DD Palmer and the Egyptian Connection:

A Short ReportThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Asia-Pacific Chiropractic Journal 2024; 5 (1) ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Phillip Ebrall, BAppSc (Chiropr), PhD

Editor, Asia-Pacific Chiropractic Journal

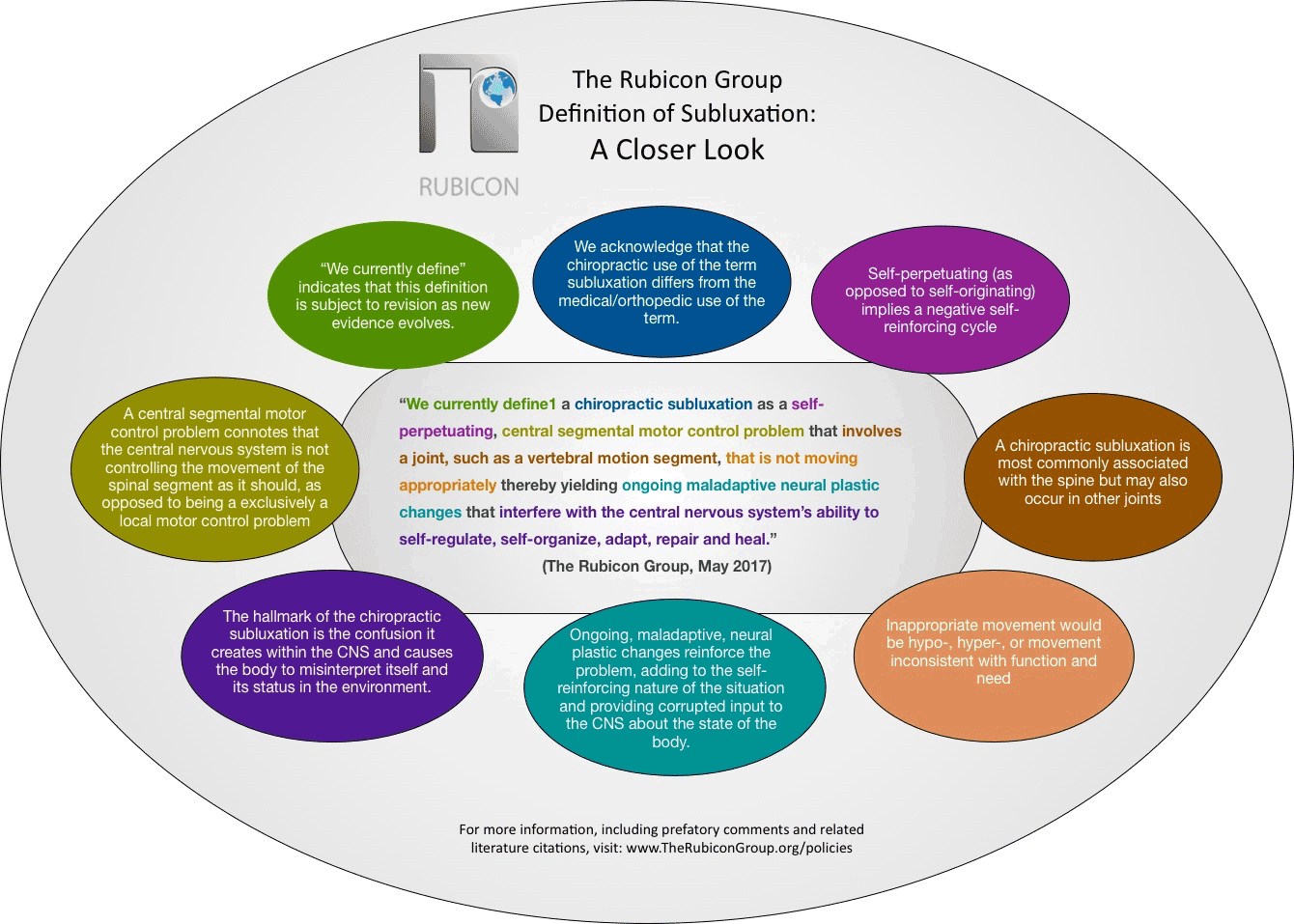

This paper describes the first known description of the ‘idea of subluxation’ as a small dysfunction in the spine which affected a person’s health and function. The authoritative source document is the Edwin Smith Manuscript, introduced to the world in the 1920s. This paper reports this interpretation of Egyptian medical writings dating from 1,600 BC and earlier, in which small spinal dysfunctions were noted and clinically managed.

Indexing Terms: Subluxation, Edwin Smith, chiropractic, Egyptian medical writings

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

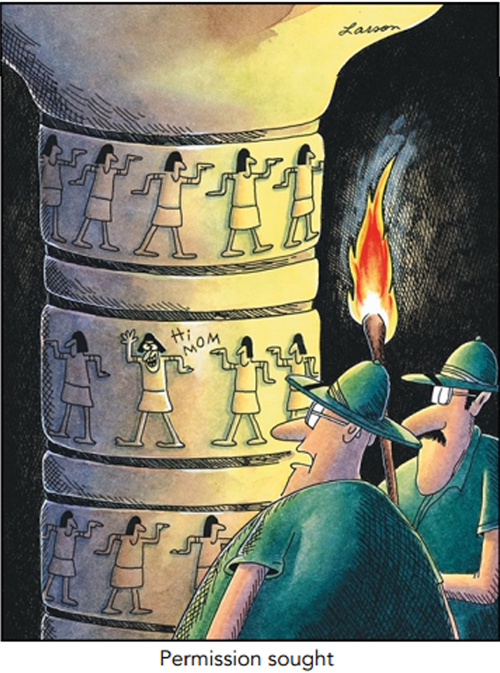

Figure 1 Clues to the antiquity of the idea that DD Palmer codified as ‘subluxated vertebrae modulating tone’ came as early as 1905 [1] when he referred to ‘Chinese and Egyptian history … system of healing … Manual Therapeutics.’ (Figure 1)

Palmer alluded to this history [2] in his 1906 text co-written with his son, BJ Palmer but was clear in his 1910 tome,

on p. 12, [3] where he wrote:‘Dr. Atkinson [4–6] has frequently informed me that the replacing of displaced vertebrae for the relief of human ills had been known and practiced by the ancient Egyptians for at least 3000 years.’

and on p. 13:

‘many of the methods employed in ancient Greece and older Egypt are being restored’

In 1914 Palmer wrote: [7, p. 8]

‘The principles which form chiropractic science have always existed; and are now being revealed to the world by D. D. Palmer’

Palmer could not be more clear that the idea of small dysfunction in the spine, between vertebrae, had long been associated with altered health status. Care must be taken to not claim that these historical instances of this ‘idea’ represent ‘subluxation’ as it is understand today; yet it may turn out to be so should a scholar with appropriate knowledge investigated it further. Nevertheless, the contemporary claim that ‘subluxation may be taught only in an historical context’ [8] is shown to be shallow as at no point do those who make that claim offer any evidence of the depth and breadth of that history.

While it is true that subluxation as understood today is more complex, the original description, sprain, wrenching , incomplete luxation or dislocation, is represented in the Edwin Smith papyrus. Subluxation has its historical origins and the original meaning is still included in the modern term.

Chiropractic’s Indiana Jones, Dr Gary Bovine, has shown that subluxation came into renaissance language as Latin. [9] A point of relevance here is that Bovine has traced the idea back to the Greek medical writings, largely attributed to, or collected under the name of, Hippocrates. [10]

Bovine has reported that the idea of subluxation was known in the 10th Century [11] and it is well known that Johannes Hieronymi wrote the first medical doctoral thesis on the topic in 1746. [12] Bovine demonstrated that the Greek word parathréma led to the Latin term subluxationibus, written by Hieronymi in 1746. SVBLVXATIONIBVS relies on the transliteration of pararthrema. Bovine [11] states:‘in 1532 the Italian translator Giovanni Bernardo Feliciano created the words subluxatio, subluxantur, subluxationibus to have a suitable substitute for the Greek word pararthrema’

The question that must be answered is, what did the Greeks mean when they spoke of pararthrema? The answer that is found in the Egyptian medical literature is that they were speaking of a spinal sprain of sufficient impact on the individual to be of clinical concern.

What do we know to this point?

With appreciation of the studious investigative reporting of the profession’s historians like Bovine, Foley, Faulkner, and McDowall we can be confident in stating that the idea of subluxation has been explored in a doctoral thesis in 1746, that the idea was evident in writings from the 10th Century, and that the Greek medical writers, going back to around the time of Hippocrates of Kos (460–370 B.C.), were working with the idea and differentiating small dysfunctions in the spine from those of significant cause and blatant appearance such as wounds from battles.

The significance of this knowledge is that the clinical idea so readily dismissed by a few theoretical academics today [8] actually has substance over time.

New knowledge

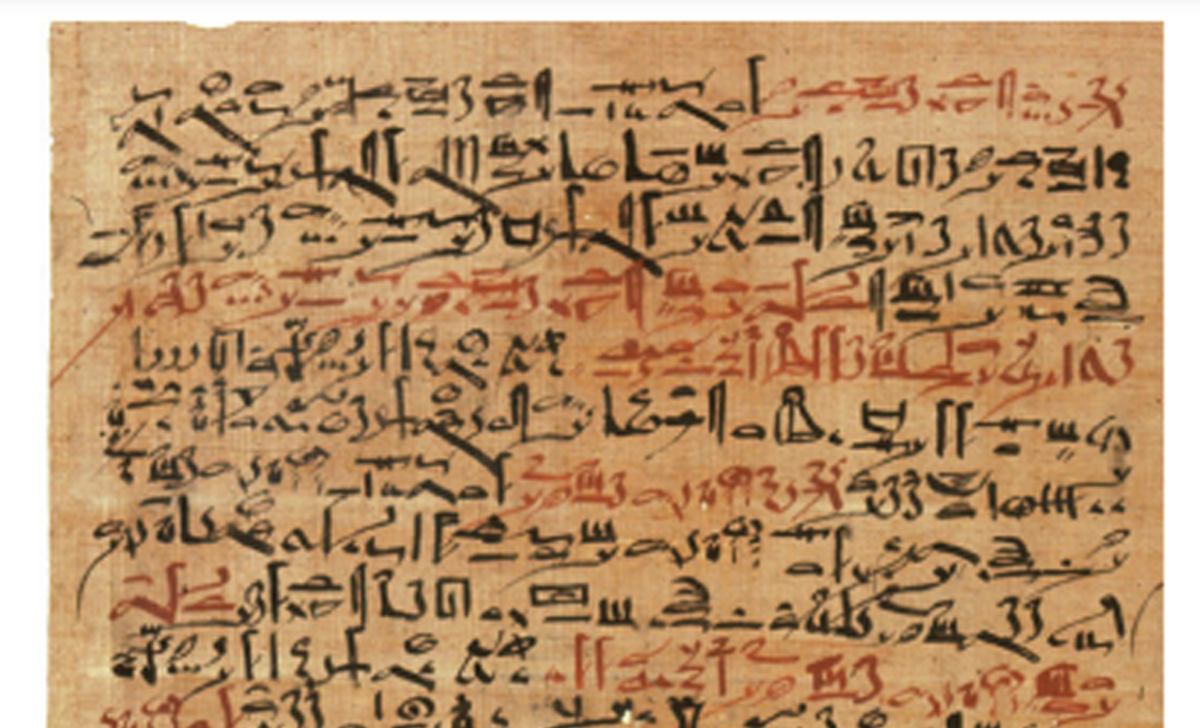

This paper dates the ‘idea of subluxation’ as small spinal dysfunctions affecting health as being expressed within the writings of the medical court of Egypt, around 1,600 BC. The documentation that allows this claim is the Edwin Smith Manuscript. [13] The remainder of this report pivots on this discovery.

Some writers suggest the ‘idea of subluxation’ appeared also in early Chinese writings but give no evidence. This matter is yet to be explored

The Edwin Smith papyrus

The idea of there being a clinical presentation of dysfunction within the spine that was less than a dislocation is evident in the writings of Egyptian medicine from at least the 1600s (BC).

Figure 2 The Edwin Smith Manuscript is a painstaking translation of fragments of a papyrus scroll believed to be a compilation of earlier writings. It is named after the dealer (Figure 2) who bought it in 1862 (Wikipedia) and is a scroll 4.68m in length, held by the New York Historical Society which in the 1920s commissioned Egyptologist James Henry Breasted to translate it. This work of two volumes was published in 1930, following his first work published in 1922 descriptive of ‘The Edwin Smith Papyrus’. In that he noted that:

‘surgery had already reached an advanced stage in the Old Kingdom. A very interesting mention of medical treatises in an Old Kingdom inscription, which demonstrates the existence of books on medical science in the age between 8000 and 2500 BC, will be found in the present editor's Ancient Records’ (I, 242–246).’ [13]

The Foreword by Breasted (13) states:

‘While the copy of the document which has come down to us dates from the Seventeenth Century B.C., the original author's first manuscript was produced at least a thousand years earlier, and was written some time in the Pyramid Age (about 8000 to 2500 B.C.). As preserved to us in a copy made when the Surgical Treatise was a thousand years old or more, a copy in which both beginning and end have been lost, the manuscript nowhere discloses the name of the unknown author. We may be permitted the conjecture, and it is pure conjecture, that a surgical treatise of such importance, appearing in the Pyramid Age, may possibly have been written by the earliest known physician, Imhotep, the great architect-physician who flourished in the Thirtieth Century B.C. In that case the original treatise would have been written over thirteen hundred years before our copy of the Seventeenth Century s.c. was made.’

Blomstedt considers it unlikely that Imhotep was the author on the basis of the papyrus containing a description of cerebrospinal fluid, (14) these are ‘…the earliest known descriptions of the meninges and the cerebrospinal fluid’ and the papyrus is thought to date back to the Old Kingdom, c. 2,700–3,500 BC, an idea Blomstedt feels appears much later. (15) In fact, he suggests Imhotep was instead a sage mastering many arts and not a man specifically of medicine.

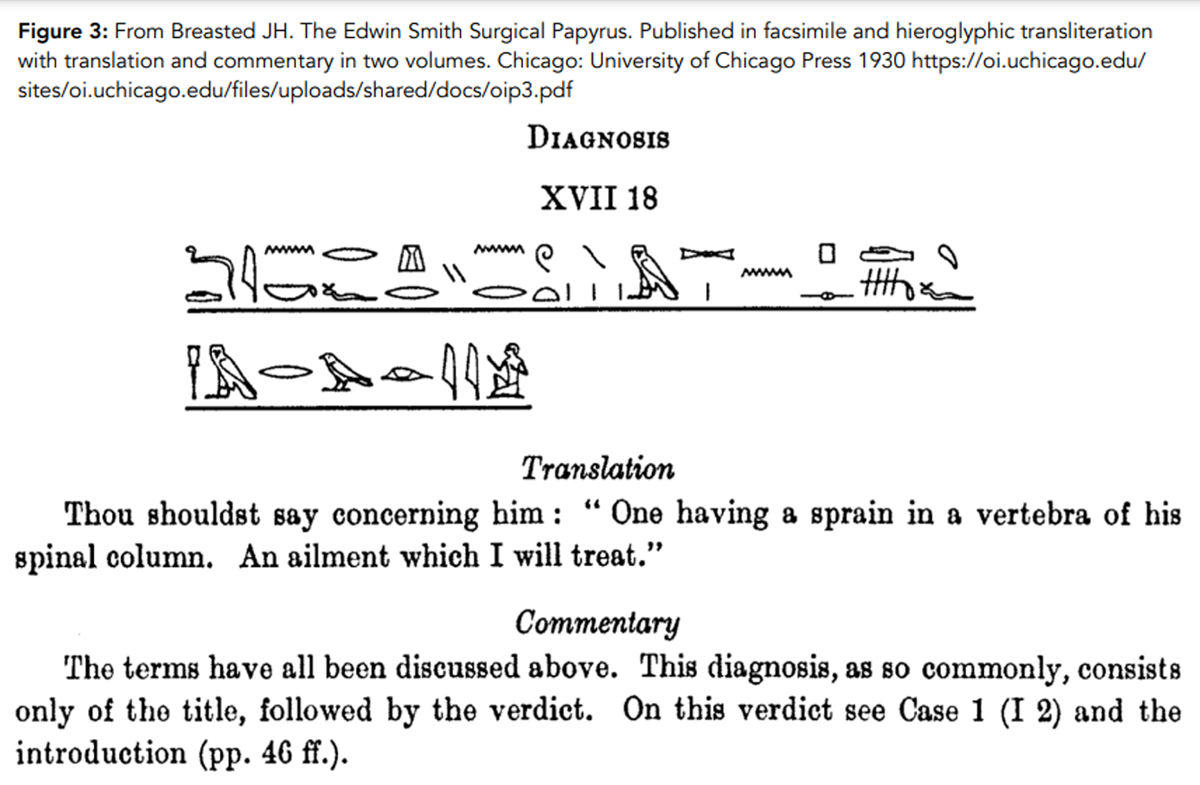

Figure 3 Breasted was also not a medical man but was familiar with the medical context of the papyrus yet unaware of its neurological significance. His transliteration and then translation distinguishes between rational surgical treatments and the medico-magical measures notable in the three other surviving papyri. The papyrus distinguishes minor dysfunction among vertebrae as ‘sprain’ [Case #30] to distinguish from dislocation and fracture, including compound fracture with an open wound. The recommended intervention is similarly graded. The excerpts are given as (Figure 3):

'Case #30: Cervical sprain with disc injury‘Title' Treatment instructions for a wrenching/sprain in the vertebral column of the back of his neck.

‘Examination' If you should examine a man for a wrenching/sprain in the vertebral column of the back of his neck, then you are to say to him:

“Look towards both your shoulders and your chest”.

When he does so, the ‘looking’ he is capable of, is painful.

‘Diagnosis' Then you are to say to him:

“one who suffers from a wrenching/sprain in the vertebral column of the back of his neck (this is) a medical condition I can heal”.

‘Treatment' You have to bind it over fresh meat the first day. Afterward, you should treat with (powdered) alum and honey every day until he recovers.

‘Explanation' As for ‘the wrenching/sprain’, he says about the wrenching apart in intervertebral joints:

“Each vertebra is (still) in its place”.

Figure 4 The diagnosis of a sprain in the spine represented a minor intersegmental dysfunction as the vertebrae were noted as not being dislocated, the matter was one the physician could treat, and recovery was more or less expected. The diagnostic phrase is written in once instance as ‘Thou shouldst say concerning him: “One having a sprain in a vertebra of his spinal column. An ailment which I will treat.”’ An example page of papyrus writings is shown in Figure 4.

Discussion

Aside from tales of being obtained by tomb robbers [14] from a site in Thebes the papyrus was sold to antiquities dealer Edwin Smith in 1862 and on his death in 1906 it passed to his daughter who gifted it to The New York Historical Society which, in 1920, commissioned renowned American Egyptologist James Henry Breasted, [16] working in Luxor, for translation. The papyrus is noted highly as being the first medical document to contains terms such as 'brain', 'spinal cord', 'meninges' and even 'cerebrospinal fluid'. [17] It also refers to the pulse, a role for the heart in circulating blood, and the brain for controlling limbs. [18] I present this extract:‘Evidently written as a practical guide to trauma wounds, perhaps for an army surgeon, the text starts with injuries to the head and works downwards to the torso.

Each case begins with a single word, which translates as “knowledge gained from practical experience.”

Each case then describes a particular injury and explains how to diagnose the problem, probing with the fingers to assess the damage where necessary. But before rushing headlong into treatment, the text divides the cases into one of three categories:’“an ailment I will handle” denotes a wound for which a known treatment existed;

“an ailment I will fight with” indicates a problem for which treatment was uncertain; and

“an ailment for which nothing is done” makes clear that no remedy was known.‘The papyrus describes treatment, in simple steps, for the first two categories, and palliative care for the third. So a gaping head wound is considered eminently treatable by applying fresh meat and linen bandages coated in oil and honey. But if the wound has penetrated the brain, a watch and wait regimen is advised.’

There are two other part translations of the papyrus, Allen of 2005 and Sanchez and Melzer of 2012. (19) The original is notable for omitting religious and magical perceptions. (20)

The author of the papyrus gave three options for dealing with a sick patient:a: ‘to treat the illness (when he anticipated that a cure was likely or that the patient would recover regard-less)’;

b: ‘to contend with the illness (if a cure seemed un-likely but palliation was possible)’; or

c: ‘to avoid treatment altogether (if the case seemed hopeless)’.The decisions were those of the physician to make and led to three diagnoses:

‘an ailment that I will treat’;

‘an ailment with which I will contend’; and

‘an ailment not to be treated’.The consideration for a sprain of the vertebrae, as opposed to a vertebral dislocation, was an ailment that would be treated. This approach represents the oldest known evidence of an inductive process in the history of the human mind, with the treatment lasting ‘until he recovers, until the period of his injury passes by’, or ‘until thou knowest that he has reached decisive point.’ [17] Sprain of a vertebra is a subluxation; Palmer wrote ‘Chiropractic subluxations are known in medical parlance as a “sprain”’ [21]

Contemporary neurologists recognise migraine from the description given in this papyrus. [22] Sanchez and Burridge [23] note:‘the ancient physicians were not deterred from contending with injuries in the presence of basilar skull fractures, traumatic meningismus, skull perforation without overt neurological deficit, drowsiness, limited facial fractures, or closed head injuries without depressed fragments.’

Van Middendorp [24] noted

‘the documented rationale on spinal injuries can still be regarded as the state-of-the-art reasoning for modern clinical practice.

‘the diagnosis of a ‘cervical sprain with disc injury’ (case 30) is associated with the ability to rotate and flex the neck (although painful) …

‘The scroll can be characterised as a well-structured teaching manual guiding a physician’s differential diagnostic process and treatment-decision-making for a range of diagnoses. The papyrus excels in rationality, even more so when considering it originated at the time when written language itself was a recent invention and medicine was at its birth. The cases covered by the papyrus are not likely to represent individual ancient cases, but rather a series of accurately described clinical scenarios based on the clinical knowledge of highly experienced and educationally minded Egyptian physicians. Although the first documented signs of spinal column injuries are – from a modern perspective – fairly non-specific, symptoms of spinal cord injuries have been documented accurately in the scroll. The papyrus contains the first known categorisations of spinal column and spinal cord injuries and covers important clinical prognostic factors which were considered in the treatment decision-making process as reported by the writer.’

Conclusion

This paper may be the first report to chiropractors of the finding that the idea of subluxation is traced to Egyptian medical writings from about 1,600 BC but believed to be drawn from much earlier writings, perhaps as early as the Imhotep (Pyramid Age about 8000 to 2500 BC).

More questions are raised than are answered with this report and a further paper is warranted. Matters which intrigue me are the break in social history from about 1,600 BC and the extent to which the world at that time knew about and accepted what we today term the subluxation. Early reports suggest this idea, descriptive of spinal subluxation, was well known and properly established especially among those who practiced healing.

Other questions relate to how the idea surfaced in Greek medical history and then seemed to carry little significance again until, as Bovine reports, [11] emerging around the 10th Century in the Nicetas Codex. Of noted value is the thesis of Hieronymi, mistakingly called Hieronymus by some, and then how the idea tracked through British medical writings in particular, from Harrison’s reports in the 1820s. [25] Harrison followed Hippocrates’ work of de Articulis, On the Joints. Hieronymi also was aware of the Greek influence and use the word pararthrema in his thesis. [12 p. 4]

This leads to the matter of how the idea was documented in the medical writings of Europe and North America during the 19th Century and these matters are the subject of a future report.

Perhaps the ‘idea of chiropractic’, the ‘subluxation’ or small spinal sprain affecting a person’s well-being, is indeed of historical interest vastly beyond the minds of those few academics which dismiss it without offering evidence. And just maybe this idea really does hold value for all practitioners of manual therapy today, particularly chiropractors.

Addendum

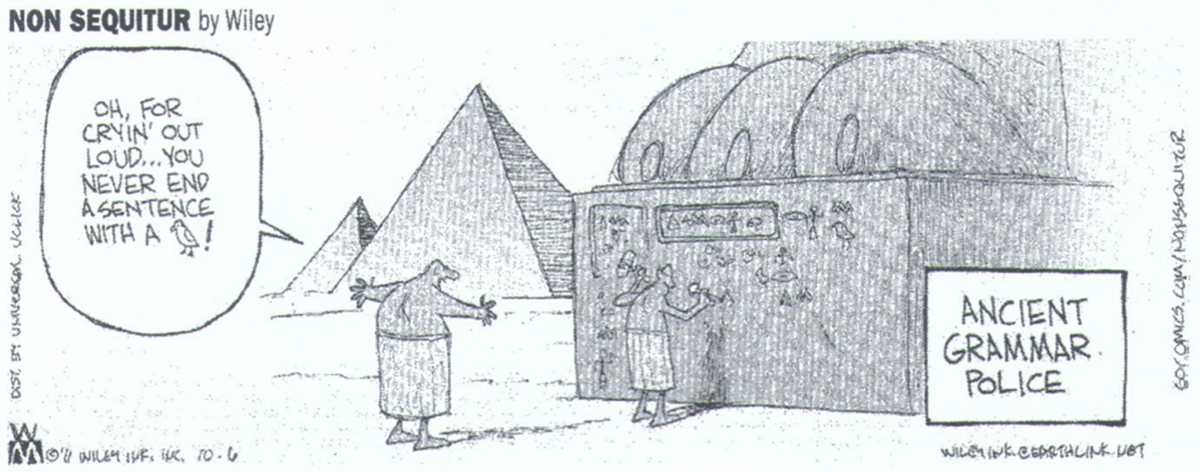

With great respect to the artist I reproduce this delectable observation by Wiley:

References:

Palmer DD.

The Chiropractor.

Davenport: Palmer School of Chiropractic. 1905;1;8:3.Senzon SA.

Personal email 11 February 2020 14:53Palmer DD.

Text-book of the science, art and philosophy of chiropractic

for students and practitioners.

Portland OR: Portland Printing House Co., 2010Bovine G.

William Jasper Atkinson, M.D. (1842-1898):

Chiropractic and the Atkinson connection revisited.

Chiropr Hist. 2017;37(1):17-26.Foley JM. Dr.

Atkinson…found?

Chiropr Hist. 2018;38(1):7-10.Bovine G.

John Atkinson (1854-1904), the English Bonesetter of Park Lane:

His visit to America, bonesetting techniques, and

the Atkinson connection to chiropractic.

Chiropr Hist. 2013;33(1):52-64,Palmer DD. (1914).

The chiropractor.

Los Angeles: Press of Beacon Light Printing Company.The International Chiropractic Education Collaboration.

Clinical and Professional Chiropractic Education:

A Position StatementBovine G.

From the Greek exarthrema, pararthrema, to the Latin luxatio,

subluxatio: Origins and early definitions of the word ‘subluxation’.

Chiropr Hist. 2018;38(1):12-9.Bovine G.

Hipprocrates’ manual manipulation of the spine:

High velocity thrust or pressure technique?

Chiropr Hist. 2015;35(2):80-9.Bovine G.

The Nicetas Code Manuscript: Hippocratic 10th century writings

in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana.

Chiropr Hist. 2018;38(2):14-8.Hieronymi J-H.

The luxationibus and subluxation (thesis).

University of Jena; 1746 (PhD awarded by President Georg.

Erhado Hambergo on 21 Dec 1746).

Thesis facsimile held in the author’s library.Breasted JH.

The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus.

Published in facsimile and hieroglyphic transliteration with

translation and commentary in two volumes.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1930

https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/ shared/docs/oip3.pdfMinagar A, Ragheb J, Kelley RE.

The Edwin Smith surgical papyrus: description and analysis

of the earliest case of aphasia.

J Med Biography; May 2003; 11, 2; ProQuest Central p. 114.

https://doi.org/10.1177/096777200301100214Blomstedt P.

Imhotep and the discovery of cerebrospinal fluid.

Anat Res Int. 2014;2014:256105. DOI 10.1155/2014/256105.

Epub 2014 Mar 13.van Middendorp JJ, Sanchez GM, Burridge AL.

The Edwin Smith papyrus: a clinical reappraisal of the

oldest known document on spinal injuries.

Eur Spine J 2010;19:1815-23

DOI 10.1007/s00586-010-1523-6.Saber A.

Ancient Egyptian surgical heritage.

J Investigative Surg 2010;23:327-34

DOI 10.3109/08941939.2010.515289Moore W.

The Edwin Smith papyrus [Medical Classics]

BMJ 2011;342:d1598

DOI 10.1136/bmj.d1598

‘The first known mention of the brain; the pulse; the role of the heart

in circulating blood … and the brain in controlling limbs.’ Dated to 1600 BC

but copied from a text several hundred years older, and is the

world’s oldest surgical text.Hieronymi J-H. The luxationibus

and subluxation (thesis). University of Jena; 1746

(PhD awarded by President Georg. Erhado Hambergo on 21 Dec 1746).

Thesis facsimile held in the author’s library.Ganz JC.

Edwin Smith Papyrus Case 8: a reappraisal.

J Neurosurg 2014 May;120(5):1238-9.

DOI 10.3171/2013.12.JNS131520. Epub 2014 Jan 3Vargas A, López M, Lillo C, Vargas MJ.

[The Edwin Smith papyrus in the history of medicine]

Spanish. Rev Med Chil 2012 Oct;140(10):1357-62.

DOI 10.4067/S0034-98872012001000020Palmer DD.

The Science of Chiropractic-Its Principles and Adjustments 1e.

Davenport, Ia: Palmer School of Chiropractic, 1906:25.York GK 3rd, Steinberg DA.

Chapter 3: Neurology in ancient Egypt.

Handb Clin Neurol 2010;95:29-36.

DOI 10.1016/S0072-9752(08)02103-9Sanchez GM, Burridge AL.

Decision making in head injury management in the Edwin Smith Papyrus.

Neurosurg Focus 2007;23(1):E5

DOI 10.3171/foc.2007.23.1.5van Middendorp JJ, Sanchez GM, Burridge AL.

The Edwin Smith papyrus: a clinical reappraisal of the

oldest known document on spinal injuries.

Eur Spine J 2010;19:1815-23

DOI 10.1007/s00586-010-1523-6.Harrison E.

Pathological and Practical Observations on Spinal Diseases.

London: printed for Thomas and George Underwood, 1827

Return to SUBLUXATION THEORY

Since 9-01-2024

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |