Fighting Injustice: A Historical Review of the

National Chiropractic Antitrust CommitteeThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Journal of Chiropractic Humanities 2019 (Dec 10); 26: 19–30 ~ FULL TEXT

Bart N. Green, DC, MSEd, PhD, and Claire D. Johnson, DC, MSEd, PhD

National University of Health Sciences,

Lombard, Illinois.

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this article is to provide a historical summary of the National Chiropractic Antitrust Committee (NCAC), a nonprofit organization that provided needed support for the Wilk et al v American Medical Association et al lawsuit, considered to be one of the most important legal cases in the history of the chiropractic profession.

METHODS: We reviewed journal articles, court documents, texts, interviews, and primary historical documents and created a chronology of events that was then synthesized into a factual account of the NCAC.

RESULTS: The primary function of the NCAC was to raise money to support legal steps necessary against actions of the nature of boycott, restraint of trade, or any acts deemed unlawful against the chiropractic profession. The NCAC eventually supported the Wilk et al v American Medical Association et al lawsuit, which ran from 1976 to 1990, consumed tremendous financial resources, and required significant efforts to raise funds from the chiropractic profession. The NCAC was also responsible for managing the distribution of reparations. Formed in 1975 and terminated after the trials, the NCAC played a vital role in supporting the trials and the post-trial distribution of funds for research.

CONCLUSION: The NCAC was successful in its mission to raise funds to support the 2 trials of the Wilk et al v AMA et al lawsuit, multiple appeals, and post-trial distribution of funds donated by the plaintiffs to support charity work for children and chiropractic research. Without the dedication of the NCAC staff and goodwill of the NCAC officers, it is likely that none of these benefits to the chiropractic profession would have been realized.

Key Indexing Terms Chiropractic, Antitrust Laws, Research

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Since the inception of the American Medical Association (AMA) in 1847, organized medicine in the United States hindered nonmedical providers when it established its Code of Medical Ethics. This code prohibited members of the AMA from consulting with or referring to any practitioner who came from a practice of health care not considered to be “regular.” [1] Thus, from the very beginning of chiropractic in the late 1800s, chiropractors faced opposition from organized medicine. However, during the 1950s through 1970s, chiropractors were aware of increased hostilities against them from the AMA, as evidenced in multiple publications of the period. [2–6] Ultimately, in 1964, leaders of the AMA formulated a Committee on Quackery with, “… its prime mission to be, first, the containment and, ultimately, the elimination of chiropractic.” [7]

The Committee on Quackery had a wide-ranging campaign against chiropractors. Its leadership distributed anti-chiropractic propaganda to medical doctors and medical students, influenced popular magazines and newspaper columns, and infiltrated other media. [8]The AMA implemented efforts to prevent the recognition of a chiropractic accrediting agency by the US Department of Education. [9] It also attempted to stop the inclusion of chiropractic in Medicare8 and produce position statements in opposition to chiropractic from major organizations such as the American Public Health Association, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, and the Association of American Medical Colleges. [10]

The chiropractic profession eventually responded to the increase in opposition. In the early 1970s, several chiropractors and chiropractic organizations began to consider what they might do to confront these pressing issues. Eventually, actions taken by individual chiropractors and chiropractic organizations culminated in a 17-year long series of trials, appeals, and post-trial negotiations known as the Wilk et al v AMA et al suit. [11]

For the efforts of the plaintiffs and their attorneys to be successful, a nonprofit organization was needed to serve as a foundation for the success of the litigation, to provide funding, and to disseminate any funds following the suit. The National Chiropractic Antitrust Committee (NCAC) was created for this purpose. The NCAC was established before the suit was filed and was a vital connection between the chiropractic profession and the plaintiffs during the long years of the trials.

The first trial was initially won by the AMA. [12] This decision was eventually overturned on appeal and the second trial was won by the plaintiffs. The primary argument was that the AMA had engaged in restraint of trade as an antitrust violation. [13]

Judge Susan Getzendanner’s final decision published in JAMA stated:The court has held that the conduct of the AMA and its members constituted a conspiracy in restraint of trade based on the following facts: the purpose of the boycott was to eliminate chiropractic; chiropractors are in competition with some medical physicians; the boycott had substantial anti-competitive effects; there were no pro-competitive effects of the boycott; and the plaintiffs were injured as a result of the conduct. These facts add up to a violation of the Sherman Act. [13]

The outcome of the trial would likely have been different if the NCAC had not existed. Up to this time, the story of NCAC has not been published. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to trace the history of the NCAC and discuss the importance of this organization to the success and outcome of the trials.

Methods

We reviewed journal articles, court documents, chiropractic texts, interview transcriptions, and other primary historical documents published from the 1950s through 1990s. We created a chronology of events that was then synthesized into a coherent factual account of the NCAC. Journal articles were mainly found in the American Chiropractic Association Journal of Chiropractic and the International Review of Chiropractic from January 1973 through 1992, which we searched by hand. Additional articles were found by searching the Index to Chiropractic Literature, which yielded articles authored by the plaintiffs and published in Dynamic Chiropractic in the early 1990s. We also searched the newspaper search engine Newspapers.com for relevant headlines. We searched the transcripts from the court trials from 1980 through 1990 using the search function of Adobe Acrobat in addition to hand searches. Finally, transcripts of interviews and personal correspondence were reviewed for information relevant to the NCAC.

Discussion

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, chiropractors had growing frustration with anti-chiropractic messages present in the media. Chester Wilk, DC, who practiced in the Chicago area, was driven to take action against these injustices. He began collecting documents that were anti-chiropractic in nature and studied them so that he could be prepared to speak against them. To improve his presentation skills, he took a communications course by Dr. Leonard Fay at the National College of Chiropractic, resulting in an improved and systematized communication approach. [14]

Figure 1 Chiropractic was not the only group that the AMA targeted. The AMA had also labeled the practices of Scientology as quackery. [15] As a reaction to this attack, the Church of Scientology planned and executed Operation Sore Throat against the AMA. During the operation, Scientology members infiltrated AMA headquarters and copied documents to expose various clandestine activities of the AMA that would damage the reputation of Scientology and undermine its political power in the United States. Selected documents from Operation Sore Throat were published in 1972 in a book titled In the Public Interest (Figure 1). [16] The book was published by the Church of Scientology [15] and the author was William Trever (likely a pen name). The contents were an indicting work of the AMA’s plan to eradicate chiropractic. [17] In addition to the publication of the book, more documents from AMA headquarters were leaked to newspaper reporters, government offices, and chiropractic officials by an anonymous source known as Sore Throat. [15]

By 1973, Wilk and other chiropractors had read In the Public Interest and were therefore aware of Operation Sore Throat and of Sore Throat the source (JF McAndrews, written communication, November 6, 1975). [18] At that time, Wilk published a book that discussed the trespasses that he felt were against chiropractic, and he began to expose questionable behaviors by organized medicine that discredited the chiropractic profession and other actions that violated the Sherman Antitrust Act (Wilk p. 97-99 [19]). In addition to selling his book, Wilk sold his tips for speaking via cassette tapes called the Chiropractic Speaker’s Bureau, which he promised would make listeners who used these techniques in-demand speakers on radio programs and at meetings. [20] In 1974, Wilk traveled to chiropractic conventions to promote his communications system. [14] He also encouraged chiropractors to join him in undertaking a lawsuit against the AMA. [14] Although he was charismatic, very few chiropractors offered to join him.

The Rallying of Allies and Birth of the NCAC

Figure 2

Figure 3

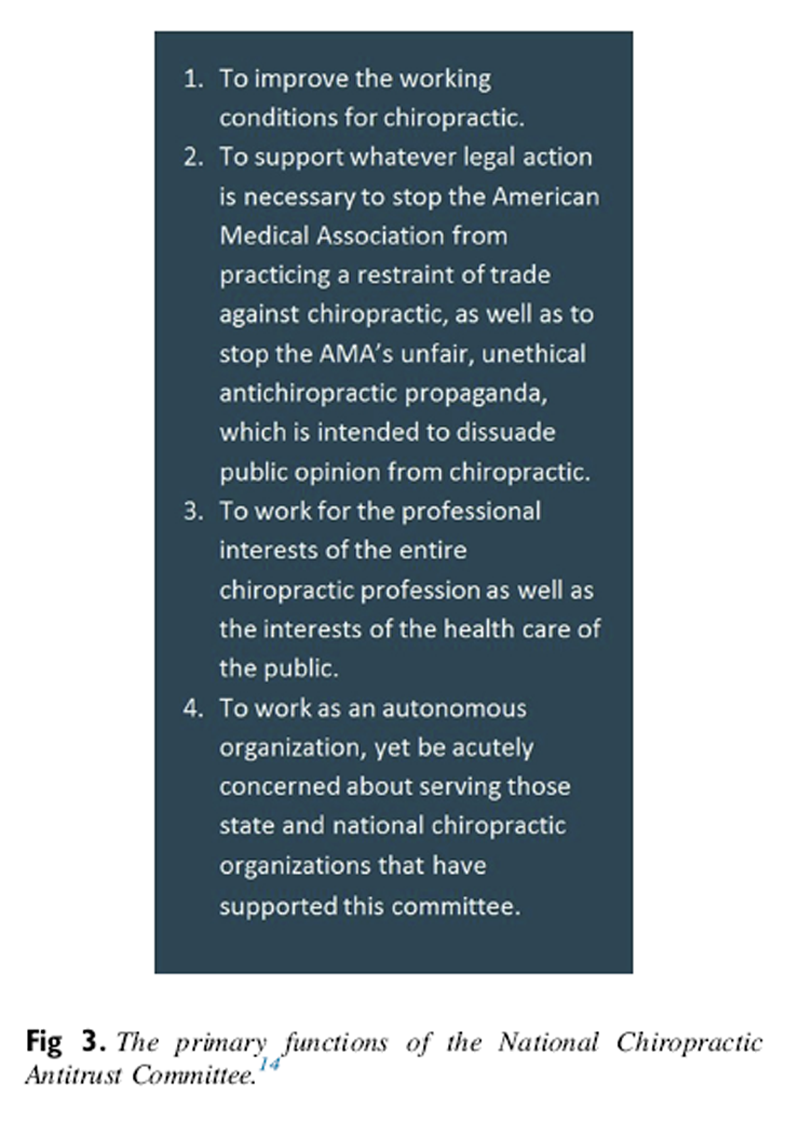

Figure 4 Wilk’s passionate pleas eventually resulted in the formation of an organization that would later provide support to a future antitrust suit. [21] On March 4, 1975, the NCAC became a tax-exempt nonprofit organization, approved by the Internal Revenue Service (EIN 23-7445239). [14] The first members were Collin Haynie, DC, of North Carolina; Michael Pedigo, DC, of California; Allen Unruh, DC, of South Dakota; and Clair O’Dell, DC, of Michigan (Figure 2). [22] Claire O’Dell served as the chairman of NCAC, Unruh as trustee, Haynie as treasurer, Wilk as secretary, and Pedigo as trustee and, later, co-chairman. [14, 21] All agreed that no members of the NCAC or plaintiffs were to receive any personal monetary compensation or damages for participation. The 4 primary functions of the NCAC as included in its October 17, 1974, charter are listed in Figure 3.

In the same year, stories of the leaked AMA documents were published in newspapers and magazines. [15] The New York Times reported in August 1975 that, “The documents, which were ‘leaked’ to several news organizations by an anonymous source in the last two months have been the basis of a number of embarrassing articles about the Chicago-based doctors association.” [23] Later, Time magazine reported, “As a result of Sore Throat’s leaks, Congressmen and Senators are talking of holding hearings on A.M.A. activities in order to determine whether they violate laws on political activities by corporations.” [24] These events being brought out into the open seemed to motivate others to take further steps at addressing the AMA issue.

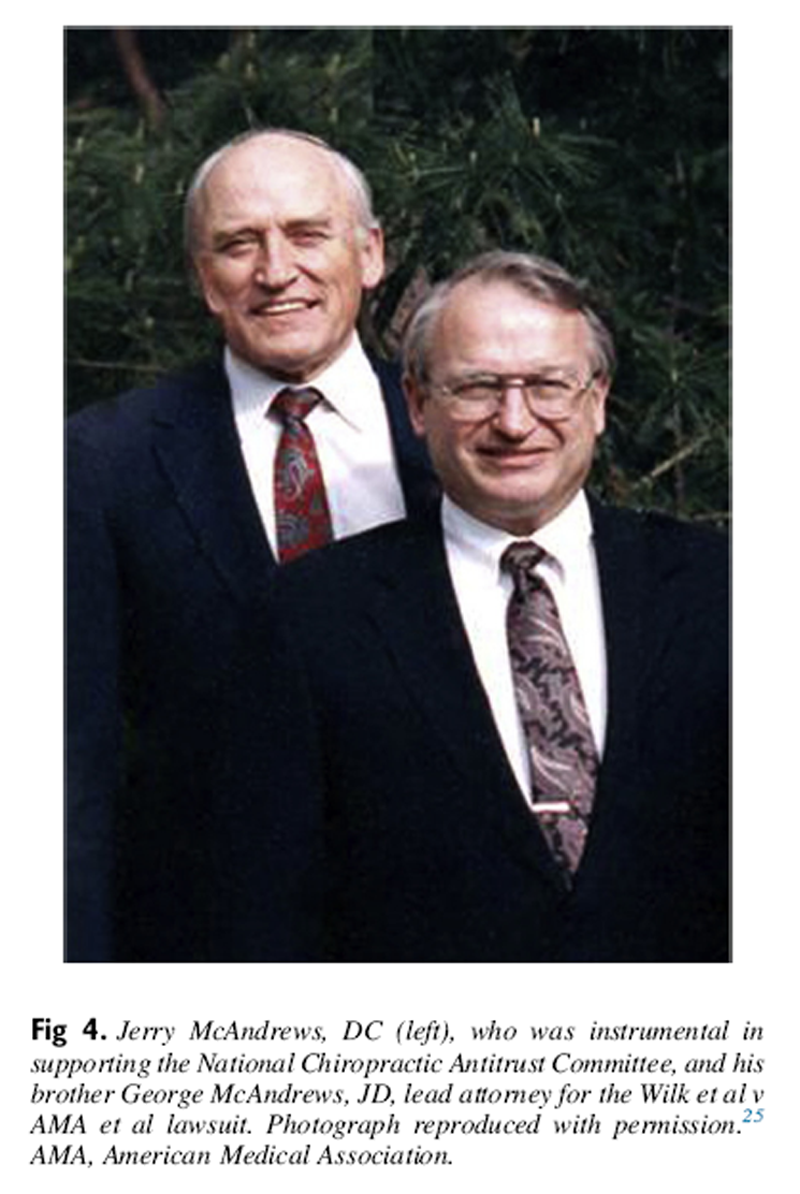

Jerry McAndrews, DC (Figure 4), executive director of the International Chiropractors Association (ICA), and other chiropractic leaders had received In the Public Interest and other leaked documents, including copies from the AMA’s anti-quackery chiropractic file that had been sent by Sore Throat. [18, 25] On October 29, 1975, The New York Times released an article revealing that, “The staff of the House Oversight, and Investigation subcommittee has concluded that the campaign of the American Medical Association to eliminate chiropractic service in the United States may violate the antitrust laws.” [26] The committee then sent the evidence to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for review “… wherein there was either a stated intent by the AMA to eliminate the chiropractic profession or plans were outlined to carry out that intent via harassment, delicensing and inducement of the boycotting of chiropractic services.” The ICA issued a press release confirming that it was aware of this new information. [27]

This stimulated interest from the profession. The American Chiropractic Association (ACA) and ICA received requests asking if they had legal action pending against the AMA and whether the press release had anything to do with Chester Wilk’s campaign. Jerry McAndrews (written communcation to Louis Sportelli, November 6, 1975) replied, “No, the action did not have anything to do with Dr. Wilk’s activities but rather harks back to the time when you’ll recall an anonymous source provided Dr. Flaum, among others, with copies of the AMA’s anti-quackery chiropractic file. Columnist Jack Anderson also received copies” (JF McAndrews, written communication, November 6, 1975).

Those at the ICA hoped that the FTC would conclude in favor of the chiropractic profession. If the FTC addressed the issue, it would spare the chiropractic profession from having to take legal action, which would be expensive and require many resources. Said Jerry McAndrews (written communication with Louis Sportelli, November 6, 1976), “Let’s hope that the FTC vigorously pursues the information given it by the Subcommittee. It could save all of us, including Dr. Wilk, a great deal of effort and perhaps heartache” (JF McAndrews, written communication, November 6, 1975). Unfortunately, the FTC did not act. “Of course the FTC did nothing with the committee’s conclusion. So it was left up to the profession to do something or not. Thus, after much effort, the Wilk case,” said Dr McAndrews (Written communication to Joseph Keating, Jr, March 13, 2006).

Figure 5 Shortly thereafter, on January 17, 1976, someone who claimed to be Sore Throat spoke by telephone to an audience at a Parker School of Professional Success seminar (Figure 5), which was reported to have 2,300 chiropractors and their staff in attendance. During the speech, Sore Throat stated that he spoke to raise funds for the NCAC lawsuit. He claimed that the AMA was in possession of records on the NCAC. He also claimed that he was in contact with Wilk and that the ACA and ICA had attorneys considering a possible antitrust case proposed by the NCAC. [14]

Sore Throat pressed the chiropractic profession to file suit against the AMA. He said that an antitrust suit would inhibit the AMA from destroying documents pertaining to a “secret organization” that involved the AMA, Better Business Bureau, FTC, United States Postal Service, and Food and Drug Administration. He stated that the organization, “… met secretly twice a year for the sole purpose of the elimination of drugless healing in the United States. Chiropractic, being the largest drugless healing body around was the most discussed subject especially by the AMA.” [28] He said that a private antitrust suit would show results faster than a FTC-led investigation and would lead to a faster injunction to preserve records.

He concluded [28]:Gentlemen – it will take a lawsuit. The AMA is not complacent and neither should you be.

One Hundred men, at a thousand dollars each are needed to make this suit a reality. Will these hundred men please step to the rear? It will be the best investment you ever made.At about this time, the NCAC officers asked attorney Paul Slater to review the evidence they had to form an opinion about whether the NCAC had a viable antitrust complaint against the AMA. [14] Wilk reported that Slater suggested the NCAC had a reasonable argument to take AMA to court for violation of antitrust laws. [14] Jerry McAndrews asked his brother, George McAndrews, who was an attorney in Chicago, to review similar documents for the potential evidence of a boycott by the AMA that might lead to a suit. [18]

By March 1976, the NCAC was announcing its activities to raise funds to file suit against the AMA. [29, 30] A July 1976 article published in the Quad-City Times read:Chiropractors planning a restraint of trade suit against the American Medical Association have raised about $90,000, Dr. J.F. McAndrews, executive director of the International Chiropractic Assn., said Monday.

The suit will be filed “at the earliest practical time” said Dr. Chester Wilk, secretary of the National Chiropractic Antitrust Committee, the group that intends to bring the suit. [31]Wilk approached the ICA board about his desire to file an antitrust suit against the AMA and to seek their endorsement. [14, 18] At a board meeting, a heated debate developed. During the arguments, the ICA lobbyist Joseph Adams encouraged the ICA officers to move toward supporting the suit. Jerry McAndrews, then an officer of the ICA, recalled that Adams said, [18]

I cannot believe I am hearing what I’m hearing. For as many years as I’ve worked with your organization, I have heard all kinds of bellyaching over the AMA attacks on your profession. Now you have someone who wants to push this matter to resolution and you’re debating it!? He’s not even asking for any money, just an endorsement. What the hell is the matter with you people?

Shortly after Adams’ comments, the board approved an endorsement, if there was approval from the ICA’s general counsel. [18] The general counsel did approve, resulting in the NCAC gaining the endorsement of the ICA. [18]

Wilk approached the ACA for endorsement. However, the ACA legal counsel and Washington lobbyist Harry Rosenfield was not supportive. Rosenfield’s opinion was that more could be accomplished through talking with the AMA rather than filing suit against it. [14, 32] As related by plaintiff Michael Pedigo (oral communication with Claire Johnson, February 11, 2010), the ACA, as advised by its counsel Harry Rosenfield, announced that it would not provide endorsement or support for an antitrust suit based upon political arguments. The ACA’s official stance on the issue appeared in its ACA Action Digest, reprinted in the September 1976 issue of the Texas Chiropractor [33]:Resolution No. 9

WHEREAS, the American Chiropractic Association (ACA) has the responsibility of overseeing chiropractic health care delivery, both to the profession and the public it serves; and WHEREAS, the ACA is convinced that the American Medical Association (AMA) has, is and will continue its covert and overt activities directed against chiropractic and the public it serves; and WHEREAS, the ACA believes that the accumulated evidence of these activities may be in violation of the law; further the ACA is actively encouraging appropriate government agencies to continue as well as to increase their investigation into the illegal activities of the AMA, therefore be it RESOLVED, that ACA in light of its present priorities, programs and commitments, cannot be supportive of private antitrust activities at this time; it does not discourage such activity nor does it discourage its members from participating as they deem appropriate. Contributions may be mailed to:

National Chiropractic Anti-Trust Committee

c/o P.O. Box 92666

Chicago, Illinois 60675Although the ACA did not endorse the lawsuit, it did allow the NCAC to broadcast information to ACA members through the ACA Journal of Chiropractic. The article read [34]:

AUTONOMOUS AND NON-PARTISAN. Not under control of any state of national chiropractic organization, though it cooperates with all chiropractic organizations in an effort to best represent the ENTIRE chiropractic profession. Its committee members are from all factions in chiropractic, and recognize that partisan chiropractic has NO RELEVANCE in this committee and its objectives.

The lack of interest and support from the ACA must have been a disappointment to the NCAC officers. Yet, the NCAC members continued to move ahead with the support that was available.

By November 1976, a NCAC fact sheet cried out,

“Organized medicine is perpetuating a vicious and cruel restraint against chiropractic and the unsuspecting public. It is most appropriate that on the bicentennial anniversary of the nation’s revolution, we unite to stop another kind of tyranny and oppression.”[35]

A small group of chiropractors had stepped forward as plaintiffs, and a lead attorney had been retained. The plaintiffs who completed the trial were Chester A. Wilk, DC; James W. Bryden, DC; Patricia B. Arthur, DC; and Michael D. Pedigo, DC. The lead attorney was George McAndrews, the brother of Jerry McAndrews. The plaintiffs filed suit on October 12, 1976, in the Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division.

The complaint was as follows:Commencing at least as early as November, 1963, and continuing through the present, defendants and their con-conspirators have been and are engaged in a combination, conspiracy, and continuing course of conduct having as its objective first the isolation and then the elimination of the profession of chiropractic through, inter alia, unreasonable restraints on the rights of the individual members of the defendant trade associations to establish and carry on inter-professional relations with members of the chiropractic profession including the plaintiffs herein and enforcement of a concerted refusal by defendants and those acting in concert therewith to deal with plaintiffs and other members of the chiropractic profession. [36]

The defendants were

the AMA,

the American Hospital Association,

the American College of Surgeons,

the American College of Physicians,

the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals,

the American College of Radiology,

the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons,

the Illinois State Medical Society,

the Chicago Medical Society,

H. Doyl Taylor,

Dr. Joseph A. Sabatier,

Dr. H. Thomas Ballantine, and

Dr. James H. Sammons.Thus, the chiropractors filed an antitrust suit against 9 of the most prestigious medical organizations in the United States and 3 former officers of the AMA. [11] Certainly, the many years to follow would be costly.

During the Trials

The plaintiffs and contacts provided the early monies to fund the lawsuit. As news about the case spread, many other chiropractors realized that the outcome of the case could significantly determine the future of the profession. Thus, the NCAC started to receive more donations.

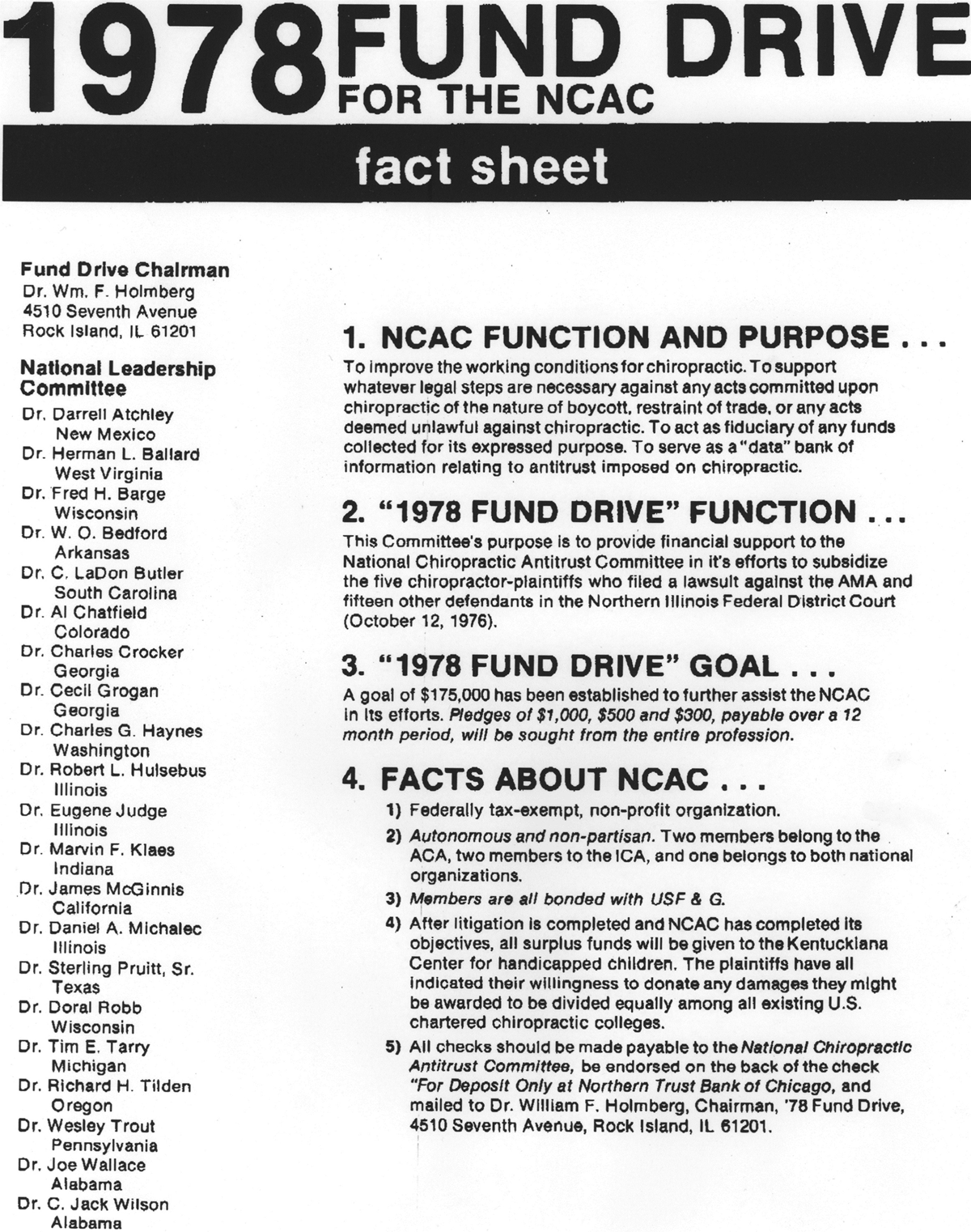

Figure 6 Jerry McAndrews asked William Holmberg, DC (Figure 6), of Illinois to lead a funding drive committee for the NCAC. Holmberg had experience in that he was a longtime supporter of Palmer College and had managed a number of fundraising campaigns for the institution. The ICA offered to provide the clerical and secretarial support that Holmberg needed to properly execute the campaign and with the ICA headquarters being located at the nearby Palmer College, Holmberg agreed to volunteer. Thereafter, Holmberg became the fundraiser for the Antitrust Fund Raising Committee and later was voted as trustee. The NCAC then started collecting funds to support the antitrust lawsuit.

Unfortunately for Holmberg, the next year the ICA moved its headquarters to Washington, DC, [37] and he no longer had the support he needed. Holmberg’s office receptionist and her sister-in-law stepped up to fill the void and were paid part-time salaries by the ICA until the fundraising committee could receive enough funds to pay the staff directly. [38]

Figure 7 Soon after Jerry McAndrew’s request for him to head the fundraising committee, Holmberg set up a national fundraising committee with 21 chiropractors serving as members (Figure 7). [39] The NCAC leaders began the onerous task of trying to raise $175,000 in 6 months. The ICA held rallies at ICA conventions and appeals were made to the ICA leadership and representatives. The president of the ICA, Joseph Mazzarelli, and Jerry McAndrews “… traveled about 75,000 miles a year for 5 years raising funds to support the law suit.” [18] The chairman of the NCAC, Clair O’Dell, also traveled across 12 states to tell chiropractors of the importance of the lawsuit and to raise funds. [40] Despite the organized group funding efforts, Holmberg found that the most effective way to raise money was to make personal contact with donors, rather than counting on organizations to contribute.

Money was coming in to the NCAC, but the amount was not reaching the necessary goal. Holmberg perceived that a substantial problem was that the ICA was the only supporting organization and that the suit and its funding drive had to have the support of the ACA and its affiliated state associations. Until the ACA House of Delegates and Board of Governors finally approved supporting the suit, funds were extremely limited.

Holmberg launched and maintained a daunting public relations, marketing, and information campaign to distribute the message that the suit needed financial backing from the profession. He and his staff sent updates, funding requests, and information to as many chiropractic publications as they could reach. The NCAC fund-raising committee contacted state associations, which were asked to support the cause, as were chiropractic college officials. Chiropractic students provided a tremendous boost to the campaign by increasing the awareness of the campaign with their field chiropractors. Even the vendors to the profession were approached to support the profession that supported them.

Figure 8 Three years after the lawsuit was filed and a year before the first trial began, the ACA finally agreed to support the Wilk et al v AMA et al trial after receiving increasing pressure from NCAC and ACA membership. In November 1979, the ACA Journal of Chiropractic ran a full-page advertisement for support of the NCAC (Figure 8) with endorsement by Harry Rosenfield, the same legal counsel who advised the ACA not to support the trial since 1976. [41]

The ad was dubbed “It is Now the 11th Hour.”It is not a secret that originally I was not in favor of a single national antitrust suit but preferred a series of state suits, some to be brought by Attorneys General of various states.

As it has turned out both approaches have been followed. And this has been good, each approach strengthening the other. Time has shown that, at least to this point, the key case has been the lawsuit brought by Dr Chester Wilk and four other DCs in Chicago. Such litigation is very expensive, and the Wilk Case is desperately in need of funds.

The AMA can pour virtually limitless funds into the defense of its bitterly anti-chiropractic position. Now is the time for DCs to stand up for their profession with their bucks as well as their mouths by supporting the National Chiropractic Antitrust Committee (NCAC).Holmberg’s staff and committee primarily used mail to reach potential donors. Now that both organizations confirmed their support, the ACA and ICA jointly made appeals to the profession to pledge using joint stationery signed by the respective presidents. According to Holmberg, the NCAC fundraising committee sent out 20 to 30 of these joint requests. Collective unity seemed to strike a chord with chiropractors. Holmberg recalled, “When the profession saw that for one of the few times in the history of organized chiropractic the ACA, ICA, colleges and state associations were finally working together on a joint venture, the money and pledges began to come in.”38 Contributions from chiropractors who were not members of either the ACA or ICA were the largest, as there were more of them than ICA and ACA members. Holmberg, his staff, and the committee frequently received replies thanking the ICA and ACA for their joint ventures.

Contributions came from all sorts of chiropractic constituents. George McAndrews spoke throughout the country and was provided an honorarium of $1000 and travel expenses for his presentations; however, he never kept the money. Holmberg recalled, “George sent each $1,000 check to me. He contributed thousands of dollars himself.” [38] Holmberg recalled that the largest donation was from the ACA for $50,000 after it decided to support the lawsuit. [38] The smallest donation was $1 from a chiropractic student. In the note that came with the dollar, he said that he wished he could have donated more but was under financial hardship. Holmberg recalled that the most unusual donation was received was submitted in a plain paper bag. A bond was attached to a piece of cardboard with a note that said, “Funny what you can find in brown bags – do not call me or contact me.”

Holmberg said, [38]Enclosed was a bearer bond …. Wow, what a shock!! As you know a bearer bond can be cashed by the person who has it in his possession. No name or owner is designated on the bond. I immediately called a stock broker and asked what I should do. He said, “Cover it up, hold on to it and bring it to me immediately.” We redeemed the bond for $6,000 (including accrued interest).

The lawsuit had been filed in October 1976 and 4 years would elapse before the first trial began, which lasted nearly 2 months. On January 29, 1981, the case was lost. The jury gave a verdict that the defendants had not violated antitrust law. The decision was appealed, the appeal was granted, and the case went to court again on April 22, 1987. [42]

On September 25, 1987, the judge’s decision of the second trial was that, “the American Medical Association (‘AMA’) and its members participated in a conspiracy against chiropractors in violation of the nation’s antitrust laws.” [13] This decision was upheld by the US Court of Appeals on February 7, 1990. The AMA petitioned the decision with the US Supreme Court 3 times, but the petitions were denied. The suit was finally settled with the final denial on November 26, 1990. [43]

Another 2 years would pass in negotiations about reparations the AMA would make to cover the legal costs of the plaintiffs. This process required more funds to pay for the expenses associated with these activities. In one of his final requests to the chiropractic profession to donate money to the cause, Holmberg said that changes were… unlikely to be adopted by the AMA without long, drawn out legal maneuverings. It would be a travesty of justice to abandon the ‘Chicago Four’ plaintiffs (Drs. Wilk, Pedigo, Arthur, and Bryden) at this critical juncture of the lawsuit; and to allow the AMA a token compliance of the court’s order of injunction, due to a lack of financial resources necessary to pursue the case to its justified conclusion. [44]

From the beginning of the NCAC to the end of negotiations, 17 years had passed. It had been an exhausting experience for all parties. The fundraising efforts were noteworthy and Holmberg concluded, “It was a long battle and one of the toughest fund raising experiences I have ever had. But believe me, it was worth all the time and effort to serve the profession.” [38]

After the Trials

After the trials and negotiations over reparations, the AMA agreed to pay $3.5 million. [45] From this amount, first, the legal fees were paid. Then, settlements that would have gone to the plaintiffs were turned over to the profession since the plaintiffs went into the second trial stating that they did not desire to receive a settlement personally. Thus, the final function of the NCAC was to decide the recipients of funds. The NCAC members and officers agreed that the money should be donated to fund chiropractic research and the Kentuckiana Children’s Center. The Kentuckiana Children’s Center was a nonprofit collaborative care facility for children with special needs. [46]

The funds for research were to be sent to accredited chiropractic colleges and chiropractic research initiatives. [44] As stated by Michael Pedigo, “The plaintiffs did not receive any financial gain. The entire financial portion of the settlement was transferred to the NCAC, which will have the responsibility to pay any outstanding legal fees. The remaining funds will be used to advance the chiropractic profession.” [21] As was stated in the NCAC charter, any “damages, awards from litigation will be divided equally between all existing chartered chiropractic colleges in America.” [47]

At the time, there were 17 chiropractic colleges that would receive these funds. However, exactly how these monies would be spent by each chiropractic college was not stipulated in the charter.

Wilk recalled:The plaintiffs and the NCAC made an appeal to all 17 chiropractic colleges to donate each of their award shares into ONE fund to be used for somatovisceral controlled symptom-related outcome studies. Ten of the chiropractic colleges initially agreed to this proposal, and an 11th college indicated it would follow suit. The other colleges, for varying reasons, chose to keep their share of the settlement for themselves. [47]

The joint fund was the Consortium for Chiropractic Research (CCR). The CCR was started in 1985 as the Pacific Consortium for Chiropractic Research. [48, 49] The Pacific Consortium for Chiropractic Research evolved during the latter part of the 1980s to organize research efforts of the chiropractic colleges on the West Coast and to foster collaboration and the sharing of resources among the colleges. The PCCR included Palmer College of Chiropractic West, Western States Chiropractic College, Life Chiropractic College West, Cleveland Chiropractic College - Los Angeles, and the Los Angeles College of Chiropractic. [49]

As more colleges desired to become part of the Pacific Consortium, the Pacific Consortium became a national consortium as the CCR. [50] Financial support for the CCR came from the California Chiropractic Foundation and the Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research, in addition to contributions from CCR member colleges. Bolstered by joint support from the ACA, the ICA, and several state chiropractic associations, the CCR dedicated more than 85% of its funds directly to research. Part of the CCR directive was that all research proposal applications for funding had to be a collaboration between 2 or more colleges. The CCR use a competitive peer review process to evaluate the proposals and to guide the selection of grants. [48]

It was to this Consortium that the plaintiffs and the NCAC hoped the colleges would direct their awards from the lawsuit.

They reported,“It was reasoned that if the colleges could pool their experience and resources, and eliminate duplication and waste, that collectively we could make greater strides in research. This is the purpose of the Consortium for Chiropractic Research.” [48]

The job of distributing the funds to the Consortium and its member colleges was assumed by the Association of Chiropractic Colleges (ACC), with certain stipulations that were as follows [47, 51]:

Funds shall be available for consortium projects but limited to those chiropractic colleges who have contributed to the pooled funds,

Funds should be directed towards efficacy and efficiency studies of chiropractic care,

Funds shall be directed into areas other than low-back research, with special consideration towards somata-visceral relationships, and

The ACC shall receive an annual detailed written report giving a full accounting of all expenditures of funds, progress of current activities and copies of all publications, reports, etc.

The ACC shall retain all rights of ownership, patents, inventions, etc. derived from the use of the funds.

The ACC shall be acknowledged in all publications, presentations and other forms of communications for the support given.

However, not all of the 17 colleges that received funds from the suit participated in this collegial effort. [47, 48] For example, Sherman College of Straight Chiropractic sued the NCAC for not receiving funds that its leaders felt were owed to the college. [52]

Regardless, the financial contributions made to the CCR out of the generosity of the plaintiffs were noteworthy for supporting research endeavors of the members of the CCR (William C. Meeker, written communication with Bart Green, August 14, 2019). By 1996, the funds from the trial had been used up for research and the CCR ceased to exist in its consortial form. In 1996, the CCR ended and was converted to the American Spinal Research Foundation, with the sole purpose being to raise funds for spine research. [53]

It is unknown exactly when the NCAC concluded operations, but it seems it was around 1996, since that is when the funds were exhausted. The NCAC’s 501(c)(3) status was automatically revoked by the Internal Revenue Service in May 2010 since the organization had not filed an Internal Revenue Service form 990 since 2007 (https://apps.irs.gov/app/eos/).

The NCAC served its noble purpose and faded from the view of the profession. However, without its presence, the mechanisms would not have been in place to allow for a successful outcome of the Wilk et al v AMA et al. The chiropractic profession has transformed into what it is today, in part owing to the efforts of all those involved with the NCAC.

Throughout these events, the profession seemed to be stronger when the factions joined together to fight a common enemy. The officers of the NCAC did a superb job of navigating these difficult intraprofessional political waters for nearly 2 decades. Ultimately, modern-day chiropractors should be grateful to those men and women who participated in and donated to the NCAC. They helped to break down the barriers once created by the AMA so that we now can practice without restraint to serve the public.

Limitations

There are limitations to this research. Surviving documents about the NCAC are scarce. There may be relevant papers or artifacts that were inadvertently missed. Our interpretation of the events related to the NCAC is limited to the materials available. Some of our sources were interviews, manuscripts, or letters where the author recalled past events. Recall bias is an issue when referencing interview sources.

Conclusion

The NCAC was successful in its mission to raise funds to support the Wilk et al v AMA et al lawsuit, 2 trials, multiple appeals, and post-trial distribution of funds donated by the plaintiffs to support charity work for children and to provide funding for chiropractic research. Without the dedication of the NCAC staff and goodwill of the NCAC officers, it is doubtful that these benefits to the chiropractic profession would have been accomplished.

Practical Applications

The NCAC succeeded in raising funds for the Wilk et al v AMA et al lawsuit and post-trial distribution of funds donated by the plaintiffs to support charity work for children and to provide funding for chiropractic research.

Without the NCAC, it is possible that the chiropractic profession would have not progressed as much as it did and may not have won the lawsuit.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): B.N.G., C.D.J.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): B.N.G., C.D.J.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): B.N.G.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): B.N.G., C.D.J.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): B.N.G., C.D.J.

Literature search (performed the literature search): B.N.G., C.D.J.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): B.N.G., C.D.J.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): B.N.G., C.D.J.

References:

American Medical Association

Code of Medical Ethics of the American Medical Association

American Medical Association, Philadelphia, PA (1847)L.M. Rogers

Editorial

J Natl Chiropr Assoc, 32 (1) (1962)

5,64,65Iowa MDs read the riot act

Int Rev Chiropr, 12 (7) (1958), pp. 12-13The Yale article: AMA monopoly scored

Int Rev Chiropr, 9 (4) (1954)

3,35-36E.J. Murphy

A report on the National Congress on Medical Quackery

J Natl Chiropr Assoc, 31 (11) (1961)

13,14,56L.M. Rogers

Editorial

J National Chiropr Assoc., 31 (11) (1961)

5, 54, 56Wilk v AMA, 76 C 3777 (ND IM December 12, 1980).

W.I. Wardwell

Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession

Mosby-Year Book, St. Louis, MO (1992)O. Hidde

Historical perspective: the Council on Chiropractic Education and the Committee on Accreditation, 1961-1980

Chiropr Hist, 25 (1) (2005), pp. 49-77Wilk v AMA, 76 C 3777 (ND IM January 26, 1981).

Wilk v AMA, 76 C 3777 (ND IM December 8, 1980).

D.J. Lawrence

Wilk v. American Medical Association, 895 F. 2d 352 (7th Cir. 1990): the battle is not yet won

Chiropr Hist, 30 (2) (2010), pp. 41-47S. Getzendanner

Permanent injunction order against AMA

JAMA, 259 (1) (1988), pp. 81-82C.A. Wilk

Medicine, Monopolies, and Malice

Avery Pub. Group, Garden City Park, NY (1996)United States of America v Jane Kember and Morris Budlong,

78-401(2)&(3) (D.C. Cir. December 16, 1980).W. Trever

In the Public Interest

Scriptures Unlimited, Los Angeles, CA (1972)W. Good

AMA plot is exposed in new book

The Gettysburg Times (June 5, 1973), p. 3J. McAndrews

Past, Present and Future. Reflections on Presentation at Chiropractic Centennial, 1995 (1997)C.A. Wilk

Chiropractic Speaks Out; A Reply to Medical Propaganda, Bigotry, and Ignorance

Wilk Pub. Co., Park Ridge, Illinois (1973)C. Wilk

Advertisement

Am Chiropr Assoc J Chiropr, 10 (1976), p. 58M. Pedigo

Perspectives of a plaintiff

Dynamic Chiropr, 10 (6) (1992)

https://www.dynamicchiropractic.com/mpacms/dc/article.php?id=43145Photograph of initial officers of the NCAC

Digest Chiropr Econ, 19 (2) (1976), p. 42D. Burnham

4 AMA employees quizzed on leak

The New York Times (Aug 6, 1975)Medicine

Sore throat attacks

Time, 106 (Aug 18) (1975), p. 52S. Haldeman, G.P. McAndrews, C. Goertz, L. Sportelli, A.W. Hamm, C. Johnson

The McAndrews Leadership Lecture: February 2015, by Dr Scott Haldeman

Challenges of the Past, Challenges of the Present

J Chiropractic Humanities 2015 (Nov 18); 22 (1): 30–46D. Burnham

AMA criticized on chiropractic

The New York Times (Oct 29, 1975)For immediate release [press release]

International Chiropractors Association, Davenport, IA (October 29, 1975)Sore Throat.

Parker speech. January 17, 1976.J. Ney

Chiropractors plan to sue AMA; trade restraint

The Des Moines Register (March 23, 1976), p. 1C. Thompson

Chiropractors plan action AMA faces suit

Quad-City Times (March 23, 1976), p. 12C. Thompson

Chiros raise funds for suit

Quad-City Times (July 20, 1976), p. 19C. Johnson, B. Green

Interview with George McAndrews and Louis Sportelli

(July 16, 2010)Resolution No. 9

Texas Chiropractor, 33 (9) (1976), p. 31National Chiropractic Antitrust Committee

Fact sheet of NCAC

Am Chiropr Assoc J Chiropr, 13 (10) (1976), pp. 33-34National Chiropractic Antitrust Committee

Support the National Chiropractic Antitrust Committee

Am Chiropr Assoc J Chiropr, 13 (11) (1976), p. 61Wilk v AMA complaint

(ND IM October 12, 1976).ICA home office plans vital move to Washington, DC

Int Rev Chiropr, 32 (3) (1978), pp. 28-29Holmberg W.

Recollections of the Wilk et al v. AMA et al suit to Joseph C. Keating, Jr. June 4, 2007.Dr William Holmberg kicks off ’78 fund drive for NCAC

Int Rev Chiropr, 32 (2) (1978), p. 6C.W. O’Dell

NCAC chairman writes open letter to the profession

Int Rev Chiropr, 32 (2) (1978), p. 8H. Rosenfield

It is now the 11th hour

Am Chiropr Assoc J Chiropr, 17 (11) (1979), p. 4Wilk v AMA No. 76 C 3777

(ND IM April 22 1987).M. Pedigo

Wilk vs AMA: was it worth the fight?

Dynamic Chiropr, 16 (15) (1998)

https://www.dynamicchiropractic.com/mpacms/dc/article.php?id=37334W. Holmberg

Funding the last phase of the Wilk et al. v. AMA suit

Dynamic Chiropr, 9 (5) (1991)

https://www.dynamicchiropractic.com/mpacms/dc/article.php?id=44166H. Wolinsky, T. Brune

The Serpent on the Staff: The Unhealthy Politics of the American Medical Association

G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, NY (1994)T. Barnes

Kentuckiana Children’s Center: a 40-year history

J Chiropr Humanit, 7 (1997), pp. 18-22C.A. Wilk

Major research on tap for chiropractic in 1993

Dynamic Chiropr, 11 (4) (1993)

http://www.dynamicchiropractic.com/mpacms/dc/article.php?id=42083P. Arthur, J. Bryden, C. Haynie, et al.

Wilk plaintiffs speak out: from litigation to research - new direction for the ’90s

Dynamic Chiropr, 11 (8) (1993)J.C. Keating

Toward a Philosophy of the Science of Chiropractic: A Primer for Clinicians

Stockton Foundation for Chiropractic Research, Stockton, CA (1992)J.C. Keating, R.B. Phillips

A History of Los Angeles College of Chiropractic

Southern California University of Health Sciences, Whittier, CA (2001)C.A. Wilk

Anti-trust case award settlement

Am Chiropr Assoc J Chiropr, 30 (2) (1993), pp. 19-20A.L. Mauldin

College files suit to recover funding

The Greenville News (July 25, 1995), p. 10D.C. Cherkin, R.D. Mootz, United States Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (Eds.),

Chiropractic in the United States: Training, Practice, and Research

U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services,

Public Health Service,

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research,

Rockville, MD (1997)

Return to the WILK Section

Since 12-29-2019

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |