The Association Between a Lifetime History of

Low Back Injury in a Motor Vehicle Collision

and Future Low Back Pain: A Population-based

Cohort StudyThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: European Spine Journal 2018 (Jan); 27 (1): 136–144 ~ FULL TEXT

Paul S. Nolet, Vicki L. Kristman, Pierre Côté,

Linda J. Carroll, J. David Cassidy

Department of Graduate Education and Research,

Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College,

Toronto, ON, Canada.

pnolet@rogers.com

PURPOSE: This population-based cohort study investigated the association between a lifetime history of a low back injury in a motor vehicle collision (MVC) and future troublesome low back pain. Participants with a history of a low back injury in a motor vehicle collision who had recovered (no or mild low back pain) were compared to those without a history of injury. Current evidence from two cross-sectional and one prospective study suggests that individuals with a history of a low back injury in a MVC are more likely to experience future LBP. There is a need to test this association prospectively in population-based cohorts with adequate control of known confounders.

METHODS: We formed a cohort of 789 randomly sampled Saskatchewan adults with no or mild LBP. At baseline, participants were asked if they had ever injured their low back in a MVC. Six and 12 months later, participants were asked about the presence of troublesome LBP (grade II-IV) on the Chronic Pain Grade Questionnaire. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to estimate the association while controlling for known confounders.

RESULTS: The follow-up rate was 74.8% (590/789) at 6 months and 64.5% (509/789) at 12 months. There was a positive crude association between a history of low back injury in a MVC and the development of troublesome LBP over a 12-month period (HRR = 2.76; 95% CI 1.42-5.39). Controlling for arthritis reduced this association (HRR = 2.25; 95% CI 1.11-4.56). Adding confounders that may be on the casual pathway (baseline LBP, depression and HRQoL) to the multivariable model further reduced the association (HRR = 2.20; 95% CI 1.04-4.68).

CONCLUSION: Our analysis suggests that a history of low back injury in a MVC is a risk factor for developing future troublesome LBP. The consequences of a low back injury in a MVC can predispose individuals to experience recurrent episodes of low back pain.

KEYWORDS: Low back pain, Traffic accidents, Whiplash injuries, Risk factors, Cohort studies

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Globally, low back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of years lived with disability [1] and as a cause of disability adjusted life years (DALY) has gone from a rank of eleventh in 2000 to sixth place in 2010 [2]. LBP has a substantial economic burden with both direct and indirect costs [3]. In the general population, LBP is marked by a recurrent or persistent course [4]. Most LBP is mild and does not result in visits to primary care [5]. In those seeking primary care for LBP, one third had recovered by 12 weeks, and 65% reported LBP 1 year later [6]. Troublesome LBP can impact physical health related quality of life [7]. LBP has a point prevalence of 18.3%, 1-month period prevalence of 30.8% and 1-year period prevalence of 38% [8].

LBP is common after a motor vehicle collision (MVC). In patients reporting to emergency departments after a MVC, 37% reported moderate to severe low back pain 6 weeks later [9]. In a population-based cohort of Saskatchewan residents who reported being injured in a traffic accident, where they were treated or filed an auto insurance claim within 30 days, 60.4% reported LBP [10]. Subjects with LBP in this cohort were followed for 6 months. High pain intensity, female gender, full-time employment, concentration problems and early lawyer involvement delayed claim closure [11].

A question of importance to clinicians, insurers and governments is whether a history of a low back injury in a MVC will predispose subjects to experience future LBP and disability. Two cross-sectional studies found a positive association between a prior low back injury and current LBP [12, 13]. Cross-sectional studies are susceptible to issues of temporality, including prevalence/incidence bias and recall bias. A prospective study of insured drivers by Berglund et al. [14], found an increased risk of low back pain 7 years later in subjects with an injury in a rear-end collision compared to controls. They found no association 7 years later between those with no injury after a rear-end collision compared to controls. No prospective study of the general population has investigated the risk of future LBP due to a history of low back injury in a MVC. The purpose of this analysis was to test the association between a history of a low back injury in a MVC and future troublesome LBP in a general population sample while controlling for potential confounding factors.

Methods

Study design and source population

The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey (SHBPS), was a population-based 21-page mailed survey, on the distribution, determinants and risks of spinal disorders [15]. The Canadian province of Saskatchewan, during the time of the survey, had approximately one million inhabitants with universal health care coverage. Eligible for the study were Saskatchewan residents between the ages of 20 and 69 with a valid Health Services card on August 31, 1995. Excluded from the survey were inmates of correctional facilities, residents under the Office of the Public Trustee, foreign students and workers holding employment or immigration visas, and residents of special care homes [16].

Residents were selected from an age-stratified random sample from the Saskatchewan Health Insurance Registration File. The Health Insurance Registration File included more than 99% of the Saskatchewan residents. Subjects were randomly selected and sent the survey by Saskatchewan Health to protect the confidentiality of the participants. Participation in the survey was voluntary. The University of Saskatchewan Advisory Committee on Ethics in Human Experimentation approved the SHBPS and the current analysis was approved by the Lakehead University Research Ethics Board.

Study sample

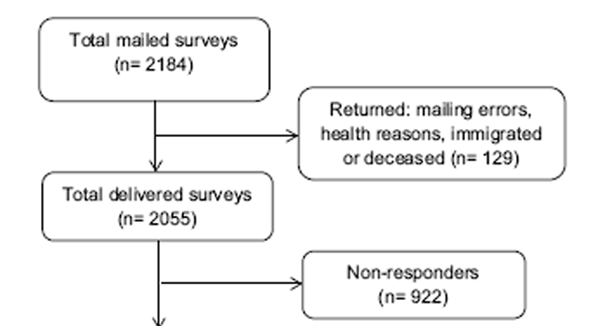

Figure 1 Eligible for the survey were 593,464 individuals of which 2,184 were randomly selected to receive the survey. One hundred and twenty-nine baseline questionnaires were returned due to mailing errors, ‘health reasons’, immigrated or died. Of the remaining 2,055 participants, 1,133 (55.1%) completed the baseline questionnaire. Twenty-one subjects did not complete the low back pain questionnaire and two subjects were outside of the pre-determined age range. Therefore, 1,110 subjects were eligible for this analysis (Figure 1). There were no important differences in age or gender between the eligible population and the randomly selected sample. However, a comparison of participants and nonparticipants found slightly more participation in older individuals, women and those who were married [17].

Data collection

The baseline survey was mailed in September 1995. The 6-month follow-up survey was sent to respondents of the baseline survey. The 12-month survey was sent to respondents of the 6-month survey.

Population at risk

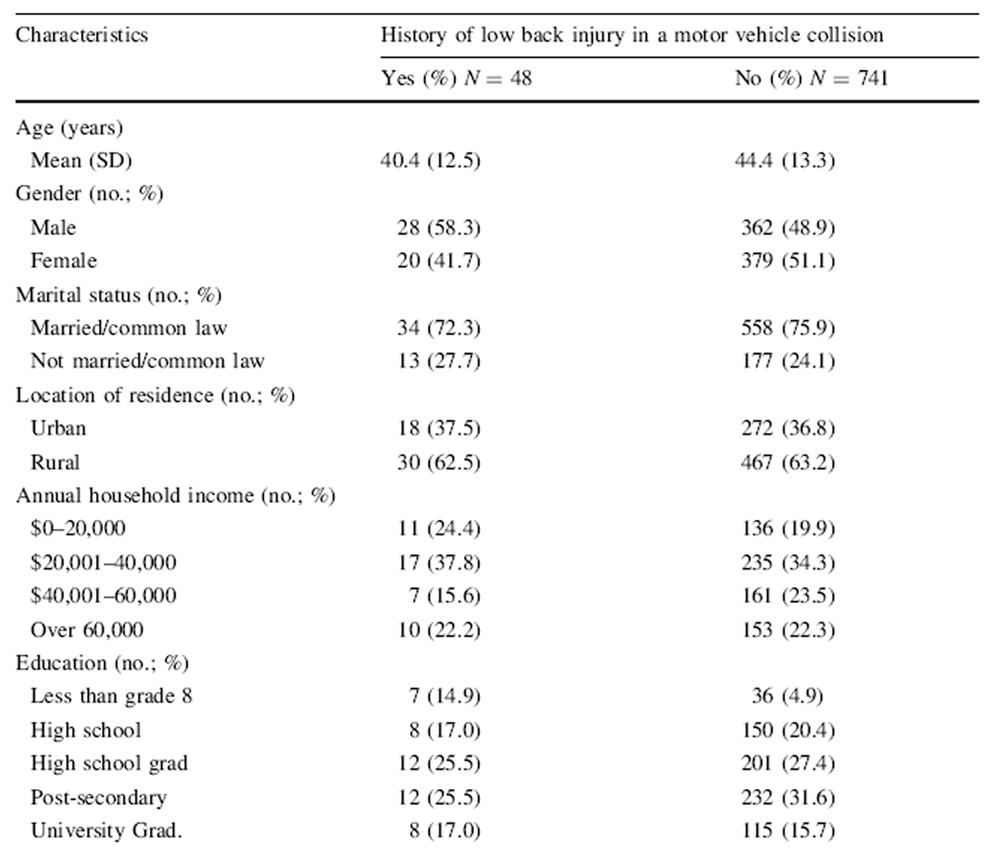

Table 1 The population at risk in this analysis consisted of individuals at baseline with no or mild low back pain (Grade 0 or Grade I) on the Chronic Pain Grade Questionnaire (CPQ) [17] (Table 1). Given that most individuals experience mild episodes of LBP annually, we included Grade I LBP in our population at risk of developing troublesome LBP.

Exposure

The main exposure was measured by asking participants: "Have you ever injured your low back in a motor vehicle accident?"

Outcome

Troublesome LBP was measured with the CPQ at 6 and 12 months. The questionnaire measures the 6-month period prevalence of LBP, LBP grades, and related disability, grading LBP into five ordered categories (Table 1). The questionnaire has good psychometric properties [17]. Participants with grades II, III or IV LBP were classified as having troublesome LBP.

The CPQ includes seven questions to grade LBP. Three questions used a numerical rating scale (0–10/10) to measure current, average (past 6 months), and worst LBP (past 6 months). One question asked about the number of days in the last 6 months that activity was limited due to LBP. Three questions asked about how much LBP has limited the ability to take part in recreational, social, and family activities; has limited daily activities; and the ability to work [17].

Potential confounders

Baseline grade 1 LBP may lie on the casual pathway between a history of low back injury in a MVC and the development of troublesome LBP (making it an intermediate variable). Alternatively, grade 1 LBP may increase the risk of troublesome LBP (potential confounding effects). The same may be true for HRQoL and depressive symptomatology. Misclassifying a factor as a confounder when it is in fact a mediator can introduce bias into the results. Thus, we developed two sets of potential confounders and analyzed the two sets separately. One set of potential confounders included the three factors that could be mediators, and the other set excluded these three factors. The following variables were considered as potential confounders of the association of interest.Socio-demographics Baseline gender, age, marital status, education level, income, employment status and location of residence.

HRQoL (SF-36) The Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 standard English- Canadian version 1.0 was used to measure self-perceived general health status [18]. The questionnaire assesses physical and mental HRQoL in eight domains. This analysis used the physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) of the SF-36. The physical component summary (PCS) includes physical functioning, bodily pain, role limitations due to physical health problems and general health domains. The mental component summary (MCS) includes role limitations due to emotional health, mental health, social functioning and vitality domains. The SF-36 has high internal consistency [19] and test–retest reliability [20]. It has a reliability estimate that usually exceeds 0.90 [21, 22].

Comorbidities Comorbidities and their self-perceived impact on health were measured with the Comorbidity Questionnaire. The questionnaire included questions about allergies, arthritis, cancer, digestive disorders, headaches, heart/circulation, high blood pressure, and kidney disorders. The self-perceived health impact of each comorbidity was rated on a four-point ordinal scale as: (1) not at all, (2) mild, (3) moderate and (4) severe. The Comorbidity Questionnaire has good test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.93) and adequate face, concurrent and convergent validity [23, 24].

Depressive symptomatology The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to measure depressive symptomatology [25]. The 20-item questionnaire asks about how often in the past week they have experienced symptoms of depression. Responses include 0 for rarely or none; 1 for some or little of the time; 2 for moderately or much of the time and 3 for most or almost all the time. The questionnaire is scored out of a possible score of 60 with 16 as the cut-off score for depression in the general population which has a sensitivity of 100% for major depression and a specificity of 88% [26]. The questionnaire has been shown to be reliable and valid in various populations with good internal consistency (alpha coefficients [0.85) [25, 27, 28]. The CES-D was used as a continuous variable in this analysis.

Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the sample were described stratified by exposure status. Loss to follow-up was examined for attrition bias by comparing baseline characteristics between responders and non-responders at 6- and 12-month follow-up using the Chi-square and t test.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to measure the association between a history of low back injury in a MVC and troublesome LBP. The modeling included three steps. First, a univariate model was built to estimate the crude association between our exposure and outcome. Second, a series of bivariate models were built to determine which variables led to a 10% change in the exposure regression coefficient. These variables were deemed to be confounders and included in the final model. Third, the final model included the exposure and all confounders identified in the second step [29]. IBM-SPSS version 22 was used for the analysis [30].

Variables deemed to be possible mediators on the causal pathway (depressive symptomatology, HRQoL and baseline LBP) were excluded in the first Cox model and included in a separate model if there was a 10% change in the exposure regression coefficient in the bivariate model.

Results

Sample characteristics

Our population at risk included 789 participants with baseline Grade 0 or I LBP. A history of a low back injury in a MVC was reported by 48 subjects (6.1%). Forty-five subjects reported troublesome LBP at 6 months and 39 at 12 months.

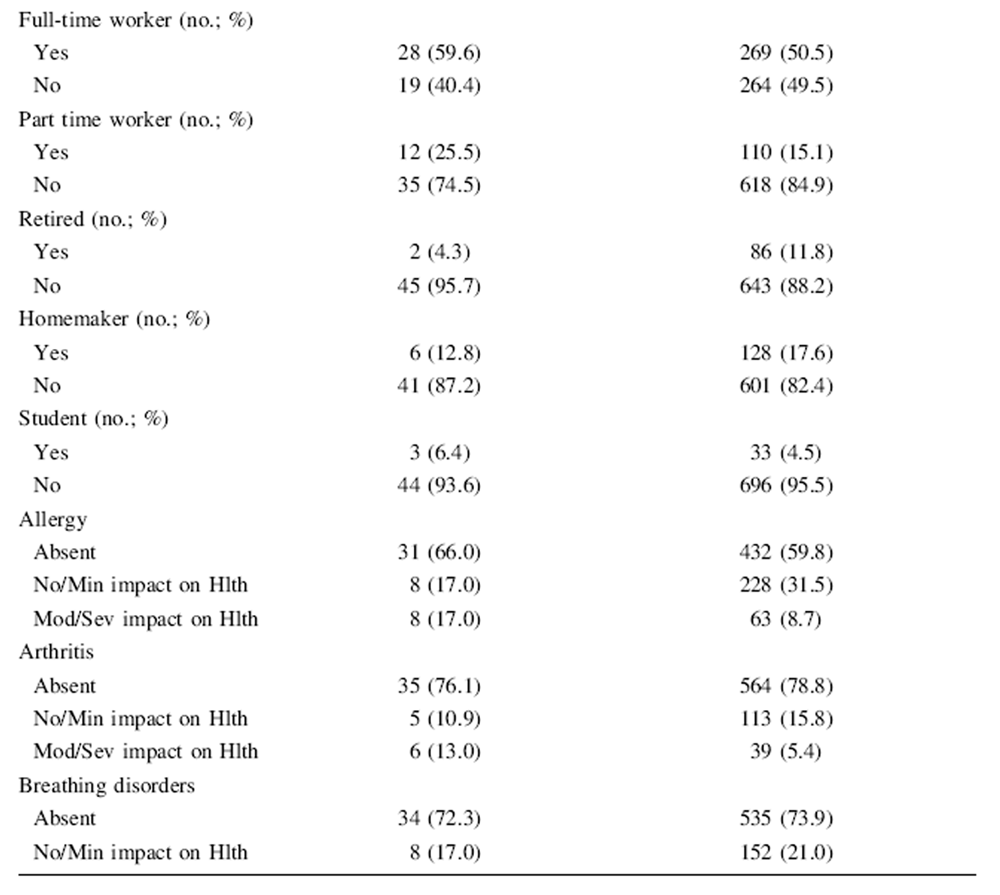

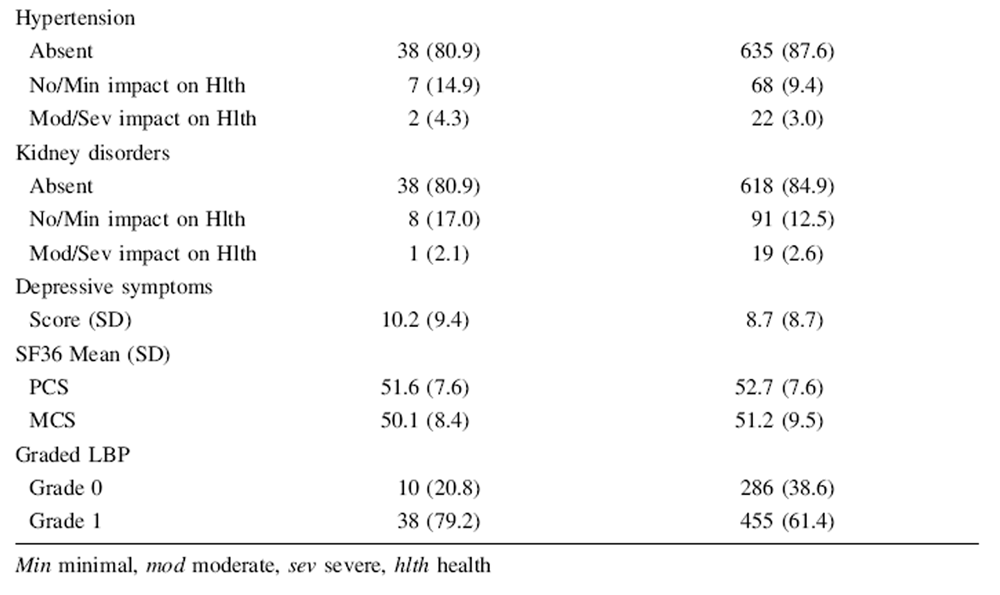

Participants with a history of low back injury in a MVC were younger, more likely to have grade I LBP and were less likely to have allergies that moderately to severely impacted their health (all at p\0.05) compared to those without a history of low back injury at baseline. Baseline HRQoL was similar between both groups (Table 2).

Attrition

The follow-up rate was 74.8% (590/789) at 6 months and 64.5% (509/789) at 12 months. Those completing the survey at 6 months were older and more likely to have higher levels of education and income (all at p\0.05) compared to those lost to follow-up at 6 months. Those followed at the 12-month survey were older and less likely to have cardiovascular problems that impacted their health, and more likely to have a higher income and higher education (all at p\0.05) than those lost to follow-up at 12 months. There was no statistically significant difference in baseline HRQoL scores grade between those followed and those lost to follow-up at either 6 or 12 months.

Association between a history of low back injury in a motor vehicle collision and troublesome LBP

We found a positive crude association between a history of low back injury in a MVC and the development of troublesome LBP over a 12-month period (HRR = 2.76; 95% CI 1.42–5.39). Adjusting for arthritis reduced the association (HRR = 2.25; 95% CI 1.11–4.56). Adjusting for covariates that may be mediators on the causal pathway (depressive symptomatology, HRQoL PCS and baseline graded LBP) along with arthritis further reduced this association (HRR = 2.20; 95% CI 1.04–4.68) (Table 3).

Table 2. Frequency distribution of the baseline demographic, socioeconomic, comorbidities

and health-related characteristics by exposure category

Table 2. Part A

Table 2. Part B

Table 2. Part C

Table 2. Part D

Discussion

Our survey was the first North American cohort study from the general population to prospectively investigate the association between a self-reported low back injury in a MVC (in those who had recovered to have no or mild low back pain) and the development of future troublesome LBP. Our results suggest that the incidence of troublesome LBP is higher in individuals who have had a past low back injury in a MVC compared to those who have not had a low back injury in a MVC.

Our findings confirmed the associations of prior crosssectional and prospective studies. A cross-sectional internet survey in Japan on 65,496 adults found a positive association between a traffic injury and chronic disabling low back pain (adjusted OR 2.81; 95% CI 2.07–3.81) [12]. In a cross-sectional study from the general population of Norway, 59,104 subjects responded to the whiplash question of the survey and of those 79.3% answered the questions on musculoskeletal symptoms [13]. After controlling for confounding factors there was a positive association between a history of a whiplash injury and low back pain in both males (adjusted OR 3.1; 95% CI 2.4–3.9) and females (adjusted OR 4.8; 95% CI 3.8–6.3) [13]. Cross-sectional studies cannot address the issue of causality, as LBP may have been present prior to the low back injury. Further, those with prevalent LBP may be more likely to recall a low back injury in a MVC. In a prospective study from a large insurance company in Sweden, subjects having had an injury in a rear-end collision (n = 242) were more likely to have LBP 7 years later compared to a group in similar collisions that did not complain of injury (age and gender adjusted RR 1.7; 95% CI 1.3–2.4). Subjects exposed to a rear-end collision without an injury were no more likely than an unexposed comparison group to have LBP 7 years later (age and gender adjusted RR 0.9; 95% CI 0.5–1.6).

Baseline LBP, depressive symptomatology and HRQoL were analyzed in a separate Cox proportional hazards model. Controlling for these covariates separately was to avoid over-adjustment by including covariates that may also be mediators on the casual pathway between a history of a low back injury in a MVC and the outcome, troublesome low back pain [32]. If these variables are on the casual pathway they should not be controlled for as confounders. In that case, including these variables as confounding variables would cause an under-estimation of the true association. In fact, controlling for these variables had little impact on the observed association. This had not been the case in a similar analysis from the SHBPS testing the association between a history of work-related low back injury and future troublesome low back pain gender (arthritis adjusted HRR = 2.24; 95% CI 1.05–2.77). When covariates that may also be mediators of the association (baseline LBP, depressive symptomatology and HRQoL) were added to the model, the effect estimate was attenuated (adjusted HRR = 1.37; 95% CI 0.82–2.29) [31].

The strengths to our study were the use of a large prospective, population-based random sample of Saskatchewan adults. Second, we used a valid and reliable questionnaire to measure LBP. Third, Cox proportional hazards modeling was used to control for confounding.

Our study also has limitations. The risk factors for future incident LBP, such as a low back injury in a MVC, may have a mediating effect on future pain and disability in those with a prior history of LBP. The population followed in this study excluded those with prevalent troublesome LBP which could reduce this risk of bias, but future studies need to test this hypothesis. Second, our analysis excluded those with troublesome LBP at baseline. This may have caused us to underestimate the true association as some of these subjects may have recovered from their LBP after a MVC, but may have developed a new incident episode of troublesome LBP prior to the baseline survey. Third, the exposure, a history of low back injury in a MVC could suffer from general misclassification although this is probably a minor issue as two previous studies have found that participants have a good recollection of a history of self-reported injury [33, 34]. Further, if misclassification of the exposure occurred, it would be non-differential in nature given the prospective study design. This would bias estimates towards the null, meaning the estimates of association calculated in this study were most likely conservative. Fourth, the attrition analysis suggested that estimates of the association were underestimated. Those lost to follow-up were younger and have lower levels of income and education than those continuing in the study, but did not differ in their baseline HRQoL. Finally, the baseline survey of the SHBPS had a 55% response rate. This may result in selection bias, but this was unlikely as the target population was similar to the actual population with respect to age group, gender and geographic location [35]. Further, in the wave analysis of the baseline survey the differences between response waves suggest no selective response bias due to LBP [35].

Our results inform the debate surrounding the etiology of LBP in the general population. Few studies have identified risk factors for recurrent episodes of LBP. This study supports prior research on the hypothesis that a past history of a low back injury in a MVC may be a determinant of future LBP. Our analysis provides the public, clinicians, government and insurers with evidence that a low back injury in a MVC may have a role in the development of future low back pain. The causal mechanisms linking a past history of low back injury in a MVC and future low back pain remains unknown, although it likely involves complex biopsychosocial relationships. These associations need to be examined in large cohort studies with careful attention to confounding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Chiropractors’ Association of Saskatchewan for funding the Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey and the assistance of Saskatchewan Health in sampling the Saskatchewan population. Dr. Kristman is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research through a New Investigator Award in Community-based Primary Health Care.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References:

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, et al.:

Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) for 1160 Sequelae of 289 Diseases and Injuries 1990-2010:

A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

Lancet. 2012 (Dec 15); 380 (9859): 2163–2196Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al.

Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010:

a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

Lancet 2013 Dec 15;380(9859):2197–223.Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F et al (2010)

Measuring the global burden of low back pain.

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 24:155–165Cassidy JD, Cote P, Carroll LJ, Kristman V (2005)

Incidence and course of low back pain episodes in the general population.

Spine 30(24):2817–2823Hayden JA, Dunn KM, van der Windt DA, Shaw WS (2010)

What is the prognosis of back pain?

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 24:167–179Itz CJ, Geurts JW, van Kleef M, Nelemans P.

Clinical Course of Non-specific Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort Studies Set in Primary Care

European Journal of Pain 2013 (Jan); 17 (1): 5–15Nolet PS, Kristman VL, Cote P, Carroll LJ, Hincapie C, Cassidy JD (2014)

Is low back pain associated with worse health–related quality of life six month later?

Eur Spine J 24(3):458–466Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P et al (2012)

A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain.

Arthritis Rheum 64(6):2028–2037Bortsov AV, Platts-Mills TF, Peak DA, Jones JS, Swor RA et al (2014)

Effect of pain location and duration on life function in the year after motor vehicle collision.

Pain 155:1836–1845Hincapie C, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Cote P, Guzman J (2010)

Whiplash injury is more than neck pain: a population-study of pain localization after traffic injury.

J Occup Environ Med 52(4):434–440Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Cote P, Berglund A, Nygren A (2003)

Low back pain after traffic collisions: a population-based cohort study.

Spine 28(10):1002–1009Fujii T, Matsudaira K (2013)

Prevalence of low back pain and factors associated with chronic disabling back pain in Japan.

Eur Spine J 22:432–438Myran R, Hagen K, Swebak S, Nygaard O, Zwart JA (2011)

Headache and musculoskeletal complaints among subjects with self-reported whiplash injury: the HUNT-2 study.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 12:129Berglund A, Alfredsson L, Jensen I, Cassidy JD, Nygren A ° (2001)

The association between exposure to a rear-end collision and future health complaints.

J Clin Epidemiol 54:851–856Nolet PS, Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ (2011)

The association between a lifetime history of a work-related neck injury and future neck pain: a population based cohort study.

J Manip Physiol Ther 34(6):348–355Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Cote P (2000)

The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey: the prevalence and factors associated with depressive symptomatology in Saskatchewan adults.

Can J Public Health 91:459–464von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF (1992)

Grading the severity of chronic pain.

Pain 50:133–149Ware JE Jr, Snow KK, Kosinski M et al (1993)

SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide.

The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, BostonBrazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L (1992)

Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care.

BMJ 305(6846):160–164Beaton DC, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C (1997)

Evaluating changes in health status: reliability and responsiveness of five generic health status measures in workers with musculoskeletal disorders.

J Clin Epidemiol 50(1):79–93Ware JE, Gandek B (1998)

Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project.

J Clin Epidemiol 51(11):903–912Ware JE (2000)

SF-36 health survey update.

Spine 25(24):3130–3139Nolet PS, Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ (2010)

The Association Between a Lifetime History of a Neck Injury in a Motor Vehicle Collision

and Future Neck Pain: A Population-based Cohort Study

European Spine Journal 2010 (Jun); 19 (6): 972–981Vermeulen S (2006)

Assessing the performance of a self-report comorbidity scale.

MSc Thesis, Unpublished manuscript, University of AlbertaRadloff LS (1997)

The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population.

Appl Psychol Meas 1:385–401Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Tilburg W (1997)

Criterion Validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older participants in The Netherlands.

Psychol Med 27(1):231–235Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, Myers JK (1982)

Screening for depression in a community sample.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 39(10):1195–2000Devins GM, Orme CM, Costello CG, Minik YM, Frizzell B, Stam HJ, Pullin WM (1988)

Measuring depressive symptoms in illness populations: psychiatric properties of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale.

Psychol Health 2:139–156Rothman KJ (2002)

Epidemiology, an introduction.

Oxford University Press, New YorkIBM Corp (2013)

Released IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. IBM Corp, ArmonkNolet PS, Kristman VL, Cote P, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD (2016)

The Association Between a Lifetime History of Low Back Injury in a Motor Vehicle Collision

and Future Low Back Pain: A Population-based Cohort Study

European Spine Journal 2018 (Jan); 27 (1): 136–144Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW (2009)

Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies.

Epidemiology 20:488–495Begg KJ, Langley JD, Williams SM (1999)

Validity of self reported crashes and injuries in a longitudinal study of young adults.

Injury Prev 5:142–144Pons-Villanueva J, Gegui-Gomez M (2010)

Validation of selfreported motor vehicle crash and related work leave in a multipurpose prospective cohort.

Int J Inj Control Saf Promot 17(4):223–230Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Cote P (1998)

The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey.

The Prevalence of Neck Pain and Related Disability in Saskatchewan Adults

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 (Aug 1); 23 (15): 1689–1698

Return to WHIPLASH

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Since 6-18-2017

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |