Plasmacytoma of the Cervical Spine:

A Case StudyThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Chiropractic Medicine 2017 (Jun); 16 (2): 170–174 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Richard Pashayan, DC, DABCO, CCSP, Wesley M. Cavanaugh, DC,

Chad D. Warshel, DC, DACBR, and David R. Payne, MD

Private Practice,

Flushing, NY.OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this case study is to describe the presentation of a patient with plasmacytoma.

CLINICAL FEATURES: A 49-year-old man presented with progressive neck pain, stiffness, and dysphagia to a chiropractic office. A radiograph indicated a plasmacytoma at C3 vertebral body. The lesion was expansile and caused a mass effect anteriorly on the esophagus and posteriorly on the spinal cord. Neurologic compromise was noted with fasciculations and hypesthesia in the right forearm. The patient was referred to a neurosurgeon.

INTERVENTION AND OUTCOME: Surgical resection of the tumor was performed with a vertebral body spacer and surrounding titanium cage. Bony fusion was initiated by inserting bone grafts from the iliac crests into the titanium cage. Additional laboratory analysis and advanced imaging confirmed that the plasmacytoma had progressed to multiple myeloma and radiation and chemotherapy were also necessary.

CONCLUSION: A chiropractor recognized a large, expansile plasmacytoma in the C3 vertebral body and referred the patient for surgical care. This case suggests that all practitioners of manual medicine should provide a careful analysis of the patient's clinical presentation and, if clinically warranted, radiographic examination to determine neck or back pain is due to an underlying malignant condition.

KEYWORDS: Bone Neoplasms; Multiple Myeloma; Neoplasms, Plasma Cell; Plasmacytoma

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Multiple myeloma is a malignant disease usually originating in the bone marrow, although other tissues may be involved. The age of onset for the average multiple myeloma patient is 60 to 70 years, [1] although it can manifest in younger patients on rare occasions. It is characterized by an idiopathic and uncontrolled proliferation of plasma cells that replace normal healthy tissue. Laboratory evaluation of blood samples in such patients may reveal a number of characteristic findings, such as an increase in the number of serum plasma cells, reversal of the ratio of albumin to globulin in the blood (albumin normally accounts for greater than 50% of total serum proteins), a spike in immunoglobulin M gammaglobulins, and an excessive number of polypeptide subunits of the immunoglobulin M proteins (specifically, Bence Jones proteins, which can be most easily detected in a urinalysis). In 75% of cases of multiple myeloma, skeletal lesions present with osteolysis in the form of discrete “punched-out” lesions. [2] The axial skeleton is affected more often than the extremities. Multiple lesions are most commonly apparent in the vertebrae, ribs, skull, pelvis, and femur, in descending order of frequency.

This malignancy, while common in regard to tumor incidence, is not frequently reported in the chiropractic literature. The purpose of this case study is to describe the clinical presentation and imaging characteristics of a patient with plasmacytoma who presented to a chiropractic clinic.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man presented to his chiropractor with the complaint of neck stiffness of 4 months’ duration followed by severe progressive radiating neck pain of 2 months’ duration. The patient also experienced fasciculations in his right forearm, which started 3 weeks before presentation. He also complained of progressive dysphagia that started at the same time as his fasciculations. His neck pain was reported on a verbal pain scale as an 8 out of 10. He rated his neck stiffness at an 8 to a 10 out of 10. His neck symptoms worsened while riding the train, with increased mental or emotional stress, with all cervical ranges of motion, and when maintaining his head in one position for extended periods. He stated that nothing relieved his pain. His cervical range of motion became severely limited 2 months before presentation. He experienced dysphagia for approximately 2 months as his neck pain and stiffness worsened. At that time he saw an orthopedist and was prescribed tramadol for pain management. The patient consulted his primary care physician, who prescribed muscle relaxers, diazepam (Valium), escitalopram (Lexapro), anti-inflammatories, and more tramadol. No radiographs were taken by the orthopedist or the primary care physician. The patient’s review of systems and additional medical history were noncontributory.

The doctor of chiropractic performed a clinical examination, which revealed active range of motion that was painful and reduced by approximately 60% in all directions, pain on deep palpation, spasm of the cervical paraspinal muscles, local pain with cervical compression that radiated to the tops of both shoulders, relief of pain with cervical distraction, and a positive Soto Hall test (sharp electrical pain radiating down the spine on cervical flexion). There was a slight decrease in sensation over the right forearm in the C5 dermatome with +2 upper extremity reflexes.

Diagnostic Imaging

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

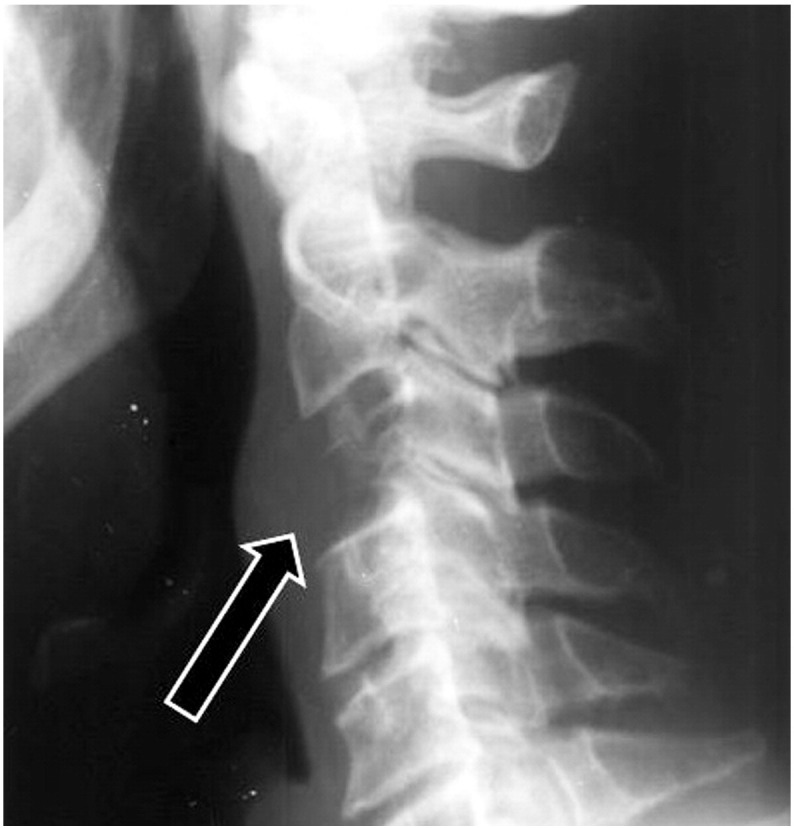

Figure 4 Cervical radiographs taken by the chiropractor (Figure 1, Figure 2) revealed lytic destruction of the C3 vertebral body with possible involvement of the transverse processes of C3. The posterior elements of C3 and the adjacent endplates of C2 and C4 were spared. Anterior displacement of the laryngopharynx was also noted, with prevertebral soft tissues measuring approximately 10 mm, where normal maximum thickness is 7 mm.

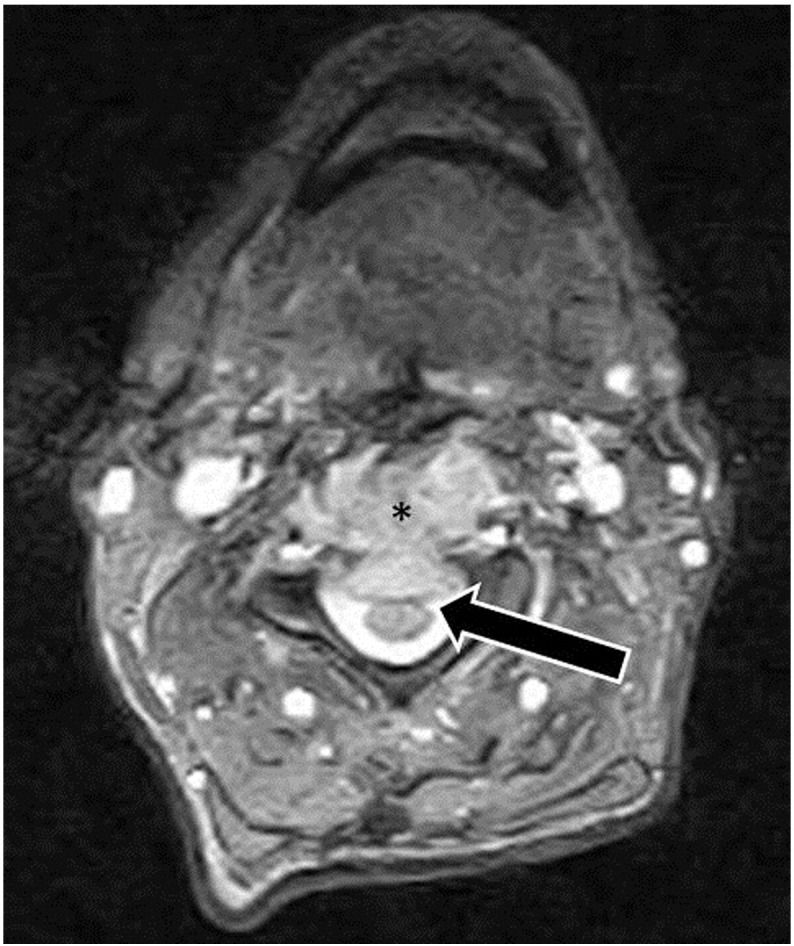

The doctor of chiropractic referred the patient to a local imaging center for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his cervical spine, and the images were interpreted by a neuroradiologist (Fig 3, Fig 4). Circumferential expansion of the C3 vertebral body (more pronounced on the left) was noted with extension into anterior soft tissues from the inferior endplate of C2 through the superior endplate of C4. The anterior longitudinal ligament adjacent to C3 was displaced 8 mm anteriorly with accompanying anterior displacement of the laryngopharynx. There was 5 mm of posterior expansion of the C3 vertebral body causing impingement of the thecal sac and effacement of the spinal cord. Low T1 signal intensity of the bone marrow of the C3 vertebral body with pronounced cortical attenuation, but no cortical destruction was appreciated. The tumor involved the right transverse process of C3 with engulfment of the vertebral artery on that side. The T2 signal of the C3 body was isointense to surrounding bone marrow. Normal T1 and T2 signal intensity of the spinal cord and surrounding cerebrospinal fluid was noted. A solitary plasmacytoma of the C3 vertebral body was considered to be the most likely diagnosis, with chordoma being a likely differential diagnosis. Less likely differential diagnoses included metastasis, vertebral osteomyelitis, and primary lymphoma.

Treatment

A neurosurgical referral was scheduled for the next day, and the patient was admitted to a local hospital. The patient underwent surgical resection of the tumor with placement of a vertebral body spacer and a titanium cage surrounding the C2, C3, and C4 vertebral bodies. Bone grafts harvested from the iliac crests were inserted into the cage to trigger bony fusion of the affected vertebrae.

Subsequent radiographic and scintigraphic imaging revealed that the patient had lytic destruction in multiple locations of his ribcage and in his pelvis. These results, combined with serum electrophoresis and urinalysis, confirmed the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. It is theorized that the solitary plasmacytoma of C3 was the precursor lesion for development of multiple myeloma.

The patient communicated to his doctor of chiropractic that radiation therapy and chemotherapy would commence soon thereafter to eradicate any remaining traces of malignancy. Bone-hardening chemicals and stem cell therapy would also be used after chemotherapy was complete to encourage the surgical fusion to progress as rapidly as possible. The patient provided consent for the publication of this report.

Discussion

A plasmacytoma is considered to be a solitary form of multiple myeloma. [1] These lesions are typically found in the vertebral bodies of the thoracic and lumbar spine in patients with an average onset age of 50 years. This is in contrast to the average onset age for multiple myeloma, which is 60 to 70 years. Men are slightly more likely than women to develop both plasmacytoma and multiple myeloma. [3] Cervical spine involvement is found in only 8% of cases, [4] and pedicle involvement occurs in approximately 20% of cases. [5] The disease can progress fairly rapidly, but when plasmacytoma and multiple myeloma (or both) present in younger patients, they typically follow a more indolent course. [6] The median overall survival rate for solitary plasmacytoma of bone varies from 7.5 to 12 years, [7] and vertebral involvement has been reported as a poor prognostic factor compared with other sites of skeletal involvement. [8]

The serum and urinalysis laboratory findings that characterize multiple myeloma are almost never present in a patient with a solitary plasmacytoma. Dissemination from a solitary plasmacytoma to multiple myeloma occurs within 5 years of initial presentation up to 80% of the time. Rarely, it may occur after 20 years or more. In some patients, the solitary lesion may never disseminate. This has led to some debate about the very existence of a solitary plasmacytoma; some researchers consider a nondisseminating solitary plasmacytoma to actually represent a benign plasmacytic focus (ie, plasma cell granuloma), rather than a malignant process. [1] Extramedullary plasmacytomas are very rare and occur most often in mucosal tissues of the upper respiratory tract; they have a better prognosis, with only one-third of patients progressing to full multiple myeloma. [9]

Solitary plasmacytomas present on radiographs as a septated or expansile lesion, or a combination of the two, instead of the purely lytic “punched-out” lesions that characterize the multiple form of the disease. [1] An involved vertebral body may collapse and disappear completely, and in rare cases the lesion may invade across the intervertebral disc and affect an adjacent vertebra. Radiographically, this may simulate the findings of osteomyelitis or chordoma. Clinical findings may include backache, radiculitis, or even paraplegia caused by spinal cord compression. [1] Because of the expansive nature of plasmacytomas, they are more likely to cause spinal cord complications than is multiple myeloma. [4]

For the imaging of the patient in this report, addition of contrast to the magnetic resonance images was not necessary to arrive at a diagnosis, but it should be considered when ordering a magnetic resonance imaging to rule out malignancy. Other imaging modalities such as scintigraphy or positron emission tomography are very sensitive for finding subtle foci of disease involvement because they excel at detecting marrow replacement by plasma cells. [10] These advanced imaging modalities may be desirable to detect those patients who are in the midst of progressing from plasmacytoma to multiple myeloma and may not have radiographically visible lesions. [11]

Table 1 Table 1 shows a summary of the nonmechanical causes of neck and back pain. The table is not all inclusive but includes some of the organic disease processes that may present similarly to nonspecific neck and back pain. It should prove beneficial in the clinical and diagnostic decision-making process when determining the possible causes of a patient’s symptoms.

Treatment of spinal plasmacytoma lesions will vary based on the degree of involvement of the vertebral body. A combination of radiation and surgical resection is the most common treatment. A pathologic compression fracture is found in up to 60% of myeloma patients, [12] and if enough of the vertebral body remains intact, a vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty procedure may be implemented to help restore structural integrity and reduce residual deformity. [13] Advances are continually being made in minimizing the invasiveness of spinal surgeries, which is to be desired because conventional open surgeries are associated with increased blood loss, higher incidence of infection, and longer duration of surgery. [14]

Limitations

This is a case report; thus, findings of this study may not necessarily apply to other patients or clinical situations.

Conclusion

This case suggests that all practitioners of manual medicine provide a careful analysis of the patient’s clinical presentation and, if clinically warranted, radiographic examination to determine if neck or back pain is due to an underlying malignant condition. A cursory examination of this patient may not have revealed the more serious cause of his neck pain.

Practical Applications

A patient presented to a chiropractic office with neck pain, and after radiographic

examination, a plasmacytoma was discovered.This case suggests that a careful analysis of the clinical presentation and

appropriate radiographic examination may help to determine if neck pain

is due to a malignant condition.Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): R.P., W.M.C., C.D.W., D.R.P.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): R.P., W.M.C., C.D.W., D.R.P.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): R.P., W.M.C., C.D.W., D.R.P.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): R.P., W.M.C., C.D.W., D.R.P.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): R.P., W.M.C., C.D.W., D.R.P.

Literature search (performed the literature search): R.P., W.M.C., C.D.W., D.R.P.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): R.P., W.M.C., C.D.W., D.R.P.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): R.P., W.M.C., C.D.W., D.R.P.References

Resnick D. 4th ed.

Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2002.

Diagnosis of Bone and Joint Disorders.

[1040, 2203-2204, 2258-2259, 2303-2304, 3786-3796, 4274-4351]Juhl J, Crummy A, Kuhlman J. 7th ed.

Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia, PA: 1998.

Paul and Juhl’s Essentials of Radiologic Imaging; pp. 158–159.Guo SQ, Zhang L, Wang YF.

Prognostic factors associated with solitary plasmacytoma.

BMC Cancer. 2006;6:1659–1666Baba H, Maezawa Y, Furusawa N.

Solitary plasmacytoma of the spine associated with neurological complications.

Spinal Cord. 1998;36(7):470–475Loftus C, Michelsen CB, Rapoport F, Antunes JL.

Management of plasmacytomas of the spine.

Neurosurgery. 1983;13(1):30–36Gossios K, Argyropoulou M, Stefanaki S, Fotopoulos A, Chrisovitsinos J.

Solitary plasmacytoma of the spine in an adolescent: a case report.

Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32(5):366–369Voulgaris S, Partheni M, Gousias K, Polyzoidis K, Konstantinou D.

Solitary plasmacytoma of the upper cervical spine: therapeutic considerations.

J Neurosurg Sci. 2008;52(2):55–59von der Hoeh NH, Tschoeke SK, Gulow J, Voelker A, Siebolts U, Heyde CE.

Total spondylectomy for solitary bone plasmacytoma of the lumbar spine in a young woman.

Eur Spine J. 2014;23(1):40–42Arnesen M, Manivel J.

Plasmacytoma of the thoracic spine with intracellular amyloid and massive extracellular

amyloid deposition.

Ultrastruct Pathol. 1993;17:447–453Regelink JCL, Minnema MC, Terpos E.

Comparison of modern and conventional imaging techniques in establishing multiple

myeloma-related bone disease: a systematic review.

Br J Haematol. 2013;162(1):50–61Warsame RL, Gertz MA, Lacy MQ.

Trends and outcomes of modern staging of solitary plasmacytoma of bone.

Am J Hematol. 2012;87(7):647–651Mulligan M, Chirindel A, Karchevsky M.

Characterizing and predicting pathologic spine fractures in myeloma patients with

FDG PET/CT and MR imaging.

Cancer Investig. 2011;29(5):370–376Mendoza S, Urrutia J, Fuentes D.

Surgical treatment of solitary plasmocytoma [sic] of the spine: case series.

Iowa Orthop J. 2004;24:86–94Venkatesh R, Tandon V, Patel N, Chhabra HS.

Solitary plasmacytoma of L3 vertebral body treated by minimal access surgery:

common problem different solution!

J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6(4):259–264

Return to CASE STUDIES

Since 12–07–2017

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |