Diagnosis of Sacroiliac Joint Pain: Validity of Individual

Provocation Tests and Composites of TestsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Manual Therapy 2005 (Aug); 10 (3): 207–218 ~ FULL TEXT

Mark Laslett, Charles N. Aprill, Barry McDonald, Sharon B. Young

Department of Health and Society,

Linköpings Universitet,

Linköping, Sweden.

Previous research indicates that physical examination cannot diagnose sacroiliac joint (SIJ) pathology. Earlier studies have not reported sensitivities and specificities of composites of provocation tests known to have acceptable inter-examiner reliability. This study examined the diagnostic power of pain provocation SIJ tests singly and in various combinations, in relation to an accepted criterion standard.

In a blinded criterion-related validity design, 48 patients were examined by physiotherapists using pain provocation SIJ tests and received an injection of local anaesthetic into the SIJ. The tests were evaluated singly and in various combinations (composites) for diagnostic power. All patients with a positive response to diagnostic injection reported pain with at least one SIJ test. Sensitivity and specificity for three or more of six positive SIJ tests were 94% and 78%, respectively. Receiver operator characteristic curves and areas under the curve were constructed for various composites. The greatest area under the curve for any two of the best four tests was 0.842.

In conclusion, composites of provocation SIJ tests are of value in clinical diagnosis of symptomatic SIJ. Three or more out of six tests or any two of four selected tests have the best predictive power in relation to results of intra-articular anaesthetic block injections. When all six provocation tests do not provoke familiar pain, the SIJ can be ruled out as a source of current LBP.

There are more articles like this @ our:

CHIROPRACTIC SUBLUXATION PageKeywords: Sacroiliac joint; Low back pain; Physical examination; Diagnosis; Validity; Sensitivity; Specificity

).

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) can be a nociceptive source of low back pain (Fortin et al., 1994a, b; Bogduk, 1995). SIJ pain has no special distribution or features and is similar to symptoms arising from other lumbosacral structures. There are no provoking or relieving movements or positions that are unique or especially common to SIJ pain (Dreyfuss et al., 1996; Fortin et al., 1994a, b; Schwarzer et al., 1995; Maigne et al., 1996; Fortin and Falco, 1997). The clinical diagnosis of symptomatic SIJ remains problematical, but the ability to make the diagnosis is an important objective. It may be presumed that treatment strategies for SIJ lesions should differ from strategies intended to relieve and treat pathologies of other structures such as disk, nerve root or facet joint pain. Without a readily accessible means of differentiating between these possible sources of pain, treatment strategies are perforce non-specific, and likely to have at best, modest efficacy.

At present, a current acceptable method of confirming or excluding the diagnosis of a symptomatic SIJ is fluoroscopically guided, contrast enhanced intra-articular anaesthetic block (Fortin et al., 1994b; Grieve, 1988; Merskey and Bogduk, 1994; Schwarzer et al., 1995; Sakamoto et al., 2001; Adams et al., 2002). While certain SIJ tests have been shown to have acceptable inter-rater reliability (Laslett and Williams, 1994; Kokmeyer et al., 2002), current evidence suggests that these tests alone cannot predict the results of a criterion standard such as diagnostic injection (Dreyfuss et al., 1996; Maigne et al., 1996; Slipman et al., 1998). These reports have not reported the sensitivity, specificity or likelihood ratios or provided data on the diagnostic power of individual or composites of provocation SIJ tests (Slipman et al., 1998). However, in a previous publication, the current authors have identified a composite of three provocation SIJ tests in the absence of centralization during repeated movement testing has clinically useful sensitivity, specificity and positive likelihood ratio (93%, 89% and 6.97%, respectively) (Laslett et al., 2003).+

Conceptually, it seems reasonable to propose that stress testing of the SIJ should provoke pain of SIJ origin. However, clinical stress tests are unlikely to load the targeted structure alone. Herein lies the problem. When a test provokes familiar pain, the question arises if this is evidence of pathology within the targeted structure, or evidence of pathology in a different but nearby structure that is also stressed at the same time. However, if different stress tests of a structure provoke pain, greater diagnostic confidence may result. The use of composites of tests is common in musculoskeletal medicine. When a straight leg raise test provokes familiar leg pain, nerve root irritation from a herniated lumbar disc may be suspected. However, pain, paraesthesiae or skin anaesthesiae in a known segmental distribution, weakness of key muscles or reflexes must also be present before the diagnosis of a herniated lumbar disc can be made with any degree of confidence. Confirmation with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging completes the composite of tests for this diagnosis. The need for diagnostic research to investigate the added value of composites of tests within the diagnostic process has been emphasized (Deville et al., 2000; Grieve, 1988). This current study explored the utility of utilizing composites of SIJ provocation tests to predict the results of fluoroscopically guided, contrast enhanced SIJ blocks (diagnostic injection

Material and methods

The diagnosis of symptomatic SIJ pathology may mean that either SIJ structures contain the pain generating tissues, or that the SIJ functions or malfunctions in such a way as to cause pain. Throughout this report, references to symptomatic SIJ, SIJ pain or pathology are confined to meaning that the pain originates from the SIJ structures.

The study design is presented graphically in Fig. 1. Physiotherapists (ML and SBY) visited a private radiology practice in New Orleans specializing in the diagnosis of spinal pain at regular intervals between January 1997 and August 1998 to carry out the clinical evaluations. Patients were not consecutive. Patients deemed likely by clinic staff to have SIJ pain were scheduled to receive the SIJ provocation tests on a day when an examining physiotherapist visited the clinic. The clinical examination and injection procedures were completed the same day. No other treatment was provided by the physiotherapist. The physiotherapists were blinded to the results of previous diagnostic injections and the results of previous imaging studies. Diagnostic injection was conducted blind from the results of SIJ provocation tests and the results of the physiotherapy examination. Results from the clinical and SIJ injection procedures were recorded on separate standardized data collection forms. Informed consent was sought prior to the clinical evaluations.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with buttock pain, with or without lumbar or lower extremity symptoms were invited to participate in the study. Patients were scheduled for the clinical evaluation in an opportunistic fashion with some patients being examined by the physical therapist at their initial visit to the clinic and others scheduled to return on a day when the physical therapist was present. Each patient had undergone imaging studies and had a variety of unsuccessful therapeutic interventions. They were referred for diagnostic evaluation and procedures by a variety of medical and allied health practitioners and a few were self-referred. Patients were drawn from the New Orleans metropolitan area, with some intrastate and interstate referrals.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the study if they were unwilling to participate, had only midline or symmetrical pain above the level of L5, had clear signs of nerve root compression (complete motor or sensory deficit), or were referred for specific procedures excluding SIJ injection. Those deemed too frail to tolerate a full physical examination, were also excluded.

Background data collection

Patient data recorded included age, gender, occupation, employment status, pending litigation, duration of symptoms, aggravating/relieving factors and cause of current episode. The patient completed detailed pain drawings (Ohnmeiss et al., 1999; Beattie et al., 2000) and pain intensity was measured on a verbal analogue scale (VAS) (0 = "no pain" and 10 = "worst imaginable pain"). Disability was estimated with the Roland–Morris questionnaire (Roland and Morris, 1983; Jensen et al., 1992) and the Dallas Pain and Disability questionnaire (Lawlis et al., 1989).

Operational definitionsThe familiar symptom: The familiar symptom is the pain or other symptoms (such as aching, burning, paraesthesiae or numbness) identified on a pain drawing, verified by the patient as being the complaint that has led the patient to seek diagnosis and treatment. During a diagnostic test the familiar symptoms must be distinguished from other symptoms produced by the test, and may be produced, increased, decreased or abolished.

Choice of SIJ tests to evaluate: Tests based on palpation for positional faults or movement dysfunctions were not considered for inclusion in the current study, since adequate inter-examiner reliability has not been demonstrated in earlier studies (Potter and Rothstein, 1985; McCombe et al., 1989; Meijne et al., 1999). However, one study found that a selection of pain provocation tests were found to have acceptable reliability (Cohen’s Kappa 40.04) (Laslett and Williams, 1994) and these were considered as suitable procedures for evaluation of diagnostic validity.

Positive provocation SIJ test: A provocation SIJ test that produces or increases familiar symptoms. Negative provocation SIJ test: A provocation SIJ test that does not produce or increase familiar symptoms.

Positive SIJ injection: Slow injection of solutions provokes familiar pain, and instillation of a small volume of local anaesthetic (less than 1.5 cc) resulted in 80% or more relief of the pain for duration of effect of the anaesthetic agent. Anaesthetic effect was assessed by change in pre- and post-injection numeric pain rating scales. Patients reporting a concordant pain response and at least 80% relief of their familiar pain were scheduled for a confirmatory block. Lidocaine was used in the initial injection and Bupivicaine was used in the confirmatory block to eliminate the need for a sham injection (Barnsley et al., 1993).

Negative SIJ injection: Diagnostic injections were considered indeterminate when there was a concordant pain response but insufficient pain relief, or when substantial pain relief was reported in the absence of provocation of familiar pain. Indeterminate responses were considered negative for statistical analysis. Injections not causing concordant pain provocation or analgesic response were deemed negative.

Clinical evaluation

Figure 2

Figure 3

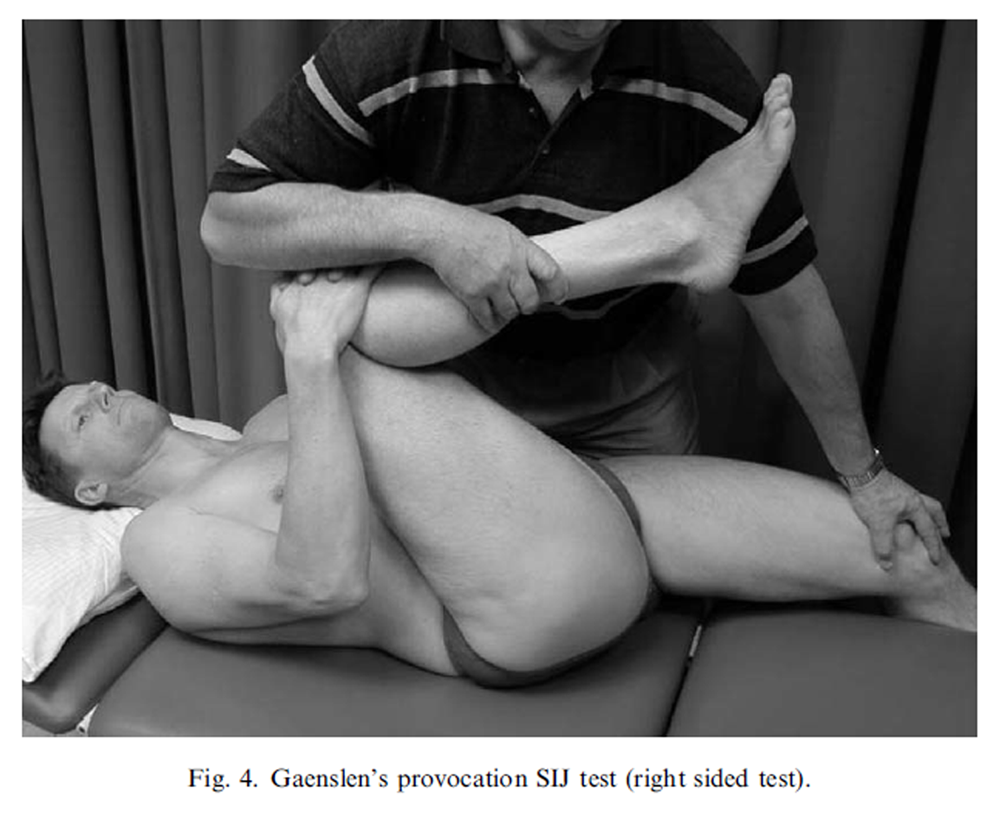

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

The clinical evaluation was carried out by physiotherapists with 25 years (ML) and 17 years (SBY) experience in orthopaedic examinations of spinal pain patients and included a standard history and structured physical examination lasting between 30 min and 1 h. The structured physical examination included aMcKenzie examination of the lumbar spine (McKenzie, 1981), SIJ provocation tests (Laslett and Williams, 1994), and a hip joint assessment (Cyriax, 1975).

The sacroiliac pain provocation tests: The tests employed in this study were: distraction (Figure 2), right sided thigh thrust (Figure 3), right sided Gaenslen’s test (Figure 4), compression (Figure 5) and sacral thrust (Figure 6) and have acceptable inter-rater reliability (Kokmeyer et al., 2002) and have been described previously (Cyriax, 1975; Laslett and Williams, 1994; Maigne et al., 1996; Laslett et al., 2003).

Radiology examination

The technique used for fluoroscopically guided contrast enhanced SIJ arthrography has been previously described (Fortin et al., 1994b; Schwarzer et al., 1995). The radiologist examiner (CA) has over 20 years experience in diagnostic spinal injection procedures, including SIJ injection. The SIJ injection was given within 30 min of completion of the physiotherapy clinical examination. Pain drawings and numeric pain rating scales for pain intensity were acquired prior to and 30–60 min following diagnostic injection.

During this study, corticosteroid was introduced into the joint as a therapeutic procedure when the initial injection of contrast and Lidocaine provoked familiar symptoms, as was normal practice at the clinic. The radiologist documented the procedure(s) performed, radiographic findings and conclusions. Pain provocation and analgesic responses to SIJ injection were recorded.

Data reduction and analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using statistical software Minitab (version 13.31 Minitab Inc. r2000), and CIA (version 2.0.4 r Trevor N Bryant, 2000 University of Southhampton) (Bryant, 2000). Two by two contingency tables were constructed and sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and likelihood ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each test independently and for composites of SIJ tests. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values have been calculated using the Wilson method (Altman et al., 2000; Bryant, 2000). Likelihood ratios have been calculated using the score method (Altman et al., 2000). Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves are an overall measure of diagnostic efficacy (Altman et al., 2000, pp. 111–116). These curves combine sensitivity and specificity, and the area under the curve (AUC) is a summary measure of achieved discrimination, with perfect discrimination represented by an AUC of 1.0, and scores equal to or less than 0.5 are equivalent to or worse than can expected by random chance. The closer the AUC approaches 1.0, the better discriminatory power the diagnostic test has in relation to the criterion or reference standard.

Results

Sixty-two patients agreed to participate and were examined by both radiologist and physical therapist. Of these patients, three were unable to tolerate the physical examination, two were pain free on the day of the clinical assessment, seven had no SIJ injection, and two had a bony obstruction causing a technical failure to inject the SIJ. These patients were excluded from the study. Forty-eight patients satisfied all inclusion criteria. Twenty-seven patients received the clinical assessment at their first clinic visit, 21 patients at the second.

There were no significant differences between positive and negative responders to diagnostic injection with regards to age, gender, working status, Dallas and Roland questionnaire results or pain intensity prior to examination. Table 1 presents basic demographic, and disability data for all included patients.

Of the 48 patients satisfying inclusion criteria 16 patients had positive SIJ injections. There were no adverse effects reported by patients from either the physical examination or SIJ injection, other than temporary local soreness at the injection site or increase in discomfort from the clinical examination.

The provocation SIJ tests provoked familiar pain in those patients confirmed by diagnostic injection as having painful SIJ pathology more commonly than those with negative injections. However, false positive tests were common. Prevalence of positive tests in the sample ranged from 29.2% to 50.0%. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios for each individual test are presented in Table 2.

One approach to combining tests is simply to count the number of positives. Two by two contingency tables for the results of composites of all six SIJ tests (0, 1 or more, 2 or more and so on) versus the results of diagnostic injection and are presented in Table 3. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios were calculated and are presented in Table 4. The optimum composite rule was to identify the SIJ as the pain generator if there were three or more positive tests, with estimated sensitivity of 93.8%, specificity of 78.1%, and AUC of 0.842 (s.e. 0.042).

On the other hand, looking at specific combinations of tests, it was found that the distraction test had the highest single positive predictive value (PPV) and AUC, the thigh thrust, compression and sacral thrust tests improved the overall diagnostic ability (as measured by improvement in AUC). The Gaenslen’s tests did not improve the AUC value. This implies that Gaenslen’s tests did not contribute positively and may be omitted from the diagnostic process without compromising diagnostic confidence. The optimal rule was to perform the distraction, thigh thrust, compression and sacral thrust tests but stopping when there are two positives.

This resulted in an AUC of (0.819, s.e. 0.054) with sensitivity of 0.88 and specificity of 0.78. Table 5 presents two by two contingency tables for the four tests that positively contribute to making the diagnosis (distraction, thigh thrust, compression and sacral thrust). Table 6 presents sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios for two positives of these four tests.

Discussion

All patients with SIJ pathology identified by injection had at least one positive test. Only one patient out of 16 with SIJ pain had a single positive test with 15 having two or more positive SIJ tests. Consequently, one reasonable clinical rule is that when all provocation SIJ tests are negative, symptomatic SIJ pathology can be ruled out. The thigh thrust test is the most sensitive test and the distraction test is most specific.

Figure 7 Three or more of the six tests produce the highest likelihood ratio (4.29), but removal of Gaenslen’s test from the examination and application of the rule "any two positive tests" of the remaining four tests produces almost as good a result (likelihood ratio = 4.0). Because the thigh thrust and distraction tests have the highest individual sensitivity and specificity, respectively (see Table 3), performance of these tests first seems reasonable. If both tests provoke familiar pain, no further testing is indicated. If one test is positive, the compression test is applied and if positive, a painful SIJ is likely and no further testing is required. If compression is not painful the sacral thrust test is applied. If this is painful, SIJ pathology is likely, whereas if it is not painful, SIJ pain is unlikely. Not only does this rule avoid subjecting patients to unnecessary tests, but also would in most cases permit a diagnosis even if one or more tests were not completed. Figure 7 presents a diagnostic algorithm for this reasoning process.

When severe pain occurs with all body movements (e.g. acute disc prolapse, fractures, etc.), pain is provoked by any test including the provocation SIJ tests. In these circumstances interpretation of the SIJ tests is inappropriate. In our opinion, where another source of pain is known to be a major source of pain, the interpretation of the SIJ tests as evidence of a symptomatic SIJ should be avoided or entertained only with scepticism.

No single study can satisfy all criteria recommended by advisory groups (Deyo et al., 1994) and this study is no exception. One threat to external validity within this study is that the patients in this study were more chronic and disabled than those usually seen in primary care or most secondary referral environments. While generalizability of the study results must be questioned, it is our anecdotal experience that most primary care and secondary referral patient populations are less difficult to examine and analyse, and these results understate rather than overstate the diagnostic power of the provocation SIJ tests. Additionally, the effects of preceding provocation tests may confound interpretation of single test results. Progressive increases or decreases in pain responses to the second, third or fourth tests cannot be ruled out as a confounding factor. A different study design would be required to eliminate this confounder, such as allowing a specified rest period between tests, or applying only a single test to each individual patient before the diagnostic injection. However, the latter design would not permit evaluation of groups or sequences of tests.

The criterion standard for the diagnosis of painful lumbar facet joint is comparative anaesthetic or placebo controlled blocks and this is widely accepted and utilized in studies (Dreyfuss et al., 2003). However, standards used in recent studies of SIJ pain diagnosis are diverse. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) has proposed criteria for making the diagnosis of symptomatic SIJ and are:(1) pain is present in the region of the SIJ,

(2) stressing the SIJ by clinical tests that are selective for the joint reproduces the patient’s pain,

(3) selectively infiltrating the putatively symptomatic joint with local anaesthetic

completely relieves the patient of pain (Merskey and Bogduk, 1994).In recent diagnostic studies of SIJ pain there are variations on a general theme. Fortin et al. (1994a) used patterns of pain distribution, provocation of pain during SIJ injection and a single anaesthetic block. Schwarzer et al. (1995) used a single injection in patients with pain ‘centred’ below L5/S1 and a 75% reduction in pain following injection of local anaesthetic. Dreyfuss et al. (1996) used a single injection of local anesthetic and cortico-steroid, noted pain provocation and required more than 90% reduction in the ‘main pain’ as distinct from a change in VAS assessment of pain generally. Maigne et al. (1996) used comparative double blocks in patients selected by pain drawing as likely to have SIJ pain and at least 75% reduction on a general pain VAS. Slipman et al. (1998) used an 80% reduction on a general pain VAS following single anaesthetic injection in consecutive LBPpa tients. In an earlier presentation of a subset of patients from the current study, we utilized double comparative blocks and 80% or more reduction in a verbal analogue scale of pain intensity and provocation of pain during SIJ injection as the criterion standard (Laslett et al., 2003).

In the current analysis, a single diagnostic injection under fluoroscopic control and contrast enhancement that provoked familiar pain was used and resulted in 80% or more relief of pain as measured by a verbal analogue scale of pain intensity. Where familiar pain was provoked during injection, corticosteroid was injected in addition to local anaesthetic and the patient scheduled for a confirmatory, comparative block. It is noted that in a recent publication (Bogduk and McGuirk, 2002, p. 174), double comparative blocks are recommended for confirmation of the diagnosis. The data collection for the current paper was between 1996 and 1998, at the time when mixtures of standards were common. Future criterion standard validity studies should use the standard recommended by Bogduk and McGuirk without inclusion of corticosteroid in the initial screening injection.

Although false positive rates for SIJ injections have not been previously reported, a rate of 7.7% may be calculated from data presented from one study (Schwarzer et al., 1995) and 20.5% from another (Maigne et al., 1996). In this current analysis, the 16 patients reporting a positive response to a single anaesthetic injection and 12 proceeded on to receive a second injection. All of these patients reported a positive anaesthetic response, confirming the diagnosis of SIJ pathology with a false positive rate of zero. Of the four initial responders who did not receive a confirmatory block, three derived such pain relief from the initial block that a confirmatory block was inappropriate. It is assumed that ablation of pain following the initial block was a consequence of the introduction of corticosteroid during the initial procedure. One patient did not return for the scheduled confirmatory block for unknown reasons.

In a worst-case scenario using the comparative confirmatory blocks as a criterion standard, we can propose that all four cases not returning for a confirmatory block would have returned a negative response to that procedure and the initial block deemed false positive. Estimations (with 95% confidence intervals) for sensitivity, specificity, positive/negative predictive values would be 83.3 (55.2, 95.3), 69.4 (53.1, 82.0), 47.6 (28.3, 67.7), 92.6 (76.6, 97.9) percent, respectively, and positive/negative likelihood ratios would be 2.72 (1.57, 4.74) and 0.24 (0.66, 0.87), respectively. The estimations from this scenario still exceed what can be expected by random chance at the lower 95% confidence limit. However, in this scenario the false positive rate (95% confidence intervals) would have been 30.6% (15.1, 45.6).

Although diagnostic injection is the only available criterion standard against which clinical tests can reasonably be evaluated for validity, it is acknowledged that false negative and false positive responses to injection are possible. Where there is a defect in the articular capsule, leakage of anaesthetic into adjacent areas may occur (Fortin et al., 1994a; Schwarzer et al., 1995), and pain relief may be a reflection of an anaesthetic affect of these structures rather than the SIJ structures. This possibility and the unknown effect of psychosocial influences on pain responses to invasive diagnostic procedures may contribute to the false positive and negative rates. No attempt to estimate these influences was attempted during this study. In addition, intra-articular injection of anaesthetic has the potential to ablate SIJ pain when originating within the joint cavity, but is unlikely to have an anaesthetic effect on SIJ structures external to the joint (Grieve, 1988). (Maigne et al., 1996; Laslett et al., 2003) Where SIJ structures external to the joint cavity are actual pain generators, an intra-articular injection of local anaesthetic into and confined to the joint space will produce a false negative diagnostic result, whereas the clinical examination may possibly correctly identify the periarticular and unanaesthetized SIJ structures as pain generators.

The patients entered into this study were not consecutive. The physiotherapists performing the clinical examination were not residents in New Orleans where the diagnostic injections were being carried out and could visit only intermittently over a 19-month period. Consequently, no estimate of prevalence should be inferred from the data presented in this report. Additionally, calculation of predictive values or false positive rates in a sample, at least partially selected for possible SIJ involvement, are not be generalizable to other patient populations.

The results of this study are in contrast to the results of earlier similar studies (Schwarzer et al., 1995; Dreyfuss et al., 1996; Maigne et al., 1996; Slipman et al., 1998), and the conclusion from a meta-analysis of studies of clinical tests for painful SIJs (van der Wurff et al., 2000). However, there is support for the use of pain provocation tests in SIJ diagnosis (Laslett et al., 2003) and these tests are preferred over palpation tests for mobility or position (Freburger and Riddle, 2001). It is difficult to account for the differences between our results and the results from other studies. However, some of the explanation may lie in differences in application of the examination technique. There is evidence that physiotherapists apply different degrees of force when utilizing SIJ provocation tests (Levin et al., 1998, 2001) and this may be one of several factors influencing results.

Conclusion

Provocation SIJ tests have significant diagnostic utility. Six provocation tests were selected on the basis of previously demonstrated acceptable inter-examiner reliability. Two of four positive tests (distraction, compression, thigh thrust or sacral thrust) or three or more of the full set of six tests are the best predictors of a positive intra-articular SIJ block. When all six SIJ provocation tests are negative, painful SIJ pathology may be ruled out.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Duncan Reid, Wayne Hing, and the Auckland University of Technology Multimedia Unit for assistance with photographs.

Travel and Louisiana licensing costs for Mrs. Young were funded by The McKenzie Institute International.

REFERENCES:

Adams MA, Bogduk N, Dolan P.

Biomechanics of low back pain.

London: Churchill-Livingstone; 2002.Altman DG, Machin D, Bryant TN, Gardner MJ.

Statistics with confidence. 2nd ed.

Bristol: British Medical Journal; 2000.Barnsley L, Lord S, Bogduk N.

Comparative local anaesthetic blocks in the diagnosis of cervical zygapophysial joint pain.

Pain 1993:99–106.Beattie PF, Meyers SP, Stratford P, Millard RW, Hollenberg GM.

Associations between patient report of symptoms and anatomic impairment

visible on magnetic resonance imaging.

Spine 2000; 25(7):819–28.Bogduk N.

The anatomical basis for spinal pain syndromes.

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 1995;18(9):603–5.Bogduk N, McGuirk B.

Medical management of acute and chronic low back pain, vol. 13.

Amsterdam: Elsevier Science BV; 2002.Bryant TN.

Confidence interval analysis for windows. (2.0.0):

BMJ Books, 2000.Cyriax, J., 6th ed.

Textbook of orthopaedic medicine. Volume one:

diagnosis of soft tissue lesions.

London: Balliere Tindall; 1975. p. 546–54.Deville WLJM, van der Windt DAWM, Dzaferagic A, Bezemer PD, Bouter LM.

The test of lasegue: systematic review of the accuracy in diagnosing herniated discs.

Spine 2000;25(9):1140–7.Deyo RA, Haselkorn J, Hoffman R, Kent DL.

Designing studies of diagnostic tests for low back pain or radiculopathy.

Spine 1994;19(18 (Suppl)):2057S–65S.Dreyfuss PH, Michaelsen M, Pauza K, McLarty J, Bogduk N.

The value of history and physical examination in diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain.

Spine 1996(21):2594–602.Dreyfuss PH, Dreyer SJ, Vaccaro A.

Lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint injections.

The Spine Journal 2003;3(Suppl):50–9.Fortin JD, Falco FJ.

The Fortin finger test: an indicator of sacroiliac pain [see comments].

American Journal of Orthopedics 1997;26(7):477–80.Fortin JD, Aprill C, Pontieux RT, Pier J.

Sacroiliac joint: pain referral maps upon applying a new

injection/arthrography technique. Part II: clinical evaluation.

Spine 1994;19(13):1483–9.Fortin JD, Dwyer AP, West S, Pier J.

Sacroiliac joint: pain referral maps upon applying a new

injection/arthrography technique. Part 1: asymptomatic volunteers.

Spine 1994;19:1475–82.Freburger JK, Riddle DL.

Using published evidence to guide the examination of the sacroiliac joint region.

Physical Therapy 2001;81(5):1135–42.Grieve GP.

Diagnosis.

Physiotherapy Practice 1988;4:73–7.Jensen MP, Strom SE, Turner JA, Romano JM.

Validity of the sickness impact profile Roland scale as a

measure of dysfunction in chronic pain patients.

Pain 1992;50:157–62.Kokmeyer DJ, van der Wurff P, Aufdemkampe G, Fickenscher TCM.

The reliability of multitest regimens with sacroiliac pain provocation tests.

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 2002;25(1):42–8.Laslett M, Williams M.

The reliability of selected pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint pathology.

Spine 1994;19(11):1243–9.Laslett M, Young SB, Aprill CN, McDonald B.

Diagnosing painful sacroiliac joints: a validity study of a

McKenzie evaluation and sacroiliac joint provocation tests.

Australian Journal of Physiotherapy 2003;49:89–97.Lawlis GF, Cuencas R, Selby D, McCoy CE.

The development of the Dallas pain questionnaire.

An assessment of the impact of spinal pain on behavior.

Spine 1989;14(5):511–6.Levin U, Nilsson-Wikmar L, Stenstrom CH, Lundeberg T.

Reproducibility of manual pressure force on provocation of the sacroiliac joint.

Physiotherapy Research International 1998;3(1): 1–14.Levin U, Nilsson-Wikmar L, Harms-Ringdahl K, Stenstrom CH.

Variability of forces applied by experienced physiotherapists

during provocation of the sacroiliac joint.

Clinical Biomechanics 2001; 16:300–6.Maigne JY, Aivaliklis A, Pfefer F.

Results of sacroiliac joint double block and value of

sacroiliac pain provocation tests in 54 patients with low back pain.

Spine 1996;21(16):1889–92.McCombe PF, Fairbank JCT, Cockersole BC, Pynsent PB.

Reproducibility of physical signs in low back pain.

Spine 1989;14(9): 908–18.McKenzie RA.

The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy.

Waikanae: Spinal Publications Ltd.; 1981.Meijne W, van Neerbos K, Aufdemkampe G, van der Wurff P.

Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability of the Gillet test.

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 1999; 22(1):4–9.Merskey H, Bogduk N.

Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic

pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. 2nd ed.

Seattle: IASPP ress; 1994.Ohnmeiss DD, Vanharanta H, Ekholm J.

Relationship of pain drawings to invasive tests assessing intervertebral disc pathology.

European Spine Journal 1999;8(2):126–31.Potter NA, Rothstein JM.

Intertester reliability for selected clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint.

Physical Therapy 1985;65(11): 1671–5.Roland M, Morris R.

A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I:

development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain.

Spine 1983;8(2):141–50.Sakamoto N, Yamashita T, Takebayashi T, Sekine M, Ishii S.

An electrophysiologic study of mechanoreceptors in the sacroiliac joint and adjacent tissues.

Spine 2001;26:E468–71.Schwarzer AC, Aprill C, Bogduk N.

The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain.

Spine 95;20(1):31–7.Slipman CW, Sterenfeld EB, Chou LH, Herzog R, Vresilovic E.

The predictive value of provocative sacroiliac joint stress

maneuvers in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome.

Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1998;79(3):288–92.van der Wurff P, Meyne W, Hagmeijer RHM.

Clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint:

a systematic methodological review. Part 2: validity.

Manual Therapy 2000;5(2):89–96.

Return to SPINAL PALPATION

Return to LOCATING SUBLUXATIONS

Since 12-04-2021

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |