Return to Work Helps Maintain Treatment Gains

in the Rehabilitation of Whiplash InjuryThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Pain 2017 (May); 158 (5): 980–987 ~ FULL TEXT

Michael Sullivan, Heather Adams, Pascal Thibault, Emily Moore, Junie S Carriere, Christian Larivière

Faculty of Health and Behavioural Sciences,

The University of Queensland,

Brisbane, Australia

This study examined the relation between return to work and the maintenance of treatment gains made over the course of a rehabilitation intervention. The study sample consisted of 110 individuals who had sustained whiplash injuries in rear collision motor vehicle accidents and were work-disabled at the time of enrolment in the study. Participants completed pre- and post-treatment measures of pain severity, disability, cervical range of motion, depression, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and catastrophizing. Pain severity was assessed again at 1–year follow-up. At 1–year follow-up, 73 participants had returned to work and 37 remained work-disabled. Analyses revealed that participants who returned to work were more likely to maintain treatment gains (77.5%) than participants who remained work-disabled (48%), x2 = 6.3, P < 0.01.

The results of a regression analysis revealed that the relation between return to work and the maintenance of treatment gains remained significant (β = 0.30, P < 0.01), even when controlling for potential confounders such as pain severity, restricted range of motion, depression, and pain catastrophizing. The Discussion addresses the processes by which prolonged work-disability might contribute to the failure to maintain treatment gains. Important knowledge gaps still remain concerning the individual, workplace, and system variables that might play a role in whether or not the gains made in the rehabilitation of whiplash injury are maintained. Clinical implications of the findings are also addressed.

Keywords: Return to work, Work-disability, Pain, Disability, Whiplash

The FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Return to work is considered a desirable treatment objective for individuals who have sustained whiplash injuries. The position or policy statements of many injury insurers and clinical practice guidelines argue for placing return to work as a priority in the physical rehabilitation of a wide range of musculoskeletal injuries. [6, 7, 29, 33, 52] Evidence highlighting the deleterious health and mental health consequences of prolonged unemployment is frequently marshalled to support the view that return to work should be a central objective of a rehabilitation plan. [35, 47]

The health benefits of returning to work following a whiplash injury have been inferred more than they have been demonstrated. The bulk of research in this area has focused on the deleterious consequences of prolonged unemployment rather than the health benefits of returning to work. [35] Research from several countries shows that prolonged unemployment is associated with a wide range of adverse health and mental health outcomes. [4, 28, 32, 53] However, research showing a relation between prolonged unemployment and negative health or mental health outcomes cannot be taken as evidence that returning to work following a period of work-disability will yield positive health or mental health benefits.

In this study, the health benefits of return to work were assessed in relation to the maintenance of treatment gains made following participation in a rehabilitation program for whiplash injury. Rehabilitation interventions for whiplash injury have been shown to yield significant reductions in pain and disability. [3, 10, 47] Following participation in rehabilitation interventions, a certain percentage of individuals with whiplash injuries will return to work, whereas others will remain work-disabled. [14, 38, 39, 47] The distribution of return-to-work outcomes following completion of a rehabilitation intervention provides an ideal context for assessing the potential health benefits of returning to work. On the basis of research pointing to the adverse consequences of prolonged unemployment, it can be predicted that return to work will be associated with a greater likelihood that treatment gains will be maintained. [36, 40] However, it is also possible that treatment gains might be less likely to be maintained in individuals who return to work. This prediction would be based on the notion that excessive demands on a musculoskeletal system that has been compromised by injury might lead to worsening of symptoms. [50] Finally, return to work could be shown to have no relation to the probability of maintaining treatment gains. To date, no study has examined the relation between return to work and the probability of maintaining treatment gains in individuals with whiplash injuries.

This study examined the relation between return to work and the maintenance of treatment gains following participation in a rehabilitation intervention for whiplash injury. Treatment gains were operationally defined as reductions in the severity of pain symptoms and self-rated improvement. Work-disabled individuals with whiplash injuries completed pre- and post-treatment measures of pain severity. Maintenance of treatment gains was assessed at 1–year follow-up. Predictive analyses controlled for potential confounders (eg, psychosocial variables, symptom severity, and disability) of the relation between return to work and the maintenance of treatment gains.

Methods

Participants

The study sample consisted of 110 (62 men, 48 women) individuals who had sustained whiplash injuries in rear collision motor vehicle accidents and were work-disabled at the time of recruitment. The mean age of the sample was 36.6 years with a range of 25 to 60 years. The mean duration of work disability was 18.3 weeks with a range of 8 to 40 weeks. The majority of participants (82%) had completed at least 12 years of education. Approximately, half of the sample (46%) was married or living with a common-law partner. At the time of enrolment in the study, all participants were work-disabled and receiving salary indemnity through a no-fault provincial insurance system (Socie´ te´ de l’assurance automobile du Que´ bec).

Procedure

Participants were recruited between June 2010 and August 2013 from one of 2 rehabilitation centres in Montreal, Canada. The clinics from which patients were recruited were part of a network of rehabilitation centres providing services for the state motor vehicle insurer. A 7–week standardized program of intervention was offered at each rehabilitation centre. The programs were characterized by a functional restoration and activity reintegration orientation focusing on education, mobilisation and exercise, and the development of self-management skills. The program of rehabilitation offered by the clinics from which patients were recruited is described in more detail elsewhere. [44]

Eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of a whiplash-associated disorder (grade II) and being work-disabled at the time of recruitment. Advertisements were placed in the collaborating clinics, and interested individuals were instructed to contact the clinic coordinator. Volunteers signed a consent form as a condition of participating in the study. The research was appred by the Ethics Review Committee of McGill University.

Participants completed measures of pain severity, depression, posttraumatic stress, pain catastrophizing, and functional disability. Physical function evaluation included assessment of active range of motion. The variables included in the study were intended to provide indices of health and mental health status that might impact on the probability of maintaining treatment gains. The choice of variables was also guided by the results of previous research on determinants of recovery trajectories following whiplash injury. [1, 2, 12, 42] Assessments were completed during the first and final weeks of the 7–week rehabilitation program. Participants were contacted by telephone 1 year after completion of the rehabilitation intervention and were asked to respond to questions about their present pain severity, the changes in their health condition during the previous 12 months, the treatments they had received during the previous 12 months, and their employment status.

Measures

Demographic and injury-related variables

Participants were asked to respond to questions concerning their age, sex, marital status, education, occupation, and medication use. Crash-related characteristics (ie, speed of collision, use of head rest, and use of seat belt) were also assessed.

Pain severity

Participants were asked to rate the severity of their pain on an 11–point numerical rating scale (NRS) with the endpoints (0) no pain and (10) excruciating pain. The total number of pain sites (range 5 0–4) was computed from a body drawing (neck, back, upper extremity, and lower extremity).

Range of motion

The maximum active cervical range of motion (CROM; flexion and extension, left and right lateral flexion, and left and right rotation) was assessed with a CROM device. [22] Measurement of active CROM has high intra- and inter-rater reliability and has been shown to predict long-term outcomes in patients with whiplash injuries. [21, 42]

Posttraumatic stress symptoms

The Impact of Events Scale—Revised (IES-R) was used to assess symptoms of posttraumatic stress. On this measure, respondents are asked to rate the degree of distress they experience with different cognitive and emotional aspects of posttraumatic stress on a 5–point rating scale with the endpoints (0) not at all and (4) extremely. The IES-R has been shown to be a reliable and valid index of posttraumatic symptoms. [11, 54] Scores on the IES-R have been shown to discriminate between individuals with and without a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder. [9]

Depression

The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) [8] was used as a selfreport measure of depressive symptom severity. The BDI-II consists of 21 statements describing various symptoms of depression and respondents choose the statement that best describes how they have been feeling over the past 2 weeks. Responses are summed to yield an overall index of severity of depressive symptoms. The BDI-II has been shown to be a reliable and valid index of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic pain and primary care medical patients. [5]

Catastrophizing

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [46] was used to assess catastrophic thinking related to pain. On this measure, respondents rate the frequency with which they experience each of the 13 different thoughts and feelings when in pain. The PCS has been shown to have high internal consistency (coefficient alpha 5 0.87), and to be associated with pain experience, pain behavior, and disability. [45, 49]

Self-rated disability

The Neck Disability Index (NDI) was used as a measure of selfrated disability associated with neck pain. [51] The NDI consists of 10 groups of statements describing levels of disability resulting from neck pain in different domains of daily life. Responses are summed to produce an overall index of disability where higher scores reflect greater disability. The NDI has been shown to be a reliable and valid index of disability associated with cervical spine disorders. [34, 51, 57]

One-year follow-up interview

One year following the termination of the rehabilitation intervention, participants were contacted by telephone and interviewed about their current pain symptoms, their perceived improvement since the termination of treatment, their employment status, and their health care utilisation since treatment termination.

Follow-up pain severity

Participants were asked to verbally rate the severity of their pain on an 11–point NRS with the endpoints (0) no pain and (10) excruciating pain.

Follow-up self-rated improvement

Participants responded to a question about the degree of improvement in their condition they had experienced since the termination of the rehabilitation intervention in which they had been enrolled. Participants were asked to choose one of the following response options (1) condition improved, (2) condition worsened, or (3) condition remained the same.

Follow-up employment status

Participants were asked whether they had returned to work since the termination of the rehabilitation intervention in which they were enrolled. The date at which they had returned to work, whether they had been able to maintain work, and the nature of their employment was also recorded. For the purposes of this article, current employment status was categorized as having resumed; (1) full-time work, (2) part-time work, or remained (3) work-disabled.

Follow-up treatment involvement

Participants were asked to report the different treatments (eg, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and psychotherapy) they had received since the termination of the rehabilitation intervention. The total number of interventions reported was used as index of health care utilisation. Participants also reported the different types of pain medications they were currently taking (eg, NSAIDs, opiates, and psychoactive drugs). Each class of medication was dichotomised as yes or no reflecting whether participants had, or had not, been prescribed the medication. Follow-up treatment involvement

Data analytic approach

Only limited information was available on participants who did not volunteer to participate (N = 36) in the study. Analyses of demographic information (age, sex, and education), pain duration, pretreatment pain severity, and self-rated disability revealed no significant differences between individuals who volunteered and who declined participation in the study.

One hundred forty-eight individuals agreed to participate in this study. Of these, 10 participants (6%) did not complete the posttreatment evaluation. Information regarding the cause of the missing data was not available. Twenty-eight participants (19%) could not be reached for the 1–year follow-up interview. Analyses were conducted to compare participants with complete (n = 110) and incomplete data (n = 38) on sex, age, education, pain duration, pretreatment pain intensity, and self-reported disability. No significant differences were found on any of these comparisons.

Repeated measures analysis of variance was used to examine how reductions in pain and maintenance of treatment gains varied as a function of occupational re-engagement. Analyses pertaining to the maintenance of treatment gains were also conducted in relation to indices of “clinically meaningful” changes in pain. Participants were classified as having shown clinically meaningful improvement if their pain score decreased by 2 points or more from pre- to post-treatment. The approach to defining clinically meaningful response to treatment is consistent with research on recommended cut scores on pain severity scales and IMMPACT recommendations for interpreting pain treatment outcomes. [17, 23] Chi-square analyses were used to address the relation between occupational re-engagement and self-rated improvement at follow-up.

The primary outcome variables were pain severity and selfrated improvement. Because maintenance of treatment gains could be influenced by the severity or complexity of participants’ whiplash injuries, a number of potential confounders were also assessed. Indices of condition severity or complexity included severity of disability (ie, CROM, self-rated disability), injury-related psychosocial factors (ie, posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression, and pain catastrophizing), medication use, and additional treatment.

T tests were used to compare occupationally re-engaged and work-disabled participants on pre- and post-treatment measures, and Pearson correlations were used to identify potential confounders of the relation between return to work and the maintenance of treatment gains. Multiple regression analysis was used to assess the value of return-to-work status in predicting the maintenance of treatment gains while controlling for potential confounders. Tolerance coefficients for the regression analysis were greater than 0.55 indicating no problem of multicollinearity. All analyses were conducted with SPSS Version 23.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 Demographic information, mean values, and SDs on all study variables are presented in Table 1. On the basis of mean values on the Pain NRS, the BDI-II, and the IES, the study sample would be characterized as being in the early stages of chronicity, and experiencing symptoms of pain, depression, and posttraumatic stress of moderate severity. Most participants reported experiencing pain in more than one bodily region. Mean scores on measures of pain severity, self-reported disability, depression, and posttraumatic stress symptoms are comparable with those reported in previous studies examining recovery trajectories following whiplash injury. [42, 43, 48]

Return to work and the maintenance of treatment gains

Following the rehabilitation intervention, 42 participants (38%) returned to work full time, 31 participants returned to work part time (28%), and 37 participants (34%) remained work-disabled. On average, return to work occurred 2.2 weeks (range 1–8 weeks) following termination of the rehabilitation intervention. The majority of participants returned to their preinjury employment. Two participants who had resumed part-time employment later discontinued. These participants were reclassified as being work-disabled.

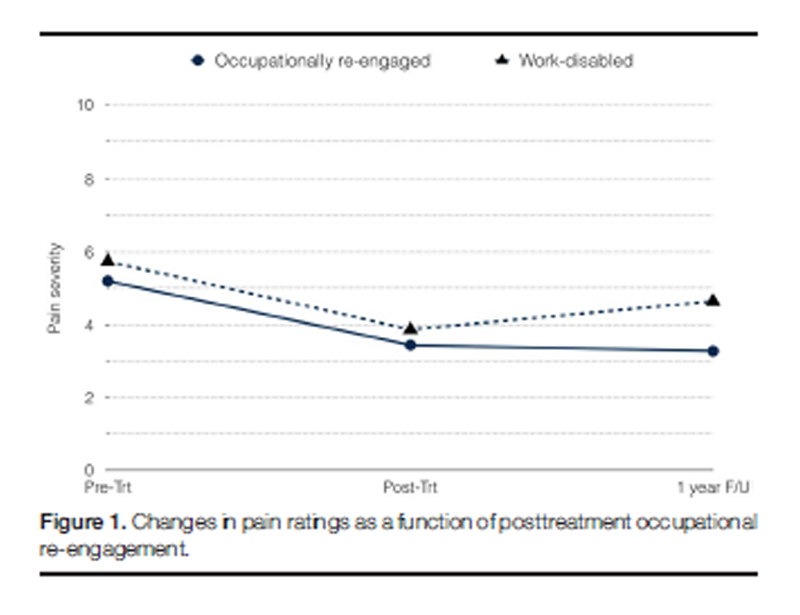

Figure 1 A repeated measures analysis of variance was conducted on participants’ pain ratings to examine whether changes in pain ratings over time varied as a function of occupational reengagement. Participants were considered to be occupationally re-engaged if they were currently working full or part time; participants were considered to be work-disabled if they were currently not working. The results of this analysis are presented in Figure 1. The analysis yielded significant main effects for occupational re-engagement, F(1,108) = 7.30, P < 0.01, and time, F(2,216) = 52.1, P < 0.001. Main effects were qualified by a significant 2–way interaction, F(2,216) = 4.5, P < 0.01.

Participants who resumed employment following the rehabilitation intervention showed significant reductions in pain from preto post-treatment, t(72) = 8.5, P < 0.001, and there was no significant difference between their posttreatment and follow-up pain ratings, t(72) = 0.96, P = 0.44. Participants who remained work-disabled showed similar reductions in pain from pre- to post-treatment, t(36) = 7.2, P < 0.001, but pain ratings increased significantly from posttreatment to follow-up assessment, t(36) = 23.0, P < 0.01. On average, participants who remained workdisabled lost 46% of the gains they had made through the course of the rehabilitation intervention.

The relation between return to work and the maintenance of treatment gains was also examined according to criteria for “clinically meaningful” changes in pain (ie, reductions in pain of 2 points or more). Participants who showed clinically meaningful improvement were considered to have failed to maintain treatment gains if their follow-up pain rating had increased by at least 2 points, relative to the posttreatment evaluation. On this basis, 69 participants (63%) showed clinically meaningful improvement in pain. Of the participants who showed clinically meaningful improvement in pain, 24 (35%) failed to maintain treatment gains at 1–year follow-up. A x2 analysis revealed that participants who returned to work were more likely to maintain treatment gains (77.5%) than participants who remained work-disabled (48%), x2 = 6.3, P < 0.01. Only a minority of participants (23%) who returned to work lost all the gains they made in treatment, whereas the majority (76%) of participants who remained work-disabled lost all the gains they had made in treatment, x2 = 7.7, P < 0.01.

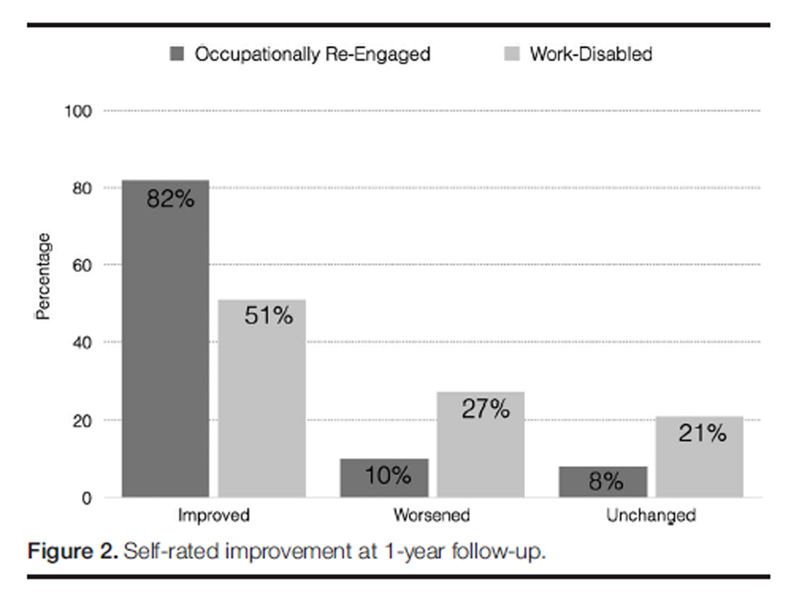

Figure 2 During the 1–year follow-up interview, participants were asked to indicate whether their condition has improved, worsened, or stayed the same since the termination of the rehabilitation intervention. A x2 analysis was conducted to examine the relation between return to work and participants’ retrospective appraisal of the changes in their health condition over the previous 12 months. The results of a x2 are presented in Figure 2. The analysis revealed that participants who returned to work were significantly more likely (82%) than participants who remained work-disabled (51%) to indicate that their condition had improved since the termination of the rehabilitation intervention, x2 (2) 5 11.5, P < 0.01.

Controlling for confounders

Table 2 A series of t tests were conducted to examine whether individuals who returned to work differed from individuals who did not return to work on various indices of clinical severity. These analyses were conducted to address the possibility that the failure to maintain gains by individuals who did not return to work was due to the latter having a more serious or debilitating condition. As shown in Table 2, individuals who did not return to work were more chronic at the time of admission, t(108) = 2.6, P < 0.01, rated their pain as more intense at the time of admission, t(108) = 2.0, P < 0.05, showed reduced posttreatment neck flexion, t(108) = 2.9, P <0.01, extension, t(108) = 3.0, P < 0.01, right lateral flexion, t(108) = 2.3, P < 0.05, left lateral flexion, t(108) = 2.2, P < 0.05, right rotation, t(108) = 3.2, P < 0.001, left rotation, t(108) = 3.6, P < 0.001, reported more severe posttreatment depressive symptoms, t(108) = 2.2, P < 0.05, more severe posttreatment self-rated disability, t(108) = 3.6, P < 0.001, and obtained higher PCS scores at posttreatment, t(108) = 3.0, P < 0.01.

Of the severity-relevant variables that distinguished between occupationally re-engaged and work-disabled participants, only the following were significantly correlated with change in pain symptoms from posttreatment to 1–year follow-up: pretreatment pain severity, right lateral flexion, right rotation, left rotation, posttreatment BDI-II, posttreatment NDI, and post-treatment PCS. As such, only the latter variables met criteria for consideration as potential confounders.

Table 3 A multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine whether the relation between return to work and the maintenance of treatment gains remained significant even when controlling for potential confounders (Table 3). This analysis was conducted on the subgroup (N = 68) of participants who showed clinically meaningful improvement in pain through the course of the rehabilitation intervention. In this analysis, the change in pain ratings from posttreatment to 1–year follow-up was used as the dependent variable. In step 1 of the analysis, the following variables were entered as a block: pretreatment pain severity, right lateral flexion, and right and left rotation. The variables entered in step 1 of the analysis contributed significant variance to the prediction of maintenance of treatment gains, F(4,63) = 4.9, P < 0.001. In step 2 of the analysis, the following variables were entered: posttreatment scores on the BDI-II, NDI, and PCS. The variables entered in step 2 of the analysis contributed significant variance to the prediction of the maintenance of treatment gains, F(3,60) = 2.9, P < 0.05. Return-to-work status at 1–year follow-up was entered in the final step of the analysis. Return-to-work status remained a significant predictor of changes in pain ratings following termination of the rehabilitation intervention, even when controlling for all potential confounders, F(1,59) = 6.4, P < 0.01.

Discussion

This study sought to determine whether return to work conferred any health benefits following rehabilitation of whiplash injury. The main finding of the study was that individuals who returned to work following participation in a rehabilitation intervention were more likely to maintain treatment gains than individuals who did not return to work. Return to work did not lead to amelioration in pain symptoms, but rather, work absence contributed to a worsening of pain symptoms.

The findings of this study are consistent with a large body of research highlighting the deleterious health consequences of prolonged work absence. Numerous investigations have shown that unemployment is associated with increased all-cause mortality. [28, 32, 53] Unemployment has also been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and suicide. [24] Many population studies show that being out of work places someone at increased risk of substance abuse, divorce, and violent behaviour. [4] The findings of this study extend previous research in showing that prolonged work absence following whiplash injury impacts negatively on the maintenance of gains made following participation in a rehabilitation intervention.

The relation between prolonged work absence and failure to maintain treatment gains could not be explained in terms of end-of-treatment differences in clinical severity. As expected, participants who remained work-disabled had reduced physical function as assessed by range of motion and self-rated disability. Participants who remained work-disabled also obtained elevated scores on measures of depression and pain catastrophizing. However, the relation between return to work and the maintenance of treatment gains remained significant even when controlling for end-of-treatment differences in neck range of motion, self-rated disability, depression, and pain catastrophizing.

Although the correlational nature of the study limits the strength of conclusions that can be drawn about the direction of influence among study variables, the temporal ordering of return to work and the follow-up assessment favor an explanation where return to work exerts an influence on the maintenance of treatment gains. On average, participants who returned to work did so within 2 weeks of termination of the rehabilitation intervention. The follow-up assessment of pain severity used to determine maintenance of treatment gains was conducted 1–year following termination of the rehabilitation intervention. Because return to work occurred on average 10 months before the final pain assessment, the results are most consistent with the view that return to work contributed to the maintenance of treatment gains.

In a previous study, high levels of posttreatment pain catastrophizing were shown to predict the failure to maintain treatment gains following participation in a rehabilitation intervention. [31] In this study, posttreatment pain catastrophizing was associated with increases in follow-up pain severity in univariate analyses, but did not emerge as a significant unique predictor of the maintenance of treatment gains in multivariate analyses. It is likely that the shared variance between pain catastrophizing and other predictor variables reduced the probability that any one variable would make a significant unique contribution in the regression equation. In support of this explanation, when only pain catastrophizing and return-to-work status were included as independent variables in the regression, both variables emerged as significant unique predictors of the maintenance of treatment gains.

There are several possible pathways by which prolonged work absence following whiplash injury might contribute to the failure to maintain treatment gains. Individuals who do not return to work might engage in a lower level of physical activity, in turn, compromising their recovery potential. [30] Prolonged work absence might also be associated with increases in symptoms of mental health problems such as depression or anxiety that could exacerbate pain symptoms. [55, 56] It is also possible that ongoing stresses related to the disability claims process, pressure to prove the basis for ongoing disability, and financial strain might also contribute to failure to maintain treatment gains in individuals who do not return to work. [18, 19] The pathways by which prolonged work absence following whiplash injury leads to failure to maintain treatment gains will need to be clarified by future research.

Return to work did not guarantee the maintenance of treatment gains. Results revealed that 23% of participants who returned to work did not maintain treatment gains. Inactivity and stress have been associated with poor recovery outcomes following whiplash injury. [30, 41] It is possible that participants who returned to employment that was sedentary and/or stressful might have been at higher risk for losing the gains they made in rehabilitation. On the basis of the data collected in the present study, it was not possible to identify the determinants of failure to maintain treatment gains in participants who returned to work.

Although return to work was not associated with health benefits, at least defined as further reduction in pain symptoms, participants who returned to work were more likely than participants who remained work-disabled to report that their condition had “improved” during the follow-up period. It is possible that other symptoms or correlates of whiplash injury might have continued to improve during the follow-up period. Research on occupational injury suggests that return to work can contribute to reductions in emotional distress symptoms, increased social contact, feelings of accomplishment, or reduced financial stresses. [26, 27, 35, 58] Similar benefits might be associated with return to work in individuals who have sustained whiplash injuries.

The findings of this study argue strongly for placing return to work as a priority in the treatment of individuals who have sustained whiplash injuries. Primary care practice places emphasis on symptom management and mobilisation. [25, 37] It has been suggested that primary care practitioners do not necessarily consider their role to include involvement in the return-to-work process. [20] An implicit assumption guiding early intervention is that return to work will occur automatically once symptoms are effectively controlled.

However, research indicates that symptom severity is only a partial determinant of workdisability and symptom reduction is not a prerequisite for successful occupational reintegration. [13, 16] In addition, considering symptom control as a prerequisite of return to work might unnecessarily prolong the work-disability period, ultimately impacting negatively on the likelihood of successful work reintegration. The results of this study suggest that treatment gains such as pain reduction might not be maintained if return to work is not achieved. Neglecting to place return to work as a central treatment objective in the treatment of whiplash injury could be associated with high costs. In addition to the increase in health care costs associated with failing to maintain treatment gains, the resurgence of symptoms might be experienced as a treatment failure that could impact negatively on individuals’ expectations for future treatment outcomes or recovery potential. [15]

Some degree of caution must be exercised in the interpretation of the study findings. Participants were recruited from multidisciplinary rehabilitation centres. Only a minority of individuals with whiplash injuries are referred to these centres. In addition, all participants were work-disabled. These sample characteristics necessarily have implications for the generalizability of findings. It is also necessary to consider that a wide range of symptomrelated, treatment-related, psychosocial, and workplace factors that have been shown to be associated with recovery outcomes and return to work were not assessed in this study. Whether the relation between return to work and maintenance of treatment gain is independent of these factors remains to be clarified by future research. It is also important to note that the sample consisted only of individuals who were working full time before the current period of work absence. It is not clear whether the findings are generalizable to individuals who were not gainfully employed before injury.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study suggest that the return to work contributes to the maintenance of treatment gains made over the course of rehabilitation interventions for whiplash injury. If replicated, these findings would have important implications for treatment planning for work-disabled individuals with whiplash injuries. By placing return to work as a central treatment objective of rehabilitation interventions, the probability of maintaining treatment gains might be substantively increased. Considering return to work as part of intervention plan to maintain treatment-related reductions in pain symptoms would also impact positively on the long-term cost-effectiveness of symptomatic treatment of whiplash injury.

Research on the determinants of the maintenance of treatment gains following rehabilitation of whiplash injury is still in its infancy. To date, only a handful of studies have examined the course of symptom severity and disability after termination of a rehabilitation intervention. Important knowledge gaps still remain concerning the individual, workplace, and system variables that might play a role in whether or not the gains made in the rehabilitation of whiplash injury are maintained. These knowledge gaps will need to be addressed by future research.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-130296).

REFERENCES

Adams H, Ellis T, Stanish WD, Sullivan MJ.

Psychosocial factors related to return to work

following rehabilitation of whiplash injuries.

J Occup Rehabil 2007;17:305–15.Agnew L, Johnston V, Landen Ludvigsson M, Peterson G, Overmeer T, Johansson G, Peolsson A.

Factors associated with work ability in patients with chronic

whiplash-associated disorder grade II-III: a cross-sectional analysis.

J Rehabil Med 2015;47:546–51.Angst F, Gantenbein AR, Lehmann S, Gysi-Klaus F, Aeschlimann A, Michel BA, Hegemann F.

Multidimensional associative factors for improvement in pain, function,

and working capacity after rehabilitation of whiplash associated disorder:

a prognostic, prospective outcome study.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:130.Arcaya M, Glymour MM, Christakis NA, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV.

Individual and spousal unemployment as predictors of smoking and drinking behavior.

Soc Sci Med 2014;110:89–95.Arnau RC, Meagher MW, Norris MP, Bramson R.

Psychometric evaluation of the beck depression inventory-II

with primary care medical patients.

Health Psychol 2001;20:112–19.Athanasou JA.

Return to work following whiplash and back injury: a review and evaluation.

Med Leg J 2005;73:29–33.Authority MA.

Guidelines for the management of whiplash associated disorders.

Sydney, Australia: Motor Accident Authority, 2014.Beck A, Steer R, Brown GK.

Manual for the beck depression inventory—II.

San Antonio: Psychological Corporation, 1996.Beck JG, Grant DM, Read JP, Clapp JD, Coffey SF, Miller LM, Palyo SA.

The impact of event scale-revised: psychometric properties

in a sample of motor vehicle accident survivors.

J Anxiety Disord 2008;22:187–98.Bohman T, Cote P, Boyle E, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Skillgate E.

Prognosis of patients with whiplash-associated disorders consulting

physiotherapy: development of a predictive model for recovery.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:264.Brunet A, St. Hilaire A, Jehel L, King S.

Validation of the french version of the impact of event scale—revised.

Can J Psychiatry 2002;20:174–82.Buitenhuis J, de Jong PJ, Jaspers JP, Groothoff JW.

Relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder

symptoms and the course of whiplash complaints.

J Psychosom Res 2006;61:681–9.Buitenhuis J, de Jong PJ, Jaspers JP, Groothoff JW.

Work disability after whiplash: a prospective cohort study.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:262–7.Carriere JS, Thibault P, Milioto M, Sullivan MJL.

Expectancies mediate the relations among pain catastrophizing,

fear of movement, and return to work after whiplash injury.

J Pain 2015;16:1280–7.Carroll LJ.

Beliefs and Expectations for Recovery, Coping, and Depression in

Whiplash-Associated Disorders: Lessening the Transition to Chronicity

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011 (Dec 1); 36 (25 Suppl): S250–S256Costa-Black KM, Loisel P, Anema JR, Pransky G.

Back pain and work.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:227–40.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT. et al

Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes

in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations.

J Pain 2008;9:105–21.Elbers NA, Collie A, Hogg-Johnson S, Lippel K, Lockwood K, Cameron ID.

Differences in perceived fairness and health outcomes in

two injury compensation systems: a comparative study.

BMC Public Health 2016;16: 1–13.Elbers NA, Hulst L, Cuijpers P, Akkermans AJ, Bruinvels DJ.

Do compensation processes impair mental health? A meta-analysis?

Injury 2013;44:674–83.Guzman J, Yassi A, Cooper JE, Khokhar J.

Return to work after occupational injury.

Family physicians’ perspectives on soft-tissue injuries.

Can Fam Physician 2002;48:1912–19.Hendriks EJ, Scholten-Peeters GG, van derWindt DA, Neeleman-van der Steen CW.

Prognostic factors for poor recovery in acute whiplash patients.

PAIN 2005;114:408–16.Hole D, Cook J, Bolton J.

Reliability and concurrent validity of two instruments for measuring

cervical range of motion: effects of age and gender.

Man Ther 1995;1:36–42.Jensen MP, Chen C, Brugger AM.

Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores:

a reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain.

J Pain 2003;4:407–14.Jin RL, Shah CP, Svoboda TJ.

The impact of unemployment on health: the evidence.

CMAJ 1998;168:178–82.Kwan O, Friel J.

Clinical practice guideline for the physiotherapy

of patients with whiplash-associated disorders.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:2082–3.Lotters F, Hogg-Johnson S, Burdorf A.

Health status, its perceptions, and effect on return to work and recurrent sick leave.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1086–92.MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche RL, Irvin E.

Systematic review of the qualitative literature

on return to work after injury.

Scan J Work Environ Health 2006;32:257–69.Mathers CD, Schofield DJ.

The health consequences of unemployment: the evidence.

Med J Aust 1998;168:178–82.McClune T, Burton AK, Waddell G. Whiplash associated disorders: a review of the literature

to guide patient information and advice.

Emerg Med J 2002;19:499–506.Miro J, Nieto R, Huguet A.

Predictive factors of chronic pain and disability in whiplash: a delphi poll.

Eur J Pain 2008;12:30–47.Moore E, Thibault P, Adams A, Sullivan MJL.

Catastrophizing and painrelated fear predict failure to maintain treatment gains

following participation in a pain rehabilitation program.

PAIN Reports 2016;1:e567.Quaade T, Engholm G, Johansen AM, Moller H.

Mortality in relation to early retirement in Denmark:

a population-based study.

Scand J Public Health 2002;30:216–22.Rebbeck TJ, Refshauge KM, Maher CG.

Use of clinical guidelines for whiplash by insurers.

Aust Health Rev 2006;30:442–9.Riddle D, Stratford P.

Use of generic versus region-specific functional status measures

on patients with cervical spine disorders.

Phys Ther 1998;78:951–63.Rueda S, Chambers L, Wilson M, Mustard C, Rourke SB, Bayoumi A, Raboud J, Lavis J.

Association of returning to work with better health

in working-aged adults: a systematic review.

Am J Public Health 2012;102: 541–56.Rushton A, Wright C, Heneghan N, Eveleigh G, Calvert M, Freemantle N.

Physiotherapy rehabilitation for whiplash associated disorder II:

a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

BMJ Open 2011;1:e000265.Scholten-Peeters GG, Bekkering GE, Verhagen AP, van Der Windt DA, Lanser K.

Clinical practice guideline for the physiotherapy

of patients with whiplash-associated disorders.

Spine (Philia Pa 1976) 2002;27:412–22.Scott W, Sullivan MJL.

Validity and determinants of clinicians’ return to work

judgments for individuals following whiplash injury.

Psychol Inj L 2010;3:220–9.Scott W, Wideman TH, Sullivan MJ.

Clinically meaningful scores on pain catastrophizing before and after

multidisciplinary rehabilitation: a prospective study of

individuals with subacute pain after whiplash injury.

Clin J Pain 2014;30:183–90.Southerst D, Nordin M, Côté P, et al.

Is Exercise Effective for the Management of Neck Pain and

Associated Disorders or Whiplash-associated Disorders?

A Systematic Review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic

Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

Spine J 2016 (Dec); 16 (12): 1503–1523Sterling M, Carroll LJ, Kasch H, Kamper SJ, Stemper B.

Prognosis after whiplash injury: where to from here?

Discussion paper 4.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:S330–334.Sterling M, Jull G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J, Darnell R.

Physical and psychological factors predict outcome following whiplash injury.

PAIN 2005;114:141–8.Sterling M, Kenardy J, Jull G, Vicenzino B.

The development of psychological changes following whiplash injury.

PAIN 2003;106:481–9.Suissa S, Giroux M, Gervais M, Proulx P, Desbiens C, Delaney J.

Asessing a whiplash management model: a population-based non-randomized intervention study.

J Rheumatol 2006;33:581–7.Sullivan M, Adams A, Rhodenizer T, Stanish W.

A psychosocial risk factor targeted intervention for the prevention

of chronic pain and disability following whiplash injury.

Phys Ther 2006;86:8–18.Sullivan M, Bishop S, Pivik J.

The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation.

Psychol Assessm 1995;7:524–32.Sullivan MJL, Hyman M.

Return to work as a treatment objective for patients with chronic pain?

J Pain Relief 2014;3:1–3.Sullivan MJL, Stanish W, Sullivan ME, Tripp D.

Differential predictors of pain and disability in patients

with whiplash injuries.

Pain Res Manag 2002;7:68–74.Sullivan MJL, Tripp D, Santor D.

Gender differences in pain and pain behavior: the role of catastrophizing.

Cog Ther Res 2000;24:121–34.Verbeek J.

Return to work with back pain: balancing the benefits

of work against the efforts of being productive.

J Occup Environ Med 2014;71: 383–4.Vernon H, Mior S.

The Neck Disability Index: A Study of Reliability and Validity

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1991 (Sep); 14 (7): 409–415Carter JT, Birrell LN

Occupational Health Guidelines for the Management of Low Back Pain at Work

Occup Med (Lond) 2001; 51 (2): 124–135Wallman T, Wedel H, Johansson S, Rosengren A, Eriksson H, Welin L, Svardsudd K.

The prognosis for individuals on disability retirement.

An 18-year mortality follow-up study of 6887 men

and women sampled from the general population.

BMC Public Health 2006;6:103.Weiss D, Marmar C.

The impact of events scale—revised.

In: Wilson J, Keane T, editors.

Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD.

New York: Guilford, 1997. p. 399–411.Wideman TH, Sullivan MJ.

Differential predictors of the long-term levels of pain intensity,

work disability, healthcare use, andmedication use in a

sample of workers’ compensation claimants.

PAIN 2011;152: 376–83.Wideman TH, SullivanMJL.

Development of a cumulative psychosocial factor index for

problematic recovery following work-related musculoskeletal injuries.

Phys Ther 2012;92:58–68.Wlodyla-Demaille S, Poiraudeau S, Catanzarini J-F, Rannou F, Fermanian J, Revel M.

Translation and validation of 3 functional disability scales

for neck pain.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;83:376–82.Young AE.

Return towork following disabling occupational

injury–facilitators of employment continuation.

Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36: 473–83.

Return to WHIPLASH

Since 10-09-2022

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |