Veteran Response to Dosage in Chiropractic Therapy (VERDICT):

Study Protocol of a Pragmatic Randomized Trial

for Chronic Low Back PainThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Pain Medicine 2020 (Dec 12); 21 (Suppl 2): S37–S44

OPEN ACCESS Cynthia R. Long, PhD, Anthony J. Lisi, DC, Robert D. Vining, DC, DHSc, Robert B. Wallace, MD, MSc, Stacie A. Salsbury, PhD, RN, Zacariah K. Shannon, DC, MS, Stephanie Halloran, DC, MS, Amy L. Minkalis, DC, MS, Lance Corber, MSITM, Paul G. Shekelle, MD, PhD Erin E. Krebs, MD, MPH, Thad E. Abrams, MD, MS, Jon D. Lurie, MD, MS, and Christine M. Goertz, DC, PhD

Palmer Center for Chiropractic Research,

Palmer College of Chiropractic,

Davenport, IA, USA.Background: Low back pain is a leading cause of disability in veterans. Chiropractic care is a well-integrated, nonpharmacological therapy in Veterans Affairs health care facilities, where doctors of chiropractic provide therapeutic interventions focused on the management of low back pain and other musculoskeletal conditions. However, important knowledge gaps remain regarding the effectiveness of chiropractic care in terms of the number and frequency of treatment visits needed for optimal outcomes in veterans with low back pain.

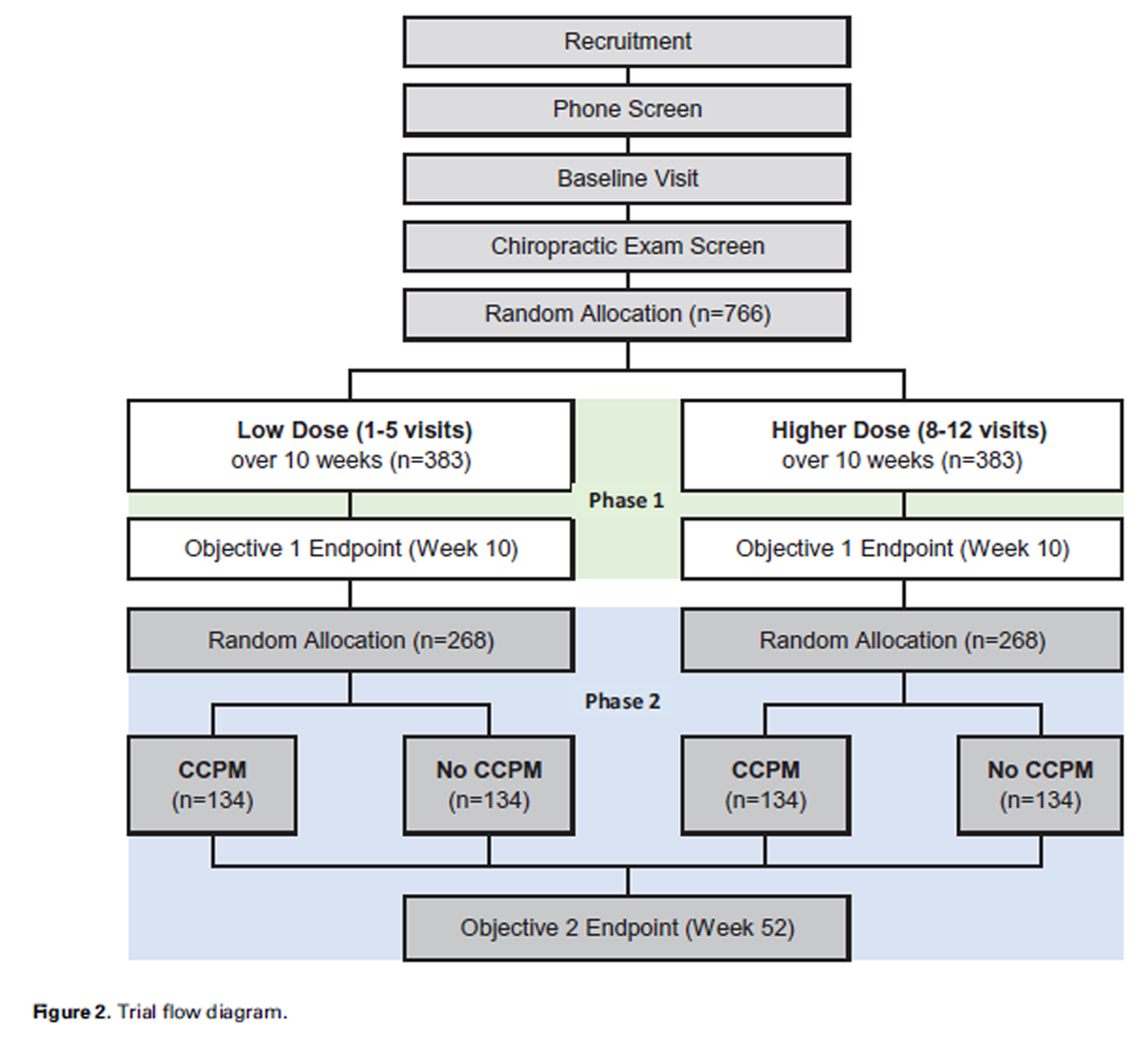

Design: This pragmatic, parallel-group randomized trial at four Veterans Affairs sites will include 766 veterans with chronic low back pain who are randomly allocated to a course of low-dose (one to five visits) or higher-dose (eight to 12 visits) chiropractic care for 10 weeks (Phase 1). After Phase 1, participants within each treatment arm will again be randomly allocated to receive either monthly chiropractic chronic pain management for 10 months or no scheduled chiropractic visits (Phase 2). Assessments will be collected electronically. The Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire will be the primary outcome for Phase 1 at week 10 and Phase 2 at week 52.

Summary: This trial will provide evidence to guide the chiropractic dose in an initial course of care and an extended-care approach for veterans with chronic low back pain. Accurate information on the effectiveness of different dosing regimens of chiropractic care can greatly assist health care facilities, including Veterans Affairs, in modeling the number of doctors of chiropractic that will best meet the needs of patients with chronic low back pain.

Keywords: Chiropractic; Low Back Pain; Nonpharmacologic; Pain Management; Pragmatic Clinical Trial; Veteran.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

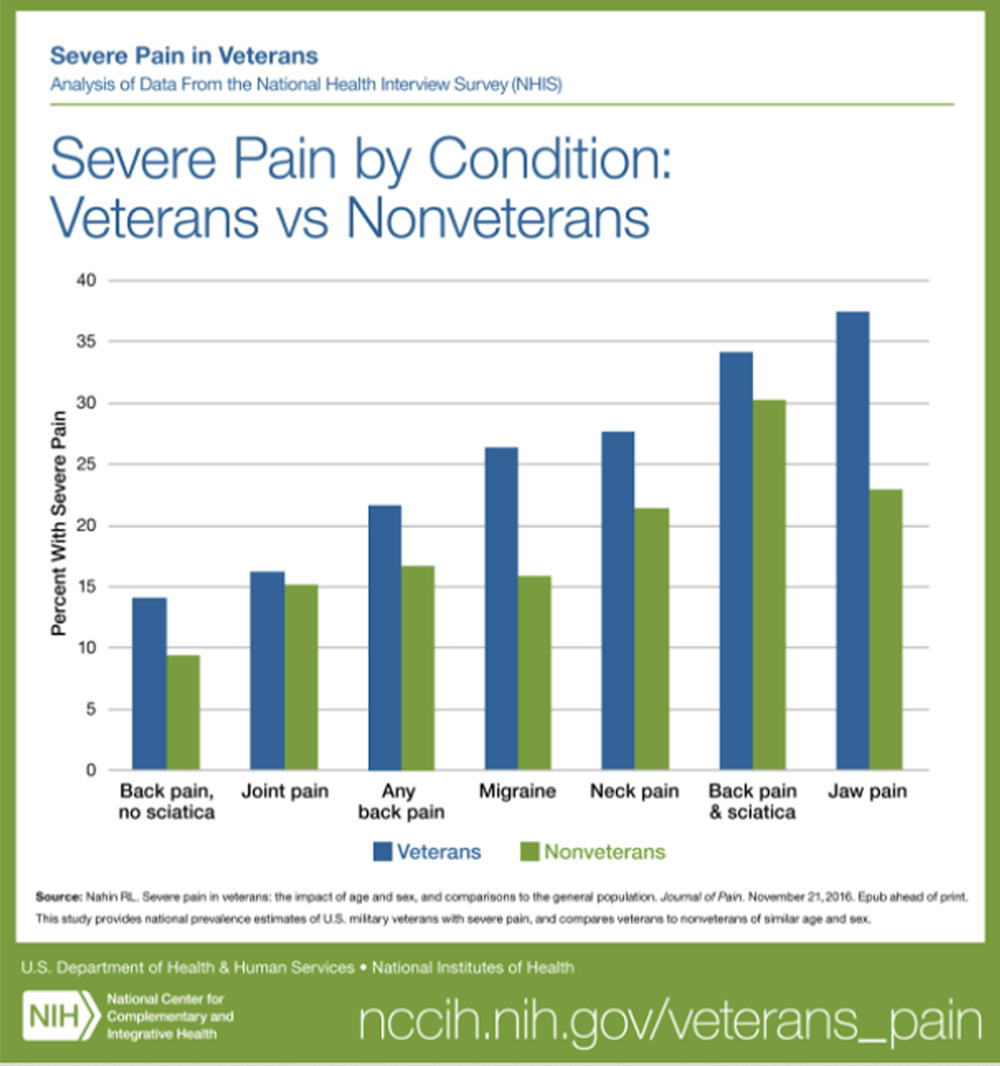

Low back pain (LBP) is the leading global cause of years lived with disability [1], with a point prevalence of 20% in US adults, including 13% with chronic LBP (cLBP). [2, 3] Low back and neck pain were the health conditions responsible for the highest amount of US health care spending in 2016. [4] Most older veterans with pain have a diagnosis of LBP and report pain-related disability, high pain intensity, and the presence of pain on most days of every month. [5] Another study found that at least 50% of veterans receiving care in US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration (VA) facilities were diagnosed with a musculoskeletal condition, and these conditions are increasingly being diagnosed in younger veterans. [6] Veterans diagnosed with pain conditions report high rates of prescription medication use, including opioids, psychotropics, and sleep agents. [7]

The American College of Physicians currently recommends nonpharmacological therapies as first-line treatments for patients with cLBP, several of which are common approaches used by doctors of chiropractic (DCs). [8] DCs are licensed health professionals who provide nonpharmacological, multimodal, conservative care focused on the management of musculoskeletal conditions, most often LBP. [9] DCs are best known for their emphasis on spinal manipulation as a treatment modality, but they routinely provide other manual therapies, recommendations for active interventions, education, and self-management advice. [10]

Chiropractic care is a well-integrated, nonpharmacological therapy in the VA. [10, 11] Since initial implementation in 2004, the VA has expanded its delivery of chiropractic care to 148 facilities. [12] Use of chiropractic care in the VA has been growing at ~ 18% per year, and in Fiscal Year 2019 >300,000 chiropractic visits were provided to >66,000 individual veterans. However, important knowledge gaps remain regarding optimal dose (i.e., the number and frequency of DC visits) for the best outcomes.

The majority of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating spinal manipulation in general, and chiropractic care in particular, for cLBP have focused on short-term effects (two to six weeks) with highly variable treatment schedules in terms of the number of visits. [13] The average annual number of visits by patients to a DC in the private sector varies widely but generally ranges between six and 12. [14] Respondents to a recent Gallup study who had seen a DC within the past year reported an average of 11 visits annually. [15] The only RCT designed to evaluate dose for patients with cLBP found that 12 chiropractic care sessions conveyed the optimum benefit when compared with zero, six, or 18 visits. [16] However, the generalizability of this light-massage-controlled efficacy study to chiropractic practice in real-world settings, especially for veterans, is unknown. In the VA, the mean number of visits per year is five [10], while an integrated care pathway developed by our team using a modified Delphi process recommends eight to 12 visits. [17]

Even less is known about the effectiveness of longerterm care or chiropractic chronic pain management (CCPM; sometimes referred to as “maintenance” or “extended” care) intened to prevent new episodes of LBP and/or to maintain high function. [18] This is an important gap in evidence because the greatest risk factor for experiencing an episode of LBP is history of LBP [19], and between 50% and 70% of those with LBP suffer a recurrence within 12 months. [20, 21] A small cadre of studies on CCPM for patients with cLBP, including two small pilot studies and one RCT of 328 participants, indicate that CCPM may improve outcomes. [22–25] However, these studies did not focus on veterans and were conducted outside the United States.

Methods

Study Objectives

The trial has two primary objectives.Objective 1: Evaluate the effectiveness of a low dose (one to five visits) of chiropractic care compared with a higher dose (eight to 12 visits) in veterans with cLBP at 10 weeks;

Objective 2: Evaluate the effectiveness of CCPM (one scheduled chiropractic visit per month X 10 months) compared with no CCPM following the initial treatment period of 10–weeks at 52 weeks.Overall Design

Figure 1

Table 1 This pragmatic, parallel-group, multisite randomized trial will include 766 veterans with cLBP who are randomly allocated to undergo a course of low- or higher-dose multimodal, evidence-based chiropractic care for 10–weeks (Phase 1). After Phase 1, participants within each treatment arm will again be randomly allocated to receive either CCPM or no CCPM for 10 months (Phase 2).

Figure 1 visually describes the pragmatic nature of the trial. [26] We consider Phases 1 and 2 as separate but linked trials as they each have different interventions, primary outcomes, and random allocations.

Study Population

Veterans 18 years and older reporting cLBP, defined as LBP persisting for three or more months with pain on at least half the days in the past six months [27], will be eligible. The eligibility criteria in Table 1 reflect a largely pragmatic design.

Screening, Recruitment, and Randomization Procedures

Based on our pilot study [28], we anticipate screening 2,000 candidates to accomplish our target enrollment of 766 veterans. We will oversample women, who currently comprise 15.8% of patients seen in the VA chiropractic clinics annually [10], targeting a minimum of 20% female veterans. We will also target veterans with diverse ethnic and racial minority backgrounds at rates proportionate to the veterans seen in our geographically dispersed VA chiropractic clinics.

We will build upon three successfully piloted methods [28] to identify and recruit participants for the trial:1) provider referral, including patients consulted for a first chiropractic visit;

2) invitational letter generated from the VA electronic health record (EHR); and

3) community-based outreach with informational materials.All or a subset of these strategies may be used.

Based on our pilot study [28], we anticipate that the majority of participants will be recruited through provider referral. Veterans who have been consulted to the chiropractic clinic as part of routine care, but not yet seen, will be identified through VA EHR reports. Candidates will be mailed a letter to determine their interest in the study. Study team members will regularly share trial information with VA primary care physicians and other health professionals to promote referrals. Promotional materials created for the community-based outreach strategy will be placed in clinics that commonly refer veterans for chiropractic care and area veteran organizations.

Figure 2 For all recruitment strategies, the site study coordinator will conduct a phone screen to determine initial eligibility (Figure 2). Those who are preliminarily eligible will have a baseline visit scheduled up to 10 days before or on the day of the initial chiropractic visit. At the baseline visit, veterans will provide written informed consent, followed by an eligibility interview to verify participant eligibility status, collection of demographics, and confirmation of contact information. Participants will then complete the baseline assessments in REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA), a secure, HIPAA-compliant, Web-based application. At the initial chiropractic visit, participants will undergo clinical evaluation by a site DC to determine if chiropractic care is indicated and verify that an ICD-10 LBP diagnosis code is consistent with neuromusculoskeletal LBP. Eligibility criteria are listed in Table 1 .

Because all consented participants have been referred to the chiropractic clinic, those found ineligible will receive routine care in the chiropractic clinic, as clinically warranted, but will not be retained in the trial. At the end of the initial chiropractic visit, the study coordinator will randomly allocate eligible participants to one of the two treatment groups in Phase 1 and assist in scheduling visits per group assignment. After participants end Phase 1 by completing the week 10 assessment, the study coordinator will contact them, confirm continued interest in participation in Phase 2, and randomly allocate them to either CCPM or no CCPM. Group allocation for both Phases 1 and 2 will occur through a 1:1 ratio by a predetermined, computergenerated, restricted randomization scheme with random block sizes, stratified by site and sex. A biostatistician independent of the study team will prepare the randomization scheme, which will be stored in the treatment allocation module of REDCap. Future group assignments for both phases are concealed from participants and trial personnel.

Participating Sites

The four participating VA chiropractic clinics are located in Iowa City, Iowa, West Haven, Connecticut, Los Angeles, California, and Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Interventions

Chiropractic care will be provided by licensed DCs who are fully credentialed and privileged by the VA. DCs will have access to an evidence-based clinical decision aid for the treatment of back pain [29] that will serve as an information resource, but have the autonomy to treat patients based on their own clinical judgment, including the development of individualized treatment plans.

Evidenced-based chiropractic interventions include five general categories applied individually depending on diagnosis, patient preferences, and other individual factors. Interventions include1) education to inform patients about their condition and to foster health literacy;

2) passive interventions, such as spinal manipulation and myofascial therapies;

3) transitional interventions, which are monitored or guided by a health professional but performed by a patient during active care, such as therapeutic exercises;

4) active interventions, which are controlled and performed by a patient, such as general exercise and mind–body therapies; and

5) self-management advice designed to help patients self-monitor and self-manage symptoms to reduce the impact of a condition over time. [29]We anticipate that the most common manual therapies will include spinal manipulation. For Phase 2, we anticipate that care during CCPM visits will be similar to care that occurred during Phase 1, although there may be a greater emphasis on active care and self-management.

Participants will have access to the same usual VA medical care available to all veterans during the study. Acupuncture is delivered by some DCs at our four VA sites but is not routinely included as part of chiropractic care in the VA. To maintain our focus on routine chiropractic care, we will ask DCs and participants not to include acupuncture as part of the treatment plan.

Blinding

DCs, site study coordinators, and participants will not be blinded to treatment group assignment. DCs will be blinded to research outcome measures; statisticians will be blinded to treatment group assignment during data analysis; and research personnel conducting computerassisted telephone interviews (CATIs) will be blinded to treatment group.

Baseline and Follow-up Procedures

Participants will complete assessments at the baseline visit and receive e-mail invitations for subsequent followups that include a link to their REDCap forms. If a participant cannot complete the online assessment, research personnel will contact the individual to complete a CATI. In addition, participants will receive weekly text messages asking the number of days in the past week with LBP and the three questions from the Pain, Enjoyment of life, and General activity (PEG) scale for chronic pain.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Table 2 The outcome assessment schedule is shown in Table 2. The primary outcome is the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), the patient self-report one-page modified 24–item version, to assess LBP-related disability. It has documented reliability and validity, ease of use, patient acceptance, and is sensitive to clinical change. [30, 31]

We will administer secondary outcomes that measure other aspects of physical, mental, and social health domains. The PEG is a three-item chronic pain severity tool that includes items assessing average pain intensity, interference with enjoyment of life, and interference with general activity. [32] For the PEG, we have instructed participants to consider their LBP in responding to the questions.

We will use computerized adaptive testing to collect the following Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures [33]: pain interference, physical function, fatigue, sleep disturbance, anger, and satisfaction with social roles and activities.

We will also collect PROMIS domains for neuropathic and nociceptive pain quality, self-efficacy for managing symptoms, and global health. Our REDCap Library will use the Assessment Center Application Programming Interface to calculate domain-specific T-scores, which are normed to a mean of 50 and SD of 10 based on the 2000 US general Census. [33]

The following legacy instruments will measure aspects of mental health. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) will assess depressive disorder. [34] The Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 (GAD-7) will assess generalized anxiety disorder. [35] The PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) will assess PTSD symptoms. [36] The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-10) is a screening questionnaire to determine harmful or hazardous consumption of alcohol, correctly classifying 95% of people as having a clinical diagnosis of an alcohol abuse disorder. [37]

Chronic LBP will be determined by a two-item instrument. [27] A three-item instrument recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will define more general chronic pain. [38]

We will administer the Use of Nonpharmacological and Self-care Approaches (NSCAP), a nine-domain questionnaire developed through the NIH-DOD-VA Pain Management Collaboratory, to assess complementary and integrative health approaches for pain. We will also assess other self-care strategies for LBP care through a questionnaire developed from previous LBP studies. [39, 40]

We will administer Expectations for Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments (EXPECT) at two time points to assess individuals’ expectations of treatment for their cLBP. [41] We modified “complementary and alternative medicine,” phrasing in the instrument to “chiropractic care.”

The Healing Encounters and Attitudes Lists (HEAL), a validated item bank comprised of six patient-centered domains developed through PROMIS methodology [42], will assess nonspecific factors known to influence patient outcomes. We will also collect information to screen for serious adverse events (SAEs) and obtain participant reactions and discomforts.

Statistical MethodsSample Size Determination We first estimated sample size for the two comparisons of interest for Objective 2 at 52weeks: Phase 1 low dose, CCPM vs no CCPM; Phase 1 higher dose, CCPM vs no CCPM. Using the SD of 4.5 (estimated from preliminary data [28]) and a 0.05 level of significance, 107 participants per each of these four groups gives us 90% power to detect a 2.0–point difference [31] between groups on the RMDQ, the primary outcome variable. We then inflated n=107 per group to account for a 20% loss to follow-up in Phase 2 of the study, resulting in 134 participants per each of four groups. Working backwards, we collapsed the four groups into the two groups for Phase 1 (Objective 1: low-dose vs higher-dose chiropractic care) and inflated n=268 (134 X 2) by 30% to account for 20% dropout and 10% of participants choosing not to be randomized into Phase 2, resulting in 383 participants per group, for a total sample size of 766. For Objective 1, assuming 30–40% of the low-dose group will achieve a clinically meaningful improvement on the RMDQ, this sample size provides 90–96% power to detect at least a 15% difference (relative risks = 1.4–1.5) between the low- and higher-dose groups. Figure 2 shows the sample sizes in each phase.

Analytical Methods

Data Analysis Plans Data analysis will use an intention-to-treat approach in which participants will be analyzed according to their assigned treatment groups. All observed data will be used in the analyses. Data analyses will be performed using SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics of demographic and LBP history variables will be presented by group for each site and by group with all sites combined. Descriptive statistics of outcome variables will be presented by group and site over time and by group over time for all sites.

Objective 1 The primary outcome of achieving a clinically meaningful improvement on the RMDQ (≥30% relative to baseline) at week 10 will be modeled with a modified Poisson regression with robust error variance fit through general estimating equations with an unstructured covariance matrix over baseline, week 5, and week 10. We will include terms in the model for these three time points (as a categorical variable), treatment group, and time X treatment group interaction, adjusting for site, sex, age, and baseline LBP intensity. We will report the estimated relative risk of higher-dose vs low-dose chiropractic care at week 10 from this model with 95% confidence intervals.

Objective 2 We will model RMDQ with a linear mixed-effects regression over baseline and weeks 5, 10, 26, 40, and 52. We will include terms in the model for these six time points (as a categorical variable), treatment group, and time X treatment group interaction, adjusting for site, sex, age, and baseline LBP intensity. We will report model-based means and 95% confidence intervals of between-group differences for the two comparisons of interest: Phase 1 low dose, CCPM vs no CCPM, and Phase 1 higher dose, CCPM vs no CCPM at week 52. Secondary outcomes for both Objectives 1 and 2 will be analyzed as continuous variables with linear mixed-effects regression models.Procedures for Handling Missing Data

We will adjust the models for covariates related to missing data. For the analyses of both Objectives 1 and 2, we will conduct sensitivity analyses to examine the possible effects of missing data. We will use multiple imputation methods based on assumptions of missing at random and missing not at random. We will use the tipping point approach for investigating different patterns of missing not at random.

Adverse Event Procedures

Participants will be instructed to notify the site study coordinator if they experience any side effects or adverse events following treatment. For adverse events happening during exam or treatment, the DCs will initiate appropriate clinical protocols and report related information to the study coordinator. We will formally inquire about all adverse events during the assessments according to the schedule in Table 2. We will screen for SAEs with questions about hospitalization, life-threatening disease, and significant change in health status. The study coordinator will follow up with participants responding yes to any of these questions to obtain additional information with standardized questions. All reported adverse events will be reviewed centrally by a clinician on the research team, who will also oversee grading of severity and expectedness.

Implementation and Dissemination Procedures We will report our trial results at key scientific conferences, at national meetings of the VA Health Services Research and Development pain management research community, and to the VA chiropractic field and publish our results in high-impact journals. To inform VA policymakers, we will prepare an executive summary to brief the Deputy Chief Patient Care Services Officer for Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Services and other relevant senior administrators. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, our VA chiropractic clinic sites have not been providing in-person patient care since March 2020. As they begin to resume operation, effects on participant recruitment and intervention delivery may cause the need to make modifications to our protocol.

Discussion

Lack of information on optimal dosing is a significant barrier to planning and operationalizing the continued implementation of VA chiropractic services. Currently, few published data are available to guide the development of DC staffing models that would provide optimal access to care for veterans with cLBP. The extended-care approach of CCPM is not currently used in the VA, in part because of the lack of studies conducted in the United States demonstrating its effectiveness. Accurate information on the effectiveness of different dosing regimens of chiropractic care could greatly assist health systems, including the VA, in modeling the number of DCs that will best meet the needs of patients with cLBP.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is a product of the NIH-DOD-VA Pain Management Collaboratory. For more information about the Collaboratory, visit https://painmanagementcollaboratory. org/.

References:

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence,

and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries

and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.

Lancet 2018;392 (10159):1789–858.Clarke TC, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ.

Use of Complementary Health Approaches for Musculoskeletal

Pain Disorders Among Adults: United States, 2012

Natl Health Stat Rep 2016 (Oct 12); (98): 1–12Shmagel A, Foley R, Ibrahim H.

Epidemiology of Chronic Low Back Pain in US Adults: Data From

the 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016 (Nov); 68 (11): 1688–1694Dieleman JL, Cao J, Chapin A, Chen C, et al.

US Health Care Spending by Payer and Health Condition, 1996-2016

JAMA 2020 (Mar 3); 323 (9): 863–884Reid MC, Guo Z, Towle VR, Kerns RD, Concato J.

Pain-related disability among older male veterans receiving primary care.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57(11):M727–32.Goulet JL, Kerns RD, Bair M, Becker WC, Brennan P, Burgess DJ, et al.

The Musculoskeletal Diagnosis Cohort:

Examining Pain and Pain Care Among Veterans

Pain 2016 (Aug); 157 (8): 1696–1703US House of Representatives.

Between peril and promise: Facing the dangers of VA’s skyrocketing use of

prescription painkillers to treat veterans.

House Committee on Veteran’s Affairs, Subcommittee on Health. 2013. Available at:

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-113hhrg85864/html/CHRG- 113hhrg85864.htm

(accessed February 2017).Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Christensen MG, Hyland JK, Goertz CM, Kollasch MW.

Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2015

Greeley, CO: National Board of Chiropractic Examiners; 2015Lisi AJ, Brandt CA.

Trends in the Use and Characteristics of Chiropractic Services

in the Department of Veterans Affairs

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jun); 39 (5): 381–386Lisi, AJ, Goertz, C, Lawrence, DJ, and Satyanarayana, P.

Characteristics of Veterans Health Administration Chiropractors and Chiropractic Clinics

J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009; 46 (8): 997–1002US Department of Veterans Affairs.

Rehabilitation and prosthetic services: Chiropractic care facility locations. Available at:

https://www.prosthetics.va.gov/chiro/locations.asp

(accessed May 2020).Walker BF, French SD, Grant W, Green S.

Combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;4:CD005427.Goertz CM, Pohlman KA, Vining RV, Brantingham JW, Long CR.

Patient-centered Outcomes of High-velocity, Low-amplitude

Spinal Manipulation for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review

J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012 (Oct); 22 (5): 670–691Gallup, Inc. (2015)

Americans’ Perceptions of Chiropractic

Gallup-Palmer College of Chiropractic Inaugural ReportHaas M, Vavrek D, Peterson D, Polissar N, Neradilek MB.

Dose-response and Efficacy of Spinal Manipulation for Care of Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Randomized Controlled Trial

Spine J. 2014 (Jul 1); 14 (7): 1106–1116Lisi AJ, Salsbury SA, Hawk C, Vining RD, Wallace RB, Branson R, et al.

Chiropractic Integrated Care Pathway for Low Back Pain in Veterans:

Results of a Delphi Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (Feb); 41 (2): 137–148Leboeuf-Yde C, Hestbaek L.

Maintenance Care In Chiropractic—What Do We Know?

Chiropractic & Osteopathy 2008 (May 8); 16: 3Moshe S, Zack O, Finestone AS, et al.

The incidence and worsening of newly diagnosed low back pain in a population of young male military recruits.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17 (1):279.Hancock MJ, Maher CM, Petocz P, et al.

Risk factors for a recurrence of low back pain.

Spine J 2015;15(11):2360–8.Norton G, McDonough CM, Cabral H, Shwartz M, Burgess JF.

Cost-utility of cognitive behavioral therapy for low back pain from the commercial payer perspective.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40(10):725–33.Descarreaux M, Blouin JS, Drolet M, Papadimitriou S, Teasdale N:

Efficacy of Preventive Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Low-Back Pain

and Related Disabilities: A Preliminary Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (Oct); 27 (8): 509–514Senna M.K., Machaly S.A.

Does Maintained Spinal Manipulation Therapy for Chronic Non-specific Low Back Pain

Result in Better Long Term Outcome?

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011 (Aug 15); 36 (18): 1427–1437Eklund, A., I. Jensen, M. Lohela-Karlsson, J. Hagberg, C. Leboeuf-Yde, et al.

The Nordic Maintenance Care Program: Effectiveness of Chiropractic Maintenance Care

Versus Symptom-guided Treatment for Recurrent and Persistent Low Back Pain -

A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial

PLoS One. 2018 (Sep 12); 13 (9): e0203029Eklund A, Hagberg J, Jensen I, et al.

The Nordic Maintenance Care Program: Maintenance Care Reduces the Number of Days

with Pain in Acute Episodes and Increases the Length of Pain Free Periods for

Dysfunctional Patients with Recurrent and Persistent Low Back Pain -

A Secondary Analysis of a Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Tial

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2020 (Apr 21); 28: 19Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M.

The PRECIS-2 tool: Designing trials that are fit for purpose.

BMJ 2015;350:h2147.R.A. Deyo, S.F. Dworkin, D. Amtmann, G. Andersson, et al.,

Report of the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain

Journal of Pain 2014 (Jun); 15 (6): 569–585Long C, Goertz C, Salsbury S, et al.

Single-arm, pragmatic, pilot clinical trial of chiropractic care for U.S. outpatient veterans

with chronic low back pain.

In: Book of Proceedings, 15th World Federation of Chiropractic Biennial Congress

78th European Chiropractors’ Union Convention; 2019 Mar 20–23; Berlin, Germany. p. 97

NOTE: Also registered at ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03254719Vining RD, Shannon ZK, Salsbury SA, Corber L, Minkalis AL, Goertz CM.

Development of a Clinical Decision Aid for Chiropractic Management

of Common Conditions Causing Low Back Pain in Veterans:

Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 677–693Roland M, Fairbank J.

The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire.

Spine 2000;25(24):3115–24.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, Skelly A, Hashimoto R, Weimer M, et al.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an

American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 493–505Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al.

Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale

assessing pain intensity and interference.

J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(6):733–8.Health Measures.

Transforming how health is measured. Available at:

https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php? opt ion=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=190&Ite mid=1214

(accessed May 2020).Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH.

The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population.

J Affect Disord 2009;114(1–3):163–73.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B.

A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7.

Arch Intern Med 2006;166(10):1092–7.Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, et al.

Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans.

Psychol Assess 2016;28(11):1379–91.Babor TF, Biddle-Higgens JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG.

AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care.

Geneva, Switzerland; 2001.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et –al.

Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain

Among Adults - United States, 2016

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 (Sep 14); 67 (36): 1001-1006Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K.

Patient selfmanagement of chronic disease in primary care.

JAMA 2002; 288(19):2469–75.Dannecker EA, Gagnon CM, Jump RL, Brown JL, RobinsonME.

Self-care behaviors formuscle pain.

J Pain 2004;5(9):521–7.Jones SM, Lange J, Turner J, et al.

Development and validation of the EXPECT Questionnaire: Assessing patient expectations

of outcomes of complementary and alternative medicine treatments for chronic pain.

J Altern Complement Med 2016;22 (11):936–46.Greco CM, Yu L, Johnston KL, et al.

Measuring nonspecific factors in treatment: Item banks that assess the

healthcare experience and attitudes from the patient’s perspective.

Qual Life Res 2016;25(7):1625–34.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return NON-PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 6-12-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |