Complementary and Alternative Medicine

in a Military Primary Care Clinic:

A 5-year Cohort StudyThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Military Medicine 2011 (Jun); 176 (6): 685–688 ~ FULL TEXT

MAJ Susan George , MC USA ; COL Jeffrey L. Jackson , MC USA (Ret.); Mark Passamonti , MD

Department of Medicine,

Walter Reed Army Medical Center,

6900 Georgia Avenue NW,

Washington, DC 20307, USA.Previous studies have found that complementary and alternative medication (CAM) use is common. We enrolled 500 adults presenting to a primary care military clinic. Subjects completed surveys before the visit, immediately afterwards, at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 5 years. Over 5 years, 25% used CAM for their presenting symptom. Most (72%) reported that CAM helped their symptom. Independent predictors of CAM use included female sex (odds ratio [OR], 2.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-3.7), college educated (OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.8-6.3), more severe symptoms (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01-1.28), and persistence of symptom beyond 3 months (OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 2.0-7.5). We concluded that a quarter of military primary care patients use CAM over 5 years of follow-up and most find it helpful. CAM users tend to be female and better educated. Patients with more severe symptoms or symptoms that persist beyond 3 months are also more likely to turn to CAM.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

INTRODUCTION

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been defi ned as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, therapies, and products that are not currently considered to be part of allopathic medicine. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, a component of the National Institutes of Health, recognizes 4 major domains of CAM: mind–body medicine, body-based/manipulative therapies, biologically based practices, and energy therapy, in addition to whole medical systems that cut across several domains. [1] The use of CAM has been increasing among the general population. In a population-based survey, Eisenberg [2] found that 34% of respondents used some form of CAM in 1991 increasing to 42.1% by 1997. [3] Another general population survey in 2002 found that 62% of respondents used some form of CAM. [4]

Most studies of CAM took 2 forms. They either ask questions about CAM use in general over a specified period of time or study CAM use for specific symptoms, such as tension [5] and migraine headaches, [6] inflammatory bowel disease, [7] arthritis, [5] back pain, [9] HIV, [10] and cancer. [11] Few studies focus on internal medicine patients but none on military medicine beneficiaries. A 2004 ambulatory internal medicine study found that 48.2% of patients had used vitamins, herbal remedies, or folk remedies in the past year [12] for any reason. The purpose of our study was to evaluate the prevalence of CAM for a specific presenting symptom in patients in a general internal medicine clinic, assess the patient’s perspective on the efficacy of CAM for their symptom, and determine clinical predictors of CAM use in this cohort.

METHODS

Patient Selection

Consecutive adults (18 years or older) presenting to the primary care walk-in clinic at Walter Reed Army Medical Center with a chief complaint of a physical symptom were eligible to participate. Of 528 patients approached, 500 agreed to participate. Informed consent was obtained from all participating patients and our Institution’s Review Board approved this study.

Pre-visit Assessment

Immediately before their clinic visit, subjects completed surveys that verified about their symptom characteristics (type, duration, and severity), whether they were worried the problem could be serious, whether they have been under stress in the past week, and a 6-item functional status assessment from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (MOS SF-6). [13] Patients were also screened for mental disorders using the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) screening questionnaire for depressive symptoms. [14] Somatization was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), which asks how much the patient has been bothered during the past month by 15 common physical symptoms. [15] Clinicians completed surveys assessing how difficult the patient was to work with during the index visit using the Difficult Doctor Patient Relationship Questionnaire. [16]

Post-visit Assessment

Immediately after the visit, satisfaction with the clinician in 5 domains (overall, technical competence, bedside manner, time spent with the patient, and explanation of what was done) was assessed with the clinician focused questions in the Medical Outcomes Short Form instrument. [17] Patients were also asked whether they were still worried that the symptoms could be due to a serious medical problem and whether they had post-visit unmet expectations from a check list (diagnosis, prognostic information, prescription, diagnostic test, referral, or other). Patients completed a mailed follow-up questionnaire 2 weeks, 3 months, and 5 years after the visit that assessed symptom outcome, whether they had experienced stress in the past week, whether they were worried the symptoms could represent a serious illness, functional status (MOS SF6), satisfaction, and unmet expectations (explanation of symptom cause or prognosis, prescription, diagnostic test, referral, or other). At 5 years, patients additionally completed the PHQ, as well as symptom-related outcomes, including symptom frequency, how disabling the symptom was, and whether they had received an explanation for their symptoms.

To minimize recall bias, our follow-up questionnaires specified the date of the index appointment, the name of the clinician they saw, and the chief complaint for which they presented using the same words the patient wrote on the initial survey. Finally, subjects were asked at 5 years whether they had used any complementary or alternative therapies for the specific complaint for which they had originally presented. If so, patients were asked to specify any used from a list including chiropractic care, herbal remedies, copper, vinegar, dietary supplements, electricity, salves, special diets, minerals, homeopathy, acupuncture, spiritual healing/prayer, or other. If the patients mentioned others, they were asked to specify what specific therapy was used. If patients reported using CAM, they were asked to rate the effectiveness of CAM on a 5-point Likert scale (helped a lot, helped a little, neither helped nor harmed, made symptom a little worse, or made symptom a lot worse).

Analysis

The primary analysis was the use of CAM, and univariate relationships were explored using the Student t test or the Kruskall–Wallis signed rank test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables (STATA; version 9.0, College Station, Texas). Logistic regression models of predictors of CAM use were built with initial variable selection on the basis of earlier literature and univariate screening, and candidate variables were selected based on p values less than 0.25. Regression model diagnostics, including goodness of fit, assessment for confounding, colinearity, and linearity, were based on the methods of Homser and Lemeshow. [18]

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 Among 500 participating patients, the average age at the index visit was 54.5 years. Fifty-two percent of the patients was female (Table 1), with similar proportions white and African American patients (48% white and 45% African American). One-third reported some college education. Mental disorders were common, with 26% meeting criteria for major depression (8%), anxiety (3%), or multi-somatoform disorder (7.8%) at the time of index visit. Seventy-three participants (14.6%) were active duty military subjects.

Patient chief complaints were collapsed into 14 categories, with musculoskeletal symptoms reported most commonly (Table I). Twenty-one percent had experienced their presenting symptom less than 3 days, 55% less than 2 weeks, and 68% less than a month. Sixty-four percent were worried that their symptom could represent a serious illness. We attained 92% follow-up at 2 weeks, 81% follow-up at 3 months, and 73% follow-up at 5 years. During the 5 years of follow-up, there were 42 deaths (8.4%). By 2 weeks, 18% reported that their symptom had resolved, increasing to 35% at 3 months and 46% at 5 years. Active duty subjects were more likely to experience resolution of their symptom at each time point.

CAM Use

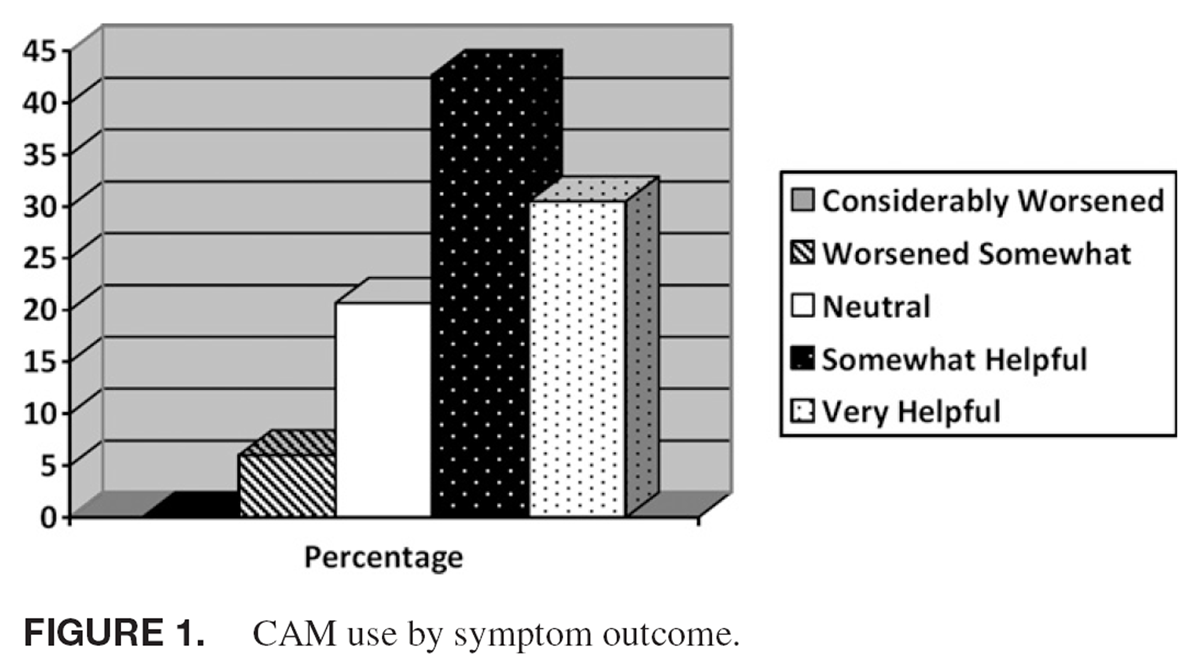

Figure 1 At 5 years, 26% (83/326) of patients reported using CAM for their presenting symptom. No specific symptom was more likely to be treated with CAM than others.

The most commonly utilized CAM was

dietary supplements (27%), followed by

chiropractic care (21%),

minerals (21%), and

spiritual healing (16%).There were a number of correlates with CAM use (Table I), including being female, having at least some college education, having a greater number of “other bothersome” symptoms. In addition, patients who ranked their symptom as more severe at the time of index visit, 2-week and 5-year follow-up were more likely to use CAM. Patients who failed to experience symptom resolution at 2 weeks, 3 months, or 5 years were more likely to try CAM for their specific symptom (Figure 1).

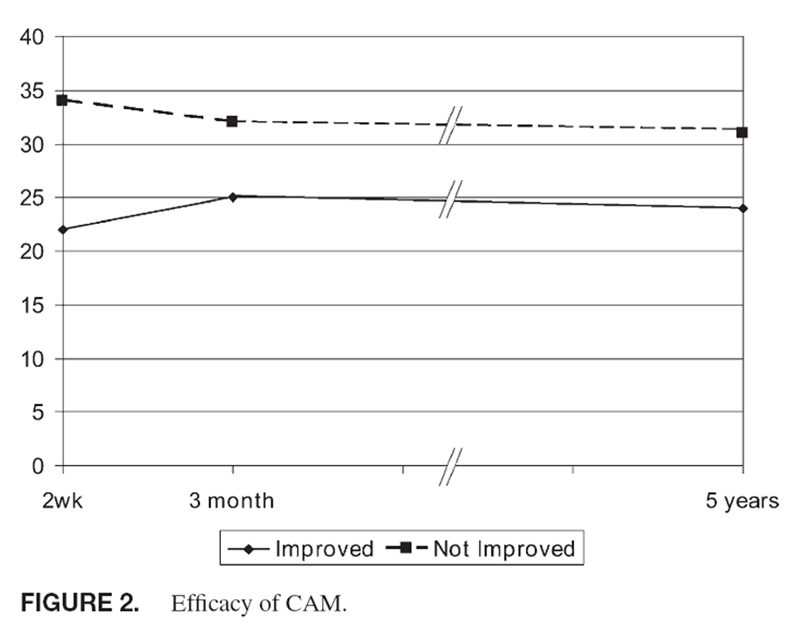

Figure 2 Patients with worse functioning and lower satisfaction were more likely to use CAM as were those with longer symptom duration at the index visit. Patients turning to CAM were more likely to have been rated as “difficult” by their clinician at the index visit. Active duty subjects were less likely to use CAM (27% vs. 22%, p = 0.03). On multi-variable modeling, independent predictors of CAM use included being female (odds ratio [OR], 2.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1–3.7), college educated (OR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.8–6.3), more severe symptoms (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01–1.28), and symptom persistence or recurrence beyond 3 months (OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 2.0–7.5). When adjusted for higher rates of symptom resolution, there was no difference in the use of CAM for active duty vs. nonactive duty subjects.

Among CAM users, 78% felt it was somewhat or very helpful for their physical symptom (Figure 2). Twenty-one percent felt that CAM neither harmed nor helped and 6% felt that CAM made their problem somewhat worse. No one reported that CAM made their symptom “much worse.”

DISCUSSION

In our study, one-quarter of the patients presenting to general medicine clinic used some form of CAM for their specific presenting physical symptom. This is lower than other studies that asked questions about CAM use in general, rather than for a specific symptom. [3–5, 9–11] This is also lower than that found in a general use questionnaire administered to active duty Navy and Marine personnel [19] but similar to rates found in the military millennium cohort. [20] Our findings are consistent with the San Diego Unified Research in Family Medicine Network (SURF*NET) study that found that 21% of family practice patients had used CAM in the past year for their primary health problem leading to their clinic visit, [21]

Our cohort is also consistent with previous studies that have found a higher prevalence of CAM use among women and those with better education. Although CAM use was associated with a number of variables, including longer symptom duration and severity, greater numbers of symptoms, lower functional status, and lower satisfaction, on multivariable analysis, independent predictors of CAM use included female sex, college education, more severe symptoms, and persistence of the symptom beyond 3 months.

Our data have a number of important limitations. First, although we had a good representation from whites and African Americans, there were very few Hispanics or Asians in our study population. These populations need further evaluation in regard to their CAM use because previous studies have shown that use of CAM is related to cultural and health beliefs. [22, 23] In addition, our findings could be susceptible to recall bias because we asked about CAM at 5 years and not at the earlier intervals.

Also, our measure of effectiveness of CAM for the specific symptom was a general question about the patient’s perception of CAM effectiveness. Controlled clinical trails of CAM effectiveness are still lacking for most modalities and symptoms and need to be conducted. Fourth, we did not narrow our symptoms to a specific spectrum, resulting in few patients with some symptom categories. Although this more clearly mirrors the patient population seen in primary care, it limits our results. Finally, there were too few subjects with any specific CAM modality to analyze whether satisfaction or use of CAM varied by specific type of CAM used or the type of symptom for which CAM was used.

There are several strengths of our study. First, the large size of the cohort and high follow-up rates at 5 years allow for strong statistical correlations. Second, this study adds to our understanding of CAM use in ambulatory medicine. Our findings suggest that large proportions of general internal medicine patients are using CAM for their presenting symptom, emphasizing the need for internists to ask about CAM use with every visit. Clinicians often do not ask about CAM and patients frequently are not forthcoming, with nondisclosure rates up to 72%. Patients often report lack of reporting simply because their clinicians did not ask, amongst other reasons like not feeling it was important for their doctor to know. [24] In addition, our data show that certain subgroups have higher rates of CAM use. Patients with more severe symptoms and those with symptom persistence beyond 3 months should particularly be questioned about CAM use by their clinicians.

References:

Alternative Medicine: Expanding Medical Horizons.

National Institute of Health.

Washington, DC , U.S. Government Printing Offi ce , 1992Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Morlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL.

Unconventional Medicine in the United States: Prevalence, Costs, and Patterns of Use

New England Journal of Medicine 1993 (Jan 28); 328 (4): 246–252Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC.

Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990 to 1997:

Results of a Follow-up National Survey

JAMA 1998 (Nov 11); 280 (18): 1569–1575Barnes PM , Powell-Grinner E , McFann K , Nahin RL:

Complimentary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002.

Adv Data 2004 ; 343: 1–19.Rossi P , Di Lorenzo G , Faroni J , Malpezzi MG , Cesarino F , Nappi G:

Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with chronic tension-type headache:

results of a headache clinic survey.

Headache 2006 ; 46 (4): 622–31.Rossi P , Di Lorenzo G , Malpezzi MG , et al:

Prevalence, pattern and predictors of use of complementary and alternative medicine(CAM) in migraine

patients attending headache clinic in Italy.

Cephalgia 2005 ; 25 (7): 493–506.Burgmann T , Rawsthorne P , Bernstein CN:

Predictors of alternative and complementary medicine use in inflammatory bowel disease:

do measures of conventional health care utilization relate to use?

Am J Gastroenterol 2004 ; 99 (5): 889–93.Herman CJ , Allen P , Hunt WC , Prasad A , Brady TJ:

Use of complementary therapies among primary care clinic patients with arthritis.

Prev Chronic Dis 2004 ; 1 (4): A12.Lind BK , Lafferty WE , Tyree PT , Sherman KJ , Deyo RA , Cherkin DC:

The role of alternative medical providers for the outpatient treatment of insured patients with back pain.

Spine 2005 ; 30 (12): 1454–9.Fairfield KM , Eisenberg DM , Davis RB , Libman H , Phillips RS:

Patterns of Use, Expenditures, and Perceived Efficacy of Complementary and Alternative

Therapies in HIV-Infected Patients

Archives of Internal Medicine 1998 (Nov 9); 158 (20): 2257–2264Shumay DM , Maskarinec G , Gotay CC , Heiby EM , Kakai H:

Determinants of the degree of complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with cancer.

J Altern Complement Med 2002; 8 (5): 661– 71.Rhee SM , Vinod KG , Hershey CO:

Use of complementary and alternative medicines in ambulatory patients.

Arch Intern Med 2004 ; 164: 1004–9.Ware JE , Nelson EC , Sherbourne CD , Stewart AL:

Preliminary tests of a 6-item general health survey: a patient application.

In: Measuring Functioning and Well Being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach , pp 199–308.

Edited by Stewart AL , Ware JE.

Durham, Duke University Press , 1997.Spitzer RL , Kroenke K , Williams JB:

Validation and utility of a self report version of the PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study.

Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire.

JAMA 1999 ; 282 (18): 1737–44.Kroenke K , Spitzer RL , Williams JB:

The PHQ 15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms.

Psychosom Med 2002 ; 64 (2): 258–66.Jackson JL , Kroenke K:

Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes.

Arch Intern Med 1999 ; 159 (10): 1069–75.Rubin HR , Gandek B , Rogers WH , Kosinski M , McHorney CA , Ware JE Jr:

Patients’ ratings of outpatient visits in different practice settings. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study.

JAMA 1993 ; 270: 1449–53.Hosmer DW , Lemeshow S:

Applied logistic regression. Ed 2.

Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics.

New York, NY , John Wiley and Sons , 2000.Smith TC, Ryan MA, Smith B, et al.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among US Navy and Marine Corps Personnel

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007 (May 16); 7: 16Jacobson IG , White MR , Smith TC , et al:

Self-reported health symptoms and conditions among complementary and alternative medicine users

in a large military cohort.

Ann Epidemiol 2009 ; 19 (9): 613–22.Palinkas LA , Kabongo ML:

The use of complementary and alternative medicine by primary care patients. A SURF*NET study.

J Fam Pract 2000 ; 49: 1121–30.Lee GB , Charn TC , Chew ZH , Ng TP:

Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients with chronic diseases in primary care is associated

with perceived quality of care and cultural beliefs.

Fam Pract 2004 ; 21: 654–60.Hsiao AF , et al:

Variation in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use across racial/ethnic groups and the

development of ethnic specific measures of CAM use.

J Altern Complement Med 2006 ; 12 (3): 281–90.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Van Rompay MI, Kaptchuk TJ, Wilkey SA, Appel S.

Perceptions About Complementary Therapies Relative To

Conventional Therapies Among Adults Who Use Both:

Results From A National Survey

Annals of Internal Medicine 2001 (Sep 4); 135 (5): 344–351

Return to ALT-MED/CAM ABSTRACTS

Return to CHIROPRACTIC CARE FOR VETERANS

Since 3-21-2020

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |