of the terms collaboration and integration, suggesting that these terms must be defined to avoid confusion in discussions of interdisciplinary patient care (Table 1). Participants in this study generally supported the creation of a model of care that enhanced working relationships between chiropractors and physicians in a primary care setting. However, any model that resulted in perceived loss of autonomy by any participant was generally considered less desirable.

One of the tensions throughout the integrative medicine literature is whether integrative medicine is by definition an interdisciplinary endeavor or whether a single practitioner (such as a physician) can practice integrative medicine alone. Can integrative medicine be a medical specialty similar to internal medicine or pediatrics?

A similar concern with maintaining professional autonomy was identified in an examination of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners and physicians working together in biomedical settings (hospitals) in Israel. [52] The authors of this study describe how the medical profession identified and secured boundaries around the work of the CAM practitioners as a mechanism for the inherent preservation of mainstream professional identity (eg, autonomy and power) while at the same time enabling medical professionals to avoid overt confrontations with CAM practitioners. All the physicians in the study expressed explicit support and respect for the CAM practitioners working with them at the hospital. However, the study describes a multidimensional process they term boundary at-work by which the physicians excluded CAM practitioners from formal structures within the workplace setting or discourses about knowledge (ie, what constitutes truth).

This situation allows the 2 groups of practitioners to work together in the same physical space, but prevents any need to engage in discussions of “alternative” forms of knowledge or what the authors call epistemological integration. [52] Sicotte et al [17] (2002) describe a tension between “disciplinary logic” and “interdisciplinary logic” in Quebec community health care centers. Although professionals do value interdisciplinary collaboration and the associated benefits, they tend to retreat to traditional professional models when their territory is threatened. The preference for collaboration over integration identified in our study may be an example of an unwillingness to threaten professional boundaries by either the chiropractors or the physicians.

Shuval and Mizrachi [53](2004) suggest that organizational boundaries (ie, physically working together) are much easier to redefine than cognitive boundaries. Cognitive boundaries appear to be more difficult to change, and it is these boundaries that are used by the dominant group to maintain jurisdictional control when groups attempt to work cooperatively. In our study, the practitioners often talked about the drawbacks of integration in structural terms (ie, integration is health care under a single structure); but in essence, they appear to be most concerned about changing cognitive boundaries to achieve the epistemological integration that was identified as unachievable in the Israeli study. Boon et al [19] also identified that a hallmark of integrative care is an interdependence in both structure and process, and a confluence of providers' philosophies and values. In contrast, collaboration involves structures and processes that are more cooperative and that preserve the uniqueness of philosophy and values of the players. In our study, hesitancy to move toward epistemological integration was identified from both the chiropractors and the physicians.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is that our findings are derived from a relatively small sample of North American practitioners, academics, and researchers with a focus on chiropractic/physician primary care teams and thus may not be generalizable to other jurisdictions or practitioner groups. Because our research question was very focused, we were able to reach saturation in the key qualitative themes emerging from the data with relatively few participants. However, the literature suggests that issues similar to those raised by our participants exist across North America when practitioners from different disciplines try to work together. This hypothesis should be tested in a larger, comparative study, including other health care professions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, participants generally described a model of professions working closely together in the delivery of care (ie, collaboration) but not being subsumed into a single organizational framework (ie, integration). Our participants suggest that, whereas integration requires collaboration as a precondition, collaboration does not require integration. Collaborative practice has been proposed as a means by which interdisciplinary health care teams can work together and has been defined as “… an inter-professional process for communication and decision-making that enables the separate and shared knowledge and skills of health care providers to synergistically influence the client/patient care provided” (p. 3). [16] This definition is consistent with preferences expressed by the practitioners in this study. It is also characteristic of other similar models such as that in mental health and primary care54 and in nursing. [16] A critical starting point for any new interdisciplinary team is to clearly articulate the goals of the model of care.

References:

de Haes, H.

Dilemmas in patient-centeredness and shared decision making:

a case for vulnerability.

Patient Educ Couns. 2006; 62: 291–298Engel, GL.

The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine.

Science. 1977; 196: 129–136Johnson, C, Baird, R, Dougherty, PE, Globe, G, Green, BN et al.

Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008; 31: 397–410Stewart, M.

Towards global definition of patient centred care.

BMJ. 2001; 322: 444–445Smitherman, G.

Ontario's transformation plan: purpose and progress.

Speaking notes for Minister of Health and Long Term Care.

St. Lawrence Market North Building.

http://www.longwoods.com/opinions/SmithermanSept-04.pdf

Date: 2004Institute of Medicine of the National Academies.

Complementary and alternative medicine in the United States.

The National Academies press, Washington, DC; 2005Romanow, R.

Building on values: the future of health care in Canada—final report:

Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada.

Health Canada, Ottawa; 2002Kirby, M.

The health of Canadians—the federal role. (Available from:)

Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology, Ottawa; 2001

www.parl.gc.caWorld Health Organization.

Primary health care: now more than ever (2008).

WHO Press, Geneva; 2008Oandasan, I, Baker, R, Barker, K et al.

Teamwork in health care: promoting effective teamwork in healthcare in Canada—policy

synthesis and recommendations.

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, Ottawa; 2006Pringle, D, Levitt, C, Horsburgh, M, Wilson, R, and Whittaker, M.

Interdisciplinary collaboration and primary health care reform.

Can J Public Health. 2000; 91: 85–86Howes, J, Sullivan, D, Lai, N et al.

The effects of dietary supplementation with isoflavones from red clover on the

lipoprotein profiles of post menopausal women with mild to moderate hypercholesterolaemia.

Atherosclerosis. 2000; 152: 143–147Kinnaman, M and Bleich, M.

Collaboration: aligning resources to create and sustain partnerships.

J Prof Nurs. 2004; 20: 310–322Holgers, KM, Axelsson, A, and Pringle, I.

Ginkgo biloba extract for the treatment of tinnitus.

Audiology. 1994; 33: 85–92Sullivan, T.

Collaboration: a health care imperative.

McGraw-Hill, New York; 1998Way, D, Jones, L, and Busing, N.

Implementation strategies: “collaboration in primary care—family doctors & nurse

practitioners delivering shared care”.

The Ontario College of Family Physicians, Toronto; 2000Sicotte, C, D'Amour, D, and Moreault, M.

Interdisciplinary collaboration within Quebec community health care centres.

Soc Sci Med. 2000; 55: 991–1003Hudson, B.

Prospects of partnership.

Health Serv J. 1998; 108: 26–27Boon, H, Verhoef, M, O'Hara, D, and Findlay, B.

From parallel practice to integrative health care: a conceptual framework.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2004; 4: 15Boon, H, Verhoef, M, O'Hara, D, Findlay, B, and Majid, N.

Integrative health care: arriving at a working definition.

Altern Ther Health Med. 2004; 10: 48–56Program of Integrative Medicine The University of Arizona.

Program in integrative medicine (homepage on the Internet).

([cited Dec 13 2008]; Available from:)

http://integrativemeidcine.arizona.edu/about/definition.html

Date: 2008Willms, L. and St Pierre-Hansen, N.

Blending in: Is integrative medicine the future of family medicine?.

Can Fam Physician. 2008; 54: 1085–1087Hsiao, A-F, Ryan, G, Hays, R, ID, C, Andersen, R, and Wenger, N.

Variations in provider conceptions of integrative medicine.

Soc Sci Med. 2006; 62: 2973–2987Ramsay, C, Walker, M, and Alexander, J.

Alternative medicine in Canada: use and public attitudes.

Public Policy Sources Number 21.

The Fraser Institute, Vancouver; 1999Park, J.

Use of alternative health care.

Health Reports (Statistics Canada). 2005; 16: 39–42Mior, SA and Laporte, A.

Economic and resource status of the chiropractic profession in Ontario, Canada:

a challenge or an opportunity?.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008; 31: 104–114Agency for Health Policy and Research (AHCPR).

Acute low back pain problems in adults.

Agency for Health Policy and Research, Washington, DC; 1994Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP).

Low back pain evidence review.

Royal College of General Practitioners UK, London; 1998Manniche C, Ankjær-Jensen A, Olsen A, et al.

Low-Back Pain: Frequency, Management and Prevention

from an HTA perspective

Copenhagen: Danish Institute for Health Technology Assessment, 1999.Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care.

Back pain, neck pain, 2000. ; 2000Work Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB).

Chronic pain initiative: report of the chair of the Chronic Pain Panels.

Work Safety and Insurance Board, Ontario; 2000Pasternak, D, Lehnam, J, Smith, H, and Piland, N.

Can medicine and chiropractic practice side-by-side?

Implications for healthcare delivery.

Hosp Top: Res Perspect Healthc. 1990; 77: 8–17Triano, J and Hansen, D.

Chiropractic and quality care, are they exclusive?.

QME Q. 2000; 3: 6–15Weeks J.

The emerging role of alternative medicine in managed care.

Drug Benefit Trends. 1997;9(4):14-6, 25-8.Meeker, W.C.

Public demand and the integration of complementary and alternative medicine in the US

health care system.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000; 23: 123–126Till, G and Till, H.

Integration of chiropractic education into a hospital setting:

a South African experience.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000; 23: 130–133Schneider, J and Gilford, S. Part IV.

The Chiropractor's Role in Pain Management for Oncology Patients

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001 (Jan); 24 (1): 52–57Smith, M, Greene, B, and Meeker, W.

The CAM Movement and the integration of quality health care: the case of chiropractic.

J Ambul Care Manage. 2002; : 1–16Barrett, B.

Alternative, complementary, and conventional medicine: is integration upon us?.

J Altern Complement Med. 2003; 9: 417–427Pelletier, KR, Astin, JA, and Haskell, WL.

Current trends in the integration and reimbursement of complementary and alternative

medicine by managed care organizations (MCOs) and insurance providers:

1998 update and cohort analysis.

Am J Health Promot. 1999; 14: 125–133Astin, J, Marie, A, Pelletier, K, Hansen, E, and Haskell, W.

A review of the incorporation of complementary and alternative medicine

by mainstream physicians.

Arch Intern Med. 1998; 158: 2303–2310Villanueva-Russell, Y.

Evidence-based medicine and its implications for the profession of chiropractic.

Soc Sci Med. 2005; 60: 545–561Breen, A, Carrington, M, Collier, R, and Vogel, S.

Communication between general and manipulative practitioners: a survey.

Complement Ther Med. 2000; 8: 8–14Brussee, W, Assendelft, W, and Breen, A.

Communication between general practitioners and chiropractors.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001; 24: 12–16Mior, SA, Barnsley, J, Boon, H, Ashbury, FD, and Haig, RD.

Designing a model of collaborative health care delivery:

chiropractic services and primary care.

([Submitted for publication])

J Interprof Care. 2009;Strauss, A and Corbin, J.

Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory.

SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks; 1998Patton, MQ.

Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed.

Sage Publications, Newbury Park; 1990Jackson, W.

Methods: doing social research third ed.

Prentice-Hall, Toronto; 2003Poland, B.

Transcription quality.

in: J Gubrium, J Holstein (Eds.)

Handbook of interview research: context and method.

SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks; 2002: 629–650Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine

[homepage on the Internet]. (Minneapolis. [cited 2009 February 13]; Available from:)

http://www.imconsortium.org

Date: 2009Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine Working Group on Education.

Curriculum in integrative medicine: a guide for medical educators.

([cited Feb 27, 2009]; Available from:)

http://www.imconsortium.org/img/assets/20825/CURRICULUM_final.pdf

Date: 2004Mizarchi, N, Shuval, JT, and Gross, S.

Boundary at work: alternative medicine in biomedical settings.

Soc Health Ill. 2005; 27: 20–43Shuval, J and Mizrachi, N.

Changing boundaries: modes of coexistence of alternative and biomedicine.

Qual Health Res. 2004; 14: 675–690Kates N, Craven M.

Family medicine and psychiatry. Opportunities for sharing mental health care.

Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:2561-3, 72-4.

Return to INTEGRATED HEALTH CARE

Since 1-28-2018

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |