Ethical Considerations of Ccmplementary and Alternative

Medical Therapies in Conventional Medical SettingsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (Oct 15); 137 (8): 660–664 ~ FULL TEXT

David M. Eisenberg, MD; Roger B. Davis, ScD; Susan L. Ettner, PhD;

Scott Appel, MS; Sonja Wilkey; Maria Van Rompay; Ronald C. Kessler, PhD

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology UHNSO,

Oregon Health and Science University,

3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road,

Portland, OR 97239, USA.

adamsk@ohsu.eduIncreasing use of complementary and alternative medical (CAM) therapies by patients, health care providers, and institutions has made it imperative that physicians consider their ethical obligations when recommending, tolerating, or proscribing these therapies. The authors present a risk-benefit framework that can be applied to determine the appropriateness of using CAM therapies in various clinical scenarios. The major relevant issues are the severity and acuteness of illness; the curability of the illness by conventional forms of treatment; the degree of invasiveness, associated toxicities, and side effects of the conventional treatment; the availability and quality of evidence of utility and safety of the desired CAM treatment; the level of understanding of risks and benefits of the CAM treatment combined with the patient's knowing and voluntary acceptance of those risks; and the patient's persistence of intention to use CAM therapies. Even in the absence of scientific evidence for CAM therapies, by considering these relevant issues, providers can formulate a plan that is clinically sound, ethically appropriate, and targeted to the unique circumstances of individual patients. Physicians are encouraged to remain engaged in problem-solving with their patients and to attempt to elucidate and clarify the patient's core values and beliefs when counseling about CAM therapies.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Because the use of complementary and alternative medical (CAM) therapies is becoming increasingly widespread in the United States [1, 2], physicians with traditional training now confront a complex array of ethical dilemmas. The conventional physician in the United States is relatively unfamiliar with CAM therapies, a lack of consensus exists among orthodox health care providers about CAM use within conventional medicine, and scientific evidence for CAM therapies is rapidly shifting. Such an environment creates a potential for serious physician–patient conflict, as well as patient harm, when CAM and conventional medical therapies intersect. [3–5] Some CAM therapies in and of themselves can be hazardous, but harm can also occur indirectly when patients choose less effective CAM treatments instead of conventional methods that have demonstrated efficacy. In individual situations in which evidence supporting CAM therapies is good, more subtle forms of harm can manifest when a provider, either through bias against such therapies or lack of knowledge, presents conventional treatment as the only available option. In such situations, a patient could be deprived of potentially useful CAM treatments, may be unable to actively participate in decision making, and may be left without medical supervision and monitoring while using CAM therapies.

Physician–patient conflict may also occur when the patient considers the use of CAM treatments that are not supported by evidence-based medicine. Although some CAM therapies have been subjected to randomized, controlled trials, evidence for many types of CAM therapies is quite thin or simply does not exist. Some of these therapies also have a strong spiritual component that relates directly to a person’s belief system, and some patients choose such treatments despite a lack of evidence of benefit—or worse, despite clear evidence that such treatments are ineffective. The challenge for physicians in such situations is to provide ethical, medically responsible counseling that respects and acknowledges the patient’s values. Physicians should not violate their own values in the process of responding to a patient’s needs or abandon the practice of evidence-based medicine in order to provide support for their patients’ beliefs. A long-standing, carefully nurtured partnership between physician and patient that has grown over time may be strained or completely destroyed if common ground in such situations cannot be found. Choosing to withdraw from care of a patient because of a fundamental conflict is a decision that requires intense self-examination by the physician and consultation with trusted colleagues; it is a decision that is never made lightly. [6] Physician–patient conflict arising from issues related to use of CAM therapies is common, but the need to withdraw from care should be rare if physicians are willing to engage creatively with patients when problems seem unsolvable. [7, 8] However, even physicians who are willing to consider CAM treatments in some circumstances find it difficult to know how to responsibly and ethically advise patients in this unfamiliar realm of medicine. They feel uninformed about CAM therapies and ill-equipped to judge the quality of CAM providers.

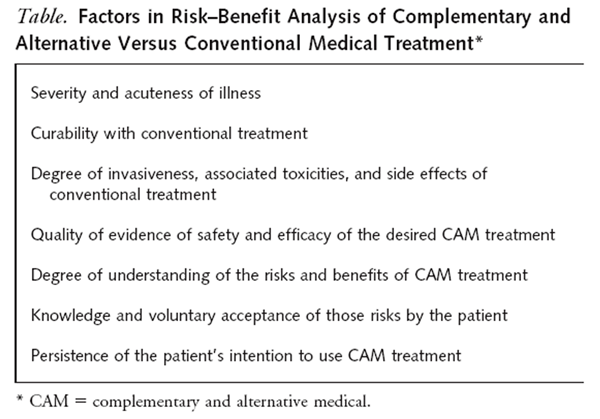

We present two prototypical cases that illustrate the challenges already discussed as well as other ethical challenges that will arise as use of CAM therapies in the United States becomes even more common. The use of case-based reasoning, or casuistry, in questions of CAM therapy use allows a fuller appreciation of the way in which circumstances play an intrinsic role in moral judgments. [9, 10] Specific details of each case are particularly relevant in guiding ethical decision making (Table). This information forms a risk– benefit framework in which varying degrees of illness, efficacy, safety, and patient choice help guide a conventional physician to recommend, tolerate, or proscribe the use of CAM therapies. Application of this familiar type of risk– benefit analysis to questions of CAM use can help providers develop a treatment plan that responsibly fulfills their ethical obligations while recognizing and allowing consideration of the unique circumstances of each case.

CASE 1

Ms. P., a 52–year-old woman, sees a naturopath for her primary care. The naturopath refers Ms. P. to a gynecologist for evaluation of an abnormal Papanicolaou smear performed at an annual examination in the naturopath’s office. Cervical biopsies reveal adenocarcinoma in situ, a premalignant condition that, if left untreated, can progress to invasive adenocarcinoma. The gynecologist recommends a cervical conization or hysterectomy to ensure that all abnormal tissue is identified and removed. Ms. P. is a Reiki practitioner, trained to perform a type of energy healing that is said to involve moving energy through the body in order to balance it. She tells the physician that she plans to pursue meditation, colonics, and yoga and to work with her Reiki master rather than have surgery. She further states that she does not want any “surgical invasion of her bodily integrity.” The gynecologist feels unable to change Ms. P.’s mind, is concerned about her prognosis, and is unsure about remaining in the physician–patient relationship.

Analysis of this case begins with consideration of the factors presented in the Table. Ms. P. has a precancerous condition that, if left untreated, has a high likelihood of progressing to invasive cancer within several years. The conventional treatment offered is admittedly invasive but at this point should be completely curative. Ms. P. is highly motivated to seek CAM therapies, but although there are some data on the beneficial effect of her chosen treatments for some conditions [11, 12], no data support successful treatment of a precancerous condition. In addition, these treatments are generally used to increase overall well-being rather than to cure a specific physiologic abnormality.

Ms. P. is legally competent; the law presumes persons are competent unless a judge has ruled them incompetent. However, a physician faced with a seeming inexplicable decision by a patient must explore the patient’s capacity for decision making. Capacity requires at least an ability to understand relevant information, to appreciate one’s medical choices and their possible consequences, to communicate a choice, and to engage in rational deliberation about one’s own values in relation to the physician’s recommendations about treatment options. [13] Review of Ms. P.’s records showed that she had no psychiatric history, but that she had been sexually abused as a child and, as an adult, had received counseling regarding this history. She had been practicing for the previous 4 years as a Reiki therapist, trained to move energy throughout the body in a way that is said to provide balance and healing. Ms. P. exhibited no verbal or behavioral signs of mental illness.

Once the physician was satisfied that the patient’s decision-making capacity was adequate, the physician had to ensure that Ms. P. was fully informed by carefully explaining the potential risks involved and attempting to persuade her to change her mind. The physician approached the patient by saying, “As far as I am able to tell, you don’t have cancer now, but the condition you have often does progress to cancer, and the more time that passes before you have these cells removed, the more likely it is that they eventually will turn into cancer. I’m concerned that if you delay treatment by trying some of these other methods, none of which have been shown to be effective in treating your condition, you may end up with cancer, which will be much more difficult, if not impossible, to cure.” The patient should show understanding of the risks, a willingness and ability to communicate about them, and a capacity to rationally deliberate.

Ms. P. listened carefully to everything the physician said, and, as the physician listened equally intently, it became clear to him that Ms. P.’s choice reflected her values of noninvasion of the body; belief in the body’s ability to heal itself; and the importance of the relationship between illness and mental, emotional, and spiritual health. Although she had had chaotic and difficult early years, Ms. P. had found solace and peacefulness in her beliefs, which influenced every part of her life. She not only practiced Reiki herself but taught the techniques to others and had even established a newsletter that was circulated among other Reiki practitioners and their clients. At one point, Ms. P. stated firmly and calmly, “Even if you told me I would die next month without surgery, I still wouldn’t have it.” The physician began to feel that not only would any further attempt to convince Ms. P. to undergo surgery be disrespectful of these deeply held core values, but that her internal sense of integrity could be irretrievably harmed were she to undergo a procedure that was not congruent with her beliefs.

As a general principle, the personal beliefs and choices of other persons should be respected if they pose no threat to other parties. [13] The dilemma for the physician in this case became whether to continue providing care for Ms. P. when it was clear that her values were deeply held and durable: There was really no expectation that she would change her mind and agree to the physician’s recommendation. The resolution in this case was relatively straightforward. Because Ms. P. had seen the gynecologist only in consultation, she was free to reject the recommendation for surgery and return to her naturopath for continued medical care, with an invitation to return to the physician if she desired further discussion. Informed refusal of care was carefully documented, and the physician contacted the naturopath, who felt able to continue to provide care for Ms. P. despite her refusal of surgery.

The question of withdrawal from care becomes more difficult when the physician in question is the patient’s primary care provider; in this situation, the ongoing relationship with the patient must be considered. The ethical obligation of nonabandonment emphasizes the longitudinal nature of a caring commitment between physician and patient. The promise to face the future together is a central obligation of the physician–patient relationship, which carries with it a commitment by the physician to jointly seek solutions with patients throughout their illnesses. [6, 14, 15]The limits of this obligation will vary, depending on such things as the length of time of the relationship, the patient’s other medical conditions, and the patient’s desire for continued care from this physician. Ms. P.’s refusal of surgery may be seen by some physicians as an understandable— albeit incorrect—decision, given the totality of her circumstances. These physicians would feel able to continue as her primary care provider. In the case of Ms. P., the physician should explain his viewpoint—that he considers her decision a serious mistake but is willing to continue providing long-term care for her, even if she develops cancer. Others may find her decision unsupportable, feeling that continuing to provide care would involve giving tacit approval to an irresponsible decision. Such physicians would opt to withdraw from her care and make a referral to a more like-minded physician. But the obligation of nonabandonment challenges us to meet and engage with our patients in conflicts, not shy away from them by recourse to unbending rules or blindly following some imaginary, clearcut boundary about what is acceptable or unacceptable. [6] Patients do not always expect medical solutions to their problems, and withdrawal of care should happen only when the physician’s own values compel such a decision. Physicians who feel that remaining in the relationship provides false reassurance to the patient should review the patient’s decision-making process (and remind themselves that the patient came to this choice with full awareness of the possible consequences) and should avoid overemphasizing their own role as the patient carries out his or her decision.

CASE 2

Ms. L., a 48–year-old woman with recurrent metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma, seeks an oncologist who will provide her with conventional treatment but is open to the use of CAM treatments as adjunctive therapy. She wants her provider to assist her in evaluating available CAM treatments and give guidance about their appropriateness for her. She raises the issue with her oncologist, who dismisses the subject, explaining that she cannot recommend CAM treatments because they have not been subjected to scientific scrutiny and that the patient is risking her health in seeking these types of care. The physician further comments that if there were any evidence that CAM therapies could help, she would offer them herself. Ms. L. cannot switch providers because her insurance plan requires she be seen by this oncologist, and she feels frustrated in her attempts to engage with her physician in this aspect of her care.

Ms. L. has requested information regarding the effectiveness of CAM treatments as an adjunct to, not as a substitute for, the planned conventional treatment of her metastatic cancer. Her oncologist states that there is no evidence that any CAM therapies are useful in this regard. Actually, however, data support the use of various types of CAM treatments for patients with cancer. For example, the positive effects of relaxation training for improving anxiety and decreasing pain [16]; of acupuncture for diminishing nausea associated with chemotherapy [17]; and of psychotherapy, group therapy, relaxation, and imagery for improving the quality of life in patients with breast cancer [18] have all been suggested through controlled trials. In contrast, many herbal and metabolic regimens that have been proposed for the primary treatment of cancer are currently not supported by scientific evidence. [19] The other relevant factors in this case are that Ms. L.’s condition is chronic and severe, with a low expectation of cure with traditional methods, and that she is highly motivated to use CAM therapies, which may improve her quality of life. In undertaking CAM treatments, she may also regain some sense of control over her physical, psychological, and spiritual health. Also of importance is that she is actively seeking the guidance and advice of her conventional caregiver.

In such a situation, the patient’s choice of CAM therapies should be respected. The increasing body of research regarding the effectiveness of some types of CAM therapies [19–21] helps clinicians to judge the advisability of these therapies according to the following criteria. As suggested by other authors, in making such judgments, consideration should be given to whether available evidence 1) supports both safety and efficacy; 2) supports safety but is inconclusive about efficacy; 3) supports efficacy but is inconclusive about safety; or 4) indicates either serious risk or inefficacy. [22]

If evidence supports both safety and efficacy, the physician should recommend the therapy but continue to monitor the patient conventionally. If evidence supports safety but is inconclusive about efficacy, the treatment should be cautiously tolerated and monitored for effectiveness. If evidence supports efficacy but is inconclusive about safety, the therapy still could be tolerated and monitored closely for safety. Finally, therapies for which evidence indicates either serious risk or inefficacy obviously should be avoided and patients actively discouraged from pursuing such a course of treatment. This risk framework for CAM therapies allows the physician to make a thoughtful decision that will be evidence based, ethically appropriate, and legally reasonable. [22] In the case of Ms. L., the oncologist could therefore reasonably respond to the patient’s request for guidance about CAM therapies by considering acupuncture for the patient’s chemotherapy-associated nausea and mind–body techniques, such as relaxation and imagery, for anxiety and pain.

It is not difficult for a physician to counsel a patient about CAM therapies for which evidence exists. No one would disagree that physicians should be aware of pertinent evidence and be willing to consider any intervention, CAM or allopathic, that has an acceptable risk–benefit balance; apprise the patient of acceptable options; and make a recommendation. In fact, the obligation of informed consent requires that physicians raise and discuss CAM therapy options that have been shown to be efficacious. [23] An example of one such option is lifestyle programs that include yoga, meditation, exercise, and dietary changes for the treatment of heart disease. [11] Likewise, a physician should take the initiative to proactively steer patients away from treatments that are known to be dangerous or have been associated with clinically significant adverse interactions with other supplements or medications. [23–26] CAM therapies have become so common that inquiries about their use should become a routine part of history taking. [27]

There are currently many situations for which no reliable evidence about CAM therapies exists but patients nonetheless request these treatments; in such cases, physicians must counsel and advise in the absence of evidence. When there is no evidence either for or against a particular therapy, physicians can choose to tolerate and monitor or actively discourage use of CAM treatments. The risk–benefit framework presented in the Table is helpful in counseling because the unknown CAM therapy can be compared with what is known about the competing conventional treatment and the relative risk of choosing the CAM therapy can be assessed. If, for example, the conventional treatment is effective and the risk for not treating is great, a patient would be ill-advised to pursue an unproven CAM therapy, and the physician should actively discourage such a decision. If, however, the standard conventional therapy is ineffective, even an unproven CAM therapy could be tolerated, because the patient has few, if any, good alternatives. An unproven therapy may have unknown toxicities, and patients should be clearly informed about the lack of information on the safety of untested CAM therapies, particularly if the condition being treated is minor.

Such discussions between physician and patient are the heart of informed consent, and a physician’s recommendations are often the beginning rather than the ending of an exchange that will ultimately determine the course the patient chooses. It can be helpful to begin the discussion by focusing on general goals of treatment (for example, care vs. cure) rather than moving immediately to a consideration of specific interventions, which may lead the patient to prematurely choose therapy that may not serve his or her ultimate goals well. [28] The final choice of treatment belongs to the patient and should reflect his or her beliefs and values; physicians should seriously consider and try to respond to the patient’s needs to the fullest possible extent without violating their own values. For example, if Ms. L. refused chemotherapy in favor of some unproven herbal preparation, the approach should be similar to that of the physician caring for Ms. P. She and her physician should first attempt to reach a common understanding of the nature of her condition, her prognosis, and the goals of treatment. If she persisted in rejecting chemotherapy, her physician would have an appreciation of the reasons supporting this choice and would hopefully feel able to provide Ms. L. with a continued open-ended commitment to long-term joint problem-solving despite her refusal of conventional care. [6]

Physicians routinely refer patients to other practitioners and can be expected to be able to judge the skill of their physician colleagues; however, physicians with no training in a particular complementary therapy, such as acupuncture, will find it difficult to be a reasonable judge of CAM providers. Therefore, it is of paramount importance that physicians have some understanding of currently existing methods of credentialing various types of CAM providers [29] as well as the potential liability associated with these referral relationships. [22, 30] The reader is referred to the considerations of credentialing CAM providers and malpractice liability associated with CAM discussed elsewhere in this series. [22, 29]

CONCLUSION

Increasing use of CAM therapies in the United States provides an opportunity to reexamine the ethical foundations of western medical practice with renewed attention to the commitment physicians make when entering into a caring relationship with a patient. Physicians routinely balance risks and benefits in decision making, but the advent of CAM therapies challenges physicians to deal responsibly with paradigms of healing that fall outside the boundaries of conventional medical practice and to make decisions in these unfamiliar realms, often in the absence of evidence. Specific details of each case should be factored into a risk– benefit assessment so that a plan of treatment that is clinically reasonable and ethically appropriate can be developed.

The commitment to joint problem solving over time that is a central obligation of the physician–patient relationship becomes even more important when considering the use of CAM therapies. Elucidating patients’ experiences of illness, their hopes and values, and what they see as their best interests is vital if physicians and patients are to find common ground when making decisions in areas of uncertainty. As the body of evidence regarding CAM therapies grows, we hope that the model of decision making we have presented will provide an ethical structure for medical practice in which physicians routinely combine the powerful tools of conventional medicine with those CAM therapies shown to be worthy of clinical integration.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the two patients who allowed us to share their stories, Debbie Mosley for invaluable technical assistance, and Martin Donohoe for critical comments.

Grant Support:

By unrestricted educational grants from the American Specialty Health Plans, San Diego, California; the Medtronic Foundation, Minneapolis, Minnesota; and the Friends of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts.

References:

Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, Kessler RC.

Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990 to 1997:

Results of a Follow-up National Survey

JAMA 1998 (Nov 11); 280 (18): 1569–1575Eisenberg DM.

The Invisible Mainstream.

Harvard Medical Alumni Bulletin. 1996;70:20-5.Angell M, Kassirer JP.

Alternative Medicine: The Risks of Untested and Unregulated Remedies: A Medical Opinion

New England Journal of Medicine 1998 (Sep 17); 339 (12): 839-841Kottow MH.

Classical medicine v alternative medical practices.

J Med Ethics. 1992;18:18-22. [PMID: 1573644]Kramer N.

Why I would not recommend complementary or alternative therapies: a physician’s perspective.

Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999;25:833-43, vii. [PMID: 10573760]Quill TE, Cassel CK.

Nonabandonment: a central obligation for physicians.

Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:368-74. [PMID: 7847649]Quill TE.

Partnerships in patient care: a contractual approach.

Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:228-34. [PMID: 6824257]Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL.

Four models of the physician-patient relationship.

JAMA. 1992;267:2221-6. [PMID: 1556799]Jonsen AR.

Casuistry and clinical ethics.

In: Jecker NS, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA, eds.

Bioethics: An Introduction to the History, Methods and Practice.

New York: Jones and Bartlett; 1997:158-61.Jonsen AR.

Casuistry: an alternative or complement to principles?

Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1995;5:237-51. [PMID: 11645308]Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Doody RS, Kesten D, McLanahan SM, Brown SE, et al.

Effects of stress management training and dietary changes in treating ischemic heart disease.

JAMA. 1983;249:54-9. [PMID: 6336794]Long L, Huntley A, Ernst E.

Which complementary and alternative therapies benefit which conditions? A survey of the opinions of 223 professional organizations.

Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:178-85. [PMID: 11926432].Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ.

Clinical Ethics. 3rd ed.

New York: McGraw-Hill; 1992.May WE.

The Physician’s Covenant: Images of the Healer in Medical Ethics.

Philadelphia: Westminster Pr; 1983.Ramsey P.

The Patient as Person: Explorations in Medical Ethics.

New Haven: Yale Univ Pr; 1970.Integration of Behavioral and Relaxation Approaches into the Treatment of Chronic Pain and Insomnia.

NIH Technology Assessment Statement, NIH Publication No. PB96113964.

Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1995: 1-34.NIH Consensus Conference.

Acupuncture.

JAMA. 1998;280:1518-24. [PMID: 9809733]Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Kraemer HC, Gottheil E.

Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer.

Lancet. 1989;2: 888-91. [PMID: 2571815]Fugh-Berman A.

Alternative Medicine: What Works.

Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997.Jonas W, Levin J, eds.

Essentials of Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999.Spencer J, Jacobs J, eds.

Complementary/Alternative Medicine: An Evidence-Based Approach.

New York: Mosby; 1999.Cohen MH, Eisenberg DM.

Potential physician malpractice liability associated with complementary and integrative medical therapies.

Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:596-603. [PMID: 11955028]Cohen MH.

Beyond Complementary Medicine: Legal and Ethical Perspectives on Health Care and Human Evolution.

Ann Arbor, MI: Univ of Michigan Pr; 2000.Ernst E.

Second thoughts about safety of St John’s wort.

Lancet. 1999;354: 2014-6. [PMID: 10636361]Fugh-Berman A.

Herb-drug interactions.

Lancet. 2000;355:134-8. [PMID: 10675182]Piscitelli SC, Burstein AH, Chaitt D, Alfaro RM, Falloon J.

Indinavir concentrations and St John’s wort [Letter].

Lancet. 2000;355:547-8. [PMID: 10683007]Eisenberg DM.

Advising Patients Who Seek Alternative Medical Therapies

Annals of Internal Medicine 1997 (Jul 1); 127: 61-69Quill TE, Brody H.

Physician recommendations and patient autonomy: finding a balance between physician power and patient choice.

Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:763-9. [PMID: 8929011]Eisenberg DM, Cohen MH, Hrbek A,Grayzel J, Cooper RA.

Credentialing complementary and alternative providers.

Ann Intern Med. [In press].Studdert DM, Eisenberg DM, Miller FH, Curto DA, Kaptchuk TJ, Brennan TA.

Medical malpractice implications of alternative medicine.

JAMA. 1998; 280:1610-5. [PMID: 9820265]

Return to EISENBERG's CAM ARTICLES

Since 11-15-2002

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |